Authors: Victoria Eichler, Leonie Hein, Timo Mettjes, Nicolas Nold

Edited by: Hannah Dahmen, Marco Dorow, Rebecca Katharina Hillebrandt, Mareike Ropers, Carola Coninx, Lina Hansen, Lukas Heitmann, Maja Roos, Niklas Wölfer

Last updated: January 03, 2023

1 Definition and relevance

At present, there is no generally applicable definition of sustainability. Especially in various concepts, very different definitions are used. The relevance of an unanimous definition is particularly noticeable in sustainability accounting and reporting.

Sustainability accounting and reporting have the potential to enable an effective accountability system. In particular, risk management and decision-making imperatives come into play through implementation. Sustainability reporting offers many benefits to corporate management in decision making, planning and execution. Awareness of sustainability issues is increased.

Reporting practices in general have undergone drastic changes throughout the centuries. Starting in the industrial revolution, at the beginning of the 19th century, companies were pushed to report about social matters, work conditions, and the education of employees as well as work safety policies.1 Nikolina Markota Vukić, R. Vukovic & Donato Calace (2018). Non-financial reporting as a new trend in sustainability accounting. The Journal of Accounting and Management), 13–26. In the 1970s, social components were included in financial reports for the first time, and, 10 years later, environmental aspects were also considered.2 Dienes, D., Sassen, R. & Fischer, J. (2016). What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. SAMPJ, 7 (2), 154–189. Starting in the 1980s, social and environmental topics overlapped; thus, social and environmental accounting were sometimes put together, creating the term SEA.3 Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge. Social accounting is seen as an extension of accounting reports that includes information regarding the work environment, the social impact of production, and community activities.4 Mathews, M. R. (1995). Social and Environmental Accounting: A Practical Demonstration of Ethical Concern? Journal of Business Ethics, 14 (8), 663. Social accounting deals with a variety of different issues and is under constant change. Therefore, approaches must be monitored and adapted to the dynamic environment. Despite hostility in the past decades, social accounting has greatly influenced the law and companies in the Anglo-Saxon sphere.5 Gray, R. (2001). Thirty years of social accounting, reporting and auditing: what (if anything) have we learnt? Bus Ethics Eur Rev, 10 (1), 9–15. Environmental accounting aims to disclose environmental-related costs in order to make a quantitative assessment of the environmental impact of certain actions. Furthermore, environmental accounting informs stakeholders about the environmental performance and dedication of companies.6 Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge.

In the course of time, companies found themselves in highly complex and dynamic environments. The SEA approach could not address all the problems; therefore, integrated reports were created.7 Man, M. & Bogeanu-Popa, M.-M. (2020). Impact of Non-Financial Information on Sustainable Reporting of Organisations’ Performance: Case Study on the Companies Listed on the Bucharest Stock Exchange. Sustainability, 12 (6), 2179. Compared to those of sustainability reporting, the objectives of integrated reporting are much broader. It is not simply a reporting tool but, rather, an instrument to approach management decisions in a holistic way (so-called integrated thinking).8 Dienes, D., Sassen, R. & Fischer, J. (2016). What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. SAMPJ, 7 (2), 154–189. The goal is also to integrate sustainability issues successfully into the main financial report rather than as a separate report, without a loss of readability and while keeping the material aspect of both worlds in focus.9 Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). About us. Retrieved on 09/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/about/.

2 International reporting standards and frameworks

Over the years, different international tools have been developed as well as country-specific legislation. In the following, the most well-known and used tools are described. For more possibilities, the ESG Ecosystem Map can be helpful in finding not only more information to implement sustainability reporting but also general information about ESG matters. It is important to consider not only that the following standards and frameworks are different in their content (see Table 2) but also that there are differences between standards and frameworks in general. While standards provide specific and clear instructions for implementation, frameworks offer more general guidance for the preparation of sustainability reporting and accounting. Equally important to acknowledge is that standards can make frameworks workable and can therefore be complementary. 10 Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (2021). Our mission and history. Retrieved on 31/07/21: https://www.globalreporting.org/about-gri/mission-history/. In this regard, the following standards and frameworks may also be used together and complement one another, also throughout partnerships (more on GRIs and key performance indicators). 11 Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). About us. Retrieved on 09/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/about/.

| Name | Description | Website |

| Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) | Standard with a focus on stakeholder engagement and material ESG topics and their impact | https://www.globalreporting.org/ |

| Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) | Standard tailored to investors’ needs and interests regarding industry-specific sustainability topics | https://www.sasb.org/ |

| AccountAbility (AA) | Framework with the aim of building a stronger integration of stakeholders into the sustainability process in an organization | https://www.accountability.org/ |

| ISO 26000 | Standard that offers guidance regarding social responsibility issues and stakeholder engagement | https://www.iso.org/iso-26000-social-responsibility.html |

| European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) | Europäische Standards für die zukünftige Nachhaltigkeitsberichterstattung nach CSRD | Due Process Procedures for Sustainability Reporting Standard-Setting – EFRAG |

2.1 Global Reporting Initiative

As a result of the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1997, the GRI was founded with the aim of providing one of the first accountability mechanisms to hold companies accountable for environment issues, and it was later adjusted to ESG topics. The first version was published in 2000 as a guideline, and, over the years, it was remastered until 2016, when the GRI published the first global standard for sustainability reporting.13 Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (2021). Our mission and history. Retrieved on 31/07/21: https://www.globalreporting.org/about-gri/mission-history. Today, the GRI is seen as one of the more implemented sustainability reporting standards and is updated steadily.14 Daizy, Mitali Sen & N. Das (2013). Corporate Sustainability Reporting: A Review of Initiatives and Trends. The IUP Journal of Accounting Research and Audit Practices), 7–18.

Its standards, in total 41 documents, are available in 12 languages through open access and consist of one universal standard and several topic standards to meet companies’ and stakeholders’ interests and focus on material topics. The universal standard is referred to as GRI 100 and is split into three components. Starting point and foundation for the use of the standard is the GRI and its containing interpretation of the standard as well. The second component, GRI 102 (General Disclosures), contains contextual information about an organization and its sustainability reporting process. Lastly, GRI 103 (Management Approach) should be used together with the topic standards. In addition, the topic-specific standards are divided into three components following the TBL. Economic topics are described in the GRI 200 standard while GRI 300 focuses on environmental issues and GRI 400 on social subjects (more insights on GRIs and key performance indicators).15 Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (2021). Download the standards. Retrieved on 03/08/21: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/download-the-standards.

Besides the open-access standards, the GRI provides different services, tools, and workshops to help companies through every stage of their sustainability reporting process. One possibility is to use one or more of its five services, which can be obtained for a fee. The Content Index Service focuses on improving the usability of the information in the report and creating a clear, understandable content index. The core aim of the second service, the Materiality Disclosure Service, is to improve the presentation of the materiality disclosure. More precisely, the aim is to ensure that the materiality assessment is clear, visible, and reflects the quality of the reporting. Another service GRI offers is the Management Approach Disclosures Service, by which it helps to ensure that the management approach is linked to the material topics to create a more user-friendly presentation. Next, the SDG Mapping Service provides an accurate representation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (more on SDGs linked to key performance indicators). Lastly, the GRI Kickstarter workshop is a service for starting the GRI reporting process.16 Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (2021). Services. Retrieved on 04/08/21: https://www.globalreporting.org/reporting-support/services.

2.2 Sustainability Accounting Standards Board

Sustainability issues in the financial world are becoming more important to stakeholders, including investors, and the demand for clear and transparent information about those issues has increased in almost all branches of the global economy. As a reaction, the SASB was founded as a nonprofit organization to strengthen and clarify the communication between companies and investors about sustainability topics. Now, the SASB standards focus on material sustainability aspects (in connection with ESG issues) for the investors of a company and are available for 77 different industry branches. Because of the growing demand for sustainability reporting standards and frameworks, the SASB decided to join the Value Reporting Foundation in June 2021. Together with the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC), they provide the Integrated Reporting Framework and SASB standards, including Integrated Thinking. The aim of the Integrated Reporting Framework is to enhance the reporting process and integrate sustainability into financial reporting rather than providing it as a separate report (more at https://www.valuereportingfoundation.org/).17 Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). About us. Retrieved on 09/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/about.

