1 Definition and goals

Sustainable finance and investment play an important role in today’s financial sector, as more and more investors want to put their money into socially and environmentally responsible businesses 1 Drost, F. M. (2021). Nachhaltiges Investment – Vor allem Privatanleger treiben den Trend zu nachhaltigen Geldanlagen an. In: Handelsblatt. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://www.handelsblatt.com/finanzen/anlagestrategie/trends/nachhaltiges-investment-vor-allem-privatanleger-treiben-den-trend-zu-nachhaltigen-geldanlagen-an/27262674.html?ticket=ST-1240903-zJ4Py6RRecaTPsJUH7Nl-ap6 . Through its investment strategies and lending policies, the financial sector has a special importance and power with regard to society and other industries. A significant factor for the financial sector is sustainability, as demonstrated by sustainable finance and investment 2 Frese, M., & Colsman, B. (2018). Nachhaltigkeitsreporting für Finanzdienstleister. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer . Sustainable finance means that environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors are relevant and play a part in investment decision making in the financial sector, usually implying a more long-term perspective 3 European Commission (2021). Overview of sustainable finance. Retrieved 24/08/2021: https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/banking-and-finance/sustainable-finance/overview-sustainable-finance_en . In addition, sustainable investment was defined by Germany’s finance minister, Scholz (2021), as “investing money with a view to the future and thereby supporting structural change” 4 Scholz, O. (2021). In: Federal Ministry of Finance. Setting the course for the financial sector: climate action and sustainability as core themes. Retrieved 24/08/2021: https://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/EN/Pressemitteilungen/2021/2021-05-05-sustainable-finance-strategy.html . So, sustainability for the financial sector means acting in an ecologically, socially, and societally responsible manner and, at the same time, being economically successful from a long-term perspective 2 Frese, M., & Colsman, B. (2018). Nachhaltigkeitsreporting für Finanzdienstleister. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer .

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals of the Agenda 2030, developed by the United Nations (UN), cover social, economic, political, and institutional, as well as environmental, aspects of development. They serve as an ideal orientation benchmark for investments with the broadest possible positive impact 5 United Nations (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for sustainable development A/RES/70/1. Retrieved: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf . They target all levels of society, ranging from the governance of communities to that of the private economy 6 Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung (2021). Agenda 2030 – Ziele für eine nachhaltige Entwicklung weltweit. Retrieved 25/08/2021: https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/themen/nachhaltigkeitspolitik/ziele-fuer-eine-nachhaltige-entwicklung-weltweit-355966 . Therefore, the financial sector has a significant role to play in the implementation of the 17 goals, for example, through the provision of public goods and services 5 United Nations (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for sustainable development A/RES/70/1. Retrieved: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf .

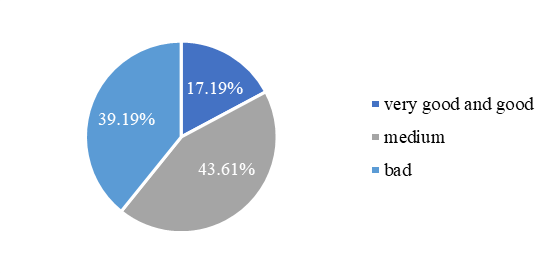

In the long term, the idea of sustainability, especially when faced with climate change, is becoming more and more prevalent in companies. The Oekom Corporate Responsibility Review (2018) shows that the average performance rating of companies in terms of sustainability has increased in industrialized countries by 4.19 points, up to 31.50 from a possible 100 points, between the years 2013 to 2017. In emerging markets, there was an even larger increase from 14.78 points in 2013 to 21.73 points in 2017. Moreover, this rating of companies’ sustainability performance is the one with the most positive result since the review started to be published annually.

2 Measures

“Sustainable investment refers to the integration of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors in investment decision-making” 8 GSIA (2021). Global Sustainable Investment Review 2020. Retrieved on 28/08/2021: http://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/GSIR-2020.pdf. The definition of sustainable investment includes the consideration of ESG factors. Furthermore, the use of ESG factors is very globally significant in the field of sustainable investment 8 GSIA (2021). Global Sustainable Investment Review 2020. Retrieved on 28/08/2021: http://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/GSIR-2020.pdf . For this reason, it is essential for sustainable investment to be able to measure and assess investment decisions according to these factors. In order to base investment decisions on a broad database and comparable, unambiguous key figures, investors refer to ESG ratings 9 Berg, F., Koelbel, J. F., & Rigobon, R. (2020). Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. The Divergence of ESG Ratings. MIT Sloan School Working Paper, 1-63. . “ESG ratings are indices that aggregate a varying number of indicators into a score that is designed to measure a firm’s ESG performance. Conceptually, such a rating can be described in terms of scope, measurement, and weights” 9 Berg, F., Koelbel, J. F., & Rigobon, R. (2020). Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. The Divergence of ESG Ratings. MIT Sloan School Working Paper, 1-63. .

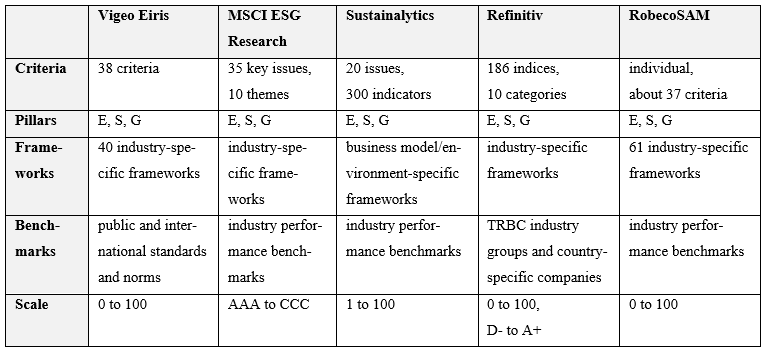

Many different institutions set ESG standards, and various companies collect and provide ESG information and convert it into ESG ratings 10 Doh, J. P., Howton, S. D., Howton, S. W., & Siegel, D. S. (2010). Does the market respond to an endorsement of social responsibility? The role of institutions, information, and legitimacy. Journal of Management, 36(6), 1461-1485. . Globally, there are many organizations whose work is related to the general topic of ESG or even focuses on the ESG performance of companies 11 World Economic Forum (2021). ESG Ecosystem Map. Retrieved on 28/08/2021: https://widgets.weforum.org/esgecosystemmap/index.html#/ . Some of these organizations are for-profit companies, while others are not-for-profit ones. At the same time, some organizations are characterized by thematic focuses, while others deal with all ESG-relevant topics. The service portfolio of these companies ranges from overall assessment results, including the assessment of sub-dimensions, evaluations based on specific topics, and overall rankings of companies based on specific results, to tools for assessing the ESG performance of companies. In addition, some companies also offer consulting services 12 Eccles, R. G., & Stroehle, J. C. (2018). Exploring Social Origins in the Construction of ESG Measures. 1-36. . The World Economic Forum (WEF) has developed an “Ecosystem Map” for organizations that are relevant to sustainable investment and ESG topics. The “Ecosystem Map” is attached in Annex 1. Here, for example, institutions are classified with the goal of standardizing non-financial reporting, such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) 13 Chatterji, A. K., Durand, R., Levine, D., & Touboul, S. (2016). Do ratings of firms converge? Implications for managers, investors and strategy researchers. Strategic Management Journal, 37. 1597-1614. . In addition, the most important vendors of ESG ratings are shown. These include, for example, Vigeo Eiris, MSCI ESG Research, Sustainalytics, Refinitiv, and RobecoSAM 12 Eccles, R. G., & Stroehle, J. C. (2018). Exploring Social Origins in the Construction of ESG Measures. 1-36. . As these companies are responsible for measuring sustainability in the context of finance and investment, their procedures will be presented in terms of content and methodology in order to get an overview of their ESG ratings and how they are composed. Other rating vendors exist, such as ISS-oekom, which are not considered in detail here.

The ESG rating of Vigeo Eiris is based on a total of 38 criteria covering the pillars of E, S, and G. These criteria are processed in 40 different industry-specific frameworks. An overview of the criteria and frameworks of Vigeo Eiris is attached in Annexes 2 and 3. The analysis of Vigeo Eiris shows ESG overall scores, pillar-specific scores for E, S, and G, and individual scores for the criteria. Principles based on generally accepted norms and standards from organizations, such as the UN, International Labor Organization (ILO), and Organization for Economic Cooporation and Development (OECD), serve as benchmarks for the assessment. These include, for example, “The Ten Principles of the Global Compact of the United Nations.” The individual criteria, the pillar-specific ratings, and the ESG overall rating are assigned a value between 0 and 100. In each industry framework, the 38 generic ESG criteria are assessed according to a multi-stage weighting and assessment methodology and extrapolated bottom-up. This includes an industry-specific risk assessment and a company-specific management assessment. Vigeo Eiris uses qualitative and quantitative data and management and performance data as well as self-reported and third-party reported data for its ESG assessments 14 Vigeo Eiris (2020). ESG Assessment Methodology. Retrieved on 28/08/2021: https://vigeo-eiris.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/VE_ESG-Assessment-Summary_2021-2.pdf .

