Author: Michael Sieveke, January 13, 2024

1 Definition and Relevance

Sustainability is a topic of ever-increasing importance, especially with regard to climate change. In the period from 1880 to 2023, the Earth’s surface temperature rose by more than 1.3 degrees Celsius due to human influence, including the emission of carbon dioxide. Changes in the global climate system have increased dramatically since 1950.1Additionally, the forecasts of various greenhouse gas scenarios have indicated that the average increase in warming by the end of the 21st century will be 1.5 to 5.7 degrees Celsius compared to the reference period of 1850–1900. Strong climate protection measures are needed to counteract this development.1

According to studies conducted by McKinsey in 2021, the topic of sustainability is also becoming increasingly important to consumers. Seventy-eight percent of those surveyed said they pay attention to products that are sustainable and fairly produced.2 The most important factors for consumers are that the products are free from environmentally harmful ingredients (70% of respondents) and that as little carbon dioxide as possible is emitted during production and transportation (67% of respondents). Consumers said they are also prepared to pay higher prices for sustainable products.2

In a world increasingly characterized by environmental and climate issues, sustainable business models are becoming ever more important for companies. These businesses are faced not only with the challenge of ensuring successful economic operations but also must take responsibility for the long-term impact of their actions on society and the environment.

Sustainable business models offer companies the opportunity to solve ecological and social problems through their value creation activities and, at the same time, increase the company’s economic performance.3 To achieve this, firms must change their perspective and go beyond the boundaries and definitions of traditional business models.4

This thesis, therefore, uses a literature review to examine sustainable business models, their forms, and how a company can implement these business models. It also takes a closer look at sustainable business model innovations and presents some tools to support companies in the development of business models. Finally, this thesis lists the drivers of and barriers to sustainable business models.

2 Business Model

A business model is a conceptual instrument that describes how a company functions. It can be used to analyze the company, compare it with others, manage it, and drive its innovation.5 In addition to the organization itself, a business model includes various stakeholders, such as customers, suppliers, and partners, whose relationships and interactions are integral to the company’s value creation process.6

A variety of approaches can be taken regarding the relationship between a business model and corporate strategy. Some authors consider the business model to be a tool, designed to implement the given corporate strategy and align this strategy with the company’s outlined objectives. 7,8 Others state that the corporate strategy implements the given business model.9 Either way, it can be inferred that the corporate strategy has a close relationship with the business model.

The literature often describes various components of a business model framework, so that there is no universally accepted definition. Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010) stated that a “business model best be described through nine basic building blocks that show the logic of how a company intends to make money” (p.15).10These building blocks are customer segments, value propositions, channels, customer relationships, revenue streams, key resources, key activities, key partnerships, and cost structure.10

This thesis uses the categorization of Richardson (2008), which divides the business model into three key components: value proposition, value creation and delivery, and value capture.11 The value proposition refers to the benefits a company offers its customers, typically through products or services that meet specific customer needs. Value creationincludes the processes involved in delivering these offerings, which may involve developing new business opportunities or entering new markets. Finally, value capture refers to the mechanisms through which the company generates revenue from the value created, including cost structures and income streams.

3 Sustainable Business Model

Traditional business models tend to focus on maintaining existing or gaining short-term competitive advantages, while ignoring social and environmental issues. This is often due to pressure from investors and other interest groups.12Sustainable business models can help solve environmental and social problems through a company’s value creation activities while boosting its economic performance.3 To achieve this, companies need to change their perspective and go beyond the boundaries and definitions of traditional business models.4

According to Bocken et al. (2014), it is clear that profits and competitive advantages have been achieved through greater efficiency and improvements in quality; however, “It is not always so clear how delivering social and environmental value might translate into profit and competitive advantage for the firm” (p.44).13 In theory, if a company has established a perfectly sustainable business model, it should create a value for the environment and a social value while still generating profit from the products and services it provides.4

The definitions in the literature share the view that sustainable business models are an adaptation of the traditional business model concept, incorporating additional characteristics and objectives. Either new concepts and principles are integrated in which sustainability plays a central role or the components of the business model framework are expanded to include the aspect of sustainability. This means that sustainability is integrated into the value proposition, value creation and delivery, and value capture.14

