Authors: Jana Beeck, Jennifer Kathrin Bialucha, Anna Gruber, Sophia Härter

Edited by: Luis Häcker, Katharina Landwehr, Benedikt Pröbstle, Miriam Schümmer, Lynn Weißer, Marthe Dreyer, Lea Wieser, Henrik Schneider, Maximilian von Wedel

Last updated: January 04, 2023

1 Definition and relevance

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defines climate change as “any change in climate over time, whether due to natural variability or as a result of human activity”.1IPCC. (2001). Climate change 2001: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: Contribution of Working Group II to the 3rd Assessment Report of the IPCC. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Climate change includes major changes in temperature, precipitation, or wind patterns, among others, that occur over several decades or longer.2EPA. (2017). Glossary of Climate Change Terms: Climate Change. https://19january2017snapshot.epa.gov/climatechange/glossary-climate-change-terms_.html (20.08.2022)

In the current discussion, the term climate change is often used as a synonym for the ‘anthropogenic climate change’, which means the climate change that is caused by human activities.3Whitmarsh. (2009). What’s in a name? Commonalities and differences in public understanding of “climate change” and “global warming”. Sage Publications. p.404. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0963662506073088., 4Cambridge Dictionary. (2022). Cambridge Dictionary: anthropogenic. Cambridge University Press. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/de/worterbuch/englisch/anthropogenic (20.08.2022). The international policy community also uses the term accordingly, which can be deducted from the definition of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC): “‘Climate change’ means a change of climate which is attributed directly or indirectly to human activity that alters the global atmosphere and which is in addition to natural climate variability observed over comparable time periods.”5United Nations. (1992). United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: Full text of the convention. New York, USA: United Nations Although there were also changes in climate before human existence, the term ‘climate change’ is currently used for the anthropogenic climate change, because the current climate change is significantly more rapid and human activities have been by far the biggest driver of climate change over the last century.6IPCC. (2014). Climate Change 2014 Synthesis Report. p.4-53. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/SYR_AR5_FINAL_full.pdf(22.08.2022) Nevertheless, according to the IPCC definition, the term climate change encompasses more than just the anthropogenic climate change. The resulting negative impacts of the anthropogenic climate change on humanity, nature and the economies are named in the common language as the ‘climate crisis’.7Sobczyk. (2019). How climate change got labeled a ‘crisis’. E&E News. Environment & Energy Publishing. https://web.archive.org/web/20191013224254/https://www.eenews.net/stories/1060718493 (22.08.2022)

The anthropogenic climate change is currently an important topic, because the latest results demonstrate that climate change and its impacts are coming even faster than expected. This is underlined by the increasing occurrence of extreme weather events. Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are accumulating faster in the atmosphere than ever before in the last 800,000 years, and only in the most optimistic scenario of immediate climate protection can the increase in temperature be limited to approximately 1.5°C until the end of the century.8IPCC. (2021). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Summary for Policy-makers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Nevertheless, heat waves, heavy rain events, and droughts will occur more frequently and be devastating; therefore, corporate climate adaptation becomes unavoidable. Hence, climate change is a complex and urgent crisis that challenges humanity without spatial and social boundaries.9Méndez, M. (2020). Climate Change from the Streets. How Conflict and Collaboration Strengthen the Environmental Justice Movement. New Haven, USA: Yale University Press.

In order to minimize the negative consequences of anthropogenic global warming, 195 countries around the world have committed themselves to limit warming to 1.5°C in the “Paris Agreement” under international law.10United Nations. (2015). Paris Agreement. Paris. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf (20.08.2022) Staying below this 1.5°C target requires changes in society, governance, and the economy. Until 2050, the global economy must operate on net zero emissions to go in line with the Paris Agreement. Furthermore, even successful carbon dioxide (CO2) extraction from the atmosphere (negative emissions) has been discussed as a possible climate action.11IPCC. (2021). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Summary for Policy-makers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Consequently, climate change has become a major driver of structural change in the economy. Implementing a sustainable management in companies could be here a good starting point and could also promote the economic success of the company.12Bardt, H., Chrischilles, E., & Mahammadzadeh, M. (2012). Klimawandel und Unternehmen. Wirtschaftsdienst Hamburg, 92 (1), 29-36. , 13Kern, A., Jung, P., & Jung. P. (2021). Mit Nachhaltigkeit gegen den Klimawandel. Controlling & Management Review, 65(3), 24-31. Anthropogenic climate change is one of the most social, political, and economic challenges of the present age.14Berger, S., & Wyss, A. M. (2021). Climate change denial is associated with diminished sensitivity in internalizing environmental externalities. Environmental research letters, 16 (7), 74018.

1.1 History

At the 1972 United Nations Conference in Stockholm, the first science teams were established to study possible future human-induced climate changes in the industrial age. From the science teams, institutions such as the IPCC and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) were developed. Their publications on climate change are still valid today and provide the basis for today’s understanding of climate change. At that time, climate change was already assumed to have long-term global consequences that would threaten the livelihood and well-being of the world’s population. Since 1972, more than 500 international contracts and conventions dealing with the issue of environmental protection have been signed.15Brasseur, G., Jacob, D., & Schuck-Zöller, S. (2017). Klimawandel in Deutschland- Entwicklung, Folgen, Risiken und Perspektiven (1st edition). Springer Spektrum.

1.2 Scientific background

From a scientific view, the anthropogenic climate change is caused by the additional emitted amount of GHGs (e.g., carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide) into the atmosphere, which intensifies the natural greenhouse effect. 16Umweltbundesamt. (2016). Klimawandel. Retrieved on 28/06/2021: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/themen/klima-energie/klimawandel.dringlicher In 2017, this has led to an additional warming of the average earth’s surface temperature of approximately 1°C and an increase of 0.2°C per decade.17 IPCC. (2018). Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above preindustrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. The process began accelerating with industrialization at the end of the 18th century. Particularly, CO2 is released on a large scale by human activities, such as fossil fuel use and deforestation for industrial and agricultural purposes. For example, methane and nitrogen oxide emissions are mainly emitted by livestock farming and nitrogenous fertilizers in agriculture.18 Umweltbundesamt. (2016). Klimawandel. Retrieved on 28/06/2021: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/themen/klima-energie/klimawandel.dringlicher The findings of the nine planetary boundaries by Rockström et al. (2009) describe important ecosystem services and try to numerate their inbalance state. One geoecological dimension of this model is climate change. However, at least three of nine planetary limits have already been exceeded: biodiversity, biogeochemical cycles, and land use.19 Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, A., Chapin, F. S., Lambin, E., Lenton, T. M., Scheffer, M., Folke, C., Schnellnhuber, H.J., Nykvist, B., de Wit, C. A., Hughes, T., van der Leeuw, S., Rodhe, H., Sörlin, S., Snyder, P.K., Costanza, R., Svedin, U., Falkenmark, M., Karlberg, L., Corell, R. W., Fabry, V. J., Hansen, J., Walker, B., Liverman, D., Richardson, K., Crutzen, P., & Foley, J. (2009). Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for Humanity. Ecology and Society, 14(2), 32-65. For example, phosphorus and nitrogen cycles have been extremely changed by the excessive use of fertilizers in agriculture.20Potsdam-Institut für Klimafolgenforschung. (2015). Vier von neun “planetaren Grenzen” bereits überschritten. Retrieved on 28/06/2021: https://www.pik-potsdam.de/de/aktuelles/nachrichten/vier-von-neun-planetaren-grenzen201d-bereits-ueberschritten[/mfn| These dimensions of geoecological systems point out safe operating areas.20 Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, A., Chapin, F. S., Lambin, E., Lenton, T. M., Scheffer, M., Folke, C., Schnellnhuber, H.J., Nykvist, B., de Wit, C. A., Hughes, T., van der Leeuw, S., Rodhe, H., Sörlin, S., Snyder, P.K., Costanza, R., Svedin, U., Falkenmark, M., Karlberg, L., Corell, R. W., Fabry, V. J., Hansen, J., Walker, B., Liverman, D., Richardson, K., Crutzen, P., & Foley, J. (2009). Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for Humanity. Ecology and Society, 14(2), 32-65. , 21 Steffen, W., Richardson, K., Rockström, J., Cornell, S. E., Fetzer, I., Bennett, E. M., Biggs, R., Carpenter, S. R., de Vries, W., de Witt, C. A., Folke, C., Gerten, D., Heinke, J., Mace, G. M., Persson, L. M., Ramanathan, V., Reyers, B., & Sörlin, S. (2015). Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science, 347 (6223). In particular, climate change is the next highrisk factor measured by the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere of 408 parts per million in 2018, with a continuously rising trend.22 Nelles, D., & Serrer, C. (2018). Kleine Gase – große Wirkung: Der Klimawandel (1st edition). Friedrichshafen, Germany: KlimaWandel GbR. By contrast, the estimated zone of uncertainty is between 350–450 parts CO2 per million 23Potsdam-Institut für Klimafolgenforschung. (2015). Vier von neun “planetaren Grenzen” bereits überschritten. Retrieved on 28/06/2021: https://www.pik-potsdam.de/de/aktuelles/nachrichten/vier-von-neun-planetaren-grenzen201d-bereits-ueberschritten; thus, this factor is likely to also be exceeded soon. The consequences of climate change have been increasingly considered in recent years. For example, extreme weather conditions, such as droughts and heavy precipitation, have become more frequent.24Umweltbundesamt. (2016). Klimawandel. Retrieved on 28/06/2021: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/themen/klima-energie/klimawandel.dringlicher This has led to higher uncertainties in global supply chains and has forced companies to consider climate change-induced risks in their management.

