Authors: Leonie Huesmann, Lena Huhne, Janika Icken, Levin Mersch

Last updated: December 19, 2022

1 Definition and relevance

In recent decades, the interest in the development of environmental security has been rise due to the thematic of global warming 1Kritika, S. Kaushal und Abhishek, „Eco-labeling: The Influence of Eco-labeld Products on Consumer Buying Behavior,“ Just Agriculture, pp. 1-5, October 2021.. As a consequence of this, the awareness of consumers regarding the environment has changed. Consumers have started to rethink their consumption behaviour and reflect their purchasing decisions ecologically. Furthermore, the demand for “green” products has been growing 2A. De Chiara, „Eco-labeld Products: Trends or Tool for Sustainability Strategies,“ Journal of Business Ethics, pp. 161-172, 2016. and the requirement for sustainable business practices by companies has emerged 3Kritika, S. Kaushal und Abhishek, „Eco-labeling: The Influence of Eco-labeld Products on Consumer Buying Behavior,“ Just Agriculture, pp. 1-5, October 2021..

Consumers have a positive attitude towards socially responsible companies 4J. Gosselt, T. van Rompay und L. Haske, „Won’t Get Fooled Again: The Effects of Internal and External CSR ECO-Labeling,“ Journal of Business Ethics, pp. 413-424, 2019.. Firms that are aware of their corporate social responsibility (hereinafter: CSR) and communicate their attitudes to costumers, benefit from positive impact on their brand image. As an example, companies with social commitment profit from an increasing financial improvement and employee engagement. The benefits that companies gain from their social responsibility explain the increasing interest of companies in eco-labels 5A. De Chiara, „Eco-labeld Products: Trends or Tool for Sustainability Strategies,“ Journal of Business Ethics, pp. 161-172, 2016.. In addition, the growing environmental interest of the population lead to the implementation of eco-labels 6M. Salman, „Eco Labels: Tools of Green Marketing,“ International Research Journal of Management Sociology & Humanity, Bd. 5, pp. 16-23, 2016..

Eco-labels are labels that identify the environmental performance of products or services within certain categories 7R. Gertz, „Eco-lanelling – a case for deregulation,“ Law, Probability and Risk, pp. 127-141, 2005.. They are awarded as a symbol or a sign by objective and impartial third-party organizations to products or services that are proven to be beneficial to the environment 8M. Salman, „Eco Labels: Tools of Green Marketing,“ International Research Journal of Management Sociology & Humanity, Bd. 5, pp. 16-23, 2016.. Moreover, eco-labels are considered as an information-gathering tool and are therefore often seen as instruments of environmental policy 9M. Saal, Eco-Labelling und Länderunterschiede – Voraussetzungen für ein effektives Eco-Label-System, Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH, 2017.. They are intended to reduce the information asymmetry that arises between producers and consumers by enabling manufacturers to provide reliable information about the environmental attributes of their products, illustrating that their product is better than others 10M. Delmas und L. Grant, „Eco Labeling Strategies and Price-Premium: the Wine Industry Puzzle,“ Business & Society, Bd. 1, pp. 161-172, 2014..

Eco-labelling is a voluntary method that aims to label and promote products that stand out from other products due to their environmental impact 11R. Gertz, „Eco-lanelling – a case for deregulation,“ Law, Probability and Risk, pp. 127-141, 2005.. From a consumer perspective, eco-labels are primarily intended to provide consumers with extensive information to increase environmental awareness and assist them in making conscious purchasing decisions about environmentally friendly products. From a company perspective, eco-labels are intended to encourage firms to make environmental improvements to their own products 12F. Iraldo, R. Griesshammer und W. Kahlenborn, „The future of ecolabels,“ The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, Bd. 5, pp. 833-839, 2020..

The fact that eco-labels inform consumers and inspire companies to produce sustainable prod-ucts is illustrated by Lidl’s product labelling in the form of the “Haltungskompass”. Lidl’s “Hal-tungskompass” clarifies the functions of environmental labels for companies and consumers. Moreover, the discounter advocates the responsibility of animal products and more animal welfare. This, as well as changing consumer habits and trends of lower meat consumption, led the retailer to label its own animal products with the Lidl-Haltungskompass throughout Germany in February 2019. The Lidl-Haltungskompass is an easy-to-understand four-step model that illustrates different ways animals are kept in order to provide more transparency in animal husbandry. Many companies have followed Lidl’s label and introduced their own husbandry labels, that have now been standardized as “Haltungsform”. The different categories of the husbandry are shown in the following figure: 13Lidl Dienstleistung GmbH & Co. KG, „Verantwortung für tierische Produkte,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://unternehmen.lidl.de/verantwortung/handlungsfeld-sortiment/food-sortiment/tierische-produkte. [Zugriff am 28.06.2022]. , 14Lidl Dienstleistung GmbH & Co. KG, „Rund 50 Prozent des Frischfleischsortiments auf Stufe 2 “Stallhaltung plus”,“ [Online]. Available: https://unternehmen.lidl.de/pressreleases/190327_haltungskompass-50-prozent-ziel. [Zugriff am 26.06.2022].

(Own illustration based on 15Lidl Dienstleistung GmbH & Co. KG, „Verantwortung für tierische Produkte,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://unternehmen.lidl.de/verantwortung/handlungsfeld-sortiment/food-sortiment/tierische-produkte. [Zugriff am 28.06.2022].)

Lidl stands out as a pioneer in product labelling. The introduced husbandry levels ensure that consumers are better informed about the products and the ways in which animals are kept. It supports customers in making conscious purchasing decisions and inspires the competition 16Lidl Dienstleistung GmbH & Co. KG, „Rund 50 Prozent des Frischfleischsortiments auf Stufe 2 “Stallhaltung plus”,“ [Online]. Available: https://unternehmen.lidl.de/pressreleases/190327_haltungskompass-50-prozent-ziel. [Zugriff am 26.06.2022]. , 17Lidl Dienstleistung GmbH & Co. KG, „Verantwortung für tierische Produkte,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://unternehmen.lidl.de/verantwortung/handlungsfeld-sortiment/food-sortiment/tierische-produkte. [Zugriff am 28.06.2022].. This example illustrates, that environmental targets should lead to an improvement of the sustainability of products as well as consumption patterns environmentally 18F. Iraldo, R. Griesshammer und W. Kahlenborn, „The future of ecolabels,“ The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, Bd. 5, pp. 833-839, 2020., increase the demand for ecologically friendly products 19M. Delmas und L. Grant, „Eco Labeling Strategies and Price-Premium: the Wine Industry Puzzle,“ Business & Society, Bd. 1, pp. 161-172, 2014. and also reduce environmentally harmful emissions 20F. Fuerst und P. McAllister, „Eco-labeling in commercial office markets: Do LEED and Energy Star offices obtain multiple premiums?,“ Ecological Economics, pp. 1220-1230, 2011..

Together, companies, governments and consumers are helping to ensure that sustainable con-sumption patterns become established in society. Eco-labels help to identify ecological product characteristics and can thus promote sustainable consumption behavior and increase consumer awareness of sustainable consumption 21A. Gerlach und A. Schudak, „Bewertung ökologischer und sozialer Label zur Förderung eines nachhaltigen Konsums,“ Umweltpsychologie, Bd. 2, pp. 30-40, 2010.. Accordingly, the use of eco-labels promotes sustainability without affecting consumers’ liberty of purchasing 22M. Salman, „Eco Labels: Tools of Green Marketing,“ International Research Journal of Management Sociology & Humanity, Bd. 5, pp. 16-23, 2016..

2 Background

Interest in the environment and sustainable techniques was sparked as early in the 1960s. Consequently, eco-taxes or regulatory measures and bans have been enacted since then 23Kritika, S. Kaushal und Abhishek, „Eco-labeling: The Influence of Eco-labeld Products on Consumer Buying Behavior,“ Just Agriculture, pp. 1-5, October 2021.. Governments began to pay more attention to and regulate environmental protection in the early 1970s 24R. Gertz, „Eco-lanelling – a case for deregulation,“ Law, Probability and Risk, pp. 127-141, 2005.. Since the late 1970s, the importance of product labelling and the quality of products and services has also increased. While the original goal of the approach was to protect consumers by providing product information and to optimize their purchasing decisions, product labelling has been expanded to include sustainable aspects of the environment 25F. Iraldo, R. Griesshammer und W. Kahlenborn, „The future of ecolabels,“ The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, Bd. 5, pp. 833-839, 2020..

In addition, consumers became increasingly aware that their extreme consumption leads to negative impacts on the environment. Consequently, interest in environmentally friendly products was aroused and the willingness to buy sustainably increased. This resulted in a public demand for better product information and manufacturers started to decorate their own products with environmental claims 26R. Gertz, „Eco-lanelling – a case for deregulation,“ Law, Probability and Risk, pp. 127-141, 2005..

