Authors: Joost Horstmann, Norma Jurado van Bürck, Henri Pink, Christianna Angela Roth

Last updated: October 1st 2023

1. Definition and relevance

Business ethics belongs to the discipline of applied ethics, defined as the interaction of ethics and business.1 De George, R. T. The status of business ethics: Past and future. Journal of Business ethics, 6, 201-211 (1987). Precisely, business ethics is defined as the discipline that is concerned with the rightness, wrongness, fairness or justice of actions, decisions, policies, and practices that take place within a business context or in the workplace.1 De George, R. T. The status of business ethics: Past and future. Journal of Business ethics, 6, 201-211 (1987).

1.1 Distinction from similar topics

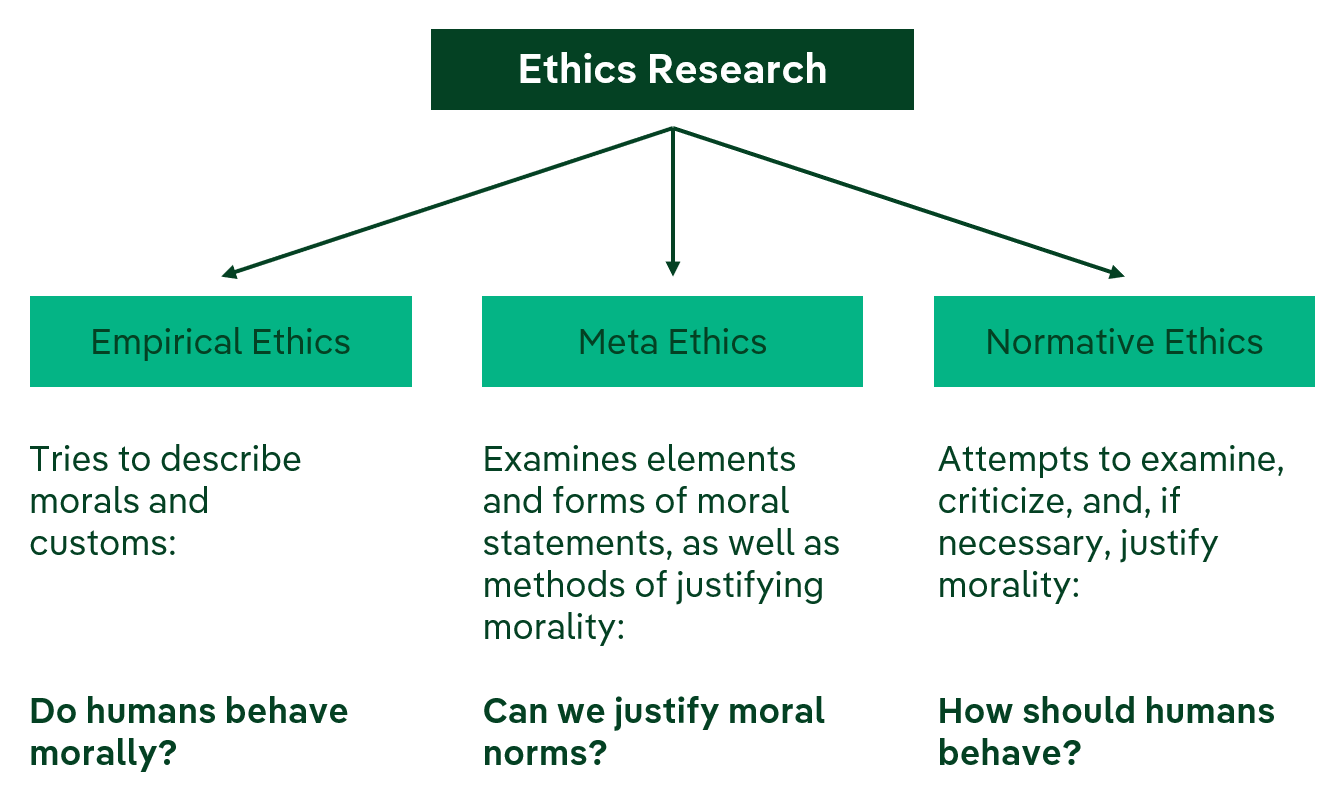

Before one is able to describe the content of the field of business ethics in more detail, it is important to clearly define and delineate the concepts of “ethics,” “morality,” and “corporate social responsibility,” which are key to understanding what business ethics is about. Ethics and morality are broader terms that encompass ethical principles and values in various life contexts, including business context. Morality refers to the principles and values that guide human behavior and is often influenced by cultural, religious, or philosophical beliefs. Ethics encompasses principles, values, and norms that guide human behavior in various contexts, including personal life, work, and society. Ethics serves as a reflective theory of morality and analyses and critically evaluates moral considerations and principles.2 Köberer, N., & Köberer, N. Zur Differenz von Ethik und Moral. Advertorials in Jugendprintmedien: Ein medienethischer Zugang, 21-24. (2014). In this context, ethics research can be divided into three main categories: (1) empirical ethics, (2) meta ethics, and (3) normative ethics (see Figure 1). While empirical ethics tries to describe morals and customs (i.e., how humans actually behave), meta ethics examines the elements and forms of moral statements, as well as methods of justifying morality (i.e., seeks to answer if we can justify moral norms). Normative ethics, finally, attempts to examine, criticize, and justify morality (i.e., how humans should behave).25Carroll, A. B., Brown, J. A. & Buchholtz, A. K. Business & society. Ethics, sustainability, and stakeholder management (Cengage Learning, Boston, MA, 2018)

While general ethics develops the conceptual and empirical foundations of what is right and fair conduct or behavior and, if necessary, also systematically reflects on them, the field of applied business ethics transfers these insights to the specific problem domain of firms.26 Gatewood, R. D., & Carroll, A. B. Assessment of ethical performance of organization members: A conceptual framework. Academy of Management Review, 16(4), 667-690. (1991). In this context, CSR is a specific aspect of business ethics that emphasizes a company’s social and environmental responsibilities beyond profit-making decisions. CSR is about the company’s responsibility to society and the environment, is considered voluntary and goes beyond legal requirements, whereas adhering to business ethics often includes compliance with legal regulations since it focuses on ethical standards and values governing its internal conduct.27 Goel, M. & Ramanathan, Ms. P. E. Business Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility – Is there a Dividing Line? Procedia Economics and Finance 11, 49–59 (2014).

1.2 Relevance of business ethics

So, why is business ethics relevant for firms? By considering the impact of their actions on the society and the environment, firms can avoid action that may lead to negative consequences.28 Lindgreen, A., Swaen, V. & Maon, F. Introduction: corporate social responsibility implementation. Journal of Business Ethics 85, 251–256 (2009). In other words, ethical standards can help companies identify and mitigate risks in preventing unethical actions that could lead to financial losses, or damage to the company’s reputation. As a result, ethical behavior can help builds trust and a positive reputation with important stakeholders, such as policy makers, customers, employees, investors, and the public.

Pertaining to policy makers, ethical practices help firms comply with laws and regulations. Violating ethical standards can lead to legal trouble and damage to a company’s reputation.

Pertaining to customers, in upholding high ethical standards, companies can gain a competitive advantage by attracting customers that value ethics.5 Lindgreen, A., Swaen, V. & Maon, F. Introduction: corporate social responsibility implementation. Journal of Business Ethics 85, 251–256 (2009). Also, the trust companies build through ethicsl behavior can lead to increased customer loyalty and positive recommendations. As a result, customers are also more likely to continue supporting companies they perceive as ethical and socially responsible.

Pertaining to employees, ethical behavior can increase the motivation of the company’s workforce. Higher morale and job contentment can lead to increased productivity, lower turnovers, and reduced recruitment costs.

Pertaining to investors, capital markets increasingly consider whether companies are value-driven, especially according to the ESG factors environmental, societal, and governance.29 Schnebel, E., & Bienert, M. A. Implementing ethics in business organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 53, 203-211 (2004).

Finally, pertaining to the general public, ethical business can manifest as corporate social responsibility initiative, which benefit communities and the environment. In a globalized world, ethical behavior is becoming increasingly important. Companies operating internationally must navigate different cultural and ethical environments, so adherence to ethical principles is fundamental to avoid misunderstandings and conflicts.30 Morrison, A. Integrity and Global Leadership. Journal of Business Ethics 31, 65–76 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010789324414

Despite these many advantages that ethical behavior brings, it is connected with considerable costs, especially in the short run, which often leads to unethical behavior of companies. For example, many companies that focus on short-term profit maximization and attempt to resolve crises, engage in unethical practices to cut costs, even if it may damage the company’s reputation. Highly competitive industries and unrealistic market expectations often also demand that companies squeeze their costs and neglect ethical behavior. When acting with different cultures, finding a common ethical ground can be difficult. Finally, monopoly or oligopoly positions can also lead to unethical behavior because of the lack of pressure to adhere to ethical practices.31 Shaw, W. H., & Barry, V. Moral issues in business. Cengage Learning. (2015).

2. Origin and development of business ethics

2.1 The origin of business ethics

The core idea of business ethics emerged in the 1950s and was initially called “ethics in business”. During this time, the first university courses and books emerged. As important as the first publications were, they only represented a sub-field of ethics and not an independent discipline. Ethics was merely applied in business similar to how researchers applied it in the fields of government, politics, sexual life, family and private life and all other areas of life.1 De George, R. T. The status of business ethics: Past and future. Journal of Business ethics, 6, 201-211 (1987). In the 1960s, a strong anti-business attitude developed among many as they attacked the military-industrial establishment in response to the Vietnam war and the cold war and in consequence of the coming to terms with the colonial era and slavery. In addition, the development of modern industries, the rise of ecological problems, pollution and the toxic and nuclear waste industries were also met with resentment. With the rise of social issue courses in the universities and a growing number of texts and treaties on corporate social responsibility, the public pressure on social demands on businesses increased rapidly.1 De George, R. T. The status of business ethics: Past and future. Journal of Business Ethics, 6, 201-211 (1987).

