Authors: Jacek, Bednarek, Philipp Buerfeind, Marlon Janßen, Jannik Wiegrefe

Last updated: December 20, 2022

1 Definition and relevance

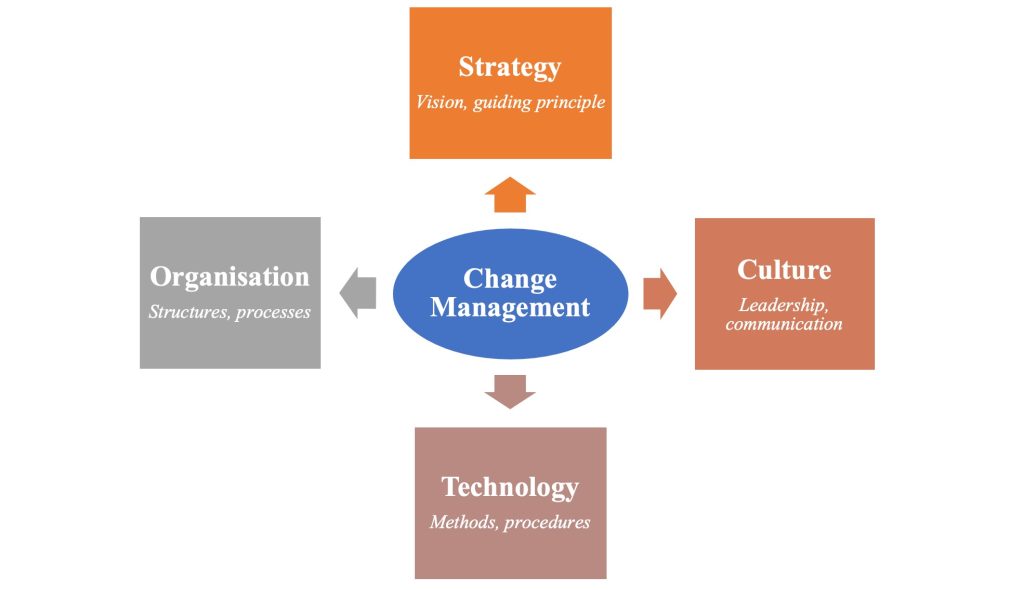

The concept of change management developed from organizational development or organizational change and deals with the transition or transformation of organizational objectives, processes, core values and technologies with the aim of achieving sustainable improvement. Change management is also understood as a systematic approach that includes all measures and activities that contribute to a substantive change for the implementation of new strategies, structures, systems, processes or behaviors in an organization (see figure 1). 1Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018). Change management is about achieving an optimal design of the path from the starting point to the goal and not the simple application of methods and procedures of strategic goal planning. 2Lauer, T. Change Management: Grundlagen und Erfolgsfaktoren. (Springer Gabler, 2019). Failing to adopt these changes in a company’s structure could result in problems like e.g. aggravation of existing problems of an organization, survival of the business (model) and having an impact on society and the environment. 3Ha, H. Change Management for Sustainability. (Business Expert Press, 2014).

In the context of sustainable development, firms need to consider the economic, environmental, and social dimensions equally, because if the organizational structure and management system are not modified and designed appropriately, organizations may not profit from all the benefits associated with sustainability performance. 5Ha, H. Change Management for Sustainability. (Business Expert Press, 2014). The problems and challenges of the ever-advancing climate change are a central and daily topic with global relevance. The current global warming of the earth due to the emission of greenhouse gases affects humans and our environment. The quality of the air is declining, the polar ice caps are melting, biodiversity is decreasing, and habitats and conditions for animals and plants are changing. Natural disasters such as hurricanes, heat waves, droughts and floods are becoming more frequent all over the world. 6Große Ophoff, M. Herausforderung Klimaschutz: Warum wir keine Zeit mehr haben. in Unterwegs zur neuen Mobilität: Perspektiven für Verkehr, Umwelt und Arbeit (Flore, M., Kröcher, U. & Czycholl, C.) 19-31 (oekom Verlag, 2021). Topics such as global warming and the trend towards sustainability have therefore shaped political, economic and social discourse for years. 7Fazel, L. Akzeptanz von Elektromobilität: Entwicklung und Validierung eines Modells unter Berücksichtigung der Nutzungsform des Carsharing. (Springer Fachmedien, 2014). In view of the ever-increasing climate change, rapid and effective countermeasures to reduce emissions are an ecological and economic necessity. 8Flore, M., Kröcher, U., & Czycholl, C. Unterwegs zur neuen Mobilität: Perspektiven für Verkehr, Umwelt und Arbeit. (oekom Verlag, 2021). Consequently, the focus is stronger than ever on megatrends such as sustainability, digitalization, efficiency and increased environmental awareness with concern for natural and human resources. 9Fazel, L. Akzeptanz von Elektromobilität: Entwicklung und Validierung eines Modells unter Berücksichtigung der Nutzungsform des Carsharing. (Springer Fachmedien, 2014)., 10Cesnuityte, V., Klimczuk, A., Miguel, C., & Avram, G. The Sharing Economy in Europe: Developments, Practices, and Contradictions. (Palgrave Macmillan (Springer Nature Switzerland AG), 2022)., 11Fitte, C., Berkemeier, L., Teuteberg, F., & Thomas, O. Elektromobilität in ländlichen Regionen. in Smart Cities/Smart Regions – Technische, wirtschaftliche und gesellschaftliche Innovationen (Gómez, J. M., Solsbach, A., Klenke, T. & Wohlgemuth, V.) 37-52 (Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH, 2019). In the context of bringing sustainability into the change management, the company aims to achieve the financial as well as the environmentally sustainable momentum of changes in business. 12Ha, H. Change Management for Sustainability. (Business Expert Press, 2014).

Especially difficult market conditions, such as the challenges posed by the global COVID-19 pandemic since 2020, show that a flexible and dynamic adaptation of processes and changes in the mindset of companies via change management is important to remain in the market and to be able to establish themselves in the long term. In addition, due to the development of global climate change, it is increasingly important to consider sustainability aspects as a central driver in change management and to design processes and structures as effectively as possible. 13Ha, H. Change Management for Sustainability. (Business Expert Press, 2014). This can only be achieved if the majority of employees have a deep understanding of this change in order to ensure the long-term performance of a company and to comply with new environmental conditions or laws (e.g. the European Green Deal or the Supply Chain Act). Consumer awareness has also changed and the demands of customers on companies regarding sustainable products and services have increased enormously in recent years. Therefore, companies should act as role models for a conscious and responsible approach to our planet and our society.

2 Background

The historical background of change management is a relevant research focus for the scientific disciplines of social and organizational psychology as well as organizational and management studies (economics). It extends from the scientific management founded by Frederick W. Taylor in 1911 to today’s organizational development. 14Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018). Scientific management dealt with increasing operational efficiency and optimizing management, labor and enterprise through strict specialization and standardization. The research disciplines are very diverse. The Hawthorne studies, among others, showed that social factors have a great influence on work behavior and work motivation, as do employee surveys and supervisor evaluations for the joint identification and implementation of necessary changes. 15Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018). Within the framework of sensitivity training, the influence of individual behavior on a group was analyzed. 16Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018). Finally, organizational development can be described as a planned systemic approach controlled by managers with a view to the entire system or organization. It aims to increase corporate health through planned influence on the corporate structure, processes, strategy and culture. 17Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018).

