Authors: Tom Glaeseker, Jens Holzkämper, Luca Thost, Tammo Resener

Last updated: December 29, 2022

1 Definition and relevance

1.1 Definition

The idea behind the circular economy is to transform the industrial economy into a regenerative system. The approach aims to minimize resource use and waste production, emissions, and energy waste by slowing down, reducing, and closing energy and material cycles. All phases are considered, from material extraction to production and distribution, as well as consumption and subsequent recycling. Products should be designed in such a way that they are as efficient as possible in their use and can be disassembled into components or the raw materials can be recovered at a later point in time. Depending on the quality of the remaining components, they can be incorporated into identical products or processed into lower-quality products (also known as downcycling).1Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

The concept of the circular economy was developed in 1990 by British economist David W. Pearce, building on approaches from industrial ecology, which attempts to put the relationship between nature and society on a permanently sustainable basis. This advocates the minimization of resources and the use of clean technologies. The circular economy aims to minimize the use of the environment as a pollutant sink for waste and the use of materials in manufacturing. Therefore, the natural material cycle is taken as a model and attempts are made to achieve cascading uses reducing waste.2Andersen, Mikael Skou: An introductory note on the environmental economics of the circular economy. Sustainability Science. 2. 133–140 (2006).

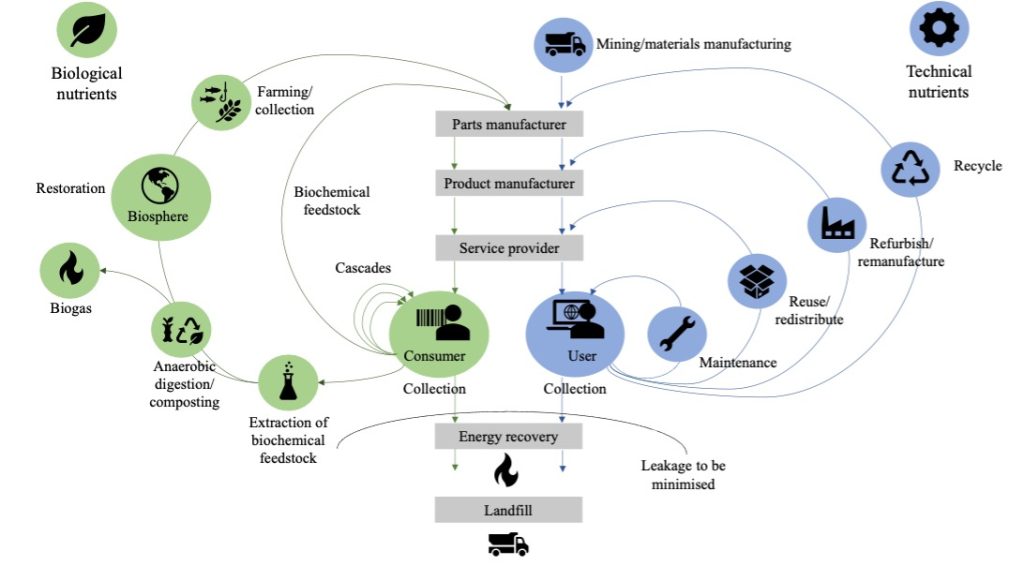

A continuous and consistent circular economy is formulated in the cradle-to-cradle principle by German chemist Michael Braungart and US architect William McDonough. The principle aims at the most complete possible reuse of resources invested. The principle is to return biological nutrients to biological cycles and to keep technical nutrients continuously in technical cycles. The philosophy of nothing goes to landfill is followed. The circular economy approach is described as running the economy as nature runs its own business.3Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

The Figure 1 shows the cycle of biological as well as technical nutrients through the economic system. Biological nutrients from products and materials should be returned to the biosphere via non-toxic, regenerative cycles. Products consisting of technical resources should have an extended life cycle. The first step is to repair and maintain the products if a malfunction occurs. If the user no longer needs this product, it can be passed to another user somewhere else. If possible, the product can be refurbished. When the end of life is reached, the manufacturer dismantles the product into individual parts which can be used in other similar products. When this is not possible the materials of those components can be recycled.4Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

The goal is to cycle valuable metals polymers and alloys, so they maintain their quality and continue to be useful beyond shelf life of individual products. In the context of the circular economy, products and components must be rethought, as well as the packaging in which they come. Goods of today are resources of tomorrow.5Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

However, the circular economy is only one piece of the sustainability puzzle. Other issues that need to be considered include sustainable energy supply, sustainable agriculture, climate change and social sustainability.7Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

1.2 Relevance

More and more companies perceive that the linear system leads to high risks and dependencies. On the one hand, rising prices on increasingly complicated resource markets are a particular reason for this behavior. On the other hand, limited natural resources are another reason. According to forecasts, the future demand for (natural) resources exceeds the real amount available.8Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013)., 9Kranert, M. Einführung in die Kreislaufwirtschaft. (SpringerVieweg, 2018).

In the last decades, the linear economy has been favored by the low-price level of resources compared to labor costs. Eventually, this has led to today’s wasteful system of resource use.

- Energy use: Residual energy is lost through waste in the linear economy. Most energy is lost in upstream production steps, such as the extraction of resources. Recycling can save energy here.10Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- Erosion of ecosystem services: Ecosystem services are benefits derived from the ecosystem for the well-being of humanity, such as forests, provision of food. These services are largely used unsustainably, meaning that more is consumed than is returned by the earth through the natural productivity of ecosystems. One example is deforestation.11Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- Demographic trends: GDP is growing in many countries, especially strongly in Asian countries such as China or India. This means that there is a large and simultaneously increasing demand for resources. One reason for the rising GDP is population growth. According to McKinsey, the population size will level off at 10 billion people by 2100, yet more and more people are entering the middle class and consumer behavior is adapting accordingly.12Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- Infrastructure needs: Due to demographic trends, infrastructure will also have to be further developed. To develop this, high investments would be required to expand new reserves of steel, water, agriculture, and energy. One possible risk is that supply bottlenecks will arise in the long term.13Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- Political risks: Recent events show the impact that political events, such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, can have on commodity production and supplies. In addition to a price increase, there was also a supply shortage. Other political influencing factors can include cartels, subsidies and trade barriers.14Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- Globalized markets: Globalization favors the easy transportation of resources around the world. Short interruptions in supply chains or local events can therefore quickly have a global impact on price stability.15Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- Climate: Water and agriculture are particularly affected by climate variability. Climate changes can affect fresh water supplies and lead to supply shortages, but especially to uncertainties. A large part of the water demand is due to energy production.16Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013)., 17Kranert, M. Einführung in die Kreislaufwirtschaft. (SpringerVieweg, 2018).

Falling resource costs have fueled the economic boom of recent decades at the expense of the disadvantages of the linear economy. To counteract these consequences of the trends, the circular economy must be integrated into business models at an early stage.18Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013)., 19Kranert, M. Einführung in die Kreislaufwirtschaft. (SpringerVieweg, 2018).

2 Background

In the pre-industrial agriculture, the economy was based on self-sufficiency. Efficient use of materials and products was already a major component of economic activity. If we compare consumption today with what it was back then, we can see that per capita material requirements today have increased by a factor of more than five. In the private sector, for example, household waste was used as fertilizer for agricultural land. The repair and recycling of metals, textiles and materials was not only of great importance for private individuals, but also in the commercial sector.20Kranert, M. Einführung in die Kreislaufwirtschaft. (SpringerVieweg, 2018).