2 Industry’s role as a driver of climate change

Companies both influence and are influenced by the phenomenon of climate change: On the one hand, they are among the polluters; on the other hand, their businesses are increasingly threatened by climate risks. The changing climate conditions are already creating pressure to adapt, and this pressure will continue to grow in the future.25 Ott, H. E., & Richter, C. (2008). Anpassung an den Klimawandel- Risiken und Chancen für deutsche Unternehmen. Wuppertal Papers (171). This is particularly of interest for companies, as it presents both opportunities and risks from which certain measures can be derived. These aspects will be discussed in the following chapter, partly supported by best-practice examples. Industrialization has been the origin of global economic growth, but the industrial sector in general acts as a big contributor to climate change because of the increasing GHG emissions.26 Günther, E., & Nowack, M. (2008). CO2-Management von Unternehmen. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer-Verlag.

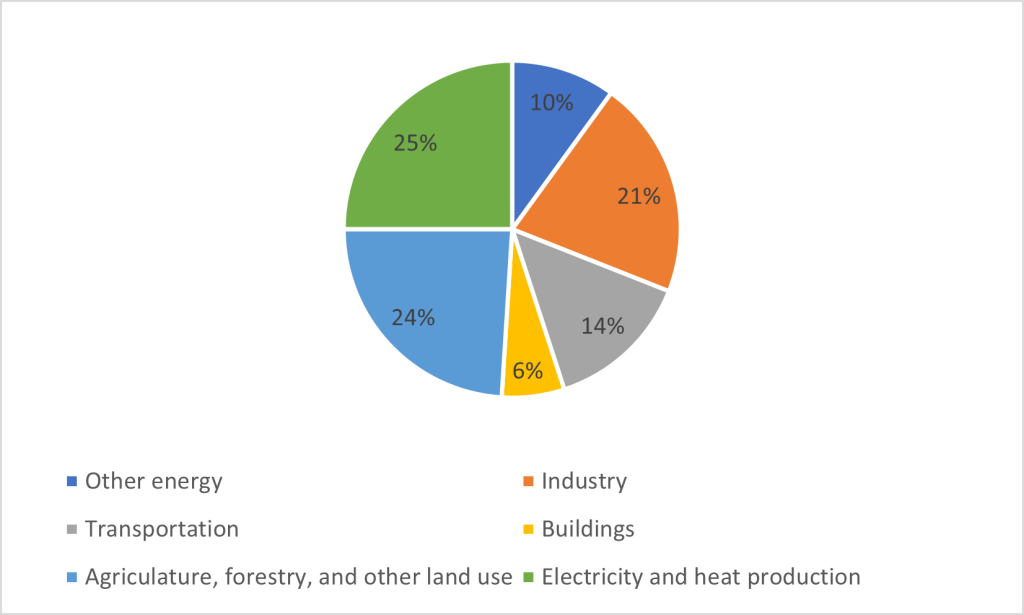

According to the IPCC, the industrial subsector emitted more global GHG emissions than the transportation and building sectors in 2010 (Figure 1). Although energy supply has been the sector with the highest GHG consumption of 25%, this cannot be entirely separated from industry, as they use much of the electricity from the energy supply for their heat and conversion processes.28 Ott, H. E., & Richter, C. (2008). Anpassung an den Klimawandel- Risiken und Chancen für deutsche Unternehmen. Wuppertal Papers (171).

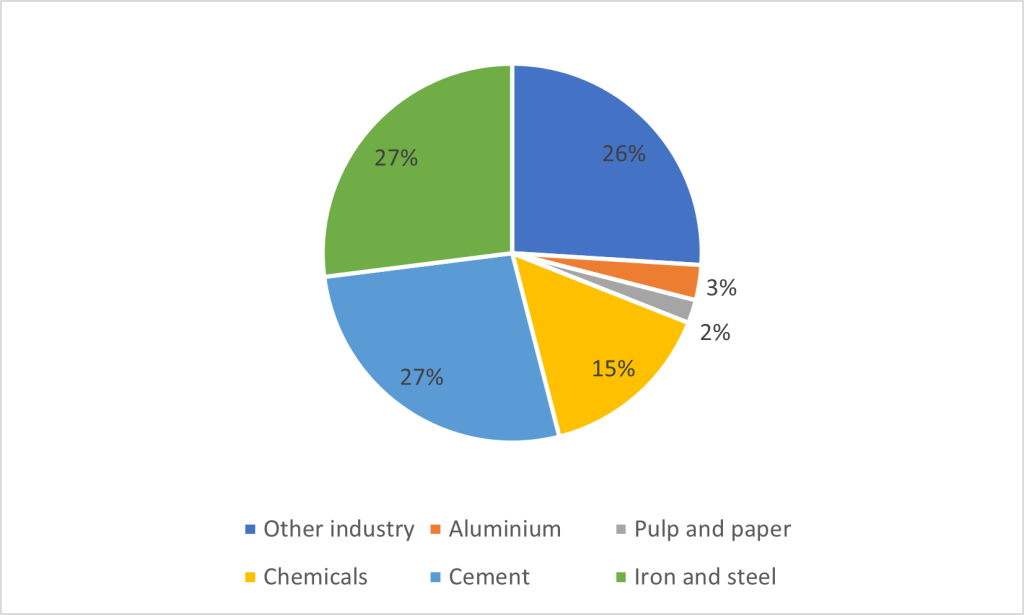

In 2019, approximately 76% of industrial emissions is CO2, which has mainly been produced by cement, iron, and steel production (Figure 2). Numerous heavy industries need high-temperature heat for their production, which is mainly generated with fossil fuels. In a less carbon-intensive way, for example, with electricity, generating this high-temperature heat is more difficult. Additional alternative sources, such as hydrogen from renewable electricity or electric resistance heating from renewable sources, already exist but still depend upon further research and development. Other industries, such as iron and steel production, produce GHG emissions in their production processes. Hence, their decarbonization requires a new revision of these processes.30 Naimoli, S. J., & Ladislaw, S. (2020). Climate Solutions Series: Decarbonizing Heavy Industry. Retrieved on 17/07/2021: https://www.csis.org/analysis/climate-solutions-series-decarbonizing-heavy-industry

Emissions in cement production result from fuel combustion and calcination reactions. Although fuel emissions can be diminished by more energy-efficient processes and changes in fuels, emissions generated from calcination are unavoidable. These can only be lessened through a reduced demand for cement and improvements in the material. Other possible reduction approaches include new technology solutions, such as using zero-carbon energy sources, creating product innovations, using CO2 capture and storage, and making improvements in process efficiency.31 IPCC. (2014). AR5 Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK and New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. However, the heavy industries and potential changes within this sector face problems regarding big investments in technologies and innovations because the sector often operates on small margins, which makes access to capital very difficult. However, the industrial subsector is diverse; therefore, no single solution exists for reducing emissions across all heavy industries. The development of new processes and materials also needs efforts from political actors to ensure the economic competitiveness of decarbonized options.32 Naimoli, S. J., & Ladislaw, S. (2020). Climate Solutions Series: Decarbonizing Heavy Industry. Retrieved on 17/07/2021: https://www.csis.org/analysis/climate-solutions-series-decarbonizing-heavy-industry To transparently monitor emissions, companies are increasingly encouraged to use carbon accounting tools.

3 Corporate carbon accounting

Quantifying and managing the emissions of CO2 and other gases contributing to the greenhouse effect at the corporate level has become the most representative principle among sustainability accounting practices.33 Schaltegger, S., & Csutora, M. (2012). Carbon accounting for sustainability and management. Status quo and challenges. Journal of Cleaner Production, 36, 1–16. A broad understanding exists of which management activities are included by the emission-based calculation. A comprehensive definition is given by Gibassier and Schaltegger as “[…] the recognition, the non-monetary and monetary evaluation and the monitoring of GHG emissions on all levels of the value chain […].”34Gibassier, D., & Schaltegger, S. (2015). Carbon management accounting and reporting in practice. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 6(3), 340–365.

In general, two perspectives are taken when talking about accounting for GHG emissions: a non-monetary (also known as physical) and a monetary focus. The first understanding measures and quantifies the physical amount of GHGs a company emits into the atmosphere, also referred to as GHG inventory or carbon footprint. The monetary assessment is usually linked to evaluating emerging risks due to changes in regulations, polices, or markets.35 Stechemesser, K., & Guenther, E. (2012). Carbon accounting: a systematic literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 36, 17–38. Transaction costs that are involved in implying mitigation or adaption strategies due to climate change, which is called “climate change accounting,” can also be considered.36 Schaltegger, S., Zvezdov, D., Günther, E., Csutora, M., & Etxeberria, I. (2015). Corporate Carbon and Climate Change Accounting: Application, Developments and Issues. In S. Schaltegger, D. Zvezdov, E. Günther, M. Csutora, & I. Etxeberria (Ed.), Corporate Carbon and Climate Accounting (1st ed., pp.1-27). Switzerland: Springer.