2.1 Stage/phase models for change management

For such a flexible, dynamic and individual concept as change management, there is no optimal or universally valid model. Therefore in the literature, there are various stage/phase models for change management, such as the eight-stage model according to J. Kotter from 1996, the seven-phase model by R. Streich from 1997, the Action Research Model, the five-step positive model and the Six Main Change Models and Theories discussed by Kezar. 18Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018)., 19Ha, H. Change Management for Sustainability. (Business Expert Press, 2014). The cornerstone of all these more detailed models is the three-phase model according to K. Lewin from 1947. This consists of the three key elements unfreezing, moving and refreezing. 20Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018). According to his conception, there is an actual state consisting of habits, certainties and traditional procedures as well as legal, political, economic and social conditions, that could destabilize this state. In the first of the three phases, the aim is to temporarily unfreeze this actual state, generating awareness of change among both, the actors and those affected by the change. In the second phase, changes are made and certain areas/processes move to a new level that is (at least temporarily) higher than the previous actual state. In the third phase, this state resulting from the changes in phase two is refrozen. This is intended to bring about the changed aspects and their long-term implementation in attitudes and behaviors. 21Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018).

All these and many other models also take up the basic assumptions of the three-phase model according to Lewin. However, the three-phase model is in part insufficient to track today’s very complex dynamics of change management. Thus, the eight-stage model according to Kotter (see figure 2) is usually used today, because it specifies the steps in more detail. 22Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018).

In the first step, the management will assess internal organizational strengths and weaknesses, considering market activities and the level of competition, to identify the status quo and the potential for improvement. Subsequently, it is of central relevance to create an awareness of the need for change among the employees and thus establish a sense of urgency. The second step is to appoint an influential and powerful guiding coalition, which is a group of competent and committed stakeholders who are able to lead and implement the change process, e.g. by encouraging the other group members to work closely together as a team. The third step is to develop a vision and strategy, where the vision represents concrete guidelines for the direction of the strategy development and the implementation of concrete action plans (linked to sustainability). The fourth step is one of the most important steps in change management. Here the change vision and the newly developed strategy are communicated in detail by the guiding coalition to all relevant stakeholders (especially employees) through various channels. 24Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018)., 25Ha, H. Change Management for Sustainability. (Business Expert Press, 2014). These first four steps correspond to the first phase according to Lewin (unfreeze). 26Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018). It is important to align as many stakeholders as possible behind the desired change. Therefore, the fifth step of the model is to minimize obstacles in the change process, to change structures and systems that hinder change and to encourage and empower employees to actively participate in the change process as well as encourage risk-taking, creativity and innovation. In the sixth step, adequate short-term wins are generated, each with a defined beginning and a concrete end, and are made measurable and visible to all participants. In this way, those who adopt new ways of behaving and participate positively in the change process can be rewarded. The seventh step consists of consolidating gains and producing more change. The partial successes that have already been achieved should be used to change further structures, processes and systems. This can, on the one hand, be done by training, promoting, and developing stakeholders or on the other hand by employing external change agents, who can contribute to the achievement of the vision and foster the change process with new (external) initiatives, interventions and in-depth knowledge. 27Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018)., 28Ha, H. Change Management for Sustainability. (Business Expert Press, 2014). Steps five to seven correspond to the second phase according to Lewin (moving). 29Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018). The eighth and final step is to help stakeholders understand the link between the new behaviors and the improvement in the performance of the organization. Finally, the new behaviors, practices and approaches are anchored in the culture of the organization. The sustainable supply of junior staff with an affinity for change plays a central role in the future development of the company. Step eight corresponds to the third phase according to Lewin (refreeze). 30Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018)., 31Ha, H. Change Management for Sustainability. (Business Expert Press, 2014).

2.2 Principles of change management

To implement change management successfully in a company, four central principles must be followed. The first principle is to create an understanding of change by strongly promoting the benefits for the organization and how it will affect people positively. It needs to be enough discomfort in the old procedures so that people will feel more confident with the new approach. The second principle is adequate planning of the change, as change varies from organization to organization and project to project. Here is particularly important who suits best to be involved in the design and execution of the change. The third principle is to implement the change, e.g. by putting the change into practice through the eight-step model according to Kotter (see chapter 2.1). As many actors as possible should be involved in the change, including those who initially refuse or are skeptical, to convince them of the new practices so that they can become the norm in the long run. The fourth principle is to communicate the change to the stakeholders clearly and appropriately, so people understand what to do and why. Doing so, the AKDAR principle (Awareness-Desire-Knowledge-Ability-Reinforcement) can be helpful. 32Maiti, M. What is Change Management Educationleaves https://educationleaves.com/change-management/ (2021).

3 Practical implementation

3.1 Determination of change to organizational sustainability

This chapter explains how the concept of change management in terms of sustainability can be practically implemented. Before dealing with specific processes, their pros and cons as well as best practices, the chapter will take a closer look at general considerations that should be determined prior to the execution of the implementation process.

To choose an adequate change method, the literature noted the importance of a clear definition of the change type as well as change enablers. A change type can be classified into mainly two dimensions: the change scale and the duration of change (see figure 3). The changing scale distinguishes large and small scales and was defined “as the degree of change required to reach the desired outcome”. 33Al-Haddad, S. & Kotnour, T. Integrating the Organizational Change Literature: a Model for Successful Change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, Vol. 28 (2), 234–262 (2015). Large-scale changes include an all-embracing transition of processes and behaviors within an organization that influences the output. 34Oldham, J. Achieving large system change in health care. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 301 (9), 965-966 (2009). Next to the organization itself, large-scale changes also cover stakeholder involvement, emphasizing the necessity of visionary leadership as well as cooperation in order to succeed. 35Margolis, P. A. et al. Designing a Large-Scale Multilevel Improvement Initiative: The Improving Performance in Practice Program. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, Vol. 30 (3), 187–196 (2010). In literature, large-scaling changes are viewed as controversial, because the large extent of those ambitions needs to take into account the decentralized structures of a company, more concretely differences in unit cultures. 36Stock, Byron A. Leading Small-Scale Change. Training & Development (Alexandria, Va.), Vol. 47 (2), 45 (1993). Furthermore, it is commonly believed, that the success of large-scaling changes depends on the level of organizational resources. 37Bennett, W.L. & Segerberg, A. The logic of connective action. Information, Communication & Society, Vol. 15 (5), 739-768 (2012). In contrast, smaller changes are perceived as changes of lower dimension and importance and are more applicable to specific projects (e.g., quality improvement projects). 38Berwick, D. M. Developing and testing changes in the delivery of care. Annals of Internal Medicine, Vol. 128 (8), 651-656 (1998).

The change duration can be defined as “the period over which changes take place” and change processes can be either implemented long- or short-term. 40Al-Haddad, S. & Kotnour, T. Integrating the Organizational Change Literature: a Model for Successful Change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, Vol. 28 (2), 234–262 (2015). Long-lasting change processes are often characterized as challenging and demand a high level of leadership in combination with active employee involvement throughout the change process. 41Rachele, J. S. The Diversity Quality Cycle: Driving Culture Change through Innovative Governance. AI & Society, Vol. 27 (3), 399–416 (2012). This results in the importance of the consideration of human behavior as well as the requirement of preceding leaders. Because of previously described factors, long-term change processes are often seen as less successful in literature. Additionally, a short-term process is more successful when the responsiveness of companies for smaller changes is faster. The faster the reaction, the more probable a company can reach competitive advantages. 42Ulrich, D. A new mandate for human resources. Harvard Business Review, Vol. 76 (1), 124-134 (1998). However, short-term duration is most effective in smaller, steadier processes. 43Berwick, D. M. Developing and testing changes in the delivery of care. Annals of Internal Medicine, Vol. 128 (8), 651-656 (1998).

However, as organizational sustainability is seen as a key strategy, that considers economic, environmental and social dimensions to contribute to the sustainability equilibria, small scaling and short-term changes might not live up to the requirements. The goal of organizational sustainability requires the inclusion of all organizational elements, such as production, strategy and management, governance, assessment, and reporting which simply cannot be covered by small scaling in the short term. 44Lozano, R. Proposing a definition and a framework of organizational sustainability: A review of efforts and a survey of approaches to change. Sustainability (Switzerland), Vol. 10 (4), 1–21 (2018). That is why it is important to be aware that sustainability can be implemented best through large scaling and therefore implies arising challenges mentioned above. Furthermore, the implementation of organizational sustainability will require a lot of time and must especially consider human behavior and leadership. 45Al-Haddad, S. & Kotnour, T. Integrating the Organizational Change Literature: a Model for Successful Change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, Vol. 28 (2), 234–262 (2015).