2.2 The development towards an institutionalized academic field

During the 1970s, several central issues emerged, and some authors began to develop a systematic approach, which is fleshed out in Section 3. Management professors increasingly wrote and taught about corporate social responsibility. By the end of the 1970s, business ethics emerged and so much work had been done that the term “business ethics” became common parlance.1 De George, R. T. The status of business ethics: Past and future. Journal of Business ethics, 6, 201-211 (1987). In 1980, the internationally recognized non-governmental organization Society for Business Ethics was founded to promote the advancement and understanding of ethics in business.32 N.a. Society for Business Ethics: Who We Are (2023). https://sbeonline.org/about-us/. (accessed on: 2023/08/26)

The increasing publication of journals, over 500 different courses offered by US colleges and over 40,000 graduates in business ethics show the rapid growth of the young discipline. By 1985, business ethics had developed into an institutionalized academic field, albeit one that was still in the definition phase.1 De George, R. T. The status of business ethics: Past and future. Journal of Business ethics, 6, 201-211 (1987). In 1986, the organization ‘Defense Industry Initiative on Business Ethics and Conduct’ developed “principles for guiding business ethics and conduct”10 Ferrell, O. C., & Fraedrich, J. Business ethics: Ethical decision making and cases. Cengage learning (2021). to establish codes of conduct and ethics trainings in companies. Based on the principles of the defense industry initiative, the ‘Federal Sentencing Guidelines for Organizations’ (FSGO) implemented policies that legislate incentives for companies to prevent misconduct, such as the development of effective internal legal and ethical compliance programs.10 Ferrell, O. C., & Fraedrich, J. Business ethics: Ethical decision making and cases. Cengage learning (2021). The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) was founded in 1997 and today has become the globally most widely used non-financial reporting standard. As a global network for companies, non-governmental organizations, and a wide variety of other stakeholder groups, GRI formulates guidelines, principles, and indices based on which companies can determine their economic, social, and ecological goals, measure the achievement of goals and report on the results. (GRI, 2023). The GRI example illustrates the pressure on companies and organizations regarding stakeholder expectations and the enormous complexity and dispersion of the issue.33 Rüttinger, L., Griestop, L., Heidegger, J. UmSoRess Steckbrief: International Cyanide Management Code. Umweltbundesamt (2015).

Even though business ethics appeared to become more institutionalized by the 2000s, of course not all companies fully embraced the “public’s desire for high ethical standards”10 Ferrell, O. C., & Fraedrich, J. Business ethics: Ethical decision making and cases. Cengage learning (2021). On a global level, this led to a series of uncovered accounting scandals and the publication of falsified financial reports. Such abuses intensified public and political demands for an improvement of ethical standards in business.10 Ferrell, O. C., & Fraedrich, J. Business ethics: Ethical decision making and cases. Cengage learning (2021). Consequently, in 2002, the US congress implemented the Sarbanes-Oxley Act to set rules and standards for companies with the goal to increase transparency in the economic market. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act and the FSGO “institutionalized the need to discover and address ethical and legal risks”10 Ferrell, O. C., & Fraedrich, J. Business ethics: Ethical decision making and cases. Cengage learning (2021). to prevent ethical misconduct before a crisis occurs.

2.3 Business ethics today

Today, business ethics has established itself as an imoprtant academic field, although its practical impact remains debated. The public in many countries proposes ethical demands towards companies that need to be considered and, if necessary, implemented. In this context, and due to growing controversial issues faced by a company, especially through comparably new issues such as privacy violation and social media, business ethics is crucial to be implemented.1 De George, R. T. The ethics of information technology and business. John Wiley & Sons (2008).

3. Ethical theories from economic perspective

There are three most significant groups of theories in business ethics, which represent different approaches to explaining human behavior.

3.1 Teleological theories

For a long time, teleological theories and the utilitarian approach served as the foundation for assumptions about economic decision-making by individuals in their daily lives. “Teleology” comes from the Greek term “telos”, which means “end”. Teleological theories of ethics are based on the view that a decision behind a certain behavior must be based on an evaluation of a corresponding outcome. An example for a teleological theory is Utilitariasm, of which two influential philosophers were Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill.

In the teleological ethics approach to business ethics, maximizing utility is equated with maximizing profit or capital. To this end, cost-benefit analysis can be applied in decision-making or project evaluation, as it provides for a calculation of project costs and an allocation of monetary value to the overall project outcome.12 Baumane-Vitolina, I., Cals, I. & Sumilo, E. Is Ethics Rational? Teleological, Deontological and Virtue Ethics Theories Reconciled in the Context of Traditional Economic Decision Making. Procedia Economics and Finance 39, 108–114 (2016). However, applying the principles of utilitarianism also means, considering the interests of all stakeholders and the consequences resulting from the measures applied. Therefore, the ultimate goal of teleological theories is to maximize the happiness as the greatest value.

The advantage of teleological theories is that it forces individuals to think about the consequences (and affected stakeholders) of action, while providing sufficient leeway for decision making. A downside of teleological approaches is that some actions may be inherently wrong according to the law or basic ethical principles, implying that considering specific actions as part of a utilitarian approach may not be appropriate. Also, a core problem of teleological approaches remains that it is unclear how one can assess and predict the consequences of decisions and their impact on the hapiness of stakeholders.

3.2 Deontological theories

Deontological ethics and Kant’s categorical imperative stress universal moral principles and a set of rules that should be fulfilled. The name deontology comes from the Greek “Deon”, which translates as “duty”. According to the founder, the 18th century German philosopher Immanuel Kant, classical deontological theories emphasize the importance of the motives behind a behavior besides the outcome. Therefore, ethical behavior is determined by a duty rather than a reward. The categorical imperatives or unconditional principles (without exception) by Kant are defined to be universal and should be followed regardless of the circumstances. In the social and economic context, the focus is primarily on five core principles: Beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, justice, and responsibility.34 Micewski, E. R., & Troy, C. Business ethics–deontologically revisited. Journal of Business Ethics, 72, 17-25 (2007). A core advantage of deontological theories compared to teleological theories lies in the clear guidance they provide for decision making. A major problem is that different duties and rights one can think of as guidelines may be conflicting and may differ in their importance, leading to the question how they should be weighed.

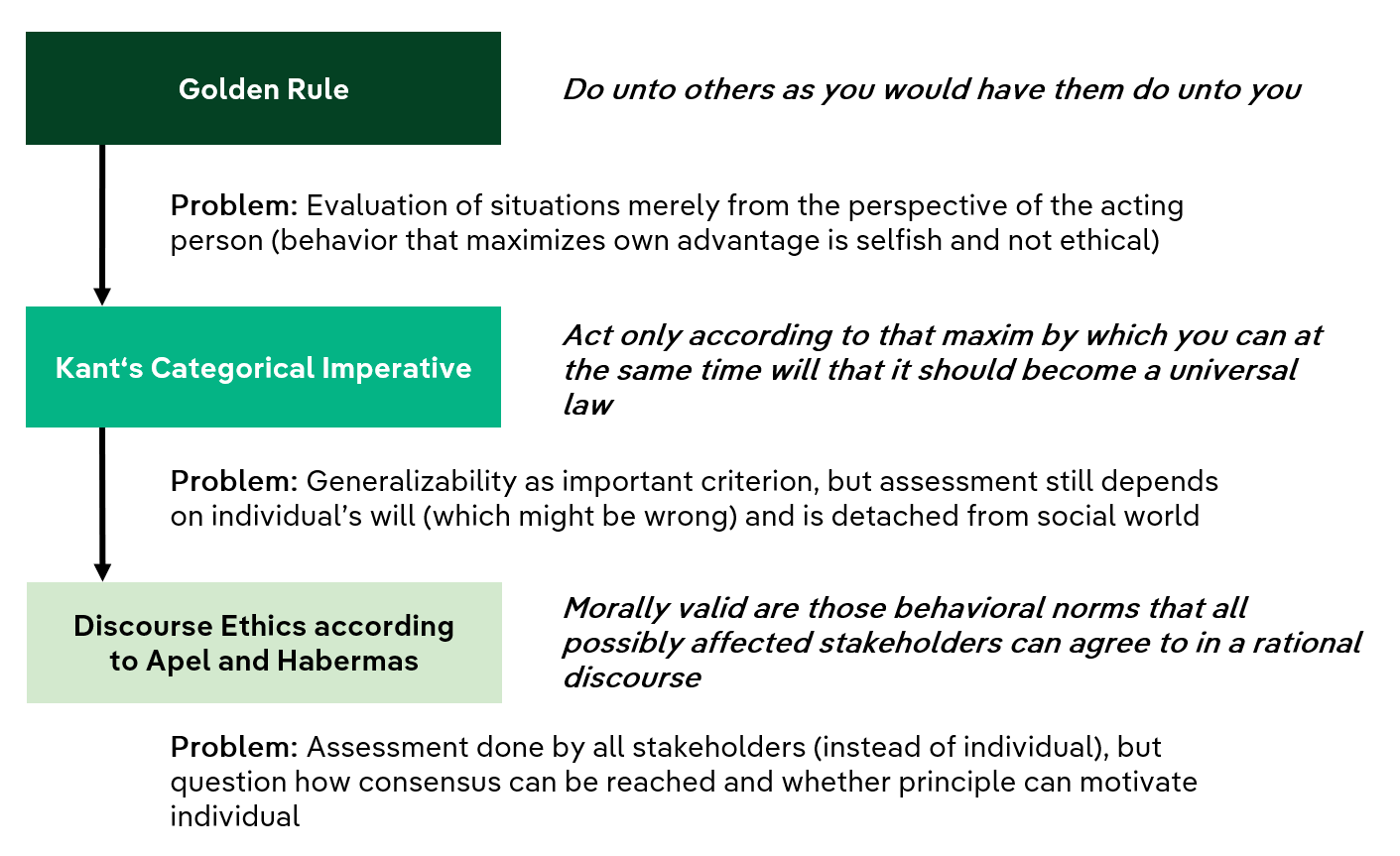

One of the oldes moral principles, which appears to have originated in several different places in ancient Greece, China, and Israel around 600 B.C., is the Golden Rule, which states “Do unto others as you would have other do unto you”14 Burton, B. K., & Goldsby, M. The golden rule and business ethics: An examination. Journal of Business Ethics, 56, 371-383 (2005). . From a deontological perspective, holding onto the Golden Rule is a moral duty, and one should act in line with this principle because it is the right thing to do, regardless of the potential outcomes and consequences.14 Burton, B. K., & Goldsby, M. The golden rule and business ethics: An examination. Journal of Business Ethics, 56, 371-383 (2005). . John Stuart Mill regarded the Rule as the “perfection of utilitarian morality”35 Mill, J. S. Utilitarianism. In Seven masterpieces of philosophy (pp. 329-375). Routledge (2016). . It provides a clear moral guideline without necessarily considering the specific consequences of an action and serves as a simple set of rules and as an approach for a universally applicable moral code in times of globalization. Further, the Golden Rule promotes open and empathetic communication. A key problem with the golden rule is that it implies that situations should merely be evaluated from the perspective of the acting person, which may lead to outcomes that are not ideal from a broader societal perspective.