Furthermore, the climate accounting process on a corporate level is usually extended to a management or controlling approach that applies the classical cycle of controlling. The iterative process includes, in particular, the formation of key performance indicators to achieve comparability over various time periods, definition of reduction targets for variance analysis, determination of drivers, and, possibly, external verification.37 Schaltegger, S., Zvezdov, D., Günther, E., Csutora, M., & Etxeberria, I. (2015). Corporate Carbon and Climate Change Accounting: Application, Developments and Issues. In S. Schaltegger, D. Zvezdov, E. Günther, M. Csutora, & I. Etxeberria (Ed.), Corporate Carbon and Climate Accounting (1st ed., pp.1-27). Switzerland: Springer. , 38 Günther, E. & Stechemesser, K. (2010). Carbon Controlling. Controlling & Management, 54(1), 62–65. In this respect, anthropocentric emissions are understood as resources or constraints that need to be managed to ensure a company’s success.39 Schaltegger, S., & Zvezdov, D. (2015). Decision Support Through Carbon Management Accounting—A Framework-Based Literature Review. In S. Schaltegger, D. Zvezdov, E. Günther, M. Csutora, & I. Etxeberria (Ed.), Corporate Carbon and Climate Accounting (1st ed., pp.27-45). Switzerland: Springer.

Most companies release not only CO2 into the atmosphere but also other GHGs. The term carbon accounting usually includes all GHGs, as they are converted into CO2 equivalents (CO2e) so that one standardized accounting unit is used to achieve comparability.40 Ranganathan, J., Corbier, L., Bhatia, P., Schmitz, S., Gage, P., & Oren, K. (2004). The greenhouse gas protocol: a corporate accounting and reporting standard (revised edition). Washington DC, USA: World Resources Institute and World Business Council for Sustainable Development. Moreover, carbon accounting at the company level can also be based on a product or project level instead of considering all business activities.41Gibassier, D., & Schaltegger, S. (2015). Carbon management accounting and reporting in practice. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 6(3), 340–365. Life cycle assessment is usually applied to products. It involves analyzing the environmental impact of a product’s entire life cycle (see Sustainable Production Wiki).42 Csutora, M., & Harangozo, G. (2017). Twenty years of carbon accounting and auditing – A review and outlook. Society and Economy, 39(4), 459-480. In general, quantifying corporate carbon footprints is the most adopted practice of carbon management at the organizational level. It serves as the basis for financial valuation; this will be described in detail in the next sections.43 Stechemesser, K., & Guenther, E. (2012). Carbon accounting: a systematic literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 36, 17–38. , 44 Brander, M., & Ascui, F. (2015). The Attributional-Consequential Distinction and Its Applicability to Corporate Carbon Accounting. In S. Schaltegger, D. Zvezdov, E. Günther, M. Csutora, & I. Etxeberria (Ed.), Corporate Carbon and Climate Accounting (1st ed., pp.99-121). Switzerland: Springer.

3.1 Standards and norms of carbon accounting

When companies want to calculate the GHG emissions of their activities, the use of established and highly recognized standards or norms is recommended. The most common methodical principles for GHG monitoring are defined by ISO norm 14064-1 and the Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard of the Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHG Protocol 2004).45 Schaltegger, S., Zvezdov, D., Günther, E., Csutora, M., & Etxeberria, I. (2015). Corpo-rate Carbon and Climate Change Accounting: Application, Developments and Issues. In S. Schaltegger, D. Zvezdov, E. Günther, M. Csutora, & I. Etxeberria (Ed.), Corporate Carbon and Climate Accounting (1st ed., pp.1-27). Switzerland: Springer. , 46 Csutora, M., & Harangozo, G. (2017). Twenty years of carbon accounting and auditing – A review and outlook. Society and Economy, 39(4), 459-480. The GHG Protocol emerged internationally as the de facto standard for companies, as more than 90% of Fortune companies use the standard for reporting.47 Greenhouse Gas Protocol (2021). We set the standard to measure and manage emissions. Retrieved on 25/08/2021: https://ghgprotocol.org/#3 , 48 Deutsches Global Compact Netzwerk. (2017). Einführung Klimamanagement – Schritt für Schritt zu einem effektiven Klimamanagement in Unternehmen. Retrieved on 17/08/2021: https://www.globalcompact.de/migrated_files/wAssets/docs/Umweltschutz/Publikationen/001-Einfuehrung-Klimamanagement-DGCN_web.pdf Both standards share many similar requirements and only differ slightly from each other, as shown in Table 1.

| DIN EN ISO 14064-1 | GHG protocol | |

| Publisher | ISO | WBCSD&WRI |

| Type | International Norm | De-facto industry standard |

| Date | 2006 | Corporate Standard (2004), Corporate Value Chain (Scope 3) Standard (2011) |

| Principles | Relevance, completeness, consistency, accuracy, and transparency | Relevance, completeness, consistency, accuracy, and transparency |

| GHG | CO2, CH4, N2O, SF, HFCs, PFCs, and NF3 | CO2, CH4, N2O, SF, HFCs, and PFCs |

| Organizational boundaries | Control or equity share | Control or equity share |

| Operational boundaries | Emissions are divided in three parts: direct emission, energy indirect emission, and other indirect emissions. | Emissions are divided in three parts: direct emission, energy indirect emission, and other indirect emissions. |

| Mandatory operations | Determination of which indirect emissions to include in GHG inventory | Corporate Standard (Scope 1–2) Corporate Value Chain Standard (Scope 1–3) |

| Verification | External verification | No external verification |

In addition, other methods which may support companies in their carbon accounting need to be mentioned here. In recent years, the idea of the so-called Ecological Handprint emerged. The Ecological Handprint approach is targeted at organizations looking to quantify and communicate the ecological benefits of their products, services or technologies. Complementary to the Ecological or Carbon Footprint, the Ecological Handprint strives to provide a more holistic picture of a firm’s product by calculating reduced emissions of a specific product compared to a baseline product.53Ergene, S. & Banerjee, S. B.; Hoffman, A. J. (Un)Sustainability and Organization Studies: Towards a Radical Engagement. Organization Studies 42 (8), 1319-1335 (2021). Thus, environmental benefits of a product or service can be identified.54Ergene, S. & Banerjee, S. B.; Hoffman, A. J. (Un)Sustainability and Organization Studies: Towards a Radical Engagement. Organization Studies 42 (8), 1319-1335 (2021). The idea is to communicate and to assess the positive climate impacts of products and therefore to extend corporate sustainability. Not only in terms of carbon accounting, but also other benefits can result from the implementation of the Ecological Handprint.

The choice of standard depends on the purpose for which the company’s GHG emissions are calculated. The key criteria for this decision are reporting and verification requirements for gaining access to several GHG programs. This is further explained in the third step in applying carbon management accounting (see 3.2, step 3). The next sub-chapter presents guidance to establish a GHG inventory in conformity with the standard ISO 14064-1 and the GHG protocol.

3.2 Guidance for applying carbon management accounting

Assuming that no uniform accounting method was used, Gao and co-authors (2014) developed a four-step guidance for calculating an organizational footprint. This approach works for both standards and is very useful for companies when considering how GHG accounting can be managed.

The following section first explains the five principles of carbon accounting and then presents the balancing approach step by step.55 Schaltegger, S., Zvezdov, D., Günther, E., Csutora, M., & Etxeberria, I. (2015). Corporate Carbon and Climate Change Accounting: Application, Developments and Issues. In S. Schaltegger, D. Zvezdov, E. Günther, M. Csutora, & I. Etxeberria (Ed.), Corporate Carbon and Climate Accounting (1st ed., pp.1-27). Switzerland: Springer. Before applying accounting methodology, the right course of reliability and credibility should be set.56 Ortas,E., Gallego-Álvarez,I., Álvarez,I. & Moneva, J.M. (2015). Carbon Accounting: A Review of the Existing Models, Principles and Practical Applications. In S. Schaltegger, D. Zvezdov, E. Günther, M. Csutora, & I. Etxeberria (Ed.), Corporate Carbon and Climate Accounting (1st ed., pp.77-99). Switzerland: Springer. Therefore, gaining a GHG inventory requires following five principles that serve as a doctrine disclosing a company’s true GHG situation. The five criteria—transparency, relevance, completeness, consistency, and accuracy—are based on the generally accepted accounting principles for financial reporting. They are commonly accepted, as they are demanded by both standards.57 Schaltegger, S., Zvezdov, D., Günther, E., Csutora, M., & Etxeberria, I. (2015). Corporate Carbon and Climate Change Accounting: Application, Developments and Issues. In S. Schaltegger, D. Zvezdov, E. Günther, M. Csutora, & I. Etxeberria (Ed.), Corporate Carbon and Climate Accounting (1st ed., pp.1-27). Switzerland: Springer. 58 Deutsches Global Compact Netzwerk. (2017). Einführung Klimamanagement – Schritt für Schritt zu einem effektiven Klimamanagement in Unternehmen. Retrieved on 17/08/2021: https://www.globalcompact.de/migrated_files/wAssets/docs/Umweltschutz/Publikationen/001-Einfuehrung-Klimamanagement-DGCN_web.pdf

- Transparency: Performing documentation in a comprehensible manner to openly communicate important information and avoid whitewashing

- Relevance: Providing the information necessary for users by choosing the appropriate inventory boundary

- Completeness: Identifying all significant emissions within the defined boundaries

- Consistency: Having information and data that are comparable over time to be trackable

- Accuracy: Performing calculations that are systematic and reasonable

Step 1: Defining the organizational boundaries of accounting

For a relevant GHG balance, the organizational boundaries within which the accounting will be carried out should be defined, especially for multinational companies with complex organizational structures. The organizational parts included in the inventory should generally be based on the framework of financial reporting and thus include the same fields of activities and subsidiaries. Unlike financial reporting, however, climate reporting ideally expands to consider the major sources of GHG emissions of the upstream and downstream supply chains, which are usually not a part of financial accounting.59 WWF Deutschland & Carbon Disclosure Project. (2014). Vom Emissionsbericht zur Klimastrategie. Grundlagen für ein einheitliches Emissions- und Klimastrategieberichtswesen. Klimareporting.de.