As the implementation of sustainability within an organization and the associated change process seem to be challenging, it is important to think about promoters of organizational change to increase the probability of success. 46Chrusciel, D. & Field, D. W. Success Factors in Dealing with Significant Change in an Organization. Business Process Management Journal, Vol. 12 (4), 503–516 (2006). It is crucial, that the evaluation of change enablement is at the beginning of the implementation process. In general, an organization must analyze its environmental conditions, which will directly affect the change process. Those conditions most importantly imply employees’ sense of change requirements within the organization. 47Al-Haddad, S. & Kotnour, T. Integrating the Organizational Change Literature: a Model for Successful Change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, Vol. 28 (2), 234–262 (2015).

Three general aspects a reasonable change strategy should consider were suggested by Anderson and Ackerman (2001, see figure 4): content, people and process. By naming content, they were taking the strategy itself, systems, technologies and work practices into account. The aspect of people addresses the role of humans involved and their behavior in the change process. The focus on the personal dimension enhances the probability of a successful change process. Lastly, the process refers to specific operations required in the implementation process. Related to the change toward organizational sustainability those factors previously mentioned are also playing a crucial role to facilitate the process and will be directly addressed in the chapter that deals with the method of implementation. 48Anderson, D. & Ackerman Anderson, L.S. Beyond Change Management (Electronic Resource): Advanced Strategies for Today’s Transformational Leaders. (Jossey-Bass/ Pfeiffer, San Francisco, 2001).

Al-Haddad & Kotnour (2015) later reviewed several studies from the literature and finally determined three key change enablers consisting of commitment, knowledge and skills as well as resources. 51Al-Haddad, S. & Kotnour, T. Integrating the Organizational Change Literature: a Model for Successful Change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, Vol. 28 (2), 234–262 (2015).

3.2 Method of implementation

Having determined the change type of sustainability as a large and long-term change process and having considered potential enablers, this chapter is going to provide an overview of methods of implementation. Before presenting methods, the chapter will first take a closer look at the level of organizational culture and corporate governance and determines their role in implementing sustainability through change management. That is followed by the illustration of a conceptual change management method, that collects the most significant overlaps of the methods presented in chapter 2.1 and additional strategies. As a result, a concrete action step plan as well as applicable tools and measures will be presented. Finally, the chapter will close out by addressing some best practices provided by the literature.

3.2.1 Organizational culture and corporate governance

Before processing with the implementation of sustainability, the involvement of cultural aspects is indispensable, as the importance of both is often emphasized regarding the path to success. 52Diaz-Iglesias, S. et al. Theoretical framework for sustainability, corporate social responsibility and change management. Journal of Sustainability Science and Management, Vol. 16 (6), 315–332 (2021). In fact, next to the implementation itself, there is an organizational change, dealing with the levels mentioned. 53Millar, C. et al. Sustainability and the Need for Change: Organisational Change and Transformational Vision. Journal of Organizational Change Management, Vol. 25 (4), 489–500 (2012). Similar to society an organization like a company has its own culture that is underlined by values and norms that define the importance and appropriateness of individual behavior. 54Doppelt, B. Leading Change toward Sustainability. (2nd ed. Taylor and Francis, 2017). Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1546026/leading-change-toward-sustainability-pdf (Accessed: 18 August 2022). In the case of the implementation of sustainability, all actor’s behaviors within a company on every considerable organizational level must be underlined by sustainable principles. 55Kiesnere, A. & Baumgartner, R. Sustainability Management in Practice: Organizational Change for Sustainability in Smaller Large-Sized Companies in Austria. Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland), Vol. 11 (3), p. 572 (2019). A strong role in a sustainable change process is associated with management. Leadership usually serves as an initiator for a change in thinking and should continue their commitment beyond change targets. The challenge for leaders mainly lies in the alignment of sustainability with work practices and strategies. To extend the claim even more, the best leaders expand their focus beyond their organization and try to positively influence their industries. By considering environmental conditions as stated in chapter 3.1, management must focus on employees, customers, policymakers and society. 56Millar, C. et al. Sustainability and the Need for Change: Organisational Change and Transformational Vision. Journal of Organizational Change Management, Vol. 25 (4), 489–500 (2012). Although the integration of sustainable thinking is seen as difficult (will be addressed in 4.1 Barriers), existing values need to be aligned with a more holistic and long-term perspective.

Further change is demanded for the organizational governance system to promote the transformation towards sustainability. Governance in general can be described as “the way information is gathered and shared, decisions are made and enforced, and resources and wealth are distributed”. It is argued that sustainable change requires new or modified governance systems that assure systems thinking, transversal collaboration, employee empowerment and stakeholder engagement. 57Doppelt, B. Leading Change toward Sustainability. (2nd ed. Taylor and Francis, 2017). Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1546026/leading-change-toward-sustainability-pdf (Accessed: 18 August 2022).

3.2.2 Methods of change management and steps of implementation

As stated in chapter 2.1, there were several approaches for the implementation of change proposed over time. To put it in a nutshell, the most important overlapping steps are the analysis of the current state and the creation of a sense of urgency, the definition of clear responsibilities and leadership, followed by the creation and spreading of a vision and finally the implementation and manifestation of successful changes. However, those methods are often criticized because they often fail to reflect the complexity of change and it is not realistic that those steps can always be followed strictly in the suggested order, because of human factors. 58Gilley, A. et al. Change, Resistance, and the Organizational Immune System. S.A.M. Advanced Management Journal (1984), Vol. 74 (4), 4 (2009). A theoretical framework that can be derived from this chapter in combination with influencing factors from chapter 3.2.1, categorized as organizational culture and the governance system, are implicitly addressed when using organizational change strategies. Additionally, strategies can be derived from the elaborated transition steps and are categorized into leadership and involvement, human resources as well as communication and assessment. 59Klein, N. et al. Factors and Strategies for Circularity Implementation in the Public Sector: An Organisational Change Management Approach for Sustainability. Corporate Social-Responsibility and Environmental Management, Vol. 29 (3), 509–523 (2021).

3.3 Tools

Managers intend to apply the strategies and therefore integrate environmental and social practices in their company. Research has examined a various number of possible management tools. Those tools vary in their orientation as some are more social-oriented and others more sustainability-oriented. As the list of proposed continued to grow in the past, this entry will just focus on a collected sample of some tools with different orientations and impacts on the change process to sustainability. More concretely, functional areas like accounting, marketing, production management supply chain management are addressed as well as cross-functional support systems, that are focusing on the companies’ overall goals. 60Johnson, M. P. Sustainability Management and Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: Managers’ Awareness and Implementation of Innovative Tools. Corporate Social-Responsibility and Environmental Management, Vol. 22 (5), 271–285 (2015). General benefits offered by such tools are often related to their usefulness for managers in environmental or social decision-making processes and lead to the overall improvement of social and environmental performance which is mainly driven by awareness and communication. 61Zorpas, A. Environmental management systems as sustainable tools in the way of life for SMEs and VSMEs. Bioresource Technology, Vol. 101, 1544-1557 (2010). Further aspects improved by tools are the operationalization of sustainable strategies enabled through new measures and feedback channels and the ease of organizational learning abilities. 62Steward, H. & Gapp, R. Achieving effective sustainable management: A small-medium enterprise case study. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, Vol. 21 (1), 52-64 (2014).