Since the mid-19th century, efforts were increased to produce goods and services in large quantities at desirable prices, enabling consumption by the general population. Accordingly, efficiency and rationalization were the decisive factors in production during this period. These conditions were present in the USA, for example. At the same time, the population there grew from 10 million in 1820 to 50 million in 1880 and 90 million in 1910. This was due to the development of agricultural land, which supplied the urban population in addition to the farming population. During this time, characteristics such as longevity were an important indicator for consumer goods.21Kleinschmidt, C. & Logemann, J. Konsum im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert. (Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2021).

This trend continued until the middle of the 20th century, notwithstanding the progress of industrialization and the fact that real wages more than doubled until after World War II. The strong economic growth that began in 1950 used natural resources exponentially. The consumption of oil, metals and natural gas exceeded global population growth significantly. However, it should be noted that the western industrialized countries were largely responsible for the consumption of natural resources during this period.22Kranert, M. Einführung in die Kreislaufwirtschaft. (SpringerVieweg, 2018).

A change in the population’s consumption behaviour could be observed after World War II. The first years were still characterized by scarcity. This situation was gradually changed after about 10 years. The shortages were interrupted and there was a broad expansion of consumption possibilities. Therefore, the individualization and pluralization of consumption can be seen excellently in the 1960s. The reason for this was, on the one hand, the strong economic growth, but also the increase in wages. In addition, social benefits, such as child benefits, have increased, which has also expanded consumption opportunities for lower-income families. Technical developments made household and entertainment goods cheaper and therefore more affordable.23Kleinschmidt, C. & Logemann, J. Konsum im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert. (Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2021).

Despite the growth of prosperity and the advantages that come with it, already in the 60’s there were the first thoughts about how a future with increasing consumption could look like. In 1966 the first concepts about a circular economy were formulated and proposed by Kenneth E. Boulding. He proposed in his “The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth” the idea of a so-called spaceman economy which describes a system with limited resources. “Man must find his place in a cyclical ecological system which is capable of continuous reproduction of material form even though it cannot escape having inputs of energy.” 24Boulding, K. E. The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth. (1966). He further describes the system by saying that production and consumption should not be seen as something good, but rather as something bad. Therefore, instead of increasing production and consumption, we should focus on limited resources. How can resources be used most efficiently and sustainably to ensure a successful economy? 25Boulding, K. E. The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth. (1966).

In 1972, the Club of Rome commissioned the study “Limits to Growth”, led by Dennis Meadows, which concluded that the exponential consumption of natural resources will have a negative impact on global development in the 21st century. This could lead to a decline in the quality of life or even to a decline in population. As a result, the study makes clear that a comprehensive, future-oriented change is necessary. This applies in particular to the use of natural resources, but also to the reduction of CO2 emissions. In 1992, the authors published an update called “Beyond the limits”. They showed that despite the warnings from “limits of growth”, the development has not become more sustainable.26Maedows, D. & Randers, J. & Meadows, D. Grenzen des Wachstums – Das 30-Jahre-Update. (Hirzel Verlag, 2020).

Stahel and Reday-Mulvey also proposed their idea of a circular economy to the European Commission in their 1982 book, “Jobs for Tomorrow, the Potential for Substituting Manpower for Energy”. There they describe how a closed-looped economy can have impact on economic, social and ecologic factors.27Stahel, W. & Reday-Mulvey, G. Jobs for tomorrow: the potential for substituting manpower for energy. (1981). Building on these ideas, the term “cradle to cradle” was later coined by Stahel and Braungart. This was continued by McDonough and Braungart in their joint book “Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way we make Things”.28Braungart, M. & McDonough, W. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way we make Things. (2002).

The term circular economy was further coined in the early 90s by David Pearce and R. Kerry Turner in their book “Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment”.29Pearce, D. W. & Turner, R. K. Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment. (1990). There they describe how to reconcile the relationship between the environment and the economy. With the help of thermodynamics, they make it clear that both systems must be considered together. Lastly, three economic functions could be identified: resource supply, waste assimilator and aesthetic commodity. Aesthetic commodity described as “supplies utility directly in the form of aesthetic enjoyment and spiritual comfort e.g., the pleasure of a fine view.” 30Pearce, D. W. & Turner, R. K. Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment. (1990).

Despite the presentation of various concepts such as the spaceman economy, limits to growth, the cradle-to-cradle approach, or the circular economy, and the additional presentation of resource consumption and pollution, most companies still work according to the take-make-dispose pattern. This is also reflected in the volume of products manufactured, which is estimated at 82 billion tons in 2020.31Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

To counteract this, the German government, for example, has drawn up a Recycling Management Act, which is intended to promote the circular economy. This law came into force on June 1, 2012.32Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, nukleare Sicherheit und Verbraucherschutz. Kreislaufwirtschaftsgesetz. https://www.bmuv.de/gesetz/kreislaufwirtschaftsgesetz#:~:text=Das%20Kreislaufwirtschaftsgesetz%20trat%20am%201,und%20Bewirtschaftung%20von%20Abf%C3%A4llen%20sicherzustellen (2022). Accessed on 15/09/2022. Furthermore, with the 2030 Agenda, the United Nations has set itself the goal of pursuing 17 global goals for sustainable development. This law was passed on September 25, 2015, and subsequently the “Paris Agreement” was adopted at the World Climate Conference in Paris, which was signed by 195 countries.33Auswärtiges Amt. Agenda 2030 für nachhaltige Entwicklung. https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/de/aussenpolitik/themen/agenda2030 (2021). Accessed on 15/09/2022. The Paris Agreement aims to limit the global temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius and to reduce climate-damaging gases to a minimum.34Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung. Klimaabkommen von Paris. https://www.bmz.de/de/service/lexikon/klimaabkommen-von-paris-14602 (2022). Accessed on 15/09/2022.

3 Practical implementation

3.1 Product design

The highest savings potential is possible in the design phase of a product. Decisions are made that significantly influence the later phases. The product structure is determined and the materials for manufacturing are selected. This is followed by questions about the degree to which the components are separated from one another and whether individual components can be replaced. These concerns affect the longevity of the product and therefore the ability to maintain and repair it. Easy disassembly allows the components to be reused in other products and recycled.35Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

Aligning products sustainably has positive economic effects for a company. A sustainable image is becoming increasingly important to sell products and services. This is accompanied by potential cost savings. The reuse of individual components and materials can counteract rising material prices. Natural resources are increasingly being depleted and finding new deposits for mining is becoming more costly. The mining and smelting require a lot of energy. For example, processing recycled copper uses only 10 to 20 % of the energy it takes to process new copper from virgin ore.36Tong, Wang & Berrill, Peter & Zimmerman, Julie & Hertwich, Edgar. Copper Recycling Flow Model for the United States Economy: Impact of Scrap Quality on Potential Energy Benefit. Environmental Science & Technology 55 8, 5485-5495 (2021).

A practical example is the US American company Interface Inc. Interface rents carpeting to other companies as a service.The carpet consists of square shaped parts. If certain areas are worn out, for example by office chairs, Interface can replace them individually. The company offers a line of flooring that is made from 98 % recycled and naturally derived materials.37Clancy, Heather. Interface steps up carpet recycling. GreenBiz. https://www.greenbiz.com/article/interface-steps-carpet-recycling (2016) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

Even household appliances that we use every day are not optimally adapted to their task. Designers are concerned with how to make it technically efficient so that the device consumes little energy and how can green materials be used in its manufacture. Since the products should be used for as long as possible, the use by the customer must also be considered in detail. The neglected consideration of this point is noticeable when using the kettle. The minimum fill line is between two and five cups of water just to make one cup of tea. In 2006 67 % of UK tea drinkers admit to over filling their kettles, when they only need one cup of tea. Since then, the products have not changed much. The difference is often poured away, wasting clean tap water. All this extra boiled water requires energy. It’s been calculated that one day of extra energy use from boiling kettles is enough to light all the streetlights in England for a night. There are also kettles, where the user must push the button to get the water boiled. Because people are lazy, they only fill exactly what they need.38Aldred, Jessica. Tread lightly: Keep your kettle check. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/ethicallivingblog/2008/mar/07/keepyourkettleincheck (2008) Accessed on 15/09/2022. This is a behavior-changing product. Products, systems, or services that intervene and solve these problems upfront.