The equity share or control approach is generally suggested. The equity share approach allocates the emissions of the company proportionately according to the share of the equity investment. This should be aligned with the company’s percentage of ownership of the operation. As the name of the control approach indicates, it takes all the emissions into account over which a company has control. Control can be further defined under operational or financial prospects.60 Ranganathan, J., Corbier, L., Bhatia, P., Schmitz, S., Gage, P., & Oren, K. (2004). The greenhouse gas protocol: a corporate accounting and reporting standard (revised edition). Washington DC, USA: World Resources Institute and World Business Council for Sustainable Development.

Step 2: Classification of emissions on an operational basis

In the next step, the origin of GHG emissions is identified to further determine the sources that will be quantified. The GHG Protocol divides company-related emissions into three scopes distinguished by direct and indirect emissions. By definition, the indirect GHG emissions of one company are always also the direct emissions of another company.61 Ranganathan, J., Corbier, L., Bhatia, P., Schmitz, S., Gage, P., & Oren, K. (2004). The greenhouse gas protocol: a corporate accounting and reporting standard (revised edition). Washington DC, USA: World Resources Institute and World Business Council for Sustainable Development. , 62 WWF Deutschland & Carbon Disclosure Project. (2014). Vom Emissionsbericht zur Klimastrategie. Grundlagen für ein einheitliches Emissions- und Klimastrategieberichtswesen. Klimareporting.de. This delimitation defines the clear accounting boundaries of different operational parts of the value chain to avoid double counting.

| Scope 1: Direct GHG emissions | All direct emissions resulting from an organization’s own business activities. They are subject to scrutiny by the company as they come from owned or controlled sources and are emitted in the company’s own facilities. |

| Scope 2: Electricity indirect GHG emissions | GHG emissions from the generation of energy purchased and consumed by the company. |

| Scope 3: Other indirect GHG emissions | All other indirect GHG emissions resulting from upstream and downstream business activities. Emissions indirectly caused through the purchase of all kinds of goods and services. |

As shown in Table 1, quantifying Scope 3 emissions is not mandatory when adopting both standards. However, depending on the industry sector, Scope 3 can be very significant in revealing a company’s true climate impact. On average, Scope 3 emissions account for 40% of a company’s GHG inventory, as shown in Table 3. It is based on the data of 145 companies from the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), an initiated NGO, to which 2,500 companies report their GHG emissions on a regular basis.64 Carbon Disclosure Project (2009). Carbon Disclosure Project – The Carbon Chasm. Based on Carbon Disclosure Project 2008 responses from the world’s 100 largest companies. https://www.wwf.de/fileadmin/fm-wwf/Publikationen-PDF/CDP-The-Carbon-Chasm.pdf Hence, identifying the first emission focal points within the value chain is generally recommended to further decide which scopes should be definitely considered.65 WWF Deutschland & Carbon Disclosure Project. (2014). Vom Emissionsbericht zur Klimastrategie. Grundlagen für ein einheitliches Emissions- und Klimastrategieberichtswesen. Klimareporting.de. Moreover, the types chosen of GHGs should cover the six named in the Kyoto Protocol, which are considered the ones with the highest global warming potential and occurrence: carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), hydrofluorocarbons, perfluorocarbons, and sulfur hexafluoride (SF6).66 UNFCCC (1997). Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Retrieved on 17/08/2021: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/kpeng.pdf The ISO norm 14064–1 also takes nitrogen trifluorides (NF3) into account.

Step 3: Calculating the carbon footprint

The third step requires an accurate collection of the activity data defined in the previous steps and the determination of standard emission factors.67 Gao, T., Liu, Q., & Wang, J. (2013). A comparative study of carbon footprint and assessment standards. International Journal of Low-Carbon Technologies, 9(3), 237-243. An emission factor specifies the GHG intensity of an action in CO2e. The carbon content relies on the included processes and therefore varies among countries or sectors. However, for ordinary economic activities, several standard emission factors have been published (e.g., the GHG protocol itself, DEFRA, GEMIS, or ProBas).68 WWF Deutschland & Carbon Disclosure Project. (2014). Vom Emissionsbericht zur Klimastrategie. Grundlagen für ein einheitliches Emissions- und Klimastrategieberichtswesen. Klimareporting.de. The carbon footprint is then typically calculated by multiplying the consumption data (e.g., the distance driven by a car in km) by the suitable emission factor (e.g., the quantity of CO2 released per km driven by a car).69 Ranganathan, J., Corbier, L., Bhatia, P., Schmitz, S., Gage, P., & Oren, K. (2004). The greenhouse gas protocol: a corporate accounting and reporting standard (revised edition). Washington DC, USA: World Resources Institute and World Business Council for Sustainable Development.

Step 4: Reporting and verifying carbon footprints

The establishment and reporting of a company’s GHG inventory can be voluntary or mandatory. Some countries have implemented a legal obligation to report GHG emissions and/or climate strategies for specific sectors or groups of companies. Since the introduction of EU ETS production, facilities in energy-intensive industries and air traffic must disclose their direct (Scope 1) emissions.70 WWF Deutschland & Carbon Disclosure Project. (2014). Vom Emissionsbericht zur Klimastrategie. Grundlagen für ein einheitliches Emissions- und Klimastrategieberichtswesen. Klimareporting.de. Regulatory requirements, also regarding the standard and reporting formats, differ nationally. Hence, they should be checked in their respective countries, especially for subsidiaries.

Beyond the direct regulatory obligations are a number of indirect motives for voluntary reporting. It offers access to verification and GHG programs, such as carbon performance ratings, GHG registries, and trading programs, which may lead to competitive advantages and credits.71Ranganathan, J., Corbier, L., Bhatia, P., Schmitz, S., Gage, P., & Oren, K. (2004). The greenhouse gas protocol: a corporate accounting and reporting standard (revised edition). Washington DC, USA: World Resources Institute and World Business Council for Sustainable Development. The CDP is the most influential rating for investors that provides information on the quality of a company’s disclosure and its contribution to mitigating climate change.72 DIN e.V. (Hrsg) (ISO 14064-1:2018). Treibhausgase – Teil 1: Spezifikation mit Anleitung zur quantitativen Bestimmung und Berichterstattung von Treibhausgasemissionen und Entzug von Treibhausgasen auf Organisationsebene. , 73 Csutora, M., & Harangozo, G. (2017). Twenty years of carbon accounting and auditing – A review and outlook. Society and Economy, 39(4), 459-480. As already revealed in the definition, carbon accounting is not limited to recording emissions; it also involves further establishing reduction targets and a climate strategy. The deduction of a corporate carbon strategy will be addressed in more detail in the next chapter (see 4.3. Climate Changes as an Opportunity for Companies).

4 Climate change as an opportunity for companies

Climate change not only brings risks to the economy and companies but also creates new market potential and opportunities. These opportunities and possible reactions will be examined and evaluated in more detail. In 2008, a report by the Wuppertal Institute predicted that adaptation measures could become a new business area and open up new opportunities for companies.74 Günther, E., & Nowack, M. (2008). CO2-Management von Unternehmen. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer-Verlag. Over 13 years later, according to GreenTech Atlas 2021, this statement can be occupied in numerical terms. The German economy will benefit from emerging markets for environmental technologies because they will have an annual growth rate of 8% in the next ten years and thereby even exceed the annual growth rate of 7% forecast for the world economy.75 Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz und nukleare Sicherheit. (2021). Green-Tech Atlas 2021: Deutsche Wirtschaft profitiert von wachsenden Märkten für Um-welttechnologien. Retrieved on 12/08/2021: https://www.bmu.de/pressemitteilung/greentech-atlas-2021-deutsche-wirtschaft-profitiert-von-wachsenden-maerkten-fuer-umwelttechnologien In addition, the climate change risk index underlines this statement by describing the sectors of mechanical engineering and equipment for electricity generation as the most promising in comparison to German industry sectors.76 Bardt, H. (2011). Klima- und Strukturwandel – Chancen und Risiken der deutschen In-dustrie. Forschungsberichte aus dem Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft Köln, No. 57. Furthermore, if the German gross domestic product, the value created in Germany, is divided into climate change-induced chances, neutral position, and negative affected parts in nearly 24%, chances will exceed the risks. Approximately 47% are neutral, and in only 29% of the value creation, the risks predominate the possible chances arising from climate change.77 Bardt, H. (2011). Klima- und Strukturwandel – Chancen und Risiken der deutschen Industrie. Forschungsberichte aus dem Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft Köln, No. 57. This means that more than 71% of the value creation is positive, either positively influenced by climate change or in a neutral position to it.