The standards are free to download, and, to help identify financially material issues for each industry, the SASB created an interactive tool named the Materiality Map with direct references to the standards and their pages. Besides that, there are two supplements that can be added to the industry-specific standards: Greenhouse Gas Emissions and the Human Capital Bulletin.18 Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). Materiality Map. Retrieved on 11/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/standards/materiality-map. Moreover, the SASB offers information for companies as well as investors, academics, and companies that are interested in licensing SASB for commercial purposes. With a focus on services for companies, the SASB offers a guide to find the right industry in the first place, called the Sustainable Industry Classification System (SCIS). The SCIS differs from other classification systems in the fact that it uses sustainability profiles and not sources of revenue to form industries and sectors like most major industry classification systems.19 Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). Find your industry. Retrieved on 13/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/find-your-industry. After the right industry is found through the SICS and material aspects are identified through the Materiality Map, the Implementation Primer helps companies implement the SASB standards; it is available through open access in five languages.20 Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). Implementation Primer. Retrieved on 13/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/implementation-primer. Another feature, currently in planning, will make the SASB standards available in XBRL, a program in which reports can be generated, with the aim of making the reporting process more efficient. In the meantime, in 2020, the SASB and PwC developed a Draft Taxonomy, and the program as well as guidance is available to help companies implement the SASB standards; it is available through open access in five languages.21 Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). Structured Reporting Using XBRL. Retrieved on 20/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/structured-reporting-xbrl. Last but not least, the SASB offers a database of sustainability reports from various companies in different industry branches to help companies find an example for their own SASB sustainability reports.22 Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). Companies Reporting with SASB Standards. Retrieved on 20/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/company-use/sasb-reporters

Besides the different guides to implementing the SASB standards, it is possible to join a membership called the SASB Alliance. Anyone, individuals as well as companies, can obtain membership for a fee. The membership includes regular newsletters and insights as well as a webinar about sustainability accounting. Also, connecting and exchange with other SASB users is possible, and discounts for several services and meetings are included.23 Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). Alliance Membership. Retrieved on 20/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/alliance-membership

2.3 Integrated Reporting and integrated thinking

Integrated Reporting (IR) is a comprehensive concept that takes into account non-financial reporting elements in addition to traditional financial reporting. This is to be captured by companies in a single report which is not only based on a reporting process but rather on a process characterized by integrated thinking.24Cortese, Rubino in Cinquini, De Luca, Non-financial Disclosure and Integrated Reporting., p. 253 Integrated thinking is understood as taking into account the relationships between the various operating and functional units of a company as well as the relevant capital resources. It thus leads to integrated decision-making and management that has the ability to generate value in short, medium and long term.

According to the Integrated Reporting Framework, IR is defined as ‘a process founded on integrated thinking that results in a periodic integrated report by an organization about value creation over time and related communications regarding aspects of value creation.’25Transition to integrated reporting, IR Framework, September 2021., p. 5

The integrated report is therefore the result of integrated reporting and is a useful source of information for a wide range of groups interested in a company’s ability to create value. These may include customers, suppliers, regulators, policymakers and legislators, but also providers of financial capital. By concisely communicating the value creation process of an organization’s strategy, governance, performance and prospects in the context of its external environment, recipients benefit from full disclosure that does not merely aggregate the individual data of individual reports.26Transition to integrated reporting, IR Framework, September 2021., p. 5 As can be seen, the central guiding principle of IR is the connectivity of information, whereby the various connections and interdependencies between the individual components within an organization lead to the desired value creation process.27Cortese, Rubino in Cinquini, De Luca, Non-financial Disclosure and Integrated Reporting., p. 253

2.4 AccountAbility

AccountAbility (AA) is a global consulting and standards firm that was founded in 1995 with the aim of guiding and supporting different organizations in implementing ESG matters in their practices. Besides its framework, the AA1000 Series of Standards, it offers different services.28 AccountAbility (AA) (2021). About us. Retrieved on 21/08/21: https://www.accountability.org/about The framework is based on four principles: inclusivity, materiality, responsiveness and impact. Inclusivity is focused on the participation in decision-making of stakeholders while materiality is about the material matters of an organization and their clear display. Responsiveness reflects organizations’ need to be transparent about their material sustainability matters and their impact. Lastly, impact ensures that organizations monitor and are held accountable for their business practices. 29 AccountAbility (AA) (2021). Standards. Retrieved on 21/08/21: https://www.accountability.org/standards

The AA1000 Series of Standards framework is available as open access downloads in over 10 languages and is split into three parts. With a focus on developing and implementing sustainability initiatives, the foundation of the AA1000 Series is the AA1000AP (AccountAbility Principles). The second part is the AA1000SES (AA1000 AccountAbility Stakeholder Engagement Standard), which emphasizes stakeholder engagement and how to integrate stakeholders into the business process of an organization. Lastly, the AA100AS v3 (AA1000 Assurance Standard) provides implementation of overall sustainability management and focuses on the readability of sustainability reports.30AccountAbility (AA) (2021). Standards. Retrieved on 21/08/21: https://www.accountability.org/standards

Additionally, AA offers a broad range of services for a fee. The first service, Strategy Design & Implementation, helps organizations develop an ESG strategy for the long run while Governance & Investor Relations provides guidance on governance issues as well as support in investor relations. Another service, Stakeholder Engagement, focuses on matters ranging from the identification of stakeholders to the whole process of actively integrating stakeholders into business practices. Next, the Materiality Review ensures that the most relevant sustainability topics are correctly identified and clearly formulated, considering the impact the organization has within those topics. On the other side, the Impact Assessment deals with key performance indicators (KPIs) and other quantitative and qualitive measurements to express the impact of the organization on ESG issues. To improve communication and readability throughout the reporting process, AA offers the service Reporting & Communication. Lastly, AA also offers a service to implement the frameworks and standards as well as a Training & Capacity Building service with different workshops, modules, and certifications. 31 AccountAbility (AA) (2021). Advisory. Retrieved on 21/08/21: https://www.accountability.org/advisory

2.5 ISO 26000

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) is an independent international organization based in Geneva (Switzerland) that, in cooperation with its global members and using their knowledge, develops international standards in several different areas.32 International Organization for Standardization (ISO) (2021). About us. Retrieved on 22/08/21: https://www.iso.org/about-us.html

ISO26000, or Guidance on Social Responsibility (status: 2010) is a standard that offers guidance regarding social responsibility issues and stakeholder engagement for organizations and describes how to implement ESG matters into an organization’s practices. Mentionable is that ISO explicitly points out that ISO26000 is seen only as a guidance and not as a certification, unlike other ISO management standards. The standard is available for a fee and is designed for different types of organization, no matter the size or industry. To help to implement the standard, ISO issued IAW 26 in 2017 and provides guidance to build a management system using ISO26000. Besides that, it offers training materials in the form of a PowerPoint as well as a training protocol and documents for ISO 26000.33 International Organization for Standardization (ISO) (2021). ISO 26000. Retrieved on 22/08/21: https://www.iso.org/iso-26000-social-responsibility.html