3.2 Public education

Products we throw away can contribute to climate change regardless that they are made of biodegradable materials. The products should be designed in such a way that they or the individual components can be reused to a high degree. A technique appropriate to the material should be used for disposal. To transition to a circular economy, it is important to educate the public. Equipment that is no longer needed must be passed on to the subsequent re-use and recycling processes to enable the material cycle.39Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

In 2021, Germans alone hoarded 206 million discarded mobile phones at home. An incentive to return defective or old equipment can be helpful in bringing these devices into the recycling process to retrieve minerals such as gold, silver, palladium, and cobalt.40Brandt, Mathias. Deutsche bunkern fast 200 Millionen Alt-Handys. Statista. https://de.statista.com/infografik/13203/anzahl-alt-handys-in-deutschen-haushalten/ (2021) Accessed on 15/09/2022. According to a survey by forsa on behalf of the German Federal Environmental Foundation, most people like the idea of a deposit system for smartphones.41Repräsentative Bevölkerungsbefragung zum Thema “Circular Economy“. Forsa. https://www.dbu.de/media/240621021225bf38.pdf (2021) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

In some areas, typical ownership can be replaced by licensing. For example, a washing machine can be leased by the manufacturer. In this way, the manufacturer remains interested in further economic use. Through his expertise, the manufacturer can adapt his processes to the appliances in the best possible way. He can perform maintenance and repairs on the machine, refurbish it and pass it on to another customer, or reuse and recycle the components and materials.

False environmental folklore must be addressed. One example is the ban on plastic bags. Paper bags seem better for nature at first glance. However, this distinction between good and bad is not so easy to make. Behind the ban on plastic bags is the idea that paper bags are better degraded by nature. When something natural ends up in a natural environment, it degrades normally. The carbon molecules that were absorbed as it grew naturally return to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide. This is a net situation. But most natural things don’t end up in nature. Most of the waste we produce ends up in a landfill. That’s a different environment. In a landfill, the same carbon molecules decompose in a different way because a landfill is anaerobic. It is very compact and hot. The same molecules become methane, and methane is a greenhouse gas 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide. Only modern landfills address this problem and capture methane to generate electricity. In addition, the production of paper bags requires significantly more material, water, and energy. Recycling a pound of plastic requires 91 % less energy than paper.42Edwards, Chris & Fry Jonna: Life cycle assessment of supermarket carrier bags: a review of the bags available in 2006. Environment Agency UK. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/291023/scho0711buan-e-e.pdf (2011) Accessed on 15/09/2022., 43Bell, Kirsty & Cave, Suzie: Comparison of Environmental Impact of Plastic, Paper and Cloth Bags. Northern Ireland Assembly. http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/globalassets/documents/raise/publications/2011/environment/3611.pdf (2011) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

3.3 Implementation methods

The components of a product must be designed in such a way that, for example, technological and biological parts fit into one material cycle. The components should be able to be disassembled and recycled. Biological substances need the property that they are not toxic. Technological substances should be able to be reused with minimal energy input while maintaining the same quality. Recycling, on the other hand, leads to a reduction in quality.44Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013)., 45Kranert, M. Einführung in die Kreislaufwirtschaft. (SpringerVieweg, 2018).

The following practical possibilities arise for the application of the circular economy. These options refer to both, they are implementable by companies as well as private households.46Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013)., 47Kranert, M. Einführung in die Kreislaufwirtschaft. (SpringerVieweg, 2018).

- Material recycling: In recycling, a distinction is made between functional recycling, downcycling and upcycling. Functional recycling means the restoration of materials to their original condition and quality. Downcycling is the transformation of used materials into new materials of lower quality. Upcycling is the opposite: used materials are transformed into new materials of higher quality and possibly a higher range of functions.48Kranert, M. Einführung in die Kreislaufwirtschaft. (SpringerVieweg, 2018).

Furthermore, a distinction is made between primary and secondary recycling in the production processes. Primary recycling refers to the case when materials are already reused within the plant and are recycled. Secondary recycling involves the replacement of raw materials with substances obtained from waste.49Kranert, M. Einführung in die Kreislaufwirtschaft. (SpringerVieweg, 2018).

- Reuse of goods: Reuse of products for the same or similar purpose.50Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- Product refurbishment: Recondition broken or soon to fail products so that they can be used again. This also includes cleaning or painting to renew the appearance of products. In this area, the warranty often applies to the entire product and not to individual parts as in the case of a repair.51Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- Component remanufacturing: From used products to be disposed of, still functioning parts are taken and assembled into a new product. In this way, new products are assembled from used components that are still functioning and still meet the desired quality.52Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- Cascading of components and materials: At the end of their service life, components and materials are ascribed new uses that do not correspond to their original purpose.53Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- Biochemicals extraction: Another practical way to apply the circular economy is using biomass. This can be used to produce high-quality chemical products, such as fuels or chemicals.54Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- Composting: During composting, organic materials are broken down with the help of microorganisms such as bacteria, insects or fungi. This is also referred to as a natural way of recycling.55Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- Anaerobic digestion: Here, too, organic materials are degraded by microorganisms. This produces biogas consisting of methane and carbon dioxide. The resulting substances can be used to generate energy.56Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- Energy recovery: This describes the waste-to-energy processes. In this process, non-recyclable materials are converted into energy. For example, through incineration or gasification.57Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

3.4 Measuring methods

The life cycle assessment is a method for estimating the environmental impact associated with a product or service. It is based on a life cycle approach. This means that the environmental impact of a product is recorded and evaluated from the extraction of the raw materials to the disposal of the product. The intervening steps of production and use are also assessed. Before each analysis, the system limits e. g. “from cradle to grave” or “from cradle to gate” are defined, because different limits make sense depending on the product and the goal of the analysis. The method is highly sensitive to subjective assumptions and system limits. A detailed analysis is very complex and requires a large amount of data. Required information is not always sufficiently available. If use is included, knowledge of usage behavior is necessary. The lack of comparability of different indicators, resources and emission types can be a problem. For example, is CO2 worse than radioactivity. Due to the static approach, typically no rebound effects are considered.58Frischknecht, Rolf. Lehrbuch der Ökobilanzierung (Springer Deutschland, 2020).

3.5 Legal basis

The basic idea can already be found in the European Community Council Directive of 15 July 1975 on waste, which formulated the need to limit the generation of waste and to reuse and recycle waste to preserve raw material and energy sources.59Article 3 and recitals of Directive 75/442/EWG.