Sustainable business models, therefore, follow the triple bottom line, which means generating value on social, economic, and environmental levels.13 Not only is the firm-level perspective taken into account but also the systems perspective; in other words, a larger stakeholder group is considered, and society and the environment are recognized as important stakeholders. Attempts are made to balance the interests of each group.15

Schaltegger et al. (2016) defined a sustainable business model as follows: “A business model for sustainability helps [in] describing, analyzing, managing, and communicating a company’s sustainable value proposition to its customers and all other stakeholders, how it creates and delivers this value, and how it captures economic value while maintaining or regenerating natural, social, and economic capital beyond its organisational boundaries” (p.6).16

To summarize, a sustainable business model differs from a traditional business model and value creation strategy. First, it is based on the idea of sustainable development. Then, it encompasses a comprehensive concept of value that takes into account both environmental and social aspects. It also focuses on the interests of all relevant stakeholders and not just customers, investors, or business partners. Finally, it pursues a systemic approach that considers the various interactions with the natural and social environments.17

4 Sustainable Business Model Innovation

To integrate a sustainable business model into a company with an existing business model or to create a completely new business model, innovations are required that create new value for the company and its stakeholders. These changes can be achieved by altering the building blocks of the business model.18 These can be incremental or radical changes, with radical changes having the greatest potential to generate value for the company and society.19

According to Bocken et al. (2014), “Business model innovations for sustainability are defined as: Innovations that create significant positive and/or significantly reduced negative impacts for the environment and/or society, through changes in the way the organisation and its value-network create, deliver value, and capture value (i.e. create economic value) or change their value propositions” (p.44).13

As depicted in the figure based on the model presented by Geissdorfer et al. (2018), a distinction is made among four types of sustainable business model innovation.14 The first is sustainable start-ups, which describe new companies that are founded on the basis of a sustainable business model. The second type is sustainable business model transformation. Here, the current business model of an existing company is adapted to create a sustainable business model. The third type of sustainable business innovation type is sustainable business model diversification, in which a sustainable business model is established alongside existing business models without any major changes. The last type is sustainable business model acquisition.14 In this case, an additional “sustainable business model is identified, acquired, and integrated into the organization” (p. 408).14

In their analysis, Boons et al. (2013) concluded that business model innovations can be divided into three categories—organizational, technological, and social innovations—which can be combined with each other or, in some cases, must be integrated. For example, a technological innovation also requires an organizational innovation. 20 A technological innovation can improve the production process, optimize the end product, and enhance the use of the product by the consumer, thereby influencing various stakeholders. According to Boons et al. (2013), business models are market devices that can overcome the barriers outside and inside the company that accompany the introduction of new clean technology. In this context, they can be seen as “mediators between technologies of production and consumption” (p.14).20 The following three combinations are possible:20

- A new business model can leverage existing technologies;

- Existing business models can be enhanced by new technologies; or

- New technologies can either create new business models or transform existing ones, and the other way around.

Organizational innovations are about adopting alternative paradigms to the classic economic perspective and, thus, resulting in an organizational or cultural change. While technological innovations see business models as market devices that are intended to promote innovation, sustainable business models in this context are seen as “expressions of organizational and cultural changes in business practices and attitudes that integrate needs and aspirations of sustainable development” (p.15).20

Social innovations are often linked to technological or organizational innovations, since they are “providing solutions to problems of others, i.e. of societal groups that lack the resources or capabilities to help themselves” (p.15).20 This can include product or process innovations with a social objective or entrepreneurial actions that lead to the development of social enterprises. In this context as well, business models should serve as market devices that help in “creating and further developing markets for innovations with social purpose” (p.15).20

5 Guiding Principles

To help managers and entrepreneurs who want to transform their company’s current business model into a sustainable business model or to develop a completely new sustainable business model, Breuer et al. (2018) have drawn up the following four guiding principles that can be used as a basis for development without prescribing a specific outcome:17

- Sustainable orientation,

- Extended value creation,

- Systems thinking, and

- Stakeholder integration.

