Authors: Tabea Hildebrandt, Jessy Tieu, Andreas Windges

Last updated: October 1st 2023

1 Definition and Relevance

Fashion can be defined as the societal desire for certain clothing styles or trends in a given time period. The products of the fashion industry allow customers to either distinguish themselves individually from society or enable a connection through uniformity.[1],[2] For example, exclusive or rather expensive clothing is seen as a status symbol to differentiate oneself from the less affluent population.[3]

Until the mid-19th century, all garments were created by hand for individuals. New technological advances combined with the ever-increasing proliferation of factories enabled the mass production of clothing. But above all, this circumstance is largely attributed to the standardization of clothing sizes.[4],[5]

Today, the fashion industry is a highly globalized industry with annual revenues of over 1.5 trillion USD and about 60 million employees.[6] As one of the largest industries in the world, it makes a major contribution to the international economy. Based on annual revenues, the clothing industry would rank among the 14 richest countries in terms of gross domestic product.[7] The apparel industry is not only a source of job creation, but also enables skills development, especially for people in poor countries.[8]

The industry consists of three main subsectors: Textile production, fashion manufacturing, and fashion retailing. Textile production revolves around the use of fibers, yarns, and fabrics to produce fashion products. This includes natural or synthetic, sustainable, and high-tech fibers and fabrics.[9] In the following step, these are used for the fashion manufacturing process. The process includes, among other things, the selection of fabrics, washing, and dyeing, as well as cutting and sewing the materials.[10] The last subsector revolves around fashion retail. Here, the manufactured products are made available to retailers for sale to potential customers.9

The products of this industry can be divided into numerous fashion categories. These include clothing, footwear, sportswear, luggage and bags, watches and jewelry, and other fashion accessories. These categories can in turn be assigned to six different fashion segments which are luxury, affordable luxury, premium/bridge, mid-market, value, and discount.7 They can be represented in the form of the so-called “fashion pyramid”. In the fashion pyramid, fashion products are assigned to the categories based on price, quality, and the length of the product life cycle.[11]

2 Fashion’s Impact on Sustainability and its Measurement

The fashion industry is considered one of the most energy-consuming and resource-wasting industries in the world.[12] After the oil industry, it is the largest contributor to global warming.[13] To measure sustainability in this context, the ecological footprint can be used. The ecological footprint is the total area needed to sustain a population or its lifestyle in the long term. This includes water use and the area used for production.[14] The following sections delve into sustainability impact areas of the fashion and textile industry found in literature: resource consumption, working conditions, carbon emissions, hazardous output, and product waste.

2.1 Resource Consumption

A large number of resources is consumed throughout the entire supply chain. The annual water consumption alone amounts to 79 billion cubic meters,6 which corresponds to about 20% of the global water consumption.[15] Of the global water consumption cotton production accounts for 2.6%.13 These numbers are expected to increase by another 50% by 2030.20 After the fruit and vegetable industry, it is the one with the highest water consumption worldwide.[16]

Large quantities of oil are required to produce synthetic fibers. A total of more than 70 million barrels of oil are needed annually.13 The industry is responsible for 1.35% of the annual global consumption of oil, which is even greater than the consumption of Spain.12 Petrochemicals, which include synthetic fibers used in clothing, accounted for 14% of total oil consumption in 2017, making the fashion sector the most oil-intensive industry after the transportation sector. Oil consumption due to petrochemicals is expected to increase by 50% by 2050.12

The energy consumption of the fashion industry is significant. Fast fashion alone accounts for over 2% of global energy consumption.[17] The fashion industry has one of the largest shares of energy consumption of the industrial sector industries.[18]

Currently, 85.2 million hectares of land are used for the production of basic materials, representing 5% of the world’s arable land. The fashion industry is therefore the second largest industry in terms of land use.[19] By 2030, this figure is expected to increase to 115 million hectares, or 7%.6, [20]

Approximately 5 billion animals are used annually for fashion production. Due to the complexity of supply chains, it is difficult to determine whether animal welfare is ensured in each case. Livestock is responsible for 32% of global methane emissions.[21]

2.2 Working Conditions

In 2015, the fashion industry employed 51 million people, representing 1.8% of global employment.[22] Up to 70% of its employees work in sewing and most of them are women.[23] The employers are viewed negatively due to reports about labor rights violations,[24] and their sourcing conditions in predominantly low-wage countries.[25] Workers report human rights violations, threats of job loss, and humiliation. Existing research on workplace harassment suggests that human rights abuses are particularly prevalent in countries where there is no legal recourse for workers and repressive political regimes.[26] Worker reports also indicate threats to human health by constant exhaustion and chronic fatigue.[27] Another problem that studies have addressed is that increases in the minimum wage are followed by increases in workers’ production targets and deductions from workers’ wages and overtime. According to local NGO officials in Bangladesh, the production target of a worker was between 100 and 120 pieces per hour in 2013 and increased to 180-200 pieces per hour after the announcement of a new wage scale, further straining the capacity of workers in the face of extreme work pressure.26 In Bangladesh, a major part of the workforce in the textile sector have working hours between 14 and 16 hours per day.[28] Another industry issue are the workers’ payment. The wage paid to employees is often not enough in comparison with a liveable wage. Often, there is a statutory minimum wage in the countries of production that companies must pay.23 In Bangladesh, for example, the monthly wage in 2015 for garment workers was 68 USD.28 However, this does not usually correspond to a living wage, which is also enshrined by the UN as a human right. The Clean Clothes Campaign (CCC), an international workers’ rights organization, defines the living wage as a full-time monthly wage sufficient to cover costs for pay for food, housing, medical care, clothing, transportation, and education. Another problematic aspect of the employees’ working conditions is the unsafe working environments. One-third of respondents described their working environment as unsafe and unhealthy.[29] The health of the workers is endangered, among other things by the often poor structural condition of the factories. Even after the collapse of the Rana Plaza factory building in Bangladesh in 2013, the structural deficiencies in many factories still exist. Only a fraction of factories is inspected, for example, 27% of the garment factories in Bangladesh. On top of that, there is a lack of willingness or financial resources for remediation of the factories.[30] The unsafe use of chemicals in textile manufacturing can also put factory workers at risk. According to a Swedish study of chemicals used in textile manufacturing 10% of the substances were found to be hazardous to human health.[31] In particular, chemicals from leather tanneries cause severe burns and signs of illness. There is also evidence of increased cancer rates among workers from this sector.[32] As mentioned previously, the garment industry is a female-dominated sector. Although women are overrepresented in these jobs, the opposite is true for management positions.27 Other documented practices of gender discrimination include systematic discrimination (including on the grounds of pregnancy), violence and harassment, limited opportunities for skills development, and career advancement.[33] According to the Asia Foundation Report 2017, child labour still exists in 40% of the documented factories. The dark figure is estimated to be even higher due to the high number of illegal factories.25

2.3 Carbon Emissions

The carbon emissions of the fashion sector are the fifth highest compared to other industries.19 In 2015, emissions already amounted to more than 1.2 billion tons of CO2 per year. This even exceeds the combined values of the aviation and shipping industries.[34] Expressed as a percentage, the sector’s CO2 emissions correspond to a value of approximately 10%.[35]