The EU has launched the European green deal, which states that by 2050 there will be no more net greenhouse gases, growth is detached from resource use. The EU is pouring 1.8 trillion euros into this.60Europäische Kommission: Mitteilung der Kommission an das Europäische Parlament, den Rat, den Europäischen Wirtschafts- und Sozialausschuss und den Ausschuss der Regionen. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (2020) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

The EU Commission is currently in the process of creating sustainability principles and rules to establish the circular economy. In particular, product groups with a high environmental impact are to be affected, such as electronics, textiles or furniture. Furthermore, products for further processing, such as steel or chemicals, must also be taken into account.61Europäische Kommission: Mitteilung der Kommission an das Europäische Parlament, den Rat, den Europäischen Wirtschafts- und Sozialausschuss und den Ausschuss der Regionen. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (2020) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

To this end, the EU Commission is examining the possibilities of transforming sustainability principles into laws and rules. These include, for example, more sustainable products that are more durable, reusable and repairable. Furthermore, the recycling share is to be increased significantly and become more qualitative. Another component is the further use of digitalization in the production context, for example to create digital product passports.62Europäische Kommission: Mitteilung der Kommission an das Europäische Parlament, den Rat, den Europäischen Wirtschafts- und Sozialausschuss und den Ausschuss der Regionen. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (2020) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- Electronic: Electronics are the fastest growing waste streams and have a low recycling rate. One reason for discarding is, for example, that the product cannot be repaired or that even simple parts, such as the battery, can only be replaced with difficulty. One of the EU’s goals is to use the Ecodesign Directive to make electronic devices such as smartphones and tablets more sustainable. This is to be achieved by increasing energy efficiency and placing emphasis on reusability. In addition, waste electrical and electronic equipment is to be collected through a uniform EU take-back system.63Europäische Kommission: Mitteilung der Kommission an das Europäische Parlament, den Rat, den Europäischen Wirtschafts- und Sozialausschuss und den Ausschuss der Regionen. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (2020) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- Batteries and vehicles: In this area, the EU wants to create regulations on how batteries from vehicles can be collected and recycled.64Europäische Kommission: Mitteilung der Kommission an das Europäische Parlament, den Rat, den Europäischen Wirtschafts- und Sozialausschuss und den Ausschuss der Regionen. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (2020) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- Packaging: The consumption of packaging is increasing annually per inhabitant. The EU wants to eliminate unnecessary packaging and place more emphasis on recyclable and reusable packaging.65Europäische Kommission: Mitteilung der Kommission an das Europäische Parlament, den Rat, den Europäischen Wirtschafts- und Sozialausschuss und den Ausschuss der Regionen. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (2020) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- Plastics: The EU’s goal is to reduce the use of plastic to a minimum and replace it with recycled plastic. In particular, microplastic content is to be reduced. The unintentional release of microplastics is to be better monitored through labelling obligations.66Europäische Kommission: Mitteilung der Kommission an das Europäische Parlament, den Rat, den Europäischen Wirtschafts- und Sozialausschuss und den Ausschuss der Regionen. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (2020) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- Textiles: Only 1 % of the world’s textiles are made from recycled textiles. The EU strategy states that recyclable textiles must be supported more strongly. Moreover, the value lies not only in the product itself but also in the production process used to make the product.67Europäische Kommission: Mitteilung der Kommission an das Europäische Parlament, den Rat, den Europäischen Wirtschafts- und Sozialausschuss und den Ausschuss der Regionen. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (2020) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- Buildings: The construction industry is responsible for a large part of the waste generated. In addition, many raw materials go into buildings and the impact on greenhouse gases is large. In this part, attention will also be paid to building them long-lasting and using sustainable materials.68Europäische Kommission: Mitteilung der Kommission an das Europäische Parlament, den Rat, den Europäischen Wirtschafts- und Sozialausschuss und den Ausschuss der Regionen. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (2020) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- Food: The EU Commission’s goal is to establish the circular economy in the food sector as well. For example, water is to be reused, e.g., for irrigation in agriculture.69Europäische Kommission: Mitteilung der Kommission an das Europäische Parlament, den Rat, den Europäischen Wirtschafts- und Sozialausschuss und den Ausschuss der Regionen. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (2020) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

3.6 Case studies

3.6.1 Patagonia, Inc.

Patagonia, Inc. is an American retailer of outdoor clothing founded in 1973. The founder of Patagonia Yvon Chouinard said that “Patagonia will never be completely socially responsible. It will never make a totally sustainable nondamaging product. But it is committed to trying.” The brand repeatedly calls for more conscious consumption and to buy only things that are really needed. This way, the company hopes to achieve a change in the consumer goods market. The company must balance the environmental priorities upon which Patagonia was founded with its financial well-being. Since 1996, Patagonia has used only organic cotton to eliminate the negative environmental effects of pesticide and fertilizer usage. The brand offers a lifetime product warranty, repair manuals, as well as repair shops. In 2011, the company partnered with eBay, allowing customers to buy and sell used Patagonia clothing on eBay instead of buying it new.70Hoffman, Andrew: Patagonia: Encouraging Customers to Buy Used Clothing. ERB Institute University of Michigan (2012).

With Infinna Fiber, Patagonia aims to create their first circular product. Patagonia T-shirts from their take-back program and used cotton garments from global recycling channels are used to create soft, durable fibers. The cotton garment scraps are recycled into new pulp and then into fiber. When these are mixed with cotton scraps from production that would otherwise end up in landfills, the result is a new T-shirt made from hundred percent recycled materials.71Infinna Fiber. Patagonia. https://eu.patagonia.com/de/de/our-footprint/infinna-fiber.html Accessed on 15/09/2022.

On 14 September 2022, it was announced that founder Chouinard and his family would transfer their ownership of Patagonia to a specially created trust and non-profit organization. The shares are valued at around 3 billion dollars. This is to preserve the company’s independence. All the company’s profits, about $100 million a year, are supposed to be used to fight climate change and protect undeveloped land around the world.72Gelles, David. Patagonia Founder gives away the company to fight climate change. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/14/climate/patagonia-climate-philanthropy-chouinard.html (2022) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

3.6.2 Framework Computer, Inc.

Framework Computer Inc. is a technology startup dedicated to providing a thin, light, powerful notebook that is upgradeable and repairable. The company was founded in 2020 by Nirav Patel, who was previously the head of hardware at Oculus. The Framework laptop was ranked one of the best inventions of 2021 by Times Magazine. The magazine Fast Company listed Framework Computer as an innovative company in 2022. The company wants to reduce electronic waste by making the consumer electronics last longer. Besides external parts like the screen or the keyboard, the battery can be changed, more memory and RAM can be added, or even the mainboard including the CPU can be replaced. Consumers should be able to perform repairs and upgrades themselves. Therefore, the company’s website offers instructions for replacement and repair, as well as a marketplace.73Framework Laptop. https://frame.work Accessed on 15/09/2022., 74Müssig, Florian. Nachhaltig und modular: Framework-Laptop startet in Deutschland. Heise. https://www.heise.de/news/Nachhaltig-und-modular-Framework-Laptop-startet-in-Deutschland-6297975.html (2021) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

4 Drivers and barriers

4.1 Drivers

The circular economy has various drivers, often derived from global trends. The literature shows that these are mainly derived from the categories financial / economic, digitalization, policy and regulatory, market and customer and environmental protection.75Govindan, K. & Hasanagic, M. A systematic review on drivers, barriers, and practices towards circular economy: a supply chain perspective. International Journal of Production Research 56, 278-311 (2018) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

4.1.1 Financial / economic

Literature shows, that one of the key drivers of circular economy is the opportunity to increase wellbeing, growth and to reduce waste. The European Commission estimated that recycling, waste prevention and improved eco-design reduced material consumption between 6 and 12 %. Furthermore, some industries could save up to 23 % material input costs if they produce long living sustainable goods. In 2014 a study came to conclusion that businesses in the EU could safe 245-604 billion euro per year by complying with circular economy policies. In addition, optimizing the waste management and resource efficiency in the European Union could create about 1.3 million jobs. This example of the European Union illustrates how much potential the circular economy has. The chance to increase wellbeing and generate jobs while reducing waste is a fundamental goal for governments. Also as mentioned, businesses profit from implementing circular economy measures. This indicates that the opportunity to increase wellbeing and safe costs is a powerful driver of the circular economy.76Sadhan, K. G. Circular Economy. Global Perspective. (Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd., 2020).