The first label that was introduced worldwide was the “Blauer Engel”, which appeared on the German market in 1978 and has been regarded as a voluntary, market-based instrument of environmental policy 27RAL gemeinnützige GmbH, „Umweltzeichen mit Geschichte,“ [Online]. Available: https://www.blauer-engel.de/de/blauer-engel/unser-zeichen-fuer-die-umwelt/umweltzeichen-mit-geschichte. [Zugriff am 19.06.2022].. It is still considered a prime example among labels, as it stands for timeliness, reliability, transparency and objectivity. Moreover, the label is characterized by a strong popularity even after 44 years on the market, as it identifies products and services that represent a healthier alternative for the environment and the general welfare, under an evaluation according to strict criteria 28Umweltmission gUG i. G., „Umweltzeichen: Übersicht und Bedeutung,“ [Online]. Available: https://umweltmission.de/wissen/umweltzeichen/#Der_Blaue_Engel_-_ein_bekanntes_Umweltzeichen. [Zugriff am 19.06.2022].. The eco-label has successfully established itself in the business sector and is now used by over 1600 manufacturers to label environmentally friendly everyday products such as detergents, paints or furniture. Thus, the Blauer Engel can now be found on more than 20,000 products as well as services 29RAL gemeinnützige gmbH, „Blauer Engel Produkte und Dienstleistungen,“ [Online]. Available: https://eu-ecolabel.de/eu-ecolabel-das-umweltzeichen-ihres-vertrauens/ueber-das-eu-ecolabel. [Zugriff am 28.06.2022]..

After the Blauer Engel, appeared in 1978, the 1980s were characterized by a multitude of different labels 30F. Iraldo, R. Griesshammer und W. Kahlenborn, „The future of ecolabels,“ The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, Bd. 5, pp. 833-839, 2020.. Thus, from 1980 to 1990, more than 15 different eco-label programs appeared worldwide 31M. Salman, „Eco Labels: Tools of Green Marketing,“ International Research Journal of Management Sociology & Humanity, Bd. 5, pp. 16-23, 2016.. Norway, for example, followed in 1989 with the “Nordic Swan Ecolabel”, which today identifies more than 55 different product groups and 200 various product types in the Nordic countries of Norway, Sweden, Iceland, Finland and Denmark 32N. Ecolabelling, „The official ecolabel of the Nordic countries,“ [Online]. Available: https://www.nordic-ecolabel.org/nordic-swan-ecolabel/. [Zugriff am 19.06.2022]..

Switzerland also followed with its own eco-label “bluesign” in 2000. The aim of introducing bluesign was to encourage manufacturers, brands and chemical suppliers to find sustainable solutions and to create awareness of environmental responsibility. With the introduction of the Restricted Substances List (RSL) of textile chemicals, bluesign ensured that hundreds of tons of chemicals were replaced with environmentally friendly and safe alternatives worldwide. Through the RSL, the label stands out and sets an example for rethinking and leads to numerous environmental improvements. The introduction of the seal also ensures that the UN Sustainable Development Goals can be achieved, setting a milestone for sustainable industrial production. The success of the label is reflected in the 600 companies that mark their products and services with the eco-label 33Bluesign Technologies AG, „Unsere Vision. Unsere Mission,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.bluesign.com/de/business/unsere-geschichte. [Zugriff am 28.06.2022]..

The introduction of the EU Ecolabel also shows that labels have become increasingly important. It was introduced in 1982 in all member states as well as in Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway, identifies products and services that have a low environmental impact 34RAL gemeinnützige GmbH, „Über das EU Ecolabel,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://eu-ecolabel.de/eu-ecolabel-das-umweltzeichen-ihres-vertrauens/ueber-das-eu-ecolabel. [Zugriff am 28.06.2022].. With the implementation of the label, the European Union wants to encourage companies to develop sustainable, durable and innovative products. For example, the EU Ecolabel helps consumers to make sustainable consumption choices and thus contribute to environmental change. Moreover, labels, such as the EU Ecolabel, make the European Union’s environmental targets, such as achieving climate neutrality by 2050 or the goal of a toxic-free environment, more attainable 35E. Commission, „EU Ecolabel,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/circular-economy/eu-ecolabel-home_en. [Zugriff am 28.06.2022]..

True relevance to eco-labels was attached after they were officially identified as a significant issue at the Rio Conference in 1992 in the agenda 21. The Rio Conference is a United Nations conference on the environment and developments that took place in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in 1992. Eco-labels were recommended by the Rio Conference as an essential tool to change consumption habits and thereby protect the environment. It also aims to improve the ecological quality of products 36M. Salman, „Eco Labels: Tools of Green Marketing,“ International Research Journal of Management Sociology & Humanity, Bd. 5, pp. 16-23, 2016..

Following that, in 1994, the Global Ecolabelling Network (hereinafter: GEN) was founded as a “[…] non-profit association of leading ecolabelling organizations worldwide” 37G. E. Network, „GEN: The Global Ecolabelling Network,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://globalecolabelling.net/about/gen-the-global-ecolabelling-network/. [Zugriff am 28.06.2022]., without page. The founding of GEN ensured a significant contribution to environmental protection through its promotion and development of the labelling of environmentally friendly products as well as services 38G. E. Network, „GEN: The Global Ecolabelling Network,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://globalecolabelling.net/about/gen-the-global-ecolabelling-network/. [Zugriff am 28.06.2022].. Products and services that are awarded a GEN label have to meet corresponding environmental performance criteria certified according to a scientifically based standard 39G. E. Network, „What is Ecolabelling?,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://globalecolabelling.net/what-is-eco-labelling/. [Zugriff am 28.06.2022].. Since then, improving consumer information through eco-labels and sustainable development of the environment have been important topics at United Nations conferences, such as the Johannesburg World Summit in 2002 and the Rio+20 Conference in 2012 40M. Salman, „Eco Labels: Tools of Green Marketing,“ International Research Journal of Management Sociology & Humanity, Bd. 5, pp. 16-23, 2016..

In recent years, the demand and supply of green products has grown enormously. Studies show that consumers prefer sustainable products with eco-labels to other products at the same price 41F. Iraldo, R. Griesshammer und W. Kahlenborn, „The future of ecolabels,“ The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, Bd. 5, pp. 833-839, 2020.. As a result of increasing environmental awareness of consumers and regulations of governments, companies are increasingly striving to make their own products and processes more sustainable and environmentally friendly 42M. Salman, „Eco Labels: Tools of Green Marketing,“ International Research Journal of Management Sociology & Humanity, Bd. 5, pp. 16-23, 2016.. The number and importance of eco-labels have grown steadily. Today, in 2022, the eco-label index lists a total of 455 eco-labels in 199 different countries and 25 different economic sectors 43Ecolabel Index, „Ecolabel Index,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.ecolabelindex.com/. [Zugriff am 19.06.2022].. Eco-labelling originally started as a marketing tool to improve the image of one’s own products and has now evolved into an efficient political instrument 44F. Iraldo, R. Griesshammer und W. Kahlenborn, „The future of ecolabels,“ The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, Bd. 5, pp. 833-839, 2020..

3 Practical implications

3.1 International Organization for Standardization

The categorisation and classification of eco-labels for products and services takes place in different ways. A distinction is made between mandatory and voluntary systems and whether the certification is dependent or independent. Mandatory environmental labels, which are required by law, include, for example, energy- or water-consuming appliances 45R. E. Horne, „Limits to labels: The role of eco-labels in the assessment,“ International Journal of Consumer Studies, Bd. 33, pp. 175-182, 2009.. Overall, mandatory labels are rather an exception compared to voluntary ones 46M. Yokessa und S. Marette, „A Review of Eco-labels and their,“ International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Bd. 13, pp. 119-163, 2019., so most attention is given to the voluntary eco-labels in this wiki. Therefore, the International Organization for Standardization (hereinafter: ISO) has formed three different categories für voluntary labelling: Type I, Type II and Type III 47ISO, „Environmental labels and declarations — Type I environmental labelling — Principles and procedures,“ 1999. [Online]. Available: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:14024:ed-1:v1:en. [Zugriff am 24.06.2022]., as shown in figure two.

Type I is also called “eco-label” in the literature because the certified products receive a logo on the packaging. The certification of the products is not carried out by ISO itself, but by third parties. ISO Type I labels cover a wide range of product categories. In opposition to this, there are also Type I-like labels, beyond ISO, that classifies exactly one product category 48R. E. Horne, „Limits to labels: The role of eco-labels in the assessment,“ International Journal of Consumer Studies, Bd. 33, pp. 175-182, 2009.. In addition, the literature shows that Type I labels have a high reliability and verifiability 49M. Koszewska, „Social and Eco-labelling of Textile and Clothing Goods as Means of,“ FIBRES & TEXTILES, Bd. 19, Nr. 4 (87), pp. 20-26, 2011..

Self-declarations form the basis of Type II. These can be made by different companies, such as manufacturers, retailers or importers. In contrast, a detailed report is the basis of Type III labelling. This contains quantitative environmental data over the entire life cycle of, for example, a product 50R. E. Horne, „Limits to labels: The role of eco-labels in the assessment,“ International Journal of Consumer Studies, Bd. 33, pp. 175-182, 2009..

Besides the ISO classifications, there are three other types of eco-labels: Corporate/Organization labelling, Package labelling and Industry labelling, which are also illustrated by figure two Companies that manufacture or sell products can use corporate labelling. It should be noted that the environmental requirements of the organisation are not related to those of any of its products. Packaging labelling is about how sustainable the packaging of a product is, not how sustainable the product itself is. Industry labelling indicates that it is specific to an industry. For example, this could be agriculture, forestry or textile industry 51M. Koszewska, „Social and Eco-labelling of Textile and Clothing Goods as Means of,“ FIBRES & TEXTILES, Bd. 19, Nr. 4 (87), pp. 20-26, 2011.. Among other things, the next chapter concentrates on the topic of industry labelling and includes some examples of eco labelling.