Therefore, Kant developed the so-called Categorical Imperative, which suggests that one should “act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.” Kant claimed that this rule is more general than the Golden Rule and better able to establish moral duties. Despite this focus on greater generalizability, a core problem with Kant’s Categorical Imperative remains that the assessment of morality still depends on an individual’s will (which might be wrong) and is detached from the social world.

Addressing the criticism of Kant’s Categorical Imperative, Apel and Habermas developed the so-called “discourse ethics,” which suggests that “morally valid are those behavioral norms that all possibly affected stakeholders can agree to in a rational discourse.” In this sense, the assessment of morality is no longer left to an individual but to all stakeholders whoc need to engage in an open, rational, and inclusive dialogue.36 Langenberg, S. Habermas and his communicative perspective. Humanistic Ethics in the Age of globality. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 151-168 (2011). A key problem with Discourse Ethics, however, is the question how a consensus among the different stakeholders (with potentially conflicting interests) can be reached and whether the relatively abstract principle can be used to motivate individual decision making in specific situations

Figure 2 summarizes the evolution of deontological theories in ethics.

3.3 Virtue ethics theories

Virtue ethics, developed by Aristotle in ancient Greek, embeds the individual in an intricate web of embedded relationships that is “the only path to achieve real happiness and satisfaction”12 Baumane-Vitolina, I., Cals, I., & Sumilo, E. Is ethics rational? Teleological, deontological and virtue ethics theories reconciled in the context of traditional economic decision making. Procedia Economics and Finance, 39, 108-114 (2016). The approach links the pursuit of better outcomes with adherence to certain moral standards. From the perspective of virtue ethics, an action is considered right if a morally virtuous person would do the same under similar circumstances. It is character-based and, unlike the teleological and deontological perspectives, focuses on the moral qualities of the individual rather than duties or consequences. Virtue ethics assesses the morality of individual actions and serves as a guiding framework for the behavior and qualities to which a reasonable person should aspire. It emphasizes contextual factors of behavior and prevailing social values.12 Baumane-Vitolina, I., Cals, I., & Sumilo, E. Is ethics rational? Teleological, deontological and virtue ethics theories reconciled in the context of traditional economic decision making. Procedia Economics and Finance, 39, 108-114 (2016). In business context, Virtue ethics focuses on the individual employee, asking about the individual values and (interpersonal) behavior of employees. Furthermore, virtue ethics enables individuals to embody character traits, such as integrity and diversity.37 Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., Wicks, A. C., Parmar, B. L., & De Colle, S. Stakeholder theory: The state of the art (2010). The fact that in virtue ethics or aretaic theories, decisions are linked to individuals’ character and appeal to individuals’ conscience is a major advantage of these theories. A core problem is that even if the motives of an individual are correct, this may still lead to unethical behavior.

4. Academic discourse in Business Ethics

4.1 Central Topics

The purpose of firms

The purpose of firms has been a central topic linked to the field of business ethics for the past decades.18 Dacin, M. T., Harrison, J. S., Hess, D., Killian, S. & Roloff, J. Business Versus Ethics? Thoughts on the Future of Business Ethics. Journal of Business Ethics 180, 863–877; 10.1007/s10551-022-05241-8 (2022). The discourse revolves around the relationship between business and society at large and in how far corporations carry social responsibility. Over the past decades, three fundamental perspectives have emerged.

The shareholder value perspective claims that there is no social responsibility of firms, as firms merely exist to maximize profits, thus creating value for their shareholders. In an influential essay published in the New York Times in 1970, Milton Friedman argues that the exertion of a social responsibility beyond profit maximization within the boundaries of the law is equivalent to taxation and the expenditure of tax proceeds, which are responsibilities of the government alone.38 Friedman, M. (1970, September 13). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. New York Times Magazine, 122-124.

With his 1984 book Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach, Edward Freeman has brought the idea of Stakeholder Theory to the academic discourse.39 Freeman, R. E. Strategic management. A stakeholder approach (Pitman, Boston, Mass., 1984). An organization’s stakeholders are typically defined as all groups or individuals who can affect or are affected by the organization, although a narrower definition exists that only includes those groups that are vital to the organization’s survival and success.21 Melé, D. The View and Purpose of the Firm in Freeman’s Stakeholder Theory. Philos. of Manag. 8, 3–13; 10.5840/pom2009832 (2009). Stakeholder Theory differs from most strategic management theories by explicitly addressing morals and values as central features of management.40 Phillips, R., Freeman, R. E. & Wicks, A. C. What Stakeholder Theory Is Not. Business Ethics Quarterly 13, 479–502 (2003). The underlying stakeholder value perspective sees the purpose of firms in creating value for stakeholders. 21 Melé, D. The View and Purpose of the Firm in Freeman’s Stakeholder Theory. Philos. of Manag. 8, 3–13; 10.5840/pom2009832 (2009). In this context, Freeman defines Stakeholders as financiers, customers, suppliers, employees, and communities.41 Freeman, R. E. The Politics of Stakeholder Theory: Some Future Directions. Business Ethics Quarterly 4, 409–421; 10.2307/3857340 (1994).

The shared value perspective goes a step further and defines the purpose of firms as the creation of shared value, a concept developed by Michael Porter and Mark Kramer, that is built upon an interdependency between corporations and society, overcoming the trade-off between economic profit and societal benefits underlying previous concepts.42 Porter, M. & Kramer, M. The Big Idea: Creating Shared Value. How to Reinvent Capitalism—and Unleash a Wave of Innovation and Growth. Harvard Business Review 89, 62–77 (2011).

Law and Business Ethics

Another central topic in the field of business ethics deals with the intersection of law and ethics. Typically, ethics is seen as a layer above the law, in the sense that ethical behavior goes beyond legal requirements.25 Carroll, A. B., Brown, J. A. & Buchholtz, A. K. Business & society. Ethics, sustainability, and stakeholder management (Cengage Learning, Boston, MA, 2018). An example of a different managerial interpretation of law and ethics can be seen in the Enron scandal, when management carefully tried to stay within the law’s lines while committing fraud. Although illegal behavior is in many cases regarded as unethical, there are some cases where the law and ethical standards diverge. This can be the case when the development of societal norms and technologies are faster than legislation. Examples for this are the use of artificial intelligence in human resource contexts18 Dacin, M. T., Harrison, J. S., Hess, D., Killian, S. & Roloff, J. Business Versus Ethics? Thoughts on the Future of Business Ethics. J Bus Ethics 180, 863–877; 10.1007/s10551-022-05241-8 (2022). , civil disobedience, e.g., in the civil rights movement25 Carroll, A. B., Brown, J. A. & Buchholtz, A. K. Business & society. Ethics, sustainability, and stakeholder management (Cengage Learning, Boston, MA, 2018). , and the often-illegal but arguably ethical activities of ride-sharing companies like Uber43 Young, C. Putting the Law in Its Place: Business Ethics and the Assumption that Illegal Implies Unethical. Journal of Business Ethics 160, 35–51 (2019). .

Intercultural Perspectives

Another stream of literature deals with business ethics across cultures, countries, or religions. 27 Ermasova, N. Cross-cultural issues in business ethics: A review and research agenda. Int’l Jnl of Cross Cultural Management 21, 95–121; 10.1177/1470595821999075 (2021). Most of the studies use the Dimensions of Culture model by Geert Hofstede44 Hofstede, G. Culture and Organizations. International Studies of Management & Organization 10, 15–41; 10.1080/00208825.1980.11656300 (1980). 29 Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture 2; 10.9707/2307-0919.1014 (2011). . The model, which was developed based on the exploration of a database of more than 100,000 questionnaires on values and sentiments of IBM employees from over 50 countries, identifies six dimensions, representing aspects of culture that can be measured relative to other cultures: Power Distance, Uncertainty Avoidance, Individualism versus Collectivism, Masculinity versus Femininity, Long Term versus Short Term Orientation, and Indulgence versus Restraint.29 Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture 2; 10.9707/2307-0919.1014 (2011). Main topics in the field of cross-cultural business ethics are the business environment, institutions and culture perceptions, business education and training in different cultural contexts, whistleblowing in different cultural contexts, and the impact of demographic factors on business ethics perception across countries. 27 Ermasova, N. Cross-cultural issues in business ethics: A review and research agenda. Int’l Jnl of Cross Cultural Management 21, 95–121; 10.1177/1470595821999075 (2021).