2.6 European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS)

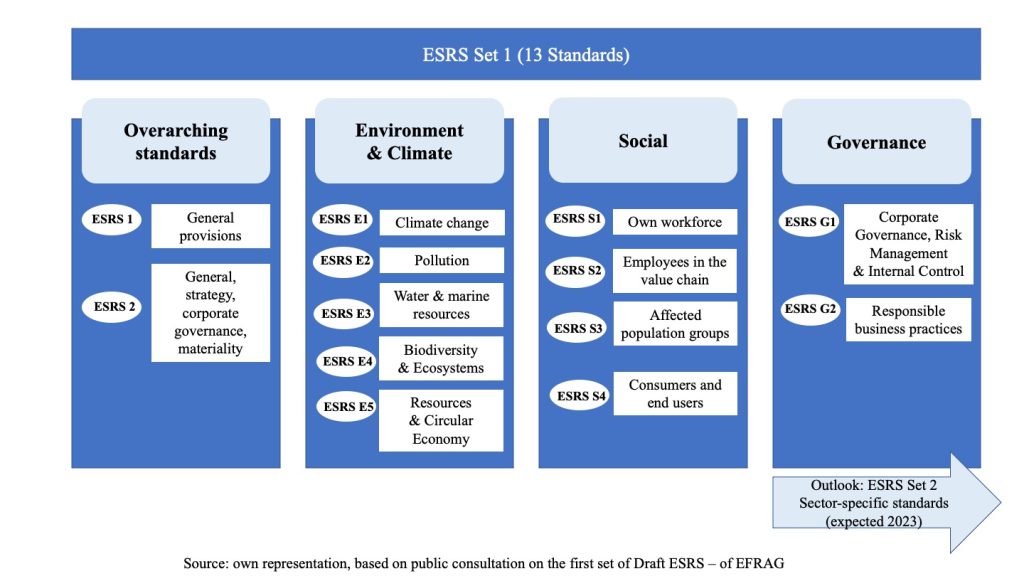

For the uniform implementation of the requirements of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) is working on the development of uniform European sustainability reporting standards (ESRS), which define the content of future sustainability reporting. 34EFRAG, “Due process procedures for sustainability reporting standard-setting,” [Online]. Available: https://www.efrag.org/Activities/2106151549247651/Due-Process-Procedures-for-Sustainability-Reporting-Standard-Setting-. [Accessed 07 09 2022]. The focus is on establishing a connection between goals, measures and performance indicators with an environmental connection, which has not been sufficiently provided in sustainability reporting to date. 35J.-P. Gauzès, “Potential need for changes to the Governance and Funding of EFRAG,” EFRAG, Brussels, 2021. The ESRS take up existing frameworks such as GRI, SASB and TCFD and are based on the principle of dual materiality. 36EFRAG, “[Draft] European Sustainability Reporting Guidelines 1,” 2022. There are two perspectives in the materiality assessment: 1. necessary information about the company’s impact on sustainability issues should be disclosed (inside out) and 2. necessary information about how sustainability issues will affect the company’s future development, performance and position (outside in). A sustainability issue is considered material if it is material from an impact perspective (non-financial) or from a financial perspective (financial) – or both. Thus, dual materiality means that information is material even if only one of the two perspectives is fulfilled. 37EFRAG, “[Draft] European Sustainability Reporting Guidelines 1,” 2022.

On 29 April 2022 EFRAG published the first official drafts (see figure), on which a consultation was held until 08 August 2022. In August, the 750 responses received will be analyzed and presented to the EFRAG Sustainability Reporting Board and the EFRAG Sustainability Reporting TEG in September. 38Akzente, “Der neue Standard,” [Online]. Available: https://www.csr-berichtspflicht.de/esrs. [Accessed 07 09 2022]. The finished drafts are to be handed over to the European Commission on November 15. 39EFRAG, “Due process procedures for sustainability reporting standard-setting,” [Online]. Available: https://www.efrag.org/Activities/2106151549247651/Due-Process-Procedures-for-Sustainability-Reporting-Standard-Setting-. [Accessed 07 09 2022].

The greatest difficulty for companies at present is to keep track of current legislative developments at the dynamic legislative developments at the EU level and to adjust their reporting to the new standards. 40PWC, “Sustainability Reporting News- Aktuelles zur Nachhaltigkeitsberichterstattung- das Wesentliche,,” 01.01.2022.

3 Key performance indicators and effects on sustainability

The previous section highlighted important tools for implementing sustainability reporting in companies. Besides the growing global sustainable investment market and legal framework, the SDGs are pushing companies to implement sustainability reporting in their business models. Stakeholders are no longer interested only in a company’s financial performance; there is an increasing interest in ESG information, which pressures firms to improve their ESG performance.42 Dienes, D., Sassen, R. & Fischer, J. (2016). What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. SAMPJ, 7 (2), 154–189. 43 Barker, R., Eccles, R. G. & Serafeim, G. (2020). The Future of ESG Is … Accounting? Harvard Business Review This determines the scope of the ESG performance measurement system and the transparency that can be achieved through sustainability reporting. The need to make corporate sustainability performance clear, comparable, and verifiable is getting more and more important.

3.1 Key performance indicators in sustainability reports

Measuring relevant ecological facts and sustainability is a key task in sustainability accounting, sustainability reporting, and sustainability management. It can be challenging for a company when it comes to the point of measuring and reporting sustainability performance, because, for example, environmental and social issues are measured by different measures than financial issues, such as air pollution in tons of CO₂ or water consumption in liters. Also, sustainability performance cannot be measured directly, individual indicators do not share a unit of measurement, and the information used to measure a firm’s sustainability is provided by the company itself; also, it is not always audited.44 Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge. Measured sustainability performance must be considered as a construct, a theoretical structure that cannot be observed but is expressed in numbers using indicators. Sustainability reports rely on sustainability indicators; they become an effective tool for communicating and measuring a company’s sustainability performance.45 Tarquinio, L., Raucci, D. & Benedetti, R. (2018). An Investigation of Global Reporting Initiative Performance Indicators in Corporate Sustainability Reports: Greek, Italian and Spanish Evidence. Sustainability, 10 (4), 897 Standardized guidelines for sustainability reporting, such as the GRI, SASB, AA, and ISO 26000, provide indicators, called KPIs, that are key elements that help companies and stakeholders have an overview of a company’s sustainability performance.46 Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge.

Usually, sustainability reports consist of three different categories: economic, social, and environmental. Each category reports in different measures and narratives to communicate the social and environmental footprint to the stakeholders. All three categories have their own indicators, such as supplier relations and average income in the economic category, work security measures and health and safety records in the social category, and energy and water usage or carbon dioxide emissions in the environmental category.47 Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge. According to Compare Your Footprint, some of the most important KPIs for sustainability reports are, inter alia, carbon footprint, water usage, energy consumption, supply chain miles, and waste recycling rate.

A growing number of companies adopt one or several of the mentioned or other standardized guidelines with provided KPIs in their sustainability reports. According to Rimmel, companies that decide to publish a sustainability report are confronted with several difficulties. The relevant indicators must be defined, the collection of information must be systemized and adjusted, and the individual indicators do not share a unit of measurement.48 Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge. Regarding the selection of KPIs, Lydenberg, Rogers and Wood recommend implementing indicators that are specific to the industry sector and using only a small number of indicators.49 Lydenberg, S., Rogers, J. & Wood, D. From transparency to performance. Industry-Based Sustainability Reporting on Key Issues). Cambridge, US: Initiative for responsible investment

3.1.1 The Global Reporting Initiative and key performance indicators

The GRI, the standard that has become the most widely used guideline for sustainability reporting, identifies a list of sustainability indicators across economic (GRI 201–GRI 207), environmental (GRI 301–GRI 308), and social (GRI 401–GRI 419) aspects.50 Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge. Based on its own provisions, its indicators have been developed through GRI’s multistakeholder processes to address aspects that a company and its stakeholders have identified as relevant.51 Lydenberg, S., Rogers, J. & Wood, D. From transparency to performance. Industry-Based Sustainability Reporting on Key Issues). Cambridge, US: Initiative for responsible investment No other reporting standard is used by more companies than the GRI; the United Nations Global Compact recommends the publication of a sustainability report according to GRI standards.52 (2018). CSR und Compliance. Synergien nutzen durch ein integriertes Management). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg Its standards together give the standard disclosures and useful tools to simplify the work of structuring the content of a sustainability report, which helps in selecting the most suitable indicators for measuring sustainability performance.53 Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge. As previously explained, GRI performance indicators are divided into three different categories: economic, environmental, and social (see GRI).

