Authors: Jessica Piszczek, Sophia Sgraja, Emmanuelle St-Pierre-Wittwer

Edited by: Tom Glaeseker, Jens Holzkämper, Luca Thost, Tammo Resener, Janine Bekel, Denise Ebel, Nele Eilers, Annalena Klauck, Nataliya Surski, Viola Czerwonka, Viktor Dmitriyev

Last updated: January 01, 2023

1 Definition

First mentioned in the 16th century, the term entered German-language business administration at the end of the 1990s.1Aulinger, A. Entrepreneurship – Selbstverständnis und Perspektiven einer Forschunsgdisziplin. (2003). After the term entrepreneur has undergone a historic development of diverse interpretations, today this idea often goes hand in hand with the Schumpeterian sense. Joseph Schumpeter defines the entrepreneur as follows:

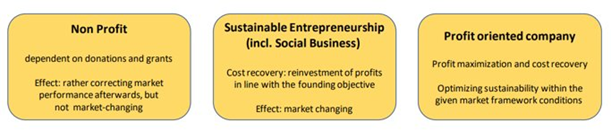

“Entrepreneur is an innovator who carries out new combinations of economic development, which are new goods, a new method of production, new markets, new sources of raw material, or new organizational form”1Aulinger, A. Entrepreneurship – Selbstverständnis und Perspektiven einer Forschunsgdisziplin. (2003), p. 5. and attributes the characteristic of innovative behavior to the latter in particular.2Aulinger, A. Entrepreneurship – Selbstverständnis und Perspektiven einer Forschunsgdisziplin. (2003). Today, entrepreneurs can be seen as catalysts in establishing value through network creation by bringing together people, money, and ideas. Sustainable entrepreneurs differ in comparison to traditional entrepreneurs in terms of addressing environmental and social problems while applying the logic of economic success. Sustainable entrepreneurship further describes the process of realizing sustainability innovations through the mass market and fulfilling the unmet demands of larger groups of stakeholders.3 Schaltegger, S. & Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 20, 222–237 (2011). Thus, a determining characteristic of sustainable entrepreneurship is that there is no primary or exclusive profit orientation. It is neither designed to be exclusively profit-oriented (e.g., a GmbH) nor exclusively for the public good (e.g., an NGO). While generating prosperity that serves not only the company but also the ecology and/or society, it is situated somewhere “in between for-profit and not-for-profit, in between cash and cause.”4 Schaltegger S. Sustainable Entrepreneurship als Treiber von Transformation. Retrieved on 24/08/2021: https://www.zukunftsinstitut.de/artikel/sustainable-entrepreneurship-als-treiber-von-transformation/ (2017).

Figure 2 illustrates the key activities of sustainable entrepreneurs. One of the most important missions of sustainable entrepreneurs is to identify opportunities for innovation, which can include gaps in the market or assumed societal needs. They also ensure that ideas are successfully implemented and create new products and services.7 Schaltegger S. Sustainable Entrepreneurship als Treiber von Transformation. Retrieved on 24/08/2021: https://www.zukunftsinstitut.de/artikel/sustainable-entrepreneurship-als-treiber-von-transformation/ (2017).

1.1 Differences in the characteristics of sustainability-oriented entrepreneurship

The conjunction between entrepreneurship and sustainable development has been addressed from various perspectives, including ecopreneurship, social entrepreneurship, sustainable entrepreneurship, and institutional entrepreneurship. Environmentally oriented entrepreneurship, or so-called “ecopreneurship,” is aimed at economic success while helping solve environmental problems (cf. Figure 3).

| Ecopreneurship | Social Entre-preneurship | Institutional Entrepreneurship | Sustainable Entrepreneurship | |

| Main goals | Earn money by solving environmental problems | Achieve societal goals by securing funding | Changing institutions | Create sustainable development through corporate activities |

| Economic goals | Aim | Mean | Mean or Aim | Mean and Aim |

Ecopreneurs are very similar to sustainable entrepreneurs as both focus on environmental aspects; however, in contrast to sustainable entrepreneurs, the value focus of ecopreneurs is not social performance. Recent developments such as the UN Global Compact have made the social impact more relevant, which implies that ecopreneurs have to more systematically integrate social aspects into their innovations. Thus, the degree to which these aspects are integrated implies that the gap toward being sustainable entrepreneurs is closed.9 Schaltegger, S. & Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 20, 222–237 (2011).

As sustainable entrepreneurs seek to create sustainable development through corporate activities, economic goals are an inherent part of achieving market success and also represent a means toward societal change. Thus, social entrepreneurship can represent a subcategory of sustainable entrepreneurship. Organizations are regarded as hybrid when they try to solve social and environmental problems through the application of market mechanisms.10 Ebrahim, A., Battilana, J. & Mair, J. The governance of social enterprises: Mission drift and accountability challenges in hybrid organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 34, 81–100 (2014). Legal forms for hybrid organizations include registered associations (e.V.), cooperatives (eG), charitable companies with limited liability (gGmbH), and benefit corporations (cf. Chapter 3.1).

Social entrepreneurship is concerned with achieving societal goals and the provision of innovation to emerging markets and developing economies by securing funding, thereby pursuing financial goals as a means to achieving societal goals. An example of social entrepreneurship is Grameen Bank from Bangladesh, which provides micro-finance to poor people. Its founder, and Nobel Prize winner Dr. Mohammad Yunus, is one of the best-known social business pioneers.

Actors who create new institutions or contribute to changes that transform institutions are called institutional entrepreneurs. As sustainable entrepreneurs sought to change market settings and institutions, the initiative to change institutional settings created links between sustainable entrepreneurship and institutional entrepreneurship.11 Schaltegger, S. & Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 20, 222–237 (2011).

1.2 Success factors of sustainable entrepreneurship

The key factor of success among sustainable start-ups has been found to be the design of the business model.12 Bocken, N. M. P., Rana, P. & Short, S. W. Value mapping for sustainable business thinking. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 32, 67–81 (2015). Four guiding principles (or minimum requirements) have been identified in the development of sustainable business models: sustainability orientation, extended value creation, systemic thinking, and stakeholder integration.13 Breuer, H., Fichter, K., Lüdeke-Freund, F. & Tiemann, I. Sustainability-oriented business model development: principles, criteria and tools. 31 (2018). Sustainability-oriented innovation and business model innovation require normative considerations.14 Breuer, H. & Lüdeke-Freund, F. Values-Based Innovation Framework – Innovating by What We Care About. (2015). Guidance for normative management decisions is given through the principles of eco-efficiency, self-sufficiency, consistency, fair distribution of wealth, and risk avoidance.15 Fichter, K. Interpreneurship: Nachhaltigkeitsinnovationen in interaktiven Perspektiven eines vernetzenden Unternehmertums. (Metropolis-Verl, Marburg, 2005).

The principle of extended value creation demands the extension of value creation beyond the usual groups of stakeholders, such as customers and shareholders, by integrating market and non-market actors in both monetary and non-monetary considerations.16 Breuer, H. & Lüdeke-Freund, F. Values-Based Innovation Management – Innovating by What We Care About. (Palgrave, London, 2017). The extension of sustainability integration into corporate activities requires the simultaneous achievement of economic, social, and environmental value by corporations. However, this is characterized by a high degree of complexity and uncertainty due to various and oftentimes conflicting objectives.17 Muñoz, P. & Cohen, B. Sustainable Entrepreneurship Research: Taking Stock and looking ahead: Sustainable Entrepreneurship Research. Bus. Strategy Environ. 27, 300–322 (2018). It also raises the challenge of first defining and negotiating priorities and then ascertaining the directions among multiple goals18 Breuer, H., Fichter, K., Lüdeke-Freund, F. & Tiemann, I. Sustainability-oriented business model development: principles, criteria and tools. 31 (2018). (cf. Chapter 4.2). The principle of system thinking places specific emphasis on interaction and bidirectional relations between a company’s internal and external perspectives, with a focus on the firm’s impact. Relatedly, the first two principles require a more systematic approach to management, for example, through a reflection of the actual sustainable value generated through the new business model.19 Breuer, H., Fichter, K., Lüdeke-Freund, F. & Tiemann, I. Sustainability-oriented business model development: principles, criteria and tools. 31 (2018).

