Authors: Lucy Beier, Natalie Fjodorow, Kristin Wortmeyer, Xizhi Lin

Last updated: January 03, 2023

1 Definition and relevance

The topic of risk, issue and crisis Management deals with issues in the future and they are indispensable for a functioning company. In the area of sustainability, issues such as a large number of affected stakeholders, a high complexity of systems, high uncertainties as well as high interdisciplinarity often arise. Especially in such areas, problems can occur at any time. With the help of risk, issue and crisis Management, these problems should be identified and resolved at an early stage.1Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 152-158.

The term risk management is understood as the preparation for an identification of a problem that has not yet occurred. The goal is to prevent the problems from arising in the first place. Issue management describes a process whereby problems in the stakeholder environment are identified, analyzed and prioritized. The principle of crisis management aims to manage problems that have already developed into a critical state. It therefore makes most sense for a company to carry out all three different types of management in order to be able to counteract problems at every stage.2Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 152-158.

With regard to risk management, a distinction is made between three different types of risk. differentiate which types of risk can occur at all. Preventable risks are internal risks that offer no strategic benefit. This type of risk is prevented by defining corporate values, setting clear limits for employee behavior and effective monitoring. The second type is strategic risks. These are risks that are taken in order to achieve higher returns. They are prevented by reducing the probability of risk events occurring and developing capabilities to manage risk events if they do occur. External risks represent the third type of risk. External threats are those that cannot be controlled. These are prevented by introducing measures to identify risks, for example scenario analyses.3Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 152-158. When risks occur in a company, they should be identified, analyzed and named as quickly as possible.4Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 152-158. For this procedure, different types of analyses are available, such as scenario analysis, the Delphi Method or business wargaming.

In issue management, the interaction between the company and its stakeholders plays a major role. An issue is understood as the discrepancy between the actions of a company and the expectations of its stakeholders. The solution is a debate to resolve the disagreement. Errors that can occur in this process manifest themselves in the unclear definition of the terms of the debate and in conflicting values and interests. Questions often cannot be answered automatically by expert knowledge. The task here is to find a solution that everyone involved can cope with.5Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stake- holder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 152-158.

Crisis management deals with the management of an existing crisis. A crisis is defined as an extreme event that can threaten the existence of the company. At the very least, it causes significant in jury, death, or financial cost, as well as serious reputational damage.6Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stake- holder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 152-158.

2 Background

When carrying out risk, issue and crisis management, it is important that the three types of analyses are coordinated with each other and thus lead to an effective way of working within the company. Furthermore, in today’s world it is of great importance to include the aspect of sustainability in the daily business.

2.1 Connection to sustainability

In business, the buzzword of the day is sustainability. The term usually has a positive connotation, but there is no uniform understanding of it. The term sustainability is used in many contexts, such as energy, mobility, corporate environmental management and climate protection. Companies are subject to globalizing and intensifying competitive pressure in terms of raw materials, costs, employees and innovation. In order to achieve medium and long-term success, the analyses and strategies within a company must be renewed with a focus on global justice.7Pufé, I. (2014). Nachhaltigkeit. UVK. Konstanz, München. p. 20. The concept of sustainability has its origins in forestry and aims to preserve the resource base and thus the economic base. In its original sense, sustainability describes the use of a regenerable natural system in such a way that this system is preserved in its essential properties and its needs can grow back in a natural way.8Pufé, I. (2014). Nachhaltigkeit. UVK. Konstanz, München. p. 34. Over time, sustainability has evolved from a troublesome eco-issue to a potential recipe for success.9Pufé, I. (2014). Nachhaltigkeit. UVK. Konstanz, München. p. 190.

For this very reason, the consideration of sustainable aspects must not be missing in the risk, issue and crisis management. Nowadays, completely different problems can develop than was the case 10 years ago. Every modern company should therefore try to act as sustainably as possible with a view to the future.

Companies can contribute significantly to the overall solution through new developments and product innovation and thus secure their own long-term competitiveness and future viability.10Mayer, K. (2020). Nachhaltigkeit: 125 Fragen und Antworten. Springer. Hofheim. p. 5. The larger the company and the greater the public interest in it, the less the company can evade or even refuse to address the issue of sustainability. But small companies also have to deal with the issue because in the long term the aim is sustainability.11Mayer, K. (2020). Nachhaltigkeit: 125 Fragen und Antworten. Springer. Hofheim. p. 25-29.

In the corporate context, sustainability is far more than just ecological or social awareness. It is fundamentally about generating profits in an environmentally friendly and socially responsible manner. Consequently, the entrepreneurial issues must include ecological, social as well as ethical basic principles in the economic decision-making process and be aware of the effects of one’s own entrepreneurial actions on both the environment and society and take responsibility for them. The core task of companies is therefore to be aware of the interests and expectations of their stakeholders and to take these into account when making decisions.12Mayer, K. (2020). Nachhaltigkeit: 125 Fragen und Antworten. Springer. Hofheim. p. 25-29.

2.2 Interaction of risk, issue and crisis management

In 2008, the World Health Organization declared the Chinese dairy scandal one of the largest food safety crises in recent history. Nearly 300 people fell ill and several infants died due to contaminated infant formula and food products. Causes of the crisis included farmers’ use of low-quality feed, traders’ addition of melamine to increase protein content, dairies’ and U.S. companies’ distribution of tainted milk, and the use of the contaminated ingredients and cutbacks in government food inspections.13Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2017). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stake- holder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 171-174.

Since there was no government supervision for such cases at the time, consumers were forced to rely on companies to act responsibly. Such tragedies and the financial scandals of many companies continue to erode consumer confidence in companies. Accordingly, major external social events not caused by business also affect companies. No company is spared from being affected by a crisis. However, there is an opportunity to prepare in time to deal with crises. Management decision-making processes should thus include issue management, risk management and crisis management.14Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stake- holder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 152-158.

Distinguishing between these three types of management is difficult. Many product managers cannot distinguish between “risks” and “issues,” which has led to their being referred to as the Siamese twins of public relations.

The Issue Management Council’s definitions are as follows:

- Problem: A discrepancy between an organization’s actions and stakeholder expectations.

- Risk: A potential problem that may or may not occur.

- Crisis: A problem that has escalated to a critical state.15Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2017). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stake- holder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 171-174.

The aim is to act effectively and thus enforce issue, risk and crisis management without gaps. This involves comparing the company’s situation with the expectations of its stakeholders and eliminating discrepancies.

Effective issue, risk and crisis management can enable the company to avoid a crisis as well as minimize its impact and is crucial for post-crisis management.16Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2017). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stake- holder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 171-174.

3 Practical implementation

Failing to prevent these risks can cause serious damage and so risk managers should eliminate them whenever possible. Companies have three main methods at their disposal to respond to crisis situations.