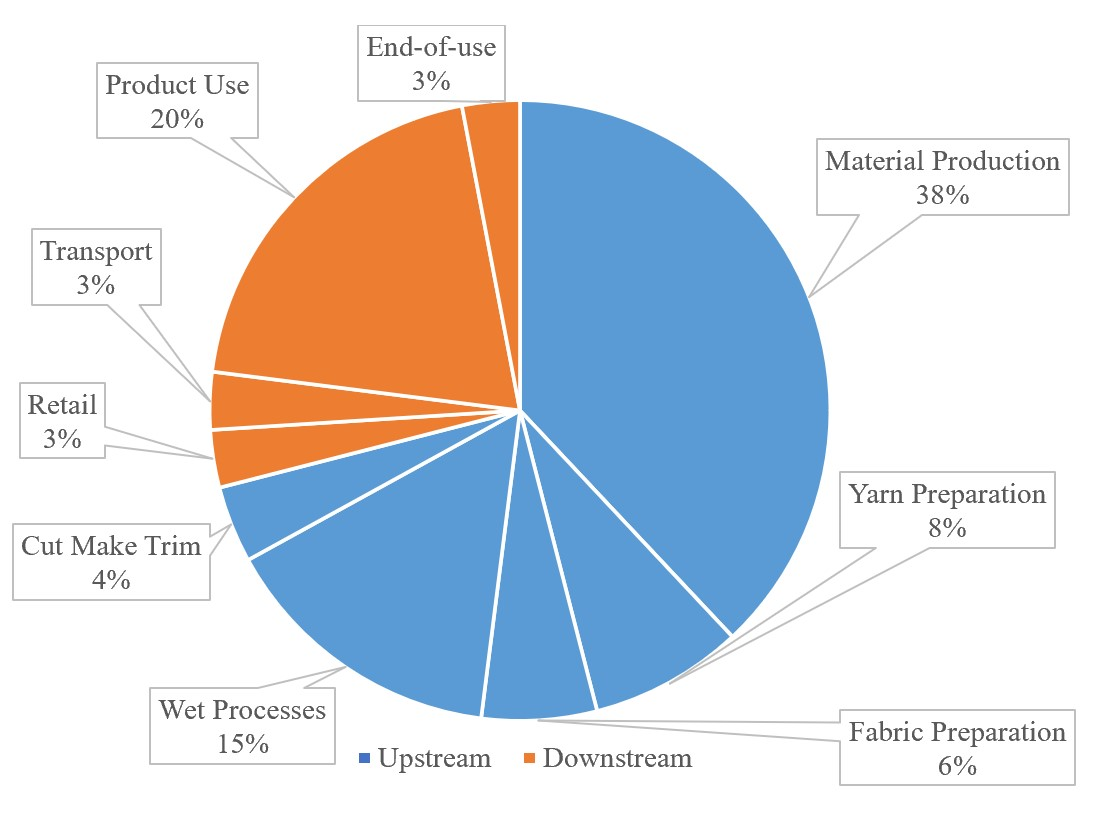

The emissions differ in terms of influence within the supply chain. Around 70% of the fashion industry’s emissions can be attributed to upstream processes. These upstream processes include production, preparation, and the wet processes. The other 30% can be attributed to downstream processes like retail, the product phase, and the end-of-use (see Figure 1).[36]

If emissions remain constant, it can be assumed that these values will increase by more than 50% by the year 2030.[37]

Figure 1: Distribution of Carbon Emissions through the Supply Chain (own illustration according to 36)

2.4 Hazardous Output

In addition to carbon emissions, the fashion industry emits pollutants that harm ecosystems and human health. These impacts vary across different fiber types. While organic fibers rely on pesticides and fertilizers, synthetic fibers release microplastics into the environment. Both water and chemicals are integral to the fiber and textile manufacturing process, resulting in the discharge of hazardous wastewater into the freshwater resources.[38]

During the manufacturing process, more than 15,000 different chemicals are utilized. Concerning financial value, 6% of global pesticide production is allocated to cultivating cotton crops, which serve as the primary source of organic fiber. This allocation entails 16% of insecticide use, 4% of herbicides, growth regulators, desiccants, and defoliants, as well as 1% of fungicides. Agrochemicals are known to cause health issues such as nausea, diarrhea, cancer, and respiratory diseases. This results in neurological and reproductive issues and nearly 1,000 daily deaths. Furthermore, they can negatively affect microorganisms, plants, insects, soil diversity, and fertility.31

Moreover, chemical additives are employed throughout various fiber and textile manufacturing stages. These additives are necessary to enhance textile functions such as flame, water, or antibiotic resistance, as well as for effects like coloring.38 Approximately 27% of global chemical consumption is associated with textile wet processes.[39] The fashion industry is responsible for 20% of global industrial wastewater.[40] The extent of pollution is indicated by factors such as color, temperature, salinity, pH, biological oxygen demand (BOD), chemical oxygen demand (COD), total dissolved solids (TDS), total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP), and non-biodegradable organic compounds. High values of these parameters,[41] along with heavy metals like iron, aluminum, and copper are indicative of textile effluents. Exposure to heavy metals can result in health problems, including bone disorders, carcinogenicity, cancer, kidney failure, brain damage, gastrointestinal diseases, memory issues, and neurotoxicity.[42]

The USEtox model makes chemicals comparable based on their estimated impact on human health and the environment. It employs comparative toxicity units (CTU), which consider disease incidence per kg of emitted chemical. They also include the potentially affected fraction of species integrated over time and area or volume per kg of chemical emitted.31

Wastewater containing 10-45% textile dyes enters aquatic reservoirs with or without proper treatment. Approximately 140,000 tons of textile dyes are discharged as wastewater annually worldwide. In comparison to other industries, the textile industry releases the highest amount of dye into the environment (see Figure 2). This poses health risks to ecosystems and humans, as textile dyes are toxic, carcinogenic, mutagenic, teratogenic, and poorly biodegradable. Furthermore, high dye concentrations in water bodies reduce re-oxygenation potential and impede sunlight penetration, adversely affecting aquatic plants and algae and exacerbating photosynthesis challenges.41

Figure 2: Percentage of Existing Dye Effluents in the Environment Released by Key Industries (own illustration according to 42)

Moreover, textile effluents are the primary microplastic source in aquatic environments. An estimated annual 200,000 to 500,000 tonnes of microplastic fibers, constituting 35% of marine microplastic pollution, originate from synthetic textiles like polyester or nylon. This release often occurs during the wash of synthetic fabrics. Microplastic can also be emitted into the air during garment drying or wear. Ingestion or inhalation of microplastics can lead to false satiation, irritation, and digestive system injuries, potentially causing impaired fitness and reproduction. While the long-term effects of microplastic pollution remain uncertain, the limited degradability of microplastics contributes to their aggregation in natural habitats and their potential breakdown into smaller fragments.38

These environmental consequences are unevenly distributed due to globalization. The demand from developed countries leads to pollution in developing nations where textile manufacturing is concentrated,31 exacerbating clean water shortages in those regions.39

2.5 Product Waste

With the proliferation of the fast fashion business model the amount of clothing produced and discarded has increased sharply.[43] This is why the constant supply of the latest styles is at very low prices.43 Sometimes the lifetime of garments is less than a whole season.[44] In terms of numbers, this means a doubling of global apparel production between 2000 and 2014 and an expected tripling from 2015 to 2050.[45] Similarly, the global annual consumption of textiles from EU households also doubled from 7 to 13 kg per person.[46] Being part of the sector, fashion waste also contributes to 14.9% of global plastic waste of the textile sector, which is the second largest polluting sector after packaging.[47] The fashion industry’s waste originates from different phases of a garment. It is distinguished between waste from manufacturing, pre-consumption waste, and post-consumption waste.[48] Textile manufacturing processes such as weaving or knitting, dyeing, and finishing steps, generate waste in the form of fibers, yarns, and fabrics.48 Depending on the type and design of the garment, fabric width, and surface design studies estimate the fabric overhang for the cutting step to be 10-30%.31 Of the excess materials from clothing manufacturing less than 1% is recycled into new clothing. This represents a material loss worth over 100 billion USD per year.34 Pre-consumer waste also includes what is known as “deadstock.” This name is given to new, unworn garments that are not sold or returned, especially after being purchased online. Estimates from the Netherlands for 2015 put the number of unsold garments at 21 million, which represented 6.5% of the stock.31 Post-consumer textile waste is discarded clothing that has often fallen out of fashion because of poor fabric performance.48 Nearly 60% of the 150 billion garments produced worldwide in 2012 were discarded within a few years of production because the expected life of garments has shortened.31 Of this post-consumer textile waste only about one-third is collected separately for further reuse or recycling.[49] Collected garments that can be reused are often exported from the West to developing countries.31 In such countries, it comes to oversaturated second-hand markets that threaten their own local production or have already replaced it.31 Only about 15% of the non-reused textile waste is recycled.46 Most of the textile waste that is not collected end up in the residual waste.49 Over 66% of all textile waste is landfilled after its use.48 In landfills, the problem is that a large proportion of synthetic textiles does not degrade naturally and ends up as waste in the biosphere.49 This can result in the loss of microbial populations and soil nutrients.48 The alternative to landfilling is the incineration of textile waste, which leads to the release of pollutants, greenhouse gases, and aerosols.48 Even though some energy can be recovered from the products when used clothing is incinerated, it also produces more emissions and air pollutants than reuse or recycling.31

3 Fashion’s Sustainability Measures

This chapter discusses approaches and technologies found in the literature to improve sustainability in the fashion sector. They are grouped into the themes of sustainable fabrics, sustainable manufacturing processes, supply chain simplification, circular model, information transparency, certificates, and labels.