As mentioned earlier, the integration of various and potentially conflicting interests from both inside and outside the organization is essential to the development of a sustainable business model. According to stakeholder theory, the sustainability of any cooperation is defined by the extent to which it considers stakeholder interests. Stakeholders are defined as “any group or individual who can affect, or is affected by, the achievement of a corporation’s purpose.”20 Freeman, R. E. Strategic Management: A Stakehlder Approach. (Pitman, Boston, 1984). By affecting the decisions of stakeholders and shareholders, the emergence of new sustainable business models has been found to play an important role in changing the currently unsustainable socio-technical system.21 Bidmon, C. M. & Knab, S. F. The three roles of business models in societal transitions: New linkages between business model and transition research. J. Clean. Prod. 178, 903–916 (2018). By integrating the stakeholder perspective, competitive advantage is created, pressuring other companies to consider aspects of sustainability within their business model and influencing societal welfare. A practical example would be the Tesla-led pressure on the automotive sector created by the rise of electric vehicles.

| CASE STUDY: SUSTAINABLE ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN GERMANY Germany’s economy thrives on intellectual resources, with less emphasis placed on raw materials. Given this background, an active start-up culture is highly relevant. Start-ups, especially sustainability-oriented start-up companies, are regarded as drivers of innovation as they not only initiate new technologies but also increase the competitive pressure on established companies.22 Lechler, S. Entrepreneurship Education und Nachhaltigkeit. in CSR und Institutionen (ed. Genders, S.) 231–241 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2020). The topic of sustainability is playing an increasingly important role among German start-ups. For the third year in a row, more start-ups have dedicated their products and services to the green economy or social entrepreneurship. According to a survey by the German Startup Monitor, in 2018, ecological sustainability was a high priority area for 33% of companies; by 2020, the figure was already 43%.23 Kollmann, T., Jung, P. B., Kleine-Stegemann, L., Ataee, J. & de Cruppe, K. Deutscher Startup Monitor. (2020). According to a YouGov survey in Germany, more than half of all 16–25-year-olds would like to start their own business, but only six percent actually do so.20 The explanations regarding why young people were prevented from starting a business included financial insecurity for around half of the respondents, a fear of failure (44%), and a lack of financial support (44%). Thirty-seven percent of them also stated that they did not have a good business idea and did not have entrepreneurial skills (cf. Chapter 4.2). |

2 Sustainability impact of sustainable entrepreneurship

2.1 Impact of sustainable entrepreneurship on the market and society

Entrepreneurs (traditional) are strongly related to environmental damage as market failures has fueled unsustainable entrepreneurial activities. However, these market failures simultaneously create opportunities for sustainable entrepreneurs to gain economic rents while improving social and environmental conditions.24 Cohen, B. & Winn, M. I. Market imperfections, opportunity and sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 22, 29–49 (2007).25 Dean, T. J. & McMullen, J. S. Toward a theory of sustainable entrepreneurship: Reducing environmental degradation through entrepreneurial action. J. Bus. Ventur. 22, 50–76 (2007).26 Schaltegger, S., Lüdeke-Freund, F. & Hansen, E. G. Business Models for Sustainability: A Co-Evolutionary Analysis of Sustainable Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Transformation. Organ. Environ. 29, 264–289 (2016). Entrepreneurial actions can resolve environmental challenges by exploiting profitable opportunities from environmentally relevant market failures. For example, the market failure of imperfect information, where knowledge is incomplete, can create opportunities for addressing producer and consumer realms. Regarding the producer realm, the development of environmentally friendly production processes or products can present cost savings and create a competitive advantage. In terms of the customer sphere, with information that enhances customers’ knowledge of product attributes, such as methods of production, product contents, product use, and post-consumer disposal, customers can create advantages for environmentally superior producers27 Schaltegger, S. & Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 20, 222–237 (2011). (cf. Chapter 4.1).

Some of the innovations of sustainable entrepreneurs might have little chance of success under inconvenient market conditions; as such, these entrepreneurs must consider market factors while seeking to influence market conditions.28 Schaltegger, S. & Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 20, 222–237 (2011). Therefore, sustainable entrepreneurship is considered an essential driver of the sustainability transition21 and the transformation of the economic system toward a more socially and ecologically sustainable system.29 Cohen, B. & Winn, M. I. Market imperfections, opportunity and sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 22, 29–49 (2007). 30 Hockerts, K. & Wüstenhagen, R. Greening Goliaths versus emerging Davids — Theorizing about the role of incumbents and new entrants in sustainable entrepreneurship. Sustain. Dev. Entrep. 25, 481–492 (2010).31 Pacheco, D., Dean, T. & Payne, D. Escaping the Green Prison: Entrepreneurship and the Creation of Opportunities for Sustainable Development. J. Bus. Ventur. 25, 464–480 (2010). For example, the aim of the green economy is to combine prosperity, environmental sustainability, and social justice. It builds on the belief that destroying the natural foundations of economic activity cannot create lasting prosperity. From an ecological point of view, the aim is to comply with the framework of natural ecosystems and available resources by creating a low-pollution, climate-neutral, and resource-efficient (circular) economy. The sustainability transition can be impacted by engaging in the improvement of sustainability performance and increasing the market share of sustainability-oriented products and services.32 Barbier, E. B. A New Blueprint for a Green Economy. (Routledge, London, 2013).

Theoretically, large corporations are best placed to reduce negative externalities, even though, in practice, the organizational structure and economic profitability of (unsustainable) business models prevent disruptive innovations for purposes of sustainability. Therefore, it has been suggested that new ventures are more likely to cause the necessary disruptive innovations as they lack the barrier of inflexible structures from large organizations. The sustainability transition can be impacted by engaging in the improvement of sustainability performance and increasing the market share of sustainability-oriented products and services.33 Hockerts, K. & Wüstenhagen, R. Greening Goliaths versus emerging Davids — Theorizing about the role of incumbents and new entrants in sustainable entrepreneurship. Sustain. Dev. Entrep. 25, 481–492 (2010). The European Union also accounts for this and, therefore, financially supports new enterprises (cf. Chapter 4.1) that address pressing social and environmental issues.34 Bocken, N. M. P., Rana, P. & Short, S. W. Value mapping for sustainable business thinking. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 32, 67–81 (2015).

2.2 Challenges in measuring sustainability in new ventures

The common ground between traditional entrepreneurship and sustainability is the concept of longevity. Key in this context is the focus on securing long-lasting goods, values, or services aimed at preserving current resources for the needs of future generation (sustainability) and developing unique solutions for the long term (entrepreneurship).35 Greco, A. & de Jong, G. SUSTAINABLE ENTREPRENEURSHIP: DEFINITIONS, THEMES, AND RESEARCH GAPS. (2017). The concept is consistent with the Brundtland Report’s definition of sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”36 Brundtland Commission. Our Common Future. (1987). The concept of intergenerational equity has been criticized for being difficult in practice37 Horne, J. The sustainability impact of new ventures : measuring and managing entrepreneurial contributions to sustainable development. 189 (2019). as the needs of future generations can hardly be anticipated due to the increasing rate of change. There has been the suggestion that the aim of sustainable entrepreneurship goes beyond the concept of longevity and consists of creating a positive impact.38 Greco, A. & de Jong, G. SUSTAINABLE ENTREPRENEURSHIP: DEFINITIONS, THEMES, AND RESEARCH GAPS. (2017). Therefore, in order to transparently showcase a corporation’s business model, net benefits on sustainable development measurements have to be made on the impact level. Measurements on the impact level are best explained as positive and negative effects on stakeholders linked directly to an organization, such as the provision of renewable energy that would not be possible without particular photovoltaic provisions.39 European Commission. Proposed approaches to social impact measurement in European Commission legislation and in practice relating to EuSEFs and the EaSI: GECES sub group on impact measurement 2014. (Publications Office, Luxemburg, 2014).

As mentioned earlier, entrepreneurs represent a promising lever toward increasing sustainability. Thus, measurements are an important part of quantifying the contributions of sustainable entrepreneurs to sustainable development. In particular, in the context of new ventures, there are four main problems regarding sustainability measurements: the rapidly changing environment of entrepreneurs, financial limitations, human capital constraints, and insufficient data management systems.40 Dichter, S., Adams, T. & Ebrahim, A. The Power of Lean Data. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 14 (2016). In an attempt to solve these problem, there have been various discussions among academics and practitioners around impact measurements, though no specific standard has evolved. Nevertheless, there is a lack of understanding concerning whether, how, and extent to which new ventures will actually lead to impact across policymakers, investors, and researchers.4 Thus, insufficient measurement schemes delay entrepreneurs as they cannot establish transparency and accountability, engage with investors, and manage stakeholders.41 Horne, J. The sustainability impact of new ventures : measuring and managing entrepreneurial contributions to sustainable development. 189 (2019).

In order to provide some level of certainty to entrepreneurs and investors concerning the potential of sustainability, a questionnaire for start-ups was developed for the project “GreenUpInvest” and is available in German.

