Authors: Anna-Lena Blanchard, Laura Heckmann, Deniz Öztürk, Katrin Unruh

Last updated: June 22, 2022

1 Definition

Sustainability marketing can be defined as the process of creating, communicating and delivering value to customers that maintains or enhances both natural and human capital throughout.1 Belz, F. M. & Peattie, K. (2012). Sustainability Marketing: A global perspective. 2nd Ed.Chichester: Wiley. This involves building and maintaining sustainable relationships with customers, the social environment and the natural environment.2 Belz, F. M. & Peattie, K. (2010). Sustainability Marketing: An Innovative Conception of Marketing. Marketing Review St Gallen, 27, 8-15.

Sustainability marketing was originally developed from the concepts of ecological and social marketing. Over time, ecological marketing evolved into green marketing, which dealt with far-reaching environmental issues. Social and moral aspects were also taken up in the concept of greener marketing. This eventually developed into sustainable marketing, i.e., marketing within the framework of and in support of sustainable economic development. Here, long-term customer relationships are also effectively established, but in contrast to sustainability marketing, no major reference is made to sustainable development or the consideration of sustainability issues.3 Kumar, V., Rahman, Z. & Kazmi A. A. (2013). Sustainability Marketing Strategy: An Analysis of Recent Literature. Global Business Review, 14, 601–625. However, this term should not be confused with corporate social responsibility (CSR), which can be defined as a concept that provides a basis for companies to voluntarily integrate social and environmental concerns into their corporate activities and interactions with stakeholders. Thus, today’s social and societal aspects are placed in the foreground, and the economic perspective tends to be neglected.4 Kenning, P. (2014). Sustainable Marketing – Definition und begriffliche Abgrenzung. In Balzer, N. (2020). Konsumverhalten. Was motiviert zum Kauf nachhaltiger Lebensmittel?. GRIN Verlag. Ultimately, it can be deduced that all of the above concepts have merged into one another, resulting in sustainability marketing, which includes economic, social and ecological dimensions.3 Kumar, V., Rahman, Z. & Kazmi A. A. (2013). Sustainability Marketing Strategy: An Analysis of Recent Literature. Global Business Review, 14, 601–625.

Basically, the topic of sustainability has become a central requirement for companies in the economy. The concept of marketing must not be limited to intrapersonal and interpersonal needs but extended to the needs of future generations. This must be accompanied by the creation, communication and delivery of customer value based on sustainability.5 Kumar, V., Rahman, Z., Kazmi A. A. & Goyal, P. (2012). Evolution of sustainability as marketing strategy: Beginning of new era. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 37, 482 – 489. In this context, sustainability marketing, which has developed from social and ecological marketing, should be mentioned. This concept can be seen as part of corporate management, which strives for the guiding principle of sustainable development through sustainable management.6 Griese, K. M. (2015). Nachhaltigkeitsmarketing – Eine fallstudienbasierte Einführung. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien. Nevertheless, the transition to sustainability marketing requires innovative thinking in the four core areas described below. To implement this successfully in the company, socioecological challenges must be seen as the starting point of the marketing process. Consumer behavior must also be understood holistically, and the marketing mix needs to be readjusted and redesigned. Finally, the transformation potential of marketing activities and marketing relationships must be recognized and meaningfully used.2 Belz, F. M. & Peattie, K. (2010). Sustainability Marketing: An Innovative Conception of Marketing. Marketing Review St Gallen, 27, 8-15.

Sustainability marketing is an environmentally and socially oriented corporate management in which all operational marketing decisions are directed toward value creation. These values include economic values, such as increased profit or sales, and ecological values, such as the more efficient use of resources. Socially oriented values must not be disregarded, as they represent, for example, the fair payment of employees or suppliers. Alignment with these values takes place through orientation to market requirements, competitive conditions and the observance of ecological and social standards. If a company does not create direct or indirect value, it should at least avoid economic, ecological or social damage.6 Griese, K. M. (2015). Nachhaltigkeitsmarketing – Eine fallstudienbasierte Einführung. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien. In a broader sense, it can also be said that sustainability marketing strategies involve the inclusion of sustainability in strategic marketing and in the marketing mix.2 Belz, F. M. & Peattie, K. (2010). Sustainability Marketing: An Innovative Conception of Marketing. Marketing Review St Gallen, 27, 8-15. The goal is to achieve lasting competitive advantages and to create a credible identity through the interaction of employees and market players, as well as to develop sustainable product or solution innovations.7 Leimböck, E. (2017). Nachhaltigkeitsmarketing. In E. Leimböck, A. Iding & H. Meinen (Eds). Bauwirtschaft (pp. 587-590). Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

2 Sustainability impact and key performance indicators

Sustainability marketing capitalizes on the growing environmental awareness of consumers 8Umweltbundesamt. (2023). Umweltbewusstsein in Deutschland 2022. Berlin. https://www.bmuv.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Pools/Broschueren/umweltbewusstsein_2022_bf.pdf. However, many marketing strategies, often disguised as greenwashing, prioritize growth over sufficiency goals 9Marcinak, A. (2009). Greenwashing as an Example of Ecological Marketing Misleading Practices, Comparative Economic Research. Central and Eastern Europe, ISSN 2082-6737, Łódź University Press, Łódź, Vol. 12, Iss. 1-2, pp. 49-59, https://doi.org/10.2478/v10103-009-0003-x. Sustainability marketing is intricately linked to environmental behavior, which is shaped by internal factors (such as attitudes, intentions and values) and external factors (such as pricing and infrastructure). 10 Islam, Q., & Ali Khan, S.M.F. (2024). Assessing Consumer Behavior in Sustainable Product Markets: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach with Partial Least Squares Analysis. Sustainability, 16, 3400. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16083400 Early approaches have experimented with sufficiency-oriented marketing practices, rethinking business models and promoting transformative initiatives, as demonstrated by Nokia. Nokia launched global consumer campaigns and set up recycling points in all its care centers and priority dealer stores, allowing customers to dispose of unwanted phones and receive discounts on their next purchase. This example illustrates how a holistic approach to sustainability can reduce negative environmental and social impacts while increasing economic benefits for both buyers and sellers. Another notable example is IKEA. IKEA’s sustainability efforts include eliminating polyvinyl chloride (PVC) from almost all its products, increasing the use of energy-efficient light bulbs and promoting recycling. For example, IKEA offered store gift vouchers to customers who returned Christmas trees for recycling, whether purchased from IKEA or another retailer. This initiative not only encouraged consumers to reduce waste, but also reinforced the company’s commitment to environmental protection. Such examples show that sustainability is increasingly recognized as a viable marketing strategy that can influence consumer behavior. By adopting sustainable practices, companies can position themselves positively in the minds of consumers, often as ‘heroes’ contributing to environmental protection. In these cases, the concept of sustainability becomes highly marketable, driven largely by marketing efforts that shape or respond to consumer perceptions and demands. 11 Lim, W. M. (2016). A blueprint for sustainability marketing: Defining its conceptual boundaries for progress. Marketing Theory, 16(2), 232-249.

Another example is the retailer Marks and Spencer, which planned to work with customers and suppliers to fight climate change, reduce waste, protect natural resources, act ethically and build a healthier nation. Regular press releases and informational talks are reinforced by signage and brochures in the company’s stores and window displays. They started a campaign to help children in Uganda attend school, launched a new organic fashion line, removed additives from foods and gave details of a campaign to help customers reduce their footprint.12 Jones, P., Clarke-Hill, C., Comfort, D. & Hillier, D. (2007). Marketing and sustainability. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 26(2), 123-130.

Marketing recognizes the main role of customers as decision-makers in moving toward sustainability through means such as reducing carbon emissions, recycling increasing amounts of waste, supporting fair trade initiatives and adopting healthier lifestyles.9 Jones, P., Clarke-Hill, C., Comfort, D. & Hillier, D. (2007). Marketing and sustainability. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 26(2), 123-130.