3.1 Risk management

Being able to look into the future with certainty would relieve companies and their decisionmakers of various serious decisions and protect them from potential risks. As long as the future remains volatile and unpredictable, companies must prepare for potential risks and find the right way to deal with them in order to prevent serious consequences for their own organization just in time. In order to hold one’s own position in the ever dynamic and uncertain environment, speed, flexibility and adaptability are required. Consequently, corporate success is only possible if potential risks and their effects are assessed and considered during the decision-making process. However, successful corporate management recognizes and considers not only the risks, but also the opportunities in each case.17Gleißner, W. (2017). Grundlagen des Risikomanagements: mit fundierten Informationen zu besseren Ent- scheidungen. Franz Vahlen. München. p. 32-38. To meet this challenge, companies use risk management. Risk management is understood to mean the measurement and control of all business risks throughout the company. The focus is on risks that might occur, with the aim of preventing them. To this end, specific measures are developed and implemented.18Wolke, T. (2017). Risk Management. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. Berlin. p.7-11. In general, a systematic process for risk control and risk management is referred to as risk management.19Brandstäter, J. (2013). Agile IT-Projekte erfolgreich gestalten. Risikomanagement als Ergänzung zum Scrum. Springer Vieweg. Wiesbaden. p. 22. Project planning and execution are supported by integrated risk management and its sub-processes and measures, in monitoring, controlling and managing risks. Where potential risks exist, potential opportunities can also be identified. Consequently, risk management and opportunity management can be related. Most projects of a company do not lead to success without accepting certain risks. On a day-to-day basis, risks are consciously taken in order to achieve profits. Individual sub-processes and measures of risk management are also applied in opportunity management, whereby the focus is not on risks but on potential opportunities. Consequently, a company benefits in many ways from the defined processes of risk management.20Gleißner, W. (2011). Grundlagen des Risikomanagements im Unternehmen. Controlling, Unternehmensstrate- gie und wertorientiertes Management. Vahlen. München. p. 37 f..

3.1.1 Risk management processes and methods

The design of risk management processes is usually very diverse and varied. In particular, the process steps can differ significantly in number depending on the company and industry. In general, however, four core elements are assigned to risk management:

- Risk identification

- Risk analysis and assessment

- Risk treatment

- Risk control/monitoring

The four primary processes are interrelated in a cycle and form a common ongoing and recurring risk management process. Starting with risk identification, risks that may occur are identified and determined. Various methods and tools are available to identify, analyze and finally evaluate the risks.21Wolke, T. (2016) Risikomanagement. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. Berlin, 2016). p. 1-4.

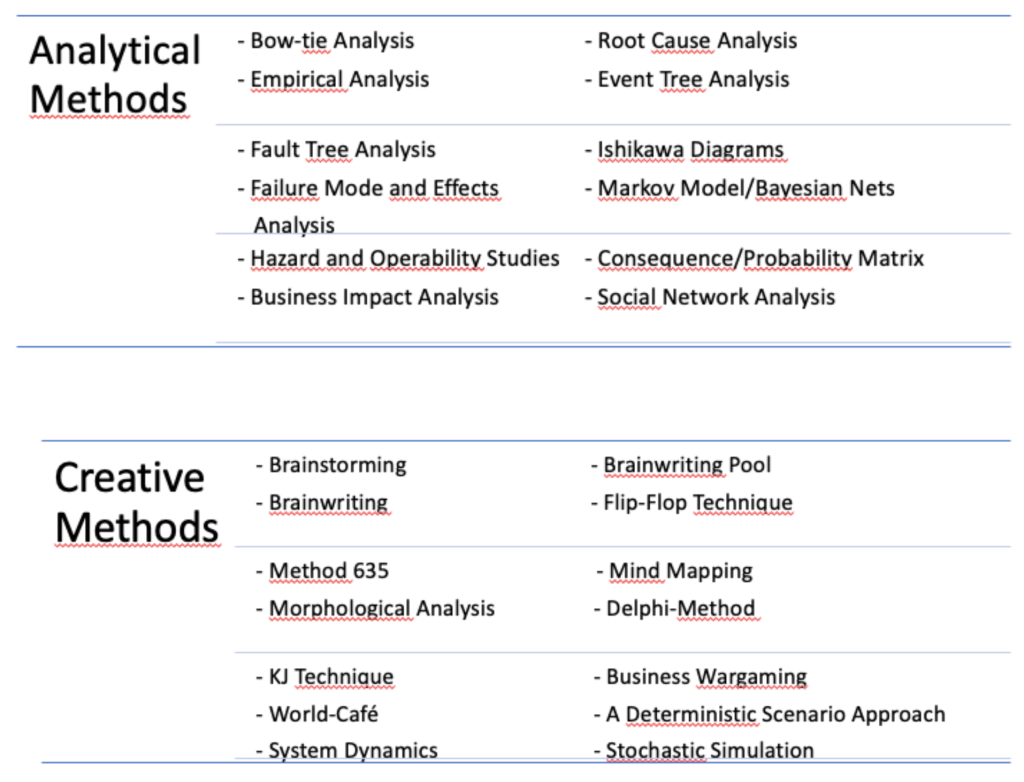

Collection methods are used when the risks are known and clearly expected. Checklists are for example often used to identify potential risks and their causes. For previously unknown risk potentials, analytical methods and creativity methods are applied. With the help of these methods, possible risks are sought with which the company has had no contact in the past, but which may occur in the future are sought.23Wolke, T. (2016) Risikomanagement. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. Berlin, 2016). p. 1-4.

Complete identification of potential risks is of great importance, as it influences the entire further course of the risk management process. After identification, the risks are analyzed and evaluated. However, the aim is also to subject the potential opportunities to analysis.25Wolke, T. (2017). Risk Management. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. Berlin. p.7-11.

After the risk analysis and assessment, different risk strategies are taken, and measures for further proceedings are developed to plan how to deal with the risks.17 Depending on their nature, the aim is to avoid, mitigate, shift or accept risks. In the fourth and thus final phase, risk control and monitoring are carried out. The risk situation is permanently monitored in each phase. The risk management measures taken are monitored and reviewed. In order to sustainably support the risk management process and ensure its success, communication is necessary in each phase. In addition, experiences and results must be continuously documented and reviewed.26Wolke, T. (2017). Risk Management. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. Berlin. p.7-11.

3.1.2 Risk management objectives and tasks

Risk management pursues the goal of promoting the security of a company’s existence and protecting the company from serious consequences. In principle, companies pursue performance-related, social and financial objectives. The objectives of risk management can be derived from general corporate objectives. The realization of corporate goals and safeguarding of the expected corporate success can only be achieved if risk management recognizes potential threats, acts preventively or in a timely manner, mitigates and eliminates them. Consequently, a company-wide risk awareness must be created, and all stakeholders must be sensitized to recognize risks. The handling and associated measures for risk management have to be kept transparent and recognizable for all those involved by working with systematic risk management.27Diederichs, M. (2012). Risikomanagement und Controlling. Franz Vahlen. München. p. 10-14.