(Own illustration based on 52M. Koszewska, „Social and Eco-labelling of Textile and Clothing Goods as Means of,“ FIBRES & TEXTILES, Bd. 19, Nr. 4 (87), pp. 20-26, 2011., p. 22)

3.2 Field of application

Eco-labels are represented in many different application areas and can therefore also be characterized according to criteria such as

- communication channel,

- environmental attribute,

- category of goods and services targeted,

- type of control,

- ownership and

- scope 53M. Yokessa und S. Marette, „A Review of Eco-labels and their,“ International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Bd. 13, pp. 119-163, 2019..

The communication channel deals with the connections between consumer, company and government. A label can communicate business-to-consumer, business-to-business, government-to-consumer or business-to-government 54M. Yokessa und S. Marette, „A Review of Eco-labels and their,“ International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Bd. 13, pp. 119-163, 2019.. Examples for seals for government-to-consumer are the german eco-label Blauer Engel of the Federal Ministry for the Environment 55RAL gGbmH, „Das deutsche Umweltzeichen,“ 2022a. [Online]. Available: https://www.blauer-engel.de.de. [Zugriff am 17.06.2022]. and the EU Ecolabel 56RAL GmbH, „Was ist das EU Ecolabel?,“ 2022b. [Online]. Available: https://eu-ecolabel.de. [Zugriff am 17.06.2022]., as mentioned in chapter two. The environmental attribute includes factors such as natural resources, sustainability and biodiversity.

Food, tourist services and textile products are some examples for the category of goods and services of labels. As explained in the previous chapter, it concerns industry labelling. Especially in the food industry, seals are used tactically and it is no longer possible to imagine packaging design without them 57MTP, „Ökologische Siegel und wie sie das Kaufverhalten beeinflussen,“ 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.mtp.org/magazin/2021/03/15/oekologische-siegel-und-wie-sie-das-kaufverhalten-beeinflussen-mtp-e-v. [Zugriff am 18.06.2022].. A study by Utopia clearly shows that consumers pay most attention to labels in the food sector 58Utopia GmbH, „Lost in Label? Welchen Siegeln bewusste Konsumenten am meisten vertrauen – Siegel Studie,“ 2019. [Online]. Available: https://i.utopia.de/sales/utopia-siegel-studie-lost-in-label-2019.pdf. [Zugriff am 18.06.2022].. An important label in the food industry, for example, is the Marine Stewardship Council (hereinafter: MSC) because it is the world’s strictest environmental label for wild fish. The MSC seal stands for fish products from sustainable, environmentally friendly fisheries. Moreover, the international certification program with strict environmental criteria protects seas and fish stocks and to stop overfishing and minimize the negative impact of fishing on the marine ecosystem is the non-governmental organizations (hereinafter: NGO) goal 59MSC, „Wofür steht das MSC-Siegel?,“ 2022a. [Online]. Available: https://www.msc.org/de/ueber-uns/der-msc. [Zugriff am 18.06.2022].. To be certified as a fishery, three standards must be achieved. These include that the fish stock is in good condition, the marine habitat is protected and the fishery has an effective management. Unlike other labels, each individual certified fishery is audited by independent assessors against the MSC standard 60MSC, „Der MSC,“ 2022b. [Online]. Available: https://www.msc.org/de. [Zugriff am 18.06.2022]..

In addition, labels are spreading in more and more sectors 61MTP, „Ökologische Siegel und wie sie das Kaufverhalten beeinflussen,“ 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.mtp.org/magazin/2021/03/15/oekologische-siegel-und-wie-sie-das-kaufverhalten-beeinflussen-mtp-e-v. [Zugriff am 18.06.2022].. Meanwhile, there are also some eco-labels in the tourism sector. These include labels like “Green Globe” and “Blue Flag” by the Foundation for Environmental Education (hereinafter: FEE), which stands among other things for beaches that signal clean water and a clean coastline 62M. Yokessa und S. Marette, „A Review of Eco-labels and their,“ International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Bd. 13, pp. 119-163, 2019. , 63FEE, „Our programme,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.blueflag.global/our-programme. [Zugriff am 18.06.2022].. The Green Globe certificate is characterised by the fact that it was developed specifically for the tourism industry 64FairWeg GmbH, „Das Green Globe Zertifikat,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://fairweg.de/nachhaltigkeits-zertifikate/green-globe/.. [Zugriff am 18.06.2022].. Moreover, the organisation is the world leader in the field of sustainable tourism certification. Hotels, resorts, conference centres and attractions have been certified and memberships awarded to businesses for 30 years 65Green Globe Certification, „The global leader in Sustainable Tourism Certification,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.greenglobe.com/.. [Zugriff am 18.06.2022]..

There is also a lot of labelling in the energy sector for electrical appliances and energy efficiency 66M. Yokessa und S. Marette, „A Review of Eco-labels and their,“ International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Bd. 13, pp. 119-163, 2019.. A well-known example from the energy sector is the “European Union energy label”. It can be found on many products with a colour scale from dark green, which is very satisfying, to red, which is substandard. This scale serves as a quick guide to how energy-efficient a product is. In addition, the label gives further helpful information for customers, like the annual energy consumption mfn]Bundesrepublik Deutschland, „EU-Energielabel,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/umwelttipps-fuer-den-alltag/siegelkunde/eu-energielabel. [Zugriff am 19.06.2022].[/mfn]. This is important because studies have shown that besides labels, information can help to reduce energy consumption 67M. Yokessa und S. Marette, „A Review of Eco-labels and their,“ International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Bd. 13, pp. 119-163, 2019.. A result of an environmental awareness study also showed that the European Union energy label has the highest influence on the purchase decision compared to other environmental labels 68Bundesrepublik Deutschland, „EU-Energielabel,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/umwelttipps-fuer-den-alltag/siegelkunde/eu-energielabel. [Zugriff am 19.06.2022]..

Labelling is also gaining importance in the textile and fashion industry as well as in the agriculture and forestry 69MTP, „Ökologische Siegel und wie sie das Kaufverhalten beeinflussen,“ 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.mtp.org/magazin/2021/03/15/oekologische-siegel-und-wie-sie-das-kaufverhalten-beeinflussen-mtp-e-v. [Zugriff am 18.06.2022].. Besides the already mentioned bluesign label, the “Global Organic Textile Standard” (hereinafter: GOTS) is a well-known label in the textile industry. The goal is to establish a worldwide unified, social and ecological standard for textile production. The GOTS standard aims to make the entire textile supply chain traceable. Products that receive the label consist of at least 70 percent ecologically produced natural fibres 70Producto GmbH, „Nachhaltigkeitssiegel: Das sind die Guten,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.testberichte.de/magazin/umweltsiegel-und-ihre-bedeutung.html. [Zugriff am 19.06.2022].. In the wood processing industry, there is the Forest Stewardship Council (hereinafter: FSC) certification. The organisation behind this label ensures important environmental and social standards in the forest, which apply worldwide. Moreover, the label stands for “forests forever for all”, so that the needs of future generations are also covered. The whole inspection to obtain a certificate is carried out by a third party and is repeated annually. Worldwide, around 230,000,000 hectares of forest are FSC-certified and around 51,000 FSC product chain certificates have been awarded 71Verein für verantwortungsvolle Landwirtschaft e.V., „FSC steht für: Wälder für immer für alle,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.fsc-deutschland.de/was-ist-fsc/. [Zugriff am 25.06.2022]..

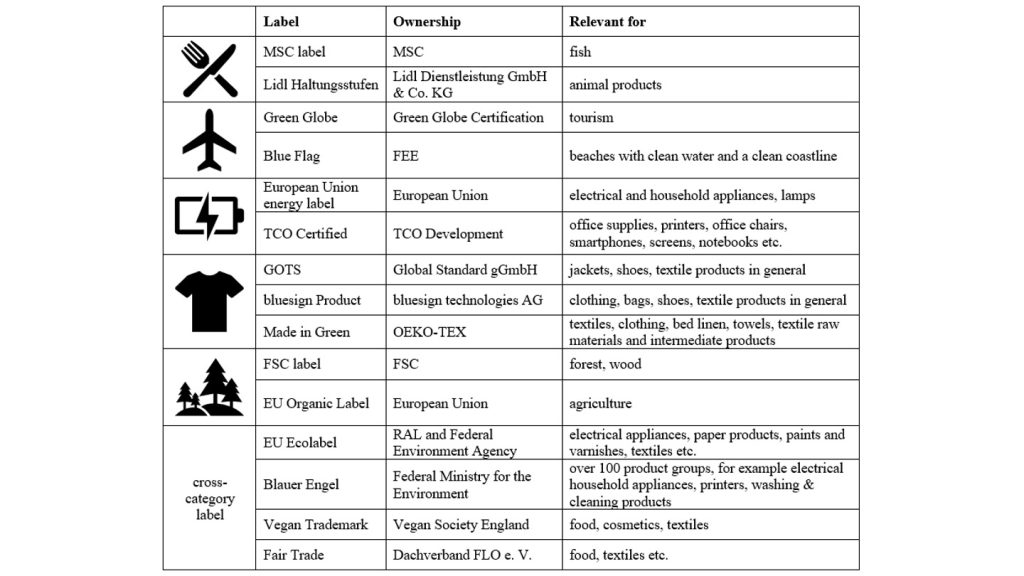

A further criterion is the scope of application, which determines whether a label is valid regionally, nationally or even internationally 72M. Yokessa und S. Marette, „A Review of Eco-labels and their,“ International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Bd. 13, pp. 119-163, 2019.. Moreover, the ownership of an eco-label is important for the credibility of a product. For the most part, these are owned by NGOs or private institutions. It also should be mentioned that organic labels are a special case in this respect, as they have to fulfil certain characteristics in any case, regardless of who the owner is 73M. Yokessa und S. Marette, „A Review of Eco-labels and their,“ International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Bd. 13, pp. 119-163, 2019.. The “EU Organic Label” is a label that is both internationally valid and an organic label. The EU Organic Label is awarded by the European Union and aims to promote more sustainable agriculture 74A. Winterer, „EU-Bio-Siegel: Diese Dinge sind bei Bio verboten,“ 2021. [Online]. Available: https://utopia.de/siegel/eu-bio-siegel/. [Zugriff am 24.06.2022].. In the following figure, some different labels are once again summarised according to different categories.