3.1 Sustainable Fabrics

In 2019 the global fiber production amounted to 111 million metric tonnes, and it is anticipated that it will rise to 146 million metric tonnes by 2030.45 Of this global fiber production polyester fibers comprised about 90%, which dominates the world textile market next to cotton.50 As stated by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, the material flows for clothing in 2015 were composed of 97% source material, 2% recycled source material from different industries, and <1% of own circular recycling. The virgin feedstock consists of 63% plastic, 26% cotton, and 11% other materials.34 For the fashion industry to become more sustainable there is the need that fibers and finishes of used textile materials become more ecological and biodegradable or easier recyclable.[50] Hence the fiber choices in the design stage of a garment influence the environmental impact of the resulting product’s whole lifecycle.49 It is estimated that the production of raw materials and further processing by the textile and light industry have the greatest potential for reducing the carbon footprint.45 The environmental profiles of the individual fiber types differ according to their intended use, care, service life, and the treatment of the product post-consumer.49 To achieve more sustainability, it is also relevant to use the desired fiber type in the purest form possible since these are easier to recycle than fiber blends.49 Natural sustainable vegan fabrics are made from cellulose-based fibers obtained from plant-based material.28 If these plants are grown organically, no undesirable chemicals are introduced during cultivation. This reduces the negative impact on the environment.50 The high-water consumption required for growth is one of their disadvantages. Sustainable natural materials derived from animals include protein fibers such as silk and wool,50 as well as vegetable tanned leather. Compared to cotton, materials made of synthetic fibers are more resistant to abrasion, which means they can be used for longer periods of time.49 However, approximately 48 million tons of petroleum are used annually each year for the production of synthetic textile fibers.45 For this reason, the production of polyester, accounts for up to 40% of emissions from the fashion industry.45 Reusing fibers can help reduce this value. Semi-synthetic fibers are made of natural polymers, for example, viscose based on wood cellulose,49 or artificial cellulose fibers like Tencel-Lyocell.45 The advantage of cellulose-based fibers is that if they are produced without any additives, cellulose-based fibers are biodegradable.28 In addition, fibers for textiles can also be extracted from agricultural waste products or inedible plant parts with high cellulose content such as pineapple leaves.45 For the fabric groups examples and their respective advantages are explained in more detail in Table 1.

| Groups of sustainable fabrics | Fabrics | Advantages |

| Natural sustainable clothing fabrics | (Organic)* cotton | As a natural product, it is regeneratively renewable, and degrades completely;[51] is recyclable mechanically without chemical use34 *no use of synthetic chemicals,50 like pesticides and synthetic fertilizers34 |

| Recycled cotton | As a substitute for virgin cotton fibers: reduces the use of agricultural land and environmental impacts from cotton cultivation: pesticides and fertilizer; LCIA results reveal: using 1000 kg of recycled cotton yarns can save about 0.5 ha of agricultural land, 6600 kg of CO2 equivalent, and 2783 m3 of irrigation water[52] | |

| (Organic)* linen | Cultivation requires only small amounts of fertilizer and water and can grow on land that cannot be used for food production34 *no use of synthetic chemicals50 | |

| (Organic)* hemp | Cultivation requires only small amounts of fertilizer and water and can grow on land that cannot be used for food production34 *no use of synthetic chemicals50 | |

| Recycled synthetic sustainable clothing fabrics | Recycled polyester | Fibers are made from used polyester garments, industrial waste, and PET bottles; substituting virgin polyester reduces landfill, energy consumption, and carbon emissions without sacrificing the quality of the material and the products[53] |

| ECONYL® | 100% recycled, of post-use materials from carpets, and factory waste from the textile production34 | |

| Potentially sustainable natural animal fabrics | (Organic)* wool | Relatively long fibers; offer better properties for mechanical recycling34 *no use of synthetic chemicals50 |

| (Organic)* silk Peace Silk / non-violent silk | *no use of synthetic chemicals50 Toxic metals for the degumming process like in conventional silk production is prohibited; no moths get killed to extract the cocoons25 | |

| Vegetable tanned leather | Less toxicity through less heavy metal used in the tanning process; no inorganic substances in the tanning process[54] | |

| Sustainable semi-synthetic clothing fabrics | Lyocell | Made by recycling cotton scraps from factory waste and combining them with wood to produce a new fiber, production solvents are non-toxic and can be kept in a closed loop.34 |

| Piñatex | Replace animal leather with herbal alternatives (plant growing distributes less CO2 emissions than raising animals);[55] use of waste products (pineapple leaf waste)[56] |

Table 1: Examples of Sustainable Fabrics and their Advantages (own table based on 51,34,52,50,53,25,54,55,56)

3.2 Sustainable Manufacturing Processes

Besides using sustainable materials, there are other ways to enhance the sustainability of garments. This section examines approaches in the clothing production process.

Two significant research paradigms aimed at mitigating pre-production waste in the cutting stage of clothing production are Cutting and Packing and Zero-Waste Fashion Design. Cutting and Packing employs optimization algorithms to minimize fabric waste, whereas Zero-Waste Fashion Design employs innovative techniques to make use of all sections of the fabric. Up to 15% of the total fabric can be avoided from being discarded using these methods. Notable designers like Julian Roberts, Timo Rissanen, Holly McQuillan, and Mark Liu have embraced Zero-Waste Fashion Design. However, mass production has not widely been applied to this intricate and time-consuming process. Cutting and Packing has advantages from extensive knowledge and robust algorithms for automated problem-solving. Nevertheless, human intervention remains necessary due to the lack of flexibility in problem definition.[57]

Fabric cutting can be done more efficiently and with less waste using laser technology. It also finds application in marking, welding, engraving, or fading leather and denim, 3D body scanning, and fault detection. By opting for lasers over chemicals, flexibility increases, harmful effects decrease, water usage is avoided,50 pollution and toxic by-products are reduced, and the risk of product damage is minimized. Levi Strauss & Co. has implemented a laser finishing system, resulting in accelerated processes and diminished hazardous inputs and carbon emissions.39

Similarly, Moonlight Technologies has reduced its environmental footprint by integrating plant-based chemistry and non-toxic, biodegradable colorants for dyeing and fabric finishing.40 This eco-conscious approach has been embraced by fashion companies such as Monsoon Blooms, Harris Tweed, and Patagonia. Natural dyes are not only renewable and biodegradable, but they also reduce the toxicity associated with the dyeing process. Another dyeing innovation involves waterless dyeing, a method that eliminates the production of hazardous effluents. DyeCoo technology employs carbon dioxide as a dyeing medium, resulting in a 50% reduction in energy consumption, the reuse of 95% of carbon dioxide used, and faster dyeing compared to traditional methods. However, this approach requires specialized machinery, leading to higher initial investments. Despite this, brands like Nike, Adidas, Gap, and IKEA have adopted this technology. Meanwhile, AirDye involves the transportation of fabrics within jet-dyeing machines using air, consuming 95% less water and 85% less energy compared to conventional processes.39

Enzymes allow for chemical processes at lower temperatures. This reduces processing time, costs, and water and energy usage during desizing, scouring, bleaching, and stone washing. It could potentially lead to a 30-50% reduction in water consumption and 50-60% in water usage and air emissions costs. The benefits of enzymes are their non-toxicity, efficiency, biodegradability, and pollution reduction in textile production. However, challenges from using enzymes arise due to difficulties in their recovery, reuse, and scalability. In addition, there is a need for rigorous monitoring of process parameters and a possibility of irritation or allergies from direct exposure to enzymes.39

Over 80% of microfiber release during washing can be eliminated through the electrofluidodynamic method by coating polyamide fabrics with biodegradable polymers. Textile joining techniques such as adhesive bonding and welding can reduce material consumption and improve recyclability because they do not require sewing threads.46

