Author: Anna Torbecke, May, 2025

1 Introduction

Human behavior is a major contributor to environmental problems.1 One of these environmental issues is the increasing concentration of greenhouse gases in the Earth’s atmosphere, which is affecting the climate and causing visible changes such as forest fires and droughts around the world.2 As a result, the environment is a concern for today’s society, with 78% of citizens in the European Union (EU) agreeing that environmental issues have a direct impact on their daily lives and health.3 In addition, 38% of the EU citizens feel particularly vulnerable to extreme weather events, including droughts.4 Consequently, sustainability is a growing concern in the modern society as it seeks to deal effectively with environmental problems and resulting conflicts.2,5 Therefore, companies are inevitably incorporating sustainability into their agenda as well.6

Sustainability integrates social, environmental, and economic dimensions.7 The challenges of sustainability within these dimensions cannot be met without long-term changes in individual behavior.8,9 Thus, increasing the sustainable behavior of individuals is crucial.10 In particular, sustainable consumption behavior, which aims to address environmental issues and reduce the environmental impact of consumption, gained increasing interest in recent years and is influenced by values as an internal motivator and social norms as an external factor.7 Therefore, the substantial impact of human behavior, with social norms and values as important antecedents, on environmental problems and the variation in efforts to behave in a pro-environmental manner is a concern that must be addressed.11 Incorporating sustainability within firms requires creating long-term value by adopting a business approach that balances the three dimensions of sustainability equally.6 In this context, the corporate culture, including social norms and values, has a significant impact on the behavior of companies and managers and, hence, also shapes the adoption of sustainability.6

In the context of sustainable behavior, psychological and sociopsychological factors are highly relevant.12,13Psychological factors include values, which influence individuals’ decisions by exerting internal motivation.7 Values are typically deeply rooted in individuals’ personalities and provide a fundamental basis for behavior.14 They exert a stronger influence on individual behavior than external forces and have emerged as a focal point in environmental research.15,16 Thus, individual and collective decisions are influenced by values: As values shift toward sustainability, the subsequent decisions are more protective of the environment.17 When it comes to environmental issues, changing values is one way to achieve sustainable behavior.17 Personal values are closely related to personal and social norms.18

Sociopsychological factors include social norms and represent primarily external factors influencing behavior when not internalized by the individual.7,12,19 Social norms are attracting the attention of scholars in a variety of fields because they are influencing a wide range of behaviors.20 Humans are social individuals, so among other factors, their behavior is influenced by social norms.2 Individuals engage with and through social norms with each other, using feelings of approval and guilt.21 In the context of environmental issues, individuals have limited control over public policy and their individual actions have no impact on the large-scale structural problem of climate change, thereby social norms can play a critical role in reinforcing and amplifying behavior.21 Furthermore, shifts in social norms and changes in behavior can be required, as unsustainable norms pose a challenge when attempting to create appropriate individual behavior on environmental issues.22,23 In this regard, social norm interventions can be effective to achieve behavior change or encourage individuals to adopt a behavior by emphasizing the prevalence of existing sustainable norms.2,20

Social norms differ from values in that they include the aspect of conforming to the normative expectations of others.24Although they are separate concepts, both are intertwined and relevant to sustainable choices of individuals and groups.7 Both influence behavior through values, which influence internalized norms, and perceived social norms, which influence compliance.25 However, the value placed on sustainability does not translate into practice in every context, depends on cultural differences, and thus remains a concern.6 For example, social norms, rather than supporting sustainable behavior, can also increase unsustainable behavior among individuals such as frequently flying or driving alone.2,23 The substantial influence of social norms and values on behavior at the individual and corporate levels provides the motivation and need for the academic study of the two concepts in relation to sustainability.

Hence, this thesis aims to provide a structured overview of the current state of research on the concepts of social norms and values in relation to sustainability, and to translate this research into practice to promote the transformation towards sustainability. To provide a comprehensive examination of both concepts in relation to sustainability, various aspects are analyzed separately. Despite the rich body of research in both areas and their high practical relevance, conceptual vagueness and lack of clarity persist.7,13,20 Both concepts lack universally accepted definitions as they are studied by diverse disciplines.2,17 Moreover, the lack of clarity also stems from the fact that there is no universally accepted measure for either concept, making it difficult to compare the results across studies.2,26 Furthermore, the influence of social norms and values on behavior is often underestimated by individuals themselves and by the research community.20,27 This is particularly critical in the context of sustainability, as social norms and values can significantly impact behavior.20 Also, the relationship between social norms and values is complex.11 For instance, in some contexts and situations, the expression of values can be considered less important and individuals may rely stronger on external norms when making behavioral decisions.11 These considerations highlight the relevance of giving a structured overview of the current state of research on social norms and values for both academia and practice. A deeper understanding provided by this work contributes to the development of targeted measures and strategies to promote sustainable behavior on a broader scale.

The structure of this thesis consists of methodology, literature review, practical implementation, and conclusion: First, the methodology – a literature review – is presented. Then, the key terminology and historical background of both fundamental concepts are explored. With the focus on social norms in the context of sustainability, measurement methods and drivers are explored, followed by an analysis of the behavioral outcomes and the moderators of the behavioral outcomes. Subsequently, the focus shifts to values, following the same structure as for social norms. The investigation concludes with a summary of the key findings, and the identification of future research areas.

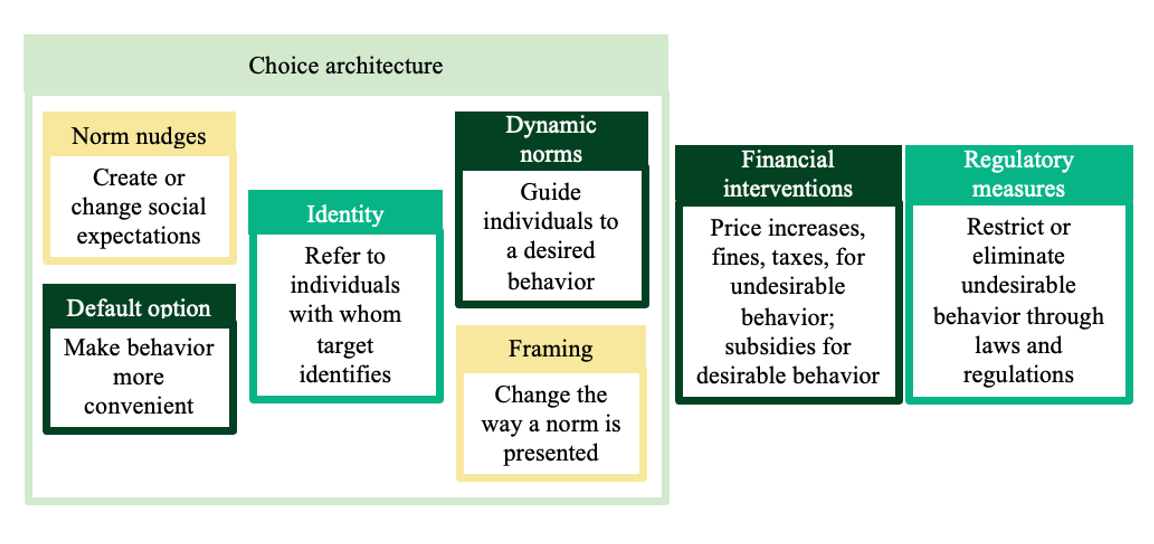

The practical implementation part begins with an exploration of effective approaches to promoting behavioral change toward sustainability. First, it provides insights into the design of interventions and policy strategies. It then examines alternative mechanisms for fostering behavioral change, while also considering relevant actors. Five best-practice examples provide information and frameworks on how the approaches can be applied in practice. To offer a comprehensive perspective, both internal and external drivers and barriers of the approaches are analyzed. The conclusion summarizes the key findings of both parts.

2 Literature Review of Social Norms and Values

The aim of this chapter is to provide an overview of the current research on social norms and values related to sustainability. First, the key terminology in social norms and values related to sustainability and the historical context are examined. This is followed by a review of key research areas in social norms that encompass the measurement, emergence, and diffusion of sustainable social norms, their behavioral influence on sustainable decision making, their role in collective action, and moderators of the relationship between social norms and sustainability. The central research domains of values in relation to sustainability are then reviewed, consisting of fundamental theories leading to measurement methods, the formation of sustainable values, the behavioral impact of sustainable values on sustainable actions and altruism, and moderators influencing the strength of the relationship between values and sustainability. To incorporate the central research areas of both social norms and values, the literature review focuses on the measures, drivers, outcomes and moderators of sustainability for both concepts. Finally, a summary of the current research insights is provided, and future research needs identified in the literature are explored.