MSCI ESG Research examines a total of 35 ESG key issues divided into 10 themes within the E, S, and G pillars for its ESG rating. Based on this, companies are assessed within a non-predefined industry-specific framework. In Annexes 4 and 5, overviews of the MSCI ESG Research key issues and methodology are attached. MSCI ESG Research’s analysis shows an ESG overall rating and pillar-specific scores for E, S, and G. The benchmarks for the assessment are the standards and performance of the respective industry peers. The final ESG overall rating is a letter rating on a scale from AAA to CCC. The derivation of this rating is based on a stepwise bottom-up extrapolation on a scale of 0 to 10 along an industry-specific weighting and normalization compared to the industry’s ESG ratings. Within the E and S pillars, the exposure and management dimensions are weighed against each other for each key issue in relation to risks and opportunities in order to arrive at an assessment. With regard to the G pillar, an absolute assessment of the key themes is carried out. MSCI ESG Research uses macro data at the segment or geographic level from academic, government, and non-government datasets, corporate disclosures, government databases, media, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and other stakeholder sources on specific companies 15 MSCI ESG Research (2020). MSCI ESG Ratings Methodology. Retrieved on 28/08/2021: https://www.msci.com/documents/1296102/21901542/MSCI+ESG+Ratings+Methodology+-+Exec+Summary+Nov+2020.pdf .

Sustainalytics offers an ESG risk rating, which is a measure of a company’s unmanaged ESG risk. It is composed of three building blocks: corporate governance, material ESG issues (MEIs), and idiosyncratic issues 16 Sustainalytics (2021). ESG Risk Ratings Methodology Abstract. Retrieved on 28/08/2021: https://connect.sustainalytics.com/hubfs/INV/Methodology/Sustainalytics_ESG%20Ratings_Methodology%20Abstract.pdf . The MEIs comprise 20 ESG issues made up of 300 ESG indicators. It is the most important block 17 Sustainalytics (2021). Overview of Sustainalytics’ Material ESG Issues. Retrieved on 28/08/2021: https://connect.sustainalytics.com/hubfs/INV/MEI/Overview-of-Sustainalytics-Material-ESG-_Final_feb2021.pdf. Annexes 6 and 7 provide an overview of the ESG issues of Sustainalytics and the methodology of the ESG risk rating. Relevant ESG issues are selected on a case-by-case basis using typical business models and the business environment. The ESG issues are composed of different indicators from the E, S, and G pillars. Pillar scores are only used to supplement the ESG risk rating. The calculation methodology for the pillar scores is attached in Annex 8. The benchmark for the ESG risk rating is the industry performance. All ratings are on a scale of 1 to 100. The assessment is based on an evaluation of the individual topics using a comparison of the dimensions of risk and management. The ESG risk rating is calculated taking into account the relationship between the industry and the company, as well as risk manageability. The analysis incorporates company data in the form of public announcements, data from the media, daily news, and third-party research, such as NGO reports 16 Sustainalytics (2021). ESG Risk Ratings Methodology Abstract. Retrieved on 28/08/2021: https://connect.sustainalytics.com/hubfs/INV/Methodology/Sustainalytics_ESG%20Ratings_Methodology%20Abstract.pdf .

Refinitiv creates an ESG rating from 186 ESG indices broken down into 10 categories and covering the E, S, and G pillars. Industry-specific frameworks are created by directing the ESG indices accordingly. An overview of the ESG rating methodology and the categories is attached in Annexes 9 and 10. The results of the analysis include an ESG overall rating, pillar-specific scores, and individual scores for the ten categories. Refinitiv uses a points scale from 0 to 100 for the ESG rating, as well as a letter scale from D- to A+. Within the E and S pillars, The Refinitiv Business Classification (TRBC) industry groups are used as benchmarks. For the assessment of the G pillar categories, companies of the country in which the company was founded are used as a benchmark. The rating works using a step-by-step bottom-up extrapolation. A percentage weighting is used to infer the overall rating from the individual categories via the pillars. While the weighting of the G pillar is industry independent, the weighting of the E and S pillars is based on the industry-specific weighting of the associated categories. The basis for Refinitiv’s EGS rating is publicly reported information 18 Refinitiv (2021). Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Scores from Refinitiv. Retrieved on 28/08/2021: https://www.refinitiv.com/content/dam/marketing/en_us/documents/methodology/refinitiv-esg-scores-methodology.pdf .

RobecoSAM’s ESG rating takes into account various criteria covering economic, social, and environmental dimensions and thus the E, S, and G pillars. From this, an ESG overall rating, pillar-specific scores, and individual scores for the criteria are determined as part of the analysis. A total of 61 industries were defined using the Global Industry Classification System (GICS) to create the ESG ratings. Individual assessment frameworks are created for each of these industries based on unique compilations and weightings of ESG criteria. The compilation of criteria consists of generic criteria on the one hand and industry-specific criteria on the other. This compilation is derived from an analysis of industry-specific business value drivers. Annex 11 contains an exemplary compilation of ESG criteria for three industries. The valuation is based on a benchmark developed by RobecoSAM, which is based on the results of previous years and the valuations within an industry. For the assessment, various factors are taken into account, such as the implementation of strategies to manage sustainability risks or the determination of the potential financial impact of the engagement on sustainability factors. The analysis results are provided by RebocoSAM on a scale from 0 to 100. The ESG overall rating is calculated using a step-by-step bottom-up extrapolation. Points are awarded for the individual ESG criteria. The weightings are used to combine the points with the pillar scores and the overall rating. The data for RobecoSAM’s ESG rating come from its own survey based on a questionnaire and supporting documents. This is supplemented by a media and stakeholder analysis. RobecoSAM’s ESG rating is also distinguished by the fact that it forms the basis for the Dow Jones Sustainability Indices (DJSI) 19 RobecoSAM (2021). Measuring Intangibles. Retrieved on 28/08/2021: https://www.spglobal.com/esg/csa/static/docs/measuring_intangibles_csa-methodology.pdf . Table 1 summarizes the findings.

An important finding with regard to the ESG ratings is that the various ratings of the different vendors differ greatly from one another. Depending on the area of application, the indicators measured, the underlying methodology, and the weights used, different measures are generated. This is already clear in view of the rating vendors presented, but this is also the conclusion reached by a wide variety of studies using a wide variety of methods in the evaluation of different cases9 Berg, F., Koelbel, J. F., & Rigobon, R. (2020). Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. The Divergence of ESG Ratings. MIT Sloan School Working Paper, 1-63. 13 Chatterji, A. K., Durand, R., Levine, D., & Touboul, S. (2016). Do ratings of firms converge? Implications for managers, investors and strategy researchers. Strategic Management Journal, 37. 1597-1614. 20 Delmas, M., Etzion, D., & Nairn-Birch, N. (2013). Triangulating Environmental Performance: What Do Corporate Social Responsibility Ratings Really Capture?. Academy of Management Perspectives, 27(3), 255-267. .

As already shown, ESG vendors collect their underlying ESG data at regular intervals in a variety of ways. They use surveys of companies, analyses of corporate documents, and interviews with company employees and other stakeholders. However, increasingly, natural language processing and artificial intelligence technologies are also used to search the web of unstructured data. Some also conduct surveys of individuals to assess perceptions of companies in different areas. The data are used in different ways to create a specific set of indicators that represent qualitative and quantitative data dimensions, frameworks, and conventions. Each vendor has a unique proprietary methodology for processing the data. However, the vendors do not make transparent which precise indicators and methodologies they use. In addition, organizations also exist that use data from these ESG data vendors to create their own rankings and aggregated index solutions. Due to the problem of the low comparability of the ESG ratings of the different vendors, there are also meta-ratings for the evaluation of the individual ESG ratings and initiatives, with the intention of working through the differences between the ESG ratings. These include the Sustainability and ESG Ratings and Rankings Working Group of the World Business Council on Sustainable Development (WBCSD)12 Eccles, R. G., & Stroehle, J. C. (2018). Exploring Social Origins in the Construction of ESG Measures. 1-36. .

However, efforts are also being made to develop a uniform basis on which the comparability of the various ESG ratings is possible and to give a better overview of the various ESG ratings of the vendors, how they are composed, and consequently, how they differ. So-called taxonomies have been developed for this purpose. These include the taxonomy based on the “Aggregate Confusion” research project and another according to the SASB. In developing the taxonomies, the ESG ratings of Vigeo Eiris, MSCI, Sustainalytics, Asset4, RobecoSAM, and KLD were considered. The data used for the analysis are from 2014, which is why the MSCI and KLD rating vendors are considered separately. Refinitiv is listed as Asset4. For the analysis, the ESG ratings were divided into three levels. This includes the scope of all individual attributes that make up the ESG ratings, the indicators used to measure the attributes, and the aggregation rule for weighting and mathematically combining the indicators.9 Berg, F., Koelbel, J. F., & Rigobon, R. (2020). Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. The Divergence of ESG Ratings. MIT Sloan School Working Paper, 1-63.