4.2 Theories and models of ethical decision-making

Four Component Model

Rest’s Four Component Model30 Rest, J. R. Moral development. Advances in research and theory (Praeger, New York, N.Y., 1986). is a central model in the context of ethical decision-making. After developing a multiple-choice test for indexing moral development through hypothetical ethical dilemmas, in 1986, the American psychologist James Rest established the Four Component Model of Morality. To explain the moral, or ethical, decision-making of individuals, Rest’s model distinguishes between four constituents:45 Vozzola, E. C. & Senland, A. K. Moral development. Theory and applications (Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, New York, London, 2022).

- Moral sensitivity defines the individual’s required awareness regarding possible courses of action and their respective consequences including those for other individuals.

- Moral judgement describes the ability to make moral judgements regarding the imagined courses of action. That is, the individual must be able to evaluate which possible decisions are morally right.

- Moral motivation refers to the individual giving priority to morality over other decision-relevant values, e.g., financial gains.

- Moral character defines the required determination, willpower, or courage to follow through and decide for the morally right course of action.

Although Rest’s general model is the most widely used, there is a range of similar models, some of which focus explicitly on the business context.46 Trevino, L. K. Ethical Decision Making in Organizations: A Person-Situation Interactionist Model. The Academy of Management Review 11, 601; 10.2307/258313 (1986). 47 Dubinsky, A. J. & Loken, B. Analyzing ethical decision making in marketing. Journal of Business Research 19, 83–107; 10.1016/0148-2963(89)90001-5 (1989). 48 Ferrell, O. C. & Gresham, L. G. A Contingency Framework for Understanding Ethical Decision Making in Marketing. Journal of Marketing 49, 87; 10.2307/1251618 (1985). 49 Hunt, S. D. & Vitell, S. A General Theory of Marketing Ethics. Journal of Macromarketing 6, 5–16; 10.1177/027614678600600103 (1986).

Issue-Contingent Model and Moral Intensity

In a 1991 article, Jones argues that previously existing models, like Rest’s four component model, had not sufficiently considered the characteristics of the ethical issue at hand, which influenced the moral agent’s decision. In consequence, Jones has extended existing models with his concept of Moral Intensity. Jones defines the moral intensity of a given ethical issue as a construct of six components:36 Jones, T. M. Ethical Decision Making by Individuals in Organizations: An Issue-Contingent Model. The Academy of Management Review 16, 366; 10.2307/258867 (1991).

- The magnitude of consequences describes the overall harm or benefits caused by the act in question, also considering the number of victims or beneficiaries.

- The social consensus is defined by Jones as the degree to which society at large agrees on the evaluation of the proposed act as good or evil.

- The probability of effect refers to how likely it is that the act in question will cause the evaluated harms or benefits. Combined with the magnitude of consequences, the probability allows for risk assessment similar to the expected value approach in rational choice theory.

- Temporal immediacy refers to the time between the moral act or decision and its anticipated negative or positive consequences.

- Proximity in the context of moral intensity is defined by Jones as how near the moral agent feels to the people affected by their decision. This nearness can be of social, cultural, psychological, or physical nature.

- Concentration of effect refers to the number of individuals affected by the ethical decision, where a more concentrated effect means that fewer individuals are affected.

Social Norms Theory

Other models seek to explain how social norms lead to ethical decision-making in a given setting. One of those models is the Model of Social Norm Activation developed by Cristina Bicchieri.37 Bicchieri, C. The grammar of society. The nature and dynamics of social norms (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2006). According to her model, an individual follows a social norm, i.e., abides by the informal rule in a given situation where the social norm is in conflict with other interests, when a set of criteria is met:37 Bicchieri, C. The grammar of society. The nature and dynamics of social norms (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2006). 38 Blay, A. D., Gooden, E. S., Mellon, M. J. & Stevens, D. E. The Usefulness of Social Norm Theory in Empirical Business Ethics Research: A Review and Suggestions for Future Research. Journal of Business Ethics 152, 191–206; 10.1007/s10551-016-3286-4 (2018).

- Contingency requires the individual to know that the norm exists and applies to the situation at hand.

- Conditional preference means, that the individual prefers to follow the norm under the following conditions: a) the individual believes that a sufficiently large portion of society follows the norm in similar situations (empirical expectations) and b) the individual believes that a sufficiently large portion of society expects them to abide by the norm in the situation at hand and may possibly sanction non-conformity (normative expectations). Whether the necessary conditions for following a social norm are met depends on two factors. First, situational cues provide the required information to be consciously or subconsciously processed. Additionally, the model defines individual dispositions referred to as norm sensitivity, that describe the differences in individuals’ empirical and normative expectations, as well as their required thresholds regarding the portion of society that abides by the rule and whether they need to believe that non-conformity may be sanctioned by others.

4.3 Empirical Literature

Ethical decision-making

Over the past decades, hundreds of research articles have dealt with the effects of individual and organizational level factors on ethical decision-making.39 Ford, R. C. & Richardson, W. D. Ethical decision making: A review of the empirical literature. J Bus Ethics 13, 205–221; 10.1007/BF02074820 (1994). 40 Loe, T. W., Ferrell, L. & Mansfield, P. A Review of Empirical Studies Assessing Ethical Decision Making in Business. Journal of Business Ethics 25, 185–204; 10.1023/A:1006083612239 (2000). 41 O’Fallon, M. J. & Butterfield, K. D. A Review of The Empirical Ethical Decision-Making Literature: 1996–2003. J Bus Ethics 59, 375–413; 10.1007/s10551-005-2929-7 (2005). 42 Craft, J. L. A Review of the Empirical Ethical Decision-Making Literature: 2004–2011. Journal of Business Ethics 117, 221–259; 10.1007/s10551-012-1518-9 (2013). 38 Blay, A. D., Gooden, E. S., Mellon, M. J. & Stevens, D. E. The Usefulness of Social Norm Theory in Empirical Business Ethics Research: A Review and Suggestions for Future Research. Journal of Business Ethics 152, 191–206; 10.1007/s10551-016-3286-4 (2018). Particularly since the 1990s, researchers have conducted empirical analyses, focusing on positive models of ethical behavior, such as those of Rest30 Rest, J. R. Moral development. Advances in research and theory (Praeger, New York, N.Y., 1986). and Jones36 Jones, T. M. Ethical Decision Making by Individuals in Organizations: An Issue-Contingent Model. The Academy of Management Review 16, 366; 10.2307/258867 (1991). 38 Blay, A. D., Gooden, E. S., Mellon, M. J. & Stevens, D. E. The Usefulness of Social Norm Theory in Empirical Business Ethics Research: A Review and Suggestions for Future Research. Journal of Business Ethics 152, 191–206; 10.1007/s10551-016-3286-4 (2018). .

The four components from Rest’s model (sensitivity, judgement, motivation, character) typically serve as dependent variables that shall be explained by a range of explanatory variables that describe individual factors (e.g., age, gender, personality, education, culture), organizational factors (e.g., code of conduct, competitiveness, organizational culture, size), as well as measures of the situational moral intensity as defined by the six factors (magnitude of consequences, social consensus, probability of effect, temporal immediacy, proximity, concentration of effect) in the model of Jones36 Jones, T. M. Ethical Decision Making by Individuals in Organizations: An Issue-Contingent Model. The Academy of Management Review 16, 366; 10.2307/258867 (1991). 42 Craft, J. L. A Review of the Empirical Ethical Decision-Making Literature: 2004–2011. Journal of Business Ethics 117, 221–259; 10.1007/s10551-012-1518-9 (2013). .

With a share of 77 %, most studies on ethical decision-making between 2004 and 2011 focus on individual factors while only 17 % investigate the effects of organizational factors.42 Craft, J. L. A Review of the Empirical Ethical Decision-Making Literature: 2004–2011. Journal of Business Ethics 117, 221–259; 10.1007/s10551-012-1518-9 (2013). Table 1 gives an overview of a selection of explanatory variables and key findings:

Table 1 Overview of some empirical findings on ethical decision-making

| Factor | Findings | |

| Individual Factors | Age and Gender Personality Locus of Control Creativity Extraversion, need for affiliation, moral identity Cultural Values | There is much ambiguity in the effects of age or gender on ethical decision-making. 42 Craft, J. L. A Review of the Empirical Ethical Decision-Making Literature: 2004–2011. Journal of Business Ethics 117, 221–259; 10.1007/s10551-012-1518-9 (2013). Internal locus of control is associated with higher moral sensitivity.50 Chan, S. Y. & Leung, P. The effects of accounting students’ ethical reasoning and personal factors on their ethical sensitivity. Managerial Auditing Journal 21, 436–457; 10.1108/02686900610661432 (2006). Creativity is linked to more ethical decisions and more situation specific solution finding.51 Bierly, P. E., Kolodinsky, R. W. & Charette, B. J. Understanding the Complex Relationship Between Creativity and Ethical Ideologies. J Bus Ethics 86, 101–112; 10.1007/s10551-008-9837-6 (2009). Extraversion, low need for affiliation, and strong moral identity are inversely linked to the imitation of unethical behavior.52 O’Fallon, M. J. & Butterfield, K. D. Moral Differentiation: Exploring Boundaries of the “Monkey See, Monkey Do” Perspective. J Bus Ethics 102, 379–399; 10.1007/s10551-011-0820-2 (2011). The results of studies on the effects of cultural values and nationality are generally mixed, although differences between collectivism and individualism appear to play a complex role. 42 Craft, J. L. A Review of the Empirical Ethical Decision-Making Literature: 2004–2011. Journal of Business Ethics 117, 221–259; 10.1007/s10551-012-1518-9 (2013). |