3.3.1 Code of Conduct

Set up on chapter 3.2.1, there are different ways to influence an organization’s culture. To ensure, that different entity levels including top managers act in favor of the companies’ values and norms it may be useful to formalize them into written rules. Generally, there are several strategies to affect ethical behavior and among them, there is one concrete sustainability management tool affecting sustainable governance: the Code of Conduct. The code of conduct is socially oriented and is implemented through a compliance strategy. Those highlight individual behavior and are characterized by the supervision of management, employees, or even certain stakeholders to maintain ethical standards. For supervision purposes, external auditors can be assigned the task of compliance audits. Common steps are the communication of standards and principles, falling under organizational sustainability. In fact, these are often minimum requirements of behavior entailing reporting in case of any unethical behavior. 63Doppelt, B. Leading Change toward Sustainability. (2nd ed. Taylor and Francis, 2017). Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1546026/leading-change-toward-sustainability-pdf (Accessed: 18 August 2022)., 64Graafland, J., v. d. Ven, B., Stoffele, N. Strategies and Instruments for Organising CSR by Small and Large Businesses in the Netherlands. Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 47, 45-60 (2003).

Two additional strategies suggested by the literature are the integrity strategy and the dialogue strategy. The integrity strategy is about managers and employees fulfilling their tasks in a responsible way based on their own responsibility and integrity, whereas the dialogue strategy is more focused on the interests and values of the stakeholders. Regarding the change toward organizational sustainability, a mix of all three strategies might facilitate the needs examined in chapter 3.2.1. 65Graafland, J., v. d. Ven, B., Stoffele, N. Strategies and Instruments for Organising CSR by Small and Large Businesses in the Netherlands. Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 47, 45-60 (2003). For a sustainable governance system, there are five characteristics that are most dominant. Starting with the first characteristic, all sustainability-oriented governance systems seem to strive for a vision as well as incorporated environmental and social principles. The purpose should be on the same level as other corporate goals. Second, those systems promote a wider distribution of information to increase the knowledge and measurement of the purpose. Furthermore, the involvement of all affected individuals as well as equal sharing of resources are the third and fourth characteristics of a sustainable governance system. Finally, it gives people freedom on the one side, and a framework to operate in for authorities on the other side. Some approaches then tried to take it even further by suggesting more and direct integration of employees and proposed participative decision-making. However, even though it promotes active leadership and employee involvement, those systems are not that easy to develop. Dynamic environmental developments like rising tensions related to environmental degradation or changes in political fields could potentially cause people to demand a return to more patriarchal governance forms. The question that remains is, how governance systems can be created that grant all involved people and institutions similar rights. 66Doppelt, B. Leading Change toward Sustainability. (2nd ed. Taylor and Francis, 2017). Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1546026/leading-change-toward-sustainability-pdf (Accessed: 18 August 2022).

3.3.2 Employee training

To continue the consideration of some tools, this entry wants to highlight employee training as a further important tool, especially orienting to the areas of environment, sociality and sustainability. Besides the rising attention for corporate social responsibility (CSR) in MBA programs, institutions like the UN Global Compact held companies responsible to integrate aspects like environment, sociality and governance into their strategies. Guiding principles that should underline the management education for CSR are purpose, values, methods, research as well as partnership and dialogue. 67Tseng, Y.F., Wu, Y.C.J., Wu, W.H. & Chen, C.Y. Exploring corporate social responsibility education: The small and medium-sized enterprise viewpoint. Management Decision, Vol. 48 (10), 1514–1528 (2010). Employee education could be addressed by workshops themed around the topics of change management and sustainability. Hereby, the addressees could vary, as those workshops could also be conducted for externals like suppliers or business partners. The main purpose as already shined through by UN Global Compact is to raise the awareness and knowledge of the people that are in a relationship with the company implementing organizational sustainability. 68The Global compact leaders summit 2007: The United Nations Global Compact. URL: https://d306pr3pise04h.cloudfront.net/docs/news_events%2F8.1%2FGC_Summit_Report_07.pdf (Accessed: 20.08.2022) (2007). In more recent literature, it is often referred to as the theory of green human resource management, which indicates leveraging human talent for the succession of sustainable goals. Parts of leveraging individuals can be training and development on the one hand and creating responsibility on the other hand. 69Gupta, H. Assessing organizations performance on the basis of GHRM practices using BWM and Fuzzy TOPSIS. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, Vol. 226, 201-216 (2018). To serve the main purpose of employee training, several topics like concepts, principles and practices can be introduced to the listeners that help them to eventually deal with the use of new digital technologies or the correct waste disposal for example. 70Klein, N. et al. Factors and Strategies for Circularity Implementation in the Public Sector: An Organisational Change Management Approach for Sustainability. Corporate Social-Responsibility and Environmental Management, Vol. 29 (3), 509–523 (2021). Research has shown that the sustainability management tool of employee training is one of the most implemented ones by companies and has a relatively high awareness among them. 71Johnson, M. P. Sustainability Management and Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: Managers’ Awareness and Implementation of Innovative Tools. Corporate Social-Responsibility and Environmental Management, Vol. 22 (5), 271–285 (2015). Its execution could result in several potential benefits, such as the main benefit, namely the change of attitudes. Additionally, it positively influences employees’ skills and knowledge, their awareness, and their motivation to promote sustainability. On an organizational level, it contributes to the implementation of an environmental management system. 72Klein, N. et al. Factors and Strategies for Circularity Implementation in the Public Sector: An Organisational Change Management Approach for Sustainability. Corporate Social-Responsibility and Environmental Management, Vol. 29 (3), 509–523 (2021). In contrast, several disadvantages can be derived from the literature regarding sustainability training as it is questioned, whether training can deal with employees’ cynical postures toward the importance and relevance of topics like sustainability. It is argued that the effectiveness of training sessions must be priorly assessed before it is carried out. Another disadvantage might be, that re-training can occur if employees switch their job coming from a more polluted industry and apply at a sustainable organization. In fact, management must release those employees more often for training purposes, which could result in additional costs as well as time issues. 73Renwick, D. W.S. et al. Green Human Resource Management: A Review and Research Agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews: IJMR, Vol. 15 (1), 1–14 (2013).

3.3.3 Sustainability Balanced Scorecard

Another tool that now focuses on sustainability is the Sustainability Balanced Scorecard (SBSC). The basis of the SBSC is the classic Balanced Scorecard (see figure 5) according to Kaplan and Norton, an approach to performance measurement for companies from 1992. 74Kaplan R.S. & Norton, D.P. The Balanced Scorecard – Measures that Drive Performance. Havard Business Review (January-February), 71-79 (1992). With help of a BSC, a company can make clear in a top-down process which goals are particularly important to it and at the same time illustrate associated key figures. Since it is often the case that several objectives are relevant at the same time, the various objectives are divided into four perspectives on the scorecard in order to maintain an overview. The second core element of the BSC is the linking of the goals with key figures and indicators. 75Hansen E.G. & Schaltegger, S. The Sustainability Balanced Scorecard: A systematic Review of Architectures, Journal of business ethics, Vol. 133 (2), 193-221 (2016). Kaplan and Norton decided on a selection of perspectives that, in their view, made it possible to achieve a balance between goals and metrics. This also explains the name of the model: Balanced Scorecard. The first perspective is the financial perspective, which primarily includes the usual financial goals and metrics such as return on investment, profit, and sales. Number two is the customer perspective, which should represent customer opinions about the company. Factors here are things like customer satisfaction, complaints or the rate of customers who buy more than once. The quality of internal processes, for example, measurable by time, costs or rates of rework, is represented by the process perspective. Finally, Kaplan and Norton name the learning and development perspective, which is intended to show the extent to which a company is prepared for future developments. Indicators here are, for example, innovations, employee satisfaction or the image of the company. 76Friedag H.R. / Schmidt, W. Balanced Scorecard ( 4th edn, Haufe Verlag, 2011). The aim of the BSC is to visualize whether the previous actions of the company were successful and whether this will also be the case in the future. In order to do this as meaningfully as possible, a distinction is made between lagging indicators and leading indicators. 77Barthelemy F. et. al. Balanced Scorecard (Vieweg+Teubner Verlag, 2011). Late indicators are characterized by the fact that some time must pass before the success of an action can be evaluated. This means that only successes or failures that lie in the past are depicted. A good example of this is the profit total of a company. Early indicators, on the other hand, can show very soon after the action whether a measure has a positive or negative effect. In some cases, leading indicators are also able to anticipate developments. For example, an increasing number of complaints from customers indicates that overall satisfaction is also declining. 78Hahn, T. & Wagner, M. Sustainability Balanced Scorecard. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Tobias-Hahn-7/publication/242318368_Sustainability_Balanced_Scorecard/links/00b49533d95e2cfe26000000/Sustainability-Balanced-Scorecard.pdf (2001). Companies should pursue the goal of constantly improving their performance in all of the four perspectives mentioned. The BSC should help to show in a clear and comprehensible way whether decisions or measures taken contribute to the achievement of this goal.