2.3 Recent developments in impact measurements for new ventures

There are multiple institutions conducting research on sustainable entrepreneurship, such as the Centre for Entrepreneurship at the Technical University Berlin and the Borderstep Institute. Representatives of these institutions were surveyed for a doctoral thesis42 Horne, J. The sustainability impact of new ventures : measuring and managing entrepreneurial contributions to sustainable development. 189 (2019). concerned with the question of how the sustainability of new ventures could be practically measured and forecasted. The existing tool for stakeholder theory-based social return on investment (SROI) was identified in practice as satisfying most of the requirements for new ventures and was used as a starting point. SROI is a method that adds socio-economic and environmental value to the classical financial evaluation approach of return on investment (ROI). Thus, the firm’s performance and associated positive and negative effects can be evaluated.43 Reichelt, D. SROI: Social return on investment ; Modellversuch zur Berechnung des gesellschaftlichen Mehrwertes. (Diplomica Verlag, Hamburg, 2009). These requirements consist of 1) the necessity to measure the impact level, 2) the necessity to measure all three dimensions of sustainability that are due to frequent trade-offs, 3) forecasting the impact in order to counterbalance the lack of existing historical information, 4) internal and external benchmarking in order to create the greatest value for entrepreneurs and their stakeholders, and 5) low effort in order to remain practical with limited time and resources. Requirements 1–4 have been met though high resource requirements as impact measurements do not satisfy goal number five, that is, low effort. To make SROI more practicable and iterative, elements from the lean impact measurements (LIMs) are integrated to counterbalance the unfulfilled requirement from SROI measurements in new ventures. LIMs consist of six steps that can be categorized into impact identification and impact substantiation. Thus, the approach becomes sufficiently practical for application in effectual new ventures to create transparency concerning their sustainability impact.44 Horne, J. The sustainability impact of new ventures : measuring and managing entrepreneurial contributions to sustainable development. 189 (2019).

From a theoretical perspective, there have been further implications for future research, such as the argument that in the context of business model innovation and stakeholder theory, new ventures should not focus on stakeholders with the most power, legitimacy, or urgency of interest45 Parent, M. & Deephouse, D. A Case Study of Stakeholder Identification and Prioritization by Managers. J. Bus. Ethics 75, 1–23 (2007). but, rather, those that can create the greatest difference in comparison to previous alternatives. LIM has been proposed for use in identifying these stakeholders.46 Horne, J. The sustainability impact of new ventures : measuring and managing entrepreneurial contributions to sustainable development. 189 (2019).

The website start-up impact benchmark provides information about the ongoing research project of the author as well as those of fellow researchers from the Centre of Entrepreneurship and the MIT Sloan Sustainability Initiative. The website was created to publicly share the developed tools and serves as a knowledge platform for stakeholders.

3 Practical implementation

3.1 Legal forms and certifications

In 2019, there were a total of around 3.1 million legal entities (companies) in Germany. Around 61% of them were sole proprietorships, about 11.5% were organized as partnerships, 21% were corporations, and 6.5% comprised other legal forms.47 Statista. Rechtliche Einheiten/ Unternehmen nach Rechtsform und Anzahl der Beschäftigten 2019. (2021). Retrieved on 30/08/2021: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/237346/umfrage/unternehmen-in-deutschland-nach-rechtsform-und-anzahl-der-beschaeftigten The implementation of an entrepreneur’s business idea and the success of the enterprise are primary concerns when founding a company. Legal aspects are often treated with secondary importance in the founding process of a new company. However, the legal framework plays a central role, and choosing a suitable legal form is crucial for every new start-up company, especially in the long term.48 Pott, O. & Pott, A. Entrepreneurship: Unternehmensgründung, Businessplan und Finanzierung, Rechtsformen und gewerblicher Rechtsschutz. (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2015]. Sustainable enterprises offer an alternative to traditional legal organizational structures, such as limited liability companies or stock companies. Particularly relating to sustainably oriented companies, the choice of a suitable legal form can provide a framework for achieving sustainability goals, for example, through the possibility of profit investment, employee participation, or decision-making processes.

Registered Association

Registered associations are characterized by the fact that they are non-economic, non-profit associations. They are legal entities and have full legal capacity, which means that they can be bearers of rights and duties. Decision-making in registered associations is organized by equal voting rights for all members. Unlike many other legal forms, there are no annual accounts or audits. To exemplify, the Jugend Aktion Natur- und Umweltschutz Niedersachsen e. V. (JANUN) can be presented here. JANUN is a nationwide network that links youth associations, youth environmental offices, project workshops, and independent groups involved in nature conservation and environmental protection in Lower Saxony.

Cooperative

Cooperatives are a special form of economic association. Their purpose is to promote the commercial activities of members, or social or cultural interests, through joint business operations. All members have equal voting rights. One example of a registered cooperative is Bürgerwerke, which is a green electricity provider. They are the largest association of energy cooperatives in Germany, and together, they have set themselves the goal of supplying their members and citizens across Germany with electricity from the region as well as BürgerÖkogas. In this way, the citizens themselves benefit from the proceeds, participate democratically in decisions about new plants, and take part in energy transition.

Charitable company with limited liability (gGmbH)

The central difference between a company with limited liability (GmbH) and a charitable company with limited liability (gGmbH) is that the gGmbH uses its profits for charitable purposes. The focus is not on profit maximization but on non-profit outcomes. In addition, profits may not be distributed to shareholders. In fiscal terms, gGmbHs benefit as they are exempt from income and trade tax obligations. For shareholders, voting rights are generally measured according to the amount of their shareholding in the company. The non-profit character is expressed in many areas, such as staff or working procedures. An example of a gGmbH is the IT refurbisher AfB. The company’s core business is the reprocessing and resale of used IT products, such as laptops or smartphones. This approach saves resources and increases the recycling rate. In addition, the company makes an important contribution to inclusion as 43% of its employees are handicapped.

Benefit corporation

Benefit corporations represent a corporate legal form introduced in many US states since 2010. A benefit corporation is “legally a for-profit, socially obligated business, with all of the traditional corporate characteristics but with explicitly stated societal responsibilities.”49 Hiller, J. S. The Benefit Corporation and Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 118, 287–301 (2013). Although these corporations are treated like conventional companies in terms of taxation, they differ in terms of business objectives. These companies voluntarily and formally choose to make a commitment to public benefit by following the major provisions of purpose, accountability, and transparency.50 Cetindamar, D. Designed by law: Purpose, accountability, and transparency at benefit corporations. Cogent Bus. Manag. 5, 1423787 (2018). Importantly, as a legal form, benefit corporations are not to be confused with the “B Corporation” certification, which is conducted by the private B Lab Foundation.

B Corporation

B Corporations are not a legal form but a certification for sustainable enterprises. These certifications are carried out by the non-profit organization B Lab, which was founded in the USA in 2006. Certified B Corporations are committed to the highest standards in various fields such as verified social and environmental performance, public transparency, and legal accountability. In this way, profit and purpose are harmonized. Currently, more than 4,000 companies in 77 countries are B Corporation certified. Companies that have committed to added social value and ecological sustainability within the B Corporation framework include the coffee provider Coffee Circle, the drinking bottle manufacturer soulproducts, and the search engine provider Ecosia. (For further information, visit the B Corporation website where companies’ performance can be assessed against that of others).

3.2 Tools

There are a range of tools that can be used in the context of developing sustainable business models. Examples include the Sustainable Business Model Canvas and the Value Mapping Tool.

3.2.1 Sustainable Business Canvas

The Business Model Canvas was originally developed by Osterwalder and Pigneur.51 Osterwalder, A. & Pigneur, Y. Business model generation: A handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers. (Wiley&Sons, New York, 2013). This widely known tool for start-up management is used to visualize business models in a clearly structured way in order to analyze them. As part of the world’s first national start-up initiative for the green economy (StartUp4Climate initiative), this classic tool was expanded to include the dimension of sustainability, resulting in the Sustainable Business Model Canvas.52 Fichter, K. & Tiemann, I. Das Konzept ‘Sustainable Business Canvas’ zur Unterstützung nachhaltigkeitsorientierter Geschäftsmodellentwicklung. (2015).

The Sustainable Business Model Canvas serves as a template for presenting business models and is organized into nine building blocks. In contrast to the classic model, the building blocks of vision and mission, competitors, and relevant stakeholders were added to the Sustainable Business Model. Customer relationships, customer segments, and sales and communication channels were grouped into the customer building block. This resulted in the following ten building blocks: vision & mission (1), value proposition (2), customers (3), competitors (4), other relevant stakeholders (5), revenue model (6), key activities (7), key resources (8), key partnerships (9), and cost structure (cf. Figure 3).