| Organizational Factors | Code of Conduct Organizational and ethical culture Size | The existence of a code of conduct is not linked to higher moral awareness53 Rottig, D., Koufteros, X. & Umphress, E. Formal Infrastructure and Ethical Decision Making: An Empirical Investigation and Implications for Supply Management. Decision Sciences 42, 163–204; 10.1111/j.1540-5915.2010.00305.x (2011). but positively linked to moral judgement54 McKinney, J. A., Emerson, T. L. & Neubert, M. J. The Effects of Ethical Codes on Ethical Perceptions of Actions Toward Stakeholders. J Bus Ethics 97, 505–516; 10.1007/s10551-010-0521-2 (2010). A culture of banal wrongdoing, i.e., unethical business as usual behavior, is generally linked to unethical practices.55 Armstrong, R. W., Williams, R. J. & Barrett, J. D. The Impact of Banality, Risky Shift and Escalating Commitment on Ethical Decision Making. Journal of Business Ethics 53, 365–370; 10.1023/B:BUSI.0000043491.10007.9a (2004). The perceived ethicality of an organization is positively linked to ethical decisions.49 Zhang, J., Chiu, R. & Wei, L. Decision-Making Process of Internal Whistleblowing Behavior in China: Empirical Evidence and Implications. J Bus Ethics 88, 25–41; 10.1007/s10551-008-9831-z (2009). Cultural elements such as ethical norms, standards, practices, incentives, leadership examples, and personal relationships facilitate ethical decision-making.56 Sweeney, B., Arnold, D. & Pierce, B. The Impact of Perceived Ethical Culture of the Firm and Demographic Variables on Auditors’ Ethical Evaluation and Intention to Act Decisions. J Bus Ethics 93, 531–551; 10.1007/s10551-009-0237-3 (2010). 57 Elango, B., Paul, K., Kundu, S. K. & Paudel, S. K. Organizational Ethics, Individual Ethics, and Ethical Intentions in International Decision-Making. J Bus Ethics 97, 543–561; 10.1007/s10551-010-0524-z (2010). 49 Zhang, J., Chiu, R. & Wei, L. Decision-Making Process of Internal Whistleblowing Behavior in China: Empirical Evidence and Implications. J Bus Ethics 88, 25–41; 10.1007/s10551-008-9831-z (2009). 58 Shafer, W. E. & Simmons, R. S. Effects of organizational ethical culture on the ethical decisions of tax practitioners in mainland China. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 24, 647–668; 10.1108/09513571111139139 (2011). 59 Hwang, D., Staley, B., Te Chen, Y. & Lan, J.-S. Confucian culture and whistle‐blowing by professional accountants: an exploratory study. Managerial Auditing Journal 23, 504–526; 10.1108/02686900810875316 (2008). Studies on the effect of organization size on ethical decision-making have come to ambiguous results. 42 Craft, J. L. A Review of the Empirical Ethical Decision-Making Literature: 2004–2011. Journal of Business Ethics 117, 221–259; 10.1007/s10551-012-1518-9 (2013). Although some studies found positive and some negative effects, most analyses could not find evidence for an effect of total organization size at all. 39 Ford, R. C. & Richardson, W. D. Ethical decision making: A review of the empirical literature. J Bus Ethics 13, 205–221; 10.1007/BF02074820 (1994). 40 Loe, T. W., Ferrell, L. & Mansfield, P. A Review of Empirical Studies Assessing Ethical Decision Making in Business. Journal of Business Ethics 25, 185–204; 10.1023/A:1006083612239 (2000). 41 O’Fallon, M. J. & Butterfield, K. D. A Review of The Empirical Ethical Decision-Making Literature: 1996–2003. J Bus Ethics 59, 375–413; 10.1007/s10551-005-2929-7 (2005). 42 Craft, J. L. A Review of the Empirical Ethical Decision-Making Literature: 2004–2011. Journal of Business Ethics 117, 221–259; 10.1007/s10551-012-1518-9 (2013). |

| Situational Moral Intensity | Magnitude of consequences Social consensus Probability of effect Temporal immediacy Proximity Concentration of effect | Moral intensity is found to positively affect moral judgement.54 Karacaer, S., Gohar, R., Aygün, M. & Sayin, C. Effects of Personal Values on Auditor’s Ethical Decisions: A Comparison of Pakistani and Turkish Professional Auditors. J Bus Ethics 88, 53–64; 10.1007/s10551-009-0102-4 (2009). The perceived moral intensity is also found to have a positive effect on moral motivation.60 Valentine, S. R. & Bateman, C. R. The Impact of Ethical Ideologies, Moral Intensity, and Social Context on Sales-Based Ethical Reasoning. J Bus Ethics 102, 155–168; 10.1007/s10551-011-0807-z (2011). 54 Karacaer, S., Gohar, R., Aygün, M. & Sayin, C. Effects of Personal Values on Auditor’s Ethical Decisions: A Comparison of Pakistani and Turkish Professional Auditors. J Bus Ethics 88, 53–64; 10.1007/s10551-009-0102-4 (2009). |

In a more recent article, Blay et al.38 Blay, A. D., Gooden, E. S., Mellon, M. J. & Stevens, D. E. The Usefulness of Social Norm Theory in Empirical Business Ethics Research: A Review and Suggestions for Future Research. Journal of Business Ethics 152, 191–206; 10.1007/s10551-016-3286-4 (2018). propose for future empirical analyses in the field of ethical decision-making to move beyond the four-component framework of Rest and instead draw from social norm theory, specifically Bicchieri’s Model of Social Norm Activation37 Bicchieri, C. The grammar of society. The nature and dynamics of social norms (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2006). .

Other empirical research related to business ethics

A branch of empirical literature seeks to examine the effect of management, strategy, governance, economic cycles, and institutions on corporate social performance (CSP) 56 Mattingly, J. E. Corporate Social Performance: A Review of Empirical Research Examining the Corporation–Society Relationship Using Kinder, Lydenberg, Domini Social Ratings Data. Business & Society 56, 796–839; 10.1177/0007650315585761 (2017). . The concept of CSP focuses on how firms meet their corporate social responsibility with actions. In turn, some studies focus on the effects that CSP has on economic performance, firm reputation, and governance.56 Mattingly, J. E. Corporate Social Performance: A Review of Empirical Research Examining the Corporation–Society Relationship Using Kinder, Lydenberg, Domini Social Ratings Data. Business & Society 56, 796–839; 10.1177/0007650315585761 (2017). 57 Harrison, J. S. & Berman, S. L. Corporate Social Performance and Economic Cycles. Journal of Business Ethics 138, 279–294 (2016). CSP is commonly measured using databases with ESG (environmental, social, governance) ratings originally from the context of sustainable finance and investment. In the past decades, the KLD (Kinder, Lydenberg, and Domini) database, now part of the ESG indexes published by MSCI58 MSCI. MSCI ESG Indexes. Available at https://www.msci.com/our-solutions/indexes/esg-indexes (2023). , has been predominantly used, although more recently other databases like Sustainalytics and Asset4 are increasingly popular among researchers. 59 Harrison, J. S., Yu, X. & Zhang, Z. Consistency among common measures of corporate social and sustainability performance. Journal of Cleaner Production 391, 136232; 10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136232 (2023). KLD ratings, consist of evaluations of firms’ strengths and concerns in categories such as diversity, employee relations, the environment, community, and products 11 Strengths are defined as activities, where firms exceed societal expectations, whereas concerns or weaknesses refer to areas of neglect and violations against CSR expectations. 57 Harrison, J. S. & Berman, S. L. Corporate Social Performance and Economic Cycles. Journal of Business Ethics 138, 279–294 (2016). 61 Mattingly, J. E. Corporate Social Performance: A Review of Empirical Research Examining the Corporation–Society Relationship Using Kinder, Lydenberg, Domini Social Ratings Data. Business & Society 56, 796–839; 10.1177/0007650315585761 (2017). 57 Harrison, J. S. & Berman, S. L. Corporate Social Performance and Economic Cycles. Journal of Business Ethics 138, 279–294 (2016).

Furthermore, there is a branch of literature that focuses on illegal corporate behavior, a matter closely linked to business ethics due to the intersection of law and ethics, where illegal behavior in most cases is seen as unethical. 62 Baucus, M. S. Pressure, opportunity and predisposition: A multivariate model of corporate illegality. Journal of Management 20, 699–721; 10.1016/0149-2063(94)90026-4 (1994). 63 Baucus, M. S. & Baucus, D. A. Paying the piper: an empirical examintation of longer-term financial consequences of illegal corporate behavior. Academy of Management Journal 40, 129–151; 10.2307/257023 (1997). 64 Baucus, M. S. & Near, J. P. Can Illegal Corporate Behavior be Predicted? An Event History Analysis. AMJ 34, 9–36; 10.5465/256300 (1991). 65 McKendall, M. A. & Wagner, J. A. Motive, Opportunity, Choice, and Corporate Illegality. Organization Science 8, 624–647; 10.1287/orsc.8.6.624 (1997). 66 Mishina, Y., Dykes, B. J., Block, E. S. & Pollock, T. G. Why “Good” Firms do Bad Things: The Effects of High Aspirations, High Expectations, and Prominence on the Incidence of Corporate Illegality. AMJ 53, 701–722; 10.5465/amj.2010.52814578 (2010). 67 Nieri, F. & Giuliani, E. International Business and Corporate Wrongdoing: A Review and Research Agenda. In Contemporary Issues in International Business (Palgrave Macmillan, Cham2018), pp. 35–53.

4.4 Avenues for future research

Technological and societal developments continue to bring new aspects and perspectives to the academic field of business ethics. Hence, the core question how and why business and ethics can or cannot go hand in hand is still to be explored from different and new angles. Some contemporary topics and models deal with the intersection of strategy and ethics, the inherent ethicality or unethicality of business models, and the perception of self-belief and risk-taking in entrepreneurship. 18 Dacin, M. T., Harrison, J. S., Hess, D., Killian, S. & Roloff, J. Business Versus Ethics? Thoughts on the Future of Business Ethics. Journal of Business Ethics 180, 863–877; 10.1007/s10551-022-05241-8 (2022).