3.3 Supply Chain Simplification

The global transport system for raw materials and final products across various national borders leads to considerable environmental pollution in the form of CO2 emissions.[58] The selection of regional supplier countries regarding their proximity to end markets can contribute to greater sustainability. The return to regional production locations is also referred to as re- or nearshoring.[59] To achieve sustainability in the fashion industry the entrepreneur should pay attention to social standards and environmental impact at every stage of the product life cycle. A reduction of intermediate producers in the sense of the slow fashion concept can contribute to this. A shortened supply chain allows more transparency about the impact of each step and more direct contact between the actors.25 To truly ensure sustainability fashion brands should collaborate with all stakeholders in the product development process.[60] This is most directly possible if all manufacturing processes are carried out by one company so that it guarantees sustainable practices on its own. The sustainable fashion brand Givn focuses its production sites on Europe. According to its own statement, this enables direct communication with suppliers, in contrast to manufacturing in Asia. In addition, it enables regular condition inspection on-site.[61] Another advantage of nearshoring for greater sustainability is the shortening of transport routes, which reduces energy and resource consumption. This can be achieved by keeping production sites close to the sales market and the areas where the respective materials are grown. An example of this sourcing strategy is the fashion brand Lanius, for which cotton is sourced in Turkey and directly processed into clothing.[62] Artificial Intelligence is an additional tool to shorten the supply chains. Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality technologies enable consumers to try on clothes virtually. This can help reduce the number of returns and reduce transport emissions. 3D printing technology can also contribute to products, or their components being manufactured closer to the location of the target group.50

3.4 Circular Model

Other ideas aim at the transformation of the current linear business model to a circular one. While the linear model primarily centers around the extraction of materials, textile production, and disposal, the circular model emphasizes the reuse and recycling of materials and garments. The goal is to extend the lifespan of resources and clothing and to reintroduce them into the production cycle at the end of their lifecycle. This can reduce waste, demand for virgin fibers, energy consumption, and environmental impact.46

The process of resource reuse includes recovering water, heat, and carbon dioxide, as well as processing residual materials such as leather scraps, cotton, waste, wool scraps, and reused fabrics. Clothing reuse allows multiple consumers to access them, potentially reducing water usage and waste production by 5-10%.60

Businesses specializing in clothing rental (e.g., Rent the Runway), clothing libraries, and second-hand platforms (e.g., Depop, ThredUp, and Poshmark)45 facilitate maximal garment utilization and higher use intensities. However, the sustainability outcomes of these practices remain uncertain due to a gap between theoretical claims and empirical evidence of practical implementation. The effectiveness of these practices is determined by the extent to which they can replace traditional consumption and production.[63]

Various organizations, including I:CO, Isla Urbana, Triarchy Atelier, Goodwill, Brides for a Cause, Reformation, Fabscrap, TRMTAB, and Patagonia, are involved in redesign initiatives that add value to discarded or used products by transforming them into new clothing items. The redesign process is time-consuming and is complicated by variations in collected textiles, sizes, patterns, fabrics, and colors.28

Textile recycling involves the reprocessing of fibrous material and clothing waste. Mechanical recycling disassembles garments and cuts them into smaller pieces, while chemical recycling decomposes synthetic materials for repolymerization.60These recycling processes can be supported by technologies like spectroscopy and Fibersort. For instance, TrinamiX has developed a spectroscopy solution capable of distinguishing more than 15 types and compositions of textiles.40 Fibersort technology utilizes near-infrared and RGB cameras to sort textiles based on their fiber composition and color properties.50 Prototype chemical recycling technologies can transform mixed fibers back into usable fiber.60 Nonetheless, challenges such as inaccurate sorting, low-quality reuse, variations in textile collections, and their recyclability must be addressed. In some cases, recycling may incur higher costs due to the presence of hazardous chemicals or heavy metals content.46

3.5 Information Transparency, Certificates, and Labels

Product seals are used to identify the final product in compliance with predefined standards. There are many different seals in the textile industry, which refer to different aspects of the product life cycle.51 Several examples and their criteria are shown in Table 2. The environmental and social seals can guide consumers when making purchasing decisions51 by providing relevant information from the corresponding certificates.[64] However, the eco-information can only successfully contribute to the purchase decision if the information is perceived, understood, and considered credible by consumers.[65] Due to their positive impact on the customer’s purchasing decision, green seals are also referred to as a growth-enhancing sustainability strategy, as they make the sustainability performance transparent.[66] Eco-labels are a voluntary consumer-centred mechanism that can promote sustainable consumption.[67] The labels encourage consumers to think about social and environmental issues and to buy in accordance to their personal values.[68] The use of third-party verified sustainability labels can increase consumer confidence in the environmental information of the labeled products.[69] Eco-labels offer companies the opportunity to differentiate their own products from the competition and thus achieve a better image and market position.[70] Eco-labels can help to encourage companies to make their production more sustainable in order to meet their requirements.[71] As labels draw attention to sustainable behavior, non-sustainable competitors in the market are indirectly encouraged to improve their practices.71 In addition, the seals can help the company maintain its commitment to sustainability throughout the supply chain68 and strengthen the uniformity of the sustainability landscape in the industry with their independently verified standards.68 However, the consumer commitment forged by eco-labels can also serve as a counterargument since it requires consumers to learn about the requirements, actors, and verification process of the respective textile label.51 Even reliable information can be difficult to understand and may hinder the conversion of awareness into action.[72] Various initiatives such as “good on you” have already developed a rating system to make the seals comparable but they are not widely known.[73] The existing seals usually only address a certain thematic area of sustainability issues and certain stages of the manufacturing process.69 The concern exists that eco-labels are used for greenwashing. Some brands advertise with self-generated seals that are not verified by third parties.72 Together with unambitious seals, these damage the image of “good” seals, so that consumers can be deterred from buying textiles with seals altogether, even though sustainability is important to them.51 Sustainability audits by third parties increasingly harbour the risk of corruption on the part of the auditors.72 Another disadvantage of seals is that the process of obtaining a seal for companies is associated with high workloads and costs. Therefore, small companies with sustainable products often cannot afford to apply for seals and are thus denied access to interested consumer segments.69

| Label | Criteria |

| Sustainable Fibers Certifications53 | |

| GOTS | Requires at least 70% natural fibers of controlled organic origin; regulates and certifies the entire textile value chain from cultivation to the finished product; prohibits all eleven detox chemical groups in textile production according to social criteria of the International Labour Organisation (ILO)74 |

| OEKO-TEX | “…certifying safe and clean textiles”;25 “monitors textile chemicals that are harmful to health…”;25 “…monitors textile chemicals that are harmful to health…”;69 “Arsenic, lead, phthalates, formaldehyde, pesticides are tested for certification and also the pH level that is acceptable for human skin. Testing products against 350 toxic chemicals present in the product from yarn to the end products”53 |

| Global Recycling Standard (GRS) | “Recycled materials present in the end products is tracked and verified”;53 the seal may be used if a product contains at least 20% recycled materials; the GRS regulates chemical additives74 |

| Environmental Labels53 | |

| bluesign | Comprehensively regulates the chemical risks for the entire production chain; regulates hundreds of chemicals, including all “Detox substance groups”, which are excluded from manufacturing74 |

| B Corp | “Provided for the social and environmental performance of the company”53 |

| Business Standards53 | |

| Fairtrade | “Multistakeholder group based on product-oriented aimed to improve the life of workers and farmers through trade”;53covers the entire supply chain; certified according to compliance with the ILO core labor standards; criteria include living wages (with a transparent transition period of six years), occupational health and safety, safe working conditions, and strengthened labor rights; basic environmental requirements are also included74 |

| Fair Wear | Improve social conditions in sewing factories and ensure living wages[74] |

Table 2: Examples of Ecolabels and their Criteria (own table based on 53,74,25,69)

4 Drivers and Barriers

Fast fashion has a strong negative impact on global warming. Therefore, sustainable fashion is being discussed as an alternative to fast fashion.[75] However, there are potential drivers and barriers regarding an industry focus on sustainable fashion.

4.1 Drivers

4.1.1 Regulatory Pressure & Compliance

To ensure that companies follow the trend of the circular economy, they must be encouraged to do so by new laws and regulations in the absence of voluntary initiative. Regulatory pressure and compliance in particular can be used to tip the scales in this regard.[76]

The disclosure of information through sustainability reports can serve as a motivation to promote sustainable processes in the sector.[77] Not only the negative impact on the ecosystem, but also social aspects such as the poor working conditions of fashion companies are identified and brought to the public’s attention through sustainable reporting.[78]

As a way to counteract the addressed negative influences, new regulations have recently been proposed. In the USA, it is the Fashioning Accountability and Building Real Institutional Change (FABRIC) Act and in Europe, the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR), which includes the Digital Product Passport (DPP).