By categorizing and classifying the individual indicators of the ESG rating vendors in taxonomies, it is possible to check and compare the extent to which the different rating vendors take the individual categories into account. These are approximate values, as the transparency of the units of the individual indicators of the rating vendors is very limited.9 Berg, F., Koelbel, J. F., & Rigobon, R. (2020). Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. The Divergence of ESG Ratings. MIT Sloan School Working Paper, 1-63.

Overall, the ESG ratings of Vigeo Eiris, MSCI, Sustainalytics, Refinitiv, RobecoSAM, and KLD are based on a total of 709 indicators. These indicators form a taxonomy of 65 categories according to the allocation rule of the “Aggregate Confusion” research project. This taxonomy was developed using a bottom-up approach. Annex 12 lists the categories of the taxonomy by “Aggregate Confusion,” including the number of assigned indicators of the rating vendors. It is clear that Refinitiv with 282 and Sustainalytics with 163 use the most indicators overall. RobecoSAM, KLD, and MSCI, with a total of 80, 78, and 68 indicators, respectively, are still ahead of Vigeo Eiris with 38 indicators. The extent to which the individual rating vendors take the categories into account is also different. Sustainalytics and Refinitiv consider the most categories of the taxonomy with 57 and 54, respectively, followed by KLD and RobecoSAM with 40 and 39 categories, respectively. Vigeo Eiris and MSCI each only map 28 categories through their indicators. Furthermore, the indicators of the individual rating vendors are not evenly distributed across the categories. In the case of Sustainalytics, for example, it is noticeable that, with 21 indicators, a large share is allotted to the supply chain category. At RobecoSAM, Vigeo Eiris, and KLD, on the other hand, the indicators are more evenly distributed across the relevant categories. In the case of Refinitiv and MSCI, the strong presence of the unclassified category is again striking. This category includes indicators on topics that are only dealt with by one rating vendor. From the perspective of the categories, it is also noticeable that there are some categories, such as biodiversity, that are taken into account by all the vendors. This suggests a kind of lowest common denominator of categories. However, there are also categories, such as taxes, that are not considered by all vendors.9 Berg, F., Koelbel, J. F., & Rigobon, R. (2020). Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. The Divergence of ESG Ratings. MIT Sloan School Working Paper, 1-63.

According to the taxonomy of the SASB, there are 27 categories. However, the total of 709 indicators from Vigeo Eiris, MSCI, Sustainalytics, Refinitiv, RobecoSAM, and KLD can also be classified into this taxonomy in a top-down process. Annex 13 lists the categories of the taxonomy by the SASB, including the number of assigned indicators of the rating vendors. Considering this taxonomy, KLD and Refinitiv take into account the most categories with 23, closely followed by Sustainalytics and RobecoSAM with 22 categories each. MSCI and Vigeo Eiris only consider 18 and 17 categories, respectively. Overall, the distribution of the indicators across the relevant categories appears even. However, the strong concentration of Refinitiv, MSCI, and Sustainalytics in unclassified is striking.9 Berg, F., Koelbel, J. F., & Rigobon, R. (2020). Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. The Divergence of ESG Ratings. MIT Sloan School Working Paper, 1-63.

The taxonomy forms the basis for the direct comparability of the measurements and weights of the indicators used by the ESG rating vendors. Since the measurements and the units of the indicator values, in particular, are not made transparent by the rating vendors, a comparison at this level is difficult to implement. Nonetheless, it can generally be stated that considerable measurement divergences exist between the rating vendors. This is made clear by the low correlation levels between the category values of the taxonomies determined by the “Aggregate Confusion” research project and the SASB. The corresponding correlation tables are shown in Annexes 14 and 15. Based on the taxonomy and the category values of the rating values, it is possible to further determine the respective aggregation rules and category weightings of the rating vendors. This was carried out by the “Aggregate Confusion” research project using non-negative least squares regressions based on the taxonomy of the “Aggregate Confusion” research project and the that by the SASB. These are linear approximations to the aggregation rules and weights of the individual rating vendors based on normalized data.9 Berg, F., Koelbel, J. F., & Rigobon, R. (2020). Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. The Divergence of ESG Ratings. MIT Sloan School Working Paper, 1-63.

In Annex 16, the regression results of the taxonomy by the “Aggregate Confusion” research project are attached. Overall, the high quality of the regression models can be determined from the regression results for all the rating vendors. It should also be noted that a highly significant correlation with the ESG rating was found for some categories for all the rating vendors. Accordingly, the supply chain, environmental management system, and green products categories are the most significant for Sustainalytics’ ESG rating. For RobecoSAM, the regression results indicate a high significance of the employee development, climate risk management, and resource efficiency categories. The rating vendor Refinitiv assigns a high value to the board, resource efficiency, and remuneration categories. At Vigeo Eiris, the environmental policy, diversity, and health and safety categories come to the fore. The three most important categories for MSCI’s ESG rating are product safety, employee development, and corruption. Finally, the rating vendor KLD should be mentioned, whose most important criteria are climate risk management, remuneration, and product safety. From the perspective of the categories, it becomes clear that there are only a few overlaps among the most important categories of the respective rating vendors. There are only five overlaps between two rating vendors in each case. These include the climate risk management, employee development, product safety, remuneration, and resource efficiency categories. In contrast, the regressions lead to the observation that some categories, such as clinical trials, are not of great importance for any of the vendors with regard to their ESG ratings.9 Berg, F., Koelbel, J. F., & Rigobon, R. (2020). Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. The Divergence of ESG Ratings. MIT Sloan School Working Paper, 1-63.

The regressions using the SASB taxonomy show similar results, which are attached in Annex 17. Here, too, the quality of the regression models is high across all the rating vendors, and highly significant correlations across the ESG ratings are found for some categories for all the rating vendors. With regard to Sustainalytics, the ecological impacts, supply chain management, and GHG emissions categories are the most significant. The rating vendor RobecoSAM assigns a high value to the employee engagement, diversity and inclusion, ecological impacts, and physical impacts of climate change categories. Refinitiv’s regression results indicate a high significance of the employee engagement, diversity and inclusion, materials sourcing and efficiency, and product design and lifecycle management categories. For the ESG rating of Vigeo Eiris, the employee engagement, diversity and inclusion, ecological impacts, and labor practices categories are most important. For MSCI, the product design and lifecycle management, product quality and safety, and ecological impacts categories come to the fore. The three most important categories for KLD’s ESG rating are human rights and community relations, business ethics, and physical impacts of climate change. From a category perspective, this taxonomy shows some overlap among the main categories of the respective rating vendors. These are within the ecological impacts, employee engagement, diversity and inclusion, physical impacts of climate change, and product design and lifecycle management categories.9 Berg, F., Koelbel, J. F., & Rigobon, R. (2020). Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. The Divergence of ESG Ratings. MIT Sloan School Working Paper, 1-63.

3 Processes, measures, and tools

Sustainable finance and investment can take five different forms: socially responsible investment, impact investment, ethical investment, responsible investment, and ESG-backed investment. By investing in organizations that meet the minimum standards of social and environmental responsibility, long-term returns are targeted, which is the case with socially responsible investments. In this case, fundamental values, such as human rights and environmental friendliness, are also the focus of the investment 21 Landier, A., & Nair, V.B. (2009). Investing for Change: Profit from Socially Responsible Investment. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. . Investments that additionally aim to achieve social and environmental impacts are called impact investments 22 Global Impact Investing Network (n. d.). GIIN Initiative for Institutional Impact Investment. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://thegiin.org/giin-initiative-for-institutional-impact-investment . Ethical investment occurs when, in addition to a good return, ethical values, such as moral, social, or religious values, are also the investor’s target 23 Corporate Finance Institute (CFI) Education Inc. (n. d.). Ethical Investment. Retrieved 29/09/2021: https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/trading-investing/ethical-investing/ . The importance of ESG factors and the long-term health and stability of the market is recognized and acknowledged by investors in responsible investing 24 University of Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (2021). What is responsible investment?. Retrieved 29/08/2021: https://www.cisl.cam.ac.uk/business-action/sustainable-finance/investment-leaders-group/what-is-responsible-investment .