Packaging is important for understanding the company and the brand. That is why sustainability should be communicated to consumers, as they expect companies to be sensitive to environmental issues and take on social responsibility. Consumers buy products from companies that exhibit strong sustainability, regardless of the price.13 Kiygi-Calli, M. (2019). Corporate Social Responsibility in Packaging: Environmental and Social Issues. In I. Altinbasak-Farina & S. Burnaz (Eds.). Ethics, Social Responsibility and Sustainability in Marketing (pp. 129-145). Singapore: Springer. The ongoing satisfaction of the customer is of great importance, especially because the perspective is changing from selling products to selling benefits. It is the continuous provision of a benefit, such as mobility or cleanliness, that creates the conditions for longer-term exchange. The opinions of customers finally become relevant in the post-purchase phase. Complaints, suggestions for improvement or expressed satisfaction create starting points for further optimization, profiling and relationship management.14 Spiller, A., Zühlsdorf, A., Schaltegger, S. & Petersen, H. (2007). Nachhaltigkeitsmarketing I: Grundlagen, Herausforderungen und Strategien.

Because sustainability marketing is still relatively new and has not yet been applied everywhere, there are still no KPIs that can be used to measure sustainability in this area. For this reason, the following section will mainly focus on KPIs from traditional and digital marketing and analyze how these can be applied in sustainability marketing. It is important to use KPIs because they can reveal many opportunities for companies.

When sustainability marketing is used, companies actually see a higher conversion rate.11 Spiller, A., Zühlsdorf, A., Schaltegger, S. & Petersen, H. (2007). Nachhaltigkeitsmarke-ting I: Grundlagen, Herausforderungen und Strategien. This value records the connection between visitors on a website and the purchases or interactions made. As a rule, a period of either 24 hours or a maximum of one week is recorded from the first contact.15 Steiger, S. C. (2017). KPIs – Kennzahlen: Wahl und Auswertung der richtigen Parameter. In H. Scholz (Ed.), Social goes Mobile – Kunden gezielt erreichen (2nd ed., pp. 211-227). Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler. In general, it is about focusing on the long-term ROI of a consumer who loves the brand and its products, not the short-term ROI of a quick sale.16 Roberts, M. (2018). What is sustainability marketing? Retrieved on 29/07/2021: https://www.consciouscreatives.co.uk/planning/what-is-sustainability-marketing/. The ROI describes how much revenue was generated in relation to the budget used for a particular action. A simple calculation example is presented as follows: with an investment of €1,000 and a generated turnover of €10,000, the ROI is 10 (€10,000/€1,000), which is quite respectable. In practice, the biggest challenge in calculating the ROI is correctly allocating investment costs and profits to each other. If the allocation is inaccurate or incorrect, there is a risk of arriving at the wrong conclusions regarding the profitability of a particular campaign or digital marketing channel.17 Meier, S. (2018). Kennzahlen im digitalen Marketing. Frankfurt am Main: Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels e.V.

Another important KPI is the cost per acquisition (CPA). These are all costs incurred in connection with customer interaction and in promoting and providing ongoing support for the mobile offering, which are included in the acquisition costs. These involve expenses such as costs for advertising in app store marketing campaigns on other channels and social media support. These can be calculated separately based on the conversion rate per medium.12 Steiger, S. C. (2017). KPIs – Kennzahlen: Wahl und Auswertung der richtigen Parameter. In H. Scholz (Ed.), Social goes Mobile – Kunden gezielt erreichen (2nd ed., pp. 211-227). Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler. Cost per lead (CPL) is an indicator of advertising success intended to place various advertising campaigns on a comparable basis. It evaluates the success of marketing campaigns not on the basis of the sales achieved, but on the basis of the number of interested parties who obtain more detailed information about a product.14 Meier, S. (2018). Kennzahlen im digitalen Marketing. Frankfurt am Main: Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels e.V. Reach—both paid and organic—refers to how many people have seen content on particular days and how many interactions are performed. Cost per mille (CPM) is the price for 1,000 impressions of the ad unit. Display advertising is usually sold on a CPM basis.14 Meier, S. (2018). Kennzahlen im digitalen Marketing. Frankfurt am Main: Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels e.V. Last, the customer lifetime value (CLV) represents the average value that a customer has for a company during their entire “customer life cycle” and is expected to have in the future as well.18 Elsässer, M. (2020). Moderne Marketing-KPIs mit echtem Mehrwert – wie funktioniert’s?. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://www.pwc.de/de/im-fokus/customer-centric-transformation/marketing-advisory/moderne-marketing-kpis-mit-echtem-mehrwert-wie-funktionierts.html.

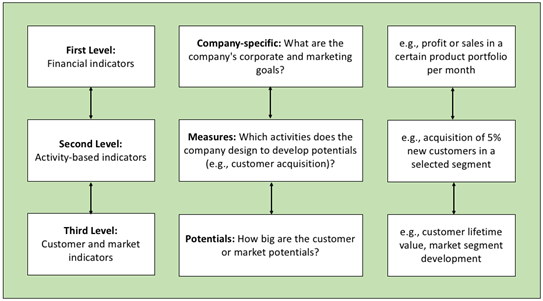

In the economic context of sustainability marketing, for example, metrics can be evaluated on three levels based on task (see Figure 1). At the first level, these are formal economic indicators used to determine the final financial results of the company. These include profit, sales or security indicators such as the liquidity rate. At the second level, activity-related indicators are relevant and can be used to evaluate specific core tasks performed by a company. Classic core tasks are customer acquisition, customer loyalty measures or service innovations and maintenance. The way these core tasks are dealt with reflects part of the strategy in sustainability marketing. If the tasks are handled successfully, this has an influence on the financial results (e.g., growing sales through new customers). The third level covers customer and market indicators for sustainability marketing. These indicators take into account the potential that a company has on the market or with customers. One example is customer lifetime value. This value reflects the contribution margin that a customer will realize over their entire lifetime. Market indicators refer primarily to the development or size of a market segment.6 Griese, K. M. (2015). Nachhaltigkeitsmarketing – Eine fallstudienbasierte Einführung. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien

An example of an environmental KPI is the percentage of recycled material.19 Hristov, I. & Chirico, A. (2019). The Role of Sustainability Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) in Implementing Sustainable Strategies. Sustainability, 11(20), 1-19. This is measured by the recycled packaging used. Another KPI is waste reduction, which is measured by the percentage of waste generated per thousand product units16 Hristov, I. & Chirico, A. (2019). The Role of Sustainability Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) in Implementing Sustainable Strategies. Sustainability, 11(20), 1-19. and can be reduced by campaigns such as the one of IKEA.

Considering the social view, KPIs such as net promoter score (NPS), interaction rate and returning customers are used. The NPS is a key indicator that indirectly quantifies customer satisfaction and directly quantifies willingness to recommend a product or service to others. The advantage of the NPS is its simplicity, while a disadvantage is the fact that it does not provide any well-founded qualified statements as to why someone is dissatisfied or satisfied with a product, service or company. For a quick and uncomplicated satisfaction survey, the NPS is definitely useful. The basic question is: “How likely is it that you will recommend company/brand X to a friend or colleague?” This can be rated on a scale of 0–10, with 10 being the highest value for recommendation (see Figure 2). Customers who answer with 9 or 10 are classified into the first group, called Promoters. This means that it is very likely that they are satisfied and will recommend the company to others. The second group is comprised of the Passives. This group includes customers who answer the first question with 7 or 8. The third group includes all customers who give a 0 to 6. All of these participants belong to the Detractors.14 Meier, S. (2018). Kennzahlen im digitalen Marketing. Frankfurt am Main: Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels e.V.

In the end, the relative proportion of promoters and detractors was calculated using the following formula:

Number of promoters or detractors/number of respondents * 100

The difference between the relative proportions of promoters and detractors gives the net promoter score, which is given as a percentage. With the use of this value, other products or services can now be compared with each other. Another KPI that is part of the social aspect is the interaction rate. It is used to determine the percentage of interactions per impression of the ad unit. This works for ads that can be interacted with through likes, comments or shares, for example.14 Meier, S. (2018). Kennzahlen im digitalen Marketing. Frankfurt am Main: Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels e.V. The concept of returning visitors is clear from the name. This is the key indicator for returning visitors.12 Steiger, S. C. (2017). KPIs – Kennzahlen: Wahl und Auswertung der richtigen Parameter. In H. Scholz (Ed.), Social goes Mobile – Kunden gezielt erreichen (2nd ed., pp. 211-227). Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler. Social KPIs also include the integration rate, stakeholder satisfaction rate, employee satisfaction rate and customer satisfaction rate. All but customer satisfaction rate can be measured by using a questionnaire. The customer satisfaction rate can be measured with a cost analysis.16 Hristov, I. & Chirico, A. (2019). The Role of Sustainability Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) in Implementing Sustainable Strategies. Sustainability, 11(20), 1-19. The source of some KPIs (mostly the ones from websites) is Google Analytics, but a CRM system and questionnaires can also serve as good sources.20 Theobald, E. (2019). Marketingerfolge messbar und sichtbar machen mit KPIs und Dashboards. Management Monitor.