However, the perspectives proposed by Kaplan and Norton are not rigid and can be adapted or expanded depending on the type and strategy of the company. 80Hahn, T. & Wagner, M. Sustainability Balanced Scorecard. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Tobias-Hahn-7/publication/242318368_Sustainability_Balanced_Scorecard/links/00b49533d95e2cfe26000000/Sustainability-Balanced-Scorecard.pdf (2001). Several economists took advantage of this and gradually established a further development: the SBSC. This is intended to make it easier to embed the three pillars of sustainability (economic, ecological, social) in successful strategy implementation. The aim is for the company to improve in terms of all three pillars and thus make a strong contribution to the general development of sustainability. 81Figge, F. & Hahn, T. & Schaltegger, S. & Wagner, M. Sustainability Balanced Scoercard: Wertorientiertes Nachhaltigkeitsmanagement mit der Balanced Scorecard. Lüneburg: Center for Sustainability Management (2001). This concept is particularly relevant because the BSC makes it possible to include non-monetary aspects, such as environmental and social concerns, in the evaluation of the company’s success. 82Bieker, T. & Gminder, C.-U. & Hahn, T. & Wagner, M. “Unternehmerische Nachhaltigkeit umsetzen: Welchen Beitrag kann die Balanced Scorecard dazu leisten?”, Ökologisches Wirtschaften (2001). In order to integrate environmental and social aspects into the classic BSC, three different approaches are proposed in the literature. One approach is to integrate the desired new issues into the four existing perspectives. Another option is to leave the four perspectives as they are and add a fifth perspective, which is then used to measure environmental and social measures. In this case, Figure 1 would have a fifth “Environment & Social” evaluation matrix. The third and probably most radical alternative would be to create a completely new scorecard that is no longer primarily oriented to economic goals, but to sustainability goals. 83Figge, F. & Hahn, T. & Schaltegger, S. & Wagner, M. The Sustainability Balanced Scorecard – linking sustainability management to business strategy, Business strategy and the environment, Vol. 11 (5), 269-284 (2002).

The SBSC can help to successfully implement a change management process to increase sustainability. Since the perspectives are not rigid and can be adapted or expanded again and again, the tool can be used variably and can react to new circumstances during the change process without great difficulty. Furthermore, the BSC makes it possible to evaluate the effect of measures or actions in different stages and from different perspectives and to compare their success with other measures. In summary, it can be said that the SBSC is well suited to measure the actions during a change and to communicate the results externally or from top to bottom. Successes become more tangible and can increase acceptance and motivation for change. 84Hahn, T. & Wagner, M. Sustainabilty Balanced Scorecard. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Tobias-Hahn-7/publication/242318368_Sustainability_Balanced_Scorecard/links/00b49533d95e2cfe26000000/Sustainability-Balanced-Scorecard.pdf (2001). However, it is important to keep in mind that the BSC tends to only evaluate actions and can reveal certain relationships. It cannot, therefore, contribute to greater sustainability on its own, nor can it manage a change process. Another disadvantage could be that the BSC, which is largely based on key figures, reaches its limits when it comes to the topic of sustainability, which consists of countless factors and interrelationships. 85Hahn, T. & Figge, F. Why Architecture Does Not Matter: On the Fallacy of Sustainability Balanced Scorecards, Journal of Business Ethics (2018) 150, 919-935 (2016).

3.3.4 Circular Economy Assessment Framework

As a final example of tools that can help implement a change process, a framework for Circular Economy (CE) will be presented. This framework was published in 2021 by Hinrika Droege and others. The goal of the authors was to create a CE assessment framework that, unlike existing ones, can be applied primarily to the public sector. This tool is therefore quite specific, but because of its timeliness and innovation, it should be acknowledged.

CE is the move away from the one-time use of a resource to sustainable development with aspects such as alternative recovery, recycling or the recovery of materials in production/distribution and consumption processes. The goals of this process are sustainability, environmental protection, financial prosperity and social justice over many generations. 86Kirchherr, J. & Reike, D., & Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resources, Conservation & Recycling (Volume 127), 221-232 (2017). Even though CE has really boomed in the literature in recent years 87Daddi, T., Cegali, D., Bianchi, G., & Dutra de Barcellos, M. Paradoxical tensions and corporate sustainability: A focus on circular economy business cases. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management., Vol. 26 (4), 770– 780 (2019)., authors still disagree on what exactly a CE concept should include. However, there is consensus that CE plays out on three levels. First, at the macro level of policies and regulations; second, at the meso level of industrial networks; and third, at the micro level of organizations, products and materials. 88Kirchherr, J. & Reike, D., & Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resources, Conservation & Recycling (Volume 127), 221-232 (2017). Looking at an organization, we distinguish between resources that flow in, resources that flow out, and some resources that remain in the structure over a period of time. 89Potting, J. & Hekkert, M. & Worrell, E. & Hanemaaijer, A. Circular economy: Measuring innovation in the product chain. PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. https://www.pbl.nl/sites/default/files/downloads/pbl-2016-circular-economy-measuring-innovation-in-product-chains-2544.pdf (2017). Following the goal of sustainability, it is crucial to evaluate those resources, practices and strategies in terms of their contribution to the Circular Economy. In order to make this evaluation process measurable and tangible, CE indicators must be determined. 90Parchomenko, A. & Nelen, D. & Gillabel, J., & Rechberger, H. Measuring the circular economy—A multiple correspondence analysis of 63 metrics. Journal of Cleaner Production, p. 210 (2019). Since the public sector, to which the tool refers, has a key role in the general CE implementation 91Khan, O., Daddi, T., & Iraldo, F. The role of dynamic capabilities in circular economy implementation and performance of companies. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 3018–3033 (2020)., it is necessary to define it once. The OECD describes an organization as belonging to the public sector if it is under government control and develops public goods or services. 92Droege, H. & Raggi, A. & Ramos, T.B. Co-development of a framework for circular economy assessment in organisations: Learnings from the public sector, Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag. 1715-1729 (2021). In the implementation of a CE process, there are several CE principles, the presentation of which, however, would go beyond the scope here. Ideally, however, the specific CE indicators should provide information on how well the organization applies the selected CE principles. 93Droege, H. & Raggi, A. & Ramos, T.B. Co-development of a framework for circular economy assessment in organisations: Learnings from the public sector, Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag. 1715-1729 (2021).