The vision describes what will distinguish the business model in the future and what long-term goal is being pursued through the business model. 1) The business model mission depicts the central values of the business model. 2) The value proposition is considered a key element describing the value proposition (product or service) and the specific problems it can solve for customers. 3) In the area of customers, it is important to analyze (key) customers and explore the significance of sustainability for this target group. 4 and 5) The two new fields of competitors and relevant stakeholders provide a holistic view of internal and external stakeholders. 6) Within the area of the revenue model, the focus is on pricing model design and revenue source identification. 7) It also highlights the key activities required to realize the company’s value proposition and the role that sustainability plays in this process. 8) Key resources include questions about the extent to which environmentally critical factors of production are key resources. 9) Furthermore, the question of which partners are necessary for compliance with sustainability requirements plays a role in the decision on the right key partners. 10) Finally, the cost structure section is about showing which costs result from key activities/resources and whether costs can be reduced through resource-based savings.38 Further information on developing business models with the Sustainable Business Canvas can be found in this manual for conducting workshops.53 Irina Tiemann & Klaus Fichter. Developing business models with the sustainable business canvas: manual for conducting workshops. (Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg, Oldenburg, 2016).

3.2.2 Value Mapping Tool

The Value Mapping Tool is a framework that helps companies create balanced social, environmental, and economic value by integrating sustainability more deeply into their core operations and creating sustainable value propositions in response. In the context of sustainable business modeling, the tool can be used to identify three types of value (value captured, missed/destroyed or wasted, and opportunity) and four stakeholder groups (environment, society, customer, and network actors) (cf. Figure 4). It contributes to a better understanding of positive and negative value propositions for all relevant stakeholders in the value network and, thus, captures a view of value from the perspective of multiple stakeholders. Furthermore, it introduces a new way of conceptualizing value that considers wasted value in addition to the current value proposition.54 Bocken, N., Short, S., Rana, P. & Evans, S. A value mapping tool for sustainable business modelling. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 13, 482–497 (2013).

The process of value mapping comprises four major steps. The first step involves discussing the purpose of the company, that is, determining why the company exists as well as its product and/or service offerings. The second stage is to look at what value is being created for the various stakeholders, that is, both positive and negative values. The third step is to analyze missed opportunities in terms of the company creating value (e.g., capacities or capabilities) and the areas in which value is being destroyed. It also looks at the negative consequences for stakeholders. Finally, in the fourth phase, suitable strategies are sought to transform negative values into positive values. In addition, the aim is to identify further potential for improvement.55 Bocken, N. M. P., Rana, P. & Short, S. W. Value mapping for sustainable business thinking. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 32, 67–81 (2015). Although the Value Mapping Tool is suitable for qualitative assessment and has been mainly used for initial assessments of value, it is less suitable for in-depth analyses.56 Bocken, N. M. P., Rana, P. & Short, S. W. Value mapping for sustainable business thinking. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 32, 67–81 (2015).

4 Drivers and barriers

Various factors drive or inhibit the creation of sustainable enterprises. Drivers and barriers can have an impact on all three dimensions of sustainability (the social, ecological, or economic), and in the context of sustainable entrepreneurship, both drivers and barriers can be external and internal in nature. Internal factors arise from the company itself or from the founder’s inner convictions, including inner attitudes with regard to sustainability or the desire for self-employment. Factors resulting from the corporate environment are external in nature, including public acceptance and rejection or the market situation.57 Greco, A. & de Jong, G. SUSTAINABLE ENTREPRENEURSHIP: DEFINITIONS, THEMES, AND RESEARCH GAPS. (2017).

4.1 Drivers

Drivers are factors that favor sustainable entrepreneurship and, thus, engage the foundation of a new business.58 Greco, A. & de Jong, G. SUSTAINABLE ENTREPRENEURSHIP: DEFINITIONS, THEMES, AND RESEARCH GAPS. (2017). Important internal drivers are the personal character traits and attitude of the founder. Many sustainable entrepreneurs have the desire to do something good and actively contribute to sustainable development or even aim to change the world.59 Schlange, L. “WHAT DRIVES SUSTAINABLE ENTREPRENEURS?“. App. Bus. and Ent. Int., 35-45 (2006). Sustainable entrepreneurs are characterized by certain ethics and convictions that are attached to the person themselves.60 Jahanshahi, A. A. & Brem, A. Sustainability in SMEs: Top Management Teams Behavioral Integration as Source of Innovativeness. Sustainability 9, 1899 (2017). These beliefs and values lead to actions and decision-making processes characterized by sustainability.61 Kirkwood, J. & Walton, S. What motivates ecopreneurs to start businesses? Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 16, 204–228 (2010). The internal conviction and attitude toward sustainability issues can therefore be relevant internal drivers.62 Greco, A. & de Jong, G. SUSTAINABLE ENTREPRENEURSHIP: DEFINITIONS, THEMES, AND RESEARCH GAPS. (2017). Another aspect is the entrepreneurial vision, often consisting of creating something that does not yet exist but involves the ambitious goal of sustainability rather than simply generating profits. Central explanatory characteristics that boost or inhibit sustainable entrepreneurs include knowledge, skills, self-efficacy, motivation and intention, values, and attitudes.63 Schlange, L. “WHAT DRIVES SUSTAINABLE ENTREPRENEURS?“. App. Bus. and Ent. Int., 35-45 (2006).

One approach to positively influencing the development of entrepreneurial activities (i.e., an internal driver) is subsumed under the concept of entrepreneurship education, which has developed into a discourse about social entrepreneurship education. The term entrepreneurship education refers to the development of one’s own ideas and acquiring the skills to put these ideas into practice. This is accompanied by educational measures that promote entrepreneurial attitudes and skills and develop personal qualifications, values, and attitudes. (Further information can be found on the website of the Federal Austrian Ministry of Education.)

A best-practice example of a company that came into being due to the inner conviction of the founders and the aim to create something innovative is betterplace.org, Germany’s largest donation platform. The company was established as a response to the following question: “How can we use the Internet to improve the lives of people in need around the world?” The company founded a platform that is financed as a “social enterprise” through cooperation, and therefore, no money was intended, as aid projects will flow into other areas.

Closely related to the personal aspects and interacting are cultural influences, which themselves constitute an internal driver but can also be a barrier. Organizational cultures are a set of values and norms that influence ways of thinking.64 Steiber, A. & Alänge, S. The Silicon Valley Model: Management for Entrepreneurship. (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2015). To exemplify, a Malaysian study analyzed the relationship of socio-cultural factors in relation to sustainable entrepreneurship among SMEs. It identified three factors that significantly influenced the intention toward sustainable entrepreneurship: time orientation, sustainability orientation, and social norm. Thus, socio-cultural factors also influence the establishment of sustainable enterprises.65 Koe, W.-L., Omar, R. & Majid, I. A. Factors Associated with Propensity for Sustainable Entrepreneurship. Procedia – Soc. Behav. Sci. 130, 65–74 (2014).

Rapidly changing environmental conditions represent a catalyst that companies must respond to with urgency. In 1970, an international team of researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology began a study of global economic growth and published their results as a non-technical report called “The Limits to Growth.” It explained that current rates of economic and population growth are unlikely to be sustained much beyond the year 2100.66 The Limits to growth: a report for the Club of Rome’s project on the predicament of mankind. (Universe Books, New York, 1972). Even though these results were concluded 50 years ago, their allusions to the impact of climate change are more relevant today than ever before. As a result, companies need to adapt to the reality of dwindling resources and develop alternative business models—a challenge essentially serving as a driver for sustainable business.

This is also made clear by the 2030 Agenda. In 2015, the United Nations responded to the lack of sustainability. They declared 17 goals to make the world more sustainable in the future. As a result, companies need to adapt to the reality of dwindling resources and develop alternative business models-a challenge essentially serving as a driver for sustainable business.67Herlyn, E. & Lévy-Tödter, M. Die Agenda 2030 als Magisches Vieleck der Nachhaltigkeit. (Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH, 2020).