To understand sustainable finance and investment, it is important to know what ESG considerations are. The environmental aspect of considerations can be a part of the internal company, the external view towards the customers, and the promotion of environmental projects, independent of customer interests2 Frese, M., & Colsman, B. (2018). Nachhaltigkeitsreporting für Finanzdienstleister. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer. . This can include pollution prevention, climate change mitigation, and biodiversity conservation3 European Commission (2021). Overview of sustainable finance. Retrieved 24/08/2021: https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/banking-and-finance/sustainable-finance/overview-sustainable-finance_en . Another aspect is the social aspect, where again the external view is present, dealing with society and the customers, as well as the internal view of the employees2 Frese, M., & Colsman, B. (2018). Nachhaltigkeitsreporting für Finanzdienstleister. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer. . In terms of content, the external aspect deals with community investment and human rights issues, while the internal aspect deals with labor relations and inequality issues3 European Commission (2021). Overview of sustainable finance. Retrieved 24/08/2021: https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/banking-and-finance/sustainable-finance/overview-sustainable-finance_en . Last but not least there are governance considerations. Three dimensions also exist here: one regarding society in general, an internal one focusing on the company’s own employees, and an external one concerning the customers2 Frese, M., & Colsman, B. (2018). Nachhaltigkeitsreporting für Finanzdienstleister. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer. . The main focus is on employee relations, management structures, and executive remuneration. It “plays a fundamental role in ensuring the inclusion of social and environmental considerations in the decision-making process”3 European Commission (2021). Overview of sustainable finance. Retrieved 24/08/2021: https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/banking-and-finance/sustainable-finance/overview-sustainable-finance_en .

The European Commission set up an action plan to finance sustainable growth. It includes two important propositions related to sustainable finance. It aims to strengthen financial stability by addressing ESG factors. Furthermore, it aims to enhance the contribution of the financial sector to sustainable and inclusive growth by financing the long-term needs of society25 European Commission (2018). Action Plan: Financing Sustainable Growth. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52018DC0097&from=EN .

One option for sustainable finance and investment is sustainable real estate. Since the savings potential in this sector is very high, investments in sustainable real estate are also attractive for climate protection reasons 26 Hasenhüttl, S., & Muner-Sammer, K. (2020). Die Bedeutung und die aktuelle Entwicklung der grünen Investments. In: Sihn-Weber, A., & Fischler, F. (Ed.). pp.163-173. CSR und Klimawandel – Unternehmenspotenziale und Chancen einer nachhaltigen und klimaschonenden Wirtschaftstransformation. Berlin, Germany: Springer. . Sustainable real estate has better or more sustainability features than conventional buildings. An example of this is a low-energy house, which refers to the energy quality of the building 27 Gromer, C. (2012). Die Bewertung von nachhaltigen Immobilien – Ein kapitalmarkttheoretischer Ansatz basierend auf dem Realoptionsgedanken. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer. . Sustainable real estate funds also exist, where the international focus is on investments in social infrastructure, for example, in schools or nursing homes 26 Hasenhüttl, S., & Muner-Sammer, K. (2020). Die Bedeutung und die aktuelle Entwicklung der grünen Investments. In: Sihn-Weber, A., & Fischler, F. (Ed.). pp.163-173. CSR und Klimawandel – Unternehmenspotenziale und Chancen einer nachhaltigen und klimaschonenden Wirtschaftstransformation. Berlin, Germany: Springer. .

Commitment offers another possibility for sustainable finance and investment. Shareholders exercise their rights, for example, their voting rights, thereby exerting indirect influence on company reporting through company law28 Lange, M. (2020). Sustainable Finance: Nachhaltigkeit durch Regulierung? (Teil 2). Zeitschrift für Bank- und Kapitalmarktrecht, 261-271. . Shareholders can hold individual discussions with the company’s management or join forces, whereby it should be noted that the influence increases with the volume of the capital behind them. Engagement can be an important tool to steer companies in a sustainable direction, such as with regard to increased climate protection efforts 26 Hasenhüttl, S., & Muner-Sammer, K. (2020). Die Bedeutung und die aktuelle Entwicklung der grünen Investments. In: Sihn-Weber, A., & Fischler, F. (Ed.). pp.163-173. CSR und Klimawandel – Unternehmenspotenziale und Chancen einer nachhaltigen und klimaschonenden Wirtschaftstransformation. Berlin, Germany: Springer. .

Beyond that, there is impact investment. These “are investments made into companies, organisations, and funds with the intention to generate social and environmental impact alongside a financial return” 22 Global Impact Investing Network (n. d.). GIIN Initiative for Institutional Impact Investment. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://thegiin.org/giin-initiative-for-institutional-impact-investment . The “Deka-Nachhaltigkeit Impact Aktien” fund concept can be cited here as an example. This actively managed global fund invests exclusively in securities issued by companies that offer attractive returns and are considered responsible and sustainable according to selected criteria. The investment policy of this investment fund aims to exploit the opportunities and reduce the risks of environmental, social, and economic developments in order to generate medium- to long-term capital growth 29 Deka Investments (2021). Fondsporträt Deka-Nachhaltigkeit Impact Aktien CF. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://www.deka.de/mms/LU2109588199.pdf . It will invest in companies that provide ways to achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through their services and products. The UN SDGs are important for measuring the impact of fund investments as they are used as a guideline. Companies that do not meet the fund’s minimum sustainable criteria will not be considered for the selection of securities 30 Deka Investments (2021). Jahresbericht zum 31.Mai 2021 – Deka-Nachhaltigkeit Impact Aktien. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://www.deka.de/mms/DekaNachhaltigkeitImpactAktien_JB.pdf . The sustainable minimum criteria are based on the principles of the UN Global Compact, which deal with human rights and labor standards as well as the environment and the prevention of corruption 30 Deka Investments (2021). Jahresbericht zum 31.Mai 2021 – Deka-Nachhaltigkeit Impact Aktien. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://www.deka.de/mms/DekaNachhaltigkeitImpactAktien_JB.pdf 31 Global Compact Network Germany (n. d.). United Nations Global Compact. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://www.globalcompact.de/en/about-us/united-nations-global-compact . The “Deka-Nachhaltigkeit Impact Aktien,” which were issued for the first time on 02 June 2020, achieved a performance of plus 46.90% within one year30 Deka Investments (2021). Jahresbericht zum 31.Mai 2021 – Deka-Nachhaltigkeit Impact Aktien. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://www.deka.de/mms/DekaNachhaltigkeitImpactAktien_JB.pdf . These three initiatives concern investments, a core business of the financial industry 26 Hasenhüttl, S., & Muner-Sammer, K. (2020). Die Bedeutung und die aktuelle Entwicklung der grünen Investments. In: Sihn-Weber, A., & Fischler, F. (Ed.). pp.163-173. CSR und Klimawandel – Unternehmenspotenziale und Chancen einer nachhaltigen und klimaschonenden Wirtschaftstransformation. Berlin, Germany: Springer. .

The following measures concern a second core business of the finance industry: financing, with funding flows to be directed towards low-carbon industries 26 Hasenhüttl, S., & Muner-Sammer, K. (2020). Die Bedeutung und die aktuelle Entwicklung der grünen Investments. In: Sihn-Weber, A., & Fischler, F. (Ed.). pp.163-173. CSR und Klimawandel – Unternehmenspotenziale und Chancen einer nachhaltigen und klimaschonenden Wirtschaftstransformation. Berlin, Germany: Springer. . In 2008, the World Bank published green bonds for the first time. The market is still growing in popularity and is expanding rapidly 32 Li, Z., Tang, Y., Wu, J., Zhang, J., & Lv, Q. (2020). The Interest Costs of Green bonds: Credit Ratings, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Certification. Emerging Markets, Finance & Trade, 56, 2679-2692. . Any type of bond instrument may qualify as a green bond if its proceeds exclusively finance or refinance, in whole or in part, existing and/or new eligible green projects. In addition, federally eligible projects must comply with the core components of the green bond principles 33 ICMA (2017). The Green Bond Principles 2017. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Regulatory/Green-Bonds/GreenBondsBrochure-JUNE2017.pdf : the use of emission proceeds and processes for project evaluation and selection as well as the management of proceeds and reporting 34 ICMA (2018). The Green Bond Principles 2018. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwiMgsmJ-tHyAhVFP-wKHb4DA-0QFnoECAIQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.icmagroup.org%2Fassets%2Fdocuments%2FRegulatory%2FGreen-Bonds%2FTranslations%2F2018%2FGerman-GBP_2018-06.pdf&usg=AOvVaw30ZX4dx52GFKMQ4hAI0VK7 . Since green bonds promise to finance sustainable projects, the actual implementation of ecological or climate-friendly projects is very important to maintain the credibility and status of green bonds. However, the problem is that there is no common definition of sustainably classified activities or projects. There are voluntary definition approaches, but they are not usually generally valid26 Hasenhüttl, S., & Muner-Sammer, K. (2020). Die Bedeutung und die aktuelle Entwicklung der grünen Investments. In: Sihn-Weber, A., & Fischler, F. (Ed.). pp.163-173. CSR und Klimawandel – Unternehmenspotenziale und Chancen einer nachhaltigen und klimaschonenden Wirtschaftstransformation. Berlin, Germany: Springer. . In the year 2019, there was a global record volume of green bond issuance worldwide at 257.70 billion USD. Compared to the previous year, this corresponds to growth of 51%. The European market was the frontrunner, accounting for 45% of global issuance. However, the USA, China, and France were the three countries with the greenest bond issuances. Of the global issuances in 2019, these three countries accounted for 44% 35 Climate Bonds Initiative (2020). 2019 Green Bond Market Summary. Retrieved 27.08.2021: https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/2019_annual_highlights-final.pdf .