3.1.3 Necessity of risk management

In the past and in the present, humanity has frequently been put to the test. The financial crisis of 2008, natural disasters and, in view of the current circumstances, a pandemic and a war, show how quickly dangers and risks can lead to serious and lasting crises. Supply risks, bottlenecks at companies due to delivery problems or a lack of personnel, crisis-related threats to existence are risks and consequences that not every company anticipates, but which emphasize the importance of risk management and countermeasures, and how important it is to initiate countermeasures quickly.28Wolke, T. (2016) Risikomanagement. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. Berlin, 2016). p. 1-4 The integration of a risk management system enables the permanent monitoring of risks that have already been identified and the measures that have been defined to deal with them. It also ensures a much faster response time to unexpected risks. The danger of being exposed to a crisis leads companies to deal with the topic of risk management.29Wolke, T. (2017). Risk Management. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. Berlin. p.7-11.

3.2 Issue management

Definition

The terms issue and crisis management should not be used interchangeably. One of the principles of issue management is that it seems less action-orientated and proactive. It means that it identifies the potential beforehand and before it takes a negative impact on the company. Issue Management looks into the future and identifies potential trends and risks that could influence the organization in the course of action.30Regester, M. & Larkin, J.. Risk issue and crisis management: A casebook of best practice. 3rd Edition. (GB, Clays Ltd, St. Ives plc. London. 2005) p.42

An issue is a gap between stakeholders’ expectations and how the company is operating. To fill the gap, organizations must make decisions based on debates, controversy, and opinions to resolve the matter. However, deciding does not resolve the issue.31Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. p. 158.

3.2.1 Issue management process

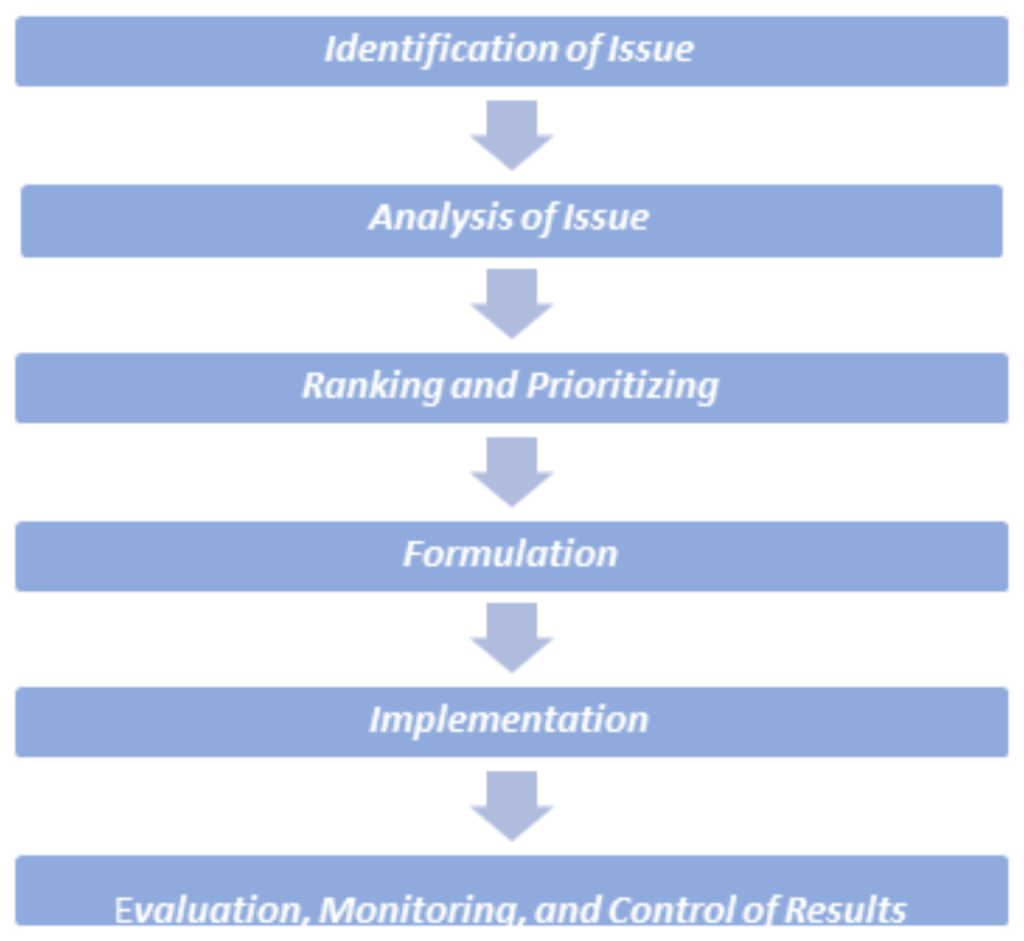

The Figure presents the most common stages in the process. It contains planning and implementation aspects. Besides, it exists many conceptualizations because of many different authorities. Those could use different steps and stages.32Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. p. 160.

Identification of Issue

The Identification of Issues is sometimes referred to in different ways, such as e.g., social forecasting, environmental scanning, and public issue scanning. Their approaches and techniques are all similar but differ in their characteristics. But each of these designations examines the environment and identifies emerging issues that may become relevant down the line or have an impact on the business or organization.

Issue Identification involves various activities:

- Scanning social media and publications to build a comprehensive inventory of issue

- Review these findings

- Summarize an internal report for the organization

- Subscribe to a trend of information services prepared by third parties e.g. specialized consulting firms34Coates et. al. 1986, p.18 in Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. p. 158.

The futurist Graham T.T. Molitor proposed five leading forces to predict social change:“

- Leading events

- Leading authorities or advocates

- Leading literature

- Leading organizations

- Leading political jurisdictions

“35Gaham Molitor, T. (1977) How to Anticipate Public Policy Changes. Vol.42.No 3, 4.

Nowadays social media makes it possible to spot emerging trends earlier and easier. Due to the opportunity to identify issues as soon as they started, it is possible to manage them early on.36Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stake- holder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 162.

Analysis of Issue

The following steps Analyses and Ranking are linked together. Issue analyses require a view that goes beyond. An analysis involves e.g, carefully studying, breaking down, and classifying which helps the management to understand the nature of the issues. This part is a significant step.

„

- Who (which stakeholders) are affected by the issue?

- Who has an interest in the Issue

- Who is in a position to exert influence on the issue?

- Who has expressed opinions on the Issue?

- Who ought to care about the Issue? “37William R. King. David, I. (1987) Cleland (eds.) Strategic Planning and Management Handbook (New York: The Conference Board) 259.