Due to a lack of knowledge and literature about CE assessments in the public sector, the tool is significantly based on a single case study of a Portuguese CE coordination group (PCECG). Three criteria were always considered in the creation of the framework: CE competence, assessment competence, and representation of different public sector organizations. 94Droege, H. & Raggi, A. & Ramos, T.B. Co-development of a framework for circular economy assessment in organisations: Learnings from the public sector, Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag. 1715-1729 (2021). As a result of literature research, field study, and several workshops with research stakeholders, the framework for identifying CE elements should consist of resources, processes and procedures, and employee-related activities. The result was a framework into which each organization could add its specific elements. At the same time, however, the goal was to illustrate which of the elements apply across different public sector organizations. Elements that are very specific and only relevant for individual organizations were grouped under “example” and can be concretized as needed during actual implementation. In order to meet the requirement of transparency, CE elements are not only named, but also substantiated by examples in the framework. There was also consensus that the framework and the indicators it contains should be kept simple and that the evaluation should be as transparent and comprehensible as possible. 95Droege, H. & Raggi, A. & Ramos, T.B. Co-development of a framework for circular economy assessment in organisations: Learnings from the public sector, Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag. 1715-1729 (2021). In the final version, the framework consists firstly of a table that names an example, an R principle (e.g., Reduce, Refuse, Rethink), a BSI principle, a goal, indicators, and the priority of the element, in addition to the CE element under consideration. For the water CE element, for example, it looks as follows: CE element: Water, Example: drinking water/water used for toilets, R principle: reduce, BSI principle: Value optimization, Target: reduce freshwater usage, Indicator: m3 of fresh water used, Priority: moderate. In addition to resources, operations and processes as well as social and employee-related activities are also considered CE elements. 96Droege, H. & Raggi, A. & Ramos, T.B. Co-development of a framework for circular economy assessment in organisations: Learnings from the public sector, Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag. 1715-1729 (2021). The developed framework differs from previous CE frameworks, which were not tailored to the public sector, in three main points. (1) While previous CE frameworks focused on environmental and economic dimensions of sustainability, the presented tool follows a CE perspective that additionally includes social and institutional dimensions of sustainability. (2) The tool developed is tailored to a sector and its specific needs and circumstances. (3) Previous frameworks are too multi-layered and thus lose their informative character due to their complexity. 97Droege, H. & Raggi, A. & Ramos, T.B. Co-development of a framework for circular economy assessment in organisations: Learnings from the public sector, Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag. 1715-1729 (2021). Another plus point of the framework is the involvement of stakeholders in the development process, as this means that the needs and requirements of specific organizations are incorporated from the outset. 98Sierra-García, L. & Zorio-Grima, A. & García-Benau, M. A. Stakeholder engagement, corporate social responsibility and integrated reporting: An exploratory study. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 286–304 (2013). Since empirical data proves this, it is advisable to have specific stakeholders participate in the creation process of other novel frameworks in the future. However, it is important to note that the simplified design of the framework also has its drawbacks. In many cases, for example, it is not possible to represent the sometimes-complicated relationships between several CE elements with only one target per indicator. But if you start the change process with the simple framework, you can gradually analyze experiences and lessons learned and expand the framework. Another disadvantage is that the framework only evaluates the CE process, whether an improvement of the CE elements actually leads to more sustainability is not necessarily given. 99Moraga, G. et. al. Circular economy indicators: What do they measure?Resources, Conservation & Recycling, 452–461 (2019). For example, a good CE rating can be achieved because a resource named in the framework is saved. However, if this resource is replaced by another that is similar or even more environmentally damaging, the CE rating is better, but the behavior is not more sustainable. 100Droege, H. & Raggi, A. & Ramos, T.B. Co-development of a framework for circular economy assessment in organisations: Learnings from the public sector, Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag. 1715-1729 (2021).

In summary, the framework can be evaluated similarly to the SBSC in terms of implementing a change process. An appropriate assessment framework can clearly drive the change process toward the Circular Economy. The progress of the organization is evaluated and can be communicated transparently and clearly to the outside world, which, as already mentioned, can increase the motivation of those involved. 101Droege, H. & Raggi, A. & Ramos, T.B. Co-development of a framework for circular economy assessment in organisations: Learnings from the public sector, Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag. 1715-1729 (2021). However, the limitations of the framework’s informative value cannot be dismissed out of hand. Since it is only based on a case study, there is little literature and research on the subject and the concept is still in its infancy, one must observe the development of the coming years before making a final judgment. The fact that the framework is tailored to the public sector should not be seen as negative. Especially in terms of the methodology used to create it, the findings can be applied to many other sectors as well.

3.4 Best practices

Best practices resulting from the implementation process of sustainability generally address different kinds of levels and should ideally enhance the change enablers, explained in chapter 3.1. Additionally, the presented tools in the previous chapter should profit from best practices, especially in terms of their execution. To begin with, the level of content as elaborated by Anderson & Ackerman (2001), there are several best practices focusing on the strategy of the change. It is useful to build strategies, policies and similar around sustainability practices. Those could potentially deal with specific sustainable targets or give valuable guidance to execute certain procedures in a sustainable way. 102Dahl Sönnichsen, S. & Clement, J. Review of green and sustainable public procurement: Towards circular public procurement. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 245 (118901), 1–18 (2020). A further best practice covering several change enablers and presented tools, is the installation of sustainability change agents on employee- and management levels. 103Mendoza, J. M. F., Gallego-Schmid, A., & Azapagic, A. A methodological framework for the implementation of circular economy thinking in higher education institutions: Towards sustainable campus management. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 226, 831–844 (2019). This innovative approach highlights an individual view on leadership and commitment and defines change agents as people, who use their own competencies and skills to promote organizational culture. Therefore, it considers the importance of individual leadership by employees and managers which is crucial for the change process. 104Davis, M., & Coan, P. Organizational change. In J. L. Robertson & J. Barling (Eds.), The psychology of green organizations, Vol. 53 (9), 1689–1699 (2019). Two additional best practices dealing with the strategic component are finally the creation of a focal point and group works on sustainable topics. To put the responsibility on a focal point, arguably emerges inter-organizational and cross-departmental collaboration, whereas work groups additionally have a significant impact on developing realistic sustainable strategies. 105Klein, N. et al. Factors and Strategies for Circularity Implementation in the Public Sector: An Organisational Change Management Approach for Sustainability. Corporate Social-Responsibility and Environmental Management, Vol. 29 (3), 509–523 (2021).

Regarding the level of people with their knowledge and skills (see figure 4), the hire of sustainability experts is a reasonable practice to gain people with the required competencies. Those experts can be explicitly brought in to disseminate the idea of sustainability. 106Klein, N. et al. Factors and Strategies for Circularity Implementation in the Public Sector: An Organisational Change Management Approach for Sustainability. Corporate Social-Responsibility and Environmental Management, Vol. 29 (3), 509–523 (2021). Moreover, to go even beyond the idea of hiring experts, the establishment of departments dedicated to sustainability could concretize the goal of organizational sustainability and transfer the mission to the respective employees in charge. 107Figueira, I. et al. Sustainability policies and practices in public sector organisations: The case of the Portuguese central public administration. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 202, 616–630 (2018). The tool of employee training presented previously can also be defined as a best practice because sustainability training sessions enhance the enabler of employees’ knowledge and skills. 108Renwick, D. W.S. et al. Green Human Resource Management: A Review and Research Agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews: IJMR, Vol. 15 (1), 1–14 (2013). Further practices, that should be just shortly addressed are the potential use of guidelines, signs or instructions which deal with sustainable topics at the company and the creation of awards in cases of proper realization. 109Klein, N. et al. Factors and Strategies for Circularity Implementation in the Public Sector: An Organisational Change Management Approach for Sustainability. Corporate Social-Responsibility and Environmental Management, Vol. 29 (3), 509–523 (2021).

As pointed out in chapter 3.2.2, communication and assessment are important parts of the theoretical framework of an implementation process of change. A practice, that promotes both is the installation of an assessment system, that enables the measurement of sustainable performance. 110Droege, H. & Raggi, A. & Ramos, T.B. Co-development of a framework for circular economy assessment in organisations: Learnings from the public sector, Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag. 1715-1729 (2021). Two of those potential systems were already presented in chapter 3.3, namely the SBSC and the CE assessment framework by Droege et al. (2021). In addition, these frameworks could be then complemented by internal audits or diagnostics, dealing with energy efficiencies for example. 111Klein, N. et al. Factors and Strategies for Circularity Implementation in the Public Sector: An Organisational Change Management Approach for Sustainability. Corporate Social-Responsibility and Environmental Management, Vol. 29 (3), 509–523 (2021). To continue with the area of communication, several practices like digital questionnaires, conferences or similar events have emerged as suitable options to spread and update employees’ as well as stakeholders’ knowledge. 112Coutinho, V. et al. Employee-driven sustainability performance assessment in public organisations. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, Vol. 25 (1), 29–46 (2018). To conclude the chapter, it is generally difficult to name a best practice.