Another possibility for sustainable finance is crowd investing. In Germany, this type of financing has been around since 2011. In crowd investing, an issuer collects small contributions from several investors via an internet platform 36 Weitnauer, W. (2019). Handbuch Venture Capital – Von der Innovation zum Börsengang. 6. Edn. Munich, Germany: C. H. Beck. . Thus, this financial instrument enables many investors to finance a project or a company26 Hasenhüttl, S., & Muner-Sammer, K. (2020). Die Bedeutung und die aktuelle Entwicklung der grünen Investments. In: Sihn-Weber, A., & Fischler, F. (Ed.). pp.163-173. CSR und Klimawandel – Unternehmenspotenziale und Chancen einer nachhaltigen und klimaschonenden Wirtschaftstransformation. Berlin, Germany: Springer. . In most cases, the issuers are young start-up companies that give their investors a share in the issuer’s enterprise value or profits in return for their investment 36 Weitnauer, W. (2019). Handbuch Venture Capital – Von der Innovation zum Börsengang. 6. Edn. Munich, Germany: C. H. Beck. . On the one hand, crowd investing involves a high level of risk for investors, but on the other hand, high returns can be expected. It often involves investments in renewable energies, such as photovoltaics or wind energy26 Hasenhüttl, S., & Muner-Sammer, K. (2020). Die Bedeutung und die aktuelle Entwicklung der grünen Investments. In: Sihn-Weber, A., & Fischler, F. (Ed.). pp.163-173. CSR und Klimawandel – Unternehmenspotenziale und Chancen einer nachhaltigen und klimaschonenden Wirtschaftstransformation. Berlin, Germany: Springer. .

Companies acting as role models and exemplifying sustainable behavior are of significance. In combination with, for example, training and behavioral change, this already represents a sustainable process that has positive social and environmental impacts. The sustainable behavior of a company’s employees can lead to them also changing their behavior in everyday life, contributing to the shift towards an improved society and a careful approach to ecology 2 Frese, M., & Colsman, B. (2018). Nachhaltigkeitsreporting für Finanzdienstleister. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer. .

However, it is important to ensure that no greenwashing is practiced as such behavior can have incalculable negative consequences for the entire business operation 2 Frese, M., & Colsman, B. (2018). Nachhaltigkeitsreporting für Finanzdienstleister. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer. . According to the taxonomy regulation, greenwashing occurs when a financial product is advertised as environmentally friendly even though it does not meet basic environmental standards, thereby gaining an unfair competitive advantage 37 Europäischen Union (2020). Verordnung (EU) 2020/852 des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates vom 18. Juni 2020. . As the taxonomy regulation defines the concept of environmental sustainability in concrete terms, it attempts to provide a uniform EU-wide standard for environmentally sustainable investments and to prevent greenwashing 38 Geier, B., & Hombach, K. (2021). ESG: Regelwerke im Zusammenspiel. Zeitschrift für bank- und Kapitalmarktrecht, 6-14. .

4 Drivers and barriers

Various criteria are driving the trend towards sustainable investment and financing. This enables customers as well as investors and companies to select investment products based on their values and priorities 39 EY Global (2020). Why sustainable investing matters. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.ey.com/en_gl/financial-services/why-sustainable-investing-matters . These include policy and regulatory drivers, industry collaborations, customer drivers, and market drivers, all of which vary across different countries 40 Global Sustainable Investment (GSI) Alliance (2021). Global Sustainable Investment Review 2020. Retrieved 28/08/2021: http://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/GSIR-2020.pdf .

4.1 Policy and regulatory drivers

Policy and regulatory drivers depend on countries’ policies and objectives. The changing administrations in the USA have had severe impacts on the regulatory policy environment regarding sustainable investing. While the administration under President Trump pursued limiting sustainable investing, the current administration under President Biden is working towards reversing and mitigating these measures. However, despite the change in policy direction in the USA, investor interest in sustainable investment has increased (as seen in Figure 4). Legislation is currently planned or in the works that will allow ESG criteria to be included in plans governed by Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). Since the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) requested information on climate risks and ESG disclosures in March 2021, it is assumed that the agency is working on a regulatory proposal for mandatory climate change disclosure by issuers. The new US administration has set itself the goal of tackling specific ESG issues, such as climate change and strengthening workers’ rights 40 Global Sustainable Investment (GSI) Alliance (2021). Global Sustainable Investment Review 2020. Retrieved 28/08/2021: http://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/GSIR-2020.pdf. .

In the EU, the most influential drivers regarding policy and regulations are measures taken by the European Commission. The 2018 Sustainable Finance Action Plan and the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), in particular, provide a regulation on the disclosure of sustainable financial products among other things. This is accompanied by new legal definitions that have a significant impact on the ESG/responsible investment market. The regulation requires institutional investors and asset managers, as well as advisors, to disclose how they integrate sustainability risks and negative impacts at the corporate level in order to ultimately classify these ESG products. ESG integration should thus become part of the practice regarding all financial products 25 European Commission (2018). Action Plan: Financing Sustainable Growth. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52018DC0097&from=EN . Another regulatory measure is Directive 2014/95 of the European Parliament and Council. This obliges large companies to regularly disclose reports on the social and environmental impacts of their operations 41 European Parliament and the Council of the European Union (2014). Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014. . Furthermore, there is currently a proposed Markets in Financial Instruments Directive II (MiFID II). Based on this, financial advisors will have to ask each client about their sustainability preferences and offer products accordingly, so that sustainability issues will always be taken into account 42 European Securities and Markets Authority (2019). Final Report. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/esma35-43-1737_final_report_on_integrating_sustainability_risks_and_factors_in_the_mifid_ii.pdf. A regulation on taxonomy in the EU came into force in 2020 and uses overarching conditions to set out the framework for economic activities that companies need to meet in order to be considered environmentally sustainable 43 European Parliament and the Council of the European Union (2020). Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the council of 18 June 2020. . Another important EU directive to be implemented by the individual countries is the guidelines on reporting climate-related information, which contains the double materiality perspective. According to this, companies and investors must report not only on risks and opportunities, but also on issues that have a temporal and geographical impact on environmental and social goals. Environmental goals regarding climate change mitigation, climate adaptation, water, the circular economy, pollution, and biodiversity are defined 44 European Commission (2019). Guidelines on reporting climate-related information. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://ec.europa.eu/finance/docs/policy/190618-climate-related-information-reporting-guidelines_en.pdf . Overall, the conditions are thus made consumer-friendly so that it becomes more transparent if and to what extent European companies operate sustainably.

In China, sustainable investment and finance are also being promoted through policy and regulatory measures. The China Banking Regulatory Commission’s (CBIRC) sustainable credit guideline was introduced in 2012 44 European Commission (2019). Guidelines on reporting climate-related information. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://ec.europa.eu/finance/docs/policy/190618-climate-related-information-reporting-guidelines_en.pdf and was the first of its kind for green finance at the national level 40 Global Sustainable Investment (GSI) Alliance (2021). Global Sustainable Investment Review 2020. Retrieved 28/08/2021: http://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/GSIR-2020.pdf . Banking institutions are encouraged by this regulation to foster green loans and to introduce stronger environmental and social risk management45 Green Finance Platform (2012). China’s Green Credit Guidelines. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://www.greenfinanceplatform.org/policies-and-regulations/chinas-green-credit-guidelines . The Chinese government’s ambitions to further develop renewable energy and promote electric vehicles are expected to increase inflows into ESG-related exchange traded funds (ETFs) and contribute to overall asset growth 46 Scanlan, D. (2021). After 1,700% Asset Growth, China Poised to Lead ESG Push in Asia. Retrieved 29/08/2021: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-01-19/after-1-700-asset-growth-china-poised-to-lead-esg-push-in-asia .

Overall, many countries are taking different measures to encourage companies to invest and finance sustainably and to make the content of their products more transparent to consumers. In view of the development of climate change, it is expected that the guidelines and regulations will be increasingly tightened or that new ones will come into force to achieve net-neutrality 40 Global Sustainable Investment (GSI) Alliance (2021). Global Sustainable Investment Review 2020. Retrieved 28/08/2021: http://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/GSIR-2020.pdf .