2.1 Key Terminology

It is important to establish a unified understanding of the core concepts of social norms and values in relation to sustainability. In literature, there are no universal definitions for the concepts.2,17 Therefore, this chapter focuses first on the terminology of social norms before providing insight into the concept of values.

The definition of social norms varies considerably across the literature.2 According to Legros and Cislaghi (2020), authors agree that social norms are social and shared by some members of a group, relate to behaviors and inform decision making, and are capable of affecting the health and well-being of groups.31 For this thesis, the concept of social norms is defined as prevailing informational rules and standards understood and shared by all group members, shaped by expectations about what others in a relevant reference group do or think one should do, that guide interdependent patterns of behavior and expectations through the application of external forces.2,20,31-33 A reference group consists of relevant other individuals whose behavior, approval, or disapproval is important in maintaining the norm.31 Different social norms are tied to distinct reference groups.31 Social norms are considered self-enforcing, leading individuals to act in accordance with their beliefs about what others do or approve of doing, and they are also enforced by rewards for those who follow and sanctions for those who do not.2,22 Social norms can be viewed as the “[…] foundation of culture, of language, of social interaction, […]”34 (p. 147) and various other mechanisms.34 Unlike laws and regulations, social norms are inherently implicit, but as an element of culture, they can be formalized into laws when society chooses to institutionalize these cultural elements.6,20

Descriptive norms are understood as: “Behaviors that are commonly performed in a population and that are conditional on the empirical expectations about other people’s behaviors of beliefs”2 (p. 52), but they may differ from the actual behavior of individuals.2,20 Injunctive norms are understood as: “Common rules of behavior about what should be done in a population that are conditional on normative expectations about others’ beliefs of what should be done”2 (p. 52), reflecting how most people believe one should behave.2,20 A distinction can be made between personal injunctive norms, which describe what one approves of doing and are referred to as personal norms, and non-personal injunctive norms, which are consistent with injunctive norms.20 Personal norms refer to self-imposed rules regulated through internal sanctions or rewards, such as feelings of guilt or pleasure, that are followed regardless of external social approval and reflect an individual’s self-expectations.22,35,36 Personal norms can be internalized to the extent that they are partially or fully integrated into the individual’s self-concept and, therefore, do not require enforcement through guilt or pleasure.19 To distinguish between these two forms of personal norms, the terms introjected and integrated personal norms are used, with the former representing personal norms that are enforced through anticipated guilt or pride, and the latter representing personal norms that do not require enforcement through guilt or pride, but rather reflect on how the norm and the outcomes of compliance relate to one’s own values and goals.19 In addition to these categories, dynamic or trending norms have recently been added as a category that influences and guides the behavior of a population by highlighting a change in society.32

The difference between actual and perceived social norms refers to a verified norm about widespread regularities in a group’s beliefs or behaviors and a norm that is unverified but believed to be an actual descriptive or injunctive norm.20,35 Normative expectations of injunctive norms are perceived injunctive norms, and empirical expectations of descriptive norms are perceived descriptive norms, both of which may differ from the actual frequency of others’ behavior.2 A subjective norm refers to subjective assumptions, perceptions, or expectations about a social norm.35Subjective perceptions are derived not from surveys but from unique and local experiences, and therefore, the resulting perceptions rarely match actual rates of behavior.37

Values are the second concept that needs to be explained for the purpose of this thesis. A broader explanation divides values into three different understandings, seeing them either 1) as a thing’s worth or usefulness, or 2) as opinions about the worth or value of a thing or person, or 3) as moral principles, either individually or socially shared, reflecting generally accepted or personally held judgments about what is valuable in life.17,38 In the social sciences, values are defined as “[…] (a) concepts or beliefs, (b) about desirable end states or behaviors, (c) that transcend specific situations, (d) guide selection or evaluation of behavior and events, and (e) are ordered by relative importance”39 (p. 551), and in economics, values are more general ideas of the kinds of situations desired by individuals, are used to assess what society as a whole finds important, to guide collective decision making, and to provide a basis for resolving conflicts when preferences as specific evaluations of possible outcomes of a decision are in disagreement.17 According to Schwartz (2003), values are beliefs, refer to desirable goals, transcend specific situations and contexts, serve as standards, are ordered by importance, and guide actions by the relative importance of the set of relevant values.40Values are considered to be relatively stable over time.17 They are an integral part of human identities and reflect what individuals consider important and desirable.41 In addition, they are an important factor of culture, where each culture is thought to have its own value system.42 The importance attached to specific values can differ between groups.40

A distinction can be made between transcendental and contextual, social, economic, and environmental, and intrinsic and instrumental values. Transcendental values refer to broad conceptions of what is important in one’s life, representing overarching life goals and principles that guide contextual values.43 Contextual values are attached to a context-specific object of value, representing specific opinions about its importance.43 Social values are concerned with the individual and collective well-being of people, and are therefore altruistic and other-oriented.44 Economic values tend to be rather self-oriented, focusing on individual benefit, whereas environmental values emphasize the preservation of the earth’s natural systems that are essential for sustaining life.44 The debate over whether the environment and non-human species possess intrinsic value or instrumental value, meaning that they are considered valuable solely because they serve human purposes, is a key feature of environmental ethics.17

2.2 Historical Background

Because social norms and values exist in different contexts, they have been studied in a wide range of literature, both with and without a focus on sustainability. There are different definitions, understandings, and theories of social norms and values in, for instance, psychology, economics, and sociology.17,45 Economics studies social norms in terms of objective patterns of behavior within a social context, while psychology equates norms with subjective constructs rooted in beliefs and perceptions.35 Syed and colleagues (2024) provide a comprehensive overview of theories and models that should be taken into consideration when examining sustainable consumption behavior.7 In order to explore the relationship of the concepts to sustainability and to establish a foundation for examining the central research areas, a relevant subset of theories arising from the introduction of the concepts and influencing their historical development as well as current research streams must be briefly examined. For the purpose of this thesis, an examination of relevant theories is more appropriate than a detailed look at the historical development of the concepts.

The first relevant theory is the Norm Activation Theory of altruism (1977) by Schwartz, which is concerned with behavior aimed at helping others beyond an individual’s own self-interest.36 Thus, it refers to the circumstances under which social norms give rise to altruistic behavior.17,36 It posits that pro-environmental behavior arises from personal norms activated when individuals perceive environmental conditions as a threat to other people, species, or the biosphere, referred to as awareness of consequences (AC), and believe that their actions can mitigate the consequences, referred to as ascription of responsibility (AR) to the self.46 The theory forms the foundation for the Value-Belief-Norm (VBN) theory explained below.17 It has been successfully applied to pro-environmental behavior.46 Schwartz introduced the Norm Activation Model (NAM) (1977) to further understand how internalized (personal) norms influence pro-social behavior.25,36 It states that, an individual will behave according to a norm when the norm is acknowledged, and the conditions of AC and AR beliefs are met.25,47

Directly related to the environment is the New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) (1978) by Dunlap and colleagues.48 It states that the emergence of the environmental movement is closely associated with the increasing adoption of a new ecological paradigm or worldview.46,48 Thus, it recognizes that human actions have significant negative impacts on the fragile balance of the biosphere.46,48

Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (1985) states that an individual’s intention, together with perceived behavioral control, serves as a motivational factor that influences the likelihood of performing a behavior.49 The theory examines three factors that influence the intention to engage in a behavior: 1) perceived behavioral control, which refers to an individual’s perception of their ability to perform the behavior, reflecting past experiences, obstacles, and anticipated difficulties, 2) attitudes toward the behavior, which refer to the degree of positive or negative evaluation or appraisal of performing the behavior, and 3) subjective norms, which refer to the perceived social pressure to perform or refrain from performing a behavior.49 The greater the three key factors, the stronger the individual’s intention to perform the behavior, although the importance of the factors varies by behavior and context.49 In addition, perceived behavioral control, combined with behavioral intention, can serve as a direct predictor of behavioral performance.49