4 Drivers and barriers

Studies have shown that the failure of change processes is not a usual phenomenon at all. 113Lauer, T. Change management: fundamentals and success factors. (Springer, 2021). A failure rate of change processes of 75% is considered standard internationally. 114Eaton, M. Why change programmes fail. Human Resource Management International Digest, Vol. 18 (5), (2010). As mentioned in previous sections, for successful change management implementation and associated successful change, it is necessary to identify and overcome barriers. This section will look at what barriers are usually responsible for the mentioned failure rate in relation to sustainable change management and how there can be a better chance to overcome these barriers. In the context of overcoming barriers, some drivers of change management are also of great importance in relation to driving and supporting sustainable change processes. These drivers will be examined in more detail after the barriers have been presented first. Since change management is more concerned with how companies manage internal change, we will also have a more detailed look at internal barriers and drivers than at external factors. The external barriers and drivers are more limited to regulations and developments that make a change necessary and justify it in the first place.

4.1 Barriers

According to Post and Altma (1994), a distinction can be made between two types of barriers: industry and organizational barriers. Industry barriers reflect the “special and unique features of the business activity in which the firm engages” 115Post, J., Altma, B. Managing the Environmental Change Process: Barriers and Opportunities. Journal of organizational change management, Vol. 7 (4), 64-81 (1994).. Those barriers are therefore very industry-specific and differ a lot depending on the industry. This does not apply to organizational barriers. Organizational barriers complicate a firm’s dealing with any form of change, including environmental change. 116Post, J., Altma, B. Managing the Environmental Change Process: Barriers and Opportunities. Journal of organizational change management, Vol. 7 (4), 64-81 (1994). This section will primarily deal with this type of barrier.

The main barrier leading to the high failure rate of change processes is resistance from employees. In addition to the predictable and logical resistance due to, for example, salary cuts or loss of power of employees, there is also resistance for which there is not always a clear reason. These resistances are even more important for managing changes because they are hard to predict and manage. The origin of that unreasonable resistance is usually found in psychological reasons like, for example, the general tendency of people to build resistance against changes that are associated with a loss of freedom. 117Lauer, T. Change management: fundamentals and success factors. (Springer, 2021). In this context employees could associate sustainable changes with a loss of freedom due to more restrictions and regulations. Whereas previously employees might have been guided only by economic goals, now environmental goals are added, which limits their freedom to shape their work and could therefore lead to resistance.

These resistances can be reinforced by different reasons that make change more difficult. Those reasons can also be considered as barriers and can be grouped into personal factors for resistance, organizational factors for resistance and factors that are specific to the change itself. 118Rosenberg, S., Mosca, J. Breaking Down the Barriers to Organizational Change. International Journal of Management & Information Systems, Vol. 15 (3), 139-146 (2011). For personal factors for resistance, we could think about bad employee attitudes. For example, if an employee is unwilling to commit to change, does not give sustainability a high priority and acts in an unmotivated manner, it slows down the success of the change. It would also be possible that the employee is just not capable of the changes because of a lack of skills or knowledge. 119Post, J., Altma, B. Managing the Environmental Change Process: Barriers and Opportunities. Journal of organizational change management, Vol. 7 (4), 64-81 (1994). In addition, the fear of failure, the fear of the unknown and the disruption of routine can also be mentioned as personal factors for resistance. 120Rosenberg, S., Mosca, J. Breaking Down the Barriers to Organizational Change. International Journal of Management & Information Systems, Vol. 15 (3), 139-146 (2011). An example of an organizational factor for resistance is the bad quality of communication. 121Post, J., Altma, B. Managing the Environmental Change Process: Barriers and Opportunities. Journal of organizational change management, Vol. 7 (4), 64-81 (1994). It can be very important that employees understand the reason for the change and the benefit that can result from the successful change. If this is not the case, the employees most likely won’t support the change process. The same can result from inadequate top management leadership. 122Post, J., Altma, B. Managing the Environmental Change Process: Barriers and Opportunities. Journal of organizational change management, Vol. 7 (4), 64-81 (1994). Other organizational factors are a lack of trust between management and employees, a lack of participation of the employees, internal conflicts for resources and a lack of consequences for inadequate or bad performance. As factors that are specific to the change itself, the content of the change and poor implementation planning can be mentioned. 123Rosenberg, S., Mosca, J. Breaking Down the Barriers to Organizational Change. International Journal of Management & Information Systems, Vol. 15 (3), 139-146 (2011).

Another potential barrier, but also a potential driver, is the pressure of other stakeholders, for example, the shareholders. 124Valero-Gil, J., Rivera-Torres, P., Garcés-Ayerbe, C. How Is Environmental Proactivity Accomplished? Drivers and Barriers in Firms’ Pro-Environmental Change Process. Sustainability, Vol.9 (8), 1327 (2017). Shareholders are often very profit-oriented, which could be inconsistent with sustainability. This way, the stakeholder pressure could be a barrier to sustainable change.

Most of the mentioned barriers can be understood as reasons for resistance as well, which is the main barrier to change processes. The drivers of sustainable change management, which will be presented below, can help to overcome these resistances, or even prevent them from arising.

4.2 Drivers

Prior literature defines the term “change drivers” in two different ways. The first definition defines change drivers as drivers that facilitate the implementation of change in an organization and the individual adoption of change initiatives. In this chapter, we will deal with the drivers defined in this way. The other definition of change drivers focuses on drivers of the necessity for change. 125Whelan-Berry, K., Somerville, K. Linking Change Drivers and the Organizational Change Process: A Review and Synthesis. Journal of change management, Vol. 10 (2), 175-193 (2010). In terms of sustainability, those drivers are for example the increasing natural disasters in a macroeconomic view, but also political regulations that companies must deal with. These drivers can be understood as external drivers.

One of the main internal drivers for change is that the change vision is accepted by employees and other stakeholders. This means, that the employees and other stakeholders should be considered that the change vision is positive for the organization and also for themselves. 126Whelan-Berry, K., Somerville, K. Linking Change Drivers and the Organizational Change Process: A Review and Synthesis. Journal of change management, Vol. 10 (2), 175-193 (2010). The change visions should motivate employees and lead to lower resistance by giving a basic orientation and a realistic picture of the future. 127Lauer, T. Change management: fundamentals and success factors. (Springer, 2021). Prior research has shown that this driver has a positive impact on individual employee change and widespread change implementation and therefore is essential for successful organizational change. 128Brenner, M. It’s all about people: change management’s greatest lever. Business Strategy Series, Vol. 9 (3), 132-137 (2008).

Another driver of sustainable change management is good leadership. The change-related actions of leaders are critical to the successful implementation of changes and can send important signals to employees. In this way, employees can be considered the importance of the change and their understanding of the change vision can be strengthened. 129Whelan-Berry, K., Somerville, K. Linking Change Drivers and the Organizational Change Process: A Review and Synthesis. Journal of change management, Vol. 10 (2), 175-193 (2010). An important leadership task that can drive the change process is the whole planning of the process. Setting a clear timeframe and addressing the critical factors affecting the change’s success can increase the success of the process. 130Chrusciel, D., Field, D. Success factors in dealing with a significant change in an organization. Business Process Management Journal, Vol.12 (4), 503-516 (2006). Another benefit of good planning and analysis is that the organization can always identify the progress of the change process to see how far they are from reaching their goals. 131Al-Haddad, S. & Kotnour, T. Integrating the Organizational Change Literature: a Model for Successful Change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, Vol. 28 (2), 234–262 (2015). Good leadership through change is also characterized by certain human resource practices. Here, for example, the performance evaluation and reward system can be aligned with the intended target. 132Whelan-Berry, K., Somerville, K. Linking Change Drivers and the Organizational Change Process: A Review and Synthesis. Journal of change management, Vol. 10 (2), 175-193 (2010). To drive sustainable change, it would be conceivable here to use ecological indicators as performance appraisal criteria in addition to economic indicators.