The first principle is sustainable orientation, which is a central point in the development of a sustainable business model. Sustainability should be considered on three levels to ensure its effective implementation into the business model: a general level, a level of action-oriented principles, and a level of practical concepts.17

At the general level, the basic idea of sustainability is described. The definitions are so numerous that they are not explored in this paper. At the level of action-oriented principles, Breuer et al. (2018) refer to principles such as “eco-efficiency, consistency, self-sufficiency, fair distribution of wealth, and the avoidance of unacceptable risks”(p.271) through which sustainability can be implemented in the company.17 The level of practical concepts includes ideas such as zero-emission production processes or cradle-to-cradle designs. With the former, these processes capture and dispose of carbon dioxide and other pollutants, releasing only water vapor and nitrogen into the atmosphere. With the latter, materials and components can be repurposed or recycled, thereby reducing their environmental impact or adding to their sustainable value.17

The principle of extended value creation aims to ensure that the development of the sustainable business model not only generates value for individual companies and their customers but also creates value for “market and non-market actors in monetary and non-monetary terms” (p.271).17 Even values and normative orientations that are typically overlooked should be considered because of their impact on value creation. These values are expressed in normative statements, business model components, and, especially, in the value proposition. Normative statements include the corporate vision and purpose.21 According to Breuer et al., the value proposition design must be considered for sustainable value creation, and the single-bottom-line approach for the entire business model must be extended to a triple-bottom-line approach.17 This can cause problems, especially when it comes to setting priorities. Clear guidelines, therefore, should be negotiated by the parties involved to guide decision-making and to identify the problems to be solved. The desired values should be defined in these guidelines, which are particularly helpful in cases where it is not possible to agree on clearly defined goals, measurable performance indicators, or key financial figures.17

The third principle is systems thinking. When creating a business model, it is important for entrepreneurs and managers to have an overview of the entire system described by a business model and to understand that a business model is a boundary-spanning activity system in which various activities are interdependent.17 Due to the increasing specialization and division of labor in the economy, social interaction is an important factor in innovation processes, allowing for employee acquisition and integration of external resources and knowledge. Systemic approaches to innovation, therefore, are required.22 To implement the principles of sustainable orientation and extended value creation, the management of a company must consider the entire system. An example of this is life cycle thinking, which is used in many concepts, including the circular economy. There, the entire life cycle of the product must be considered, which automatically requires systems thinking.17

The last principle, stakeholder integration, is an essential component in the design of sustainable business models. However, this is not a simple process, and Breuer et al. (2018) highlight a number of reasons why this is not straightforward.17 For example, stakeholders can be used to procure resources such as capital, which requires a complex exchange between both parties, as the different interests of the parties must be considered. However, it is not always clear what the interests of the individual stakeholders are, especially in cases where medium- and long-term impacts are difficult to predict. Breuer et al. (2018) cite climate change as an example.17 Another challenge to stakeholder integration is the possible conflicts between the company’s sustainability goals and the interests of its stakeholders or between the interests of individual stakeholders.17

6 Archetypes

It has been established previously that sustainable business models are a further development of traditional business models and are generally created through an innovation process. To gain a better overview of the various possibilities for sustainable business models and the areas in which such innovations can be advanced, this chapter presents the archetypes of sustainable business models introduced by Bocken et al. (2014).13