KPIs have pros and cons, and in regard to sustainability, it is important to have a look at the long-term and the inclusion of the three perspectives (social, environmental and economic). Using quality measures such as cost per lead or cost per acquisition increases the lifetime customer value. It helps to listen to customers and focus on creating long-term relationships. This kind of KPI is better than metrics like reach or cost per mille.13 Roberts, M. (2018). What is sustainability marketing? Retrieved on 29/07/2021: https://www.consciouscreatives.co.uk/planning/what-is-sustainability-marketing/. Overall, more customer-centered KPIs and fewer financial metrics should be used. Many companies have already recognized and implemented this. Customer-centered KPIs can be used to measure how well a company is pursuing its defined customer-oriented goals. Examples of such KPIs are brand awareness, website engagement and click-through rate (CTR).15 Elsässer, M. (2020). Moderne Marketing-KPIs mit echtem Mehrwert – wie funktio-niert’s?. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://www.pwc.de/de/im-fokus/customer-centric-transformation/marketing-advisory/moderne-marketing-kpis-mit-echtem-mehrwert-wie-funktionierts.html. CTR is the number of clicks generated per impression of a banner ad.14 Meier, S. (2018). Kennzahlen im digitalen Marketing. Frankfurt am Main: Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels e.V. Strategic KPIs are particularly suitable for monitoring and keeping an eye on long-term targets,21 Neumann, K. (2020). Key Performance Indicator – Der Schlüssel zu mehr Marketing Performance. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://marketingexcellencegroup.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/KPI-Der-Schluessel-zu-mehr-Marketing-Performance.pdf. which is of high importance for sustainability. Overall, it can be stated that the measurement and evaluation of possible measures in the area of sustainability management is indispensable. Success can only be assessed by evaluating relevant measures. For many companies, including the Otto Group, this evaluation is part of a sustainably oriented corporate strategy. Therefore, both the sustainability of individual products, including their components, and the sustainable orientation of the entire value-added process are relevant for the measurement and evaluation of sustainability. The “Eco Index beta.org” and “Sustainable Apparel Coalition” concepts, among others, offer an evaluative approach for the Otto Group. In its assessment, the “Eco Index” distinguishes between individual stages of the value creation process and the entire value chain. The value chain is divided into six steps—from material extraction to distribution and recycling of the materials used. The “Sustainable Apparel Coalition” also assesses data along the entire value chain. Consequently, the development and implementation of possible indices are still in the process of creation and testing. However, the need for evaluation and measurement has been recognized because “you can’t manage what you don’t measure.”22 Brock, C. & Streubig, A. (2014). Nachhaltigkeitsmanagement am Beispiel der Otto Group – Herausforderungen, Strategie und Umsetzung. In H. Meffert, P. Kenning, & M. Kirchgeorg (Ed.), Sustainable Marketing Management: Grundlagen und Cases. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

3 Implementation

When implementing sustainability marketing, the company has to be aware of its vision and mission with regard to the three dimensions described above (ecological, economic and social). Orientation is usually based on the sustainability standards of the international community, which define overarching goals directed at companies.23 United Nations (2021). The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2021. Retrieved on 10/08/2021: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2021.

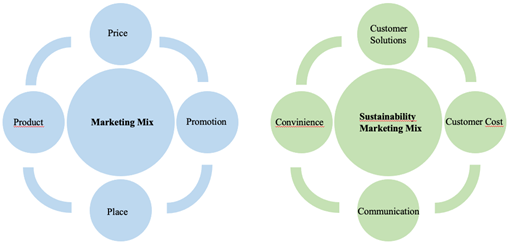

In marketing, the marketing mix is the best-known business tool and serves the company to increase its market performance in terms of sales and competitiveness. The marketing mix consists of four dimensions: Product, Price, Place and Promotion (4 P´s). The product refers to all possible objects and services that can be acquired by the customer and satisfy their needs. The customer needs the price as an exchange value for the acquisition. Place, in turn, includes all possible distribution channels through which products can be offered and sold to customers. Finally, promotion includes various communication measures to inform all stakeholders about the advertised products, the brand or the company itself.4 Kenning, P. (2014). Sustainable Marketing – Definition und begriffliche Abgrenzung. In Balzer, N. (2020). Konsumverhalten. Was motiviert zum Kauf nachhaltiger Lebensmittel?. GRIN Verlag.

A best practice example, which M. Koene et al. describe with regard to sustainability marketing in the context of the marketing mix, is the development and introduction of “compressed deodorants” by Unilever. For the implementation of product innovation, it is important to test the acceptance of the new product in the market. For this purpose, all brand management processes were run through, including a situation analysis in four countries, in which factors such as customers’ environmental awareness and consumer tests were examined. Unilever’s goal was to achieve sustainable growth in the deodorant category, i.e., to expand its market leadership while reducing its environmental impact. The strategy involved the selected target groups, as well as relevant stakeholders, in the dialogue to strengthen the brand positioning.

Using the marketing mix as a tool, it was first necessary to develop a product innovation as part of the product policy, which Unilever successfully achieved with the new spray head in the compressed deodorants, which released the same amount of active ingredients but with less propellant gas. This also reduced the package size and aluminum needs for production, which brings advantages for transport because less storage space is required. The resource savings and more efficient logistics resulted in a 25% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.

For the consumer, therefore, there are no changes apart from the smaller package size. There are also no changes in the pricing policy, and a constant price–performance level can be observed. However, the additional ecological benefit, i.e., the smaller packaging, initially leads customers to assume that they are getting less performance for the same price, which is why product innovation requires an explanation and must be properly communicated to the outside world.24 Koene, M., Wagner, K., Buerke, A. & Kirchgeorg, M. (2014). Nachhaltigkeitsmarketing in der Konsumgüterindustrie am Beispiel der Unilever Deutschland GmbH. In H. Meffert, P. Kenning, & M. Kirchgeorg (Ed.), Sustainable Marketing Management: Grundlagen und Cases. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

In the context of the distribution policy, it can be stated first that predominantly women show interest in the deodorants and are responsible for its purchase in 70% of the households that used the product. Based on these findings, the strategy was developed to launch the compressed deodorants among women first. This was based on the assumption that it would be easier to launch the product among men if it was already available in the women’s segment. In addition, parallel distribution of both the new and the old packaging was planned to ensure gradual familiarization and thus avoid negative word-of-mouth effects, so that the share of the new products could be gradually increased more quickly. In the German market, the launch was rather challenging, as consumers tend to be critical and demand a more transparent information policy. For this reason, product innovation was first introduced in the UK to better test consumer acceptance.21 Koene, M., Wagner, K., Buerke, A. & Kirchgeorg, M. (2014). Nachhaltigkeitsmarketing in der Konsumgüterindustrie am Beispiel der Unilever Deutschland GmbH. In H. Meffert, P. Kenning, & M. Kirchgeorg (Ed.), Sustainable Marketing Management: Grundlagen und Cases. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

The design of the communication channels for the launch of compressed deodorants takes place at the point of sale. To obtain consumers’ attention to product innovation, placement on the shelf is crucial. Products that are higher up or at the eye level attract the most attention, which is why Unilever places new products right next to old ones. To ensure that the smaller packaging does not attract direct attention, Unilever utilized shelf trays, which also serve as a communication medium to explain the core message and draw customers’ attention to the additional ecological benefits. Information brochures on the shelf, as well as separately placed displays and communication pillars, also attract attention. Store employees are prepared for the new product and serve as brand ambassadors. The first priority is to communicate the core message. To do this, Unilever employed cross-media campaigns using TV advertising, social media channels, and its own website. It was important to address the environmental benefits and use them across markets and thus meet customer needs by, for example, highlighting the benefits of the product, such as gentle care or better efficacy. The consumer tests led to the assumption that women in particular see an advantage in the product concept, for example, in the fact that the smaller packaging also makes it practical to use on the go. This is why communication is also increasingly taking place in this segment.21 Koene, M., Wagner, K., Buerke, A. & Kirchgeorg, M. (2014). Nachhaltigkeitsmarketing in der Konsumgüterindustrie am Beispiel der Unilever Deutschland GmbH. In H. Meffert, P. Kenning, & M. Kirchgeorg (Ed.), Sustainable Marketing Management: Grundlagen und Cases. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