4.1.2 Digitalization

In this context the digitalization may assist companies in their aspiration. There is much potential for automation in many industries, like the textile industry. A study came to conclusion, that digital tools are important for recycling in the textile industry. One example is the possibility to produce 3D printed garments. This technology could be used as an in-store production. Customer customization and printing garments based on 3D technology can reduce the waste, because companies produce their products only if a customer orders one in the store. Besides the reduction of waste and material input, companies can demand higher prices because of the customization.77Sandvik, I. M. & Stubbs, W. Circular fashion supply chain through textile-to-textile recycling. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 23, 366-381 (2019).

A paper of 2018 describes the digitalization as an enabler of circular economy measures by creating new possibilities. By offering product data about condition, location or availability, it can help companies to reduce resource input while using these resources more efficiently. These digital tools can reduce the consumption of energy and calculate the most efficient logistic routes and utilization rates. The RFID-Chip for example offers data about the usage of returned or not working products. This data is important to assess the quality and possibilities to reuse certain parts in a product life cycle management. In addition, digital platforms like online shops improve the distribution of products and services which leads to reduced environmental impact.78Antikainen, M. & Uusitalo, T. & Kivikytö-Reponen, P. Digitalisation as an Enabler of Circular Economy. Procedia CIRP 73, 45-49 (2018).

4.1.3 Policy and regulatory

Legal issues can also be mentioned as a driver for circular economy. The legislation can implement laws to restrict the obtainability for resources for companies. This leads to changing production models because companies must retain the given laws.79De Aguiar Hugo, A. & de Nadae, J. & da Silva Lima, R. Can fashion be circular? A literature review on circular economy. Sustainability 13, (2021). The existing need for action was identified by limits of growth in 1972, as described in chapter 2. Since the situation has not improved until today, the United Nations reacted on the lack of sustainability in 2015. They created 17 sustainable Development Goals called the Agenda 2030 to oppose this. The circular economy is also a fundamental part of this agenda. The primary goals are reducing waste worldwide and encourage sustainable consume and production.80Herlyn, E. & Lévy-Tödter, M. Die Agenda 2030 als Magisches Vieleck der Nachhaltigkeit. (Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH, 2020).

Critics bemoan the required actions to archive these goals are not obligatory. In this way, companies and governments will not change their behavior. The Agenda 2030 shows, that legal issues can be a driver for the circular economy, if goals and needed actions come with obligations. Otherwise, the study limits of growth and the Agenda 2030 just point out need for action and goals, which governments and companies can interpret as they wish.81Drückers, D. Die Agenda 2030: Weniger als das Nötigste. GIGA Focus Global 3, (2017).

4.1.4 Market and customers

Another important driver for circular economy is the growing population as it forces the consumption of resources. Keeping up the way of producing and consuming products in a growing population cannot be sustainable as resources are not renewable in many cases. To stay in the market, companies have to change their production model if they want to keep their business up.82Sandvik, I. M. & Stubbs, W. Circular fashion supply chain through textile-to-textile recycling. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 23, 366-381 (2019). An example of the growing demand is the increasing use of electronic products. In 2000, on average every 100 households in China owned 19.5 cell phones. In 2010 these numbers increased to 188.9 cell phones. This electronic waste is even more difficult to deal with.83Jianguo,Q et al. Developmnent of Circular Economy in China. (Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd., 2016). This example illustrates the increasing demand of resources. Apple, a worldwide distributor of cell phones, has recognized this and implemented a dismantling technology to recycle electronic materials. In 2021, the cell phones were built with 59 % recycled aluminum and 13 % recycled cobalt. Also, Apple sold about 12.2 million refurbished cell phones in 2021.84Apple. Apple setzt in seinen Produkten verstärkt auf recycelte Materialien. https://www.apple.com/de/newsroom/2022/04/apple-expands-the-use-of-recycled-materials-across-its-products/ (2022) Accessed on 15/09/2022. A study of 2021 estimated the cobalt reserves will last for eleven years.85IW Consult GmbH. Rohstoffsituation der bayerischen Wirtschaft (2021). It shows that companies like Apple are forced to recycle these materials in order to stay in the market due to the growing population and demand for resources.

Another driver, which goes hand in hand with the increasing world population and demand for resources, is the consumer’s behavior. The drivers mentioned above all focus on the side of companies, whereas the consumer’s behavior focusses on the market side. The decision to buy circular goods assists the circular economy. Therefore, it is important to gain the acceptance of consumers in order to keep in market with circular goods.86Calvo-Porral, C. & Lévy-Mangin, J.-P. The Circular Economy Business Model: Examining Consumers’ Acceptance of Recycled Goods. Administrative sciences (2020).

Research showed that customers often expect lower quality of recycled products. Therefore, it is important to highlight the environmental benefits of circular products. Customers need to recognize the reduction of waste and the reduction of used energy and natural resources to archive a better image on circular products. This leads to a changing behavior towards an increasing demand for these products, because customers can express their environmental responsibility by purchasing “green products”.87Calvo-Porral, C. & Lévy-Mangin, J.-P. The Circular Economy Business Model: Examining Consumers’ Acceptance of Recycled Goods. Administrative sciences (2020).

4.1.5 Environmental protection

The dependence on natural resources is one of the biggest drivers of climate change. The circular economy, with its ability to recycle products and materials, can help reduce CO2. According to calculations, the implementation of the circular economy in the areas of construction, transport and food production can save approximately 60 % of CO2 emissions by 2050.88Rieg, L. & Meyer, A. & Bertignoll, H. Potentiale der Kreislaufwirtschaft zur Reduktion des Ausstoßes von Treibhausgasen. Berg Hüttenmännische Monatshefte, 169- 172 (2019).

In addition to industry, every individual has impact on the climate change. This means that every human must make their personal behaviour more sustainable. Due to urbanization, cities have to find new ways of reducing waste, resource and energy consumption. This goal can be achieved with the help of circular economy measures, however, citizens’ own responsibility is crucial for the expansion of the circular economy.89Davidescu, A. A. & Apostu, S.-A. & Paul, A. Exploring Citizens´ Actions in Mitigating Climate Change and Moving toward Urban Circular Economy. A Multilevel Approch. Energies 13 (2020).

4.2 Barriers

Besides the drivers of a circular economy, there are also barriers. Barriers can occur in the most diverse areas of the value chain. The literature shows that barriers consist of the following categories technological, cultural / social, financial / economic, policy and regulatory, structural, market and customer.90Kirchherr, J. et al. Barriers to Circular Economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU). Ecological Economics 150, 264-272 (2018).

4.2.1 Technological

One of the most frequently mentioned categories in the literature is technology. However, through the progress of studies it has been found that technology is not the most important factor for companies and policy makers.91Torstensson, L. Internal barriers for moving towards circularity – An industrial perspective. (2016). Nevertheless, there are several barriers that need to be mentioned. Studies show that quality concerns about recycling material, recycled/reused material, and ability to deliver high quality remanufactured products is a key technological barrier. Furthermore, the design of current products does not suit a circular business model. In some cases, these linear product lines are so deeply anchored that integration into the circular economy production process is only possible with great difficulty.92Kirchherr, J. et al. Barriers to Circular Economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU). Ecological Economics 150, 264-272 (2018)., 93IMSA Amsterdam for Circle Economy. Unleashing the Power of the Circular Economy. (2013)., 94Mont, O., Plepys, A., Whalen, K. & Nußholz, J. L.K. Driver and Barriers for the Swedish industry – the voice of REES companies. MISTRA REES. (2017). To enable a change to a circular economy, it is necessary to adapt manufacturing processes (possible processes are described in paragraph 3.3 Implementation methods). However, there are also barriers in the implementation of these processes e.g., disassembling products is hard, work-intense, and expensive also there is a lack of spare parts, repair tools, repair guidelines. It must be ensured that remanufacture/reuse would save energy and resources.95IMSA Amsterdam for Circle Economy. Unleashing the Power of the Circular Economy. (2013).