(Own illustration based on 75Producto GmbH, „Nachhaltigkeitssiegel: Das sind die Guten,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.testberichte.de/magazin/umweltsiegel-und-ihre-bedeutung.html. [Zugriff am 19.06.2022]. and information from chapter 3.2)

In this chapter it became clear that there is a large number of diverse labels that are used in many different sectors. Therefore, labels should fulfil certain requirements so that they become decisive for consumers and thus profitable for companies. These requirements will be discussed in detail in the next chapter.

3.3 Requirements for a good label

In connection with the requirements for a label, the question arises whether the different labels promote sustainable consumption or not. For this purpose, a look should be taken at the four “familiar sustainability principles including carrying capacity, conservation of natural capital, intergenerational equity and participative democracy” 76R. E. Horne, „Limits to labels: The role of eco-labels in the assessment,“ International Journal of Consumer Studies, Bd. 33, pp. 175-182, 2009, p. 176.. From these sustainability principles, in turn, four themes can be derived that a label should include in order to be a strong label:

- coverage

- involvement of stakeholder needs

- uptake, acceptance and independence

- sustainable consumption outcomes, measured environment 77R. E. Horne, „Limits to labels: The role of eco-labels in the assessment,“ International Journal of Consumer Studies, Bd. 33, pp. 175-182, 2009..

Furthermore, Meis-Harris et al. set out six conditions in their paper that are necessary for a label to make a difference. Therefore, trust in label plays an important role 78J. Meis-Harris, C. Klemm, S. Kaufman, J. Curtis, K. Borg und P. Bragge, „What is the role of eco-labels for a circular economy? A rapid review,“ Journal of Cleaner Production, Bd. 306, pp. 1-16, 2021.. In particular, if the sources of environmental information are from credible consumer organisations or NGOs, rather than the retailer or creator themselves, the customers trust is higher 79M. Yokessa und S. Marette, „A Review of Eco-labels and their,“ International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Bd. 13, pp. 119-163, 2019.. From this follows the first condition that labels should be transparent, trustworthy and contain accurate information about the product, according to the agreed criteria for the label 80J. Meis-Harris, C. Klemm, S. Kaufman, J. Curtis, K. Borg und P. Bragge, „What is the role of eco-labels for a circular economy? A rapid review,“ Journal of Cleaner Production, Bd. 306, pp. 1-16, 2021.. Consumers will also be more influenced in their purchasing decisions when sources are based on technical expertise 81B. Sternthal, L. W. Phillips und R. Dholakia, „The persuasive effect of scarce credibility: a situational analysis,“ Publ. Opin., Bd. 3, pp. 285-341, 1978..

The second point of a successful label is information on the label, which should be clearly visible to the consumer. Information plays a major role in key moments of decision-making, for example at the point of sale, and should be considered in the design 82J. Meis-Harris, C. Klemm, S. Kaufman, J. Curtis, K. Borg und P. Bragge, „What is the role of eco-labels for a circular economy? A rapid review,“ Journal of Cleaner Production, Bd. 306, pp. 1-16, 2021.. The instructions should be clear, easy to understand and realise the required behaviour, for example the purchase of a product 83M. Kools, „Making written materials easy to understand,“ in Writing Health Communication: an Evidence-Based Guide, London, Sage Publications, 2011, pp. 23-42..

For the third condition, tangible environmental data should be used for product labelling criteria. In this way, consumers are more likely to recognise the environmental benefits compared to a product that is not certified and, as a result, are more likely to choose a certified product. Therefore, direct information on how, for example, the certified product reduces resource consumption, is useful 84J. Meis-Harris, C. Klemm, S. Kaufman, J. Curtis, K. Borg und P. Bragge, „What is the role of eco-labels for a circular economy? A rapid review,“ Journal of Cleaner Production, Bd. 306, pp. 1-16, 2021..

As a fourth condition, it was stated that the purpose and objectives of labels must be understood and valued by consumers. It can be concluded that labels should address the values of consumers. In this respect, it is important to address a segmented target group with tailored communication measures 85J. Meis-Harris, C. Klemm, S. Kaufman, J. Curtis, K. Borg und P. Bragge, „What is the role of eco-labels for a circular economy? A rapid review,“ Journal of Cleaner Production, Bd. 306, pp. 1-16, 2021.. In addition, personal benefits of consumers through the purchase of a certified product should always be highlighted 86K. M. R. Taufique, C. Siwar, B. Talib, F. H. Sarah und N. Chamhuri, „Synthesis of constructs for modeling consumers’ understanding and perception of eco-labels,“ Sustainability, Bd. 6, Nr. 4, pp. 2176-2200, 2014..

Sufficient market penetration is one another factor that must be fulfilled for a label to be both successful and profitable. One way to achieve this is to participate in third-party labelling schemes. This additionally increases consumer trust and also reduces the risk of so called “greenwashing” which is further explained in chapter 4.1.1 87J. Meis-Harris, C. Klemm, S. Kaufman, J. Curtis, K. Borg und P. Bragge, „What is the role of eco-labels for a circular economy? A rapid review,“ Journal of Cleaner Production, Bd. 306, pp. 1-16, 2021..

The last condition states that labels usually do not work without further political instructions. For people without environmental awareness in particular, labels have hardly any influence on their purchasing decisions. In order to increase this influence, government regulations and restrictions are needed. The combination of both can lead to the promotion of sustainable consumption 88J. Meis-Harris, C. Klemm, S. Kaufman, J. Curtis, K. Borg und P. Bragge, „What is the role of eco-labels for a circular economy? A rapid review,“ Journal of Cleaner Production, Bd. 306, pp. 1-16, 2021..

All in all, it can be concluded from the number of eco-labels that consumers no longer have a proper overview. It is often unclear which eco-label can be trusted and which cannot. It should be noted that the seals that are not understood by consumers, are also the least likely to be included in purchasing decisions 89MTP, „Ökologische Siegel und wie sie das Kaufverhalten beeinflussen,“ 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.mtp.org/magazin/2021/03/15/oekologische-siegel-und-wie-sie-das-kaufverhalten-beeinflussen-mtp-e-v. [Zugriff am 18.06.2022].. This point is also crucial for companies, because it is important for them to develop or use a label that is as transparent and easy to understand as possible for customers. Furthermore, it seems important for companies to stand out from the crowd with their label in order to secure a market advantage.

In conclusion, labels play a major role especially in the essential areas of life, such as nutrition. However, labels in other product categories should continue to be expanded, as younger generations in particular have a more sustainable attitude. Ecological labels will continue to be important in marketing, but also for reputation of the brand itself. The “trend” towards sustainability should therefore not be underestimated 90MTP, „Ökologische Siegel und wie sie das Kaufverhalten beeinflussen,“ 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.mtp.org/magazin/2021/03/15/oekologische-siegel-und-wie-sie-das-kaufverhalten-beeinflussen-mtp-e-v. [Zugriff am 18.06.2022].. After the requirements and importance of labels have been highlighted in this chapter, the next chapter will look at how a company can introduce a label.

3.4 Implementation of eco-labels in companies

The basis for certainty about the correct planning and implementation of environmental policies is the separation of powers. An independent third party oversees standardization during the planning phase. An additional independent third party checks during the implementation phase whether the standards of the certification are complied with by the manufacturer, i.e. the company. If this is the case, the certification body issues a so-called declaration of conformity, which confirms that the company has acted in compliance with the standard. However, there is usually no other independent party that ultimately measures and monitors the results of the environmental label. Labels therefore do not necessarily promise that the product itself meets certain standards, but merely that the production process conforms to the certification 91M. Van Amstel, P. Driessen und P. Glasbergen, „Eco-labeling and information asymmetry: a comparison of five eco-labels in the Netherlands,“ Journal of Cleaner Production, Bd. 16, Nr. 3, pp. 263-276, 2008..