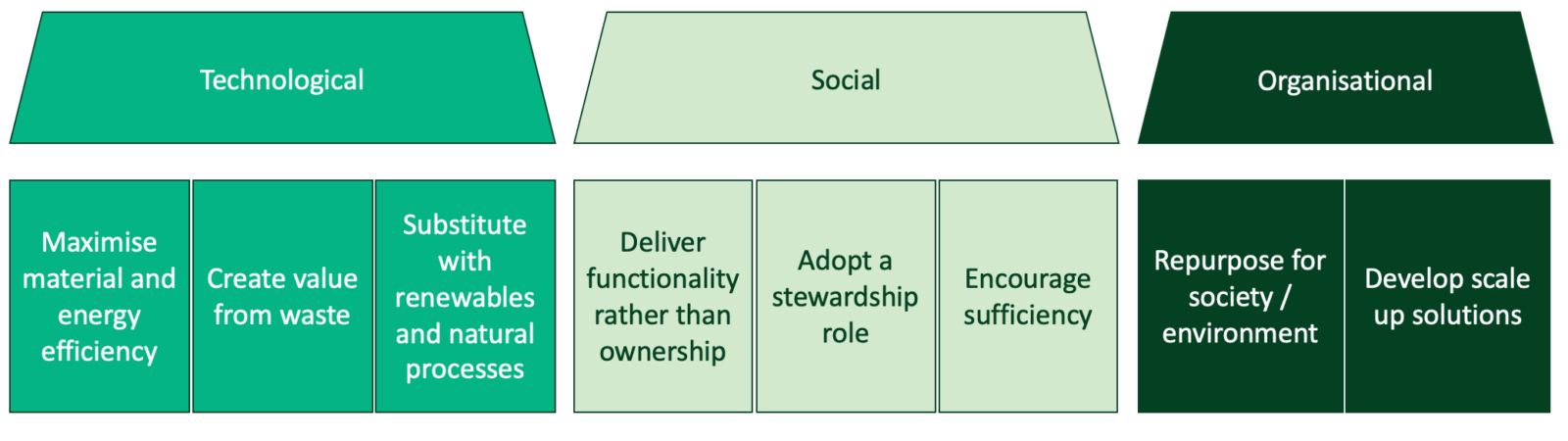

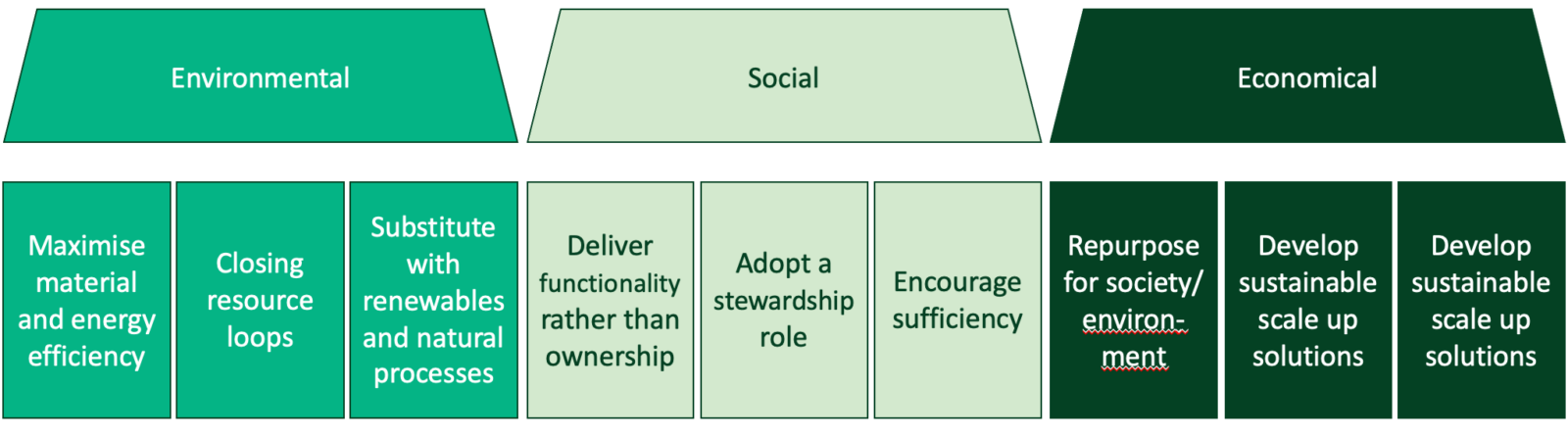

These eight archetypes are divided into three categories, which are based on the types of business model innovation according to Boons et al. (2013): technological, social, and organizational innovations.13 This presentation was then adapted over time, as “the relationships between business models and sustainability innovations depend on the focus of a company’s activities” (p.46).23 In sustainable business models, as explained previously, these are based on the triple bottom line—the ecological, social, and economic challenges—in which the company attempts to generate business opportunities through innovation. A further modification was made by Ritala (2018) to produce nine archetypes of sustainable business models.23,24