The Focus Theory of Normative Conduct (1990) by Cialdini and colleagues distinguishes between two types of norms that differ in their influence on behavior: descriptive and injunctive norms.50 It states that norms only directly influence behavior when they are focal in attention and salient in consciousness during the decision-making process.50The salience of norms is examined in the Model of Social Norm Activation (2006), which states that norm activation requires three conditions: the beliefs that the norm exists and is relevant to the situation, that a significant proportion of people in similar situations comply with the norm, and that a sufficiently large subset of individuals in similar situations expects conformance to the norm.24,51 It is useful in business ethics research.51

Setting the focus on values, Schwartz’s Theory of Basic Human Values (1992) identifies ten basic values characterized by different motivational goals: power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation, self-direction, universalism, benevolence, tradition, conformity, and security.17,40 These values are arranged along two dimensions: One dimension contrasts self-enhancement, which refers to an individual’s self-interest and personal goals, with self-transcendence, which emphasizes the concern for the welfare and interests of others.17,40 The second dimension contrasts openness to change, which highlights the readiness for change, interdependence and freedom, with conservation or traditionalism, which emphasizes self-restraint, preservation of traditional practices, and maintenance of stability.40 The ten values are interrelated, forming a dynamic and interdependent circular structure in which adjacent values are compatible, while opposing values pursue conflicting goals and are less likely to be activated simultaneously.52 Individuals may weigh the importance of the ten basic values differently, but the values remain structured within the same framework of motivational oppositions and compatibilities.40

Stern and Dietz’s Value-Basis Theory (1994) extends the work of Schwartz to environmental attitudes and behaviors.10,53 They establish three bases for environmental concern: 1) egoistic values, which capture individuals who protect aspects of the environment that personally affect them and resist protection when personal costs are assumed to be high, 2) social-altruistic values, which refer to the concern extended from the individual and their family to the broader community, and 3) biospheric values, which focus on the well-being of other species or the health of ecosystems, beyond their benefits to humans, also understood as intrinsic value.17,53 Individuals form their behavioral attitudes based on their anticipation of how objects, such as environmental conditions, will affect specific groups.10,53Values emerge as the key determinants that influence expectations and play a critical role in influencing environmentally protective behaviors.10

The VBN theory (1999) by Stern and colleagues examines how individual values, beliefs, and norms influence support for environmental movements taking into account Schwartz’s model of human values and the NEP.46,54 According to the theory, people support environmental movements when they perceive environmental threats, believe that their actions can reduce the threats, and feel a moral obligation to act in the form of personal norms.46 Thus, a causal chain is assumed in which values shape environmental beliefs into more focused beliefs about human-environment relationships, referring to the NEP, which influence AC and AR beliefs, and finally activate personal norms that lead to pro-movement actions; the process can be summarized as follows: “[…] values (especially altruistic values), NEP, AC beliefs (not measured in this study), AR beliefs, and personal norms for proenvironmental action”46 (p. 85).46 In addition, context shapes the type of support.46

2.3 Central Research Areas on Social Norms

The concept of social norms in relation to sustainability has several central research areas. They are examined in the following four chapters and include: the measures, emergence, and diffusion of sustainable social norms, the behavioral influence of sustainable social norms in decision making, the role of sustainable social norms in collective action and organizational adoption of sustainability, and moderators influencing the relationship between social norms and sustainability. Next, this chapter gives a more detailed overview of social norms by providing different constructs. Then, this chapter gives a comprehensive overview of the central research areas by focusing on measures, drivers, outcomes, and moderators of sustainable social norms.

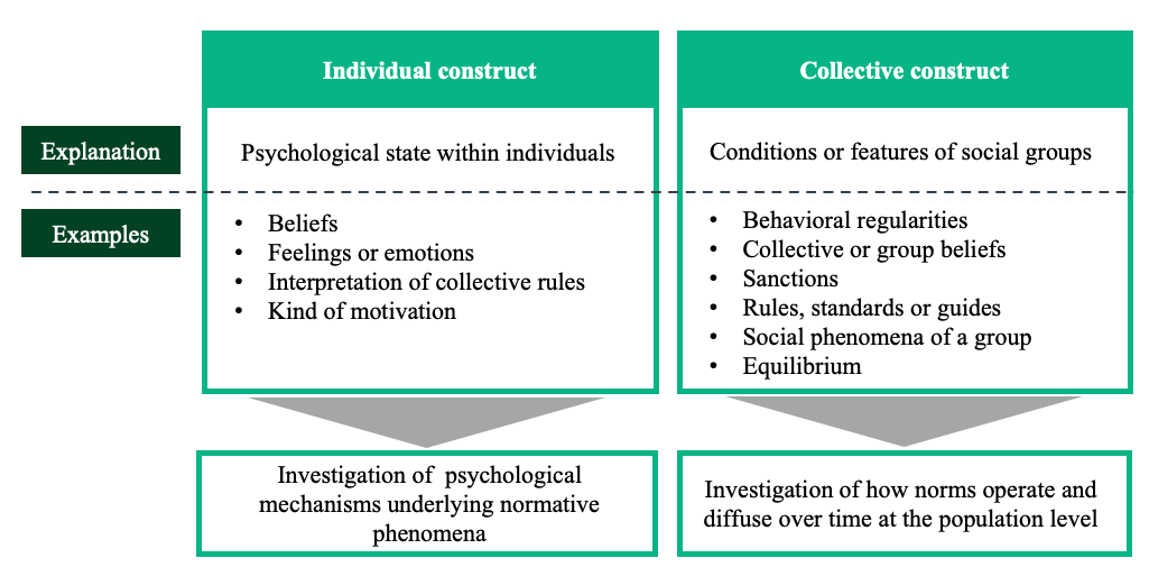

Regarding the constructs of social norms, Legros and Cislaghi (2020) identify two primary constructs shown in Figure 1: the individual construct, which views social norms as a psychological state within individuals, such as beliefs, feelings or emotions, the interpretation of collective rules, or a type of motivation; and the collective construct, which views social norms as conditions or features of social groups, such as behavioral regularities, collective or group beliefs, sanctions, rules, standards or guides, a social phenomenon of a group, or an equilibrium.31 Various reviews in the social norms literature either consider the constructs independently or attempt to integrate the two: The individual construct is useful for studying the psychological mechanisms underlying normative phenomena, while the collective construct is helpful for investigating how norms operate and diffuse over time at the population level.31 Cross-disciplinary work should incorporate both constructs, as will be strived to in this thesis.31

Figure 1: Constructs of Social Norms, Own illustration, based on Legros and Cislaghi (2020).31

2.3.1 Measures

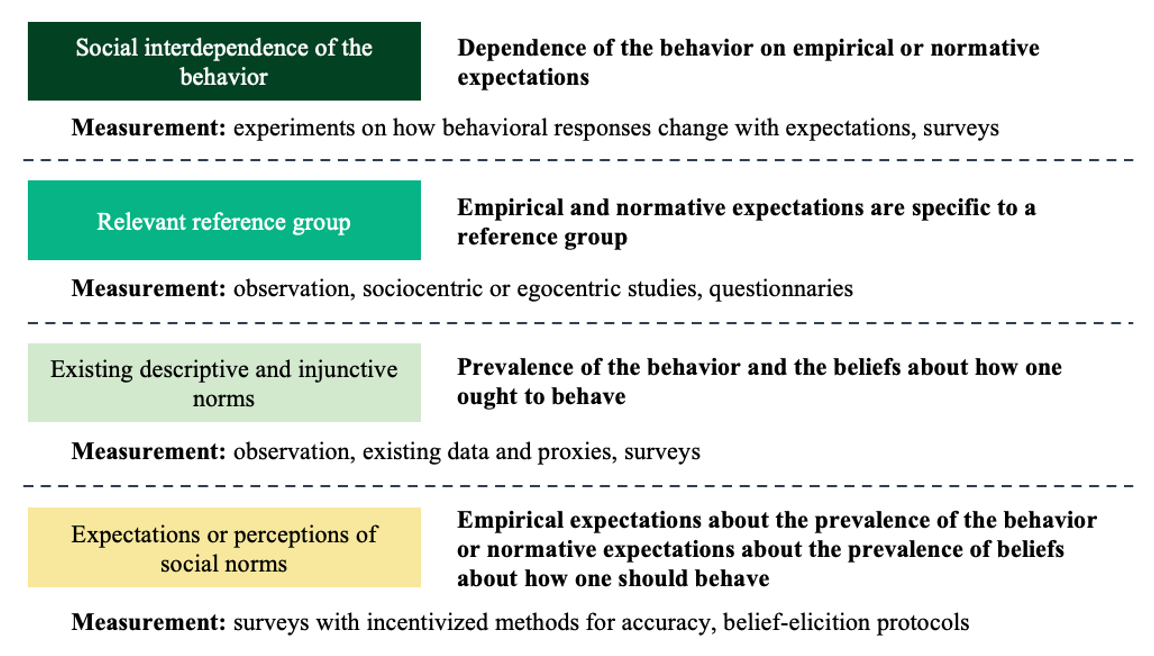

Constantino and colleagues (2022) synthesize the literature on social norm influence and measurement, focusing on social norms for climate action that correspond to sustainable social norms.2 They identify key methodological steps that guide the identification and measurement of a sustainable norm.2 In this thesis, the steps are examined by first identifying the social interdependence of the behavior and the relevant reference group, then measuring existing descriptive and injunctive norms, and finally measuring expectations or perceptions of social norms.2 The steps are visualized in Figure 2. Each of these steps can be addressed through a variety of means, including surveys, questionnaires, observations, and experiments.2