Ranking and Prioritizing

Prioritizing an issue is an important factor for organizations to determine which one to invest the most money and time. The organization first asks itself; how will the issue affect us and to what extent.38Dougall Ph.D. E (2008) Issue Management. Institut for Public Relations. (December 12. 2008) Available at: https://instituteforpr.org/issues-management/ Accessed on. September 14. 2022. Once these questions have been clarified, the issues are ranked according to their relevance. The lower-ranked issues may be removed and classified as low risk.39Brown, 33 in Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. Boston p. 164. Other possibilities for prioritization techniques could include polls, surveys, Delphi Technique, scenario building40Coates et. al, 46 in Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustain- ability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning p. 164., and Expert Teams41Heugens (2005), 488 in Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning p. 164.

Formulation and Implementation

While the analysis and ranking phase could be outsourced, the next stage formulation should be done by the company. The formulation is based on the analysis. In the process, the company can identify options to deal with the Issue and afterward implement thus. The formulation concerns not only possible methods of action but also strategic decisions, and intensity of actions. As well as comprehensive detailed planning.42I.C. Mac Millian and P.E: Jones (1984) , “Designing Organizations to Compete”, Journal of Business Strategy (Vol. 4 No. 4) p.13. Once the formulation is defined, the implementation process starts. In this process, many organizational matters are introduced, including resource and time planning.43Wernham R. Implenmentation: The Things That Matter. In King and Cleeand p. 453 in Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. Boston p. 165.

Evaluation, Monitoring, and Control of Results

This step focuses on the constant evaluations of their results and monitoring their actions. Furthermore, the stakeholder’s opinion is in form of a stakeholder audit including their engagement. The gathered information in this process might be useful for adjustments and changes. Also, Evaluation could be useful at every stage of the process.44Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 165.

3.2.2 Issue Life Circle

Issues tend to develop in a specific pattern. The Live circle process can be divided into 4 stages.

Stage 1:

In Stage 1 an issue begins to arise in the press or social media, which is enunciated by public interest and detected by a pollster. At this stage, the issue is low-key and slightly flexible.45Gottschalk E.J.Jr. (1982). Firm Hiring a New Type of Manager to Study Issues, Emerging Troubles. The Wall Street Journal. 33, 36 in Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sus- tainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. Boston p. 166.

Stage 2:

In this stage, the first interest group began to develop. Also, the media coverage starts. Firms may take notice but take no action. However, issue-orientated firms become more active in monitoring the issue and trying to shape or define it. Some firms have the potential to resolve the issue in form of effective responses or effective lobbying.

Stage 3:

National Media coverage begins to start and address the issue, followed by pollical jurisdiction. Due to studies and hearings, the federal government’s attention is generated.

Stage 4:

Regulation, Legislation, and Litigation follow.

All in all, issues are unsteady and the stages in the process can occur differently or in an iterative pattern. Some issues are resolved before they complete all stages. Otherwise, Issues vary with nature in their intensity and variety. Due to the complex interactions of all variables, the pattern is not predictable.46Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. Boston p. 166.

3.3 Crisis management

There is no doubt that crisis management has become an integral part of the strategic management of any company today, but its roots are deeply rooted in disaster and emergency management.48Coombs, W. T. (2010). Parameters for Crisis Communication. In W. T. Coombs, & S. J. Holladay, The Hand- book of Crisis Communication. P. 17-53. Wiley-Blackwell. Every organization experience crisis at some point in their existence, which makes crisis management an integral part of public relations. In business as in life, crises come in as many varieties as the common cold. There are so many types that it is impossible to list them all. There are many product-related crises ranging from outright failures such as Dell’s laptop batteries that overheated in 2006, resulting in millions of them being withdrawn from the market, asbestosis and thalidomide are examples of unanticipated side effects.49Coombs, W. T. (2014). Applied Crisis Communication and Crisis Management. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. There were certainly many other business crises like these. However, the types of crises are diverse: Economic crises (recessions, stock market crashes), criminal crises (kidnappings, acts of terrorism), personnel crises (strikes, workplace violence), reputational crises (logo tampering, slander), natural disasters (tornados, earthquakes), physical crises (product failures, supply breakdown) and information crises (cyberattacks).50Carroll, A. B., Brown, J. A., Buchholtz A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management 10th Edition, P.168-177. Cengage Learning. Boston.

Anyway, crisis management is the process of planning, decision making, dynamic adjustment, resolution, and training of staff in response to various crisis situations, with the aim of eliminating or reducing the threats and losses caused by the crisis. Crisis management can usually be divided into two main parts: anticipation and prevention management before the outbreak of a crisis and emergency aftercare management after the outbreak of a crisis.51Nittmann, M. (2021). Crisis communication: The case of the airline industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Master thesis. Hanken school of economics. Helsinki.

3.3.1 Crisis management frameworks and models

Models of crisis management provide a conceptual framework for planning, avoiding, dealing with, and recovering from crises. Crisis managers gain a better understanding of events by using a model. Steven Fink, an American management expert, proposed a life-cycle theory of crisis in his book Crisis management: Planning for the Inevitable published in 1986. The theory states that crises can be divided into four stages:

- Prodromal Crisis Stage, there are signs for emerging crisis and also the warning stage.

- Acute Crisis Stage, the crisis has actually happened.

- Chronic Crisis Stage, period of recovery: crisis event is still in people memories for period.

- Crisis Resolution Stage, the organization reach the goals of all crisis management, organization can do activities normally again.

As Fink and other crisis management models (including Alfonso Gonzalez-Herrero and Cornelius Pratt’s four-stage model developed in 1996) point out, crisis unfolds like a lifecycle. As Gonzalez-Herrero and Pratt defined their crisis management model, they see the phases as birth, growth, maturity, and decline, with issues management, planning-prevention, crisis management, and post-crisis phases paralleling these stages.52Carroll, A. B., Brown, J. A., Buchholtz A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management 10th Edition, P.168-177. Cengage Learning. Boston.

In 1994, Ian I.Mitroff proposed his Five-Stage Crisis Management Model which also follow a similar lifecycle progression:

- Crisis Signal Detection, seek to identify warning signs and take preventative measures.

- Probing and Prevention, active search and reduction of risk factors.

- Containment, crisis occurs and actions taken to limit its spread.

- Recovery, effort to return to normal operations.

- Learning, people review the crisis management effort and learn from it.53Paraskevas, A. (2013). Mitroff’s five stages of crisis management. In K. B. PenuelM. Statler, & R. Hagen (Eds.), Encyclopedia of crisis management (Vol. 1, pp. 629-632). SAGE Publications, Inc., https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781452275956.n214 Accessed 08 Sep.2022.