A study by Steinmann, Huijbregts and Reijnders shows how a material quality indicator can be used to measure the energy consumption of recycled products compared to original products. The focus is only on energy consumption. To create a comprehensive environmental balance, technical, social and economic aspects should also be taken into account.96Steinmann, Z. J. N., Huijbregts, M. A. J. & Reijnders, L. How to define the quality of materials in a circular economy?. Resources, Conversation & Recycling 141, 362-363 (2019). Although, there is a lack of data and examples (large-scale demonstration projects) that could serve as pioneering examples.97Kirchherr, J. et al. Barriers to Circular Economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU). Ecological Economics 150, 264-272 (2018)., 98IMSA Amsterdam for Circle Economy. Unleashing the Power of the Circular Economy. (2013)., 99Mont, O., Plepys, A., Whalen, K. & Nußholz, J. L.K. Driver and Barriers for the Swedish industry – the voice of REES companies. MISTRA REES. (2017). A positive example of a product designed for the circular economy model is the Fairphone. It is based on modern smartphone technology which is integrated into a modular phone. This should allow for easy repair of parts. In addition to the modular approach of the phone, all phones are e-waste neutral. This means that for every phone sold, a phone already on the market or in the trash is recycled.100Fairphone. Nachhaltig. Langlebig. Fair. https://shop.fairphone.com/de/ (2022) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

4.2.2 Cultural / social

One of the most mentioned cultural barriers is the lack of consumer interest, acceptance, and awareness. (Utrecht, Amsterdam, Lund) On the other hand, a 2021 study by Capgemini with around 7800 consumers shows that 79 % of consumers contribute to reducing waste generation by buying better-quality products, maintaining, and repairing products to increase useful product life, and giving away or donating used products.101Capgemini. Circular Economy for sustainable future – How organizations can empower consumers and transition to a circular economy. (2021). The data of Kirchherr, J. et al. was obtained through interviews and surveys with companies and policy makers, which shows that the internal mindset sometimes does not correspond to reality.102Kirchherr, J. et al. Barriers to Circular Economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU). Ecological Economics 150, 264-272 (2018).

Another cultural barrier is the corporate culture, which is described as hesitant and cautious.103Kirchherr, J. et al. Barriers to Circular Economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU). Ecological Economics 150, 264-272 (2018)., 104IMSA Amsterdam for Circle Economy. Unleashing the Power of the Circular Economy. (2013)., 105Mont, O., Plepys, A., Whalen, K. & Nußholz, J. L.K. Driver and Barriers for the Swedish industry – the voice of REES companies. MISTRA REES. (2017)., 106Moors, E. H. M., Mulder, K. F. & Vergragt, P. J. Towards cleaner production: barriers and strategies in the base metals producing industry. Journal of Cleaner Production 13, 657 – 668 (2005)., 107Shi, H., Peng, S., Liu, Y., & Zhong, P. Barriers to the implementation of cleaner production in Chinese SMEs: government, industry and expert stakeholders’ perspectives. Journal of Cleaner Production 16, 842-852 (2008). Managers are risk averse and resilient to change and limited to collaborate in the value chain. This shows that the internal culture of the company is a major obstacle to the adoption of circular economy.108Kirchherr, J. et al. Barriers to Circular Economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU). Ecological Economics 150, 264-272 (2018)., 109IMSA Amsterdam for Circle Economy. Unleashing the Power of the Circular Economy. (2013)., 110Ritzén, S. & Sandström, G. Ö. Barriers to the Circular Economy: integration of perspectives and domains. CIRP 64, 7-12 (2017)., 111Liu, Y., & Bai, Y. An exploration of firms’ awareness and behaviour of developing circular economy: An empirical research in China. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 87, 145-152 (2013). Companies tend not to perceive sustainability properly and have a lack of awareness of circular economy.112Shi, H., Peng, S., Liu, Y., & Zhong, P. Barriers to the implementation of cleaner production in Chinese SMEs: government, industry and expert stakeholders’ perspectives. Journal of Cleaner Production 16, 842-852 (2008)., 113Ritzén, S. & Sandström, G. Ö. Barriers to the Circular Economy: integration of perspectives and domains. CIRP 64, 7-12 (2017). This is also reflected in the different departments. For example, environmental aspects have only a low priority in R&D. The planning department and the production department consist of silos, which makes it difficult to introduce circular economy.114Mont, O., Plepys, A., Whalen, K. & Nußholz, J. L.K. Driver and Barriers for the Swedish industry – the voice of REES companies. MISTRA REES. (2017)., 115Liu, Y., & Bai, Y. An exploration of firms’ awareness and behaviour of developing circular economy: An empirical research in China. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 87, 145-152 (2013).

4.2.3 Financial / economic

Low price of many virgin materials is a barrier, especially when the costs of recycled materials are higher.116Kirchherr, J. et al. Barriers to Circular Economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU). Ecological Economics 150, 264-272 (2018)., 117IMSA Amsterdam for Circle Economy. Unleashing the Power of the Circular Economy. (2013)., 118Mont, O., Plepys, A., Whalen, K. & Nußholz, J. L.K. Driver and Barriers for the Swedish industry – the voice of REES companies. MISTRA REES. (2017). As already described in the technological barriers, there is currently a lack of processes, repair tools and repair guides to disassemble products High investment costs are required to introduce these procedures, tools and guides in the company.119Kirchherr, J. et al. Barriers to Circular Economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU). Ecological Economics 150, 264-272 (2018)., 120Torstensson, L. Internal barriers for moving towards circularity – An industrial perspective. (2016). , 121IMSA Amsterdam for Circle Economy. Unleashing the Power of the Circular Economy. (2013)., 122Mont, O., Plepys, A., Whalen, K. & Nußholz, J. L.K. Driver and Barriers for the Swedish industry – the voice of REES companies. MISTRA REES. (2017)., 123Shi, H., Peng, S., Liu, Y., & Zhong, P. Barriers to the implementation of cleaner production in Chinese SMEs: government, industry and expert stakeholders’ perspectives. Journal of Cleaner Production 16, 842-852 (2008). This potential increase in the cost of capital may lead to a need for financing and thus reduce the overall liquidity of the company’s assets. On the other hand, it is difficult to access funding and if there is access, there only is limited funding.124Kirchherr, J. et al. Barriers to Circular Economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU). Ecological Economics 150, 264-272 (2018)., 125Shi, H., Peng, S., Liu, Y., & Zhong, P. Barriers to the implementation of cleaner production in Chinese SMEs: government, industry and expert stakeholders’ perspectives. Journal of Cleaner Production 16, 842-852 (2008).

Another reason for low cash flow is the product life cycle, which is significantly longer in a circular economy than in a linear value chain.126Torstensson, L. Internal barriers for moving towards circularity – An industrial perspective. (2016). , 127Mont, O., Plepys, A., Whalen, K. & Nußholz, J. L.K. Driver and Barriers for the Swedish industry – the voice of REES companies. MISTRA REES. (2017)., 128Shi, H., Peng, S., Liu, Y., & Zhong, P. Barriers to the implementation of cleaner production in Chinese SMEs: government, industry and expert stakeholders’ perspectives. Journal of Cleaner Production 16, 842-852 (2008)., 129Ritzén, S. & Sandström, G. Ö. Barriers to the Circular Economy: integration of perspectives and domains. CIRP 64, 7-12 (2017). In addition to the high investment costs, there are further internal costs for the management and planning of a circular economy implementation. Furthermore, external ecological costs are not considered.130IMSA Amsterdam for Circle Economy. Unleashing the Power of the Circular Economy. (2013). There is another barrier in the recycling value chain. There is another obstacle in the recycling value chain. A risk exists that repairs, reuses or refurbishments are not cost-efficient. This results from the fact that labour costs are expected to be high when products are dismantled.131Mont, O., Plepys, A., Whalen, K. & Nußholz, J. L.K. Driver and Barriers for the Swedish industry – the voice of REES companies. MISTRA REES. (2017).