To show exemplary how companies can have its products certified, the FSC label will be used as an example. A total of five steps are necessary for this. First, the company should inform itself about a possible certifier. Then it must decide on a certification authority with which the company will cooperate in the future and also conclude a contract. This is followed by an audit. The reason for this is to find out whether the company is suitable for certification. In the fourth step, the data collected is checked by the responsible certifier and forms the basis of the certifier’s decision. If the company and the product meet all the requirements, it receives the FSC certificate and can label its products accordingly. The certificate is valid for five years and there are also annual inspections by the certifier. After five years, the entire management system and the products are audited again 92Gutes Holz Service GmbH, „FSC-Produktkettenzertifizierung,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.fsc-deutschland.de/verarbeitung-handel/produktkettenzertifizierung/. [Zugriff am 03.07.2022]..

The FSC requires different standards. These include the establishment of a management system in the company and the introduction of a monitoring system that specifies how material flows can be controlled. In addition, the use of subcontractors must be regulated and product labelling must be defined. In order to meet the requirements and to obtain the certificate, the company incurs some costs. These are, on the one hand, internal costs, for example, to adapt operating procedures, to train staff or to make changes in purchasing and goods receipt. On the other hand, there may be costs for an external consultant who can provide support if needed. In addition, there are external costs for the recognised FSC certification authority and costs for the FSC certificate fee. This is a considerable cost factor, especially for smaller companies. It therefore makes sense to check whether there is the possibility of group certification for small companies. The FSC has a threshold so that small companies can join a group. This can save costs and an exchange can help to reduce the internal effort. There are also support programmes from the federal government or the federal states that offer advice and even support certification. 93Gutes Holz Service GmbH, „FSC-Produktkettenzertifizierung,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.fsc-deutschland.de/verarbeitung-handel/produktkettenzertifizierung/. [Zugriff am 03.07.2022].. One example is the “Sächsische Aufbaubank” support programme for environmental management 94Sächsische Aufbaubank – Förderbank –, „Sie möchten ein Unternehmen gründen, in Ihr Unternehmen investieren oder Ihre Geschäftstätigkeit ausbauen?,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.sab.sachsen.de/f%C3%B6rderprogramme/sie-m%C3%B6chten-ein-unternehmen-gr%C3%BCnden-in-ihr-unternehmen-investieren-oder-ihre-gesch%C3%A4ftst%C3%A4tigkeit-ausbauen/index.jsp. [Zugriff am 05.07.2022]..

Finally, companies are allowed to label products they manufacture that have been FSC-certified. In addition, they are also allowed to use the labels for communicative and promotional purposes. It should be noted that FSC membership alone is not sufficient to label products 95Gutes Holz Service GmbH, „FSC-Warenzeichen,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.fsc-deutschland.de/verarbeitung-handel/produktkettenzertifizierung/fsc-warenzeichen/. [Zugriff am 02.07.2022].. In addition, any abuse or infringement of the property rights will be disciplined from the organization 96Gutes Holz Service GmbH, „Verletzungen des FSC-Warenzeichenschutzes,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.fsc-deutschland.de/verarbeitung-handel/schutzrechtsverletzung/. [Zugriff am 02.07.2022]..

4 Drivers and barriers

4.1 Drivers

4.1.1 Drivers for companies

The implication of eco-labels can be beneficial for companies, as well as consumers, through various drivers. First of all, a number of factors influencing eco-labels for companies will be considered. These factors can influence the adaptation, endorsement, or production of new products to qualify for eco-label certification 97J. Meis-Harris, C. Klemm, S. Kaufman, J. Curtis, K. Borg und P. Bragge, „What is the role of eco-labels for a circular economy? A rapid review,“ Journal of Cleaner Production, Bd. 306, pp. 1-16, 2021..

Most companies adopt eco-labels voluntarily, as explained in chapter three. The use of such a label serves to inform consumers about the environmental characteristics of a product and can therefore be considered as a strategic decision 98M. Yokessa und S. Marette, „A Review of Eco-labels and their,“ International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Bd. 13, pp. 119-163, 2019.. Consequently, labelling is a way to differentiate a company’s goods and offer consumers greater added value than competing firms 99V. Prieto-Sandoval, J. Alfaro, A. Mejía-Villa und M. Ormazabal, „Eco-labels as a multidimensional research topic: trends and opportunities,“ Journal of Cleaner Production, Bd. 135, pp. 806-818, 2016.. There is also the opportunity for increased sales through greater consumer choice in the rising green retail environment 100R. E. Horne, „Limits to labels: The role of eco-labels in the assessment,“ International Journal of Consumer Studies, Bd. 33, pp. 175-182, 2009.. Furthermore, if consumers have a higher willingness to pay (hereinafter: WTP) for products with good environmental quality and or a low WTP for goods with low environmental quality, the communication of sustainability aspects through eco-labels can be a great incentive for companies to improve the environmental characteristics of their products. However, the line between communication and real environmental improvement seems to be very narrow and fragile in this sense. Companies are often accused of greenwashing in this context, which implies that an outrageous environmental claim is made in order to hide the actual lack of efforts to improve the environmental characteristics of a product. This negative effect is often based on the seriousness of the certification, which, as described in chapter three, can be carried out by independent certification organizations as well as private companies 101M. Yokessa und S. Marette, „A Review of Eco-labels and their,“ International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Bd. 13, pp. 119-163, 2019.. To cite an example for the greenwashing effect Ikea claims to almost exclusively use wood certified through the NGO FSC and labels its products with the FSC-label. In contrast to Ikeas claims, independent research documents logging activities not adhering to the FSC guidelines. Its activities include deforestation of Romanian old-growth forests and the wrongful declaration of its products 102IKEA, „Nachhaltige Forstwirtschaft bei IKEA: Was steckt dahinter?,“ IKEA, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.ikea.com/de/de/this-is-ikea/corporate-blog/nachhaltige-forstwirtschaft-pub86eb6850. [Zugriff am 26.07.2022]. , 103Agent Green, „HYPOCRISY! IKEA’S CYNICAL DESTRUCTION OF ROMANIA’S OLD-GROWTH FORESTS,“ 26 08 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.agentgreen.ro/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/20210826_IKEA_hipocrisy_EN.pdf. [Zugriff am 26.07.2022]..

Another positive entrepreneurial influence can be exerted by social influences and those affecting the consumer. For example, eco-labelling can improve the reputation of a brand 104J. Meis-Harris, C. Klemm, S. Kaufman, J. Curtis, K. Borg und P. Bragge, „What is the role of eco-labels for a circular economy? A rapid review,“ Journal of Cleaner Production, Bd. 306, pp. 1-16, 2021.. Studies also show that the value of supermarket brands can be increased by the introduction of eco-labels. However, labelling did not lead to a rise in the value of goods if well-known products or brands already had nutritional labelling anyway 105M. Yokessa und S. Marette, „A Review of Eco-labels and their,“ International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Bd. 13, pp. 119-163, 2019.. Labelling can therefore increase the value of goods in certain cases, which can be associated with an increase in sales and turnover. However, eco-labelling can also be introduced to respond to society’s demand for more environmentally friendly products. In particular, societal pressure as well as pressure from shareholders or important customers can have a decisive influence on a company’s attitude regarding an environmental label 106J. Meis-Harris, C. Klemm, S. Kaufman, J. Curtis, K. Borg und P. Bragge, „What is the role of eco-labels for a circular economy? A rapid review,“ Journal of Cleaner Production, Bd. 306, pp. 1-16, 2021..

Furthermore, economic factors play a decisive role in the decision for or against an eco-label. These include, for example, forecasts as to whether certified products have sufficient market penetration and differentiation from competing products to cover costs that arise. These can include costs for the certification process or costs for necessary production processes and material flows. Besides that, eco-labels also offer the opportunity to enter new potential markets that were previously excluded by legal boundaries. Additionally, existence in markets under new, possibly mandatory circular economy (hereinafter: CE) requirements can be secured 107J. Meis-Harris, C. Klemm, S. Kaufman, J. Curtis, K. Borg und P. Bragge, „What is the role of eco-labels for a circular economy? A rapid review,“ Journal of Cleaner Production, Bd. 306, pp. 1-16, 2021..

Beyond that, operational influencing factors form an important aspect. These deal with whether a company has sufficient control over its supply chain to ensure compliance with environmental labelling requirements. This is also beneficial for maintaining brand reputation. Supplementary to that, however, it may also be beneficial to require or encourage suppliers to participate in the labelling system. However, this only seems to be beneficial if it also meets their needs 108V. Prieto-Sandoval, J. Alfaro, A. Mejía-Villa und M. Ormazabal, „Eco-labels as a multidimensional research topic: trends and opportunities,“ Journal of Cleaner Production, Bd. 135, pp. 806-818, 2016. , 109M. Yokessa und S. Marette, „A Review of Eco-labels and their,“ International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Bd. 13, pp. 119-163, 2019..

Moreover, there are ecological influences that aim to determine whether labelling systems actually fulfil what they promise (for example, based on CE results) and are not, as already alluded to, merely a form of greenwashing to encourage less environmentally oriented competitor companies to adopt them. However, this is complicated by the multi-faceted nature of sustainability more broadly and fuzzy definitions of CE. Accordingly, a heterogeneous group of companies and consumers may disagree on what attributes and CE outcomes a particular label should guarantee 110J. Meis-Harris, C. Klemm, S. Kaufman, J. Curtis, K. Borg und P. Bragge, „What is the role of eco-labels for a circular economy? A rapid review,“ Journal of Cleaner Production, Bd. 306, pp. 1-16, 2021. , 111V. Prieto-Sandoval, J. Alfaro, A. Mejía-Villa und M. Ormazabal, „Eco-labels as a multidimensional research topic: trends and opportunities,“ Journal of Cleaner Production, Bd. 135, pp. 806-818, 2016..