As mentioned before, standards and frameworks can also be used together in a sustainability report. GRI and the SASB have identified that several companies use both standards to generate information that meets the needs of all businesses and markets. They decided to publish A Practical Guide to Sustainability Reporting Using GRI and SASB Standards to provide a helpful guideline with examples to companies that have chosen to use the two sets of standards to communicate their sustainability performance effectively.54 Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (2021). How to use the GRI standards. Retrieved on 03.08.21: https://www.globalreporting.org/how-to-use-the-gri-standards

3.1.2 Sustainable Development Goals linked to key performance indicators

The United Nations General Assembly in 2015 established a set of 17 SDGs, which “provide a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future.”55 United Nations (2021). The 17 goals. Retrieved on 31/08/21: https://sdgs.un.org/goals Since 2016, companies have started to integrate SDGs linked to KPIs into their reports. The United Nations Global Compact, GRI, and partners developed a guide on how companies can integrate the SDGs linked to KPIs through a three-step approach and in alignment with recognized principles and reporting standards. In September 2020, they published a paper to show stakeholders and other companies how to implement KPIs linked with SDGs in their sustainability reports. One example is a Spanish company called Iberdrola, which is based in the energy sector. It identified Goal 7 on Affordable and Clean Energy and Goal 13 on Climate Action as priorities for the company, because those are the two goals it believes it can have the most impact on.56 United Nations Global Compact & Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (2018). Integrating the Sustainable Development Goals into Corporate Reporting: A Practical Guide. Retrieved on 31/08/21: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/library/5628

3.2 Effects on sustainability

The measurement of sustainability indicators leads to a control instrument for the sustainability activities of a company, and the sustainable management plan can base its decisions and strategies on these results. With that base of information, companies can work on their sustainability performance and their impact on environmental and social issues. According to sustainability reports, it can be assumed that KPIs have an impact on sustainability. As Figure 3 from Iberdrola shows, there was an increase in the total energy consumption within the organization, but it had a decrease in its coal consumption. It could be assumed that Iberdrola is handling coal sustainably.57 Iberdrola (2020). Sustainability report 2019. Retrieved on 31/08/21: https://www.iberdrola.com/shareholders-investors/annual-reports/2019#1 Figure 4 shows another example, from AAK. In its sustainability report, it presents that its water consumption per unit of processed material decreased in 2019 by 2.3% compared to 2018.58 AAK (2020). Sustainability report 2019. Retrieved on 31/08/21: https://ebooks.exakta.se/aak/2020/sustainability_report_2019/page_1.html However, it should be pointed out that, at this point, further long-term studies, which are researching the effects of individual KPIs in relation to sustainability, are missing, which would be needed to make this a reliable statement

Gramlich of Washington State University published a paper in 2017 that examines whether mandatory CSR reporting affects corporate environmental degradation (or pollution) levels in China. His research shows that mandatory CSR disclosure can have an positive effect on the environment, for example, in terms of lowering the pollution level. The paper supports the view that firms will cut down on their pollution if issuing a CSR report becomes mandatory. Nevertheless, Gramlich also concludes that further research is necessary. Other signals or regulations besides the CSR reporting could had been the reason for the firm-level pollution reduction.59 Gramlich, J. & Huang, L. (2017). The Effect of Mandated CSR Disclosure on the Pollution Levels of Publicly-Traded Chinese Firms. SSRN Journal

Calabrese analyzed the possible presence of greenwashing practices related to sustainability reports. In his study, he used the sustainability reports of 50 Italian companies, and his results show how companies implement a higher number of environmental indicators to pursue a greenwashing strategy with the objective of obfuscating their limited commitment to sustainability and managing stakeholders’ perceptions of their benefits.60 Calabrese, A., Costa, R., Levialdi Ghiron, N. & Menichini, T. (2019). Materiality analysis in sustainability reporting: A tool for directing corporate sustainability towards emerging economic, environmental and social opportunities, 25 (5), 1016–1038.

4 Drivers and barriers

When driving forward change and innovation in accounting and reporting, there are factors that favor the implementation of new techniques, guidelines, and ways of thinking and factors that represent obstacles. There are internal and external drivers that encourage and support companies to introduce sustainability into their existing accounting and reporting structures but also internal and external barriers that make it harder and less desirable for companies to concern themselves with sustainability accounting and reporting. This chapter describes different drivers and barriers while also presenting some ideas on how to overcome these barriers.

4.1 Drivers

4.1.1 External drivers

Considering the various factors that can change the process of accounting and reporting in companies, some of the main forces behind the inclusion of sustainability and non-materiality in reports are often external. Rules, frameworks, and standards as well as laws can be reliable ways to initiate change.61 Cho, C. H. et al. (2020). Advancing Sustainability Reporting in Canada: 2019 Report on Progress. Accounting Perspectives, 19 (3), 181–204. Government legislation and multinational agreements also play a big role in driving sustainability developments and sparking interest in them through participation in global initiatives such as the Kyoto Protocol (1998), the Copenhagen Accord (2009), and Agenda 2030 (2015). Several countries have introduced their own national initiatives as well, such as Canada’s Federal Sustainable Development Strategy (2016–2019), which resulted in driving forward the use of sustainability reporting (more on legal regulations).

Many of the frameworks for sustainability accounting and reporting that have followed these initiatives have arisen from the demand of stakeholders and investors for reports that include financial, social, and environmental information.62 KPMG (2017). The road ahead. The KPMG survey of corporate responsibility reporting 2017. As there is a growing interest in sustainability issues by the public, consumers’ needs for information about the sustainability of a business have also greatly increased.63 Arroyo, P. (2012). Management accounting change and sustainability: an institutional approach. (Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change), 8 (3), 286–309. To satisfy these needs, businesses are required to rethink their accounting and reporting processes. Therefore, two of the central drivers of sustainability accounting and reporting were the publication of the GRI and the integrated reporting framework of the IIRC, which led to a new era of corporate reporting by including nonfinancial information in the finalized report. This increased stakeholder engagement and stakeholder understanding of a firm’s performance.64 Baboukardos, D., Mangena, M. & Ishola, A. (2021). Integrated thinking and sustainability reporting assurance: International evidence. (Business Strategy and the Environment), 30 (4), 1580–1597. Guidelines, structures, and frameworks are external drivers of the implementation and management of sustainability accounting and reporting.

The CSR Directive Implementation Act, which was developed by Germany to implement EU Directive 2014/95/EU (also called the Nonfinancial Reporting Directive), can be viewed as an important example of an external, political driver of sustainability accounting and reporting. This directive makes publishing a comprehensive nonfinancial report mandatory, starting in fiscal year 2017, for large German capital market–oriented companies, credit institutions, and insurance companies. Information about environmental, social, and employee-related matters, respect for human rights, and anti-corruption measures is required to be reported. While some of the 536 affected companies had already published a nonfinancial report in the past, many others were driven to submit a nonfinancial report for the first time in their business history.65 Hoffmann, E., Dietsche, C. & Hobelsberger, C. (2018). Between mandatory and voluntary: non-financial reporting by German companies. NachhaltigkeitsManagementForum, 26 (1-4), 47–63.

4.1.2 Internal drivers

One of the main internal drivers of sustainability reporting is firm size. Studies indicate a positive relationship between firm size and CSR disclosure. One possible explanation for this relationship is that larger firms tend to have stronger motives to issue voluntary reports. As market-oriented companies have a high media exposure and have their reputation, brand, and corporate identity in mind, a sustainability report serves as a tool to present the company as sustainable. Larger companies also have more information-seeking stakeholders to satisfy, especially in the public sector, as larger companies often have more impact on CSR-related topics worldwide. Another relationship to be examined is the decrease in the cost of preparing a sustainability report as firm size increases. Smaller companies may not have the resources and/or experience to create a nonfinancial report on their own while larger companies already have experts and structures that allow them to do so.66 Dienes, D., Sassen, R. & Fischer, J. (2016). What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. SAMPJ, 7 (2), 154–189.

Another internal driver of sustainability reporting and accounting is the level of corporate governance and the existence of sustainability/audit committees, since both are positively correlated to CSR disclosure. This relationship can be explained by the idea that the sustainable alignment is executed best if appropriate corporate governance systems and sustainability management are implemented in the company. By incorporating sustainability initiatives into the existing corporate governance framework and reporting, a competitive benefit can be achieved. Therefore, sustainability reporting is easier to execute when a company already has structures into which it can be implemented.67 Dienes, D., Sassen, R. & Fischer, J. (2016). What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. SAMPJ, 7 (2), 154–189.