Hence, various chance risk levels occur between the industrial sectors, but all firms can gain competitive advantages from implementing climate strategies. Furthermore, companies’ risk assessment and mitigation regarding climate-induced issues can gain them competitive advantages over other firms in their sector as investors and other stakeholders begin to expect more transparency. According to an article in the Business Harvard Review, this competitive advantage can be reached within four steps:78 Lash, J., & Wellington, F. (2007). Competitive advantage on a warming planet. Harvard Business Review 85(3), 94-102.

- Measure your carbon footprint.

- Assess your carbon-related risks and opportunities.

- Adapt your business according to those risks and opportunities.

- Do it better than your competitors.

As step 1 and step 2 overlap with the model of Chapter 4.2 Corporate Carbon Accounting and 4.4.2 Climate Risks for Companies, in the following the focus will be on step 3. The adaptation of a business can be subdivided into two different types of corporate reactions to climate change. The first is to tackle emission output at the source and enlarge natural and artificial “sinks” of GHG as mitigation measures, and the second is to adapt the business by increasing its resilience to harmful external effects.79 NASA. (2021). Responding to Climate Change. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://climate.nasa.gov/solutions/adaptation-mitigation/

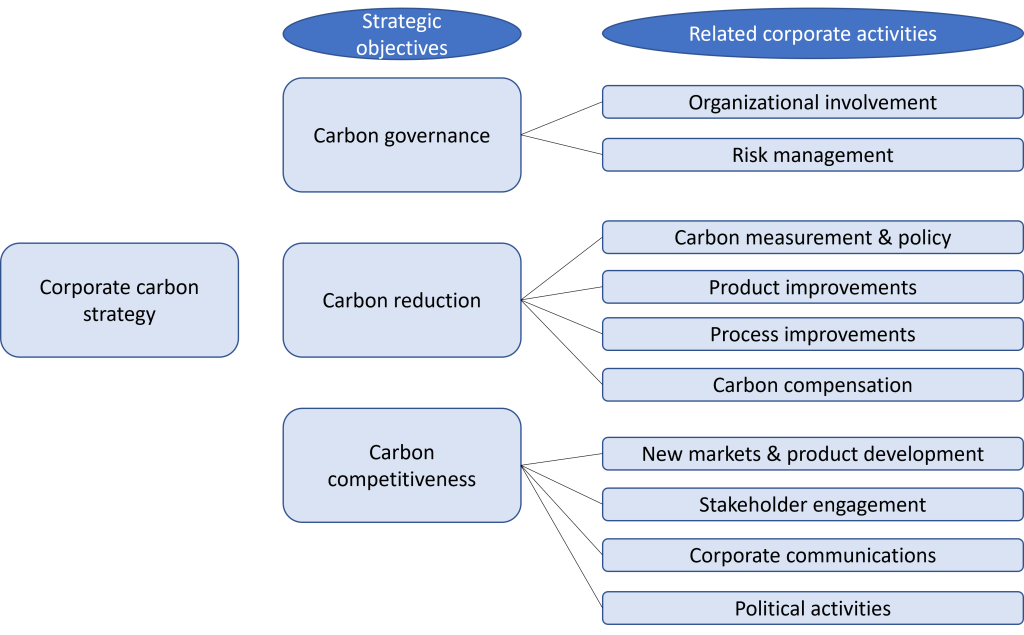

These actions are mostly summarized in a corporate climate mitigation strategy or carbon reduction strategy and consist of measures to manage and preferably decrease corporate GHG emissions. Carbon reduction strategies and corporate climate mitigation strategies are used as synonyms here because they both describe the company’s plan to reduce company-related GHGs. Some authors even take any aspect of corporate action toward climate change into account, although these are dysfunctional to the goal of global reduction of actual GHG emissions. An example is lobbying and stakeholder communication without reported environmental improvement.80 Cadez, S., Czerny, A., & Letmathe, P. (2019). Stakeholder pressure and corporate climate change mitigation strategies. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28, 1-14. We can conclude that little consensus has been reached regarding the scope of corporate climate mitigation strategies.81 Cadez, S., & Czerny, A. (2016). Climate Change mitigation strategies in carbon-intensive firms. Journal of Cleaner Production, 112, 4132-4143. However, the core part of a climate strategy is the definition of a climate target. A company should orient its actions to the globally agreed 2°C threshold for climate change to secure the ability to compete in a changing market environment and assume responsibility for its economic operations.82 Deutsches Global Compact Netzwerk. (2017). Einführung Klimamanagement – Schritt für Schritt zu einem effektiven Klimamanagement in Unternehmen. Retrieved on 17/08/2021: https://www.globalcompact.de/migrated_files/wAssets/docs/Umweltschutz/Publikationen/001-Einfuehrung-Klimamanagement-DGCN_web.pdf Guidance on how a corporate climate target can be developed methodically and scientifically in line with the Paris agreement is provided by the initiative “science-based targets”.83 WWF Deutschland & Carbon Disclosure Project. (2014). Vom Emissionsbericht zur Klimastrategie. Grundlagen für ein einheitliches Emissions- und Klimastrategiebe-richtswesen. Klimareporting.de. In corporate carbon reduction strategies, objectives and allocated corporate activities can be defined. Risk management is mainly addressed through research on corporate adaptation to the physical impacts of climate change.84 Damert, M., Paul, A., & Baumgartner, A.J. (2017). Exploring the determinants and long-term performance outcomes of corporate carbon strategies. Journal of Cleaner Production, 160, 123-138.

Among reduction targets, “Carbon neutrality is often seen as the ultimate goal of sustainability with regard to corporate carbon emissions.”86 Schaltegger, S., & Csutora, M. (2012). Carbon accounting for sustainability and management. Status quo and challenges. Journal of Cleaner Production, 36, 1–16. The term refers to achieving a net result of zero CO2 emissions, which basically means that the amount of climate-damaging gases emitted into the atmosphere is not increased by a company’s business, products, or services. Thereby, attention should be paid to first avoid and second reduce emissions, and if not otherwise possible, compensate for it elsewhere.87 Umweltbundesamt (2018). Freiwillige CO2-Kompensationen durch Klimaschutzprojekt. Retrieved on 17/08/2021: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/376/publikationen/ratgeber_freiwillige_co2_kompensation_final_internet.pdf Product- and process-related reductions through improvements, as seen in Figure 4, should be prioritized more than carbon compensation in order to have an effective corporate carbon strategy. Compensation is synonymous with carbon offsetting and means to support and invest in environmental projects that capture GHG emissions equivalent to the emissions caused. This is usually done for unavoidable CO2 emissions, as no company can economize without leaving its mark on the environment.88 Schaltegger, S., & Csutora, M. (2012). Carbon accounting for sustainability and management. Status quo and challenges. Journal of Cleaner Production, 36, 1–16.

To name some best practice examples in the field of corporate climate action, Capital compared over 2000 German firms in their corporate climate balances: Zalando (e-commerce), Gardena (machine and industrial technology), and Barmenia (insurances) are named as the three best German firms that could manage to reduce their CO2 emissions by 34%–40.9% in the span of 2016–2019. Particularly important are two facts: These three businesses took Scope 3 emissions into account, and they work in three different sectors. Hence, reduction potentials are dependent not only on the industry sector but more so on the firms’ willingness to change. Gardena and Barmenia reduced their own emissions (Scopes 1 and 2) by one-third in comparison to their turnover.89 Von Zepelin, J. (2021). Deutschlands klimabewusste Unternehmen. Retrieved on 21/08/2021: https://www.capital.de/wirtschaft-politik/deutschlands-klimabewusste-unternehmen In particular, Barmenia could reduce its emissions effectively by switching to district heating by the Wuppertaler Stadtwerke in 2019 and further reductions of green electricity consumption in the IT department.90 Barmenia. (2021). Barmenia handelt beim Klimaschutz. Retrieved 26/08/2021: https://www.mynewsdesk.com/de/barmenia/pressreleases/barmenia-handelt-beim-klimaschutz-2883312

5 Climate change as a threat for companies

5.1 Climate risks for companies

Because of the changing climatic conditions and the possible damage that may arise, the occurrence of various risks for companies increases. These risks can be mainly classified into two categories: physical and transitory risks.91 Umweltbundesamt. (2021). Berichterstattung von Unternehmen über klimabezogene Risiken. Dessau-Roßlau, Germany: Umweltbundesamt.

Physical risks can be described as those directly resulting from climate-induced changes in the earth’s ecosystems, such as increasing the frequency and intensity of acute extreme weather events and the long-term chronic changes of mean values of different climate conditions.92 IPCC. (2014). AR5 Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Therefore, economic sectors, such as the agricultural industry, fisheries, forestry, transport, and the tourism industry, are very vulnerable to be affected, which is why they can be seen as climate-sensitive sectors. However, physical effects might be a threat for all kinds of companies, as they can result in financial losses because of damage to assets, disruptions in operations, or complications and shortages in the resource supply.93 Linnenluecke, M., & Griffiths, A. (2010). Beyond Adaptation: Resilience for Business in Light of Climate Change and Weather Extremes. Business & Society, 49(3), 477-511.