Figure 2: Measurement of Sustainable Social Norms, Own illustration, based on Constantino and colleagues (2022).2

When measuring sustainable social norms, it is necessary to determine whether the behavior represents a social norm by being socially interdependent.2 To assess social interdependence, empirical or normative expectations are measured to determine whether the motivation to engage in a behavior depends on an individual’s belief about what is typically done or should be done.2 Thus, it is necessary to determine whether the expectations have a causal influence on behavior.55 The social interdependence of a behavior can be measured through surveys or experiments: Experiments allow to manipulate empirical or normative expectations and examine whether and in what ways the behavior changes with the expectations.2,55 For instance, studying participants’ behavior with and without the influence of a descriptive or injunctive social norm intervention allows to investigate whether the behavior changes as a result of the norm intervention.2 If the behavior changes depending on the empirical or normative expectations, it is socially interdependent and indicative of a social norm, if no change occurs, the behavior does not qualify as a social norm.2

In addition to examining social interdependence, it is essential to identify the context- and behavior-specific reference groups, since empirical and normative expectations are inherently tied to a specific reference group that is salient for the behavior.2 Since social norms and sustainable norms tend to vary by group, they must be measured separately for each reference group.2 In some cases, the reference group is easily observable, in other cases research is required.2 This can be done through questionnaires, sociocentric studies that map connections by surveying all members of a network, or egocentric studies that collect information on individual’s social ties by focusing on a sample of individuals within the population.2,56-58

In the case of measuring existing descriptive norms, some behaviors are easily observable, or captured by existing data, such as the number of solar panels in a community.2 However, less observable behaviors need to be measured though proxies, which may include surveys or focus group discussions.2 These allow researchers to observe interactions and participants’ reactions, helping to identify variations in the presence and strength of sustainable social norms.2Injunctive norms cannot be measured by observation because they involve personal normative beliefs or expectations about whether the behavior should be performed or is endorsed.2 To measure injunctive norms, these personal normative beliefs must be elicited through surveys that ask individuals about the prevalence of the belief that one should engage in the behavior.2

Perceptions of descriptive norms cannot be observed, and must be measured through surveys that explore individuals’empirical expectations about the behavior of others.2 They are based on unique and local experiences of individuals.37Depending on the topic, individuals may not be sufficiently motivated to answer questions accurately, but can be incentivized through rewards.2,59 One way to assess expectations is to begin by assessing personal normative beliefs in a sample of the population with using a bonus payment based on the degree of alignment between participants’responses and normative beliefs previously gathered in the study.2 Another approach to measurement is through belief-elicitation protocols, which can be useful to measure expectations regarding the prevalence of behavior.2 Both approaches can be used to determine whether the majority believes there is a prevailing norm in a given situation, to compare the actual behavior and empirical expectations, and to investigate whether the perceptions are accurate.60Perceived injunctive norms are measured using surveys to assess how common it is to believe that others think one should perform the behavior, which can also be incentivized with rewards for accuracy.2,60

Since personal norms are strongly related to the concept of social norms, Dalvi-Esfahani, Ramayah, and Rahman (2017) propose a measurement method in which participants are provided with different statements and answer to what extent they agree or disagree with these statements using a five-point Likert scale.61

2.3.2 Drivers

Research on social norms has identified various mechanisms and stages involved in their emergence, learning, and diffusion in society. According to Legros and Cislaghi (2020), the emergence stage in the life cycle of a norm consists of various substages, as shown in Figure 3.31 This thesis focuses on three key processes: norm creation, norm learning, and norm diffusion. To provide a comprehensive overview, the learning stage is divided into pre-learning, reinforcement learning, and internalization stages, according to Zhang and colleagues (2023).62 Although, according to Schneider and van der Linden (2023), there is not enough research to examine the longevity of social norms or the extent to which individuals internalize social norms, this chapter provides valuable insights into the creation, learning, and diffusion of social norms as they overlap with sustainable social norms.32 Understanding these processes provides valuable insights into the drivers of sustainable social norms.

Figure 3: Stages in the Emergence of a Norm, Own illustration, based on Legros and Cislaghi (2020).31

Theories of norm creation differ in the specific ways in which social norms emerge.31 They suggest that either behavior change precedes norm change, norm change drives behavior, or the two influence each other mutually, which means as a behavior becomes more regular in a population individuals come to perceive it as a norm, which reinforces compliance.31 When behavior change precedes norm change, changing the prevalence of a behavior and repeated interactions in smaller homogeneous groups lead individuals to adopt behaviors that eventually shape norms.22,35Conversely, when norm change drives behavior, new behaviors can arise from changes in group norms, which can occur relative abruptly.63 Finally, the mutual influence is evident in social activism and movements where social norms emerge, spread, and effect policy change.2 One feature of social norm emergence is its unpredictability: Communities with similar socioeconomic characteristics exposed to the same influences may develop different norms if they do not interact with each other.45 Additionally, the constantly changing and dynamic environments in which people live, can lead to norm change or the emergence of sustainable social norms.64

Zhang and colleagues (2023) study the learning of social norms and introduce an integrated model of social norm learning that consists of a pre-learning stage focused on gathering information or cues during interaction, a reinforcement learning stage focused on social feedback and making adjustments, and a norm internalization stage.62Regarding the first stage, individuals need to gather normative information by paying attention to cues from situational sources such as the place, the event, or the group and social sources, such as education or signs.62 According to Tankard and Paluck (2016), this can be achieved through three main sources: observing the behavior of others, receiving information about a group, and the signals sent by institutions.37

Regarding the first source, the actions of others provide important information about what is considered good and effective in a social group.23 Both descriptive and injunctive norms are socially interdependent behaviors and, in some contexts, can be transmitted by observing the behavior of close social networks such as family, friends, or partners.2,65Specific individuals, known as “social referents”, have a stronger influence on norm perception, because their behavior is more salient, due to their personal connection to the perceiver and the number of connections in the group.37Learning social norms through observation requires social cognition, including the ability to share and understand others’ mental states and behaviors.31,62 With regard to the second source, perceptions of norms are shaped by information about a reference group, which can be provided by sources such as social media statistics, marketing, or warning signs.37 Finally, institutions such as governments or schools can signal desirable behaviors and provide information.37 Policies incentivizing or regulating behavior, changes in the physical environment, or educational campaigns can lead to the uptake of social norms by providing information.2 In addition, legal reforms can sometimes shift society’s beliefs about what is approved.31 However, since individuals select the sources of normative information, the resulting perceptions of norms often diverge from the actual prevalence of the behavior.37