Although there are obvious differences in detail between the Mitroff’s model and the Fink’s model, they are essentially very similar. In general, the fundamental difference between the two models is that Mitroff’s model is more proactive, focusing on the decisions that crisis managers should make at each stage. Fink’s model is more descriptive, outlining the process of the crisis and focusing on the characteristics of each stage of the crisis.54Boudreaux, B.A. (2005). EXPLORING A MULTI-STAGE MODEL OF CRISIS MANAGEMENT: UTILITIES, HURRICANES, AND CONTINGENCY. Master Thesis. University of Florida. Florida.

3.3.2 Crisis communication theory

What is crisis communication? Crisis communication refers to a series of actions and processes to resolve a crisis and avoid a crisis by using communication as a means and resolving a crisis as an objective. A growing number of crises make it increasingly necessary to anticipate and prepare for critical situations so as not to harm stakeholders or the organization.55De Wolf, D., & Mejri, M. (2013). Crisis Communication failures: The BP Case Study. International Journal of Advances in Management and Economics, 2(2), P.48- 56. Crisis communication can reduce the impact of corporate crises and the potential exists to turn crises into opportunities or even business opportunities. Without crisis communication, a small crisis can become a big crisis, causing serious damage to the organization or even its dissolution. During a major threat to its reputation or business, crisis communication refers to the technologies, systems, and protocols that enable an organization to effectively communicate. The organization must be prepared for a variety of potential crises, such as extreme weather, crime, cyberattacks, product recalls, corporate malfeasance, and reputation crises. Crisis communication is both a science and an art, which can obtain the opportunity part of the crisis inside and reduce the dangerous component of the crisis.56Nittmann, M. (2021). Crisis communication: The case of the airline industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Master thesis. Hanken school of economics. Helsinki.

When an organization encounters a crisis event, the public and the organization’s stakeholders usually first try to explain and assess the organizational responsibility for the corporate incident, which is often misused and dramatized by the media. Thus, the issue of interpretation is critical to the organization’s response to a crisis. In this case, the organization’s management can combine Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) to understand the situation and pre-select possible response strategies to the public based on the current responsibility for the specific critical situation.57Verwer, F. (2018). Striking the right note on social media during a tragic crisis: The situational crisis communication theory applied to the case of the Germanwings Flight U9525 and its effects on audience response tone. Master Thesis. University of Twente. NB Enschede.

Crisis management is 80 percent communication, since crisis damage often arises from perception rather than from actual circumstances.58De Wolf, D., & Mejri, M. (2013). Crisis Communication failures: The BP Case Study. International Journal of Advances in Management and Economics, 2(2), p. 48-56. Effective crisis communications are a key component of virtually all crisis management plans, but they are not always successfully implemented. Lack of communication with key stakeholders has led to many companies failing to manage crises successfully.59Carroll, A. B., Brown, J. A., Buchholtz A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management 10th Edition, P.168-177. Cengage Learning. Boston. Communication that is prepared will be more effective than communication that is reactive. Here are ten crisis communication steps worth to memorize:

- Set up a crisis communication team.

- Selection of key spokespersons who will speak for the organization.

- Training spokespersons vigorously.

- Establishing information communication rules/ protocols.

- Identify and understand the company’s audience.

- Pre-exercise.

- Conduct a crisis assessment.

- Identify key messages.

- Decide how to communicate the information.

- Be prepared and get through it safely.

A successful crisis management effort is often damaged by the lack of communication with your internal stakeholders, since rumors are often started there. Additionally, since social media and outlets such as Twitter are gaining popularity as a way to report eyewitness accounts of disasters, terrorist attacks, and other social crises, it becomes increasingly important to dispel misinformation and provide localized information to assist in decision-making processes. Furthermore, having a spokesperson who can communicate uniformly is vital during crisis situations (point No.2).60Carroll, A. B., Brown, J. A., Buchholtz A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management 10th Edition, P.168-177. Cengage Learning. Boston.

4 Drivers and barriers

When it comes to managing and preventing risks, issues and crises, there are drivers and barriers that promote or prevent effective use of the methods. Drivers are potential opportunities for a securely positioned company. Barriers, on the other hand, limit insight and pose a threat.

4.1 Drivers in risk management

Risk management has long been considered an essential part of modern corporate management. Through the systematic and continuous identification of risks, dangers to the company are recognized, analyzed, and dealt with at an early stage. Drivers for the introduction of risk management include legal requirements. The legislator enforces legal requirements to create more control and transparency.61Denk, R. & Exner-Merkelt (2005). Corporate Risk Management. Unternehmensweites Risikomanagement als Führungsaufgabe. Linde. Wien. p. 16 f. For example, a risk management system anchored by law is required for stock corporations. Corresponding requirements for the integration of risk management are set out in the German Stock Corporation Act and the Corporate Control and Transparency Act.62Aktiengesetz § 91. Constant change is also increasingly influencing corporate culture and requires flexible and rapid adaptation processes. Short technology and product life cycles require new innovations and ideas in order to hold one’s own position in the market. Challenges of the increasing globalization of the economy, technological advances and economic crises influence the business world greatly.63Loock, H. & Steppeler, H. (2010). Marktorientierte Problemlösung im Innovationsmarketing. Gabler. Wiesbaden. p. 95-100.

Likewise, society is constantly changing, which means that customers’ demands on companies are also changing. Companies that fail to recognize these challenges and identify the risks at an early stage or fail to deal with them in the first place, will not be able to gain competitive advantages and achieve their corporate goals.64Loock, H. & Steppeler, H. (2010). Marktorientierte Problemlösung im Innovationsmarketing. Gabler. Wiesbaden. p. 96. External events and crises that have already occurred show the importance of integrated risk management for companies. Past events are often an impetus for protection against the risks and crises. The responsibility towards society and future generations has already been established in some companies. Nevertheless, the implementation in practice is not nearly sufficient. Many companies are satisfied with the minimum requirements and do not align their risk management in a future-oriented and therefore sustainable way. In general, there are many obstacles that turn out to be sources of failure.65Loock, H. & Steppeler, H. (2010). Marktorientierte Problemlösung im Innovationsmarketing. Gabler. Wiesbaden. p. 103-107.

4.2 Drivers in issue management

The issue development process has been said to take about 8 years to go through its stages and become an actual crisis. However, the development of technology and the advent of the Internet, mobile phones, etc. has significantly accelerated the whole process. Understanding how an issue has evolved requires an understanding of the political systems. In addition, the interests of stakeholders should be kept in mind.66Weiss, J. W. (2014). Business ethics: A stakeholder and issues management approach. Berrett-2021.Koehler Publishers.