Transitory risks are related to the societal shift to a low-carbon economy. These may include regulatory, market price, market, legal, and reputational risks.94 WWF Deutschland & Carbon Disclosure Project. (2014). Vom Emissionsbericht zur Klimastrategie. Grundlagen für ein einheitliches Emissions- und Klimastrategiebe-richtswesen. Klimareporting.de. The different risk types are shown in Table 3, with descriptions and examples.

| Type of Transitory Risks | Description | Examples |

| Regulatory Risks | Due to changes in political and legal frameworksNew requirements for corporate management and reportingIndustries in the focus of governmental regulatory measures, especially energy-intensive industries | Tightening of requirements for production (e.g., inclusion of GHG emissions from the aviation sector in EU ETS(Tightening of requirements for products (e.g., efficiency standards for household appliances) |

| Market Price Risks | Caused by changes in prices for energy, raw materials, loans, insurance, etc. Affected: energy-intensive industries (e.g., metal, construction materials, etc.) | Increase in costs for energy, operating and auxiliary materials, insurance, etc.Increase in transport costs (e.g., as a result of shifts in energy prices) |

| Market Risks | Due to changes in political, legal, or demand-induced framework conditionsAffected: industries that are the focus of government regulation, especially energy-intensive industries | Changes in customer behavior, (e.g., CO2 emissions as purchasing criteria)Technological innovations are being missed (e.g., decline in demand for classic drive concepts) |

| Legal Risks | Possible lawsuits against companies as contributors of climate change (e.g.. civil liability) | Legal regulations of CO2 emissions per vehicle |

| Reputational Risks | Commitment to climate protection is not perceived as sufficient by key stakeholder groupsAffected: Sectors with high public scrutiny (e.g., the energy industry) | Stigmatization as “climate sinners”Withdrawal of the implicit “license to operate”Collapse in demand due to increasing consumer sensitivity |

The importance of transitory risks, in particular, is currently growing. A study of the German Environmental Agency in 2019 pointed out that among the risks that German companies believe could be material to their business development, twice as many transitory risks were named than physical risks. Hence, firms see themselves as more strongly affected by cost increases and sales declines because of a shift to a low-carbon economy.96 Umweltbundesamt. (2021). Berichterstattung von Unternehmen über klimabezogene Risiken. Dessau-Roßlau, Germany: Umweltbundesamt. The pressure from different stakeholder groups on companies differs across sectors. For example, in tourism, automotive, consumer goods, and energy, executives feel the highest pressure. In the first three sectors mentioned above, the pressure is exerted by the consumers. By contrast, pressure in the energy sector comes from the investor and regulator side.97 Coppola, M., Krick, T., & Blohmke, J. (2019). Feeling the heat? Companies are under pressure on climate change and need to do more. Retrieved on 05/08/2021: https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/topics/strategy/impact-and-opportunities-of-climate-change-on-business.html To meet the needs of the key stakeholder groups, companies have to identify, evaluate, and manage possible risks for their business activities.

5.2 Risk management

For successful risk management, both types of risks should be systematically addressed via holistic monitoring and, if necessary, internal adaptation measures should be implemented. The recommendations of the “Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures” (TCFD) can be used as a checklist for this monitoring purpose. To identify the information required by investors, insurers, and lenders to appropriately evaluate climate-related risks and opportunities, the TCFD was founded in 2015 as an international body of the Group of 20 (G20). It developed and published its four recommendations, which refer to the transparent disclosure of governance, strategy, risk management, and metrics with regard to climate risks in the common financial reports.98 Umweltbundesamt. (2021). Berichterstattung von Unternehmen über klimabezogene Risiken. Dessau-Roßlau, Germany: Umweltbundesamt. Because TCFD is supported by the G20, its recommendations are seen as credible by countries and companies worldwide. Its 2020 status report stated that approximately 60% of the world’s 100 largest publicly traded companies support the TCFD, report in line with its recommendations, or do both.99 TCFD. (2020). Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures 2020 Status Report. Retrieved on 11/07/ 2021: https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/60/2020/09/2020-TCFD_Status-Report.pdf To be able to realistically assess individual risk areas, they should be classified and prioritized in terms of their impact and significance for the company. The following questions can provide guidance in classifying risks:100 WWF Deutschland & Carbon Disclosure Project. (2014). Vom Emissionsbericht zur Klimastrategie. Grundlagen für ein einheitliches Emissions- und Klimastrategieberichtswesen. Klimareporting.de.

- Is a short- or long-term effect expected?

- Is a local, regional, national, or international effect to be expected?

- Can the risk be precisely delimited and its extent described?

- What is the probability of the risk occurring?

- Is the risk likely to occur once or frequently?

- Can the risk be actively minimized?

In addition, companies should mind climatic considerations and resulting broader market effects in decision making regarding product development or supply chain management. Statistical risk management needs to become a regular part of corporate processes to fully understand the range of possible direct and indirect scopes of climate risks.101 McKinsey & Company. (2020). Confronting climate risk. Retrieved on 11/07/2021: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability/our-insights/confronting-climate-risk Companies that recognize their risks and take appropriate action through production and product-related innovations can avoid adverse effects on business’ development and achieve competitive advantages. A transparent and comprehensible climate strategy is the logical consequence of a company acting responsibly.102 WWF Deutschland & Carbon Disclosure Project. (2014). Vom Emissionsbericht zur Klimastrategie. Grundlagen für ein einheitliches Emissions- und Klimastrategieberichtswesen. Klimareporting.de.

5.3 Adaptation measures

Adaptation measures are made to try to adjust the firm to climate change and weather extremes, such as heat, storms, and droughts.103 NASA. (2021). Responding to Climate Change. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://climate.nasa.gov/solutions/adaptation-mitigation/ The goal is not to eliminate the cause, the emissions, of the affecting problem, climate change, but rather to reduce the vulnerability to its harmful effects on companies. In particular, in comparison to the research area of climate protection and mitigation measures, effective adaptation measures have been far less investigated.104 Mahammadzadeh, M. (2010). Klimawandel ein Thema mit strategischer Bedeutung für Unternehmen. Uwf 18, 45-51. Companies that are already affected directly or indirectly by climate change are more likely to already have adaptation measures integrated into their carbon reduction strategy. It makes up to one-quarter of the German industry, mostly located in construction, paper and glass industry, logistics, and the chemical sector. Another reason for less adaptation is the missing regulatory incentives for climate protection or knowledge deficits.105 Bardt, H. (2011). Klima- und Strukturwandel – Chancen und Risiken der deutschen Industrie. Forschungsberichte aus dem Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft Köln, No. 57.

Without timely adaptation, additional economic and social costs are expected in the long term.106 Mahammadzadeh, M., Chrischilles, E., & Biebeler, H. (2013). Klimaanpassung in Unternehmen und Kommunen – Betroffenheiten, Verletzlichkeiten und Anpassungsbedarf. Forschungsberichte aus dem deutschen Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft Köln, No. 83. As the vulnerability of different industry sectors or even within one can vary drastically, universal measures that are equally applicable to all cases are difficult to identify. Here are some measures that can be applied in most cases: higher stocks and multisourcing to minimize the risks of potential failures in the supply chain.

5.4 Mitigation measures

Mitigation measures aim to reduce GHG emissions and try to consolidate the emission level in the atmosphere, either by reducing emissions at the source or by increasing the natural “sinks” of GHGs.107 NASA. (2021). Responding to Climate Change. Retrieved on 09/08/2021: https://climate.nasa.gov/solutions/adaptation-mitigation/ Synergies can occur between mitigation and adaptation strategies, although conflicts of objectives cannot be ruled out, such as artificial snowmaking for winter sports to increase resilience with higher water and energy consumption at the same time.108 Mahammadzadeh, M. (2010). Klimawandel ein Thema mit strategischer Bedeutung für Unternehmen. Uwf 18, 45-51.

The mitigation of climate change is more common than adaptation because state-controlled increases occur at the price of energy and CO2 emissions, such as the EU ETS, which limits the allowed amounts of emissions per year in Germany.109 Bardt, H. (2011). Klima- und Strukturwandel – Chancen und Risiken der deutschen Industrie. Forschungsberichte aus dem Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft Köln, No. 57.

These also represent the highest-ranked motivation of firms to decrease their carbon emissions in the German industry.110 Mahammadzadeh, M. (2010). Klimawandel ein Thema mit strategischer Bedeutung für Unternehmen. Uwf 18, 45-51. Nevertheless, internal economic motivations exist, such as the costs of purchasing.111 Cadez, S., Czerny, A., & Letmathe, P. (2019). Stakeholder pressure and corporate climate change mitigation strategies. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28, 1-14. Corporate mitigation measures require carbon accounting measures in advance, as the improvements in the reduction potentials should be monitored and reported to increase the support of the relevant and affected stakeholders in the business environment. For more information on this part, see Chapter 4.2 Corporate Carbon Accounting.

Climate change mitigation and the potential failure of these measures are two of the most challenging global risks.112 World Economic Forum. (2013). Global Risks 2013 – Eigth edition. Retrieved on 13/08/2021: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GlobalRisks_Report_2013.pdf. Nevertheless, climate change mitigation and adaptation measures have to be considered and implemented in parallel to corporate strategy because, even with all the possible mitigations, climate change is unstoppable and without any all-possible adaptation measures would be enough to ensure a stable economy.113Mahammadzadeh, M. (2010). Klimawandel ein Thema mit strategischer Bedeutung für Unternehmen. Uwf 18, 45-51.