After gathering information in the pre-learning stage, the three interacting components of the reinforcement learning stage are assessed, consisting of social norm prediction, social feedback, and adjustment; for the purpose of this work, context-based-processing is added as an additional component of the learning process.62 The first stage consists of forming the initial representation of the social norm using the information gathered in the pre-learning stage.62 The second stage of social feedback during interactions, such as emotional and physical actions, provides learners with cues about appropriate behavior, where the type of the social feedback is shaped by cultural influences.62 Individuals imitate others and receive direct corrections from peers that guide the expected behavior, leading to the learning of social norms.62,66 In addition, individuals can observe social feedback on the behavior of others.62 Consequently, cooperation is essential in the learning of social norms.35 However, the adoption of a new norm may require multiple sources of social reinforcement to be established.2 Finally, after receiving social feedback, individuals adjust and update their perceptions of the social norm.62 However, a high prediction error may lead to cognitive conflicts among individuals regarding their predictions and hinder the acquisition of new social norms.62 Context-based processing is required because the recognition of social norms in interaction during the learning process depends on the specific circumstances and social contexts.62 Social norms are contingent on the context, the social group, and historical equilibria, resulting in multiple potential norms in a society, further emphasizing the need for context-based processing.45 For instance, moving to a new city may exert cultural differences and require individuals to learn social norms in a new culture and context to respond to norm changes and accelerate faster.62

The internalization of norms, as the final stage of learning norms, results in individuals conforming to the internalized norm even when others around them do not.62 Norms can be internalized as values, as a representation of the prevalence of a behavior among others, or as a default option when exposed to uncertain situations.62,67 They can serve as markers of a group, play a role in distinguishing ingroup members, and promote cooperation within the group.35Internalization is considered to be a slow process that requires intensive, sustained socialization experiences.35 To distinguish the degree to which norms have been internalized, Thøgersen’s extended taxonomy of social norms is used, where the least internalized norms are considered to be external descriptive norms, followed by subjective injunctive norms, introjected norms, and integrated norms: The last two are categorized as personal norms.19 Thus, personal norms are internalized social norms.19 However, personal norms are also influenced by individual values.68

The diffusion of social norms through various social networks, which refer to the web of interpersonal connections within a society, is concerned with tipping points.2 Social tipping refers to the process by which a critical mass of people adopt a new behavior, leading to the spread of the norm change through social networks.63 Norms can spread between groups and eventually influence the behavior of groups on a large scale.63 The process is accelerated when the behavior is easily observable and social sanctioning increases the number of followers, creating tipping points where the social sanctioning of violators increases further, spreading the social norm to a new group.63 Thus, practices that others discover to have value spread through the tendency for imitation and coordination.35 However, when the behavior is difficult to observe, tipping points are unlikely to be reached.63

2.3.3 Outcomes

Once emerged, learned, and diffused, social norms influence a wide range of environmental behaviors, especially in contexts where limited knowledge or concerns about acting alone can impede actions.23 Thus, social norms represent a powerful driver of behavior, with sustainable social norms associated with increased sustainable behavior.15,68,69However, many unsustainable behaviors are the norm, such as flying or driving alone, implying that these behaviors are effective in achieving goals, and individuals may be judged negatively if they do not comply.23 This chapter first explores the cognitive and motivational processes that drive adherence to sustainable social norms at both the individual and the collective levels. It then examines the business context with respect to the influence of sustainable social norms on sustainability adoption and the role of leaders.

The literature generally agrees that social norms influence behavior primarily through the implications of expected material and psychological payoffs, with context shaping the impact of norms on decision making.20 Individuals comply with social norms when they expect others to do the same, but the precise mechanisms or motivations that create a positive feedback loop vary across contexts.45 Table 1 provides an overview of theories, selected processes, and motivations that influence compliance with social norms. While a comprehensive discussion of theories and mechanisms is beyond the scope of this thesis, key aspects relevant to the relationship between social norms and sustainable behavior are analyzed in more detail.

Table 1: Theories, Processes, and Motivators of Norm Compliance, Own illustration.

| Author(s) | Variables of Compliance |

| Legros and Cislaghi (2020) | Norms influence behavior by offering value-neutral information and by generating external or internal obligations.31 |

| Sugden (2000) | Individuals comply with norms to avoid resentment from others and to maximize their payoffs while reducing the behavior’s negative impact on others’ payoffs (Theory of Normative Expectations).70 |

| Constantino and colleagues (2022) | Individuals conform to social norms to maintain social relationships, to achieve mutual benefits in coordination, and because of behavioral constraints.2 |

| Nyborg, Howarth, and Brekke (2006) | Individuals’ consumption behaviors in environmental decisions are driven by self-image concerns, which are influenced by individuals’ beliefs about positive external effects and perceived responsibility to behave prosocially based on descriptive norms.71 |

| Bicchieri (2006) | Conformity occurs when individuals hold a perceived descriptive norm and a perceived injunctive norm that are sufficient to convince them to conform.24 |

| Morris and colleagues (2015) | Internalization, social identity, rational choice, social autopilot, and social radar theory are variables of norm conformity.35 |

| Lapinski and Rimal (2005) | The ways of communication, injunctive norms, group identity, and ego involvement are factors that influence the relationship between descriptive norms and behavior.72 |

| Tajfel and Turner (1979) | The human desire to belong to a community drives compliance with social norms as a means of expressing group membership (Social Identity Theory).73 |

| Thøgersen (2006) | Two types of personal norms, integrated and introjected norms, predict sustainable behavior.19 |

| Sparkman and Walton (2017) | If static norms are undesirable, dynamic norms can lead people to behave in desirable ways.74 |

To explore the outcomes at the individual and the collective levels, Legros’ and Cislaghi’s (2020) distinction between norms conveying information, and being external, or internal obligations will be used in the following.31 Examining the dimension of social norms conveying information about shared behaviors considered as wise choices, social norms can regulate individuals’ behavior, provide guidelines for navigating social interactions, and align individuals with group expectations.2,35 In the context of sustainability, social norms can help individuals understanding how to take effective action against climate change, thereby functioning as reliable sources of motivation.23 Because social norms signal which behavior is an effective way to deal with climate change, individuals can learn from the norms without understanding the complex systems.23 Thus, individuals often draw on the actions of others to infer what constitutes appropriate behavior.2

Internal obligations refer to the internalization of sustainable social norms: Thøgersen’s theory suggests that both integrated and introjected norms predict sustainable behavior, and that the internalization and integration of sustainability motivation increase the adherence to sustainable norms.19,31 However, it also states that individuals can apply different norms for different sustainable behaviors.19 Nevertheless, internalized social norms serve as intrinsic motivators influencing an individual’s behavior.23,31 Before a norm becomes integrated, conformity depends on anticipated guilt or pride, but as it becomes integrated, the influence of observability and normative expectations on conformity decisions diminishes as individuals conform to express their values.19,35 Helferich, Thøgerson, and Bergquist (2023) analyzed the predictive strength of injunctive, descriptive, and personal norms and found that internalized (personal) norms are the most robust predictor of pro-environmental behavior.75 Moreover, personal norms mediate most of the effects of descriptive and injunctive norms, but both types of social norms do have an effect when controlling for personal norms.75 However, they were unable to differentiate by Thøgerson’s typology.75 Thus, personal norms may be more predictive of sustainable behavior than injunctive or descriptive social norms, which are important in an indirect way.19,75 In addition, individuals with strong personal norms tend to be less influenced by contrasting social norms.32 Silvi and Padilla (2021) emphasize that mostly internalized environmental norms influence pro-environmental behavior, but also external forces such as policies influence conformance.25

External obligations consist of, for instance, peer pressure, and the expectation of rewards or punishments such as social approval or disapproval.31 The Social Identity Theory emphasizes the desire to belong to a community as a key component of social norms driving behavior, suggesting that norm adherence expresses group membership.23,35,73Individuals categorize themselves and others into groups, shifting their thinking and identifying with the typical traits, behaviors, and attitudes of the group, rather than focusing on unique personal qualities.35,73 Group norms are flexible perceptions that can shift rapidly but form group identity.34,35 Therefore, behavior is supposed to be easily abandoned with a change in an individual’s self-categorization.35 Sparkman, Howe, and Walton (2020) confirm that individuals’ motivation to belong to social communities and conform to social norms is a basic social orientation that is essential for individuals’ sustainable behavior with respect to climate change.23 Thus, norm messages that promote sustainable behavior by referring to people with whom the individual identifies improve the outcomes.2,76 White and colleagues (2009) find strong evidence for group-specific norms that refer to social identity and weak support for perceived descriptive and personal norms influencing behavior, in contrast to the evidence for internal obligations mentioned above.77 Thus, social influence can encourage sustainable consumption when it helps to signal identity or group membership, even if it is associated with costs to the individual.78