The Fashioning Accountability and Building Real Institutional Change Act is a proposal presented in 2022 by US Senator Gillibrand to amend the current Fair Labor Standard Act of 1938.[79] Among other things, this amendment is intended to improve working conditions and guarantee fair pay in the fast fashion industry in the USA.[80]

The Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation is a proposal of the EU Commission from the year 2022 and represents an amendment of the previous European Ecodesign Directive. The proposed amendment aims to ensure a high sustainability of products, to motivate the adoption of more sustainable products as well as improving transparency in supply chains. Transparency in this context is to be ensured by the Digital Product Passport. This provides additional data on, for example, the ecological footprint but also the repair options of the respective product.[81]

4.1.2 Increasing Public Awareness

A slightly different circumstance lies in the increase in public awareness regarding the negative environmental impact of the sector. Especially among the younger population customer awareness has risen in recent years. Said generation is putting pressure on the industry as companies are forced to produce more sustainable products if they want to compete in the market in the future.[82]

In response to disasters such as the 2013 Rana Plaza factory collapse in Bangladesh, but also the coverage of negative sustainability practices in general, customers build up pressure to obtain more information regarding the sustainability and ethics of companies and their products. However, it is not only customers who are increasing pressure but also NGOs. Based on the 17 sustainability goals of the UN some companies in the fashion industry felt pressured to adopt sustainability goals to secure their future.[83]

4.1.3 Consumer Demand

Another driver related to public awareness is the increasing consumer demand for social and environmental responsibility products.[84] With an expected market share of 6% by 2026, sustainable fashion is still considered a niche market, but its share is rising steadily.[85] This is primarily attributable to the younger generations who account for the majority of sales with a market share of over 60%[86]

There are several reasons for the increasing consumer demand. Sustainable fashion is considered to be of higher quality than fast fashion, which is why the products tend to last longer. Customers therefore get more value for their money and are rather motivated to buy them because of the long-term savings potential.[87] The fact that sustainable products are less common can create a feeling of exclusivity among customers, which is why customers who want to differentiate themselves from the masses are more likely to buy sustainable products.[88] This is also reflected in the willingness of customers to spend up to 20% more on sustainable fashion if it protects the environment.[89] Owning and wearing sustainable fashion can also trigger a sense of pride through the positive feeling associated with buying the product.87

4.1.4 Profitability of Sustainable Practices

In response to the growing consumer demand for sustainable practices within the fashion industry, the global ethical fashion market is expected to increase by approximately three billion USD between 2021 and 2025. It has been projected that by 2025, it will be worth around 10 billion USD.[90] This trend presents an opportunity for alternative fashion business models, such as circular fashion as discussed in Chapter 3.4, to thrive.60 This section delves into how the adoption of sustainable practices can potentially enhance the profitability of fashion companies.

Service-based business models capitalize on providing services related to clothing items rather than traditional garment sales. By avoiding production and reducing inventory, these models can lower their operational costs. With a value-driven approach that prioritizes the delivery of high-quality services and products, such businesses can command higher prices and consequently increase their profit margins.60

Furthermore, embracing sustainability measures can yield additional economic benefits, particularly in terms of resource preservation achieved through efficiency, sufficiency, or consistency. Savings in energy consumption, water usage, and packaging materials, coupled with opportunities to sell surplus energy, can generate extra revenue or lead to cost reduction.60 For example, an 80% efficiency improvement in wet processing technology could result in savings of 500 USD for every avoided ton of carbon dioxide.[91]

Companies that take strides in adopting sustainable practices early on can gain competitive advantages within the fashion industry.60 These companies can position themselves as sustainability innovators and mitigate risks related to unsustainable behavior.

4.1.5 Brand Image and Corporate Values

Another internal factor of companies that leads to more sustainability is non-economic values.[92] Among the broad measures of principles that motivate sustainable change are social responsibility25 and equality[93], human rights[94], the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs),23 awareness of their environmental impact,[95] and animal rights.94 Values get integrated into a company to address social and environmental inequalities.[96] If the goal of the company is to contribute to achieving the vision of the 2030 Agenda, it can address SDG 1: “no poverty”, SDG 8: “Decent work and economic growth”, and SDG 5: “gender equality” in particular as guidelines for its sustainable development.23, 96An example of a fashion brand that advocates for animal rights is Stella McCartney (2022), which calls itself a “vegetarian company” and states that it stands for “vegan and cruelty-free principles”.23 Regarding the social dimension, some comply with “fair trade” principles in order to contribute to better living conditions for their workers.96 Some fashion brands also refer to themselves as “ethical” and pursue the values of “respect for the people and their community in their supply chain; and respect for the planet with its finite resources”.[97] Corporate values are strongly influenced by the culture of the founder. It takes their personal convictions and vision for the ethical issues to activate the change necessary and make a company truly sustainable.92 Studies also show that companies benefit from setting green values as a hiring criterion for new employees. This is because employees with these values already have the skills and appropriate behavior for environmental innovation.[98] Environmental values also have a positive effect on employee loyalty in companies. The values can be communicated to suppliers and influence the selection process of suppliers. For example, sustainable fashion label Patagonia selects its partnerships with factories according to shared value philosophies.[99] Finally, the company’s sustainability values can be directly incorporated into the company strategy,[100] leading it to adopt a certain organizational and/or management structure93 or business model.25 Overall fashion companies that follow sustainable values and principles are more proactive and ultimately more conducive to sustainable innovation because they attract and retain the appropriate human capital.60

4.2 Barriers

4.2.1 Lack of Regulatory Support, Universal Standards, and Certificates

Another barrier may exist from the government side due to the lack of governance frameworks and sound legislation in many areas.[101] Suppliers are only obliged to comply with national law as there are no internationally binding laws. This has the consequence that the rights that apply to the companies do not have to apply to their manufacturers. That is why violations of the rights cannot be prosecuted under civil and/or criminal law because completely different legal systems exist in these countries.93 Stricter laws that would make fashion companies more accountable (e.g., in liability issues for risks)51 fail because of national interests in not weakening the companies in international competition through the costs incurred.51 In order to increase textile recycling rates both national governments and global policymakers need national and international policy regulations to standardize global textile waste management.44 Also, in the field of information transparency for environmental impacts, there is not yet a sufficient framework to counter unsustainable practices. So far, there are no legal guidelines on the disclosure of non-financial information on human rights risks. The supply chain of companies in high-risk sectors for human rights violations, such as the garment industry, is not subject to mandatory disclosure. In the EU textile regulation, for example, there are regulations on the labelling of textile products but only on material type and washing instructions. Textile recycling is currently still hampered by legal barriers. For example, there is no ban on incineration or landfilling of unsold new goods.34 Lack of environmental and regulatory pressure in the countries of production means that there are no cost incentives for companies in these countries to use renewable energy instead of fossil energy and to act in a more resource-efficient way.34 There is a lack of emission reduction targets, including life cycle GHG emissions for the textile sector.32 The sustainable fashion brand recolution goes beyond legal standards regarding its transparency and disclosures. The company freely discloses data on production countries, the names of suppliers, the number of employees, and the length of collaboration on its website[102]

4.2.2 Societal Awareness, Perception, and Demand

Another obstacle to sustainable fashion is the difficulty of cultivating broad consumer demand due to limited consumer awareness and negative perceptions towards sustainable clothing. Notably, a significant percentage of consumers across generations are willing to spend more money on sustainable products (see Figure 3). However, despite these positive inclinations towards sustainability, a gap between these attitudes and actual behavioral intentions is evident. [103]

Figure 3: Generation Shares Willing to Increase their Budget for Sustainable Products for at least 10% (own illustration according to [104])