The circular economy, with its opportunities to make production and consumption more sustainable, is exactly this type of model. In this context, 4 strategies can be mentioned. Firstly, repair, maintenance and upgrade of products. This leads to longer usability, which reduces the need to buy a new product. Second, the reuse and reoperation. In this case, used products are returned to service providers and resold after testing and if needed minor repairs, which leads to new value creation. Another strategy is remanufacturing and refurbishment. When using remanufacturing, used or defective products are returned to the manufacturers. These are then disassembled and reassembled. Technological upgrades can make the new product better than the original. By refurbishment, the product is not completely disassembled. Rather, repairs are made and the product is reconditioned. The final strategy is recycling. Materials can be used for the same or a different purpose. A distinction can be made between downcycling and upcycling. Downcycling reduces the material use and the quality of the product. Upcycling requires a change in the product design. This ensures the material quality over a longer period of time and leads to new added value and cost advantages.mfn]Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH, 2020).[/mfn (Circular Economy Initiative Deutschland. Zirkuläre Geschäftsmodelle: Barrieren überwinden, Potenziale freisetzen. (2021).[/mfn]

Societal factors are an important external influence on sustainable entrepreneurship. An important development with a positive influence on sustainable entrepreneurship is the general rethinking taking place in society. According to Deloitte, in 2021, sustainability was an important topic for many consumers, with 32% interested in living a more sustainable lifestyle, and 28% of producers do not buy certain products or brands at all due to ecological or ethical concerns. Heightened customer concerns about the sustainability aspects of a product have led to a higher demand for sustainable products. People who live a sustainable lifestyle and attach great importance to aspects of health, the environment, and social issues are also called LOHAS (lifestyle of health and sustainability) and account for around one-third of the population of Western countries. LOHAS can be understood as a social trend or a change in society; in their consumption decisions, they are largely guided by aspects of sustainability and want to minimally endanger future generations through their consumption or consume as few resources as possible. Due to their lifestyle of permanently striving for sustainably oriented consumption, LOHAS represent a major sales market for sustainable entrepreneurs and, therefore, constitute a driver for sustainable entrepreneurs.68 Köhn-Ladenburger, C. Marketing für LOHAS: Kommunikationskonzepte für anspruchsvolle Kunden. (Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden, 2013). The use of sustainability labeling can also be implemented as a driver for sustainable entrepreneurship. Sustainability labels are used to show consumers the ecological attributes of products, distinguish them from conventional products, and save customers in their search for information,69 Enders, B. & Weber, T. Nachhaltiges Konsumentenverhalten – Welche Nachhaltigkeitssiegel beeinflussen den Verbraucher? in CSR und Marketing (eds. Stehr, C. & Struve, F.) 197–213 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2017). thereby creating greater transparency. A steadily growing flood of seals accompanied by frequent multiple labeling creates customer uncertainty and contradicts the actual intention of sustainability seals. Nevertheless, there are some established international third-party and state-controlled symbols that can be used to generate trust in product quality and sustainability benefits.

Furthermore, there are a number of external drivers that can be attributed to the political field. Political actors can influence through the actions of founders. For example, economic incentives are fundamental to sustainable founders and can include concessionary taxes, fees, deductions, deposits, or even subsidies. Legal instruments can also be relevant to founders, such as laws and regulations.70 Pinkse, J. & Groot, K. Sustainable Entrepreneurship and Corporate Political Activity: Overcoming Market Barriers in the Clean Energy Sector. Entrep. Theory Pract. 39, 633–654 (2015).

Financial factors are highly relevant for the survival of new business and can be a major challenge (for more information, see section on barriers). Therefore, it can be an important incentive for companies to receive monetary benefits for sustainable value. For example, the European Union provides funding for sustainable entrepreneurship, and the EU program Life considers projects based on concepts of a resource efficient, low CO2 emissions, and climate-resistant economy.

Another important field to consider is knowledge. As many founders lack the experience and know-how needed to start a business and run it successfully, political support can be an important driver. A best-practice example of political support is the start-up platform of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy. The founders received support to get started and for planning, founding, and financing, including assistance in finding financing partners. Lack of experience can also be overcome by support through training in, for example, the German platform Existenzgründer, which contains a wide range of information and support services for those considering starting a business.

Furthermore, there are aspects that can be attributed to the institutional field, which can be both drivers and barriers to the institutional embedding of sustainability. Intangible or “hard” institutions include laws, regulations, and instructions. Material or “soft” institutions include aspects such as routines and habits.71 Greco, A. & de Jong, G. SUSTAINABLE ENTREPRENEURSHIP: DEFINITIONS, THEMES, AND RESEARCH GAPS. (2017). Sustainable enterprises can trigger positive effects by changing institutions.72 Pacheco, D., Dean, T. & Payne, D. Escaping the Green Prison: Entrepreneurship and the Creation of Opportunities for Sustainable Development. J. Bus. Ventur. 25, 464–480 (2010). However, there are often conflicting interests in the form of dilemmas between individual and collective benefits in many individual and group decisions regarding environmental sustainability, which are evolutionarily stable and, therefore, difficult to change within the boundaries of the game (institutions).73 Greco, A. & de Jong, G. SUSTAINABLE ENTREPRENEURSHIP: DEFINITIONS, THEMES, AND RESEARCH GAPS. (2017).

4.2 Barriers

Barriers can be defined as factors that discourage potential company founders from starting a company. When starting sustainable businesses, entrepreneurs face special challenges compared to those starting normal businesses. These challenges result from the fact that self-interest and collective interest, which result from the intention of the company, must be reconciled with each other.74 Hoogendoorn, B., van der Zwan, P. & Thurik, R. Sustainable Entrepreneurship: The Role of Perceived Barriers and Risk. J. Bus. Ethics 157, 1133–1154 (2019). Sustainable companies often see their opportunity in markets that are imperfect or characterized by failure. While this is an opportunity (cf. Chapter 2.1), operating under conditions of market failure in the context of environmental and social challenges can also be difficult.

In the context of drivers, the aspect of institutions was addressed earlier. Sustainable entrepreneurs must first initiate changes in institutional conditions in order to achieve changes in laws and policies. An example of this is the inadequate infrastructure for electric cars, which might slow down the expansion. Therefore, adjusting institutional conditions can help entrepreneurs succeed. The above-mentioned aspects imply that sustainable enterprises need a particularly broad knowledge base to operate successfully, since they operate under imperfect markets and unfavorable institutional conditions. Therefore, sustainable companies need to build both internal and external knowledge as well as broad networks.75 Hoogendoorn, B., van der Zwan, P. & Thurik, R. Sustainable Entrepreneurship: The Role of Perceived Barriers and Risk. J. Bus. Ethics 157, 1133–1154 (2019).

Moreover, both the founder and employees must be willing to face these challenges and need to be committed to the company. Employees must also be trained in sustainability, and it is partly a challenge for entrepreneurs to find employees who embody all these attributes. In particular, entrepreneurs who are not yet trained in the area of sustainability must develop tools and processes to effectively implement and achieve sustainability.76 Hoogendoorn, B., van der Zwan, P. & Thurik, R. Sustainable Entrepreneurship: The Role of Perceived Barriers and Risk. J. Bus. Ethics 157, 1133–1154 (2019).

An external barrier that many sustainable companies face arises from the field of finance. First, capital needs to be raised in the early stages; however, several studies have shown the difficulty in generating financial capital.77 DORADO, S. SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURIAL VENTURES: DIFFERENT VALUES SO DIFFERENT PROCESS OF CREATION, NO? J. Dev. Entrep. 11, 319–343 (2006). 78 Purdue, D. Neighbourhood Governance: Leadership, Trust and Social Capital. Urban Stud. 38, 2211–2224 (2001). 79 Sharir, M. & Lerner, M. Gauging the success of social ventures initiated by individual social entrepreneurs. J. World Bus. 41, 6–20 (2006). 80 Zahra, S. A., Gedajlovic, E., Neubaum, D. O. & Shulman, J. M. A typology of social entrepreneurs: Motives, search processes and ethical challenges. J. Bus. Ventur. 24, 519–532 (2009). Furthermore, a large-scale UK study by the Social Enterprise Coalition reported that access to finance is a major barrier to the growth of sustainable enterprises.81 Bertotti, M., Sheridan, K., Tobi, P., Renton, A. & Leahy, G. Measuring the impact of social enterprises. Br. J. Healthc. Manag. 17, 152–156 (2011). When raising financial resources, sustainable companies often also rely on the support of stakeholders, who themselves have different priorities that are usually more profit-driven than those of the sustainable entrepreneur. Investors may be reluctant to invest if they are unable to offset their resource commitments. Financial difficulties for sustainable entrepreneurs may also arise from the lack of standardized measures (cf. Chapter 2.2) for evaluating the performance of sustainable enterprises in terms of social value creation. Nevertheless, it is important to consider that sustainable entrepreneurs perceive financial risk somewhat differently due to the fact that their objectives are somewhat different and are not focused only on financial added value, whereas sustainable entrepreneurs see fulfillment in generating social and sustainable added value.82 Hoogendoorn, B., van der Zwan, P. & Thurik, R. Sustainable Entrepreneurship: The Role of Perceived Barriers and Risk. J. Bus. Ethics 157, 1133–1154 (2019).