External obligations can be linked to the observability of and by others, as the visibility of sustainable behavior is important for targeting the sustainable behavior of others in the context of social norms.5 In many cases, individuals conform to social norms that are not integrated only if specific conditions including the observability of behavior and the presence of normative expectations hold.20 For instance, Lapinski and Rimal (2005) find that social norms have little influence on behavior when it is not observable.72 If the behavior is visible, individuals may feel accountable and face greater risks by not complying.2 As a result, their behavior is more sustainable.2 On the other hand, Melnyk, Carrillat, and Melnyk (2022) find evidence that social norms have the same influence on private as on public behavior.69 In detail, the gender of the targets can affect the influence of observability on norm compliance.79 When examining food choices after communicating a social norm message, the visibility of choices particularly influences women to choose vegan or vegetarian alternatives, whereas men are more likely to choose meat regardless of whether they are observed and violate the norm.79 However, without a social norm message, visibility does not have a significant effect on food choices for either gender.79

Considering the impact of social norms on sustainable behavior, the difference in the influence of descriptive and injunctive norms must be accounted for which is outlined in the Focus Theory of Normative Conduct.50 Descriptive social norms motivate individuals to act through social information, while injunctive norms drive action through social evaluation.27 There is no consistent result as to whether injunctive or descriptive norms have a stronger influence on sustainable behavior: Some scholars examine that both descriptive and injunctive norms have a significant effect on pro-environmental behavior or no type of norm is more effective, which can also depend on the context.65,80 In contrast, other scholars suggest that descriptive norms in particular have an impact on pro-environmental behavior.20,69This perceived dominance of descriptive norms in influencing behavior can be due to the fact that researchers have focused more on descriptive than on injunctive norms, citing a need to study injunctive norms more intensively.81However, Rhodes, Shulman, and McClaran (2020) found that injunctive norms are more influential than descriptive norms.82 Still, the norm influence on behavior is stronger when both descriptive and injunctive norms are consistent.2In this regard, a country level pro-environmental norm influences pro-environmental behavior by positively influencing both injunctive and descriptive norms of relevant others.65 When only one norm is given, individuals do not distinguish between descriptive and injunctive norms because, in the absence of other information, they assume that behavior and the beliefs supporting it are correlated.59 In addition, when descriptive and injunctive norms are in conflict, people conform to the norm that is more salient or convenient, which depends on the context.2 However, Bicchieri and Xiao (2009) examined that when descriptive and injunctive norms are in conflict, descriptive norms significantly predict behavior without finding an explanation for this result.59

To examine the behavioral effects of sustainable dynamic norms, Sparkman and Walton (2017) use five experiments on sustainable behaviors, such as meat consumption and water use, and find that exposure to dynamic descriptive norms can inspire behavioral change and lead to increased sustainable behavior among individuals, even if a contrary static norm already exists.74 They also find that if the static norm is desirable, a dynamic norm can strengthen it further.74Malta, Hoeks, and Graça (2023) examine that the use of dynamic norms increases conformity and has a positive effect on the support for sustainable policies.83 However, the behavioral influence of dynamic norms can depend on the behavior that is endorsed or engaged in before the norm message is communicated.83

There may be a gap between the collectively beneficial level and the preferred self-interest level.2 Social norms are useful in helping groups overcome collective action problems, and therefore sustainable norms influence a range of environmentally friendly behaviors that would suffer from concerns about acting alone when collective action is needed, such as adopting sustainable technologies.23,84,85 So, communities frequently organize and self-regulate to reach the collectively beneficial outcomes.2 Since sustainable behavior often requires collective action to realize the benefits, according to White, Habib, and Hardisty (2019) a descriptive message about the behavior of others combined with collective efficiency will increase the likelihood to engage in sustainable behavior.78 Thus, social norms can be more effective when the behavior benefits other individuals.69

Setting the focus more specifically on the business context by examining the influence of social norms on the sustainability adoption in institutions, Caprar and Neville (2012) propose a model that takes into account the double effect of culture.6 They suggest that culture influences both the spread of sustainability-relevant institutions and the conformity to pressures of the institutions, thus combining the findings of cultural and institutional perspectives on sustainability adoption.6 They suppose that institutions are seen as the formal guiding elements, such as laws, and culture is seen as the informal one, including values and norms, which appear to be an important factor influencing the adoption of sustainability, acting via multiple mechanisms.6

An increased number of norms compatible with sustainability principles will increase the likelihood of sustainability adoption, but institutional pressures promoting sustainability may also carry cultural preferences that are inconsistent with the local culture.6 Thus, variations in sustainability adoption can be subscribed to cultural differences.86 Certain principles of sustainability are more compatible with certain cultures.6 The pre-existing culture of a group of people or organization, which includes social norms, facilitates or hinders the adoption of institutional pressures for sustainability.6 There are also significant differences between developed and emerging countries in the adoption of sustainable practices.6 Thus, the national system, which reflects national characteristics in the adoption of sustainability, is important.6 Therefore, increasing the amount of sustainability-relevant institutions to increase sustainability adoption may be an inefficient approach that ignores the cultural perspective.6

Ciocirlan and colleagues (2020) discover that personal norms predict sustainable behavior in the business context.87For instance, personal norms are expected to directly influence managers’ adoption of sustainable practices.61 In addition, individuals seen as leaders, which could be managers, but also other individuals who are suitable for leadership, have the power to shape group norms and behavior, if they are seen as social referents and represent sources of normative information.37 Social referents are mentioned above and can be associated with the role of leaders in various situations, as they are psychologically salient and therefore more influential on others’ norm perception.37Different scholars examine the importance these leaders can play in changing behavior, among other things in the workplace, by exerting social influence and persuasion through emotions, personal connections, or ease of personal identification.31,37 Leaders can influence a norm regardless of where it is in the life cycle, from diffusion to abandonment.31

2.3.4 Moderators

The moderators that amplify, weaken, or change the strength of social norms influencing sustainable behavior are highlighted in this chapter. First, individual factors are examined, before setting the focus on cultural factors. An overview of the factors is visualized in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Moderators of Sustainable Social Norms, Own illustration.

The degree to which social norms influence sustainable behavior at the individual level is moderated by several situational or individual factors, including the characteristics of the individual, the specific norm, the reference group, the social and physical context in which the behavior occurs, or the activated self-construal of the individual, which is the focus of this thesis.2,20 Self-construal theory suggests that an individual’s self comprises two dimensions in terms of one’s relationship with others: the independent (individual) self, which is concerned with one’s own goals and attributes rather than the thoughts or feelings of others, and the interdependent (collective) self, which is associated with a sense that the self and others are intertwined.88 Both types can coexist within individuals, with one dimension likely to be more dominant.88 The level of the self-construal can be manipulated, for example, through text variations using appropriate pronouns that lead individuals to focus on the emphasized level of the self.89,90 Saracevic and Schlegelmilch (2021) state that the moderating role of the self-construal remains unclear since scholars disagree about whether norm compliance depends on the activated level of the self-construal.81 The unresolved moderating role of self-construal on the impact of social norms on sustainable behavior is investigated below.

Descriptive norms are supposed to influence sustainable behavior when both levels of the self are activated.90 However, Saracevic, Schlegelmilch, and Wu (2022) find no significant relationship between descriptive norms and the self-construal.89 Incorporating injunctive norms, White and Simpson (2013) highlight that different appeals are more effective depending on the self-construal: when the interdependent level is activated, injunctive and descriptive appeals are more effective than benefit appeals in encouraging sustainable behavior, and when the independent self-construal is activated, self-benefit and descriptive appeals are effective.90 In addition, by providing valuable information about appropriate action, they find that descriptive appeals are particularly effective when the context is ambiguous and the individual self-construal is activated.90

White, Habib, and Hardisty (2019) do not concentrate on one specific norm concept, but find that when the self-construal is interdependent, sustainable behavior increases.78 An independent self-construal leads to personal attitudes having an important influence on pro-environmental behavior, whereas in the interdependent self-construal, social norms are a greater predictor, indicating a moderating role of the self-construal.91 Although scholars find a moderating role of the self-construal on the effectiveness of social norms and sustainable behavior, some scholars only focus only on descriptive norms or distinguish between personal and social norms, so there is no comprehensive review of the moderating effect of self-construal and culture on all factors of the relationship between norms and sustainability.81