The demand for rapid clothing consumption persists.60 For instance, the average consumer in the US purchases a new garment every 5.5 days, while clothing acquisitions in Europe have increased by 40% from 1996 to 2012. Globally, the annual clothing consumption is estimated to be 62 million tonnes, with a projected increase to 102 million tonnes by 2030. Remarkably, the average duration of garment usage has diminished by 36% since 2005,31 currently averaging three years.46 Furthermore, a preference for new clothing over repairing60 or purchasing104 used garments prevails. The perception that sustainable fashion is synonymous with high prices and a lack of trendiness often overshadows sustainability considerations among consumers.60 Rental and second-hand platforms like Rent the Runway or ThredUp address consumer needs for short use times of fashionable garments at lower prices.[105] Moreover, there is a lack of awareness and knowledge surrounding the impacts of fast fashion consumption and the availability of sustainable alternatives.60 Patagonia is known for its educational initiatives and transparency in terms of sustainability, for example, their 2011 campaign “DON’T BUY THIS JACKET”, which advocates for sufficiency, resulting in increased customer awareness.[106]

Negative perceptions related to second-hand and recycled clothing are often rooted in concerns about quality and hygiene.60, 104 A challenge for established fashion enterprises is to undertake rebranding efforts due to a lack of trust in promoted sustainability changes.60

4.2.3 Complex Supply Chains

A major challenge for sustainability in the fashion industry is the complex supply chains, often involving nested structures across multiple industries and countries. Multiple sectors are covered by the supply chains, such as agriculture for natural fibers, petrochemicals for synthetic fibers, garment manufacturing, logistics, and retail. Globalization has made it easier for fashion brands to move their production to countries in the Global South with lower labor costs and more relaxed environmental regulations. This frequently results in the fragmentation of production processes across different countries.31For instance, fast-fashion giant H&M collaborates with approximately 800 suppliers in countries like Vietnam and Bangladesh.91 Such a dispersed supply chain setup makes it challenging to trace and identify all stakeholders and suppliers involved in the garment production process.60 In contrast, the fashion brand Reformation offers a commendable model by running a 70% in-house manufacturing facility, allowing for more direct control over certain production processes.99

Transparency and accountability for business practices in the supply chain suffer under the limited visibility into suppliers. Therefore, making impact evaluation and measuring progress toward sustainability goals and compliance difficult. The lack of information exchange creates uncertainty about the origins and processing of materials, their safe usage, and disposal,31 as well as laborer working conditions. Patagonia documents all entities within its supply chain and enforces chain-of-custody guidelines for suppliers. The brand also participates in sustainability initiatives such as the Higg Index of Sustainable Apparel Coalition, the Regenerative Organic Alliance, and the Climate Action Corps, enabling industry-wide benchmarking and efforts to improve supply chain sustainability.99

4.2.4 Market Priorities and Financial Viability

As in almost every sector, the fashion sector is primarily concerned with financial aspects. These can represent a barrier when it comes to establishing sustainable business models. Fashion companies prioritize low costs and high profits, as the low price is the main reason for customers’ purchase of fast fashion, which in turn means that fast fashion is financially more profitable for them in comparison with sustainable fashion.[107]

Sustainability labels are associated with high costs for companies. This is because there is no single label that can be applied to all areas, and therefore many labels have to be purchased. If these labels are used, it is likely that the costs will then be passed on to the customers, resulting in higher prices for sustainable fashion products.[108] High costs regarding sustainability initiatives and programs can also hamper sustainability efforts.[109]

Furthermore, the remanufacturing process is costly.[110] This results, among other things, from a low process reliability.75 Another aspect is the poor quality of fast fashion products.[111] Only 1% of these products can be recycled.[112] These points lead to the fact that recycling is often not financially viable for the companies.111 To extend the product life cycle, the Eileen Fisher brand company has been buying back clothes from its customers since 2019. These are then reconditioned and resold. Customers receive a reward of five USD regardless of the condition of the clothing.[113]

4.2.5 Technological Limitations

The remanufacturing process is not only a barrier to sustainable fashion for financial reasons. Technological limitations also play a role. The lack of the necessary technical expertise and knowledge for the recycling and design processes poses problems.75 The fashion industry is currently still heavily dependent on fossil fuels. This applies to the entire supply chain. To change this, H&M is one of a few companies that has set the goal of sourcing 100% of its electricity from renewable energies by 2030.[114] To this end, H&M publishes information on the sources of its energy consumption in the Annual and Sustainability Report. The company has already been able to achieve a 92% share of renewable energy in 2022.[115]

In addition, the disassemblement process is highly complex. A large number of textiles are made of several materials, which makes the recycling process much more difficult.15 The company Resortecs provides a possible solution. They offer heat-dissolving threads to simplify the disassembly process. The startup was already able to enter a partnership with the textile company Inditex in 2022.[116] Smart clothing products can be difficult to process because of the various electronic components and the fact that they cannot be washed.[117] The current low-quality results of post-consumer recycling also represent a strong technical limitation.[118]

References

[1] Daniels, A. H. Fashion Merchandising. Harvard Business Review 29, 51- 60 (1951).

[2] Wani, N. S. Factors influencing price perception for fashion: Study of millennials in India. Vision 26, 300-313 (2022).

[3] Millan, E. & Mittal, B. Consumer preference for status symbolism of clothing: The case of the Czech Republic. Psychology & Marketing 34, 309–322 (2017).

[4] Aldrich, W. History of sizing systems and ready-to-wear garments. in Sizing in clothing: Developing effective sizing systems for ready-to-wear clothing (eds. Ashdown, S. P.) 1-56 (CRC Press, 2007).

[5] Hilger, J. The apparel industry in West Europe. CBS. Working Paper No. 22. (2008).

[6] Global Fashion Agenda. Pulse of the Fashion Industry 2017. (2017).

[7] McKinsey & Company. The State of Fashion 2017. (2017).

[8] Clube, R. K. M. & Tennant, M. Social inclusion and the circular economy: The case of a fashion textiles manufacturer in Vietnam. Business Strategy & Development 5, 4–16 (2022).

[9] The Fashion Industry and Its Key Sectors The Fanss https://thefanss.com/blog/the-fashion-industry-and-its-key-sectors (2022).

[10] Garment Manufacturing process from Fabric to finished products Dony Garment https://garment.dony.vn/garment-manufacturing-process-from-fabric-to-finished-products/ (2022).

[11] Doeringer, P. & Crean, S. Can fast fashion save the apparel industry? Socio-Economic Review 4, 353-377 (2006).

[12] Changing Markets Foundation. Fossil Fashion. (2021).

[13] Charpail, M. What’s wrong with the fashion industry? Sustain Your Style https://www.sustainyourstyle.org/en/whats-wrong-with-the-fashion-industry (2022).

[14] Wackernagel, M. & Rees, W. Our Ecological Footprint: Reducing Human Impact on the Earth. (New Society Publishers, 1962).

[15] Centobelli, P., Abbate, S., Nadeem, S. P. & Garza-Reyes, J.A. Slowing the fast fashion industry: An all-around perspective. Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 38, 100684 (2022).

[16] Karssing, S. Industries with high water consumption Smarter Business https://smarterbusiness.co.uk/blogs/the-top-5-industries-that-consume-the-most-water/ (2020).

[17] Fast Fashion and its Environmental Impact Goodwill of Central Iowa https://www.dmgoodwill.org/sustainability/fast-fashion-environmental-impact/ (2023).

[18] Chemitei, J. & Modester, L. SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy, and the Fashion Industry Threading Change https://www.threadingchange.org/blog/sdg-7 (2022).

[19] Shou, M. & Domenech, T. Integrating LCA blockchain technology to promote circular fashion – A case study of leather bags. Journal of Cleaner Production 373, 133557 (2022).

[20] Measuring Fashion’s Ecological Footprint Common Objective https://www.commonobjective.co/article/measuring-fashion-s-ecological-footprint (2021).

[21] WIK. Taming Fashion Part One: Why reducing the use of animals is crucial for a truly sustainable fashion industry. (2023).

[22] Peters, G., Li, M. & Lenzen, M. The need to decelerate fast fashion in a hot climate – A global sustainability perspective on the garment industry. Journal of Cleaner Production; 295, 126390 (2021).

[23] Louw, L. B., van Antwerpen, S. & Esterhuyzen, E. The Garments Economy: An African Perspective. The Garment Economy (eds. Brandstrup. M., Ryding D., Caratù, M., Dana, L.-P., Vignali, G. 31-50 (Springer International Publishing; Imprint Springer, 2023).

[24] International Labour Office, Sectoral Policies. The future of work in textiles, clothing, leather and footwear. Working Paper (2019).

[25] Matthes, A. Sustainable Textile and Fashion Value Chains (Springer International Publishing AG, 2021).