4.3 Drivers in crisis management

A crisis team is designed to manage crisis situations in the best possible way and to return to normal operations as effectively and efficiently as possible. It is the highest instance of the crisis organization.67Bundy, J., Pfarrer, M.D., Short, C.E., Commbs W.T. (2016). Crises and Crisis Management: Integration, In- terpretation, and research development. SAGE Jornals, Vol.43, Issue 6, P.1665-1669. When a crisis occurs, there are many drivers of crisis management, such as being able to respond quickly in a crisis by establishing a professional crisis organization, including interfaces and reporting chains, ensure professional crisis communication by defining crisis communication principles and strategies depending on the situation. Only through proactive response and management of crisis communications can adverse effects on the organization during a crisis be avoided or reduced. Confidence of employees through preventive organization of aftercare for affected employees (Care), making the crisis go smoothly and to the desired end.68KPMG International, (2020). Crisis Planning, Response and Management Services. https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2020/03/crisis-planning-response-and-management-services.pdf accessed 13 Sep. 2022.

4.4 Barriers in risk management

In most companies, risk management is perceived as a formal constraint. The associated opportunities for are not seen and consequently not used. Meeting the legal requirements is perceived as a hurdle and risk management is introduced by force. Due to the strong rejection, risk management is neither used effectively nor fully integrated into the company. Many business units are not involved in the process. Rather there is a lack of communication among them, as mostly top managers deal with risk management. Accordingly, the necessary sensitization is insufficient, and does not reach all levels of the company or does not take place at all. There is often a lack of support from the executive board or top management.69Loock, H. & Steppeler, H. (2010). Marktorientierte Problemlösung im Innovationsmarketing. Gabler. Wiesbaden. p. 95-100. Viewing risk management as a necessary evil shows a lack of acceptance among employees and a lack of knowhow. Although a future without risks is unthinkable and impossible, many companies lack the willingness to deal with the issue in advance. Instead, they only react when the risk has already occurred, and a major crisis threatens the company. However, so-called risk blindness can cause great damage to companies. In addition to the lack of know-how, the company’s lack of resources is often responsible for a lack of or less effective risk management. Not all companies have to meet legal requirements, such as a stock corporation, so that neither the minimum requirement is met, nor is a risk management system created. A recommendation is made, but this places too much emphasis on voluntariness.70Hausarbeit.

4.5 Barriers in issue management

Companies often do not take the problem that arises seriously enough or underestimate the risk. On the one hand, there is criticism that looking for issues is often subject to many guidelines. After a crisis, these are often not sufficiently analyzed in how this could have been prevented and need more following research.71Weiss, J. W. (2014). Business ethics: A stakeholder and issues management approach. Berrett-2021.KoehlerPublishers.

4.6 Barriers in crisis management

Researchers found that crisis communication barriers are often responsible for challenges associated with crisis management.72Fischer, D., Posegga, O., Fischbach, K. (2016). Communication Barriers in Crisis Management: A Literature Review. European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), 24th, No.168, AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). Istanbul, Turkey. Manoj and Baker`s (2007) research73Manoj, B., and A. H. Baker (2007). “Communication challenges in emergency response.” Communications of the ACM Vol.50 (3), p. 51–53. on crisis communication defines three types of communication barriers:

- Technological barriers

- Social barriers

- Organizational barriers

A technological barrier refers to a problem associated with the technology used in crisis management. Social barriers arise as a result of differences between individuals in various crisis response organizations or the general public during times of crisis. During crisis management, organizational barriers may arise between and within organizations.

References

- 1Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 152-158.

- 2Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 152-158.

- 3Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 152-158.

- 4Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 152-158.

- 5Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stake- holder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 152-158.

- 6Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stake- holder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 152-158.

- 7Pufé, I. (2014). Nachhaltigkeit. UVK. Konstanz, München. p. 20.

- 8Pufé, I. (2014). Nachhaltigkeit. UVK. Konstanz, München. p. 34.

- 9Pufé, I. (2014). Nachhaltigkeit. UVK. Konstanz, München. p. 190.

- 10Mayer, K. (2020). Nachhaltigkeit: 125 Fragen und Antworten. Springer. Hofheim. p. 5.

- 11Mayer, K. (2020). Nachhaltigkeit: 125 Fragen und Antworten. Springer. Hofheim. p. 25-29.

- 12Mayer, K. (2020). Nachhaltigkeit: 125 Fragen und Antworten. Springer. Hofheim. p. 25-29.

- 13Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2017). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stake- holder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 171-174.

- 14Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stake- holder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 152-158.

- 15Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2017). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stake- holder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 171-174.

- 16Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2017). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stake- holder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 171-174.

- 17Gleißner, W. (2017). Grundlagen des Risikomanagements: mit fundierten Informationen zu besseren Ent- scheidungen. Franz Vahlen. München. p. 32-38.

- 18Wolke, T. (2017). Risk Management. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. Berlin. p.7-11.

- 19Brandstäter, J. (2013). Agile IT-Projekte erfolgreich gestalten. Risikomanagement als Ergänzung zum Scrum. Springer Vieweg. Wiesbaden. p. 22.

- 20Gleißner, W. (2011). Grundlagen des Risikomanagements im Unternehmen. Controlling, Unternehmensstrate- gie und wertorientiertes Management. Vahlen. München. p. 37 f..

- 21Wolke, T. (2016) Risikomanagement. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. Berlin, 2016). p. 1-4.

- 22Wolke, T. (2017). Risk Management. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. Berlin. p.7-11.

- 23Wolke, T. (2016) Risikomanagement. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. Berlin, 2016). p. 1-4.

- 24Romeike, F. & Hager, P. (2013). Erfolgsfaktor Risk Management 3.0 – Methoden, Beispiele, Checklisten: Praxishandbuch für Industrie und Handel. Springer. Wiesbaden. p.104-108.

- 25Wolke, T. (2017). Risk Management. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. Berlin. p.7-11.

- 26Wolke, T. (2017). Risk Management. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. Berlin. p.7-11.

- 27Diederichs, M. (2012). Risikomanagement und Controlling. Franz Vahlen. München. p. 10-14.

- 28Wolke, T. (2016) Risikomanagement. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. Berlin, 2016). p. 1-4

- 29Wolke, T. (2017). Risk Management. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. Berlin. p.7-11.

- 30Regester, M. & Larkin, J.. Risk issue and crisis management: A casebook of best practice. 3rd Edition. (GB, Clays Ltd, St. Ives plc. London. 2005) p.42

- 31Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. p. 158.

- 32Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. p. 160.

- 33Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. p. 161.

- 34Coates et. al. 1986, p.18 in Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. p. 158.

- 35Gaham Molitor, T. (1977) How to Anticipate Public Policy Changes. Vol.42.No 3, 4.

- 36Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stake- holder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 162.

- 37William R. King. David, I. (1987) Cleland (eds.) Strategic Planning and Management Handbook (New York: The Conference Board) 259.

- 38Dougall Ph.D. E (2008) Issue Management. Institut for Public Relations. (December 12. 2008) Available at: https://instituteforpr.org/issues-management/ Accessed on. September 14. 2022.

- 39Brown, 33 in Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. Boston p. 164.