4.2 Barriers

4.2.1 External barriers

One of the biggest hindrances to sustainability reports is their voluntary nature. Although there are many guidelines, frameworks, and regulations, nonfinancial reporting remains voluntary for most companies worldwide. This not only causes distracting variations across reports, as companies themselves decide what information to include and how to display it,68 Cho, C. H., Guidry, R. P., Hageman, A. M. & Patten, D. M. (2012). Do actions speak louder than words? An empirical investigation of corporate environmental reputation. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 37 (1), 14–25. 69 Ioannou, I. & Serafeim, G. (2017). The Consequences of Mandatory Corporate Sustainability Reporting. SSRN Journal, 7387. but also creates a barrier to companies that want to start sustainability reporting, as the differences between the many reports and frameworks can be confusing (see Possibilities for implementation).

Having to decide between many different frameworks and guidelines creates another barrier for companies that have no experience of working with any of them yet. Differences in quality also mean differences in comprehensiveness, which makes it even harder for other companies to get an idea of what a “good” sustainability report looks like.70 Cho, C. H. et al. (2020). Advancing Sustainability Reporting in Canada: 2019 Report on Progress. Accounting Perspectives, 19 (3), 181–204.

The missing regulations regarding the types of information portrayed in sustainability reports create another barrier. As social and environmental information is often not reliable, homogenous, or entirely measurable,71 Arroyo, P. (2012). Management accounting change and sustainability: an institutional approach. (Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change), 8 (3), 286–309. companies choose methodologies and standards that best suit their business goals when including nonfinancial information in their reports. This causes variation in quality between reports and makes it harder for unexperienced companies to manage information, gain experience, and complete their database, making the accounting process more complicated and leading to a lower quality of report.72 Cho, C. H. et al. (2020). Advancing Sustainability Reporting in Canada: 2019 Report on Progress. Accounting Perspectives, 19 (3), 181–204.

Even though frameworks and standards exist, many of them differ in their definition of the materiality concept. For instance, the German CSR Directive Implementation Act defines material aspects as those that have a direct impact on business operation while the GRI also includes direct social and ecological impacts, but only if they are relevant for the business in the mid- or long term. This fundamental difference in definition could lead to a lack of transparency, creating another barrier for companies that want to start incorporating sustainability reporting and accounting.73 Arroyo, P. (2012). Management accounting change and sustainability: an institutional approach. (Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change), 8 (3), 286–309.

4.2.2 Internal barriers

One of the bigger internal barriers is the complicated preparation process companies are required to follow to provide a high-quality nonfinancial report. Researchers have discovered that, in order to create reports that disclose valuable information, companies need to set up necessary structures, management systems, programs, and a corresponding database. As these nonfinancial structures can differ greatly from the usual financial structures, regular sustainability reporting requires large amounts of time and money to prepare and initiate.74 Arroyo, P. (2012). Management accounting change and sustainability: an institutional approach. (Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change), 8 (3), 286–309.

As small- and medium-sized companies are not as exposed to the public as large companies, size can be a barrier as well. The public is not as interested in small- and medium-sized companies as it is in large ones. They have much less influence on social and ecological factors in each region and therefore face a lesser need to provide information about their impact. From a cost/benefit perspective, it may not be very economical for small- and medium-sized companies to create a sustainability report, as they can rarely use the report for marketing or brand purposes.75 Dienes, D., Sassen, R. & Fischer, J. (2016). What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. SAMPJ, 7 (2), 154–189.

4.2.3 Overcoming barriers

To overcome the barriers that stem from variations between guidelines and from the voluntary nature of sustainability reporting and accounting, regulations by governments, such as the CSR Directive Implementation Act in Germany, may be needed at the international level. Developing and implementing these standards on a transnational level and creating transnational regulations, such as the directive on nonfinancial reporting in 2014 by the European Union, would help in overcoming the problem of every individual company figuring out an optimal framework and would decrease variations between the reports of companies that are already experienced in sustainability accounting and reporting.76 Smeuninx, N., Clerck, B. de & Aerts, W. (2020). Measuring the Readability of Sustainability Reports: A Corpus-Based Analysis Through Standard Formulae and NLP. International Journal of Business Communication, 57 (1), 52–85.

The great variation in quality, manner, and rate of reporting, which represents a barrier for companies that want to or must start using sustainability accounting and reporting techniques, can be overcome by sticking to established guidelines, such as the GRI. Whether they have a reporting obligation under law or are doing it voluntarily, applying established guidelines allows companies to lay the foundation for future improvement of their sustainability reporting and accounting processes and for more comparability between companies. Using guidelines that have proven to be successful in presenting nonfinancial information makes it easier for unexperienced companies to get started with sustainability reporting and accounting. Overcoming this additional barrier of incomprehensiveness could make the inclusion of sustainability in reporting and accounting more approachable even for small- and medium-sized companies.77 Arroyo, P. (2012). Management accounting change and sustainability: an institutional approach. (Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change), 8 (3), 286–309.

The obstacles created by the expensive setting up of systems and the complex acquisition of knowhow could be overcome by promoting assurance for sustainability reports by accounting firms. By reviewing a sustainability report, experts provide their expertise to unexperienced companies, impart their knowhow regarding sustainability reporting and accounting processes, and can drive uniformity forward by eliminating inconsistencies in multiple reports. As shown in studies, assurance in sustainability reporting has a positive effect on the transparency of reports78 Darnall, N., Seol, I. & Sarkis, J. (2009). Perceived stakeholder influences and organizations’ use of environmental audits. Accounting, Organizations and Society (34), 170–187. 79 Perego, P. & Kolk, A. (2012). Multinationals’ accountability on sustainability. The evolution of third-party assurance of sustainability reports. Journal of Business Ethics (110), 173–190. 80 Pflugrath, G., Roebuck, P. & Simnett, R. (2011). Impact of assurance and assurer’s professional affiliation on financial analysts’ assessment of credibility of corporate social responsibility information. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory., 30 (3), 239–254. 81 Simnett, R., Vanstraelen, A. & Chua, W. F. (2009). Assurance on sustainability reports. An internatonal comparison. The Accounting Review, 84 (3), 937–967. and on investor’s perceptions of the importance of sustainability reporting.82 Cheng, M. M., Green, W. J. & Ko, J. C. W. (2015). The impact of strategic relevance and assurance of sustainability indicators on investors’ decisions. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 34 (1), 131–161. This could also increase the incentive for small- and medium-sized companies to submit sustainability reports, as the public may have a better perception and interest in an assured sustainability report than in a self-declared sustainability report.83 O’Dywer B., Owen, D. & Unterman, J. (2011). Seeking legitimacy for assurance forms. The case of assurance on sustainability reporting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 1 (36), 31–52.

5 Criticism

Sustainability accounting has been the subject of criticism in recent years. While there are several ways to make the implementation of standardized guidelines easier (see Overcoming barriers), systemic issues must be addressed. Sustainability reporting has a very diverse audience; not only investors but also interested citizens read them. However, companies devote little attention to their reports’ readability. Sustainability reports tend to be especially difficult to understand, even more difficult than financial reports. As the target audience is very heterogeneous and does not have the same abilities as sophisticated investors, people have to rely on experts’ opinions.84 Smeuninx, N., Clerck, B. de & Aerts, W. (2020). Measuring the Readability of Sustainability Reports: A Corpus-Based Analysis Through Standard Formulae and NLP. International Journal of Business Communication, 57 (1), 52–85.

In addition, there is a risk that companies may engage in so-called cheap talk. Cheap talk refers to information that is costless, usually neither compulsory for the company nor provable, but has a huge effect on the reader’s opinions.85 Farrell, J. & Rabin, M. (1996). Cheap Talk. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10 (3), 103–118.. CSR disclosures are, therefore, accused of being just cheap talk meant to fulfil stakeholders’ desires.86 Gramlich, J. & Huang, L. (2017). The Effect of Mandated CSR Disclosure on the Pollution Levels of Publicly-Traded Chinese Firms. SSRN Journal. In fact, Cossin et al. found that cheap talk reduces CSR.87 Cossin, D., Smulowitz, S. & Lu, A. (2021). The High Cost of Cheap Talk: How Disingenuous Ethical Language Can Reflect Agency Costs. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2021 (1), 10437. It has also been proven that several companies engage in cheap talk in self-reported anti-corruption efforts.88 Healy, P. M. & Serafeim, G. (2016). An Analysis of Firms’ Self-Reported Anticorruption Efforts. The Accounting Review, 91 (2), 489–511. Nevertheless, Bae et al. suggest that investors are, in fact, able to differentiate between CSR and cheap talk.89 Kee-Hong Bae, Sadok El Ghoul, Zhaoran (Jason) Gong & Omrane Guedhami (2021). Does CSR matter in times of crisis? Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Corporate Finance, 67, 101876. In summary, the literature shows inconclusive results.