[26] Ahmed, M. S. & Uddin, S. Workplace Bullying and Intensification of Labour Controls in the Clothing Supply Chain: Post-Rana Plaza Disaster, 539–556 (2022).

[27] Musiolek, B., Tamindžija, B., Aleksić, S., Oksiutovych, A. & Dutchak, O. Exploitation Made in Europe (2020).

[28] Sustainability in the Textile and Apparel Industries (Springer International Publishing, 2020).

[29] Hammer, N. & Plugor, R. Disconnecting Labour? The Labour Process in the UK Fast Fashion Value Chain (2019).

[30] Alamgir, F. & Banerjee, S. B. Contested compliance regimes in global production networks: Insights from the Bangladesh garment industry. Human Relations; 72, 272–297 (2019).

[31] Niinimäki, K. et al. The Environmental Price of Fast Fashion. Nat Rev Earth Environ; 1, 189–200 (2020).

[32] Clean Clothes Campaign. The intersections of environmental and social impacts of the garment industry. (2022).

[33] International Labour Organization. Moving the needle: Gender equality and decent work in Asia’s garment sector Regional Road Map. For Consultation, 1–44 (2021).

[34] Ellen MacArthur Foundation. A new Textile economy. Redesigning fashion’s future. (2017).

[35] Ribul, M. et al. Mechanical, chemical, biological: Moving towards closed-loop bio-based recycling in a circular economy of sustainable textiles. Journal of Cleaner Production 326, 129325 (2021).

[36] McKinsey & Company and GFA. Fashion on Climate: How the Fashion Industry Can Urgently Act to Reduce its Greenhouse Gas Emissions. (2020).

[37] EPRS. Environmental Impact of the textile and clothing industry: What consumers need to know. (2019).

[38] European Topic Centre Waste and Materials in a Green Economy. Plastic in Textiles: Potentials for Circularity and Reduced Environmental and Climate Impacts. (2021).

[39] Sustainable Technologies for Fashion and Textiles (Woodhead Publishing, 2020).

[40] Konina, N. Y. Smart Digital Innovations in the Global Fashion Industry and a Climate Change Action Plan. in Smart Green Innovations in Industry 4.0 for Climate Change Risk Management (eds. Popkova, E. G.) 255-263 (Springer Nature Switzerland, 2023).

[41] Berradi, M. et al. Textile Finishing Dyes and Their Impact on Aquatic Environs. Heliyon 5, e02770 (2019).

[42] Islam, T., Repon, Md. R., Islam, T., Sarwar, Z. & Rahman, M. M. Impact of Textile Dyes on Health and Ecosystem: A Review of Structure, Causes, and Potential Solutions. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 30, 9207-9242 (2023).

[43] European Parliament. The impact of textile production and waste on the environment. (2023).

[44] Hole, G. & Hole, A. S. Recycling as the way to greener production: A mini review. Journal of Cleaner Production; 212, 910–915 (2019).

[45] Dolzhenko, I. B. & Churakova, A. A. Industry 4.0 Innovations in the Global Fashion Sector and Their Role in Contributing to Minimizing Its Negative Impact on the Climate. in Current Problems of the Global Environmental Economy Under the Conditions of Climate Change and the Perspectives of Sustainable Development. (eds. Popkova, E. G., Sergi, B. S.) 107-116 (Springer Nature Switzerland, 2023).

[46] Shirvanimoghaddam, K., Motamed, B., Ramakrishna, S. & Naebe, M. Death by waste: Fashion and textile circular economy case. Sci Total Environ; 718, 137317 (2020).

[47] Geyer R. Distribution of plastic waste generation worldwide in 2018, by sector [Graph]. In Statista. Retrieved August 29, 2023, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1166582/global-plastic-waste-generation-by-sector/. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1166582/global-plastic-waste-generation-by-sector/ (2020).

[48] Mishra, P. K., Izrayeel, A. M. D., Mahur, B. K., Ahuja, A. & Rastogi, V. K. A comprehensive review on textile waste valorization techniques and their applications; 29, 65962–65977 (2022).

[49] Manshoven, S., Smeets, A., Arnold, M. & Mortensen, L. F. Plastic in Textiles: Potentials for Circularity and Reduced Environmental and Climate Impacts (2021).

[50] Daukantienė, V. Analysis of the Sustainability Aspects of Fashion: A Literature Review. Textile Research Journal; 93, 991–1002 (2023).

[51] CSR und Fashion (Springer Gabler, 2018).

[52] Liu, Y., et al. Could the recycled yarns substitute for the virgin cotton yarns: a comparative LCA. Int J Life Cycle Assess; 25, 2050–2062 (2020).

[53] Novel Sustainable Alternative Approaches for the Textiles and Fashion Industry (Springer Nature Switzerland; Imprint Springer, 2023).

[54] Aslan, A. Determination of heavy metal toxicity of finished leather solid waste. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol; 82, 633–638 (2009).

[55] Wjunow, C., Moselewski, K.-L., Huhnen, Z., Selina, S. & Lilia, S. Sustainable Textiles from Unconventional Biomaterials—Cactus Based. engineering proceedings, 58 (2023).

[56] Diwan, P. & Baliyan, R. Vegan Fashion or Sustainable Apparels: India’s next move post pandemic. The Empirical Economics Letters, 136–146 (2021).

[57] El Shishtawy, N., Sinha, P. & Bennell, J. A. A Comparative Review of Zero-Waste Fashion Design Thinking and Operational Research on Cutting and Packing Optimization. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education 15, 187-199 (2022).

[58] Da Giau, A., Foss, N. J., Furlan, A. & Vinelli, A. Sustainable development and dynamic capabilities in the fashion industry: A multi‐case study. Coporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 1509–1520 (2019).

[59] Butollo, F. & Staritz, C. Deglobalization, Reconfiguration, or Business as Usual? (Weizenbaum Institute for the Networked Society – The German Internet Institute, 2022).

[60] De Aguiar Hugo, A. , de Nadae, J. & da Silva Lima, R. Can Fashion Be Circular? A Literature Review on Circular Economy Barriers, Drivers, and Practices in the Fashion Industry’s Productive Chain. Sustainability; 13, 12246 (2021).

[61] Givn Berlin. Fair Trade Kleidung aus nachhaltigen Materialien. https://givnberlin.com/pages/unsere-produktion (2023).

[62] LANIUS. Unsere Maßnahmen zur CO2 Reduktion, 03/ Kurze Wertschöfpungsketten. https://www.lanius.com/de/nachhaltigkeit/co2-ausgleich/ (2023).

[63] Johnson, E. & Plepys, A. Product-Service Systems and Sustainability: Analyzing the Environmental Impacts of Rental Clothing. Sustainability 13, 2118 (2021).

[64] Sustainable Approaches in Textiles and Fashion (Springer Singapore; Imprint Springer, 2022).

[65] Kushwaha, G. S. & Sharma, N. K. Eco-labels: A tool for green marketing or just a blind mirror for consumers. Electronic Green Journal (2019).

[66] Eide, A. E., Saether, E. A. & Aspelund, A. An investigation of leaders’ motivation, intellectual leadership, and sustainability strategy in relation to Norwegian manufacturers’ performance. Journal of Cleaner Production; 254, 120053 (2020).

[67] Barkemeyer, R., Young, C. W., Chintakayala, P. K. & Owen, A. Eco-labels, conspicuous conservation and moral licensing: An indirect behavioural rebound effect. Ecological Economics; 204, 107649 (2023).

[68] Smyth, C. & Zambrelli, F. Scaling ESG Solutions in Fashion 2023, 1–70 (2023).

[69] Turunen, L. L. M. & Halme, M. Communicating actionable sustainability information to consumers: The Shades of Green instrument for fashion. Journal of Cleaner Production; 297, 126605 (2021).

[70] Oelze, N., Gruchmann, T. & Brandenburg, M. Motivating Factors for Implementing Apparel Certification Schemes—A Sustainable Supply Chain Management Perspective. Sustainability; 1 (2020).

[71] Progress on Life Cycle Assessment in Textiles and Clothing (Springer Nature Singapore; Imprint Springer, 2023).

[72] Sahimaa, O. et al. The only way to fix fast fashion is to end it. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 137–138 (2023).

[73] Mukendi, A., Davies, I., Glozer, S. & McDonagh, P. Sustainable fashion: current and future research directions. Sustainable fashion, 2873–2909 (2019).