Finally, companies may not be interested in meeting environmental or voluntary certification program goals if they are not linked to mandatory, legal labelling requirements. Political influence thus also assumes a major positional value in the context of environmental certification 112J. Meis-Harris, C. Klemm, S. Kaufman, J. Curtis, K. Borg und P. Bragge, „What is the role of eco-labels for a circular economy? A rapid review,“ Journal of Cleaner Production, Bd. 306, pp. 1-16, 2021.. Therefore, the role of government in the context of environmental certifications is considered again in more detail in a subsequent chapter.

4.1.2 Drivers for consumers

While the previous drivers focused on companies, a number of factors influencing eco-labels that relate to consumers will now also be discussed. Therefore, this chapter concentrates on what consumers are looking for in an eco-label and what the use cases are. As discussed before, one main purpose of eco-labels is the communication of efforts taken to increase a products eco-friendliness and positively influence a brands reputation among potential customers and consequently increase sales 113J. Meis-Harris, C. Klemm, S. Kaufman, J. Curtis, K. Borg und P. Bragge, „What is the role of eco-labels for a circular economy? A rapid review,“ Journal of Cleaner Production, Bd. 306, pp. 1-16, 2021. , 114V. Prieto-Sandoval, J. Alfaro, A. Mejía-Villa und M. Ormazabal, „Eco-labels as a multidimensional research topic: trends and opportunities,“ Journal of Cleaner Production, Bd. 135, pp. 806-818, 2016..

From a customer perspective this communication assists in making buying decisions with customers looking to a product`s eco-certifications as they look for assistance for their decision-making 115F. &. B. M. Iraldo, „Drivers, Barriers and Benefits of the EU Ecolabel in European Companies’ Perception,“ Sustainability, Nr. 9, 2017.. This demand guides customers looking for greener options towards labelled products and subsequently exerts pressure on producers to adapt measures towards more environment friendly design and production processes. To ensure the market mechanisms to work the customers need the support of governing bodies to ensure reliable and trustworthy eco-labels 116F. Testa, F. Iraldo, A. Vaccari und E. Ferrari, „Why Eco-labels can be Effective Marketing Tools: Evidence from a Study on Italian Consumers.,“ Business Strategy and the Environment, Bd. 24, Nr. 4, pp. 252-265, 2015.. Here, the German drugstore dm uses its own eco-labels to visibly inform customers about ecological aspects of its own brands. To strengthen the communication of their actions towards more sustainable products they implemented multiple labels indicating for example sustainable production and packaging and microplastic-free products. Adding to this, dm informs its customers about the set standards for its labels through the website and online store 117dm, „„Mikroplastik“ – ein komplexer Sachverhalt,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.dm.de/tipps-und-trends/nachhaltigkeit/mikroplastik. [Zugriff am 04.08.2022]. , 118dm, „Produkte mit Umweltsiegel bei dm,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.dm.de/tipps-und-trends/nachhaltigkeit/umweltsiegel. [Zugriff am 04.08.2022]..

The aforementioned effects are strengthened through the evaluation of an official third-party labelling body such as the EU Ecolabel as they appear more trustworthy to customers. This in turn leads to stronger market positions and can serve as an opportunity when competing with strong brands to overcome customer brand loyalty. A market with a strong brand influence is the fashion industry 119F. Testa, F. Iraldo, A. Vaccari und E. Ferrari, „Why Eco-labels can be Effective Marketing Tools: Evidence from a Study on Italian Consumers.,“ Business Strategy and the Environment, Bd. 24, Nr. 4, pp. 252-265, 2015.. As a prime example Nike is one of the most known clothing brands worldwide. Apart from the name, the logo of the company is one of the most famous logos and makes Nike´s products immediately recognizable 120D. C. Wijdeveld, „How fashion startups build strong brands: Exploring industry-specific factors most influential when branding fashion startups.,“ University of Twente, Twente, 2018..

Another important aspect is the change in the green customer profile as old views of an undifferentiated group of buyers with ecologically conscious buying behaviour are long outdated. Present and future customers become more and more differentiated as they firstly appear across nearly all markets and secondly consider gradients as to what a green and environmentally friendly products attributes are. The division by simply using demographic indicators may no longer be an accurate measure to form target groups and allows for stronger competition on the shelves and websites 121F. Testa, F. Iraldo, A. Vaccari und E. Ferrari, „Why Eco-labels can be Effective Marketing Tools: Evidence from a Study on Italian Consumers.,“ Business Strategy and the Environment, Bd. 24, Nr. 4, pp. 252-265, 2015. , 122R. J. Straughan RD, „Environmental segmentation alternatives: a look at green consumer behavior in the new millennium.,“ Journal of Cosumer Marketing, Nr. 16, pp. 558-575, 1999..

4.2 Barriers

4.2.1 Barriers for companies

Contrary to the listed drivers of eco-labelling, the following issues represent barriers in the context of environmental certification. As already mentioned, greenwashing effects represent an important barrier for companies in adopting eco-labels. In the context of the problem of greenwashing, the presence of inconsistent CSR information leads to a company being perceived as hypocritical by consumers. This can have a negative impact on consumer attitudes. However, it can also be noted at this point that there does not seem to be any scientific consensus, as some studies have not been able to demonstrate this effect 123M. A. Delmas und V. Burbano, „The drivers of greenwashing,“ California Management Review, Bd. 54, Nr. 1, pp. 64-87, 2011.. Customer naivety also crystallized as an important influencing factor. Consumers tend to overestimate their own WTP for products with good environmental characteristics. Furthermore, awareness of these characteristics does not automatically lead to changes in the purchasing behaviour of a consumer. Thus, research shows that a customer’s fundamentally positive attitude toward an eco-label is not a reliable predictor of a greener buying behavior 124C. Leire und A. Thidell, „Product-related environmental information to guide consumer purchases – A review and analysis of research on perceptions, understanding and use among Nordic consumers,“ Journal of Cleaner Production, Bd. 13, pp. 1061-1070, 2005. , 125M. Magnusson, A. Arvola, U.-K. Koivisto Hursti, L. Aberg und P. Sjoden, „Attitudes towards organic foods among Swedish consumers,“ British Food Journal, Bd. 103, pp. 209-227, 2001. , 126A. Reiser und D. Simmons, „A quasi-experimental method for testing the efectiveness of ecolabel promotion,“ Journal of Sustainable Tourism, Bd. 13, pp. 590-616, 2005..

Another barrier that tempts managers to hesitate in adopting an eco-label is the fear of environmental or quality reputation damage. An example of negative labelling reputation are the U.S. organic brands Aurora and Horizon. In April 2007, a boycott was initiated by the U.S. Organic Consumers Association against these two brands because they mislabelled their products “USDA Organic” when in fact the milk used was from factory farms. This example underscores that organic label with untrustworthy or confusing claims, can damage the reputation of firms. Consequently, the reputation of other companies can also be indirectly damaged if they use other, credible labels, but these are related to the negatively afflicted one 127N. Darnall, „Creating a green brand for competitive distinction,“ Asian Business & Management, Bd. 7, pp. 445-466, 2008..

A general problem for researchers and practitioners also seems to be making eco-labels usable and visible to consumers across all sectors of the economy, and not just to “green” customers in well-developed industrialized nations. This does not seem surprising, since it is precisely nations such as Germany, Japan, and the United States that have decisively initialized and shaped the practice of eco-labelling, as presented in chapter two. As a result, the national populations of these countries have also been familiar with the concept of environmental certification for longer than in developing or emerging countries 128V. Prieto-Sandoval, J. Alfaro, A. Mejía-Villa und M. Ormazabal, „Eco-labels as a multidimensional research topic: trends and opportunities,“ Journal of Cleaner Production, Bd. 135, pp. 806-818, 2016..

4.2.2 Barriers for consumers

The goal of eco-labels to promote and support the consumption of more environmentally friendly products and services by supporting customers in their decision making may not always be reached 129F. Rubik, P. Frankl, L. Pietroni und D. Scheer, „Eco-labelling and consumers: towards a re-focus and integrated approaches,“ International Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development, Bd. 2, Nr. 2, pp. 175-191, 2002.. This might be the case as there are instances in which eco-labelling show contrary results and discourages customers to buy labelled products with various reasoning behind these decisions 130M. Delmas, „PERCEPTION OF ECO-LABELS: ORGANIC AND BIODYNAMIC WINES,“ UCLA Institute of the Environment and Anderson School of Management, Los Angeles, CA, 2008..

An important aspect when looking into eco-labelling is that consumers may encounter difficulties in identifying truly responsible companies and products from false claims and greenwashing due to label profusion. This results in lower trust in labels in general and the bad reputation harms even responsible companies adhering to the set standards of the used labels 131J. Gosselt, T. van Rompay und L. Haske, „Won’t Get Fooled Again: The Effects of Internal and External CSR ECO-Labeling,“ Journal of Business Ethics, pp. 413-424, 2019..