Furthermore, sustainability reporting may lead to “greenwashing.” Greenwashing refers to corporate practices of trying to showcase or communicate as sustainable operating procedures that are not sustainable. Therefore, companies might use their sustainability report as a marketing tool to communicate their ESG efforts even though they are not fully met.90 Dienes, D., Sassen, R. & Fischer, J. (2016). What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. SAMPJ, 7 (2), 154–189. Greenwashing is often not seen as fraudulent behavior, although it meets the same technical tests used to determine fraudulent reporting.91 Kurpierz, J. R. & Smith, K. (2020). The greenwashing triangle: adapting tools from fraud to improve CSR reporting. SAMPJ, 11 (6), 1075–1093. However, regulating greenwashing may not be the answer, since it does not increase positive environmental externalities. Allowing greenwashing may even increase the number of environmentally friendly products in the market.92 Lee, H. C. B., Cruz, J. M. & Shankar, R. (2018). Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Issues in Supply Chain Competition: Should Greenwashing Be Regulated? Decision Sciences, 49 (6), 1088–1115. Additionally, Ruiz-Blanco found in his empirical analysis that companies that follow GRI guidelines and are in environmentally sensitive industries tend to greenwash less.93 Ruiz-Blanco, S., Romero, S. & Fernandez-Feijoo, B. (2021). Green, blue or black, but washing–What company characteristics determine greenwashing? Environ Dev Sustain. Consequently, greenwashing may not be as detrimental as previously thought. However, further research is necessary.

Putting the sole focus on easily measurable but isolated KPIs is not always sufficient for achieving sustainability. These numbers are rather reducing than inducing. Conformity and standardization are not effective in addressing sustainable development. One way to solve this problem is to introduce innovative accounting methods. However, a problem with the term innovation is that there are several definitions that vary depending on the discipline.94 Schaltegger, S., Etxeberria, I. Á. & Ortas, E. (2017). Innovating Corporate Accounting and Reporting for Sustainability – Attributes and Challenges. Sust. Dev., 25 (2), 113–122. The effectiveness of sustainability reporting is also questioned by some researchers. Cahyandito found that sustainability reporting does not function well as a communication tool, because stakeholders do not extensively read the reports, even if the reporting quality is high. As a way to solve this problem, sustainability reports should make the intention and objectives clear so that stakeholders do not view them as pure advertisements.95 Fani Cahyandito (2005). The Effectiveness of Sustainability Reporting: Is it Only About the Report’s Design and Contents? Retrieved on 31/08/21: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1670702

References

- 1Nikolina Markota Vukić, R. Vukovic & Donato Calace (2018). Non-financial reporting as a new trend in sustainability accounting. The Journal of Accounting and Management), 13–26.

- 2Dienes, D., Sassen, R. & Fischer, J. (2016). What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. SAMPJ, 7 (2), 154–189.

- 3Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge.

- 4Mathews, M. R. (1995). Social and Environmental Accounting: A Practical Demonstration of Ethical Concern? Journal of Business Ethics, 14 (8), 663.

- 5Gray, R. (2001). Thirty years of social accounting, reporting and auditing: what (if anything) have we learnt? Bus Ethics Eur Rev, 10 (1), 9–15.

- 6Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge.

- 7Man, M. & Bogeanu-Popa, M.-M. (2020). Impact of Non-Financial Information on Sustainable Reporting of Organisations’ Performance: Case Study on the Companies Listed on the Bucharest Stock Exchange. Sustainability, 12 (6), 2179.

- 8Dienes, D., Sassen, R. & Fischer, J. (2016). What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. SAMPJ, 7 (2), 154–189.

- 9Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). About us. Retrieved on 09/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/about/.

- 10Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (2021). Our mission and history. Retrieved on 31/07/21: https://www.globalreporting.org/about-gri/mission-history/.

- 11Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). About us. Retrieved on 09/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/about/.

- 12Kaur, A. & Lodhia, S. (2018). Stakeholder engagement in sustainability accounting and reporting. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 31 (1), 338–368.

- 13Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (2021). Our mission and history. Retrieved on 31/07/21: https://www.globalreporting.org/about-gri/mission-history.

- 14Daizy, Mitali Sen & N. Das (2013). Corporate Sustainability Reporting: A Review of Initiatives and Trends. The IUP Journal of Accounting Research and Audit Practices), 7–18.

- 15Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (2021). Download the standards. Retrieved on 03/08/21: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/download-the-standards.

- 16Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (2021). Services. Retrieved on 04/08/21: https://www.globalreporting.org/reporting-support/services.

- 17Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). About us. Retrieved on 09/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/about.

- 18Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). Materiality Map. Retrieved on 11/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/standards/materiality-map.

- 19Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). Find your industry. Retrieved on 13/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/find-your-industry.

- 20Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). Implementation Primer. Retrieved on 13/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/implementation-primer.

- 21Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). Structured Reporting Using XBRL. Retrieved on 20/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/structured-reporting-xbrl.

- 22Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). Companies Reporting with SASB Standards. Retrieved on 20/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/company-use/sasb-reporters

- 23Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). Alliance Membership. Retrieved on 20/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/alliance-membership

- 24Cortese, Rubino in Cinquini, De Luca, Non-financial Disclosure and Integrated Reporting.

- 25Transition to integrated reporting, IR Framework, September 2021.

- 26Transition to integrated reporting, IR Framework, September 2021.

- 27Cortese, Rubino in Cinquini, De Luca, Non-financial Disclosure and Integrated Reporting.

- 28AccountAbility (AA) (2021). About us. Retrieved on 21/08/21: https://www.accountability.org/about

- 29AccountAbility (AA) (2021). Standards. Retrieved on 21/08/21: https://www.accountability.org/standards

- 30AccountAbility (AA) (2021). Standards. Retrieved on 21/08/21: https://www.accountability.org/standards

- 31AccountAbility (AA) (2021). Advisory. Retrieved on 21/08/21: https://www.accountability.org/advisory

- 32International Organization for Standardization (ISO) (2021). About us. Retrieved on 22/08/21: https://www.iso.org/about-us.html

- 33International Organization for Standardization (ISO) (2021). ISO 26000. Retrieved on 22/08/21: https://www.iso.org/iso-26000-social-responsibility.html

- 34EFRAG, “Due process procedures for sustainability reporting standard-setting,” [Online]. Available: https://www.efrag.org/Activities/2106151549247651/Due-Process-Procedures-for-Sustainability-Reporting-Standard-Setting-. [Accessed 07 09 2022].

- 35J.-P. Gauzès, “Potential need for changes to the Governance and Funding of EFRAG,” EFRAG, Brussels, 2021.

- 36EFRAG, “[Draft] European Sustainability Reporting Guidelines 1,” 2022.

- 37EFRAG, “[Draft] European Sustainability Reporting Guidelines 1,” 2022.

- 38Akzente, “Der neue Standard,” [Online]. Available: https://www.csr-berichtspflicht.de/esrs. [Accessed 07 09 2022].

- 39EFRAG, “Due process procedures for sustainability reporting standard-setting,” [Online]. Available: https://www.efrag.org/Activities/2106151549247651/Due-Process-Procedures-for-Sustainability-Reporting-Standard-Setting-. [Accessed 07 09 2022].

- 40PWC, “Sustainability Reporting News- Aktuelles zur Nachhaltigkeitsberichterstattung- das Wesentliche,,” 01.01.2022.

- 41EFRAG, “Public consultation on the first set of Draft ESRS,” [Online]. Available: https://efrag.org/lab3. [Accessed 07 09 2022].

- 42Dienes, D., Sassen, R. & Fischer, J. (2016). What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. SAMPJ, 7 (2), 154–189.

- 43Barker, R., Eccles, R. G. & Serafeim, G. (2020). The Future of ESG Is … Accounting? Harvard Business Review

- 44Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge.

- 45Tarquinio, L., Raucci, D. & Benedetti, R. (2018). An Investigation of Global Reporting Initiative Performance Indicators in Corporate Sustainability Reports: Greek, Italian and Spanish Evidence. Sustainability, 10 (4), 897

- 46Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge.