6.1 Environmental

The first archetype is to maximize material and energy efficiency. The value proposition in this archetype, according to Bocken et al. (2014), is that a product or service is created that has the same functions as a comparable product or service but that consumes fewer resources, produces less waste, and creates less pollution.13 The focus here is on product and process innovations, but supply chains can also be optimized to reduce environmental impacts.13

Additionally, companies can save costs by improving efficiency in the production process and thereby reducing resource consumption and environmental impact. However, possible negative effects of optimizing the production process can be the loss of jobs. Furthermore, rebound effects can occur if only one company chooses this archetype.24

The following examples are provided for this archetype in the literature:13,24

- Low carbon/manufacturing solutions,

- Lean manufacturing,

- Additive manufacturing, and

- Dematerialization of products and packaging.

The next archetype presented by Bocken et al. (2014) is creating value from waste or, in the more recent presentation,closing resource loops.13,23 In this example, the products and materials that would be sorted out as waste are reused in production.25 In the best case, a product is always completely reused and, thus, circulates throughout the production process.23 To achieve this goal, Bocken et al. (2014) state that new partnerships can be formed with other companies, “potentially across industries, to capture and transfer waste streams” (p.49).13 The advantages of this archetype are that waste is reduced and that a value is generated from that waste, which can also bring new income streams for the company. One danger is that shortened sales cycles may cause higher material consumption, thereby creating more waste.24

For this archetype, Bocken et al. 2014 mentioned the following examples:13

- Circular economy, closed loop;

- Cradle to cradle;

- Reuse, recycle, remanufacture; and

- Industrial symbiosis.

The final environmental archetype for sustainable business models is substitute with renewables and natural processes. Here, companies should reduce their dependence on finite resources in current production systems and thereby trim their environmental impact. Renewable resources and natural processes should come to the forefront, also promoting business independence.13 The advantages are that the use of finite resources is reduced alongside the curtailment of waste and environmental pollution. This archetype, therefore, also contributes to the green economy. However, the side effects of replacing finite materials must be considered on a case-by-case basis. For example, it must be taken into account that, when using solar energy, materials for the production of solar energy are not easily recyclable.24

Examples of this archetype include the following:23

- Move from non-renewable to renewable energy sources,

- Solar and wind power-based energy innovations,

- Zero emissions initiative, and

- Blue economy.

6.2 Social

In the group of social innovations, the first type is deliver functionality rather than ownership. As its name suggests, the company’s value proposition is not about selling a product to the consumer but about satisfying their needs through services, so they do not have to own the product themselves. Especially in the case of products that are rarely used, this model offers significant added value for the user.13 Even very expensive products can become affordable for consumers who do not have to buy the entire product but can borrow it for a certain period of time.25 To implement this archetype, companies need to overhaul their range of products and services.13 Instead of encouraging customers to buy new products often, companies seek to maximize the lifetime of their products so they are as economical as possible.13

The advantages of this archetype are that the behavior of users and manufacturers can be influenced positively, and the need for physical goods can be reduced.23 Resource consumption can also be lowered.13 However, positive impacts can be achieved only if, in addition to the introduction of this approach, there is also an increase in efficiency in the company.24

Bocken et al. (2014) provide the following examples:13

- Product-oriented product, service, or system, such as maintenance, extended warranty;

- Use-oriented product, service, or system, such as rental, lease, shared;

- Result-oriented product, service, or system, such as pay per use; and

- Private finance initiative.

According to Bocken et al. (2014), the next archetype in the social sphere is adopt a stewardship role.13 They define this archetype as follows: “Proactively engaging with all stakeholders to ensure their long-term health and well-being” (p.51).13 The stakeholders here also include society and the environment as companies begin taking additional responsibility for environmental and social problems.

Companies seeking to adopt a stewardship role ensure that their own operations and production systems meet this responsibility and work to ensure that their partners and suppliers also contribute to this goal. To implement this archetype, it may be necessary to restructure the corporate network.13 Through this archetype, the company has the opportunity to increase the value of its own brand and, as a result, can demand higher prices for its products. Furthermore, the model can have a positive effect on the employees if the working environment is improved, which benefits the company.13 As with the previous archetype, this example must also be combined with an improvement in efficiency, as the improvement in the environmental area could fail to materialize otherwise.24

Examples of this archetype in the literature are the following:23

- Biodiversity protection,

- Consumer care promoting consumer health and well-being,

- Ethical trade (fair trade), and

- Radical transparency about environmental and societal impacts.