6 Drivers and barriers of firm action

The following chapter presents the drivers and barriers of the transformation process toward a climate-neutral economy. To provide a broader overview with different perspectives on the transformation process, we examine climate change from several perspectives. In this context, the legal, social, economic, and technological perspectives are considered.

6.1 Legal perspective

As already mentioned, the latest IPCC report reveals growing scientific evidence that the consequences and risks of the global climate crisis will be severe.114IPCC. (2021). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Summary for Policy-makers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. As a result, the necessity of establishing effective control mechanisms to meet climate protection requirements in businesses is increasing. These control mechanisms may contain legal obligations arising from laws, regulations, and standardized principles at the international, European, and national levels. As observed in recent years, the legislature is increasingly taking these climate protection requirements into account.115 IPCC. (2014). AR5 Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK and New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. New rights and obligations have been entered into force; the German Climate Change Act of 2021 is one example. With this act, the German federal government aims to reduce national GHG emissions by 65% of 1990 levels by 2030 and to achieve climate neutrality by 2045. Companies are also affected by this, as the emission levels for the energy, industry, and building sectors are thus reduced by law. Also associated with the Climate Change Act are regular emission monitoring and decarbonization activities, including federal investments in green hydrogen and energy-focused building refurbishments.116 Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung. (2021). Klimaschutzgesetz 2021. Generationenvertrag für das Klima. Retrieved on 17/08/2021: https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/themen/klimaschutz/klimaschutzgesetz-2021-1913672

In addition to national regulations, international agreements have been made, as climate change is a global challenge. The Kyoto Protocol of 1997 is considered the first milestone in international climate policy. The agreement, which entered into force in 2005, sets binding targets under international law for GHGs for the first time. Its main goal was the control of emissions, taking into account the differences in emissions, wealth, and reduction capacity, which particularly implied the reduction measures of industrialized countries. A total of 191 countries ratified it.117 UNFCCC (2021). Paris Agreement – Status of Ratification. Retrieved on 17/08/2021: https://unfccc.int/process/the-paris-agreement/status-of-ratification The succession arrangement of the Kyoto Protocol is the Paris Agreement. Adopted at the UN Climate Conference in Paris in 2015, it entered into force in 2016, with the long-term goal of limiting the increase in global average temperature to 1.5°C. All participating countries approved the development of national climate action plans with so-called “Nationally Determined Contributions,” which are climate protection targets. Global emissions need to peak as soon as possible so that they will be severely reduced afterwards.118 Europäische Kommission (2021). Übereinkommen von Paris. Retrieved on: 05/08/2021: https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/international/negotiations/paris_de. China and the USA, which are currently the world’s biggest CO2 emitters, are participating in the agreement.119 Deutsche Welle (2021). USA und China gemeinsam gegen Klimawandel. Retrieved on 17/08/2021: https://www.dw.com/de/usa-und-china-gemeinsam-gegen-klimawandel/a-57242699 The Paris Agreement represents an important step toward a more climate-friendly global economy. It acts as a bridge between current fields of action and the global goal of climate neutrality by the end of the 21st century and provides a framework for various legal regulations on climate protection. Thus, it has a relevant impact on the actions of German and globally active companies.120 Hoffmann-Much, S. (2020). § 6: Klimaschutzrecht. In W. Kluth, & Smeddinck (Ed.) Umweltrecht (2nd ed., pp. 333-380). Berlin, Germany: Springer. Nevertheless, due to the still increasing GHG emission quantities, many activists have been criticizing the pace of the implementation of the resolutions since 2015.121 Deutsche Welle (2020). Fünf Jahre Pariser Klimaabkommen- eine Bilanz. Retrieved on 17/08/2021: https://www.dw.com/de/fünf-jahre-pariser-klimaabkommen-eine-bilanz/a-55904058

In addition to legislation, climate change is becoming more relevant for international jurisdiction. The courts are particularly concerned with issues of civil liability for climate change. In various countries, lawsuits related to this issue have already taken place or are still pending.122 Kapoor, S., & Keller, M. (2019). Climate Change Litigation – zivilrechtliche Haftung für klimaschädliche Emissionen, BB, 706-712. These court proceedings focus on the civil liability of individual GHG emitters, such as companies, and on the causal relationship between environmental damages and specific emissions.123 Chatzinerantzis, A., & Appel, M. (2019). Haftung für den Klimawandel. Neue Juristische Wochenschrift, 881-886. As a historical judgment with extensive consequences in 2019, the Shell case must be listed. Following the ruling of the District Court of The Hague, one of the largest oil and gas companies must reduce its CO2 emissions by a net of 45% of its 2019 emission levels by 2030. With this, the court upheld the lawsuit of environmentalists, who proclaimed that Shell is responsible for the emissions of 1.6 billion tons of CO2 annually. This was the first time that a company was forced by court to adopt drastic climate protection targets.124 Birschel, A. (2021). Historisches Klima-Urteil: Shell muss CO2-Emissionen reduzieren. Retrieved on 05/08/2021: https://beck-online.beck.de/Dokument?vpath=bibdata%2Freddok%2Fbecklink%2F2019917.htm&pos=2&hlwords=on Therefore, a corporate duty to contribute to the fight against climate change is demanded and could lead to further claims from those affected by climate damage or environmentalists.

6.2 Social perspective

Apart from the legal framework, nongovernmental organizations and social protest movements act as drivers of corporate climate actions. Activism related to climate change began in 1990 and replaced the environmental movement with its dominating issue of nuclear energy at the beginning of the 21st century. Increased public awareness is also reflected in the annual reports of environmental organizations. Since 2005, topics related to climate protection have been regularly at the top of the agenda (e.g., at the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and Greenpeace).125 Roose, J. (2016). Wollen die Deutschen das Klima retten? Mobilisierung, Einstellungen und Handlungen zum Klimaschutz. Forschungsjournal soziale Bewegungen, 25 (2), 89-100. These forms of association and joint commitment are of particular importance for the social change process and increase the pressure on companies and policymakers to take more climate-friendly actions.126 Hoffmann, A. (2000). Die Bedeutung sozialer Netzwerke für gesellschaftliche Veränderungsprozesse. In U. Böde, & E. Gruber (Ed.), Klimaschutz als sozialer Prozess: Erfolgsfaktoren für die Umsetzung auf kommunaler Ebene (1st ed., pp. 131-139). Berlin Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Verlag.

One of the most influential global social movements is Fridays for Future, which is particularly evident in its role as the organizer of global climate strikes.127 Schneider, G., & Toyka-Seid, C. (2021). Das junge Politik-Lexikon. Bonn, Germany: bpb Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung The first global climate strike, with 2.3 million participants in more than 130 countries, took place in March 2019.128 Statista Research Department (2019). Kennzahlen zum 1. globalen Klima-Streik am 15. März 2019. Retrieved on 06/08/2021: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/1064670/umfrage/kennzahlen-zum-1-globalen-klima-streik/ Many companies also recognize the enormous importance of the movement by supporting the Entrepreneurs-for-Future campaign. It is a constantly growing association of currently more than 5,000 companies that support the demands of the students who strike on Fridays.129 Gawellek, M. (2020). Digitale Vernetzung für nachhaltige Geschäftsmodelle – Wie durch Vernetzung das Klima geschützt wird – Einblicke aus der Praxis. In A. Hildebrandt (Ed.), Klimawandel in der Wirtschaft – Warum wir ein Bewusstsein für Dringlichkeit brauchen (1st ed., pp. 189-208). Berlin, Germany: Springer Gabler. The “Fridays for Future” movement, which was introduced in 2018 by the Swedish schoolgirl Greta Thunberg, is originally a protest of students and other young people who are campaigning worldwide for the climate targets agreed in the Paris Agreement.130 Wahlström, M., Sommer, M., Kocyba, P., De Vydt, M., De Moor, J., & Davies, S. (2019). Protest for a Future: Composition, Mobilization and Motives of the Participants in Fridays for Future Climate Protests on 15 March, 2019 in 13 European Cities. Retrieved on 15/08/2021: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334745801_Protest_for_a_future_Composition_mobilization_and_motives_of_the_participants_in_Fridays_For_Future_climate_protests_on_15_March_2019_in_13_European_cities , 131 De Moor, J., Uba, K., Wahlström, M., Wennerhag, M., DeVydt, M., Almeida, P., Gard-ner, B. G., Kocyba, P., Neuber, M., Gubernat, R., Kołczyńska, M., Rammelt, H. P. &, Davies, S. (2020). Protest for a Future II: Composition, Mobilization and Motives of the Participants in Fridays for Future Climate Protests on 20–27 September, 2019, in 19 Cities Around the World. Retrieved on 15/08/2021: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339443851_Protest_for_a_future_II_Composi-tion_mobilization_and_motives_of_the_participants_in_Fridays_For_Future_climate_protests_on_20-27_September_2019_in_19_cities_around_the_world , 132 Neuber, M., Kocyba, P., & Gardner, B. G. (2020). The same, only different. Die Fridays for Future-Demonstrierenden im europäischen Vergleich. Retrieved on 15/08/2021: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344073305_The_same_only_different_Die_Fridays_for_Future-Demonstrierenden_im_europaischen_Vergleich Greta Thunberg, as “a Jeanne d’Arc of ecological awareness”133 Steinfeld, T. (2019). Der bevorstehende Kollaps. Süddeutsche Zeitung, 12. , contributed to shifting climate change away from an abstract phenomenon and an elusive problem to an acute matter for many people.