Another driver is legal actions taken against unsustainable companies and legislation. Following the Paris Agreement, which became legally binding in 2016, numerous activist groups have initiated legal action against companies and governments. In a recent ruling in the Netherlands, the oil giant Royal Dutch Shell was ordered to reduce its emissions by 45% compared to 2019 by 2030 47 Harrabin, R. (2021). Shell: Netherlands court orders oil giant to cut emissions. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-57257982 . This landmark ruling is among the first where a company has been sued over environmental damage that has not yet been caused. Investors must therefore be prepared for such significantly unsustainable companies being ordered by the courts to reduce their emissions. However, this ruling did not seem to have an impact on the share value of Royal Dutch Shell, which after a drop of about 50% in 2020 is now stable albeit at a lower level 48 Börse Frankfurt (n.d.). Royal Dutch Shell. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.boerse-frankfurt.de/equity/royal-dutch-shell . In Germany, a lawsuit filed by a number of activists before the Federal Constitutional Court was also successful. The court found that the country’s current climate protection law is incompatible with fundamental rights because it lacks plans to reduce emissions from 2030. Thus, the plaintiffs’ liberty rights would be violated as emission reduction burdens were pushed into the future 49 Bundesverfassungsgericht (2021). Costitutional complaints against the Federal Climate Change Act partially successful. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.bundesverfassungsgericht.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/EN/2021/bvg21-031.html .

Companies and their stakeholders must therefore prepare themselves for the fact that organizations will have to comply with stricter requirements and legislation regarding their emissions and sustainability in general in order for countries to meet the global climate targets of the Paris Agreement.

4.2 Industry drivers

Industry initiatives can drive sustainable investments and financing. Improved ESG outcomes can be achieved, for example, by promoting voluntary labels for sustainable funds. National labels of this kind already exist in some countries, and more than 1,500 investment funds in Europe already have at least one of these labels. In March 2021, the funds were worth a total of 827 billion EUR. Another driver is collaborative initiatives. The European financial services sector wants such collaboration in the future in order to standardize and facilitate the flow of data. The aim is to establish a European ESG template to better respond to client requests. A UN alliance is also promoting sustainable investment. In the Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance, portfolios are adapted to the 1.5° Celsius scenario 40 Global Sustainable Investment (GSI) Alliance (2021). Global Sustainable Investment Review 2020. Retrieved 28/08/2021: http://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/GSIR-2020.pdf .

In 2020, the Racial Justice Investing initiative published a statement following the murder of George Floyd and several other black citizens of the USA. In the statement, numerous investors commit to combating systemic racism and call on other investors to do the same. Here, therefore, a social movement opposed to extreme social injustice and police violence against black people was driving accountable financing to achieve racial equity and justice 50 Racial Justice Investing (2020). Investor Statement of Solidarity to Address Systemativ Racism and Call to Action. Retrieved 29/08/2021: https://www.racialjusticeinvesting.org/our-statement . Alliances for entrepreneurial engagement are becoming an increasingly used tool for investors. The most popular ESG topics in shareholder proposals are political activity, labor and equal employment opportunity, and climate change/carbon, followed by executive pay and independent board chairs 51 US SIF (2020). Report on US Sustainable and Impact Investing Trends 2020. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.ussif.org/files/US%20SIF%20Trends%20Report%202020%20Executive%20Summary.pdf . Social factors or inequalities are therefore a key driver of social investment alongside climate change.

In 2018, the Asset Management Association of China published China’s first self-regulatory standard on sustainable investment for the asset management industry. The Green Investment Guidelines are still in the trial phase. They are intended to encourage fund management companies to focus on environmental sustainability and create awareness of environmental risks. Going forward, the scope and approaches of sustainable investments will be defined, and sustainable funds will be pushed. In the long term, the aim is to improve the environmental performance of investment activities in order to achieve green sustainable economic growth 52 Green Finance Platfrom (2018). China’s Green Investment Guidelines. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://www.greenfinanceplatform.org/policies-and-regulations/chinas-green-investment-guidelines .

Drivers are therefore also emerging globally from the financial sector, with companies taking initiatives to help shape sustainable investment and financing.

4.3 Customer and market drivers

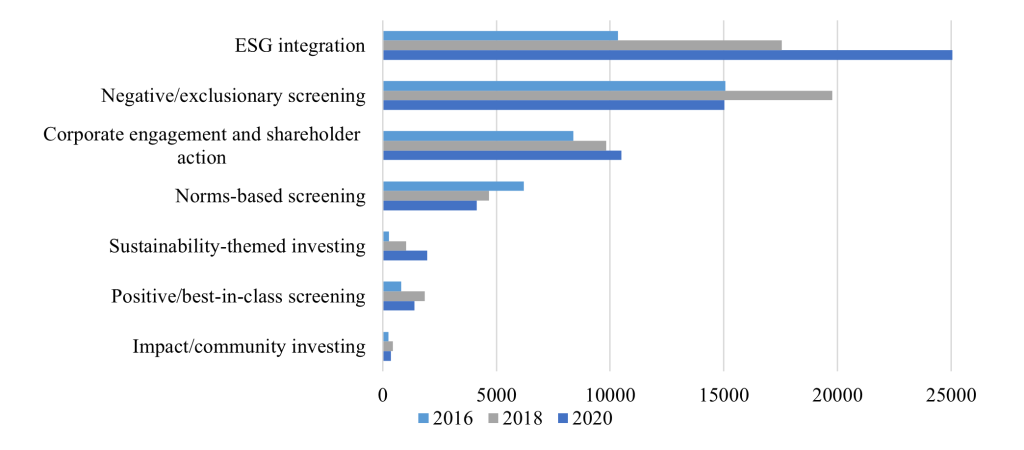

In the face of the changing climate, companies will have to adapt to new circumstances in the near future. A rethinking of economic activity is necessary in order to adapt to the new conditions caused by the effects of climate change53 IPCC (2021). Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S. L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M. I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T. K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. In Press. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Full_Report.pdf . The latter and public discussions on social injustices change preferences and the behavior of customers, which are noticeable and have an impact on the financial market. Investor behavior and demand regarding the investment market, especially that of younger generations, is in flux39 EY Global (2020). Why sustainable investing matters. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.ey.com/en_gl/financial-services/why-sustainable-investing-matters . Climate change is one of the most important criteria and a driver of sustainable finance. Others include corporate political activity, labor and equal employment opportunity, executive pay, independent board chairs, and human rights51 US SIF (2020). Report on US Sustainable and Impact Investing Trends 2020. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.ussif.org/files/US%20SIF%20Trends%20Report%202020%20Executive%20Summary.pdf . Numerous equity funds are now available, most of which have increased in volume and performed well recently.54 Fondsweb (n.d.). NL (L) Global Sustainable Equity P Cap. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.fondsweb.com/de/LU0119216553 55 Fondsweb (n.d.). DPAM L Bonds Emerging Markets Sustainable B. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.fondsweb.com/de/LU0907927338 56 Fondsweb (n.d.). LO Funds – Generation Global (EUR) P D. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.fondsweb.com/de/LU0428704554 The Global Sustainable Investment Alliance shows the development of different sustainable strategies in investment, as seen in Figure 3.

Except for investments in norms-based screening, all the strategies showed growth in the given period. The biggest growth however can be seen in sustainability-themed investing, which grew by 63% globally over the 4 years. Nevertheless, the strategy with the largest initial sum also recorded solid growth of 25%. Just under half (48%) of the investment sum comes from the USA and about a third from Europe (34%). It should be noted, however, that due to different definitions and regulations for sustainable investment, a comparison of the amounts cannot be made easily 40 Global Sustainable Investment (GSI) Alliance (2021). Global Sustainable Investment Review 2020. Retrieved 28/08/2021: http://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/GSIR-2020.pdf .

Sustainable and responsible investment options saw strong demand from retail investors in the first half of 2020 in Europe. With the help of MiFID II, the European Commission wants to further increase the offer of ESG products for retail clients 40 Global Sustainable Investment (GSI) Alliance (2021). Global Sustainable Investment Review 2020. Retrieved 28/08/2021: http://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/GSIR-2020.pdf . A record number of 505 new ESG funds were launched, and 250 conventional funds were redeployed in the European region to meet the rapidly growing demand 57 Morningstar Manager Research (2021). European Sustainable Funds Landscape: 2020 in Review. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://www.morningstar.com/content/dam/marketing/emea/uk/European_ESG_Fund_Landscape_2020.pdf?utm_source=eloqua&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=&utm_content=18267 .

This trend can also be seen in the USA, where 4.6 trillion USD of ESG assets were managed for retail clients in 2020, up from 3 trillion USD in 2018, with an increase of over 50%. Furthermore, sustainable investment strategies in general increased by 42%. In terms of volume, the assets grew from 12.0 trillion USD at the beginning of 2018 to 17.1 trillion USD at the beginning of 2020 51 US SIF (2020). Report on US Sustainable and Impact Investing Trends 2020. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.ussif.org/files/US%20SIF%20Trends%20Report%202020%20Executive%20Summary.pdf .