- 47Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge.

- 48Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge.

- 49Lydenberg, S., Rogers, J. & Wood, D. From transparency to performance. Industry-Based Sustainability Reporting on Key Issues). Cambridge, US: Initiative for responsible investment

- 50Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge.

- 51Lydenberg, S., Rogers, J. & Wood, D. From transparency to performance. Industry-Based Sustainability Reporting on Key Issues). Cambridge, US: Initiative for responsible investment

- 52(2018). CSR und Compliance. Synergien nutzen durch ein integriertes Management). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg

- 53Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge.

- 54Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (2021). How to use the GRI standards. Retrieved on 03.08.21: https://www.globalreporting.org/how-to-use-the-gri-standards

- 55United Nations (2021). The 17 goals. Retrieved on 31/08/21: https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- 56United Nations Global Compact & Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (2018). Integrating the Sustainable Development Goals into Corporate Reporting: A Practical Guide. Retrieved on 31/08/21: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/library/5628

- 57Iberdrola (2020). Sustainability report 2019. Retrieved on 31/08/21: https://www.iberdrola.com/shareholders-investors/annual-reports/2019#1

- 58AAK (2020). Sustainability report 2019. Retrieved on 31/08/21: https://ebooks.exakta.se/aak/2020/sustainability_report_2019/page_1.html

- 59Gramlich, J. & Huang, L. (2017). The Effect of Mandated CSR Disclosure on the Pollution Levels of Publicly-Traded Chinese Firms. SSRN Journal

- 60Calabrese, A., Costa, R., Levialdi Ghiron, N. & Menichini, T. (2019). Materiality analysis in sustainability reporting: A tool for directing corporate sustainability towards emerging economic, environmental and social opportunities, 25 (5), 1016–1038.

- 61Cho, C. H. et al. (2020). Advancing Sustainability Reporting in Canada: 2019 Report on Progress. Accounting Perspectives, 19 (3), 181–204.

- 62KPMG (2017). The road ahead. The KPMG survey of corporate responsibility reporting 2017.

- 63Arroyo, P. (2012). Management accounting change and sustainability: an institutional approach. (Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change), 8 (3), 286–309.

- 64Baboukardos, D., Mangena, M. & Ishola, A. (2021). Integrated thinking and sustainability reporting assurance: International evidence. (Business Strategy and the Environment), 30 (4), 1580–1597.

- 65Hoffmann, E., Dietsche, C. & Hobelsberger, C. (2018). Between mandatory and voluntary: non-financial reporting by German companies. NachhaltigkeitsManagementForum, 26 (1-4), 47–63.

- 66Dienes, D., Sassen, R. & Fischer, J. (2016). What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. SAMPJ, 7 (2), 154–189.

- 67Dienes, D., Sassen, R. & Fischer, J. (2016). What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. SAMPJ, 7 (2), 154–189.

- 68Cho, C. H., Guidry, R. P., Hageman, A. M. & Patten, D. M. (2012). Do actions speak louder than words? An empirical investigation of corporate environmental reputation. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 37 (1), 14–25.

- 69Ioannou, I. & Serafeim, G. (2017). The Consequences of Mandatory Corporate Sustainability Reporting. SSRN Journal, 7387.

- 70Cho, C. H. et al. (2020). Advancing Sustainability Reporting in Canada: 2019 Report on Progress. Accounting Perspectives, 19 (3), 181–204.

- 71Arroyo, P. (2012). Management accounting change and sustainability: an institutional approach. (Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change), 8 (3), 286–309.

- 72Cho, C. H. et al. (2020). Advancing Sustainability Reporting in Canada: 2019 Report on Progress. Accounting Perspectives, 19 (3), 181–204.

- 73Arroyo, P. (2012). Management accounting change and sustainability: an institutional approach. (Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change), 8 (3), 286–309.

- 74Arroyo, P. (2012). Management accounting change and sustainability: an institutional approach. (Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change), 8 (3), 286–309.

- 75Dienes, D., Sassen, R. & Fischer, J. (2016). What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. SAMPJ, 7 (2), 154–189.

- 76Smeuninx, N., Clerck, B. de & Aerts, W. (2020). Measuring the Readability of Sustainability Reports: A Corpus-Based Analysis Through Standard Formulae and NLP. International Journal of Business Communication, 57 (1), 52–85.

- 77Arroyo, P. (2012). Management accounting change and sustainability: an institutional approach. (Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change), 8 (3), 286–309.

- 78Darnall, N., Seol, I. & Sarkis, J. (2009). Perceived stakeholder influences and organizations’ use of environmental audits. Accounting, Organizations and Society (34), 170–187.

- 79Perego, P. & Kolk, A. (2012). Multinationals’ accountability on sustainability. The evolution of third-party assurance of sustainability reports. Journal of Business Ethics (110), 173–190.

- 80Pflugrath, G., Roebuck, P. & Simnett, R. (2011). Impact of assurance and assurer’s professional affiliation on financial analysts’ assessment of credibility of corporate social responsibility information. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory., 30 (3), 239–254.

- 81Simnett, R., Vanstraelen, A. & Chua, W. F. (2009). Assurance on sustainability reports. An internatonal comparison. The Accounting Review, 84 (3), 937–967.

- 82Cheng, M. M., Green, W. J. & Ko, J. C. W. (2015). The impact of strategic relevance and assurance of sustainability indicators on investors’ decisions. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 34 (1), 131–161.

- 83O’Dywer B., Owen, D. & Unterman, J. (2011). Seeking legitimacy for assurance forms. The case of assurance on sustainability reporting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 1 (36), 31–52.

- 84Smeuninx, N., Clerck, B. de & Aerts, W. (2020). Measuring the Readability of Sustainability Reports: A Corpus-Based Analysis Through Standard Formulae and NLP. International Journal of Business Communication, 57 (1), 52–85.

- 85Farrell, J. & Rabin, M. (1996). Cheap Talk. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10 (3), 103–118..

- 86Gramlich, J. & Huang, L. (2017). The Effect of Mandated CSR Disclosure on the Pollution Levels of Publicly-Traded Chinese Firms. SSRN Journal.

- 87Cossin, D., Smulowitz, S. & Lu, A. (2021). The High Cost of Cheap Talk: How Disingenuous Ethical Language Can Reflect Agency Costs. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2021 (1), 10437.

- 88Healy, P. M. & Serafeim, G. (2016). An Analysis of Firms’ Self-Reported Anticorruption Efforts. The Accounting Review, 91 (2), 489–511.

- 89Kee-Hong Bae, Sadok El Ghoul, Zhaoran (Jason) Gong & Omrane Guedhami (2021). Does CSR matter in times of crisis? Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Corporate Finance, 67, 101876.

- 90Dienes, D., Sassen, R. & Fischer, J. (2016). What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. SAMPJ, 7 (2), 154–189.

- 91Kurpierz, J. R. & Smith, K. (2020). The greenwashing triangle: adapting tools from fraud to improve CSR reporting. SAMPJ, 11 (6), 1075–1093.

- 92Lee, H. C. B., Cruz, J. M. & Shankar, R. (2018). Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Issues in Supply Chain Competition: Should Greenwashing Be Regulated? Decision Sciences, 49 (6), 1088–1115.

- 93Ruiz-Blanco, S., Romero, S. & Fernandez-Feijoo, B. (2021). Green, blue or black, but washing–What company characteristics determine greenwashing? Environ Dev Sustain.

- 94Schaltegger, S., Etxeberria, I. Á. & Ortas, E. (2017). Innovating Corporate Accounting and Reporting for Sustainability – Attributes and Challenges. Sust. Dev., 25 (2), 113–122.

- 95Fani Cahyandito (2005). The Effectiveness of Sustainability Reporting: Is it Only About the Report’s Design and Contents? Retrieved on 31/08/21: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1670702

- 1Nikolina Markota Vukić, R. Vukovic & Donato Calace (2018). Non-financial reporting as a new trend in sustainability accounting. The Journal of Accounting and Management), 13–26.

- 2Dienes, D., Sassen, R. & Fischer, J. (2016). What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. SAMPJ, 7 (2), 154–189.