Some internal barriers faced by entrepreneurs in general but sustainable entrepreneurs in particular are the risk of failure and the fear of personal failure. No significant differences in risk attitudes and perceptions of financial risk between regular and sustainable entrepreneurs have been found. The results of their research show that sustainable entrepreneurs have a greater fear of personal failure than regular entrepreneurs.83 Borderstep Institut. Sustainable Entrepreneurship. Retrieved on 23/08/2021: https://www.borderstep.de/forschungsthemen/sustainable-entrepreneurship/ (2021). This fear is not unreasonable as the survival rate of new enterprises is low, with 40% of small businesses failing within the first five years and most high-income ventures between 18 and 24 months.84 Greco, A. & de Jong, G. SUSTAINABLE ENTREPRENEURSHIP: DEFINITIONS, THEMES, AND RESEARCH GAPS. (2017).

The aspect of company credibility can serve as an external barrier. As mentioned above, there is currently a general societal shift in thinking toward an increased interest in sustainability aspects. The result has been an increase in market advantage for sustainability focused companies. Many companies attempt to take advantage of this by pretending to integrate sustainability into their business; however, they are only sustainable at first glance. This aspect is also referred to as greenwashing.85 Emrich, C. Nachhaltigkeits-Marketing-Management: Konzept, Strategien, Beispiele. (DE GRUYTER, Oldenburg, 2015). For truly sustainable companies, this results in the problem of setting themselves apart and not being labeled as just another company that pretends to behave sustainably. The sheer number of sustainability certifications also contributes to this problem. Many labels do not actually conceal much of the added value of sustainability, and therefore, it is difficult for consumers who are not intensively involved with the subject to recognize which certifications are actually beneficial to sustainability. One example is the sportswear manufacturer Oceans Apart, which has been accused of misleadingly using sustainability labels issued for their suppliers. This example shows that the usage of seals does not guarantee transparency and that companies should carefully consider the seals used in order to maintain credibility.

Another external barrier are the high end-product costs for costumers. Sustainable products often cost more to produce, thus making the final product more expensive for the consumer than comparable products. Not all customers are willing to spend more money on sustainably produced goods.

Some companies start off under the framework of a good sustainable idea but become commercialized in the course of their development and reach a point where they no longer contribute to sustainability. One example is the company Too Good To Go. The company’s idea was to reduce food waste by offering customers the opportunity to buy food at a reduced price via an app shortly before the expiration date. Both packaged food from supermarkets and prepared food from restaurants and takeaways were included in the range. The company’s original idea and intention was to counteract food waste and help companies become greener without changing the production chain. As the company has grown, critical aspects emerged from a critical commentary by students of the TU Dresden, who are committed to climate justice. On one hand, larger companies generate extra revenues from the overproduction of food, and Too Good To Go also receives more money if more food is left over. Some enterprises exploit customer loyalty and existing market advantages to secure and practice greenwashing. This example of Too Good To Go once again illustrates the conflict between the idea of sustainability on one hand and the aspect of profit generation on the other, which can be applied to other companies in the field of sustainability.

Furthermore, there are the so-called contextual barriers. Some factors can only be indirectly influenced by companies, that is, beyond their direct control. Depending on the environment and situation, these conceptual factors can be diverse and multifaceted in nature, such as government and the above-mentioned aspects of regulation and markets. They also include the impact of geographic location or existing infrastructure.86 Dawo, H., Long, T., Yttredal, E., Wilde Tippett, A. & de Jong, G. Sustainable Entrepreneurship in the North Sea Region: A guidebook of best case examples (2020). Retrieved on 12/08/2021: https://www.waddensea worldheritage.org/sites/default/files/Sustainable%20entrepreneurship%20in%20the%20North%20Sea%20Region%20a%20guidebook_low%20res.pdf

References

- 1Aulinger, A. Entrepreneurship – Selbstverständnis und Perspektiven einer Forschunsgdisziplin. (2003), p. 5.

- 2Aulinger, A. Entrepreneurship – Selbstverständnis und Perspektiven einer Forschunsgdisziplin. (2003).

- 3Schaltegger, S. & Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 20, 222–237 (2011).

- 4Schaltegger S. Sustainable Entrepreneurship als Treiber von Transformation. Retrieved on 24/08/2021: https://www.zukunftsinstitut.de/artikel/sustainable-entrepreneurship-als-treiber-von-transformation/ (2017).

- 5Schaltegger S. Sustainable Entrepreneurship als Treiber von Transformation. Retrieved on 24/08/2021: https://www.zukunftsinstitut.de/artikel/sustainable-entrepreneurship-als-treiber-von-transformation/ (2017).

- 6Gerlach, A.. Sustainable Entrepreneurship and Innovation. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 29-30 (2003).

- 7Schaltegger S. Sustainable Entrepreneurship als Treiber von Transformation. Retrieved on 24/08/2021: https://www.zukunftsinstitut.de/artikel/sustainable-entrepreneurship-als-treiber-von-transformation/ (2017).

- 8Schaltegger, S. & Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 20, 222–237 (2011).

- 9Schaltegger, S. & Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 20, 222–237 (2011).

- 10Ebrahim, A., Battilana, J. & Mair, J. The governance of social enterprises: Mission drift and accountability challenges in hybrid organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 34, 81–100 (2014).

- 11Schaltegger, S. & Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 20, 222–237 (2011).

- 12Bocken, N. M. P., Rana, P. & Short, S. W. Value mapping for sustainable business thinking. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 32, 67–81 (2015).

- 13Breuer, H., Fichter, K., Lüdeke-Freund, F. & Tiemann, I. Sustainability-oriented business model development: principles, criteria and tools. 31 (2018).

- 14Breuer, H. & Lüdeke-Freund, F. Values-Based Innovation Framework – Innovating by What We Care About. (2015).

- 15Fichter, K. Interpreneurship: Nachhaltigkeitsinnovationen in interaktiven Perspektiven eines vernetzenden Unternehmertums. (Metropolis-Verl, Marburg, 2005).

- 16Breuer, H. & Lüdeke-Freund, F. Values-Based Innovation Management – Innovating by What We Care About. (Palgrave, London, 2017).

- 17Muñoz, P. & Cohen, B. Sustainable Entrepreneurship Research: Taking Stock and looking ahead: Sustainable Entrepreneurship Research. Bus. Strategy Environ. 27, 300–322 (2018).

- 18Breuer, H., Fichter, K., Lüdeke-Freund, F. & Tiemann, I. Sustainability-oriented business model development: principles, criteria and tools. 31 (2018).

- 19Breuer, H., Fichter, K., Lüdeke-Freund, F. & Tiemann, I. Sustainability-oriented business model development: principles, criteria and tools. 31 (2018).

- 20Freeman, R. E. Strategic Management: A Stakehlder Approach. (Pitman, Boston, 1984).

- 21Bidmon, C. M. & Knab, S. F. The three roles of business models in societal transitions: New linkages between business model and transition research. J. Clean. Prod. 178, 903–916 (2018).

- 22Lechler, S. Entrepreneurship Education und Nachhaltigkeit. in CSR und Institutionen (ed. Genders, S.) 231–241 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2020).

- 23Kollmann, T., Jung, P. B., Kleine-Stegemann, L., Ataee, J. & de Cruppe, K. Deutscher Startup Monitor. (2020).

- 24Cohen, B. & Winn, M. I. Market imperfections, opportunity and sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 22, 29–49 (2007).

- 25Dean, T. J. & McMullen, J. S. Toward a theory of sustainable entrepreneurship: Reducing environmental degradation through entrepreneurial action. J. Bus. Ventur. 22, 50–76 (2007).

- 26Schaltegger, S., Lüdeke-Freund, F. & Hansen, E. G. Business Models for Sustainability: A Co-Evolutionary Analysis of Sustainable Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Transformation. Organ. Environ. 29, 264–289 (2016).

- 27Schaltegger, S. & Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 20, 222–237 (2011).

- 28Schaltegger, S. & Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 20, 222–237 (2011).

- 29Cohen, B. & Winn, M. I. Market imperfections, opportunity and sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 22, 29–49 (2007).

- 30Hockerts, K. & Wüstenhagen, R. Greening Goliaths versus emerging Davids — Theorizing about the role of incumbents and new entrants in sustainable entrepreneurship. Sustain. Dev. Entrep. 25, 481–492 (2010).

- 31Pacheco, D., Dean, T. & Payne, D. Escaping the Green Prison: Entrepreneurship and the Creation of Opportunities for Sustainable Development. J. Bus. Ventur. 25, 464–480 (2010).

- 32Barbier, E. B. A New Blueprint for a Green Economy. (Routledge, London, 2013).

- 33Hockerts, K. & Wüstenhagen, R. Greening Goliaths versus emerging Davids — Theorizing about the role of incumbents and new entrants in sustainable entrepreneurship. Sustain. Dev. Entrep. 25, 481–492 (2010).