A hereby related driver of sustainable change management can be good communication. Since the main task of good leadership is good communication, this change driver is contained in almost all other change drivers. 133Lauer, T. Change management: fundamentals and success factors. (Springer, 2021). Good communication can remove any misunderstandings and obstacles about the intended change and facilitate the understanding and engagement of the employees. 134Whelan-Berry, K., Somerville, K. Linking Change Drivers and the Organizational Change Process: A Review and Synthesis. Journal of change management, Vol. 10 (2), 175-193 (2010). In this context it’s especially important to make clear why the change is necessary and to communicate the change vision and the related strategies as clearly as possible. 135Nadler, D., Tushman, M. Beyond the charismatic leader: Leadership and organizational change. Calif Manage Rev. Vol. 32 (2), 77-97 (1990). As mentioned before, communication can also be a barrier and a potential failure factor. The choice of communication can therefore determine whether misunderstandings and barriers occur or whether the message (importance, vision, goals etc.) is clearly communicated and understood by employees so that the communication works as a success factor. 136Lauer, T. Change management: fundamentals and success factors. (Springer, 2021).

Another aspect that can positively influence the success of a change process is change-related training. 137Whelan-Berry, K., Somerville, K. Linking Change Drivers and the Organizational Change Process: A Review and Synthesis. Journal of change management, Vol. 10 (2), 175-193 (2010). Prior investigations show that training can improve change-related knowledge, skills and behaviors 138Schneider, B., Gunnarson, S., Niley-Jolly, K. Creating the climate and culture of success. Organizational Dynamics, Vol.23 (1), 17-29 (1994). and can therefore lead to more practiced handling of change initiatives of the employees. The acquired knowledge, in turn, can also act as a driver for innovations and new technologies, which are very effective and important, especially regarding the sustainable change. 139Dey, A. Change Management Drivers: Entrepreneurship and Knowledge Management. South Asian Journal of Business and Management Cases, Vol. 6 (1), vii-ix (2017). In addition, the knowledge can lead to a better understanding of the change necessary. The employees should be sensitized and educated in relation to the topic of sustainability so that they can understand the importance of sustainable change.

Given literature about this subject also shows that involving the employees in change-related tasks, for example in the implementation, can lead to a deeper understanding of the change initiative and to more commitment from the employees. 140Whelan-Berry, K., Somerville, K. Linking Change Drivers and the Organizational Change Process: A Review and Synthesis. Journal of change management, Vol. 10 (2), 175-193 (2010). In addition, the employees can get a better understanding of what the change will mean to their job, role or function. 141Whelan-Berry, K., Somerville, K. Linking Change Drivers and the Organizational Change Process: A Review and Synthesis. Journal of change management, Vol. 10 (2), 175-193 (2010). These mentioned consequences of more participation of those affected by the change, can increase their motivation and decrease their resistance to the change. 142Lauer, T. Change management: fundamentals and success factors. (Springer, 2021). Besides the direct involvement of employees in tasks related to the change initiative, an important method of participation can also be employee surveys. Through employee surveys, the management can get valuable information about the priorities and opinions of the employees, which can be difficult to get any other way. 143Roberts, D., Levine, E. Employee Surveys: A Powerful Driver for Positive Organizational Change. Employment Relations Today, Vol. 40 (4), 39-45 (2014). In this way, the management can also figure out where the employees possibly identify barriers and how the employee is evaluating the specific change initiative. In relation to sustainability, the employees might have useful information on how to work more sustainably, which the top management might not even have. Thus, an information gap between management and employees could be closed by using employee surveys.

As we have seen, there are a lot of potential drivers that can drive a successful sustainable change within organizations. Most of the mentioned drivers have in common, that they try to reduce the impact of resistance, which is the main barrier to change processes. By focusing on all the mentioned change drivers, the barriers to change can be overcome to maximize the probability of a successful change implementation that leads to the intended condition after the change.

References

- 1Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018).

- 2Lauer, T. Change Management: Grundlagen und Erfolgsfaktoren. (Springer Gabler, 2019).

- 3Ha, H. Change Management for Sustainability. (Business Expert Press, 2014).

- 4Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018).

- 5Ha, H. Change Management for Sustainability. (Business Expert Press, 2014).

- 6Große Ophoff, M. Herausforderung Klimaschutz: Warum wir keine Zeit mehr haben. in Unterwegs zur neuen Mobilität: Perspektiven für Verkehr, Umwelt und Arbeit (Flore, M., Kröcher, U. & Czycholl, C.) 19-31 (oekom Verlag, 2021).

- 7Fazel, L. Akzeptanz von Elektromobilität: Entwicklung und Validierung eines Modells unter Berücksichtigung der Nutzungsform des Carsharing. (Springer Fachmedien, 2014).

- 8Flore, M., Kröcher, U., & Czycholl, C. Unterwegs zur neuen Mobilität: Perspektiven für Verkehr, Umwelt und Arbeit. (oekom Verlag, 2021).

- 9Fazel, L. Akzeptanz von Elektromobilität: Entwicklung und Validierung eines Modells unter Berücksichtigung der Nutzungsform des Carsharing. (Springer Fachmedien, 2014).

- 10Cesnuityte, V., Klimczuk, A., Miguel, C., & Avram, G. The Sharing Economy in Europe: Developments, Practices, and Contradictions. (Palgrave Macmillan (Springer Nature Switzerland AG), 2022).

- 11Fitte, C., Berkemeier, L., Teuteberg, F., & Thomas, O. Elektromobilität in ländlichen Regionen. in Smart Cities/Smart Regions – Technische, wirtschaftliche und gesellschaftliche Innovationen (Gómez, J. M., Solsbach, A., Klenke, T. & Wohlgemuth, V.) 37-52 (Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH, 2019).

- 12Ha, H. Change Management for Sustainability. (Business Expert Press, 2014).

- 13Ha, H. Change Management for Sustainability. (Business Expert Press, 2014).

- 14Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018).

- 15Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018).

- 16Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018).

- 17Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018).

- 18Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018).

- 19Ha, H. Change Management for Sustainability. (Business Expert Press, 2014).

- 20Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018).

- 21Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018).

- 22Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018).

- 23Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018).

- 24Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018).

- 25Ha, H. Change Management for Sustainability. (Business Expert Press, 2014).

- 26Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018).

- 27Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018).

- 28Ha, H. Change Management for Sustainability. (Business Expert Press, 2014).

- 29Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018).

- 30Rasche, C. & Rehder, S. A. Change Management. (Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2018).

- 31Ha, H. Change Management for Sustainability. (Business Expert Press, 2014).

- 32Maiti, M. What is Change Management Educationleaves https://educationleaves.com/change-management/ (2021).

- 33Al-Haddad, S. & Kotnour, T. Integrating the Organizational Change Literature: a Model for Successful Change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, Vol. 28 (2), 234–262 (2015).

- 34Oldham, J. Achieving large system change in health care. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 301 (9), 965-966 (2009).

- 35Margolis, P. A. et al. Designing a Large-Scale Multilevel Improvement Initiative: The Improving Performance in Practice Program. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, Vol. 30 (3), 187–196 (2010).

- 36Stock, Byron A. Leading Small-Scale Change. Training & Development (Alexandria, Va.), Vol. 47 (2), 45 (1993).

- 37Bennett, W.L. & Segerberg, A. The logic of connective action. Information, Communication & Society, Vol. 15 (5), 739-768 (2012).