Yang and colleagues (2024) note that the moderating role of the self-construal is rooted in cultural considerations, as the interdependent and independent self-construals apply to individualistic and collectivistic cultures.10 In a collectivistic culture, individuals perceive themselves as part of the collective and are more inclined to conform to group norms, whereas in individualistic cultures, individuals prioritize the interests of themselves and their immediate families.5,82 Individuals in collectivistic cultures show norm compliance regarding sustainability, whereas the influence of descriptive and injunctive norms on the sustainable behavior of individuals from individualistic cultures differs.89,92Bergquist, Nilsson, and Schultz (2019) argue in the opposite direction that social norms are more influential in individualistic than collectivistic cultures.93 Other scholars find no significant moderating effect of collectivistic or individualistic cultures on the predictive strength of descriptive or injunctive norms on pro-environmental behavior.75Saracevic, Schlegelmilch, and Wu (2022) examine the relationship between collectivistic and individual cultures and the interdependent and independent self-construal, and make recommendations about which normative messages should be communicated based on the culture and the self-construal.89

With regard to cultural factors, the tightness or looseness of cultures affects the strength of social norms and the tolerance and sanctioning of deviance from the norm differently.6,94 It depends on the background conditions that shape the rules, sanctions, and institutions of societies and influences the role that social norms play in the lives of individuals.35 Tighter cultures emerge through, for example, population density, scarcity of natural resources, wars, or exposure to disease, and therefore face more historical and current risks that increase the need for strong norms.2,35,94People living in tighter cultures have a stronger goal of avoiding mistakes and are characterized by more sanctioning of the self and others.35 Thus, tight cultures are typically characterized by stronger norms, less tolerance for deviation, and more stringent norms regarding monitoring and compliance than loose cultures.2,94 Therefore, the difference refers to the cultural tendency either toward adherence to social norms, as observed in tight cultures, or toward greater tolerance for deviance and norm violation, as observed in loose cultures.6,94 In loose cultures, social influence is seen as a less powerful factor in influencing individual behaviors than in tight cultures.23,94 In tight cultures, institutions can be built on existing cultural norms, whereas in loose cultures, a focus on economic benefits or other alternative mechanisms may be more efficient due to the low sanctioning in respect to compliance with norms.6 Overall, the evidence shows a moderating role of the tightness-looseness of cultures.6 Thus, the influence of social norms can be contingent on the cultural background.95

2.4 Central Research Areas on Values

Key research areas in the concept of values in relation to sustainability are explored in the following. These encompass fundamental theories and models that lead to measurement methods, the formation of sustainable values, the behavioral impact of sustainable values on sustainable actions and altruism, and factors that strengthen or weaken the relationship between values and sustainability. First, the concept of values is outlined by examining different constructs, followed by an investigation of the measures of values and sustainable values. Then, the drivers and outcomes of sustainable values are examined, and finally, the moderators are analyzed.

To explore the concept of sustainable values, it is first necessary to introduce different constructs. There are various understandings of social values that cannot be integrated into a single framework, and highlighting them would exceed the scope of this thesis.43 However, Sivapalan and colleagues (2021) propose two distinct value systems that offer insights into green consumer behavior: personal and consumption values.96 Personal values are based on the aforementioned value bases theory and include altruistic, biospheric, and egoistic values, while consumption values associated with green consumption incorporate emotional, social, epistemic, ecological, functional, economic, conditional, and aesthetic values.53,96 The consumption values are not independent of personal values, but rather personal values influence the strength of consumption values.96 The two constructs are visualized in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Constructs of Values, Own illustration, based on Sivapalan and colleagues (2021).96

In addition to the constructs of personal and consumption values, Kenter and colleagues (2019) distinguish between an independent construct of values, referred to as individual values, and an aggregated construct of individual values, referred to as social values, and investigate the relationships between them.43 In particular, the aggregation of individual values from social values is examined, where they propose five ways of the relation between social and individual values: individual and social values are distinct but may overlap, social values are a subset of individual values, social values predict individual values or vice versa, or a dynamic view, where values move from the social to the individual level and vice versa.43

2.4.1 Measures

There is no universal scale for measuring values, or specifically sustainable values: some scholars measure them with sets of attitude questions in specific domains, while others use scales examined below.26 Dietz, Fitzgerald, and Shwom (2005) note that the measurement method of values used in a study provides the working definition of values in that study, increasing the need to explore different measurement methods.17 To provide an overview of possible ways to measure values, this chapter focuses on different scales, their potential disadvantages, and alternative tools to measure values. Some of the scales and tools do not directly measure sustainable values, but the results can be related to sustainability.

In terms of measuring cultural values, Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions Theory of Values originally consisted of four dimensions: power distance, individualism/collectivism, masculinity/femininity, and uncertainty avoidance, but was expanded to include a fifth and sixth dimension: short/long-term orientation, which captures the difference between values associated with past and present orientation and those associated with future orientation, and indulgence versus restraint.97,98 The theory was developed using data collected through questionnaires from International Business Machines Corporation (IBM) employees in more than 50 countries and examines cultural differences in organizations.98 Using the theory, the Values Survey Module measures all six dimensions in one questionnaire.99However, the scale is not appropriate to measure individual values and link them to behavior.40 The Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness Research Program (GLOBE) builds on Hofstede’s dimensions and adds new dimensions of future orientation, human orientation, performance orientation, and assertiveness; it distinguished between in-group and institutional collectivism, and it redefines masculinity-femininity as gender equality.6,100 The GLOBE study measures nine core dimensions of cultures, separated into values and practices through questionnaires.6,100 Compared to Hofstede, the GLOBE study focuses more on business practices in its questions, such as risk-taking in business decisions when examining uncertainty.100 To obtain access to the questionnaires invented by GLOBE, the GLOBE project needs to be contacted directly.101

To study individual value differences, S. H. Schwartz suggests the Schwartz Value Survey (SVS) and the Portrait Value Survey (PVQ), which build on his Theory of Basic Human Values defined above.26,40 The SVS consists of 56 survey items that participants are asked to rate on a nine-point scale that indicates how important a stated value is as a guiding principle in an individual’s life.17,40 These items are assigned to the ten value orientations mentioned in Schwartz’Theory.40 However, individuals with little or no education might have difficulty answering the questions.40 Resulting from values connected to the environment, the Environmental-SVS is an adapted and shortened version of the SVS, where participants are asked to indicate on a nine-point scale, how important 16 different values are as a guiding principle in their lives.102

The PVQ consists of 20, 29, or 40 verbal portraits of different individuals describing this person’s goals, aspirations, or wishes and asks respondents to indicate how similar they are to that person, with responses ranging from very much like me to not like me at all.40 The result of the PVQ is the implicit relevance of the value through the comparison of the self with the image, so that the respondent’s values are derived from the values of the individuals they describe as themselves.40 This survey is more concrete and contextualized than the SVS by providing descriptions of people rather than abstract value terms, therefore no self-conscious reports of values take place and it can be used for all segments of the population.26,40 The PVQ is used in telephone interviews, face-to-face interviews, internet surveys, or written questionnaires.40 By providing two measurement methods for his theory, Schwartz shows that the support for his theory is not dependent on the measurement instrument.26 However, the surveys do not directly focus on altruism as a central feature when linking values to environmentalism.17 Therefore, Dietz, Fitzgerald, and Shwom (2005) collect various scales supplementing the original Schwartz’ items or using alternative sets of items.17 For instance, one supplementation adds two additional items to capture the distinction between humanistic and biospheric altruism and invents a short scale of 15 items.103

De Groot and Steg (2008) use the value categorization into egoistic, altruistic, and biospheric dimensions of the Value-Bases Theory, thereby distinguishing values that concern the environment as biospheric values and other self-transcendent values as altruistic values, to measure environmental values.104 They also present an adapted value instrument to empirically distinguish the three value orientations.104 In addition, they examine the relationship of the value orientations to behavioral intentions regarding pro-environmental actions, and invent and evaluate among samples a short rating scale to measure the three value orientations.104