- 34Bocken, N. M. P., Rana, P. & Short, S. W. Value mapping for sustainable business thinking. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 32, 67–81 (2015).

- 35Greco, A. & de Jong, G. SUSTAINABLE ENTREPRENEURSHIP: DEFINITIONS, THEMES, AND RESEARCH GAPS. (2017).

- 36Brundtland Commission. Our Common Future. (1987).

- 37Horne, J. The sustainability impact of new ventures : measuring and managing entrepreneurial contributions to sustainable development. 189 (2019).

- 38Greco, A. & de Jong, G. SUSTAINABLE ENTREPRENEURSHIP: DEFINITIONS, THEMES, AND RESEARCH GAPS. (2017).

- 39European Commission. Proposed approaches to social impact measurement in European Commission legislation and in practice relating to EuSEFs and the EaSI: GECES sub group on impact measurement 2014. (Publications Office, Luxemburg, 2014).

- 40Dichter, S., Adams, T. & Ebrahim, A. The Power of Lean Data. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 14 (2016).

- 41Horne, J. The sustainability impact of new ventures : measuring and managing entrepreneurial contributions to sustainable development. 189 (2019).

- 42Horne, J. The sustainability impact of new ventures : measuring and managing entrepreneurial contributions to sustainable development. 189 (2019).

- 43Reichelt, D. SROI: Social return on investment ; Modellversuch zur Berechnung des gesellschaftlichen Mehrwertes. (Diplomica Verlag, Hamburg, 2009).

- 44Horne, J. The sustainability impact of new ventures : measuring and managing entrepreneurial contributions to sustainable development. 189 (2019).

- 45Parent, M. & Deephouse, D. A Case Study of Stakeholder Identification and Prioritization by Managers. J. Bus. Ethics 75, 1–23 (2007).

- 46Horne, J. The sustainability impact of new ventures : measuring and managing entrepreneurial contributions to sustainable development. 189 (2019).

- 47Statista. Rechtliche Einheiten/ Unternehmen nach Rechtsform und Anzahl der Beschäftigten 2019. (2021). Retrieved on 30/08/2021: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/237346/umfrage/unternehmen-in-deutschland-nach-rechtsform-und-anzahl-der-beschaeftigten

- 48Pott, O. & Pott, A. Entrepreneurship: Unternehmensgründung, Businessplan und Finanzierung, Rechtsformen und gewerblicher Rechtsschutz. (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2015].

- 49Hiller, J. S. The Benefit Corporation and Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 118, 287–301 (2013).

- 50Cetindamar, D. Designed by law: Purpose, accountability, and transparency at benefit corporations. Cogent Bus. Manag. 5, 1423787 (2018).

- 51Osterwalder, A. & Pigneur, Y. Business model generation: A handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers. (Wiley&Sons, New York, 2013).

- 52Fichter, K. & Tiemann, I. Das Konzept ‘Sustainable Business Canvas’ zur Unterstützung nachhaltigkeitsorientierter Geschäftsmodellentwicklung. (2015).

- 53Irina Tiemann & Klaus Fichter. Developing business models with the sustainable business canvas: manual for conducting workshops. (Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg, Oldenburg, 2016).

- 54Bocken, N., Short, S., Rana, P. & Evans, S. A value mapping tool for sustainable business modelling. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 13, 482–497 (2013).

- 55Bocken, N. M. P., Rana, P. & Short, S. W. Value mapping for sustainable business thinking. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 32, 67–81 (2015).

- 56Bocken, N. M. P., Rana, P. & Short, S. W. Value mapping for sustainable business thinking. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 32, 67–81 (2015).

- 57Greco, A. & de Jong, G. SUSTAINABLE ENTREPRENEURSHIP: DEFINITIONS, THEMES, AND RESEARCH GAPS. (2017).

- 58Greco, A. & de Jong, G. SUSTAINABLE ENTREPRENEURSHIP: DEFINITIONS, THEMES, AND RESEARCH GAPS. (2017).

- 59Schlange, L. “WHAT DRIVES SUSTAINABLE ENTREPRENEURS?“. App. Bus. and Ent. Int., 35-45 (2006).

- 60Jahanshahi, A. A. & Brem, A. Sustainability in SMEs: Top Management Teams Behavioral Integration as Source of Innovativeness. Sustainability 9, 1899 (2017).

- 61Kirkwood, J. & Walton, S. What motivates ecopreneurs to start businesses? Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 16, 204–228 (2010).

- 62Greco, A. & de Jong, G. SUSTAINABLE ENTREPRENEURSHIP: DEFINITIONS, THEMES, AND RESEARCH GAPS. (2017).

- 63Schlange, L. “WHAT DRIVES SUSTAINABLE ENTREPRENEURS?“. App. Bus. and Ent. Int., 35-45 (2006).

- 64Steiber, A. & Alänge, S. The Silicon Valley Model: Management for Entrepreneurship. (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2015).

- 65Koe, W.-L., Omar, R. & Majid, I. A. Factors Associated with Propensity for Sustainable Entrepreneurship. Procedia – Soc. Behav. Sci. 130, 65–74 (2014).

- 66The Limits to growth: a report for the Club of Rome’s project on the predicament of mankind. (Universe Books, New York, 1972).

- 67Herlyn, E. & Lévy-Tödter, M. Die Agenda 2030 als Magisches Vieleck der Nachhaltigkeit. (Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH, 2020).

- 68Köhn-Ladenburger, C. Marketing für LOHAS: Kommunikationskonzepte für anspruchsvolle Kunden. (Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden, 2013).

- 69Enders, B. & Weber, T. Nachhaltiges Konsumentenverhalten – Welche Nachhaltigkeitssiegel beeinflussen den Verbraucher? in CSR und Marketing (eds. Stehr, C. & Struve, F.) 197–213 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2017).

- 70Pinkse, J. & Groot, K. Sustainable Entrepreneurship and Corporate Political Activity: Overcoming Market Barriers in the Clean Energy Sector. Entrep. Theory Pract. 39, 633–654 (2015).

- 71Greco, A. & de Jong, G. SUSTAINABLE ENTREPRENEURSHIP: DEFINITIONS, THEMES, AND RESEARCH GAPS. (2017).

- 72Pacheco, D., Dean, T. & Payne, D. Escaping the Green Prison: Entrepreneurship and the Creation of Opportunities for Sustainable Development. J. Bus. Ventur. 25, 464–480 (2010).

- 73Greco, A. & de Jong, G. SUSTAINABLE ENTREPRENEURSHIP: DEFINITIONS, THEMES, AND RESEARCH GAPS. (2017).

- 74Hoogendoorn, B., van der Zwan, P. & Thurik, R. Sustainable Entrepreneurship: The Role of Perceived Barriers and Risk. J. Bus. Ethics 157, 1133–1154 (2019).

- 75Hoogendoorn, B., van der Zwan, P. & Thurik, R. Sustainable Entrepreneurship: The Role of Perceived Barriers and Risk. J. Bus. Ethics 157, 1133–1154 (2019).

- 76Hoogendoorn, B., van der Zwan, P. & Thurik, R. Sustainable Entrepreneurship: The Role of Perceived Barriers and Risk. J. Bus. Ethics 157, 1133–1154 (2019).

- 77DORADO, S. SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURIAL VENTURES: DIFFERENT VALUES SO DIFFERENT PROCESS OF CREATION, NO? J. Dev. Entrep. 11, 319–343 (2006).

- 78Purdue, D. Neighbourhood Governance: Leadership, Trust and Social Capital. Urban Stud. 38, 2211–2224 (2001).

- 79Sharir, M. & Lerner, M. Gauging the success of social ventures initiated by individual social entrepreneurs. J. World Bus. 41, 6–20 (2006).

- 80Zahra, S. A., Gedajlovic, E., Neubaum, D. O. & Shulman, J. M. A typology of social entrepreneurs: Motives, search processes and ethical challenges. J. Bus. Ventur. 24, 519–532 (2009).

- 81Bertotti, M., Sheridan, K., Tobi, P., Renton, A. & Leahy, G. Measuring the impact of social enterprises. Br. J. Healthc. Manag. 17, 152–156 (2011).

- 82Hoogendoorn, B., van der Zwan, P. & Thurik, R. Sustainable Entrepreneurship: The Role of Perceived Barriers and Risk. J. Bus. Ethics 157, 1133–1154 (2019).

- 83Borderstep Institut. Sustainable Entrepreneurship. Retrieved on 23/08/2021: https://www.borderstep.de/forschungsthemen/sustainable-entrepreneurship/ (2021).