Since the introduction of product innovation is geared toward customer needs with the highest priority, the changeover results in greater complexity for retail partners. For this reason, retailers were involved in advance planning, which has many advantages for retail companies. On one hand, the smaller packaging of the products makes it possible to increase shelf profitability, as there is 20% more space for deodorant cans, which means that more sales can be generated in a smaller area. On the other hand, the out-of-stock risk decreases as there is a higher availability of the products. The less frequent refilling of the shelves by store personnel and special shelf trays represents a lower workload and a further advantage. The retailers are also given the opportunity to distinguish themselves with this initiative more sustainability area and thereby strengthen the image.21 Koene, M., Wagner, K., Buerke, A. & Kirchgeorg, M. (2014). Nachhaltigkeitsmarketing in der Konsumgüterindustrie am Beispiel der Unilever Deutschland GmbH. In H. Meffert, P. Kenning, & M. Kirchgeorg (Ed.), Sustainable Marketing Management: Grundlagen und Cases. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

The application of the marketing mix, as in the best practice example, can therefore be seen as a suitable instrument for sustainability marketing. This model shows the traditional form of marketing but reflects more the view of the seller and not the buyer, which could result in the misinterpretation of needs. In fact, the goal of sustainability marketing is to motivate customers to accept and purchase sustainable products and services and to avoid or even reject non-sustainable products. For this reason, these sustainability aspects have been taken into account and the 4 P´s have been transformed into the 4 C´s (see Figure 3) in further developing this method. The sustainability marketing mix is intended to illustrate the transformation of sustainability and marketing.1 Belz, F. M. & Peattie, K. (2012). Sustainability Marketing: A global perspective. 2nd Ed.Chichester: Wiley.

The sustainability marketing mix focuses on customer relationships and sustainable development. The 4 C´s describe customer solutions, customer costs, communication and convenience. Customer solutions are problem solving rather than product selling and focus on customer needs, taking into account social and environmental boundaries. Customer costs does not mean the price of a product, but rather the psychological, social and environmental costs incurred in the procurement, use and disposal of a product. With regard to communication, the classic one-sided advertising process is pushed into the background and the interactive dialogue with the community is strengthened. This creates credibility and builds trust with the customer, which influences their way of thinking. Finally, convenience means that customers are offered specific products and services that meet their needs quickly and conveniently.1 Belz, F. M. & Peattie, K. (2012). Sustainability Marketing: A global perspective. 2nd Ed.Chichester: Wiley.

This model is fundamentally based on the traditional model, and many aspects of the implementation can be found in the best practice example, as these were indirectly included. The focus in the sustainable marketing mix is comparatively less on the product and more on the image of the company and its brand, which should be as sustainable as possible. In this context, more emphasis is placed on communication and interaction. In this respect, the focus of this chapter is on the communication measures that companies should take into account when implementing sustainable marketing.

Simultaneous with general communication measures, sustainability communication also refers to the consumer’s desire for need satisfaction.25 Schrader, U. (2005). Von der Öko-Werbung zur Nachhaltigkeits-Kommunikation in Belz, F. & Bilharz, M. (2005). Nachhaltigkeits-Marketing in Theorie und Praxis (pp. 61-74). Wiesbaden: Deutscher Universitäts-Verlag. Consumption patterns have changed in many areas, and sustainability aspects have become increasingly important. Accordingly, price is no longer the only decisive purchase criterion; the manner the product was manufactured and the ecological contribution it or the sales outlet makes are also taken into account.26 Charter, M., Peattie, K., Ottman, J. & Polonsky, MJ. (2002). Marketing and sustainability. Published by Centre for Business Relationships, Accountability, Sustainability and Society (BRASS), in association with The Centre for sustainable Design.

With the use of communication measures, on the one hand, a company can express its commitment to sustainability, but on the other hand, some areas of tension also arise. Content requirements, whereby completeness and materiality, complexity and comprehensibility, and comparability and uniqueness must be weighed against each other. Also, the problem of credibility must also be considered, because this can only be established “outside” corporate communication. In this context, a fine line to greenwashing is regularly present. To minimize this risk, certain guidelines have been designed. Companies should adapt the instruments used for their communication to individual information needs and demands. For this purpose, a differentiation is made between the four fields of action: employees, market, environment and community.23 Charter, M., Peattie, K., Ottman, J. & Polonsky, MJ. (2002). Marketing and sustainability. Published by Centre for Business Relationships, Accountability, Sustainability and Society (BRASS), in association with The Centre for sustainable Design.

The integration of employees and the constant motivation for personal and shared responsibility increases the credibility of a company externally and are also suitable for inclusion in a corporate mission statement for anchoring sustainability orientations. Wilkhahn describes the following as a key success factor for the company: “We involve our employees, dealers, customers and opinion leaders in the implementation of the corporate mission statement. We will inform them about developments in sustainability management and involve them appropriately in further development.”23 Charter, M., Peattie, K., Ottman, J. & Polonsky, MJ. (2002). Marketing and sustainability. Published by Centre for Business Relationships, Accountability, Sustainability and Society (BRASS), in association with The Centre for sustainable Design.

Communication in the market can be characterized by the balance and the right choice of spatial and personal proximity and distance. For this, it is a prerequisite that the sustainability strategy is closely linked to the corporate strategy and thus that there is a natural link between the sustainability positioning and brand identity.27 Andree, I. & Dr. Hahn, C. (2014). Nachhaltigkeit in der Kommunikationspolitik: “Deutsche Telekom” in Meffert, H., Kenning, P. & Kirchgeorg, M. (2014). Sustainable Marketing Management – Grundlagen und Cases (pp. 227-250). Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

In the field of environmental action, a company gains trust and image through transparency measures and disclosure of compensation. In principle, it is not sufficient to inform consumers about a sustainable alternative or to position themselves individually with this alone. Rather, it is necessary to pass on knowledge about the relevant topic area. For example, the manufacturer of a harmless, biodegradable cleaning agent should inform the consumer that conventional products are harmful to the environment.28 Claessens, M. (2019). Sustainable Marketing Strategies – How to go about a green marketing strategy? Retrieved on 04/08/21: https://marketing-insider.eu/sustainable-marketing-strategies/.

The field of community is closely related to the employee field of action with regard to the communication of CSR and sustainability, as active involvement is also a crucial aspect in this regard.29 Keck, W. (2018). Wer? Was? Wann? Wo? Warum? Wozu? In Heinrich, P. (2018) CSR und Kommunikation – Unternehmerische Verantwortung überzeugend vermitteln (pp. 301-309). Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler. A good example is the company Baufritz. This medium-sized company was able to successfully position itself on the market as an eco-company with its sustainable and certified building material and thus generate competitive advantages. Baufritz has also been able to distinguish itself through its outward social commitment, presence on opinion platforms, and strong dialogue-oriented and innovative communication instruments, whereby it is mainly a matter of getting into contact with the community.30 Baumgarth, C. & Binckebanck, L. (2014). Best Practices der CSR-Markenführung und –Kommunikation in Meffert, H., Kenning, P. & Kirchgeorg, M. (2014) Sustainable Marketing Management – Grundlagen und Cases (pp. 175-204). Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

In the following section, the focus is placed on the detailed presentation of the instruments of communication, as these represent an essential component of the implementation of sustainability marketing in a company. Basically, it is not decisive how many different instruments a company uses specifically for the communication of sustainability aspects; rather, it is important to select the right combination according to communication goals.