4.2.4 Policy and regulatory

In addition to many internal barriers, there are also external barriers, mainly arising from policy and regulations. Since there is a lot of interest in circular economy right now, there are laws and regulations that still hinder the introduction of circular economy. For example, a company is not allowed to transport Bakelite across state borders even though there is a buyer on the other side. Another company is not allowed to use recycled materials in the top layer of tar because it is prohibited by regulations.132Kirchherr, J. et al. Barriers to Circular Economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU). Ecological Economics 150, 264-272 (2018)., 133Torstensson, L. Internal barriers for moving towards circularity – An industrial perspective. (2016). , 134IMSA Amsterdam for Circle Economy. Unleashing the Power of the Circular Economy. (2013). In addition to the hindering laws and regulations, there are also additional laws and regulations that provide an incentive for linear economy, incineration, or disposal. Instead of providing incentives for circular economy.135Torstensson, L. Internal barriers for moving towards circularity – An industrial perspective. (2016). , 136IMSA Amsterdam for Circle Economy. Unleashing the Power of the Circular Economy. (2013)., 137Mont, O., Plepys, A., Whalen, K. & Nußholz, J. L.K. Driver and Barriers for the Swedish industry – the voice of REES companies. MISTRA REES. (2017). As already mentioned in Chapter 2 and 3.5 Legal basis, different committees and laws were created. However, there is a lack of defined targets and government financial incentives for resource efficiency. Furthermore, there is no effective integration of circular economy into innovation policy. And finally, recycling policies are ineffective in achieving high quality recycling.138IMSA Amsterdam for Circle Economy. Unleashing the Power of the Circular Economy. (2013)., 139Mont, O., Plepys, A., Whalen, K. & Nußholz, J. L.K. Driver and Barriers for the Swedish industry – the voice of REES companies. MISTRA REES. (2017).

4.2.5 Structural

Structural barriers run through the entire value chain. The current entanglement of the production system or the dependencies and relationships in the supply chain hinder the circular economy.140Mont, O., Plepys, A., Whalen, K. & Nußholz, J. L.K. Driver and Barriers for the Swedish industry – the voice of REES companies. MISTRA REES. (2017)., 141Shi, H., Peng, S., Liu, Y., & Zhong, P. Barriers to the implementation of cleaner production in Chinese SMEs: government, industry and expert stakeholders’ perspectives. Journal of Cleaner Production 16, 842-852 (2008). Another barrier is the existing confidentiality and trust that prevents the exchange of information.142IMSA Amsterdam for Circle Economy. Unleashing the Power of the Circular Economy. (2013). Time is needed to implement new strategies in a company. The more decentralised a company, the more problems arise. For example, communication gaps, divisions are hard to align and general tension between divisions. Furthermore, limiting the length of employment of managers is another barrier, as it risks the successful implementation of such a comprehensive strategy.143Torstensson, L. Internal barriers for moving towards circularity – An industrial perspective. (2016). , 144Liu, Y., & Bai, Y. An exploration of firms’ awareness and behaviour of developing circular economy: An empirical research in China. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 87, 145-152 (2013). The supplier sector also holds risks. The shift from a linear value chain to a circular value chain creates a structural change between suppliers and producers. One barrier is the lack of networks and/or supply chains for disassembled products and components and recycled materials. Trust needs to be rebuilt with market unstable suppliers. Furthermore, economies of scale can no longer be realised with the new type of suppliers. On the one hand, component manufacturers and other non-OEMs might have limited or unclear opportunities to implement a circular business model due to their position in the value chain. On the other hand, OEMs may risk damaging relationships with their retailers and dealers if they offer repairs or refurbishments.145Torstensson, L. Internal barriers for moving towards circularity – An industrial perspective. (2016). , 146IMSA Amsterdam for Circle Economy. Unleashing the Power of the Circular Economy. (2013)., 147Mont, O., Plepys, A., Whalen, K. & Nußholz, J. L.K. Driver and Barriers for the Swedish industry – the voice of REES companies. MISTRA REES. (2017).

4.2.6 Market and customers

One barrier already mentioned in the cultural barriers is the lack of acceptance of products by customers and the low priority given to products with environmental aspects. This can also be justified by the fact that customers lack awareness of refurbishment, reuse and maintenance.148Mont, O., Plepys, A., Whalen, K. & Nußholz, J. L.K. Driver and Barriers for the Swedish industry – the voice of REES companies. MISTRA REES. (2017)., 149Ghisellini, P., Cialani, C., & Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: the expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. Journal of Cleaner Production 114, 11-32 (2015). Another customer barrier is the quality assurance of refurbished products. Customers fear that refurbished products are inferior to new products.150Torstensson, L. Internal barriers for moving towards circularity – An industrial perspective. (2016). , 151Mont, O., Plepys, A., Whalen, K. & Nußholz, J. L.K. Driver and Barriers for the Swedish industry – the voice of REES companies. MISTRA REES. (2017). In addition, customers show a resistance to leasing. Most customers are not clear how the concepts of leasing work and are therefore hesitant to change their behavior.152Torstensson, L. Internal barriers for moving towards circularity – An industrial perspective. (2016). , 153Capgemini. Circular Economy for sustainable future – How organizations can empower consumers and transition to a circular economy. (2021). In addition to customer barriers, there are other barriers in the market sector. For example, one barrier is that systems for taking back products do not exist. Furthermore, it must be considered that products have a maximum technical reusability.154Torstensson, L. Internal barriers for moving towards circularity – An industrial perspective. (2016). , 155Ghisellini, P., Cialani, C., & Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: the expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. Journal of Cleaner Production 114, 11-32 (2015).

References

- 1Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 2Andersen, Mikael Skou: An introductory note on the environmental economics of the circular economy. Sustainability Science. 2. 133–140 (2006).

- 3Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 4Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 5Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 6Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 7Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 8Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 9Kranert, M. Einführung in die Kreislaufwirtschaft. (SpringerVieweg, 2018).

- 10Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 11Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 12Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 13Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 14Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 15Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 16Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 17Kranert, M. Einführung in die Kreislaufwirtschaft. (SpringerVieweg, 2018).

- 18Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 19Kranert, M. Einführung in die Kreislaufwirtschaft. (SpringerVieweg, 2018).

- 20Kranert, M. Einführung in die Kreislaufwirtschaft. (SpringerVieweg, 2018).

- 21Kleinschmidt, C. & Logemann, J. Konsum im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert. (Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2021).

- 22Kranert, M. Einführung in die Kreislaufwirtschaft. (SpringerVieweg, 2018).

- 23Kleinschmidt, C. & Logemann, J. Konsum im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert. (Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2021).

- 24Boulding, K. E. The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth. (1966).

- 25Boulding, K. E. The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth. (1966).

- 26Maedows, D. & Randers, J. & Meadows, D. Grenzen des Wachstums – Das 30-Jahre-Update. (Hirzel Verlag, 2020).

- 27Stahel, W. & Reday-Mulvey, G. Jobs for tomorrow: the potential for substituting manpower for energy. (1981).

- 28Braungart, M. & McDonough, W. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way we make Things. (2002).

- 29Pearce, D. W. & Turner, R. K. Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment. (1990).