5. Practical Implementation

Business ethics and their practical implementation have gained significant importance in recent decades due to a remarkable growth of this field, especially in the industrialized countries.68 Demise, N. Business Ethics and Corporate Governance in Japan. Business & Society 44, 211–217; 10.1177/0007650305274914 (2005). 69 van Liedekerke, L. & Dubbink, W. Twenty Years of European Business Ethics – Past Developments and Future Concerns. Journal of Business Ethics 82, 273–280; 10.1007/s10551-008-9886-x (2008). 70 Woermann, M. On the (im)possibility of business ethics. Critical complexity, deconstruction, and implications for understanding the ethics of business (Springer, Dordrecht, 2013). In addition, a general upward trend can also be seen in developing and emerging countries, further underlining the growing attention for this field.71 Xiaohe, L. Business Ethics in China. Journal of Business Ethics 16, 1509–1518; 10.1023/A:1005802812476 (1997). 72 Adeleye, I., Luiz, J., Muthuri, J. & Amaeshi, K. Business Ethics in Africa: The Role of Institutional Context, Social Relevance, and Development Challenges. Journal of Business Ethics 161, 717–729; 10.1007/s10551-019-04338-x (2020). The reasons behind this development are primarily rising prosperity and improved education, coupled with growing general awareness. These main factors, along with a few other developments, are causing society to increase its expectations regarding a company’s integrity. This situation has resulted in a general misalignment between the heightened expectations of business ethics and the ethics that are effectively implemented in practice, leading to the so called “Ethical Problem”. This implies that the level of implemented business ethics, while slowly improving over the last decades, still remains significantly lower than society’s perception of business ethics. 25 Carroll, A. B., Brown, J. A. & Buchholtz, A. K. Business & society. Ethics, sustainability, and stakeholder management (Cengage Learning, Boston, MA, 2018). 73 Robin, D. P. & Reidenbach, R. E. Social Responsibility, Ethics, and Marketing Strategy: Closing the Gap between Concept and Application. Journal of Marketing 51, 44–58; 10.1177/002224298705100104 (1987).

To address this issue, there are several tools available to put business ethics into practice. The selection of these ethical tools must be chosen carefully, given that both the business and ethical environments are characterized by dynamic and complex structures that change frequently. Contextual factors, such as the organizational form or size, the specific history and development of an organization, or the wider sociocultural environment, play a crucial role in shaping the ethical climate. Given these circumstances, while prescribing moral norms may provide compliance, it does not guarantee morally sound behavior, and therefore conflict between ethical certainty and business reality seems inevitable. As a result, ethics may seem incompatible with a management approach that simply adheres to predefined rules. What is important are the dynamic interactions perceived in relation to current local, culture-specific, and industry-specific contexts.72 Morris, M. H., Schindehutte, M., Walton, J. & Allen, J. The Ethical Context of Entrepreneurship: Proposing and Testing a Developmental Framework. Journal of Business Ethics 40, 331–361; 10.1023/A:1020822329030 (2002). 73 Belak, J. & Milfelner, B. Informal and formal institutional measures of business ethics implementation at different stages of enterprise life cycle. Acta Polytechnica Hungarica 8, 105–122 (2011).

For this reason, a variety of instruments and measures exists that can be used to implement business ethics. The effectiveness of these tools varies depending on the situation, and only a select few consistently play a central role to put business ethics into practice. Consequently, the implementation process is accompanied by various barriers that prevent companies from successfully applying business ethics in practice. But at the same time, there are essential drivers that display why attempting to bridge the gap of the ethical problem can be beneficial for a company.

5.1 Tools to implement business ethics

In the following section, selected tools for the implementation of business ethics, which have received increasing attention in literature and research, are listed. These tools serve to establish, optimise, and maintain an ethical corporate culture and at the same time prevent unethical and illegal actions.73 Belak, J. & Milfelner, B. Informal and formal institutional measures of business ethics implementation at different stages of enterprise life cycle. Acta Polytechnica Hungarica 8, 105–122 (2011). 25 Carroll, A. B., Brown, J. A. & Buchholtz, A. K. Business & society. Ethics, sustainability, and stakeholder management (Cengage Learning, Boston, MA, 2018).

Table 2 Tools to implement business ethics

| Tools | Description |

| Board of Directors – Leadership and Supervision | In the corporate context, a firm’s board of directors plays a central role in shaping the (moral) leadership tone of the company, which in turn defines the organisational culture, policies and behavioural expectations towards employees and managers. The board is responsible for overseeing and monitoring management, for monitoring compliance with the code of ethics, and for defining and communicating it – the same applies optionally to a company’s holistic ethics programme, unless the latter is delegated to existing standing committees or an ethics committee. A lack of supervision can encourage unethical behaviour by managers.74 Brink, A. Corporate Governance and Business Ethics (Scholars Portal, Dordrecht, 2011). 75 Pearce, J. A. & Zahra, S. A. The Relative Power of CEOs and Boards of Directors: Associations with Corporate Performance. Strategic Management Journal 12, 135–153 (1991). 76 J. Edward Ketz (ed.). Accounting Ethics: Crisis in accounting ethics (Routledge, London, 2006). The Board can demonstrate its dedication to the ethics program by having Board members oversee the implementation of various initiatives and actions. This could include underlining the importance of the code of ethics by linking executive remuneration (in part) to compliance with the code, reviewing the results of ethics audits, receiving reports on whistle-blowing mechanisms such as ethics hotlines and reviewing the adequacy of resources provided by the organisation for ethics training programs.74 Brink, A. Corporate Governance and Business Ethics (Scholars Portal, Dordrecht, 2011). |

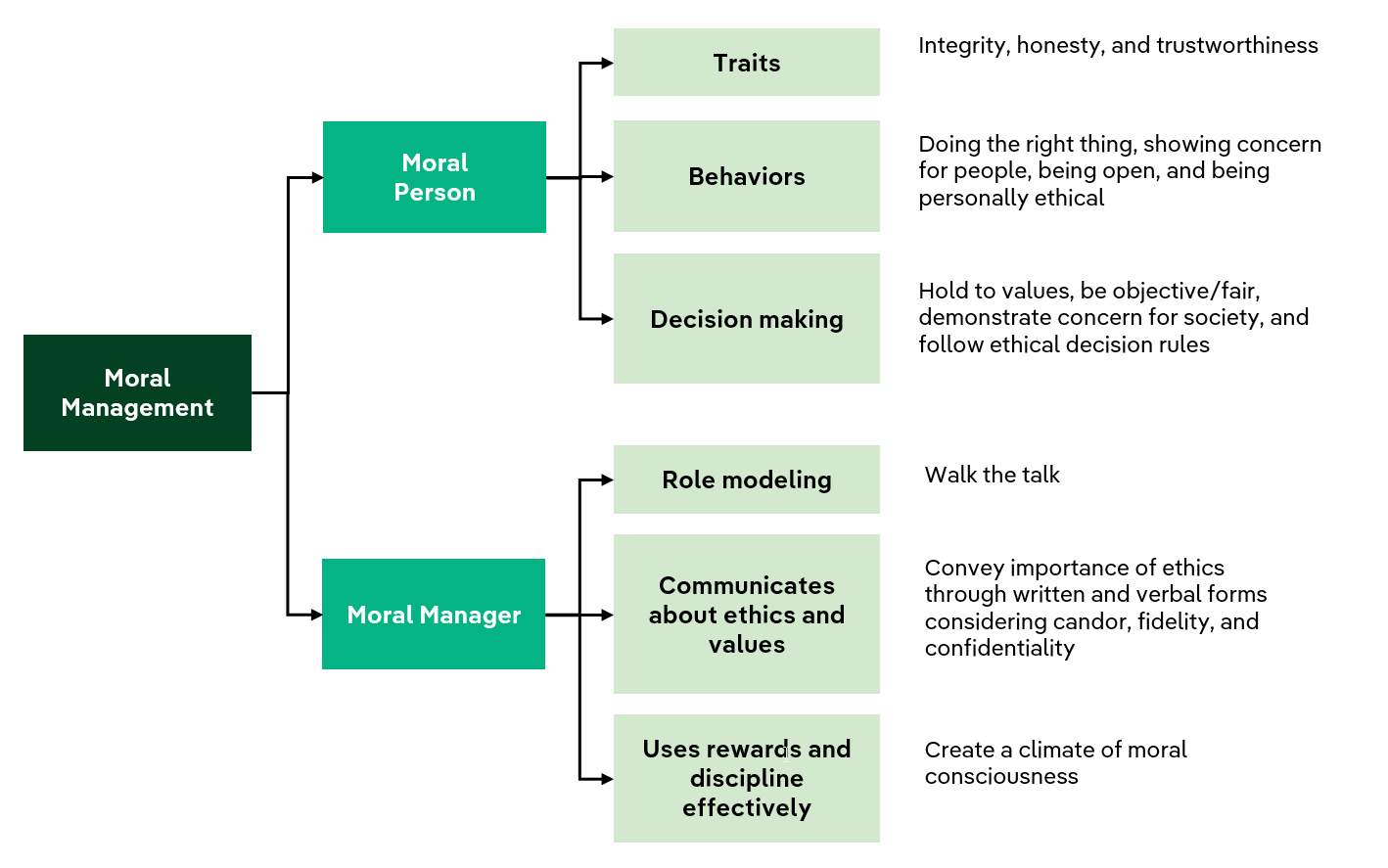

| Moral Management (and effective communication of ethical messages) | The concept of moral management refers to the process in which the moral dimension is the central aspect of the control of an organization. This also includes the successful and effective implementation and the achievement of the organization’s goals. In the process of moral management morality is introduced a priori and incorporates it as a pervasive element in the functioning of the organization, regardless of the level of implementation or the goals pursued by the organization. Here moral refers to a “set of guidelines” for how the organization operates, reflected in all internal processes and systems, “both latent and manifest”.77 Bergoč, J. N. & Mesner-Andolšek, D. Ethical infrastructure. The road to moral management (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne, 2019). Due to the importance of moral management and its central role in the effective communication of ethical messages, it is treated in a differentiated manner subsequent to the table. |