One instrument of communication is professional media relations. To ensure a successful entry into this topic area as a company, many begin by strategically integrating their CSR activities into their media work. Even today, a corresponding corporate image is mainly created through mass media, such as the press and social media. Because of this, mass media is a very effective field of action for CSR communication, and it is also the best way to communicate sustainability. It should not be forgotten that the employees of a company are also consumers of mass media. Media and press relations involve building trust-based relationships with journalists and bloggers. This automatically transfers credibility in the information transmitted.31 Heinrich, P. (2018). CSR und Kommunikation – Unternehmerische Verantwortung überzeugend vermitteln. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

Furthermore, topic management is an important area of media work. In principle, CSR communication must focus thematically on the social commitment of a company. For this purpose, it is crucial to develop one’s own topics for the public. This requires regular and systematic observation and analysis of a broad and diverse media base. Crisis communication is a particularly important area, as the wrong reaction or even the lack of reaction can have resentful consequences.28 Heinrich, P. (2018). CSR und Kommunikation – Unternehmerische Verantwortung überzeugend vermitteln. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

Another communication instrument is reporting or publication. In sustainability marketing, the instrument is concretized as a targeted communication of the company’s value. A decisive component here is the responsible use of resources, as well as social, cultural and charitable commitment. A pioneer of sustainability reporting is the company Henkel, which has been reporting successfully for 30 years. The company focuses on continuous development in this area and includes many topics defined by stakeholders for the future success of the company.32 Henkel (2020). Nachhaltigkeitsbericht 2020. Retrieved on 30/07/2021: https://www.henkel.de/nachhaltigkeit/nachhaltigkeitsbericht

Online communication is to be considered one of the main communication tools in today’s world. This is because the transmission of sustainability information reaches a broad audience within a very short time and imposes the possibility of entering into a dialogue with people from all over the world. In addition to the positive aspects, however, online communication is also accompanied by challenges. For example, it gives stakeholders a platform on which they can publicly discuss claims against the company at any time and build up pressure. Another online contact point is the company’s own website. The company’s own online press portal should be easily accessible for both external and internal recipients in order to ensure the quickest and easiest access to materials and information.28 Heinrich, P. (2018). CSR und Kommunikation – Unternehmerische Verantwortung überzeugend vermitteln. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

For the company H&M, social media channels are an efficient way to communicate about sustainable fashion or brand-building activities. These can be events or films, among other things, where information and inspiration can be conveyed. The “storytelling” approach has proven to be a very effective social media strategy. This clarifies the company’s vision within a narrative framework and conveys content in an interesting way for an increasingly short attention span. This is accompanied by an easily understandable and comprehensible brand. A vivid and well-known example of this is the Edeka campaign, which reached consumers and their sustainability awareness in an emotional way.28 Heinrich, P. (2018). CSR und Kommunikation – Unternehmerische Verantwortung überzeugend vermitteln. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler. The last instrument is, again, specific personal communication or events. Here, direct conversation guarantees the exchange of information and the possibility of responding to questions, criticism and incentives and of responding with personal communication, because the essence of the company can thus be experienced actively. Furthermore, it is also an efficient means of communicating transparency, credibility and legitimacy.28 Heinrich, P. (2018). CSR und Kommunikation – Unternehmerische Verantwortung überzeugend vermitteln. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler. The implementation of sustainability marketing can be designed differently depending on the company. Inevitably, however, it is a long-term task for the future that must also be understood with a certain continuity and permanence. Accordingly, the use of basic instruments is indispensable.

4 Drivers and barriers

There are firm-internal and external factors that drive and hinder sustainability marketing. To examine the effect of these factors on sustainability marketing, the different aspects of the marketing mix must be considered. As consumers play the most important role and the marketing mix focuses on them,33 Patel, N. (2021): Die 4 Ps des Marketings: Eine Schritt-für-Schritt-Anleitung (mit Beispielen). Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://neilpatel.com/de/blog/die-4-ps-des-marketings/. 34 Mödinger, W. (2016). Kirchenmarketing. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Oldenbourg. 35 Išoraitė, M. (2020). Marketing Mix Features. In: Ecoforum Journal, Vol. 23, No. 1. any factors influencing the consumers’ behavior must also be considered as stimulators or hindrances to sustainability marketing. Therefore, the following chapter will deal with the drivers of and barriers to sustainability with special regard to marketing mix and consumer behavior.

4.1 External drivers and barriers

PESTEL analysis is a tool for analyzing different external factors that influence a company. Each category of external factors is represented by a letter. “P” stands for political aspects, “E” for economic, “S” for social and cultural, “T” for technological, “E” for environmental and “L” for legal ones.36 Yüksel, I. (2012). Developing a multi-criteria decision making model for PESTEL analysis. International Journal of Business and Management, 7(24), 52. On account of the fact that this tool is perfectly suited for examining firm-external factors, this work will use the basic structure and categories of the PESTEL analysis with special regard to sustainability to analyze what factors of the different categories might drive or hinder sustainability marketing.

As it can be hard to distinguish between political and legal aspects due to their interconnection, they will be combined in the following subsection. Political regulations and legislation concerning environmental protection serve as drivers for sustainability marketing.8 Lim, W. M. (2016). A blueprint for sustainability marketing: Defining its conceptual boundaries for progress. Marketing Theory, 16(2), 232-249. Companies have to react to these regulations by taking measures to include sustainability aspects in their business activities in order to comply with the new legislation. Successfully including environmentally friendly practices and complying with environmental regulations enable firms to include these into their business models and generate profit out of the newly created social and ecological value.37 García-Muiña, F. E.; Medina-Salgado, M. S.; Ferrari, A. M. & Cucchi, M. (2020). Sustainability Transistion in Industry 4.0 and Smart Manufacturing with the Triple Layered Business Model Canvas. Sustainability, 12(6), pp. 1-19. Directly influencing products and services, which belong to the marketing mix, companies can then benefit from newly generated social or ecological values by communicating them to customers through sustainability marketing.1 Belz, F. M. & Peattie, K. (2012). Sustainability Marketing: A global perspective. 2nd Ed.Chichester: Wiley. 2 Belz, F. M. & Peattie, K. (2010). Sustainability Marketing: An Innovative Conception of Marketing. Marketing Review St Gallen, 27, 8-15. IKEA and Nokia are two instances mentioned earlier that illustrate how sustainability can be sold well due to sustainability marketing.8 Lim, W. M. (2016). A blueprint for sustainability marketing: Defining its conceptual boundaries for progress. Marketing Theory, 16(2), 232-249. Additionally, there are laws that directly influence aspects of the marketing mix and therefore influence sustainability marketing. An example of legislation driving sustainability marketing more directly is the New Companies Act of 2014 from India. The Act includes mandatory CSR activities for companies.38 Mishra, S., & Banerjee, G. (2019). A Study on the Impact of Mandatory Provisions on CSR Strategies of Indian Companies. In I. Altinbasak-Farina, & S. Burnaz (Ed.), Ethics, Social Responsibility and Sustainability in Marketing (pp. 145-154). Singapore, Singapore: Springer Nature. Even though CSR and sustainability marketing are to be differentiated, the strong interconnection makes this law a good example for sustainability marketing impelling political and legal factors. A further example is the Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive of the EU, which aimed to reduce packaging waste and promote recycled packaging,39 Europäische Kommission (n.d.). Packaging waste. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/topics/waste-and-recycling/packaging-waste_de. consequently directly incentivizing sustainable packaging, which belongs to the marketing mix. Another political inducement for sustainability in companies and sustainability marketing is subsidies. Different kinds of subsidies pose incentives for companies to integrate sustainability aspects into their business and therefore impel sustainability throughout the whole marketing mix40 Eurostat (2015). Environmental subsidies and similar transfers: Guidelines. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3859598/6923655/KS-GQ-15-005-EN-N.pdf/e3be619b-bb19-4486-ab23-132a83f6ff24. Furthermore, politics can play a role in educating the public concerning sustainability-related issues and challenges, thus influencing consumption behavior.41 Die Bundesregierung (2021). Bericht über Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung: Nachhaltigkeit muss Teil der Bildung sein. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/suche/bericht-bildung-nachhaltige-entwicklung-1892154. In contrast, a conservative government that is opposed to environmental protection can hinder sustainability marketing in companies by lifting regulations, influencing the public or releasing environmental harmful subsidies. A good example is the Trump Administration, which rolled back 100 environmental rules,42 Buchholz, K. (2020). Trump Administration Reversed 100 Environmental Rules. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://www.statista.com/chart/18268/environmental-regulations-trump-administration/. which encouraged companies to disintegrate sustainability measures, i.e., “the administration is eliminating requirements for oil and gas companies to report methane emissions and calculate the ‘social cost of carbon,’ an Obama-era rule meant to estimate the long-term benefits of reducing carbon dioxide emissions.”39 Buchholz, K. (2020). Trump Administration Reversed 100 Environmental Rules. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://www.statista.com/chart/18268/environmental-regulations-trump-administration/.