A part of research suspects that in response to the profusion of CSR claims, negative external labels could serve as more accurate help to customers in evaluating companies’ environmental performances 132J. Gosselt, T. van Rompay und L. Haske, „Won’t Get Fooled Again: The Effects of Internal and External CSR ECO-Labeling,“ Journal of Business Ethics, pp. 413-424, 2019.. Showcasing the effectiveness of negative front of package labelling is France´s Nutri-Score label. It evaluates a food product on its healthiness and communicates the evaluation on a traffic light like scale. As a result, the customers buying behaviour towards healthy choices improved measurably when comparing against unlabelled products 133E. Finkelstein, F. Ang, B. Doble, W. Wong und R. A. van Dam, „Randomized Controlled Trial Evaluating the Relative Effectiveness of the Multiple Traffic Light and Nutri-Score Front of Package Nutrition Labels.,“ Nutrients, Bd. 11, Nr. 9, p. 2236, 2019..

Although eco-labels are thought to reduce information asymmetry between the producer and the consumer regarding the environmental attributes of a product or service, the lack of credibility or the lack of understanding of eco-labels might lead to consumer confusion or even negative reactions toward eco-labels. This imposes the aforementioned greenwashing effect and dissuades customers from purchasing such products 134M. Delmas, „PERCEPTION OF ECO-LABELS: ORGANIC AND BIODYNAMIC WINES,“ UCLA Institute of the Environment and Anderson School of Management, Los Angeles, CA, 2008. , 135L. Ibanez und G. Grolleau, „Can Ecolabeling Schemes Preserve the Environment?,“ Springer Science + Business Media, Wiesbaden, 2007.. An example for negative effects on the perception of quality is the labelling of Californian wine with an eco-label. Some customers confused the message of the eco-label. Instead of interpreting the label as a sign for organically grown grapes they perceived the label as an indicator for an all-natural production process and therefore lower quality of the wine. This shows the effects of misleading or unclear communication when it comes to labelling, even though unintentional 136M. Delmas und L. Grant, „Eco Labeling Strategies and Price-Premium: the Wine Industry Puzzle,“ Business & Society, Bd. 1, pp. 161-172, 2014..

As a result of customer confusion, the added cost of certifying a product or service and obliging to the standards may exceed the added value from the eco-label certification. This risk needs to be assessed before the implementation as it may deter customers from buying the labelled products and subsequently discourage companies to add eco-labels to their products 137M. Delmas und L. Grant, „Eco Labeling Strategies and Price-Premium: the Wine Industry Puzzle,“ Business & Society, Bd. 1, pp. 161-172, 2014..

4.3 The role of the government

The government also plays an important and supporting role in the context of environmental certifications, as already alluded to. Governments and institutions can decisively promote both sustainable production and sustainable consumption of goods and services through instruments such as eco-labels 138V. Prieto-Sandoval, J. Alfaro, A. Mejía-Villa und M. Ormazabal, „Eco-labels as a multidimensional research topic: trends and opportunities,“ Journal of Cleaner Production, Bd. 135, pp. 806-818, 2016.. From a policy perspective, eco-labels are also instrumental in informing consumers about the environmental aspects of products on the market. 139M. Yokessa und S. Marette, „A Review of Eco-labels and their,“ International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Bd. 13, pp. 119-163, 2019.. The breadth and depth of the dissemination of environmental certifications, as well as their transparency in markets, is in the hands of institutions and governments, among others. This was evident, for example, in the rapid spread of the German government’s Blauer Engel and the EU Ecolabel, presented earlier 140V. Prieto-Sandoval, J. Alfaro, A. Mejía-Villa und M. Ormazabal, „Eco-labels as a multidimensional research topic: trends and opportunities,“ Journal of Cleaner Production, Bd. 135, pp. 806-818, 2016..

In addition, governments can contribute significantly to increased credibility of the eco-label’s environmental attributes by setting the criteria and enforcing certification. Complementing this, the policymaker must determine the number of inspections of foreign and domestic companies, as well as the penalty for violations and how to fund such a policy. Additionally, authorities can prohibit false claims about product characteristics and inspect certification bodies so that the credibility of eco-labels can be maintained. Thus, the credibility of a label can be enhanced by having it mandated, enforced, and also controlled by a public regulatory agency. However, since the government then bears the costs of establishing the eco-label system as well as monitoring compliance by companies, mandatory eco-labels are more expensive for the government than monitoring voluntary eco-label systems. Nevertheless, it may make sense for the government agency to intervene to increase the efficiency of voluntary eco-labelling. Without imposing mandatory measures on companies, it can influence companies’ incentives to adopt a label voluntarily. This includes, for example, the provision of government subsidies 141M. Yokessa und S. Marette, „A Review of Eco-labels and their,“ International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Bd. 13, pp. 119-163, 2019..

Besides that, the government can limit or expand the number of environmental attributes that an eco-label signals, so that the creation of global eco-labels can be supported. General explanations and recommendations about the positive effects of greener consumption can additionally increase consumer knowledge and awareness, although this may not bring about fundamental behavioral change. Moreover, government institutions can regulate the number of eco-labels in the market. This can be done, for example, by limiting the number of eco-labels that an owner may award. Thus, the requirements for introducing new labels would also be increased and a maximum number of eco-labels would be set for certain categories of services and goods. Lastly, the government could force companies to disclose their environmental information so that consumers are better and more comprehensively informed about product characteristics 142M. Yokessa und S. Marette, „A Review of Eco-labels and their,“ International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Bd. 13, pp. 119-163, 2019..

References

- 1Kritika, S. Kaushal und Abhishek, „Eco-labeling: The Influence of Eco-labeld Products on Consumer Buying Behavior,“ Just Agriculture, pp. 1-5, October 2021.

- 2A. De Chiara, „Eco-labeld Products: Trends or Tool for Sustainability Strategies,“ Journal of Business Ethics, pp. 161-172, 2016.

- 3Kritika, S. Kaushal und Abhishek, „Eco-labeling: The Influence of Eco-labeld Products on Consumer Buying Behavior,“ Just Agriculture, pp. 1-5, October 2021.

- 4J. Gosselt, T. van Rompay und L. Haske, „Won’t Get Fooled Again: The Effects of Internal and External CSR ECO-Labeling,“ Journal of Business Ethics, pp. 413-424, 2019.

- 5A. De Chiara, „Eco-labeld Products: Trends or Tool for Sustainability Strategies,“ Journal of Business Ethics, pp. 161-172, 2016.

- 6M. Salman, „Eco Labels: Tools of Green Marketing,“ International Research Journal of Management Sociology & Humanity, Bd. 5, pp. 16-23, 2016.

- 7R. Gertz, „Eco-lanelling – a case for deregulation,“ Law, Probability and Risk, pp. 127-141, 2005.

- 8M. Salman, „Eco Labels: Tools of Green Marketing,“ International Research Journal of Management Sociology & Humanity, Bd. 5, pp. 16-23, 2016.

- 9M. Saal, Eco-Labelling und Länderunterschiede – Voraussetzungen für ein effektives Eco-Label-System, Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH, 2017.

- 10M. Delmas und L. Grant, „Eco Labeling Strategies and Price-Premium: the Wine Industry Puzzle,“ Business & Society, Bd. 1, pp. 161-172, 2014.

- 11R. Gertz, „Eco-lanelling – a case for deregulation,“ Law, Probability and Risk, pp. 127-141, 2005.

- 12F. Iraldo, R. Griesshammer und W. Kahlenborn, „The future of ecolabels,“ The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, Bd. 5, pp. 833-839, 2020.

- 13Lidl Dienstleistung GmbH & Co. KG, „Verantwortung für tierische Produkte,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://unternehmen.lidl.de/verantwortung/handlungsfeld-sortiment/food-sortiment/tierische-produkte. [Zugriff am 28.06.2022].

- 14Lidl Dienstleistung GmbH & Co. KG, „Rund 50 Prozent des Frischfleischsortiments auf Stufe 2 “Stallhaltung plus”,“ [Online]. Available: https://unternehmen.lidl.de/pressreleases/190327_haltungskompass-50-prozent-ziel. [Zugriff am 26.06.2022].

- 15Lidl Dienstleistung GmbH & Co. KG, „Verantwortung für tierische Produkte,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://unternehmen.lidl.de/verantwortung/handlungsfeld-sortiment/food-sortiment/tierische-produkte. [Zugriff am 28.06.2022].

- 16Lidl Dienstleistung GmbH & Co. KG, „Rund 50 Prozent des Frischfleischsortiments auf Stufe 2 “Stallhaltung plus”,“ [Online]. Available: https://unternehmen.lidl.de/pressreleases/190327_haltungskompass-50-prozent-ziel. [Zugriff am 26.06.2022].

- 17Lidl Dienstleistung GmbH & Co. KG, „Verantwortung für tierische Produkte,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://unternehmen.lidl.de/verantwortung/handlungsfeld-sortiment/food-sortiment/tierische-produkte. [Zugriff am 28.06.2022].

- 18F. Iraldo, R. Griesshammer und W. Kahlenborn, „The future of ecolabels,“ The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, Bd. 5, pp. 833-839, 2020.

- 19M. Delmas und L. Grant, „Eco Labeling Strategies and Price-Premium: the Wine Industry Puzzle,“ Business & Society, Bd. 1, pp. 161-172, 2014.

- 20F. Fuerst und P. McAllister, „Eco-labeling in commercial office markets: Do LEED and Energy Star offices obtain multiple premiums?,“ Ecological Economics, pp. 1220-1230, 2011.