[74] Brodde, K. Textil-Siegel im Greenpeace-Check | Greenpeace. Textil Siegel im Greanpeace-Check (2018).

[75] Pal, R., Samie, Y. & Chizaryfard, A. Demystifying process-level scalability challenges in fashion remanufacturing. An interdependence perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production 286, 125498 (2021).

[76] Campbell, J. L. Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review 32, 946-967 (2007).

[77] Albareda, L., Lozano, J. M. & Ysa, T. Public policies on corporate social responsibility. The role of governments in Europe. Journal of Business Ethics 74, 391-407 (2007).

[78] Pederson, E. R. G. & Gwozdz, W. From resistance to opportunity-seeking: Strategic responses to institutional pressures for corporate social responsibility in the Nordic fashion industry. Journal of Business Ethics 119, 245-264 (2014).

[79] Congress.gov. S. 4213. (2022).

[80] Take Action to Repair Fashion The FABRIC Act https://thefabricact.org/ (n.d.).

[81] European Environmental Bureau. New EU eco-design proposals. (2022).

[82] Gazzola, P., Pavione, E., Pezzetti, R. & Grechi, D. Trends in the fashion industry. The perception of sustainability and circular economy: A gender/generation quantitative approach. Sustainability 12, 2809 (2020).

[83] Ertekin, Z. O. & Atik, D. Institutional constituents of change for a sustainable fashion system. Journal of Macromarketing 40, 362-379 (2020).

[84] Bläse, R., Filser, M., Kraus, S., Puumalainen, K. & Moog, P. Non-sustainable buying behavior: How the fear of missing out drives purchase intentions in the fast fashion industry. Business Strategy and the Environment, 1-16 (2023).

[85] Statista Research Department. Revenue share of the sustainable apparel market worldwide from 2013 to 2026 Statista https://www.statista.com/forecasts/1307848/worldwide-sales-of-sustainable-clothing-items (2023).

[86] Smith, P. Estimated market share of sustainable apparel in the United States in 2022, by generation Statista https://www.statista.com/statistics/1276260/market-share-of-sustainable-apparel-in-the-us-by-generation/ (2023)

[87] Lundblad, L. & Davies, I. A. The values and motivations behind sustainable fashion consumption. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 15, 149-162 (2016).

[88] Şener, T., Bişkin, F. & KıIınç, N. Sustainable dressing: Conmsumer’s value perceptions towards slow fashion. Business Strategy and the Environment 28, 1548-1557 (2019).

[89] Soyer, M. & Dittrich, K. Sustainable consumer behavior in purchasing, using and disposing of clothes. Sustainability 13, 8333 (2021).

[90] Statista. Estimated Value of the Ethical Fashion Market Worldwide from 2022 to 2027 Statista https://www.statista.com/statistics/1305641/ethical-fashion-market-value/ (2023).

[91] Wren, B. Sustainable Supply Chain Management in the Fast Fashion Industry: A Comparative Study of Current Efforts and Best Practices to Address the Climate Crisis. Cleaner Logistics and Supply Chain 4, 100032 (2022).

[92] Dicuonzo, G., Galeone, G., Ranaldo, S. & Turco, M. The Key Drivers of Born-Sustainable Businesses: Evidence from the Italian Fashion Industry. Sustainability, 1–16 (2020).

[93] Cerchia, R. E. & Piccolo, K. The Ethical Consumer and Codes of Ethics in the Fashion Industry. Laws, 1–19 (2019).

[94] Heinze, L. Fashion with heart: Sustainable fashion entrepreneurs, emotional labour and implications for a sustainable fashion system. Sustainable Development, 1554–1563 (2020).

[95] Kiran, A. s. Greening textile industry reduces environmental pollution- A research on eco-friendly garments. Interdisciplinary Science, 175–180 (2021).

[96] Argade, P., Salignac, F. & Barkemeyer, R. Opportunity identification for sustainable entrepreneurship: Exploring the interplay of individual and context level factors in India. Business Strategy and the Environment, 3528–3551 (2021).

[97] Miotto, G. & Youn, S. The impact of fast fashion retailers’ sustainable collections on corporate legitimacy: Examining the mediating role of altruistic attributions. Journal of Consumer Behavior, 618–631 (2020).

[98] Tran, T. D., Huan, D. M., Phan, T. T. H. & Do, H. L. The impact of green intellectual capital on green innovation in Vietnamese textile and garment enterprises: mediate role of environmental knowledge and moderating impact of green social behavior and learning outcomes. Environmental science and pollution research international, Springer 30, 74952–74965 (2023).

[99] Soni, S. & Baldawa, S. Analyzing Sustainable Practices in Fashion Supply Chain. International Research Journal of Business Studies; 16, 11–25 (2023).

[100] Afsar, B., et al. Promoting employee’s proenvironmental behavior through green human resource management practices, 424–438 (2019).

[101] Payne, A. & Mellick, Z. Tackling Overproduction? The Limits of Multistakeholder Initiatives in Fashion. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy; 11 (2), 30–46 (2022).

[102] recolution GmbH & Co.KG. Amaral. https://www.recolution.de/pages/produzent-amaral (2023).

[103] Blazquez, M., Henninger, C. E., Alexander, B. & Franquesa, C. Consumers’ Knowledge and Intentions towards Sustainability: A Spanish Fashion Perspective. Fashion Practice 12, 34-54 (2020).

[104] Kim, I., Jung, H. J. & Lee, Y. Consumers’ Value and Risk Perceptions of Circular Fashion: Comparison between Secondhand, Upcycled, and Recycled Clothing. Sustainability 13, 1208 (2021).

[105] Shrivastava, A., Jain, G., Kamble, S. S. & Belhadi, A. Sustainability through Online Renting Clothing: Circular Fashion Fueled by Instagram Micro-Celebrities. Journal of Cleaner Production 278, 123772 (2021).

[106] Schatz, C. & Pfoertsch, W. Case Study: Patagonia – A Human-Centered Approach to Marketing. in H2H Marketing (eds. Kotler, P., Pfoertsch, W., Sponholz, U. & Haas, M.) 195-213 (Springer Cham, 2023).

[107] Hageman, E., Kumar, V., Duong, L., Kumari, A. & McAuliffe, E. Do fast fashion sustainable business strategies influence attitude, awareness and behaviours of female consumers? Business Strategy and the Environment, (2023).

[108] Henniger, C. Traceability the new Eco-label in the slow-fashion industry – Consumer perceptions and micro-organisations responses. Sustainability 7, 6011-6032 (2015).

[109] Da Giau, A. et al. Sustainability practices and web-based communication: An analysis of the Italian fashion industry. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 20, 72-88 (2016).

[110] Rissanen, T. Brands are leaning on „recycled“ clothes to meet sustainability goals. How are they made? And why is recycling them so hard? The Conversation http://theconversation.com/brands-are-leaning-on-recycled-clothes-to-meet-sustainability-goals-how-are-they-made-and-why-is-recycling-them-further-so-hard-184406 (2022).

[111] Dissayanake, D. G. K. & Sinha, P. Sustainable Waste Management Strategies in the Fashion Industry Sector. International Journal of Environmental, Cultural, Economic and Social Responsibility 8, 77-90 (2012).

[112] Ruiz, A. Textile Waste Statistics TheRoundup.org https://theroundup.org/textile-waste-statistics/ (2023).

[113] Herndon, K. The Pain of Progress: Our Renew Program Reaches 2 Million Garments Eileen Fisher https://www.eileenfisher.com/circular-by-design/journal/sustainability/renew-program-reaches-2-million-garments.html?loc=US (2023).

[114] Stand.earth. Fossil-Free Fashion Scorecard 2023. (2023).

[115] H&M Group. Annual and Sustainability Report 2022. (2022).

[116] Serafin, A. Resortecs makes clothes recycling easier with dissolvable thread European Investment Bank https://www.eib.org/en/stories/recycling-clothes-resortecs (2023).

[117] Jiang, S., Stange, O., Bätcke, F. O., Sultanova, S. & Sabantina, L. Applications of Smart Clothing – Brief Overview. Communications in Development and Assembling of Textile Products 2, 123-140 (2021).

[118] Colucci, M. & Vecchi, A. Close the loop: Evidence on the implementation of the circular economy from the Italian fashion industry. Business Strategy and the Environment 30, 856-873 (2021).