An economic factor influencing sustainability marketing can be the population’s purchasing power and willingness to pay, as these factors are interconnected with the companies’ price policy for sustainable products. On the one hand, higher prices for sustainable products generally prevent people with low purchasing power from buying them.43 Balzer, N. (2020). Konsumverhalten. Was motiviert zum Kauf nachhaltiger Lebensmittel?. GRIN Verlag. On the other hand, people have a higher willingness to pay for sustainable products in wealthier industrial countries, such as Germany.44 Breitkopf, A. (2020). Um wieviel Prozent dürfte ein nachhaltig und umweltschonend hergestelltes Produkt maximal teurer sein als ein konventionell erzeugtes Produkt, damit Sie es für einen Kauf in Erwägung ziehen würden?. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/1154639/umfrage/umfrage-zur-preisbereitschaft-bei-nachhaltigen-produkten/. In conclusion, higher purchasing power can be a driver of sustainability marketing, while low purchasing power serves as a barrier because marketing is mainly aimed at consumers and includes catching their willingness to pay. Thus, any economic factors that impact purchasing power and willingness to pay can be considered drivers or barriers, respectively. Examples of economic factors are financial crises and poverty, as well as inflation, deflation and unemployment rates. Corporate lobbying against climate change and the use of conservative think tanks or front groups that influence public opinion on climate change, strategies carried out by big oil companies such as Exxon, can be further barriers,45 Beder, S. (2011): Lobbying, Greenwash and Deliberate Confusion: How Vested Interests Undermine Climate Change Regulation. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275276392_Lobbying_Greenwash_and_Deliberate_Confusion_How_Vested_Interests_Undermine_Climate_Change_Regulation. as they influence the political and social sphere. Nevertheless, companies can also encourage sustainable consumption, which will be explained in greater detail later. Furthermore, high prices for resources needed for sustainable production, such as renewable energies, act as another hurdle to sustainability, as they in return influence the price of the products.46 Boetius, A., Brudermüller, M., Lücke, W., Nanz, P., Oswald, J., & Römer, J. (2020). Nachhaltigkeit im Innovationssystem. Impulspapier des Hightech-Forums. Hightech-Forum. A strong competition in a market can also act as an incitement for sustainability marketing, as a “growing number of companies are looking to emphasize their commitment to sustainability in an attempt to help to differentiate themselves from their competitors and to enhance their corporate brand and reputation”9 Jones, P., Clarke-Hill, C., Comfort, D. & Hillier, D. (2007). Marketing and sustainability. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 26(2), 123-130. in order to obtain a competitive advantage. Environmental labels can also promote sustainable consumption.47 Thogersen, J. (2002). Promoting green consumer behavior with eco-labels. New Tools for Environmental Protection, 83-104. Simultaneously, they create more opportunities for sustainability marketing and are therefore further driving forces. An example of such a label is the German “Blauer Engel,” a label that certifies different products or services as environmentally friendly through continuous monitoring and assessment throughout the whole lifecycle.48 Blauer Engel (n.d.). Was steckt dahinter?. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://www.blauer-engel.de/de/blauer-engel/was-steckt-dahinter.

As consumers play a key role in the marketing mix and sustainability marketing,49 Altinbasak-Farina, I., & Guleryuz-Turkel, G. (2019). Profiling Green Consumersin an Emerging Country Context. In I. Altinbasak-Farina, & S. Burnaz (Ed.), Ethics, Social Responsibility and Sustainability in Marketing (pp. 193-214). Singapore, Singapore: Springer Nature. social and cultural factors that shape the consumers’ values, needs and behavior in general have to be considered as drivers and barriers. The demand for sustainable clothing could be treated as an indicator of the value of sustainability in a society or culture. While there is an increasingly high demand for sustainable clothing in Western countries, such as Germany and Scandinavian countries, there is nearly no demand for these in India.50 Lindner, E. (n.d.). Nachhaltige Mode: Diese Marken und Produkte sind in Deutschland am beliebtesten. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://www.lyst.de/artikel/diese-nachhaltigen-marken-und-produkte-sind-in-deutschland-am-beliebtesten/. Thus, sustainability marketing would not be as effective in India as it would be in Germany. This shows that different cultures and values can either impede or impel sustainability marketing in various countries. This is also consistent with the facts that Indian companies show no efforts to invest in CSR activities and that sustainability is neither a priority from the political perspective nor from the society’s perspective,35 Mishra, S., & Banerjee, G. (2019). A Study on the Impact of Mandatory Provisions on CSR Strategies of Indian Companies. In I. Altinbasak-Farina, & S. Burnaz (Ed.), Ethics, Social Responsibility and Sustainability in Marketing (pp. 145-154). Singapore, Singapore: Springer Nature. 51 Keppner (2014) while in a lot of other countries there is an increased demand for sustainable products.52 Haller, K., Lee, J., & Cheung, J. (2020). Meet the 2020 consumers driving change. Why brands must deliver on omnipresence, agility, and sustainability. IBM Institute for Business Value. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://www.ibm.com/downloads/cas/EXK4XKX8. A study conducted by IBM found that 40% of approximately 18,000 consumers surveyed were seeking products that align with their personal values.49 Haller, K., Lee, J., & Cheung, J. (2020). Meet the 2020 consumers driving change. Why brands must deliver on omnipresence, agility, and sustainability. IBM Institute for Business Value. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://www.ibm.com/downloads/cas/EXK4XKX8. This emphasizes the importance of social factors, such as values or beliefs, and underlines their function as drivers of sustainability marketing. So called “Green Consumers,” “who try to translate their sustainable values into purchasing criteria,”9 Jones, P., Clarke-Hill, C., Comfort, D. & Hillier, D. (2007). Marketing and sustainability. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 26(2), 123-130. can help marketing by showcasing how to encourage sustainable purchasing and how to utilize ecological and social values in order to foster consumption.9 Jones, P., Clarke-Hill, C., Comfort, D. & Hillier, D. (2007). Marketing and sustainability. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 26(2), 123-130. In contrast, consumers who are not willing to pay higher prices, have no awareness of sustainability-related issues, have a lack of trust in the company or face any other obstacles like lack of choice, effort to change or convenience constitute a threat to sustainability marketing.9 Jones, P., Clarke-Hill, C., Comfort, D. & Hillier, D. (2007). Marketing and sustainability. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 26(2), 123-130.46 Altinbasak-Farina, I., & Guleryuz-Turkel, G. (2019). Profiling Green Consumersin an Emerging Country Context. In I. Altinbasak-Farina, & S. Burnaz (Ed.), Ethics, Social Responsibility and Sustainability in Marketing (pp. 193-214). Singapore, Singapore: Springer Nature. Other social factors inciting or obstructing sustainability and ultimately sustainability marketing are demographics and family composition. A study conducted in Turkey also revealed a strong correlation between age and sustainable behavior. Older generations tend to behave less sustainably, while younger generations do the opposite.46 Altinbasak-Farina, I., & Guleryuz-Turkel, G. (2019). Profiling Green Consumersin an Emerging Country Context. In I. Altinbasak-Farina, & S. Burnaz (Ed.), Ethics, Social Responsibility and Sustainability in Marketing (pp. 193-214). Singapore, Singapore: Springer Nature. Thus, it can be presumed that the demographic structure of a country can also act as an impetus or hurdle. The same study showed that married people and families with children tend to engage in more sustainable behavior. The study also revealed that higher income also correlates with more sustainable behavior,46 Altinbasak-Farina, I., & Guleryuz-Turkel, G. (2019). Profiling Green Consumersin an Emerging Country Context. In I. Altinbasak-Farina, & S. Burnaz (Ed.), Ethics, Social Responsibility and Sustainability in Marketing (pp. 193-214). Singapore, Singapore: Springer Nature. which is consistent with the statements concerning the population’s willingness to pay and purchasing power influencing sustainability. There are also psychological hindrances, such as different denial mechanisms, that obstruct sustainable consumption and, therefore, sustainability marketing. People or social groups denying the existence of the problem of climate change, its risks, and their responsibility, as well as simply not acting out of the feeling of helplessness,53 Dursum, I. (2019). Psychological Barriers to Environmentally Responsible Consumption. In I. Altinbasak-Farina, & S. Burnaz (Ed.), Ethics, Social Responsibility and Sustainability in Marketing (pp. 103-128). Singapore, Singapore: Springer Nature. are such barriers for sustainability marketing.