Inglehart’s theory of materialistic and post-materialistic values suggests that individuals set their focus on the most important unsatisfied needs at a time, which change with the process of industrialization.17,105,106 In industrializing countries, individuals are assumed to hold materialistic values, which prioritize economic and physical security, whereas individuals in postindustrial countries hold post-materialistic values toward quality of life, which refer to the needs for belonging, esteem, and self-realization.17,105 The corresponding values survey asks participants to rank their preferences among a contrasting set of possible goals for their country that reflect a materialistic or a post-materialistic orientation to national priorities and checks for changing values.17,107 The higher a country scores on post-materialism, the greater is the concern of its members for the environment.108 The survey is considered the easiest measure to implement since, depending on the scale, only four or twelve questions have to be incorporated into the study, depending on the scale.17,40 However, the items on this scale are sensitive to prevailing economic conditions; the scale measures values only indirectly by asking about preferences among goals for one’s country rather than personal goals, and it measures only a single value diemension.40

The NEP is a social-psychological measure of environmentalism which measures broad beliefs about the biosphere and the effects of humans on it in relation to the relative general awareness of environmental conditions.46,48 Participants are asked to rate the extent to which they agree with 15 items referring to the relationship between humans and the environment.48 For the rating a scale from one, indicating total disagreement, to five, indicating total agreement is used.48

Regarding the critique, one difficulty with value surveys is that they are likely to capture values as well as marginal preferences, but in unknown proportions: There is a negative correlation between values and practices reported by GLOBE, which implies that the more a goal is satisfied, the less individuals express a desire for its further realization.109 This is only solvable by designing questions inducing participants to answer with their general inclinations rather than talking about changes in their current situation, focusing on desired states as opposed to desired changes.109 When asking respondents to rank values as guiding principles in their lives independently of specific contexts, these values will remain stable over time, but if values should be ranked when specific issues arise, then there may be discrepancies between the previously stated values and the concrete values in the situation.110 Furthermore, according to Nazirova and Borbala (2024), most of these surveys have been unsuccessful and have not produced reliable results since many value items ignore values transcend features distinguishing them from concepts such as norms.26 In addition, some scales are too abstract to be used with less educated groups, and they concentrate on specific areas of life.26 Finally, Schaefer, Williams, and Blundel (2020) state that individuals activate sets of values in situations because the behavior depends on a combination of values rather than single values, which increases the importance of considering configurations of value domains when focusing on environmental engagement.52

It is also possible to measure values through regressions or experiments, such as the dictatorgame.17 Experiments can be powerful by measuring the actual behavior of participants, whereas surveys are prone to measurement error because of a discrepancy between the statements of individuals and their actual behavior.17 However, measuring values through experiments has not been connected to environmentalism and has less external validity and generalizability.17 In some cases, under strong conditions, prices are influenced only by supply and demand, and thus, prices may reflect values allowing their measurement.17

2.4.2 Drivers

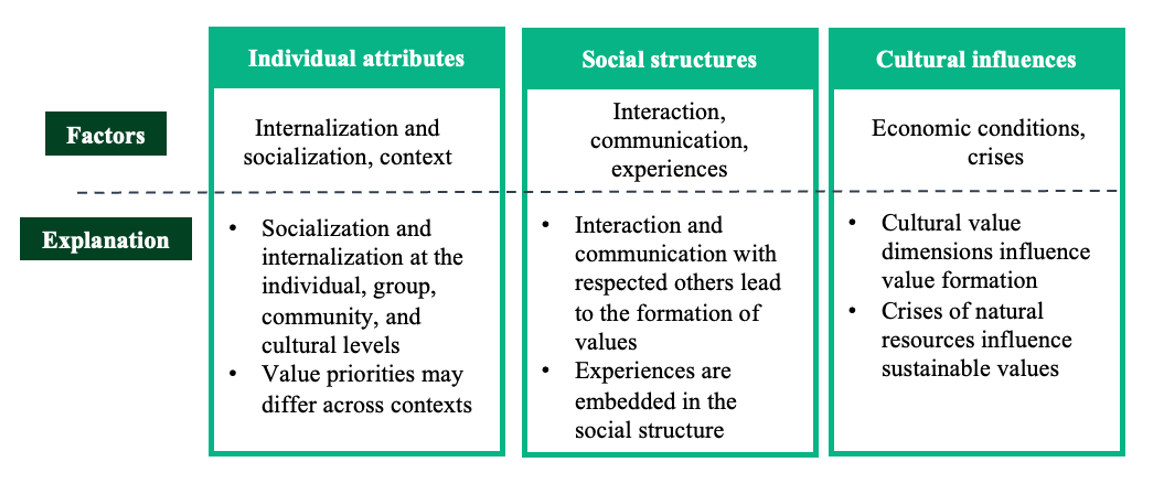

The focus of this chapter on the drivers of sustainable values is set on their formation by changing existing values toward sustainability. Values are assumed to be established early in life, thus examining the initial formation of values would exceed the scope of this thesis.87 According to Yang and colleagues (2024), the formation of values depends on three factors consisting of individual attributes, social structures, and cultural influences.10 This chapter first investigates the stability of values before examining the three factors related to the formation and change of values toward sustainability as seen in Figure 6. Most of the drivers examined in this chapter are related to values in general but can be applied to the domain of sustainable values.

Figure 6: Drivers of Values and Sustainable Values, Own illustration.

The VBN theory views values as deeply rooted and established early in life.87 Thus, values are seen as relatively stable over time.17 Schuster, Pinkowski, and Fischer (2019) examine the stability and change of values in adulthood: They suggest a moderate to high rank-order stability of values, even with life-changing transitions as seen in Table 2, but at the same time examine small changes, with aging as a possible theoretical explanation for the changes.111 Kendal and Raymond (2018) examine changes in the context of the individual and find that values can change through immigration and emigration from a group over time, through environmental shocks, social-cultural changes, and within the individual through maturation.112 Some researchers suggest major changes in values in early adolescence and also in adolescence without any crises, since values are developed in this period as identity forms.113,114 Thus, values may emerge because of a developmental process that is completed by adulthood but life experiences, transitions, the influence of others, or maturation affect them to some extent.111 However, the influence of life transitions on values is inconclusive.111 Although, some scholars and theories assume that individuals have a stable value system, others suggest a fluctuating system in which individuals do not apply the general abstract value priorities to specific issues, but rather modulate and re-evaluate the importance assigned to values.110 Thus, the emphasis placed on values can be shaped and reshaped over the course of an individual’s life.17

Table 2: Impact of Life Transitions on Values, Own illustration, based on Schuster, Pinkowski, and Fischer (2019).111

| Transition | Change in Values |

| Educational Transitions | No consistent pattern of mean-level value change.111 |

| Migration (immigration and emigration) | No proven way of processes or direction of value change.111,112 |

| Parenthood | Small but significant shift toward conservation values among mothers.111 |

| War Zones | Stable values, where small changes are not systematic or predictable.111 |

| Maturation | Changes in values during early adolescence and adolescence.112,114 |

After examining the stability of values, individual attributes are investigated as a driver of sustainable values. These focus on the socialization, internalization, and the context of sustainable values. Individuals develop value priorities that simultaneously address their basic needs, the opportunities and barriers, and the perceptions of what is legitimate or forbidden in their environment.40

Values are acquired and transferred through socialization and internalization processes.43 Kenter and colleagues (2019) propose a figure that visualizes the difference between the socialization and internalization of values, reflecting the individual, group, community, and cultural levels, and also examine the transfer of values between social levels: The internalization process begins with the individual holding certain values and interacting with the group level through feedback that strengthens or weakens the relationships of values, which then interacts with the community and cultural levels, leading to the internalization of specific values.43 Internalization at the personal level is achieved by individuals observing interpersonal dynamics and adjusting their value orientations to align with the social values of the group.43,115 The internalization process depends on personal reflection and intra-individual deliberation.43 The socialization process happens in the opposite direction and leads to the transfer of values from the cultural to the individual level.43 The values that emerge from socialization are supposed to be solidified through social learning and social norms.43,116 Social learning in sustainability science functions as a link between the individual and the collective, and influences the understanding and change of social values, with individuals with a lower understanding of social values being more likely to change their values after deliberation.117

In terms of the context, there is a difference between believing that values exist as discrete entities that are pre-formed and held by individuals, and believing that they are only coming into existence when manifested or in deliberation.118,119 The weight given to different values may depend on the role individuals are in when making the decision: Dietz, Fitzgerald, and Shwom (2005) differentiate between selling a car to a close relative or to a stranger and note that this can also be applied to contextual cues influencing the protection of the environment.17 Thus, in contrast to the suggestion that important values in a value system are activated when an issue is raised, individuals reconstruct their value priorities within a specific context.110 Therefore, the drivers of sustainable values should also take the context into account.17