- 84Greco, A. & de Jong, G. SUSTAINABLE ENTREPRENEURSHIP: DEFINITIONS, THEMES, AND RESEARCH GAPS. (2017).

- 85Emrich, C. Nachhaltigkeits-Marketing-Management: Konzept, Strategien, Beispiele. (DE GRUYTER, Oldenburg, 2015).

- 86Dawo, H., Long, T., Yttredal, E., Wilde Tippett, A. & de Jong, G. Sustainable Entrepreneurship in the North Sea Region: A guidebook of best case examples (2020). Retrieved on 12/08/2021: https://www.waddensea worldheritage.org/sites/default/files/Sustainable%20entrepreneurship%20in%20the%20North%20Sea%20Region%20a%20guidebook_low%20res.pdf

- 1Aulinger, A. Entrepreneurship – Selbstverständnis und Perspektiven einer Forschunsgdisziplin. (2003), p. 5.

- 2Aulinger, A. Entrepreneurship – Selbstverständnis und Perspektiven einer Forschunsgdisziplin. (2003).

- 3Schaltegger, S. & Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 20, 222–237 (2011).

- 4Schaltegger S. Sustainable Entrepreneurship als Treiber von Transformation. Retrieved on 24/08/2021: https://www.zukunftsinstitut.de/artikel/sustainable-entrepreneurship-als-treiber-von-transformation/ (2017).

- 5Schaltegger S. Sustainable Entrepreneurship als Treiber von Transformation. Retrieved on 24/08/2021: https://www.zukunftsinstitut.de/artikel/sustainable-entrepreneurship-als-treiber-von-transformation/ (2017).

- 6Gerlach, A.. Sustainable Entrepreneurship and Innovation. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 29-30 (2003).

- 7Schaltegger S. Sustainable Entrepreneurship als Treiber von Transformation. Retrieved on 24/08/2021: https://www.zukunftsinstitut.de/artikel/sustainable-entrepreneurship-als-treiber-von-transformation/ (2017).

- 8Schaltegger, S. & Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 20, 222–237 (2011).

- 9Schaltegger, S. & Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 20, 222–237 (2011).

- 10Ebrahim, A., Battilana, J. & Mair, J. The governance of social enterprises: Mission drift and accountability challenges in hybrid organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 34, 81–100 (2014).

- 11Schaltegger, S. & Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 20, 222–237 (2011).

- 12Bocken, N. M. P., Rana, P. & Short, S. W. Value mapping for sustainable business thinking. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 32, 67–81 (2015).

- 13Breuer, H., Fichter, K., Lüdeke-Freund, F. & Tiemann, I. Sustainability-oriented business model development: principles, criteria and tools. 31 (2018).

- 14Breuer, H. & Lüdeke-Freund, F. Values-Based Innovation Framework – Innovating by What We Care About. (2015).

- 15Fichter, K. Interpreneurship: Nachhaltigkeitsinnovationen in interaktiven Perspektiven eines vernetzenden Unternehmertums. (Metropolis-Verl, Marburg, 2005).

- 16Breuer, H. & Lüdeke-Freund, F. Values-Based Innovation Management – Innovating by What We Care About. (Palgrave, London, 2017).

- 17Muñoz, P. & Cohen, B. Sustainable Entrepreneurship Research: Taking Stock and looking ahead: Sustainable Entrepreneurship Research. Bus. Strategy Environ. 27, 300–322 (2018).

- 18Breuer, H., Fichter, K., Lüdeke-Freund, F. & Tiemann, I. Sustainability-oriented business model development: principles, criteria and tools. 31 (2018).

- 19Breuer, H., Fichter, K., Lüdeke-Freund, F. & Tiemann, I. Sustainability-oriented business model development: principles, criteria and tools. 31 (2018).

- 20Freeman, R. E. Strategic Management: A Stakehlder Approach. (Pitman, Boston, 1984).

- 21Bidmon, C. M. & Knab, S. F. The three roles of business models in societal transitions: New linkages between business model and transition research. J. Clean. Prod. 178, 903–916 (2018).

- 22Lechler, S. Entrepreneurship Education und Nachhaltigkeit. in CSR und Institutionen (ed. Genders, S.) 231–241 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2020).

- 23Kollmann, T., Jung, P. B., Kleine-Stegemann, L., Ataee, J. & de Cruppe, K. Deutscher Startup Monitor. (2020).

- 24Cohen, B. & Winn, M. I. Market imperfections, opportunity and sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 22, 29–49 (2007).

- 25Dean, T. J. & McMullen, J. S. Toward a theory of sustainable entrepreneurship: Reducing environmental degradation through entrepreneurial action. J. Bus. Ventur. 22, 50–76 (2007).

- 26Schaltegger, S., Lüdeke-Freund, F. & Hansen, E. G. Business Models for Sustainability: A Co-Evolutionary Analysis of Sustainable Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Transformation. Organ. Environ. 29, 264–289 (2016).

- 27Schaltegger, S. & Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 20, 222–237 (2011).

- 28Schaltegger, S. & Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 20, 222–237 (2011).

- 29Cohen, B. & Winn, M. I. Market imperfections, opportunity and sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 22, 29–49 (2007).

- 30Hockerts, K. & Wüstenhagen, R. Greening Goliaths versus emerging Davids — Theorizing about the role of incumbents and new entrants in sustainable entrepreneurship. Sustain. Dev. Entrep. 25, 481–492 (2010).

- 31Pacheco, D., Dean, T. & Payne, D. Escaping the Green Prison: Entrepreneurship and the Creation of Opportunities for Sustainable Development. J. Bus. Ventur. 25, 464–480 (2010).

- 32Barbier, E. B. A New Blueprint for a Green Economy. (Routledge, London, 2013).

- 33Hockerts, K. & Wüstenhagen, R. Greening Goliaths versus emerging Davids — Theorizing about the role of incumbents and new entrants in sustainable entrepreneurship. Sustain. Dev. Entrep. 25, 481–492 (2010).

- 34Bocken, N. M. P., Rana, P. & Short, S. W. Value mapping for sustainable business thinking. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 32, 67–81 (2015).

- 35Greco, A. & de Jong, G. SUSTAINABLE ENTREPRENEURSHIP: DEFINITIONS, THEMES, AND RESEARCH GAPS. (2017).

- 36Brundtland Commission. Our Common Future. (1987).

- 37Horne, J. The sustainability impact of new ventures : measuring and managing entrepreneurial contributions to sustainable development. 189 (2019).

- 38Greco, A. & de Jong, G. SUSTAINABLE ENTREPRENEURSHIP: DEFINITIONS, THEMES, AND RESEARCH GAPS. (2017).

- 39European Commission. Proposed approaches to social impact measurement in European Commission legislation and in practice relating to EuSEFs and the EaSI: GECES sub group on impact measurement 2014. (Publications Office, Luxemburg, 2014).

- 40Dichter, S., Adams, T. & Ebrahim, A. The Power of Lean Data. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 14 (2016).

- 41Horne, J. The sustainability impact of new ventures : measuring and managing entrepreneurial contributions to sustainable development. 189 (2019).

- 42Horne, J. The sustainability impact of new ventures : measuring and managing entrepreneurial contributions to sustainable development. 189 (2019).

- 43Reichelt, D. SROI: Social return on investment ; Modellversuch zur Berechnung des gesellschaftlichen Mehrwertes. (Diplomica Verlag, Hamburg, 2009).

- 44Horne, J. The sustainability impact of new ventures : measuring and managing entrepreneurial contributions to sustainable development. 189 (2019).

- 45Parent, M. & Deephouse, D. A Case Study of Stakeholder Identification and Prioritization by Managers. J. Bus. Ethics 75, 1–23 (2007).

- 46Horne, J. The sustainability impact of new ventures : measuring and managing entrepreneurial contributions to sustainable development. 189 (2019).

- 47Statista. Rechtliche Einheiten/ Unternehmen nach Rechtsform und Anzahl der Beschäftigten 2019. (2021). Retrieved on 30/08/2021: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/237346/umfrage/unternehmen-in-deutschland-nach-rechtsform-und-anzahl-der-beschaeftigten

- 48Pott, O. & Pott, A. Entrepreneurship: Unternehmensgründung, Businessplan und Finanzierung, Rechtsformen und gewerblicher Rechtsschutz. (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2015].

- 49Hiller, J. S. The Benefit Corporation and Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 118, 287–301 (2013).

- 50Cetindamar, D. Designed by law: Purpose, accountability, and transparency at benefit corporations. Cogent Bus. Manag. 5, 1423787 (2018).

- 51Osterwalder, A. & Pigneur, Y. Business model generation: A handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers. (Wiley&Sons, New York, 2013).