| Ethical Desicion-Making Processes | Central to the management process is the decision-making which should result in ethically best possible solutions, whereby their design confronts managers with the challenge of uncertain consequences and personal influences. The decision-making process ranges from problem definition and analysis, through the identification and evaluation of potential courses of action, to the implementation of the alternative found to be optimal.78 Hosmer, L. T. The ethics of management (Irwin, Homewood, IL, 1987). 25 Carroll, A. B., Brown, J. A. & Buchholtz, A. K. Business & society. Ethics, sustainability, and stakeholder management (Cengage Learning, Boston, MA, 2018). Possible helpful tools are the Ethics Check or the Ethics Quick Test, useful for managers and other organisational members, which include questions to be answered before a decision is made regarding conformity with laws and company policies, fairness and justice, and feelings about the decision-making and its consequences. It should be noted that the responses of these do not provide a definitive ethical judgement, unlike the Ethics Screen method which, inter alia, identifies morally acceptable options.25 Carroll, A. B., Brown, J. A. & Buchholtz, A. K. Business & society. Ethics, sustainability, and stakeholder management (Cengage Learning, Boston, MA, 2018). |

| Realistic Targets | In organisations, the pressure to perform to achieve financial and business targets (combined with time deadlines) can be a driver of unethical behaviour by employees.72 Morris, M. H., Schindehutte, M., Walton, J. & Allen, J. The Ethical Context of Entrepreneurship: Proposing and Testing a Developmental Framework. Journal of Business Ethics 40, 331–361; 10.1023/A:1020822329030 (2002). 79Gerald Nwora, N. & Chinwuba, M. S. Sales Force – Customer Relationship and Ethical Behaviours in the Nigerian Banking Industry: A Synthesis. IOSR JBM 19, 64–72; 10.9790/487X-1901056472 (2017). 80 Tang, T. L.-P. & Chiu, R. K. Income, Money Ethic, Pay Satisfaction, Commitment, and Unethical Behavior: Is the Love of Money the Root of Evil for Hong Kong Employees? Journal of Business Ethics 46, 13–30; 10.1023/A:1024731611490 (2003). This is reinforced by unrealistically set goals and the threat of unpleasant consequences if they are not achieved.81 Baskaran, S., Yang, L. R., Yi, L. X. & Mahadi, N. Ethically Challenged Strategic Management: Conceptualizing Personality, Love for Money and Unmet Goals. IJARBSS 8; 10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i4/4015 (2018). It is therefore crucial that managers set clear and achievable goals and check how the results – costs as well as profits – have been achieved.82 Murphy, P. E. Implementing Business Ethics. Journal of Business Ethics 7, 907–915 (1988). |

| Ethics and Compliance Programs (and Officers) | The successful achievement of ethical goals – such as establishing high standards of integrity and a responsible reputation, reinforcing the company’s code of ethics, mitigating and disclosing corporate misconduct – depends significantly on the implementation of effective ethics and compliance programs.83 Team, E. Global Business Ethics Survey. Ethics and Compliance Initiative (2020). 84 OECD. Recommendation of the Council on Principles of Corporate Governance. Available at https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0413#backgroundInformation (2023). High-quality programs can reduce misconduct by up to 66%, increase its reporting to management by up to 88%, and provide the company with a competitive advantage through trustworthiness and effective results, in addition to reducing costs.85 Ethics & Compliance Initiative. Principles and Practices of High Quality Ethics & Compliance Programs. Report of ECI’s Blue Ribbon Panel, 2016. The Ethics & Compliance Initiative (ECI) generalises various characteristics that make up successful ethics and compliance programs. According to it, ethics and compliance should be a key pillar of the business strategy and risks in this area should be identified and reduced. Managers should further establish a culture of integrity at all levels of the hierarchy. Ultimately, reporting of alleged misconduct and concerns should be supported and valued, and misconduct should be responded to appropriately.85 Ethics & Compliance Initiative. Principles and Practices of High Quality Ethics & Compliance Programs. Report of ECI’s Blue Ribbon Panel, 2016. Programme quality, the strength of the ethical workplace culture and the impact of the programs are interrelated.86 Ethics & Compliance Initiative. Global Business Ethics Survey Report. The State of Ethics & Compliance in the Workplace. Differences Between Small, Medium and Large Enterprises, 2022. Responsibility for ethics and compliance programs and related initiatives usually rests with ethics or compliance officers who report to the top management level – in the US, reporting to the board is regulated by law.87 Weber, J. & Wasieleski, D. M. Corporate Ethics and Compliance Programs: A Report, Analysis and Critique. Journal of Business Ethics 112, 609–626; 10.1007/s10551-012-1561-6 (2013). Some key elements and measures of ethics and compliance programs – the Code of Ethics or Conduct, the Sanction and reward system, Whistle Blowing Mechanisms/Ethical Hotlines, Ethics Training Programs, Ethics Audits (and Risk Assessments) – are explained subsequently. |

| Code of Ethics or Conduct | The code of ethics, also called code of conduct,88 Wulf, K. From codes of conduct to ethics and compliance programs. Recent developments in the United States (Logos Verlag, Berlin, 2011). has established itself internationally as one of the most recognised and fundamental methods for realising and promoting an ethical corporate culture. As a central component of ethics and compliance programs, it acts as a guide for the behaviour of organisational members by providing ethical behaviour guidelines.25 Carroll, A. B., Brown, J. A. & Buchholtz, A. K. Business & society. Ethics, sustainability, and stakeholder management (Cengage Learning, Boston, MA, 2018). 88 Wulf, K. From codes of conduct to ethics and compliance programs. Recent developments in the United States (Logos Verlag, Berlin, 2011). 73 Belak, J. & Milfelner, B. Informal and formal institutional measures of business ethics implementation at different stages of enterprise life cycle. Acta Polytechnica Hungarica 8, 105–122 (2011). In the US, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (Section 406) makes disclosure of the company’s code of ethics – which, according to the Act, should primarily provide guidelines for ethical and honest conduct and promote compliance with government rules and regulations – a legal requirement, and any absence of it must be justified.89 Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, Pub. L. No. 107-204, § 406, 116 Stat. 745 (2002). Due to the high relevance of this instrument in the context of the implementation and preservation of business ethics in an organisation, the code of ethics will be discussed in more detail below. |

| Sanction and reward system | In line with the corporate values, organisations shall respond promptly, consistently, transparently, and responsibly to any confirmed violations of the core ethical values. Communicating misconduct internally and, where appropriate, externally and sanctioning it underscores that unethical behaviour will not be tolerated. This ensures the respect of the organisation’s members and prevents and reduces misconduct. The sanctions – which are a factor that strengthens the corporate culture – should depend on the severity of the violation, regardless of the status of the person, be communicated within the organisation and be defined in the code of ethics. To the same extent, incentives must be actively created for employees to behave in accordance with ethical corporate principles through rewards.90 Murphy, P. E. Eighty exemplary ethics statements (University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame, Ind, 2002). 85 Ethics & Compliance Initiative. Principles and Practices of High Quality Ethics & Compliance Programs. Report of ECI’s Blue Ribbon Panel, 2016. 86 Ethics & Compliance Initiative. Global Business Ethics Survey Report. The State of Ethics & Compliance in the Workplace. Differences Between Small, Medium and Large Enterprises, 2022. |

| (Anonymous) whistle-blowing mechanisms/ Ethics Hotlines and protection mechanisms | In order for observed violations to be adequately addressed, the establishment of a confidential or anonymous system to facilitate their reporting, as well as protection mechanisms for whistle blowers, are of great importance. The preferred hotlines for the reporting of suspicious cases are email reporting, web-based reporting systems and telephone hotlines. As cues and concerns are occasionally communicated to organisational members through face-to-face interaction, it is essential that any employees are informed on how to act in such a situation. The implementation of a whistleblowing policy underlines management’s active advocacy for individuals to report questionable practices.84 OECD. Recommendation of the Council on Principles of Corporate Governance. Available at https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0413#backgroundInformation (2023). 91 ACFE. Occupational Fraud 2022: A Report to the nations, 2022. 86 Ethics & Compliance Initiative. Global Business Ethics Survey Report. The State of Ethics & Compliance in the Workplace. Differences Between Small, Medium and Large Enterprises, 2022 |

| Ethics Training Programs | Ethics training programs are a common tool in companies to teach business ethics to executives, board members, managers and employees, to promote ethical competencies and to prevent unethical behaviour. They support in identifying ethical challenges in the workplace, becoming aware of the tools available to address them, as well as dealing with dilemmas appropriately, and are usually guided by an internal trainer or staff member.86 Ethics & Compliance Initiative. Global Business Ethics Survey Report. The State of Ethics & Compliance in the Workplace. Differences Between Small, Medium and Large Enterprises, 2022 87 Weber, J. & Wasieleski, D. M. Corporate Ethics and Compliance Programs: A Report, Analysis and Critique. Journal of Business Ethics 112, 609–626; 10.1007/s10551-012-1561-6 (2013). 92 Kreismann, D. & Talaulicar, T. Business Ethics Training in Human Resource Development: A Literature Review. Human Resource Development Review 20, 68–105; 10.1177/1534484320983533 (2021). According to research, ethics programs have positive outcomes on participants’ moral development and ethical behaviour. Usually, more than two different training methods are used, including active learning (e.g. through interaction, discussion), communication of the code of ethics or computer-based training programs. For the programs to be effective, regular repetitions, reflection time and preferably longer training durations (e.g. approx. 10 weeks) are necessary. The implementation of such programs also signals that the top management supports ethical behaviour as well as efforts to make appropriate decisions in moral dilemmas. 92 Kreismann, D. & Talaulicar, T. Business Ethics Training in Human Resource Development: A Literature Review. Human Resource Development Review 20, 68–105; 10.1177/1534484320983533 (2021). 93 Steele, L. M. et al. How do we know what works? A Review and Critique of Current Practices in Ethics Training Evaluation. Accountability in research 23, 319–350; 10.1080/08989621.2016.1186547 (2016). 94 Delaney, J. T. & Sockell, D. Do Company Ethics Training Programs Make a Difference? An Empirical Analysis. Journal of Business Ethics 11, 719–727 (1992). 87 Weber, J. & Wasieleski, D. M. Corporate Ethics and Compliance Programs: A Report, Analysis and Critique. Journal of Business Ethics 112, 609–626; 10.1007/s10551-012-1561-6 (2013). |