External technological factors can also impact sustainability marketing. The internet has led to stronger global connectivity and enables easier access as well as exposure to information regarding sustainability-related issues. As a result, awareness is being raised among different stakeholders. In addition, technological connection eases a joint problem-solving process regarding unsustainable consumption and practices.8 Lim, W. M. (2016). A blueprint for sustainability marketing: Defining its conceptual boundaries for progress. Marketing Theory, 16(2), 232-249. Moreover, technological aspects like mobile payment, social media and online opinions influence consumers’ behavior and open up new markets and communication channels.54 Taylor, K. (n.d.). How Technology Influences Consumer Behavior?. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://www.hitechnectar.com/blogs/technology-consumer-behavior/#AugmentedReality. In fact, an increasing number of companies are utilizing e-word of mouth for marketing purposes, which can also be applied for sustainability marketing.55 Gleich, U. (2014). Werbewirkung–Gestaltungseffekte und Rezipientenreaktionen. Media Perspektiven, 7-8, 420-425. Taking all these aspects into account, it becomes evident that technological factors such as the rate of digitalization, internet connection and its necessary infrastructure are drivers of sustainability marketing, while their absence represents a barrier to it. The technological infrastructure necessary for sustainable or more efficient operational and business processes, as well as innovations, can also act as an enabler for sustainability marketing, as these ease the creation of more sustainable products. Thus, vice versa, the absence of such infrastructure, such as a lack of renewable energy sources constitute an obstacle.43 Boetius, A., Brudermüller, M., Lücke, W., Nanz, P., Oswald, J., & Römer, J. (2020). Nachhaltigkeit im Innovationssystem. Impulspapier des Hightech-Forums. Hightech-Forum.

56 Korsofsky, A. (2021). What Are the Six Factors of Sustainability, and How Can We Adhere to Them?. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://www.greenmatters.com/p/six-factors-of-sustainability.

Ecological or environmental factors pose additional stimulators or hindrances to sustainability and, as a result, sustainability marketing. Natural disasters such as hurricanes and extreme weather influence people’s attitude towards sustainability. A study conducted in the USA revealed that people changed their minds on the matter of climate change after having personally experienced a hurricane. Their willingness to pay to mitigate climate change has increased after experiencing extreme weather.57 Bergquist, M., Nilsson, A., & Schultz, P. (2019). Experiencing a severe weather event increases concern about climate change. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 220. This could potentially also be applied to other natural disasters similar to extreme weather or other forms of extreme weather, such as floods, air pollution and water shortages. Even though further research is needed, an assumption that could be derived from the study is that environmental factors that are caused by climate change and that cause damage to people are an impetus for sustainable behavior, which in return favors sustainability marketing. The lack of local resources mentioned earlier also represents an ecological hurdle and encourages global sourcing and, as a result, long-range transportation, potentially inhibiting sustainability in the distribution,58 Christopher, M., Jia, F., Khan, O., Mena, C., & Sandberg, E. (2007). Global sourcing and logistics. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308402707_Global_Sourcing_and_Logistics59 Kaufmann, L., & Hedderich, F. (2005). A novel framework for international sourcing applied which is also part of the marketing mix.

Overall, there are a lot of external factors that either stimulate or hinder sustainability marketing directly or indirectly. The abovementioned factors are just examples and there are certainly more firm-external drivers or barriers, which have not explicitly been mentioned here. Furthermore, the presented factors and their intensity may also differ between different countries and industries.

4.2 Internal drivers and barriers

Besides the firm-external drivers of and barriers to sustainability marketing, there are also firm-internal factors that influence it. Again, there is a strong interconnection between sustainability throughout the whole company and sustainability marketing, as this function is dependent on sustainability measures in other functions, and the marketing mix also includes different areas of companies.

First, a business model and a product or service that do not allow for the integration of sustainability into the marketing mix constitute the first major obstacle. Big oil companies, such as Shell, whose core businesses necessitate the use of fossil fuels, could have hardships marketing their products as sustainable without changing their core competencies, as the sole compensation for their business activities is not enough to make up for the environmental damage they cause.60 Monbiot, G. (2019). Shell is not a green saviour. It’s a planetary death machine. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/jun/26/shell-not-green-saviour-death-machine-greenwash-oil-gas. Additionally, having a customer target group that does not prioritize sustainability over other factors, such as price, makes sustainability marketing even harder. The next hurdle is spreading sustainable thinking throughout the whole company, as it is important for every single employee to be engaged. Having all the companies on the same page makes it easier to market sustainability and establish a sustainable brand image, which is necessary for successful sustainability marketing. Strict performance measures and too much pressure to hit specific goals can overshadow the sustainability aspect and lead to employees ignoring it.9 Jones, P., Clarke-Hill, C., Comfort, D. & Hillier, D. (2007). Marketing and sustainability. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 26(2), 123-130. Furthermore, companies not being aware of the fact that their processes already reduce environmental impact along with the inability to judge their sustainability level and include sustainability in the value creation of products and services, which are a part of the marketing mix, pose further firm-internal impediments to sustainability marketing.34 García-Muiña, F. E.; Medina-Salgado, M. S.; Ferrari, A. M. & Cucchi, M. (2020). Sustainability Transistion in Industry 4.0 and Smart Manufacturing with the Triple Layered Business Model Canvas. Sustainability, 12(6), pp. 1-19. Therefore, the absence of KPIs and methods to analyze or measure sustainability in the different functions concerning the marketing mix, as well as the previously mentioned KPIs for sustainability marketing, hinder the function itself. Organizational inertia, which leads to companies acting slowly or ignoring changes in their environment, can also be problematic, as it increases the risk of not reacting to sustainability-related issues61 Stal, H. I. (2015). Inertia and change related to sustainability–An institutional approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 99, 354-365. and ultimately impedes sustainability marketing. Thus, a business culture that favors organizational inertia can also be seen as a barrier. Moreover, wrong approaches to sustainability marketing, such as messages focused on the product instead of consumers’ needs that lead to the potential risk of being deemed as greenwashing,62 Villarino, J., & Font, X. (2015). Sustainability marketing myopia: The lack of persuasiveness in sustainability communication. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 21(4), 326-335. can obstruct the function itself. In addition, an unfavorable financial situation can also impede sustainability marketing, as companies tend to cut marketing expenses during financial hardships.63 Kumar, N., & Pauwels, K. (2021). Weiter Geld ausgeben – aber anders. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://www.manager-magazin.de/harvard/marketing/marketing-warum-das-budget-in-der-krise-steigen-sollte-a-00000000-0002-0001-0000-000174319580. Another aspect to consider is that marketing teams are often not involved in sustainable business strategies and are not driving forces of sustainable services and products within companies.9 Jones, P., Clarke-Hill, C., Comfort, D. & Hillier, D. (2007). Marketing and sustainability. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 26(2), 123-130. Furthermore, there can be a lot of different teams and departments that deal with sustainability and communication with the public, such as PR teams, CSR teams and different marketing functions, whose precise coordination can be a further challenge that has the potential of hampering sustainability marketing.8 Lim, W. M. (2016). A blueprint for sustainability marketing: Defining its conceptual boundaries for progress. Marketing Theory, 16(2), 232-249. Lastly, excessively high prices and strict price policies regarding sustainable products can also appear as a firm-internal obstruction, since one of the main reasons consumers avoid sustainable products is high prices, as mentioned in the previous section.