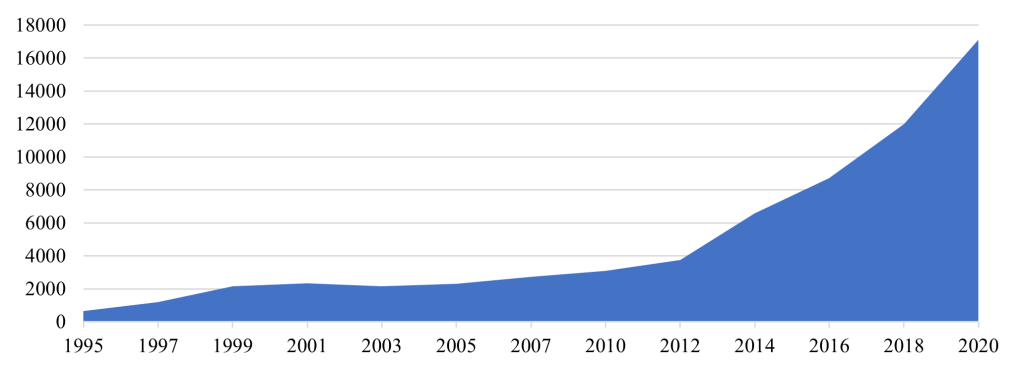

Figure 4 shows the rapid growth of sustainable investing during recent years. US sustainable investment has experienced an annual growth rate of 14%. However, when only considering the time period since 2012, the annual growth rate is 21%. In total, one third of professionally managed assets used sustainable investment in 2020 51 US SIF (2020). Report on US Sustainable and Impact Investing Trends 2020. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.ussif.org/files/US%20SIF%20Trends%20Report%202020%20Executive%20Summary.pdf . This growth in the volume of investment shows the increasing demand. The investment company BlackRock assumes that the sum of the assets of sustainable mutual funds and ETFs will continue to rise in the near future 58 BlackRock (n.d.). Sustainable investing. Retrieved 29/08/2021: https://www.blackrock.com/us/individual/investment-ideas/sustainable-investing .

Already at the end of 2015, the People’s Bank of China started to distribute green financial bonds on the Chinese market. What can be categorized as green financial bonds was defined in the Green Bond Endorsed Project Catalogue 59 Green Finance Committee of China Society of Finance and Banking (2015). Preparation Instructions on Green Bond Endorsed Project Catalogue. Retrieved 29/08/2021: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwjSyeTPjdbyAhXjhf0HHerWDUcQFnoECAYQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.icmagroup.org%2Fassets%2Fdocuments%2FRegulatory%2FGreen-Bonds%2FPreparation-Instructions-on-Green-Bond-Endorsed-Project-Catalogue-2015-Edition-by-EY.pdf&usg=AOvVaw1-d1zasBwdf4p7vC-7Mg1i . The catalogue was updated in mid-2021 to align with national and international standards40 Global Sustainable Investment (GSI) Alliance (2021). Global Sustainable Investment Review 2020. Retrieved 28/08/2021: http://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/GSIR-2020.pdf .

4.4 Barriers

As previously mentioned, sustainability ratings pose problems for investors in terms of transparency. ESG risks and ratings as well as regulations can differ between companies and industries 60 MSCI (n.d.). How do MSCI ESG Ratings work? Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.msci.com/our-solutions/esg-investing/esg-ratings . Furthermore, ESG ratings can vary with different rating vendors, which is mainly caused by divergences in measurements. Inconsistencies between rating vendors can also lead to different ratings. These are particularly pronounced in the assessment of human rights and product safety. Furthermore, differences in the weightings of the criteria should be noted. In addition, a rater effect was found in a study by Berg et al. (2019). According to this, raters tend to appraise companies equally well in different categories 61 Berg, F., Koelbel, J.F., Rigobon, R. (2019) Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. MIT Sloan Working Paper 5822-19. . This lack of consistency in uniform ratings and regulations makes it easier for companies to positively influence and possibly embellish their ESG ratings. Greenwashing is being countered by increasing regulations on sustainable investments 57 Morningstar Manager Research (2021). European Sustainable Funds Landscape: 2020 in Review. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://www.morningstar.com/content/dam/marketing/emea/uk/European_ESG_Fund_Landscape_2020.pdf?utm_source=eloqua&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=&utm_content=18267 . Nevertheless, regulations for sustainable investment, which are still in the development phase, lead to insufficiently defined criteria that can be interpreted and manipulated in different ways. In August 2021, for example, the United States Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) started an investigation against the subsidiary of Deutsche Bank DWS, as the company is suspected of having made false statements regarding the criteria for sustainability products 62 Zeit online (2021). US-Börsenaufsicht ermittelt wegen Greenwashings gegen DWS. Retrieved 29/08/2021: https://www.zeit.de/wirtschaft/unternehmen/2021-08/deutsche-bank-tocher-dws-url-dws-fondsanbieter-deutsche-bank-tochter-us-boersenaufsicht-ermittlungen-nachhaltigkeitsangaben?utm_referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com . After the announcement of the SEC’s investigation, the share value of DWS fell by around 14% 63 Wall Street Journal (n.d.). DWS Group GmbH & Co. KGaA. Retrieved 29/08/2021: https://www.wsj.com/market-data/quotes/xe/xetr/DW , causing the company’s market capitalization to drop by around 1 billion EUR 64 Manager Magazin (2021). Greenwashing-Verdacht kostet DWS eine Milliarde Euro Börsenwert. Retrieved 29/08/2021: https://www.manager-magazin.de/finanzen/boerse/dws-aktie-bricht-nach-bericht-ueber-sec-ermittlung-wegen-greenwashing-ein-a-2a984afd-32f1-4456-8656-23d99a074479 . An attempt at greenwashing can consequently have significant consequences for a company, even if it is only a suspicion and the intent has not yet been proven. However, it can be assumed that with increasing requirements and more precision regarding the terminology of sustainable investment, greenwashing will become increasingly difficult and more easily prevented.

One barrier to sustainable investment is the lower returns in relation to higher ESG scores when compared to companies that perform worse on ESG indicators. This could be due to higher risk or investors’ preference for companies with high ESG scores. The choice of investing in such products consequently means price premiums for investors or profit losses compared to products with a poorer ESG rating. It follows that investors are only willing to invest in companies with lower ESG ratings if in return they can expect higher returns 65 Ciciretti, R., Dalo, A., Dam, L. (2019). The Contributions of Betas versus Characteristics to the ESG Premium. CEIS Working Paper, No. 413.. Consequently, investors may continue to be attracted to higher returns from companies with low ESG ratings.

References

- 1Drost, F. M. (2021). Nachhaltiges Investment – Vor allem Privatanleger treiben den Trend zu nachhaltigen Geldanlagen an. In: Handelsblatt. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://www.handelsblatt.com/finanzen/anlagestrategie/trends/nachhaltiges-investment-vor-allem-privatanleger-treiben-den-trend-zu-nachhaltigen-geldanlagen-an/27262674.html?ticket=ST-1240903-zJ4Py6RRecaTPsJUH7Nl-ap6

- 2Frese, M., & Colsman, B. (2018). Nachhaltigkeitsreporting für Finanzdienstleister. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer.

- 3European Commission (2021). Overview of sustainable finance. Retrieved 24/08/2021: https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/banking-and-finance/sustainable-finance/overview-sustainable-finance_en

- 4Scholz, O. (2021). In: Federal Ministry of Finance. Setting the course for the financial sector: climate action and sustainability as core themes. Retrieved 24/08/2021: https://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/EN/Pressemitteilungen/2021/2021-05-05-sustainable-finance-strategy.html

- 5United Nations (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for sustainable development A/RES/70/1. Retrieved: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf

- 6Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung (2021). Agenda 2030 – Ziele für eine nachhaltige Entwicklung weltweit. Retrieved 25/08/2021: https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/themen/nachhaltigkeitspolitik/ziele-fuer-eine-nachhaltige-entwicklung-weltweit-355966

- 7Oekom (2018). Oekom Corporate Responsibility Review 2018. Retrieved 26/08/2021: https://www.issgovernance.com/file/publications/cr-review-2018-en.pdf

- 8GSIA (2021). Global Sustainable Investment Review 2020. Retrieved on 28/08/2021: http://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/GSIR-2020.pdf

- 9Berg, F., Koelbel, J. F., & Rigobon, R. (2020). Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. The Divergence of ESG Ratings. MIT Sloan School Working Paper, 1-63.

- 10Doh, J. P., Howton, S. D., Howton, S. W., & Siegel, D. S. (2010). Does the market respond to an endorsement of social responsibility? The role of institutions, information, and legitimacy. Journal of Management, 36(6), 1461-1485.