- 30Pearce, D. W. & Turner, R. K. Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment. (1990).

- 31Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 32Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, nukleare Sicherheit und Verbraucherschutz. Kreislaufwirtschaftsgesetz. https://www.bmuv.de/gesetz/kreislaufwirtschaftsgesetz#:~:text=Das%20Kreislaufwirtschaftsgesetz%20trat%20am%201,und%20Bewirtschaftung%20von%20Abf%C3%A4llen%20sicherzustellen (2022). Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 33Auswärtiges Amt. Agenda 2030 für nachhaltige Entwicklung. https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/de/aussenpolitik/themen/agenda2030 (2021). Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 34Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung. Klimaabkommen von Paris. https://www.bmz.de/de/service/lexikon/klimaabkommen-von-paris-14602 (2022). Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 35Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 36Tong, Wang & Berrill, Peter & Zimmerman, Julie & Hertwich, Edgar. Copper Recycling Flow Model for the United States Economy: Impact of Scrap Quality on Potential Energy Benefit. Environmental Science & Technology 55 8, 5485-5495 (2021).

- 37Clancy, Heather. Interface steps up carpet recycling. GreenBiz. https://www.greenbiz.com/article/interface-steps-carpet-recycling (2016) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 38Aldred, Jessica. Tread lightly: Keep your kettle check. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/ethicallivingblog/2008/mar/07/keepyourkettleincheck (2008) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 39Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 40Brandt, Mathias. Deutsche bunkern fast 200 Millionen Alt-Handys. Statista. https://de.statista.com/infografik/13203/anzahl-alt-handys-in-deutschen-haushalten/ (2021) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 41Repräsentative Bevölkerungsbefragung zum Thema “Circular Economy“. Forsa. https://www.dbu.de/media/240621021225bf38.pdf (2021) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 42Edwards, Chris & Fry Jonna: Life cycle assessment of supermarket carrier bags: a review of the bags available in 2006. Environment Agency UK. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/291023/scho0711buan-e-e.pdf (2011) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 43Bell, Kirsty & Cave, Suzie: Comparison of Environmental Impact of Plastic, Paper and Cloth Bags. Northern Ireland Assembly. http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/globalassets/documents/raise/publications/2011/environment/3611.pdf (2011) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 44Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 45Kranert, M. Einführung in die Kreislaufwirtschaft. (SpringerVieweg, 2018).

- 46Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 47Kranert, M. Einführung in die Kreislaufwirtschaft. (SpringerVieweg, 2018).

- 48Kranert, M. Einführung in die Kreislaufwirtschaft. (SpringerVieweg, 2018).

- 49Kranert, M. Einführung in die Kreislaufwirtschaft. (SpringerVieweg, 2018).

- 50Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 51Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 52Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 53Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 54Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 55Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 56Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 57Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Towards the Circular Economy 1: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (2013).

- 58Frischknecht, Rolf. Lehrbuch der Ökobilanzierung (Springer Deutschland, 2020).

- 59Article 3 and recitals of Directive 75/442/EWG.

- 60Europäische Kommission: Mitteilung der Kommission an das Europäische Parlament, den Rat, den Europäischen Wirtschafts- und Sozialausschuss und den Ausschuss der Regionen. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (2020) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 61Europäische Kommission: Mitteilung der Kommission an das Europäische Parlament, den Rat, den Europäischen Wirtschafts- und Sozialausschuss und den Ausschuss der Regionen. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (2020) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 62Europäische Kommission: Mitteilung der Kommission an das Europäische Parlament, den Rat, den Europäischen Wirtschafts- und Sozialausschuss und den Ausschuss der Regionen. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (2020) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 63Europäische Kommission: Mitteilung der Kommission an das Europäische Parlament, den Rat, den Europäischen Wirtschafts- und Sozialausschuss und den Ausschuss der Regionen. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (2020) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 64Europäische Kommission: Mitteilung der Kommission an das Europäische Parlament, den Rat, den Europäischen Wirtschafts- und Sozialausschuss und den Ausschuss der Regionen. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (2020) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 65Europäische Kommission: Mitteilung der Kommission an das Europäische Parlament, den Rat, den Europäischen Wirtschafts- und Sozialausschuss und den Ausschuss der Regionen. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (2020) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 66Europäische Kommission: Mitteilung der Kommission an das Europäische Parlament, den Rat, den Europäischen Wirtschafts- und Sozialausschuss und den Ausschuss der Regionen. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (2020) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 67Europäische Kommission: Mitteilung der Kommission an das Europäische Parlament, den Rat, den Europäischen Wirtschafts- und Sozialausschuss und den Ausschuss der Regionen. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (2020) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 68Europäische Kommission: Mitteilung der Kommission an das Europäische Parlament, den Rat, den Europäischen Wirtschafts- und Sozialausschuss und den Ausschuss der Regionen. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (2020) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 69Europäische Kommission: Mitteilung der Kommission an das Europäische Parlament, den Rat, den Europäischen Wirtschafts- und Sozialausschuss und den Ausschuss der Regionen. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (2020) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 70Hoffman, Andrew: Patagonia: Encouraging Customers to Buy Used Clothing. ERB Institute University of Michigan (2012).

- 71Infinna Fiber. Patagonia. https://eu.patagonia.com/de/de/our-footprint/infinna-fiber.html Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 72Gelles, David. Patagonia Founder gives away the company to fight climate change. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/14/climate/patagonia-climate-philanthropy-chouinard.html (2022) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 73Framework Laptop. https://frame.work Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 74Müssig, Florian. Nachhaltig und modular: Framework-Laptop startet in Deutschland. Heise. https://www.heise.de/news/Nachhaltig-und-modular-Framework-Laptop-startet-in-Deutschland-6297975.html (2021) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 75Govindan, K. & Hasanagic, M. A systematic review on drivers, barriers, and practices towards circular economy: a supply chain perspective. International Journal of Production Research 56, 278-311 (2018) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 76Sadhan, K. G. Circular Economy. Global Perspective. (Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd., 2020).

- 77Sandvik, I. M. & Stubbs, W. Circular fashion supply chain through textile-to-textile recycling. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 23, 366-381 (2019).

- 78Antikainen, M. & Uusitalo, T. & Kivikytö-Reponen, P. Digitalisation as an Enabler of Circular Economy. Procedia CIRP 73, 45-49 (2018).

- 79De Aguiar Hugo, A. & de Nadae, J. & da Silva Lima, R. Can fashion be circular? A literature review on circular economy. Sustainability 13, (2021).

- 80Herlyn, E. & Lévy-Tödter, M. Die Agenda 2030 als Magisches Vieleck der Nachhaltigkeit. (Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH, 2020).

- 81Drückers, D. Die Agenda 2030: Weniger als das Nötigste. GIGA Focus Global 3, (2017).

- 82Sandvik, I. M. & Stubbs, W. Circular fashion supply chain through textile-to-textile recycling. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 23, 366-381 (2019).

- 83Jianguo,Q et al. Developmnent of Circular Economy in China. (Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd., 2016).

- 84Apple. Apple setzt in seinen Produkten verstärkt auf recycelte Materialien. https://www.apple.com/de/newsroom/2022/04/apple-expands-the-use-of-recycled-materials-across-its-products/ (2022) Accessed on 15/09/2022.

- 85IW Consult GmbH. Rohstoffsituation der bayerischen Wirtschaft (2021).

- 86Calvo-Porral, C. & Lévy-Mangin, J.-P. The Circular Economy Business Model: Examining Consumers’ Acceptance of Recycled Goods. Administrative sciences (2020).

- 87Calvo-Porral, C. & Lévy-Mangin, J.-P. The Circular Economy Business Model: Examining Consumers’ Acceptance of Recycled Goods. Administrative sciences (2020).