Some firm-internal impetuses for sustainability marketing can be derived from the barriers mentioned above. Products, services or business models that easily allow for the integration of sustainability-oriented aspects, in contrast to the sale of fossil fuels, can impel sustainability marketing. A corporate structure and business culture that engage all employees on the matter of sustainability and prevent organizational inertia can further stimulate sustainability marketing. An agile business culture, for example, helps promote sustainability throughout the whole company by engaging every single employee and fostering open-mindedness as well as innovation. Not only does it prevent inertia, it also promotes the acceptance of different aspects that are important to sustainability marketing, such as customer-centered thinking and continuous feedback.64 Mörzinger, K. (2021). Wie kann Agilität die nachhaltige Transformation unterstützen?. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://www.eccos22.com/2021/04/13/wie-kann-agilitaet-die-nachhaltige-transformation-unterstuetzen/. Additionally, tools for developing or innovating sustainable business models, such as the triple-layered business model canvas, can help to assess social and ecological impacts and values created by the company. As a result, it becomes easier to implement sustainability-oriented countermeasures and market them.34 García-Muiña, F. E.; Medina-Salgado, M. S.; Ferrari, A. M. & Cucchi, M. (2020). Sus-tainability Transistion in Industry 4.0 and Smart Manufacturing with the Triple Layered Business Model Canvas. Sustainability, 12(6), pp. 1-19. Furthermore, firm-internal incentives to integrate sustainability into business can also be seen as drivers. Such incentives also include aspects of the marketing mix, such as cost-savings due to more efficient production enabling lower product prices, the opportunity to expand to new markets and customer groups, risk reduction, and more appeal to employees and other financial benefits.8 Lim, W. M. (2016). A blueprint for sustainability marketing: Defining its conceptual boundaries for progress. Marketing Theory, 16(2), 232-249. Marketing teams or departments can induce sustainability marketing themselves by influencing the consumer’s and organization’s behaviors. “Therefore, marketers can often focus on understanding and changing organizational behavior, through internal marketing, or consumer behavior, through marketing campaigns and marketing mix strategies.”8 Lim, W. M. (2016). A blueprint for sustainability marketing: Defining its conceptual boundaries for progress. Marketing Theory, 16(2), 232-249.

5 Best practice examples

The following section will provide best practice examples of companies overcoming some of the previously mentioned firm-internal and external barriers to sustainability marketing. In order to overcome the hurdle of unsustainable consumption and customer behavior, Unilever created a strategy to change its customers’ behavior. By understanding the habits and motivations of their consumers and combining them with different aspects of behavioral change, they successfully managed to launch sustainability marketing campaigns by influencing the consumption behavior of their customers. One aspect of the campaign was aimed at the reduction of water usage and the use of lower washing temperatures. After marketing a lower washing temperature by explaining the benefits, the average washing temperature in the EU decreased within three years.65 Bocken, N. (2017). Business-led sustainable consumption initiatives: Impacts and lessons learned. Journal of Management Development, 36(1), 81-96. 66 Drummond, J. (2021). Customer Behavior Change: The Holy Grail of Conscious Brands. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://sustainablebrands.com/read/behavior-change/customer-behavior-change-the-holy-grail-of-conscious-brands. Another example of fostering sustainable behaviors and consumer consumption is Marks and Spencer’s “Shwopping” initiative that encouraged customers to return unwanted clothing when buying new garments. Through this initiative, 7.8 million garments were returned.62 Bocken, N. (2017). Business-led sustainable consumption initiatives: Impacts and lessons learned. Journal of Management Development, 36(1), 81-96. Both examples showcase how companies can motivate their customers to behave more sustainably, which can be seen as a starting point for overcoming one of the major obstacles to sustainability marketing, namely, the unsustainable behavior of its consumers. Simultaneously, both companies generate social and ecological value and position their brands as sustainable. Thus, it can be derived that sustainability marketing itself can overcome its major barriers and turn them into drivers. At the same time, both companies also pose examples of overcoming the firm-internal impediment of wrong approaches to sustainability marketing and the threat of being deemed greenwashing. In particular, Unilever’s marketing campaigns seem to have been very successful, as their revenue grew significantly after the start of the campaigns.67 Macrotrends (2021). Unilever Revenue 2006-2021 | UL. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/UL/unilever/revenue. An example of a corporate culture that drives agility, innovation and sustainability is Patagonia. Patagonia approaches sustainability marketing through a unique strategy that challenges traditional consumerism. Instead of aggressively promoting products, Patagonia focuses on building a strong community that shares its values of sustainability and environmental protection. The company prioritizes community building over mass advertising, fostering a loyal customer base through direct interaction, events, and platforms like “Patagonia Action Works” for collective engagement. Patagonia emphasizes quality over quantity, producing durable, high-quality products designed to reduce consumption, contrasting with the fast fashion trend of short-lived items. Transparency and authenticity are central to Patagonia’s approach, as the company openly communicates its production processes, values, and environmental impact, building trust with customers. Despite these efforts, Patagonia faces the challenge of balancing growth with sustainability, particularly in the fast-paced fashion industry. Through these strategies, Patagonia demonstrates a commitment to sustainability that goes beyond marketing, embedding it into the core of its business practices. 68 Eberhardt, 2019. Patagonia-Marketingchef: „Wir machen keine Anti-Werbung“. https://www.absatzwirtschaft.de/patagonia-marketingchef-wir-machen-keine-anti-werbung-223954/

References

- 1Belz, F. M. & Peattie, K. (2012). Sustainability Marketing: A global perspective. 2nd Ed.Chichester: Wiley.

- 2Belz, F. M. & Peattie, K. (2010). Sustainability Marketing: An Innovative Conception of Marketing. Marketing Review St Gallen, 27, 8-15.

- 3Kumar, V., Rahman, Z. & Kazmi A. A. (2013). Sustainability Marketing Strategy: An Analysis of Recent Literature. Global Business Review, 14, 601–625.

- 4Kenning, P. (2014). Sustainable Marketing – Definition und begriffliche Abgrenzung. In Balzer, N. (2020). Konsumverhalten. Was motiviert zum Kauf nachhaltiger Lebensmittel?. GRIN Verlag.

- 5Kumar, V., Rahman, Z., Kazmi A. A. & Goyal, P. (2012). Evolution of sustainability as marketing strategy: Beginning of new era. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 37, 482 – 489.

- 6Griese, K. M. (2015). Nachhaltigkeitsmarketing – Eine fallstudienbasierte Einführung. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien

- 7Leimböck, E. (2017). Nachhaltigkeitsmarketing. In E. Leimböck, A. Iding & H. Meinen (Eds). Bauwirtschaft (pp. 587-590). Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

- 8Lim, W. M. (2016). A blueprint for sustainability marketing: Defining its conceptual boundaries for progress. Marketing Theory, 16(2), 232-249.

- 9Jones, P., Clarke-Hill, C., Comfort, D. & Hillier, D. (2007). Marketing and sustainability. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 26(2), 123-130.

- 10Islam, Q., & Ali Khan, S.M.F. (2024). Assessing Consumer Behavior in Sustainable Product Markets: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach with Partial Least Squares Analysis. Sustainability, 16, 3400. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16083400

- 11Spiller, A., Zühlsdorf, A., Schaltegger, S. & Petersen, H. (2007). Nachhaltigkeitsmarke-ting I: Grundlagen, Herausforderungen und Strategien.

- 12Steiger, S. C. (2017). KPIs – Kennzahlen: Wahl und Auswertung der richtigen Parameter. In H. Scholz (Ed.), Social goes Mobile – Kunden gezielt erreichen (2nd ed., pp. 211-227). Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

- 13Roberts, M. (2018). What is sustainability marketing? Retrieved on 29/07/2021: https://www.consciouscreatives.co.uk/planning/what-is-sustainability-marketing/.

- 14Meier, S. (2018). Kennzahlen im digitalen Marketing. Frankfurt am Main: Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels e.V.

- 15Elsässer, M. (2020). Moderne Marketing-KPIs mit echtem Mehrwert – wie funktio-niert’s?. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://www.pwc.de/de/im-fokus/customer-centric-transformation/marketing-advisory/moderne-marketing-kpis-mit-echtem-mehrwert-wie-funktionierts.html.

- 16Hristov, I. & Chirico, A. (2019). The Role of Sustainability Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) in Implementing Sustainable Strategies. Sustainability, 11(20), 1-19.

- 17Meier, S. (2018). Kennzahlen im digitalen Marketing. Frankfurt am Main: Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels e.V.

- 18Elsässer, M. (2020). Moderne Marketing-KPIs mit echtem Mehrwert – wie funktioniert’s?. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://www.pwc.de/de/im-fokus/customer-centric-transformation/marketing-advisory/moderne-marketing-kpis-mit-echtem-mehrwert-wie-funktionierts.html.

- 19Hristov, I. & Chirico, A. (2019). The Role of Sustainability Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) in Implementing Sustainable Strategies. Sustainability, 11(20), 1-19.

- 20United Nations (2021). The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2021. Retrieved on 10/08/2021: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2021.