- 3Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge.

- 4Mathews, M. R. (1995). Social and Environmental Accounting: A Practical Demonstration of Ethical Concern? Journal of Business Ethics, 14 (8), 663.

- 5Gray, R. (2001). Thirty years of social accounting, reporting and auditing: what (if anything) have we learnt? Bus Ethics Eur Rev, 10 (1), 9–15.

- 6Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge.

- 7Man, M. & Bogeanu-Popa, M.-M. (2020). Impact of Non-Financial Information on Sustainable Reporting of Organisations’ Performance: Case Study on the Companies Listed on the Bucharest Stock Exchange. Sustainability, 12 (6), 2179.

- 8Dienes, D., Sassen, R. & Fischer, J. (2016). What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. SAMPJ, 7 (2), 154–189.

- 9Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). About us. Retrieved on 09/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/about/.

- 10Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (2021). Our mission and history. Retrieved on 31/07/21: https://www.globalreporting.org/about-gri/mission-history/.

- 11Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). About us. Retrieved on 09/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/about/.

- 12Kaur, A. & Lodhia, S. (2018). Stakeholder engagement in sustainability accounting and reporting. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 31 (1), 338–368.

- 13Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (2021). Our mission and history. Retrieved on 31/07/21: https://www.globalreporting.org/about-gri/mission-history.

- 14Daizy, Mitali Sen & N. Das (2013). Corporate Sustainability Reporting: A Review of Initiatives and Trends. The IUP Journal of Accounting Research and Audit Practices), 7–18.

- 15Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (2021). Download the standards. Retrieved on 03/08/21: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/download-the-standards.

- 16Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (2021). Services. Retrieved on 04/08/21: https://www.globalreporting.org/reporting-support/services.

- 17Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). About us. Retrieved on 09/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/about.

- 18Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). Materiality Map. Retrieved on 11/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/standards/materiality-map.

- 19Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). Find your industry. Retrieved on 13/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/find-your-industry.

- 20Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). Implementation Primer. Retrieved on 13/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/implementation-primer.

- 21Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). Structured Reporting Using XBRL. Retrieved on 20/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/structured-reporting-xbrl.

- 22Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). Companies Reporting with SASB Standards. Retrieved on 20/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/company-use/sasb-reporters

- 23Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2021). Alliance Membership. Retrieved on 20/08/21: https://www.sasb.org/alliance-membership

- 24Cortese, Rubino in Cinquini, De Luca, Non-financial Disclosure and Integrated Reporting.

- 25Transition to integrated reporting, IR Framework, September 2021.

- 26Transition to integrated reporting, IR Framework, September 2021.

- 27Cortese, Rubino in Cinquini, De Luca, Non-financial Disclosure and Integrated Reporting.

- 28AccountAbility (AA) (2021). About us. Retrieved on 21/08/21: https://www.accountability.org/about

- 29AccountAbility (AA) (2021). Standards. Retrieved on 21/08/21: https://www.accountability.org/standards

- 30AccountAbility (AA) (2021). Standards. Retrieved on 21/08/21: https://www.accountability.org/standards

- 31AccountAbility (AA) (2021). Advisory. Retrieved on 21/08/21: https://www.accountability.org/advisory

- 32International Organization for Standardization (ISO) (2021). About us. Retrieved on 22/08/21: https://www.iso.org/about-us.html

- 33International Organization for Standardization (ISO) (2021). ISO 26000. Retrieved on 22/08/21: https://www.iso.org/iso-26000-social-responsibility.html

- 34EFRAG, “Due process procedures for sustainability reporting standard-setting,” [Online]. Available: https://www.efrag.org/Activities/2106151549247651/Due-Process-Procedures-for-Sustainability-Reporting-Standard-Setting-. [Accessed 07 09 2022].

- 35J.-P. Gauzès, “Potential need for changes to the Governance and Funding of EFRAG,” EFRAG, Brussels, 2021.

- 36EFRAG, “[Draft] European Sustainability Reporting Guidelines 1,” 2022.

- 37EFRAG, “[Draft] European Sustainability Reporting Guidelines 1,” 2022.

- 38Akzente, “Der neue Standard,” [Online]. Available: https://www.csr-berichtspflicht.de/esrs. [Accessed 07 09 2022].

- 39EFRAG, “Due process procedures for sustainability reporting standard-setting,” [Online]. Available: https://www.efrag.org/Activities/2106151549247651/Due-Process-Procedures-for-Sustainability-Reporting-Standard-Setting-. [Accessed 07 09 2022].

- 40PWC, “Sustainability Reporting News- Aktuelles zur Nachhaltigkeitsberichterstattung- das Wesentliche,,” 01.01.2022.

- 41EFRAG, “Public consultation on the first set of Draft ESRS,” [Online]. Available: https://efrag.org/lab3. [Accessed 07 09 2022].

- 42Dienes, D., Sassen, R. & Fischer, J. (2016). What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. SAMPJ, 7 (2), 154–189.

- 43Barker, R., Eccles, R. G. & Serafeim, G. (2020). The Future of ESG Is … Accounting? Harvard Business Review

- 44Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge.

- 45Tarquinio, L., Raucci, D. & Benedetti, R. (2018). An Investigation of Global Reporting Initiative Performance Indicators in Corporate Sustainability Reports: Greek, Italian and Spanish Evidence. Sustainability, 10 (4), 897

- 46Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge.

- 47Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge.

- 48Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge.

- 49Lydenberg, S., Rogers, J. & Wood, D. From transparency to performance. Industry-Based Sustainability Reporting on Key Issues). Cambridge, US: Initiative for responsible investment

- 50Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge.

- 51Lydenberg, S., Rogers, J. & Wood, D. From transparency to performance. Industry-Based Sustainability Reporting on Key Issues). Cambridge, US: Initiative for responsible investment

- 52(2018). CSR und Compliance. Synergien nutzen durch ein integriertes Management). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg

- 53Rimmel, G. (2021). Accounting for sustainability). London: Routledge; Earthscan from Routledge.

- 54Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (2021). How to use the GRI standards. Retrieved on 03.08.21: https://www.globalreporting.org/how-to-use-the-gri-standards

- 55United Nations (2021). The 17 goals. Retrieved on 31/08/21: https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- 56United Nations Global Compact & Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (2018). Integrating the Sustainable Development Goals into Corporate Reporting: A Practical Guide. Retrieved on 31/08/21: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/library/5628

- 57Iberdrola (2020). Sustainability report 2019. Retrieved on 31/08/21: https://www.iberdrola.com/shareholders-investors/annual-reports/2019#1

- 58AAK (2020). Sustainability report 2019. Retrieved on 31/08/21: https://ebooks.exakta.se/aak/2020/sustainability_report_2019/page_1.html

- 59Gramlich, J. & Huang, L. (2017). The Effect of Mandated CSR Disclosure on the Pollution Levels of Publicly-Traded Chinese Firms. SSRN Journal

- 60Calabrese, A., Costa, R., Levialdi Ghiron, N. & Menichini, T. (2019). Materiality analysis in sustainability reporting: A tool for directing corporate sustainability towards emerging economic, environmental and social opportunities, 25 (5), 1016–1038.

- 61Cho, C. H. et al. (2020). Advancing Sustainability Reporting in Canada: 2019 Report on Progress. Accounting Perspectives, 19 (3), 181–204.

- 62KPMG (2017). The road ahead. The KPMG survey of corporate responsibility reporting 2017.

- 63Arroyo, P. (2012). Management accounting change and sustainability: an institutional approach. (Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change), 8 (3), 286–309.

- 64Baboukardos, D., Mangena, M. & Ishola, A. (2021). Integrated thinking and sustainability reporting assurance: International evidence. (Business Strategy and the Environment), 30 (4), 1580–1597.

- 65Hoffmann, E., Dietsche, C. & Hobelsberger, C. (2018). Between mandatory and voluntary: non-financial reporting by German companies. NachhaltigkeitsManagementForum, 26 (1-4), 47–63.

- 66Dienes, D., Sassen, R. & Fischer, J. (2016). What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. SAMPJ, 7 (2), 154–189.

- 67Dienes, D., Sassen, R. & Fischer, J. (2016). What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. SAMPJ, 7 (2), 154–189.