The result may lead to a changing society with different customer requirements that demand that companies act responsibly and take foresightful actions. Companies committing to climate protection can benefit from this development due to the reinforcement of their internal and external reputation, according to a study of the Fraunhofer Institute of Labour Economics and Organization. By positioning themselves as climate neutral, the surveyed organizations observed an increase in the company’s image, positive coverage in the press and media, and enhanced motivation of their employees.134 Weidemann, M., Renner, T., Reiser, S. (2009). Klimaneutrale Unternehmen in Deutschland Motive, Methoden und Meinungen – eine Unternehmensbefragung (2nd edition). Stuttgart, Germany: FRAUNHOFER Verlag.

Accordingly, the pressure of the environmental movement has brought about a change in corporate actions and communications. In a study conducted in May 2021, the Federal Environment Agency (UBA) investigated whether there is also an awareness of the risks of climate change for the companies themselves135Umweltbundesamt (2021). Management von Klimarisiken in Unternehmen: Politische Entwick-lungen, Konzepte und Berichtspraxis.. The study shows that only about half of the DAX-30-companies report publicly on these risks and very few of the 100 largest companies studied provides information on the resilience of corporate strategy to stronger climate change and the compatibility with an ambitious climate protection policy. Companies addressing climate-related risks see a greater risk in ambitious climate policies (for example, pricing greenhouse gas emissions) than in the actual consequences of climate change. This shows that, although climate change is seen as a problem, it is not appreciated in its urgency. The perception of a lack of awareness can lead to an inhibition of corporate willingness to invest in climate protection activities.

6.3 Economic perspective

The significant and rapid reduction of GHGs, including the formulation of net zero targets for 2050 in line with the Paris Agreement, requires a resolute and consistent long-term strategy of business enterprises to implement these targets.136 Jacob, D., Görl, K., Growth, M., Haustein, K., Rechid, D., Sieck, K., & Wolff, M. (2021). Naturwissenschaftlicher Hintergrund der Erderwärmung: Wo stehen wir zurzeit?. Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftspolitik, 101(5), 330-334. High investment costs for transformation toward more sustainable and climate-friendly structures, processes, and strategies may be barriers to climate action. Moreover, politically enforced climate mitigation measures increase oil and gas prices. The predicted additional costs must be considered in future product development, production methods, markets, and site selection.137 Bardt, H., Chrischilles, E., & Mahammadzadeh, M. (2012). Klimawandel und Unternehmen. Wirtschaftsdienst Hamburg, 92 (1), 29-36. In particular, energy-intensive industries are negatively affected by the increase in energy costs and cannot choose to transfer production sites abroad. This is defined as carbon leakage. To prevent this relocation of production sites into countries with laxer emission constraints, the European Union (EU) gives more shares of free allowances to energy-intensive industries. Therefore, competitiveness is preserved, even when firms have to take part in the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS).138European Commission. (2021). Carbon Leakage. Retrieved on 26/08/2021: https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/ets/allowances/leakage_en

Furthermore, the volatile regulatory framework of the young legal area of climate protection law can inhibit industrial climate protection innovations. Political support is needed to develop markets for the innovative products. Another barrier is the resource and cost-intensive process to determine the economic benefits of environmental innovation, which typically leads to a focus on short-term sustainable innovations.139Wehnert, T., Mölter, H., Vallentin, D., & Best, B. (2019). Klimaschutz-Innovationen in der Industrie. Abschlussbericht. Wuppertal Institut, Wuppertal.

From an economic point of view, there are several drivers that support climate protection innovations. Pursuing the green growth opportunities can create new industries and businesses, for instance the production of wind turbines and energy services in the renewable energy sector.140Zhang, Fan., Deichmann, Uwe. Growing Green: The Economic Benefits of Climate Action. USA: World Bank Publications, 2013. In OECD countries and China, the so called “low-carbon transition” creates new jobs and economic opportunities by requiring high investments. These investments can be interpreted as short to medium costs for avoiding a possible severe future.141Zhang, Fan., Deichmann, Uwe. Growing Green: The Economic Benefits of Climate Action. USA: World Bank Publications, 2013. More simple and short-term activities, like energy saving measures, can increase the economic efficiency directly.142Zhang, Fan., Deichmann, Uwe. Growing Green: The Economic Benefits of Climate Action. USA: World Bank Publications, 2013.

Another driver are state subsidies for research and development that can be used for demonstrative innovations and projects – possibly complemented by consulting services from public authorities.143Wehnert, T., Mölter, H., Vallentin, D., & Best, B. (2019). Klimaschutz-Innovationen in der Industrie. Abschlussbericht. Wuppertal Institut, Wuppertal.

6.4 Technological perspective

In addition to the negatively affected areas, profiteers of protectionist measures in the sense of climate protection exist. Profiteers are the providers of appropriate climate-friendly or energy-efficient technologies. The positive effects are especially large when climate-friendly products can be exported to other countries on such a large scale that the additional domestic value added exceeds the loss of value added due to price increases.144 Bardt, H., Chrischilles, E., & Mahammadzadeh, M. (2012). Klimawandel und Unternehmen. Wirtschaftsdienst Hamburg, 92 (1), 29-36. Financial incentives, such as subsidies for the use of alternative energy, can drive economic and technological transformations. Further important external success factors are the promotion of research and development to drive technological advancement and the regional concentration of science and industrial companies.145 Wehnert, T., Mölter, H., Vallentin, D., & Best, B. (2019). Klimaschutz-Innovationen in der Industrie. Abschlussbericht. Wuppertal Institut, Wuppertal. , 146 Bazzanella, A. (2006). Technologieorientierte Forschung für den Klimaschutz. Chemie Ingenieur Technik, 78 (4), 357-360. Regional innovation systems can create competitive advantages for the location.147 Wehnert, T., Mölter, H., Vallentin, D., & Best, B. (2019). Klimaschutz-Innovationen in der Industrie. Abschlussbericht. Wuppertal Institut, Wuppertal., 148 Riedlinger, K. (2006). Klimawandel und das Förderkonzept „Forschung für den Klimaschutz und Schutz vor Klimawirkungen“. Chemie Ingenieur Technik, 78 (4), 353-356. An innovation policy focused on climate protection in commercial enterprises can become an internal driver against climate change. On the one hand, this helps to achieve the necessary CO2 savings and, on the other hand, to maintain or even promote economic performance.149 Wehnert, T., Mölter, H., Vallentin, D., & Best, B. (2019). Klimaschutz-Innovationen in der Industrie. Abschlussbericht. Wuppertal Institut, Wuppertal.

However, the necessary high investment costs are also a barrier to mitigating climate change from a technological perspective.150 Gawellek, M. (2020). Digitale Vernetzung für nachhaltige Geschäftsmodelle – Wie durch Vernetzung das Klima geschützt wird – Einblicke aus der Praxis. In A. Hildebrandt (Ed.), Klimawandel in der Wirtschaft – Warum wir ein Bewusstsein für Dringlichkeit brauchen (1st ed., pp. 189-208). Berlin, Germany: Springer Gabler. The cost–benefit balance is fundamental in the context of the basic economic questions of climate adaptation.151 Heuson, C., Gawel, E., Gebhardt, O., Hansjürgens, B., Lehmann, P., Meyer, V., & Schwarze, R. (2012). Ökonomische Grundfragen der Klimaanpassung. Umrisse eines neuen Forschungsprogramms. Helmholtz-Zentrum für Umweltforschung Bericht, No.02/2012. Often, the higher investment costs of new technology and innovation become an obstacle to entrepreneurial transformation.152 Markewitz, P., Kuckshinrichs, W., Leitner, W., Linssen, J., Zapp, P., Bongartz, R., Schreiber, A., & Müller, T. E. (2012). Worldwide innovations in the development of carbon capture technologies and the utilization of CO2. Energy & Environmental Science, 5(6), 7281-7305. Nevertheless, cost-effective technologies for a low-carbon economy already exist, but they are not yet used anywhere to the extent and speed needed.153 Bazzanella, A. (2006). Technologieorientierte Forschung für den Klimaschutz. Chemie Ingenieur Technik, 78 (4), 357-360. , 154 Herden, C., Alliu, A.C., Cakici, A., Cormier, T., Deguelle, C., Gambhir, S., Griffiths, C., Gupta, S., Kamani, S.R., Kiratli, Y.-S., Kispataki, M., Lange, G., Moles de Matos, L., Tripero Moreno, L., Betancourt Nunez, H. A., Pilla, V., Raj, B., Roe, J., Skoda, M., Song, Y., Ummandi, P. K., Edinger-Schons, L. (2021). Corporate Digital Responsibility: New corporate responsibilities in the digital age. Sustainability Management Fo-rum, 29(1), 13-29. , 155 Watson, R., Nakicenovic, N., Messner, D., Rosenthal, E., Goldemberg, J., Srivastava, L., & Jiang, K. (2015). Die Herausforderungen des Klimawandels bewältigen: Ein kurzfristig umsetzbares Aktionsprogramm zum Übergang in eine klimaverträgliche Weltwirtschaft. Zeitschrift für Außen- und Sicherheitspolitik, 91-125.