| Ethics Audits | The assessment and review of the ethics and compliance programme, existing procedures, and policies as well as the moral commitment of an organisation is done by means of Ethics Audits. These can be undertaken by external audit organisations or internally – for example, through employee surveys, interviews (e.g. with the audit committee) or written instruments. Ethics audits provide insights into the state of development of the company, the fulfilment of ethical obligations, the perception of the working climate, factors that favour unethical behaviour or ethical abuses as well as findings on optimisation potential.95 Metzger, M., Dalton, D. R. & Hill, J. W. The Organization of Ethics and the Ethics of Organizations: The Case for Expanded Organizational Ethics Audits. Bus. Ethics Q. 3, 27–44; 10.2307/3857380 (1993). 96 García-Marzá, D. From ethical codes to ethical auditing: An ethical infrastructure for social responsibility communication. Ética, investigación y comunicación 26, 268; 10.3145/epi.2017.mar.13 (2017). |

| Risk Assessments | Another controlling ethics initiative in companies is the internal (Fraud) Risk Assessment, which is mainly used to identify concerns, fraudulent activities, and potential problem areas at an early stage and to control and evaluate the effectiveness of reporting systems implemented in organisations. It is intended to help combat fraud and act in accordance with legal requirements. The frequency of risk assessment varies between organisations and is carried out either by the audit department, the ethics department or ethics officer, or the legal department.87 Weber, J. & Wasieleski, D. M. Corporate Ethics and Compliance Programs: A Report, Analysis and Critique. Journal of Business Ethics 112, 609–626; 10.1007/s10551-012-1561-6 (2013). 97 Vice Vicente. SOX Compliance Requirements & Overview. Available at https://www.auditboard.com/blog/sox-compliance/ (2023). |

| Corporate Transparency | Corporate transparency refers to the deliberate disclosure of information by organisations about, inter alia, their business activities, data, intentions, and behaviour. The decision on internal and public levels of transparency depends on legal, ethical, and business factors. Disclosure may be provided in the form of standardised documents or by means of communication and information technologies. Internally, (management) transparency contributes significantly to the positive influence of employee satisfaction, motivation, and commitment. Externally, it allows stakeholders and other potential users to check whether the company complies with ethical standards and legal requirements. This reduces uncertainty about the behaviour and results of a company, prevents unethical behaviour on the part of management and promotes moral behaviour.98 Thommen, J.-P. et al. Allgemeine Betriebswirtschaftslehre. Umfassende Einführung aus managementorientierter Sicht (Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden, 2020). 99 Lipman, V. New Study Shows Transparency Isn’t Just Good Ethics – It’s Good Business. Forbes (2013). 100 Turilli, M. & Floridi, L. The ethics of information transparency. Ethics Inf Technol 11, 105–112; 10.1007/s10676-009-9187-9 (2009). 101 das Neves, J. C. & Vaccaro, A. Corporate Transparency: A Perspective from Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologiae. Journal of Business Ethics 113, 639–648; 10.1007/s10551-013-1682-6 (2013). |

5.2 Moral Management and effective communication of ethical messages

A manager can be said to be ethical if he or she demonstrates “normatively appropriate conduct” (such as fairness or honesty) in his or her own actions and social relationships and promotes this behaviour to his or her followers through communication, decision-making and reinforcement (including setting ethical standards, rewarding compliance and punishing violations).102 Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K. & Harrison, D. A. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 97, 117–134; 10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.002 (2005). The effectiveness of moral managers is reflected in their perception by employees and external stakeholders and is reinforced by character traits such as trustworthiness, honesty and integrity and behaviours such as “Being Open”, “Concern for People”, “Do the Right Thing” and “Personal Morality”.103 Treviño, L. K., Hartman, L. P. & Brown, M. Moral Person and Moral Manager: How Executives Develop a Reputation for Ethical Leadership. California Management Review 42, 128–142; 10.2307/41166057 (2000). As decision-makers, they should practice fair, objective decision-making, adhere to their ethical values in their decisions and pursuit of success, and operate within the framework of ethical principles and legal principles as well as take society into account.102 Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K. & Harrison, D. A. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 97, 117–134; 10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.002 (2005). 103 Treviño, L. K., Hartman, L. P. & Brown, M. Moral Person and Moral Manager: How Executives Develop a Reputation for Ethical Leadership. California Management Review 42, 128–142; 10.2307/41166057 (2000). 104 Carroll, A. B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons 34, 39–48; 10.1016/0007-6813(91)90005-G (1991).

Managers play an important role in how organisational members should act and work in the company through personal example and shaping official and unspoken policies.105 Sims, R. R. & Quatro, S. A. (eds.). Leadership. Succeeding in the Private, Public, and Not-for-profit Sectors (M.E.Sharpe, Armonk, N.Y, 2005). Moral managers thus assume a leadership and role model function in ethical matters within the organisation,104 Carroll, A. B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons 34, 39–48; 10.1016/0007-6813(91)90005-G (1991). as well as a central position in communicating corporate values and ethics.103 Treviño, L. K., Hartman, L. P. & Brown, M. Moral Person and Moral Manager: How Executives Develop a Reputation for Ethical Leadership. California Management Review 42, 128–142; 10.2307/41166057 (2000). They have to operate in the knowledge that their actions are visible to, observed and analysed by employees. They shall convey an effective ethical message and implement various aspects of organisational action that (guide employees and) are conducive to the maintenance of ethical behaviour.103 Treviño, L. K., Hartman, L. P. & Brown, M. Moral Person and Moral Manager: How Executives Develop a Reputation for Ethical Leadership. California Management Review 42, 128–142; 10.2307/41166057 (2000). 106 Mayer, D. M., Kuenzi, M. & Greenbaum, R. L. Examining the Link Between Ethical Leadership and Employee Misconduct: The Mediating Role of Ethical Climate. Journal of Business Ethics 95, 7–16; 10.1007/s10551-011-0794-0 (2010). Basic values and ethics guiding action and decision-making must be communicated regularly by morally oriented leaders in an explanatory manner to convey their relevance, and rewards must be used for desirable ethical behaviour according to specific rules and norms, as well as discipline for rule-breaking, to reinforce the former and mitigate undesirable behaviour.103 Treviño, L. K., Hartman, L. P. & Brown, M. Moral Person and Moral Manager: How Executives Develop a Reputation for Ethical Leadership. California Management Review 42, 128–142; 10.2307/41166057 (2000). Numerous studies show that the climate of an organization emerges significantly from behaviours and policies emphasized and practiced by managers and, consequently, can be effectively modified through leadership.106 Mayer, D. M., Kuenzi, M. & Greenbaum, R. L. Examining the Link Between Ethical Leadership and Employee Misconduct: The Mediating Role of Ethical Climate. Journal of Business Ethics 95, 7–16; 10.1007/s10551-011-0794-0 (2010). 107 Stringer, R. Leadership and organizational climate. The cloud chamber effect (Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2002). Based on existing literature, Schwartz (2013) identifies “the continuous presence of ethical leadership” as one of three necessary core factors for building and sustaining an ethical corporate culture, which should be apparent as an appropriate ethical standard across managers, senior executives and the board of directors.108 Schwartz, M. S. Developing and sustaining an ethical corporate culture: The core elements. Business Horizons 56, 39–50; 10.1016/j.bushor.2012.09.002 (2013).

Good Practice Examples

A strong example of moral management is James Burke’s work at Johnson & Johnson (J&J) from 1975 onwards. He initiated an internal dialogue on the moral basis of the company immediately after his appointment as Chairman and CEO by questioning and discussing with top management the relevance and significance of the contents of the J&J credo, which at that time had already existed for three decades. Right at the beginning of his tenure, he thus made a clearly communicated, formative and visible moral statement. His strategy was to gain and maintain trust based on moral behaviour, building on the institutional trust already generated by his predecessors. In the wake of poisoning incidents from one of the marketed products (Tylenol) during his time at J&J, Burke responded in an engaged, transparent, and candid manner, including being fully responsive to reporters and consumers. The product was withdrawn from circulation and tamper-proofed in cooperation with the federal government and state agencies before being reintroduced. Despite the incidents, the company and brand continued to be perceived positively by consumers. Following further cases of poisoning a few years later, Burke again publicly communicated the company’s stance on the situation and withdrew the product from the market, which J&J could not guarantee was safe. Considering the situation, he initiated an internal survey of all employees regarding their assessment of the company’s performance in the context of the mission statement, in combination with a subsequent dialogue between managers and employees. Based on the results obtained, action plans for solving emerging problems were developed. Throughout his entire tenure, James Burke maintained his moral integrity and acted in an exemplary manner consistent with the articulated credo of the company. He firmly integrated these principles into the structure of the company’s culture, anchored them in the individual’s consciousness, and thereby strengthened trust in J&J’s products and the company itself.109 Murphy, P. E. & Enderle, G. Managerial Ethical Leadership: Examples Do Matter. Business Ethics Quarterly 5, 117–128; 10.2307/3857275 (1995). 103 Treviño, L. K., Hartman, L. P. & Brown, M. Moral Person and Moral Manager: How Executives Develop a Reputation for Ethical Leadership. California Management Review 42, 128–142; 10.2307/41166057 (2000).

Challenges