- 40Coates et. al, 46 in Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustain- ability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning p. 164.

- 41Heugens (2005), 488 in Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning p. 164.

- 42I.C. Mac Millian and P.E: Jones (1984) , “Designing Organizations to Compete”, Journal of Business Strategy (Vol. 4 No. 4) p.13.

- 43Wernham R. Implenmentation: The Things That Matter. In King and Cleeand p. 453 in Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. Boston p. 165.

- 44Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 165.

- 45Gottschalk E.J.Jr. (1982). Firm Hiring a New Type of Manager to Study Issues, Emerging Troubles. The Wall Street Journal. 33, 36 in Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sus- tainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. Boston p. 166.

- 46Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. Boston p. 166.

- 47Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. Boston p. 166.

- 48Coombs, W. T. (2010). Parameters for Crisis Communication. In W. T. Coombs, & S. J. Holladay, The Hand- book of Crisis Communication. P. 17-53. Wiley-Blackwell.

- 49Coombs, W. T. (2014). Applied Crisis Communication and Crisis Management. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- 50Carroll, A. B., Brown, J. A., Buchholtz A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management 10th Edition, P.168-177. Cengage Learning. Boston.

- 51Nittmann, M. (2021). Crisis communication: The case of the airline industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Master thesis. Hanken school of economics. Helsinki.

- 52Carroll, A. B., Brown, J. A., Buchholtz A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management 10th Edition, P.168-177. Cengage Learning. Boston.

- 53Paraskevas, A. (2013). Mitroff’s five stages of crisis management. In K. B. PenuelM. Statler, & R. Hagen (Eds.), Encyclopedia of crisis management (Vol. 1, pp. 629-632). SAGE Publications, Inc., https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781452275956.n214 Accessed 08 Sep.2022.

- 54Boudreaux, B.A. (2005). EXPLORING A MULTI-STAGE MODEL OF CRISIS MANAGEMENT: UTILITIES, HURRICANES, AND CONTINGENCY. Master Thesis. University of Florida. Florida.

- 55De Wolf, D., & Mejri, M. (2013). Crisis Communication failures: The BP Case Study. International Journal of Advances in Management and Economics, 2(2), P.48- 56.

- 56Nittmann, M. (2021). Crisis communication: The case of the airline industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Master thesis. Hanken school of economics. Helsinki.

- 57Verwer, F. (2018). Striking the right note on social media during a tragic crisis: The situational crisis communication theory applied to the case of the Germanwings Flight U9525 and its effects on audience response tone. Master Thesis. University of Twente. NB Enschede.

- 58De Wolf, D., & Mejri, M. (2013). Crisis Communication failures: The BP Case Study. International Journal of Advances in Management and Economics, 2(2), p. 48-56.

- 59Carroll, A. B., Brown, J. A., Buchholtz A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management 10th Edition, P.168-177. Cengage Learning. Boston.

- 60Carroll, A. B., Brown, J. A., Buchholtz A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management 10th Edition, P.168-177. Cengage Learning. Boston.

- 61Denk, R. & Exner-Merkelt (2005). Corporate Risk Management. Unternehmensweites Risikomanagement als Führungsaufgabe. Linde. Wien. p. 16 f.

- 62Aktiengesetz § 91.

- 63Loock, H. & Steppeler, H. (2010). Marktorientierte Problemlösung im Innovationsmarketing. Gabler. Wiesbaden. p. 95-100.

- 64Loock, H. & Steppeler, H. (2010). Marktorientierte Problemlösung im Innovationsmarketing. Gabler. Wiesbaden. p. 96.

- 65Loock, H. & Steppeler, H. (2010). Marktorientierte Problemlösung im Innovationsmarketing. Gabler. Wiesbaden. p. 103-107.

- 66Weiss, J. W. (2014). Business ethics: A stakeholder and issues management approach. Berrett-2021.Koehler Publishers.

- 67Bundy, J., Pfarrer, M.D., Short, C.E., Commbs W.T. (2016). Crises and Crisis Management: Integration, In- terpretation, and research development. SAGE Jornals, Vol.43, Issue 6, P.1665-1669.

- 68KPMG International, (2020). Crisis Planning, Response and Management Services. https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2020/03/crisis-planning-response-and-management-services.pdf accessed 13 Sep. 2022.

- 69Loock, H. & Steppeler, H. (2010). Marktorientierte Problemlösung im Innovationsmarketing. Gabler. Wiesbaden. p. 95-100.

- 70Hausarbeit.

- 71Weiss, J. W. (2014). Business ethics: A stakeholder and issues management approach. Berrett-2021.KoehlerPublishers.

- 72Fischer, D., Posegga, O., Fischbach, K. (2016). Communication Barriers in Crisis Management: A Literature Review. European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), 24th, No.168, AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). Istanbul, Turkey.

- 73Manoj, B., and A. H. Baker (2007). “Communication challenges in emergency response.” Communications of the ACM Vol.50 (3), p. 51–53.

- 1Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 152-158.

- 2Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 152-158.

- 3Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 152-158.

- 4Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 152-158.

- 5Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stake- holder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 152-158.

- 6Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stake- holder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 152-158.

- 7Pufé, I. (2014). Nachhaltigkeit. UVK. Konstanz, München. p. 20.

- 8Pufé, I. (2014). Nachhaltigkeit. UVK. Konstanz, München. p. 34.

- 9Pufé, I. (2014). Nachhaltigkeit. UVK. Konstanz, München. p. 190.

- 10Mayer, K. (2020). Nachhaltigkeit: 125 Fragen und Antworten. Springer. Hofheim. p. 5.

- 11Mayer, K. (2020). Nachhaltigkeit: 125 Fragen und Antworten. Springer. Hofheim. p. 25-29.

- 12Mayer, K. (2020). Nachhaltigkeit: 125 Fragen und Antworten. Springer. Hofheim. p. 25-29.

- 13Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2017). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stake- holder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 171-174.

- 14Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stake- holder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 152-158.

- 15Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2017). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stake- holder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 171-174.

- 16Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2017). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stake- holder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 171-174.

- 17Gleißner, W. (2017). Grundlagen des Risikomanagements: mit fundierten Informationen zu besseren Ent- scheidungen. Franz Vahlen. München. p. 32-38.

- 18Wolke, T. (2017). Risk Management. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. Berlin. p.7-11.

- 19Brandstäter, J. (2013). Agile IT-Projekte erfolgreich gestalten. Risikomanagement als Ergänzung zum Scrum. Springer Vieweg. Wiesbaden. p. 22.

- 20Gleißner, W. (2011). Grundlagen des Risikomanagements im Unternehmen. Controlling, Unternehmensstrate- gie und wertorientiertes Management. Vahlen. München. p. 37 f..

- 21Wolke, T. (2016) Risikomanagement. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. Berlin, 2016). p. 1-4.