- 21A. Gerlach und A. Schudak, „Bewertung ökologischer und sozialer Label zur Förderung eines nachhaltigen Konsums,“ Umweltpsychologie, Bd. 2, pp. 30-40, 2010.

- 22M. Salman, „Eco Labels: Tools of Green Marketing,“ International Research Journal of Management Sociology & Humanity, Bd. 5, pp. 16-23, 2016.

- 23Kritika, S. Kaushal und Abhishek, „Eco-labeling: The Influence of Eco-labeld Products on Consumer Buying Behavior,“ Just Agriculture, pp. 1-5, October 2021.

- 24R. Gertz, „Eco-lanelling – a case for deregulation,“ Law, Probability and Risk, pp. 127-141, 2005.

- 25F. Iraldo, R. Griesshammer und W. Kahlenborn, „The future of ecolabels,“ The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, Bd. 5, pp. 833-839, 2020.

- 26R. Gertz, „Eco-lanelling – a case for deregulation,“ Law, Probability and Risk, pp. 127-141, 2005.

- 27RAL gemeinnützige GmbH, „Umweltzeichen mit Geschichte,“ [Online]. Available: https://www.blauer-engel.de/de/blauer-engel/unser-zeichen-fuer-die-umwelt/umweltzeichen-mit-geschichte. [Zugriff am 19.06.2022].

- 28Umweltmission gUG i. G., „Umweltzeichen: Übersicht und Bedeutung,“ [Online]. Available: https://umweltmission.de/wissen/umweltzeichen/#Der_Blaue_Engel_-_ein_bekanntes_Umweltzeichen. [Zugriff am 19.06.2022].

- 29RAL gemeinnützige gmbH, „Blauer Engel Produkte und Dienstleistungen,“ [Online]. Available: https://eu-ecolabel.de/eu-ecolabel-das-umweltzeichen-ihres-vertrauens/ueber-das-eu-ecolabel. [Zugriff am 28.06.2022].

- 30F. Iraldo, R. Griesshammer und W. Kahlenborn, „The future of ecolabels,“ The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, Bd. 5, pp. 833-839, 2020.

- 31M. Salman, „Eco Labels: Tools of Green Marketing,“ International Research Journal of Management Sociology & Humanity, Bd. 5, pp. 16-23, 2016.

- 32N. Ecolabelling, „The official ecolabel of the Nordic countries,“ [Online]. Available: https://www.nordic-ecolabel.org/nordic-swan-ecolabel/. [Zugriff am 19.06.2022].

- 33Bluesign Technologies AG, „Unsere Vision. Unsere Mission,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.bluesign.com/de/business/unsere-geschichte. [Zugriff am 28.06.2022].

- 34RAL gemeinnützige GmbH, „Über das EU Ecolabel,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://eu-ecolabel.de/eu-ecolabel-das-umweltzeichen-ihres-vertrauens/ueber-das-eu-ecolabel. [Zugriff am 28.06.2022].

- 35E. Commission, „EU Ecolabel,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/circular-economy/eu-ecolabel-home_en. [Zugriff am 28.06.2022].

- 36M. Salman, „Eco Labels: Tools of Green Marketing,“ International Research Journal of Management Sociology & Humanity, Bd. 5, pp. 16-23, 2016.

- 37G. E. Network, „GEN: The Global Ecolabelling Network,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://globalecolabelling.net/about/gen-the-global-ecolabelling-network/. [Zugriff am 28.06.2022].

- 38G. E. Network, „GEN: The Global Ecolabelling Network,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://globalecolabelling.net/about/gen-the-global-ecolabelling-network/. [Zugriff am 28.06.2022].

- 39G. E. Network, „What is Ecolabelling?,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://globalecolabelling.net/what-is-eco-labelling/. [Zugriff am 28.06.2022].

- 40M. Salman, „Eco Labels: Tools of Green Marketing,“ International Research Journal of Management Sociology & Humanity, Bd. 5, pp. 16-23, 2016.

- 41F. Iraldo, R. Griesshammer und W. Kahlenborn, „The future of ecolabels,“ The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, Bd. 5, pp. 833-839, 2020.

- 42M. Salman, „Eco Labels: Tools of Green Marketing,“ International Research Journal of Management Sociology & Humanity, Bd. 5, pp. 16-23, 2016.

- 43Ecolabel Index, „Ecolabel Index,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.ecolabelindex.com/. [Zugriff am 19.06.2022].

- 44F. Iraldo, R. Griesshammer und W. Kahlenborn, „The future of ecolabels,“ The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, Bd. 5, pp. 833-839, 2020.

- 45R. E. Horne, „Limits to labels: The role of eco-labels in the assessment,“ International Journal of Consumer Studies, Bd. 33, pp. 175-182, 2009.

- 46M. Yokessa und S. Marette, „A Review of Eco-labels and their,“ International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Bd. 13, pp. 119-163, 2019.

- 47ISO, „Environmental labels and declarations — Type I environmental labelling — Principles and procedures,“ 1999. [Online]. Available: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:14024:ed-1:v1:en. [Zugriff am 24.06.2022].

- 48R. E. Horne, „Limits to labels: The role of eco-labels in the assessment,“ International Journal of Consumer Studies, Bd. 33, pp. 175-182, 2009.

- 49M. Koszewska, „Social and Eco-labelling of Textile and Clothing Goods as Means of,“ FIBRES & TEXTILES, Bd. 19, Nr. 4 (87), pp. 20-26, 2011.

- 50R. E. Horne, „Limits to labels: The role of eco-labels in the assessment,“ International Journal of Consumer Studies, Bd. 33, pp. 175-182, 2009.

- 51M. Koszewska, „Social and Eco-labelling of Textile and Clothing Goods as Means of,“ FIBRES & TEXTILES, Bd. 19, Nr. 4 (87), pp. 20-26, 2011.

- 52M. Koszewska, „Social and Eco-labelling of Textile and Clothing Goods as Means of,“ FIBRES & TEXTILES, Bd. 19, Nr. 4 (87), pp. 20-26, 2011.

- 53M. Yokessa und S. Marette, „A Review of Eco-labels and their,“ International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Bd. 13, pp. 119-163, 2019.

- 54M. Yokessa und S. Marette, „A Review of Eco-labels and their,“ International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Bd. 13, pp. 119-163, 2019.

- 55RAL gGbmH, „Das deutsche Umweltzeichen,“ 2022a. [Online]. Available: https://www.blauer-engel.de.de. [Zugriff am 17.06.2022].

- 56RAL GmbH, „Was ist das EU Ecolabel?,“ 2022b. [Online]. Available: https://eu-ecolabel.de. [Zugriff am 17.06.2022].

- 57MTP, „Ökologische Siegel und wie sie das Kaufverhalten beeinflussen,“ 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.mtp.org/magazin/2021/03/15/oekologische-siegel-und-wie-sie-das-kaufverhalten-beeinflussen-mtp-e-v. [Zugriff am 18.06.2022].

- 58Utopia GmbH, „Lost in Label? Welchen Siegeln bewusste Konsumenten am meisten vertrauen – Siegel Studie,“ 2019. [Online]. Available: https://i.utopia.de/sales/utopia-siegel-studie-lost-in-label-2019.pdf. [Zugriff am 18.06.2022].

- 59MSC, „Wofür steht das MSC-Siegel?,“ 2022a. [Online]. Available: https://www.msc.org/de/ueber-uns/der-msc. [Zugriff am 18.06.2022].

- 60MSC, „Der MSC,“ 2022b. [Online]. Available: https://www.msc.org/de. [Zugriff am 18.06.2022].

- 61MTP, „Ökologische Siegel und wie sie das Kaufverhalten beeinflussen,“ 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.mtp.org/magazin/2021/03/15/oekologische-siegel-und-wie-sie-das-kaufverhalten-beeinflussen-mtp-e-v. [Zugriff am 18.06.2022].

- 62M. Yokessa und S. Marette, „A Review of Eco-labels and their,“ International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Bd. 13, pp. 119-163, 2019.

- 63FEE, „Our programme,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.blueflag.global/our-programme. [Zugriff am 18.06.2022].

- 64FairWeg GmbH, „Das Green Globe Zertifikat,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://fairweg.de/nachhaltigkeits-zertifikate/green-globe/.. [Zugriff am 18.06.2022].

- 65Green Globe Certification, „The global leader in Sustainable Tourism Certification,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.greenglobe.com/.. [Zugriff am 18.06.2022].

- 66M. Yokessa und S. Marette, „A Review of Eco-labels and their,“ International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Bd. 13, pp. 119-163, 2019.

- 67M. Yokessa und S. Marette, „A Review of Eco-labels and their,“ International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Bd. 13, pp. 119-163, 2019.

- 68Bundesrepublik Deutschland, „EU-Energielabel,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/umwelttipps-fuer-den-alltag/siegelkunde/eu-energielabel. [Zugriff am 19.06.2022].

- 69MTP, „Ökologische Siegel und wie sie das Kaufverhalten beeinflussen,“ 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.mtp.org/magazin/2021/03/15/oekologische-siegel-und-wie-sie-das-kaufverhalten-beeinflussen-mtp-e-v. [Zugriff am 18.06.2022].

- 70Producto GmbH, „Nachhaltigkeitssiegel: Das sind die Guten,“ 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.testberichte.de/magazin/umweltsiegel-und-ihre-bedeutung.html. [Zugriff am 19.06.2022].