- 11World Economic Forum (2021). ESG Ecosystem Map. Retrieved on 28/08/2021: https://widgets.weforum.org/esgecosystemmap/index.html#/

- 12Eccles, R. G., & Stroehle, J. C. (2018). Exploring Social Origins in the Construction of ESG Measures. 1-36.

- 13Chatterji, A. K., Durand, R., Levine, D., & Touboul, S. (2016). Do ratings of firms converge? Implications for managers, investors and strategy researchers. Strategic Management Journal, 37. 1597-1614.

- 14Vigeo Eiris (2020). ESG Assessment Methodology. Retrieved on 28/08/2021: https://vigeo-eiris.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/VE_ESG-Assessment-Summary_2021-2.pdf

- 15MSCI ESG Research (2020). MSCI ESG Ratings Methodology. Retrieved on 28/08/2021: https://www.msci.com/documents/1296102/21901542/MSCI+ESG+Ratings+Methodology+-+Exec+Summary+Nov+2020.pdf

- 16Sustainalytics (2021). ESG Risk Ratings Methodology Abstract. Retrieved on 28/08/2021: https://connect.sustainalytics.com/hubfs/INV/Methodology/Sustainalytics_ESG%20Ratings_Methodology%20Abstract.pdf

- 17Sustainalytics (2021). Overview of Sustainalytics’ Material ESG Issues. Retrieved on 28/08/2021: https://connect.sustainalytics.com/hubfs/INV/MEI/Overview-of-Sustainalytics-Material-ESG-_Final_feb2021.pdf

- 18Refinitiv (2021). Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Scores from Refinitiv. Retrieved on 28/08/2021: https://www.refinitiv.com/content/dam/marketing/en_us/documents/methodology/refinitiv-esg-scores-methodology.pdf

- 19RobecoSAM (2021). Measuring Intangibles. Retrieved on 28/08/2021: https://www.spglobal.com/esg/csa/static/docs/measuring_intangibles_csa-methodology.pdf

- 20Delmas, M., Etzion, D., & Nairn-Birch, N. (2013). Triangulating Environmental Performance: What Do Corporate Social Responsibility Ratings Really Capture?. Academy of Management Perspectives, 27(3), 255-267.

- 21Landier, A., & Nair, V.B. (2009). Investing for Change: Profit from Socially Responsible Investment. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

- 22Global Impact Investing Network (n. d.). GIIN Initiative for Institutional Impact Investment. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://thegiin.org/giin-initiative-for-institutional-impact-investment

- 23Corporate Finance Institute (CFI) Education Inc. (n. d.). Ethical Investment. Retrieved 29/09/2021: https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/trading-investing/ethical-investing/

- 24University of Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (2021). What is responsible investment?. Retrieved 29/08/2021: https://www.cisl.cam.ac.uk/business-action/sustainable-finance/investment-leaders-group/what-is-responsible-investment

- 25European Commission (2018). Action Plan: Financing Sustainable Growth. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52018DC0097&from=EN

- 26Hasenhüttl, S., & Muner-Sammer, K. (2020). Die Bedeutung und die aktuelle Entwicklung der grünen Investments. In: Sihn-Weber, A., & Fischler, F. (Ed.). pp.163-173. CSR und Klimawandel – Unternehmenspotenziale und Chancen einer nachhaltigen und klimaschonenden Wirtschaftstransformation. Berlin, Germany: Springer.

- 27Gromer, C. (2012). Die Bewertung von nachhaltigen Immobilien – Ein kapitalmarkttheoretischer Ansatz basierend auf dem Realoptionsgedanken. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer.

- 28Lange, M. (2020). Sustainable Finance: Nachhaltigkeit durch Regulierung? (Teil 2). Zeitschrift für Bank- und Kapitalmarktrecht, 261-271.

- 29Deka Investments (2021). Fondsporträt Deka-Nachhaltigkeit Impact Aktien CF. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://www.deka.de/mms/LU2109588199.pdf

- 30Deka Investments (2021). Jahresbericht zum 31.Mai 2021 – Deka-Nachhaltigkeit Impact Aktien. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://www.deka.de/mms/DekaNachhaltigkeitImpactAktien_JB.pdf

- 31Global Compact Network Germany (n. d.). United Nations Global Compact. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://www.globalcompact.de/en/about-us/united-nations-global-compact

- 32Li, Z., Tang, Y., Wu, J., Zhang, J., & Lv, Q. (2020). The Interest Costs of Green bonds: Credit Ratings, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Certification. Emerging Markets, Finance & Trade, 56, 2679-2692.

- 33ICMA (2017). The Green Bond Principles 2017. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Regulatory/Green-Bonds/GreenBondsBrochure-JUNE2017.pdf

- 34ICMA (2018). The Green Bond Principles 2018. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwiMgsmJ-tHyAhVFP-wKHb4DA-0QFnoECAIQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.icmagroup.org%2Fassets%2Fdocuments%2FRegulatory%2FGreen-Bonds%2FTranslations%2F2018%2FGerman-GBP_2018-06.pdf&usg=AOvVaw30ZX4dx52GFKMQ4hAI0VK7

- 35Climate Bonds Initiative (2020). 2019 Green Bond Market Summary. Retrieved 27.08.2021: https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/2019_annual_highlights-final.pdf

- 36Weitnauer, W. (2019). Handbuch Venture Capital – Von der Innovation zum Börsengang. 6. Edn. Munich, Germany: C. H. Beck.

- 37Europäischen Union (2020). Verordnung (EU) 2020/852 des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates vom 18. Juni 2020.

- 38Geier, B., & Hombach, K. (2021). ESG: Regelwerke im Zusammenspiel. Zeitschrift für bank- und Kapitalmarktrecht, 6-14.

- 39EY Global (2020). Why sustainable investing matters. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.ey.com/en_gl/financial-services/why-sustainable-investing-matters

- 40Global Sustainable Investment (GSI) Alliance (2021). Global Sustainable Investment Review 2020. Retrieved 28/08/2021: http://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/GSIR-2020.pdf

- 41European Parliament and the Council of the European Union (2014). Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014.

- 42European Securities and Markets Authority (2019). Final Report. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/esma35-43-1737_final_report_on_integrating_sustainability_risks_and_factors_in_the_mifid_ii.pdf

- 43European Parliament and the Council of the European Union (2020). Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the council of 18 June 2020.

- 44European Commission (2019). Guidelines on reporting climate-related information. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://ec.europa.eu/finance/docs/policy/190618-climate-related-information-reporting-guidelines_en.pdf

- 45Green Finance Platform (2012). China’s Green Credit Guidelines. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://www.greenfinanceplatform.org/policies-and-regulations/chinas-green-credit-guidelines

- 46Scanlan, D. (2021). After 1,700% Asset Growth, China Poised to Lead ESG Push in Asia. Retrieved 29/08/2021: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-01-19/after-1-700-asset-growth-china-poised-to-lead-esg-push-in-asia

- 47Harrabin, R. (2021). Shell: Netherlands court orders oil giant to cut emissions. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-57257982

- 48Börse Frankfurt (n.d.). Royal Dutch Shell. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.boerse-frankfurt.de/equity/royal-dutch-shell

- 49Bundesverfassungsgericht (2021). Costitutional complaints against the Federal Climate Change Act partially successful. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.bundesverfassungsgericht.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/EN/2021/bvg21-031.html

- 50Racial Justice Investing (2020). Investor Statement of Solidarity to Address Systemativ Racism and Call to Action. Retrieved 29/08/2021: https://www.racialjusticeinvesting.org/our-statement

- 51US SIF (2020). Report on US Sustainable and Impact Investing Trends 2020. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.ussif.org/files/US%20SIF%20Trends%20Report%202020%20Executive%20Summary.pdf

- 52Green Finance Platfrom (2018). China’s Green Investment Guidelines. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://www.greenfinanceplatform.org/policies-and-regulations/chinas-green-investment-guidelines

- 53IPCC (2021). Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S. L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M. I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T. K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. In Press. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Full_Report.pdf

- 54Fondsweb (n.d.). NL (L) Global Sustainable Equity P Cap. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.fondsweb.com/de/LU0119216553

- 55Fondsweb (n.d.). DPAM L Bonds Emerging Markets Sustainable B. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.fondsweb.com/de/LU0907927338

- 56Fondsweb (n.d.). LO Funds – Generation Global (EUR) P D. Retrieved 27/08/2021: https://www.fondsweb.com/de/LU0428704554

- 57Morningstar Manager Research (2021). European Sustainable Funds Landscape: 2020 in Review. Retrieved 28/08/2021: https://www.morningstar.com/content/dam/marketing/emea/uk/European_ESG_Fund_Landscape_2020.pdf?utm_source=eloqua&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=&utm_content=18267

- 58BlackRock (n.d.). Sustainable investing. Retrieved 29/08/2021: https://www.blackrock.com/us/individual/investment-ideas/sustainable-investing