- 22Wolke, T. (2017). Risk Management. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. Berlin. p.7-11.

- 23Wolke, T. (2016) Risikomanagement. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. Berlin, 2016). p. 1-4.

- 24Romeike, F. & Hager, P. (2013). Erfolgsfaktor Risk Management 3.0 – Methoden, Beispiele, Checklisten: Praxishandbuch für Industrie und Handel. Springer. Wiesbaden. p.104-108.

- 25Wolke, T. (2017). Risk Management. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. Berlin. p.7-11.

- 26Wolke, T. (2017). Risk Management. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. Berlin. p.7-11.

- 27Diederichs, M. (2012). Risikomanagement und Controlling. Franz Vahlen. München. p. 10-14.

- 28Wolke, T. (2016) Risikomanagement. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. Berlin, 2016). p. 1-4

- 29Wolke, T. (2017). Risk Management. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. Berlin. p.7-11.

- 30Regester, M. & Larkin, J.. Risk issue and crisis management: A casebook of best practice. 3rd Edition. (GB, Clays Ltd, St. Ives plc. London. 2005) p.42

- 31Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. p. 158.

- 32Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. p. 160.

- 33Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. p. 161.

- 34Coates et. al. 1986, p.18 in Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. p. 158.

- 35Gaham Molitor, T. (1977) How to Anticipate Public Policy Changes. Vol.42.No 3, 4.

- 36Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stake- holder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 162.

- 37William R. King. David, I. (1987) Cleland (eds.) Strategic Planning and Management Handbook (New York: The Conference Board) 259.

- 38Dougall Ph.D. E (2008) Issue Management. Institut for Public Relations. (December 12. 2008) Available at: https://instituteforpr.org/issues-management/ Accessed on. September 14. 2022.

- 39Brown, 33 in Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. Boston p. 164.

- 40Coates et. al, 46 in Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustain- ability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning p. 164.

- 41Heugens (2005), 488 in Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning p. 164.

- 42I.C. Mac Millian and P.E: Jones (1984) , “Designing Organizations to Compete”, Journal of Business Strategy (Vol. 4 No. 4) p.13.

- 43Wernham R. Implenmentation: The Things That Matter. In King and Cleeand p. 453 in Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. Boston p. 165.

- 44Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning.Boston p. 165.

- 45Gottschalk E.J.Jr. (1982). Firm Hiring a New Type of Manager to Study Issues, Emerging Troubles. The Wall Street Journal. 33, 36 in Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sus- tainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. Boston p. 166.

- 46Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. Boston p. 166.

- 47Carroll, A. B., Brown, J., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management. Cengage Learning. Boston p. 166.

- 48Coombs, W. T. (2010). Parameters for Crisis Communication. In W. T. Coombs, & S. J. Holladay, The Hand- book of Crisis Communication. P. 17-53. Wiley-Blackwell.

- 49Coombs, W. T. (2014). Applied Crisis Communication and Crisis Management. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- 50Carroll, A. B., Brown, J. A., Buchholtz A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management 10th Edition, P.168-177. Cengage Learning. Boston.

- 51Nittmann, M. (2021). Crisis communication: The case of the airline industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Master thesis. Hanken school of economics. Helsinki.

- 52Carroll, A. B., Brown, J. A., Buchholtz A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management 10th Edition, P.168-177. Cengage Learning. Boston.

- 53Paraskevas, A. (2013). Mitroff’s five stages of crisis management. In K. B. PenuelM. Statler, & R. Hagen (Eds.), Encyclopedia of crisis management (Vol. 1, pp. 629-632). SAGE Publications, Inc., https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781452275956.n214 Accessed 08 Sep.2022.

- 54Boudreaux, B.A. (2005). EXPLORING A MULTI-STAGE MODEL OF CRISIS MANAGEMENT: UTILITIES, HURRICANES, AND CONTINGENCY. Master Thesis. University of Florida. Florida.

- 55De Wolf, D., & Mejri, M. (2013). Crisis Communication failures: The BP Case Study. International Journal of Advances in Management and Economics, 2(2), P.48- 56.

- 56Nittmann, M. (2021). Crisis communication: The case of the airline industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Master thesis. Hanken school of economics. Helsinki.

- 57Verwer, F. (2018). Striking the right note on social media during a tragic crisis: The situational crisis communication theory applied to the case of the Germanwings Flight U9525 and its effects on audience response tone. Master Thesis. University of Twente. NB Enschede.

- 58De Wolf, D., & Mejri, M. (2013). Crisis Communication failures: The BP Case Study. International Journal of Advances in Management and Economics, 2(2), p. 48-56.

- 59Carroll, A. B., Brown, J. A., Buchholtz A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management 10th Edition, P.168-177. Cengage Learning. Boston.

- 60Carroll, A. B., Brown, J. A., Buchholtz A. K. (2018). Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability & Stakeholder Management 10th Edition, P.168-177. Cengage Learning. Boston.

- 61Denk, R. & Exner-Merkelt (2005). Corporate Risk Management. Unternehmensweites Risikomanagement als Führungsaufgabe. Linde. Wien. p. 16 f.

- 62Aktiengesetz § 91.

- 63Loock, H. & Steppeler, H. (2010). Marktorientierte Problemlösung im Innovationsmarketing. Gabler. Wiesbaden. p. 95-100.

- 64Loock, H. & Steppeler, H. (2010). Marktorientierte Problemlösung im Innovationsmarketing. Gabler. Wiesbaden. p. 96.

- 65Loock, H. & Steppeler, H. (2010). Marktorientierte Problemlösung im Innovationsmarketing. Gabler. Wiesbaden. p. 103-107.

- 66Weiss, J. W. (2014). Business ethics: A stakeholder and issues management approach. Berrett-2021.Koehler Publishers.

- 67Bundy, J., Pfarrer, M.D., Short, C.E., Commbs W.T. (2016). Crises and Crisis Management: Integration, In- terpretation, and research development. SAGE Jornals, Vol.43, Issue 6, P.1665-1669.

- 68KPMG International, (2020). Crisis Planning, Response and Management Services. https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2020/03/crisis-planning-response-and-management-services.pdf accessed 13 Sep. 2022.

- 69Loock, H. & Steppeler, H. (2010). Marktorientierte Problemlösung im Innovationsmarketing. Gabler. Wiesbaden. p. 95-100.

- 70Hausarbeit.

- 71Weiss, J. W. (2014). Business ethics: A stakeholder and issues management approach. Berrett-2021.KoehlerPublishers.

- 72Fischer, D., Posegga, O., Fischbach, K. (2016). Communication Barriers in Crisis Management: A Literature Review. European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), 24th, No.168, AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). Istanbul, Turkey.

- 73Manoj, B., and A. H. Baker (2007). “Communication challenges in emergency response.” Communications of the ACM Vol.50 (3), p. 51–53.