The last archetype from the social area of innovation in the illustration by Bocken et al. (2014) is encouraging sufficiency.13 This models promote sustainability by reducing material throughput and energy consumption, encouraging end users to make do with less.26 The value proposition is to create products and services that reduce consumer consumption, which can be realized, for example, through products with a longer lifespan. Achieving such a goal also would reduce the company’s production. At the same time, consumers’ consumption behavior should be influenced to ensure that they use products longer and live more sustainably.13 To do this, the company must align its activities, including marketing tasks, and its corporate environment toward the principle that less is consumed and wasted when producing items with a longer lifespan.13 Through this business model, a loyal customer base can be developed, composed of shoppers who have the same values and are willing to buy the products at premium prices. One disadvantage of this model is that it challenges the basic economic principles for growth.23

Bocken et al. (2014) provide the following examples:13

- Consumer education, communication;

- Demand management;

- Slow fashion;

- Product longevity; and

- Premium branding and limited availability.

6.3 Economical

The first archetype at the economic level is re-purpose the business for society and the environment. In a brief definition, Bocken et al. (2014) describe this archetype as “prioritizing delivery of social and environmental benefits rather than economic profit (i.e., shareholder value) maximization, through close integration between the firm and local communities and other stakeholder groups. The traditional business model where the customer is the primary beneficiary may shift” (p.53).13 In this model, companies aim to achieve positive value for all stakeholders. Particular emphasis is placed on society and the environment.23 This system-level approach can provide resilience by supporting stakeholders in any economic situation.13

The company’s activities can include, for example, reforestation or the development of a community by providing food and education.24 Such activities are often undertaken by non-profit organizations as well as for-profit companies seeking to fulfill their social and environmental goals. Another approach is a combination of these two business models, in which two business units cooperate with each other. One of the units would be profit-oriented, with some of the profits generated being invested in the non-profit business unit to pursue social and economic goals.13 One problem with this archetype may be that it can continue to serve niche needs only without changes in the political or economic systems.24

Examples of this archetype are the following:13

- Not-for-profit businesses;

- Hybrid businesses or social enterprises that seek to make a profit;

- Businesses with alternative ownership, such as cooperative, mutual, collectives; and

- Social and biodiversity regeneration initiatives.

The eighth archetype is inclusive value creation. This model is about “sharing resources knowledge, ownership, and wealth creation” (p.219), where new business opportunities can be created and wealth distributed.24,25 It is also about addressing customer groups that do not correspond to the mainstream groups, but this can have the disadvantage that more products are purchased and more services used due to the larger customer segment being targeted.23 Therefore, it is important here, as with many of the other archetypes, that the possible innovations within the archetype are also accompanied by efficiency increases.23

Examples are the following:23

- Collaborative approaches (sourcing, production, lobbying);

- Peer-to-peer sharing;

- Inclusive innovation; and

- Base-of-pyramid solutions.

The ninth and final archetype is developing sustainable scale-up solutions. For this type, the value proposition of the business model is to scale “sustainability solutions to maximize benefits for society and the environment” (p.54).13 To achieve scale, new partnerships and business relationships must be formed and the business model implemented through the appropriate channels.13 It is important that both sides benefit from partnership and scale through variable or fixed fees or other benefits such as market penetration.13

The advantages of this are manifold. On the one hand, a start-up can develop into a large-scale project, while on the other hand, this archetype can also lead to sustainability spreading throughout a sector or industry. Additionally, collaboration and the search for scaling solutions can lead to new innovations.23 However, there is a risk that in the search for scaling opportunities, sustainability goals may take a back seat, and radical innovations may not be thoroughly tested.23

Examples in the literature are the following:13

- Incubators and entrepreneur-support models,

- Open innovation,

- Patient or slow capital,

- Impact investing or capital,

- Crowdfunding or sourcing, and

- Peer-to-peer lending.

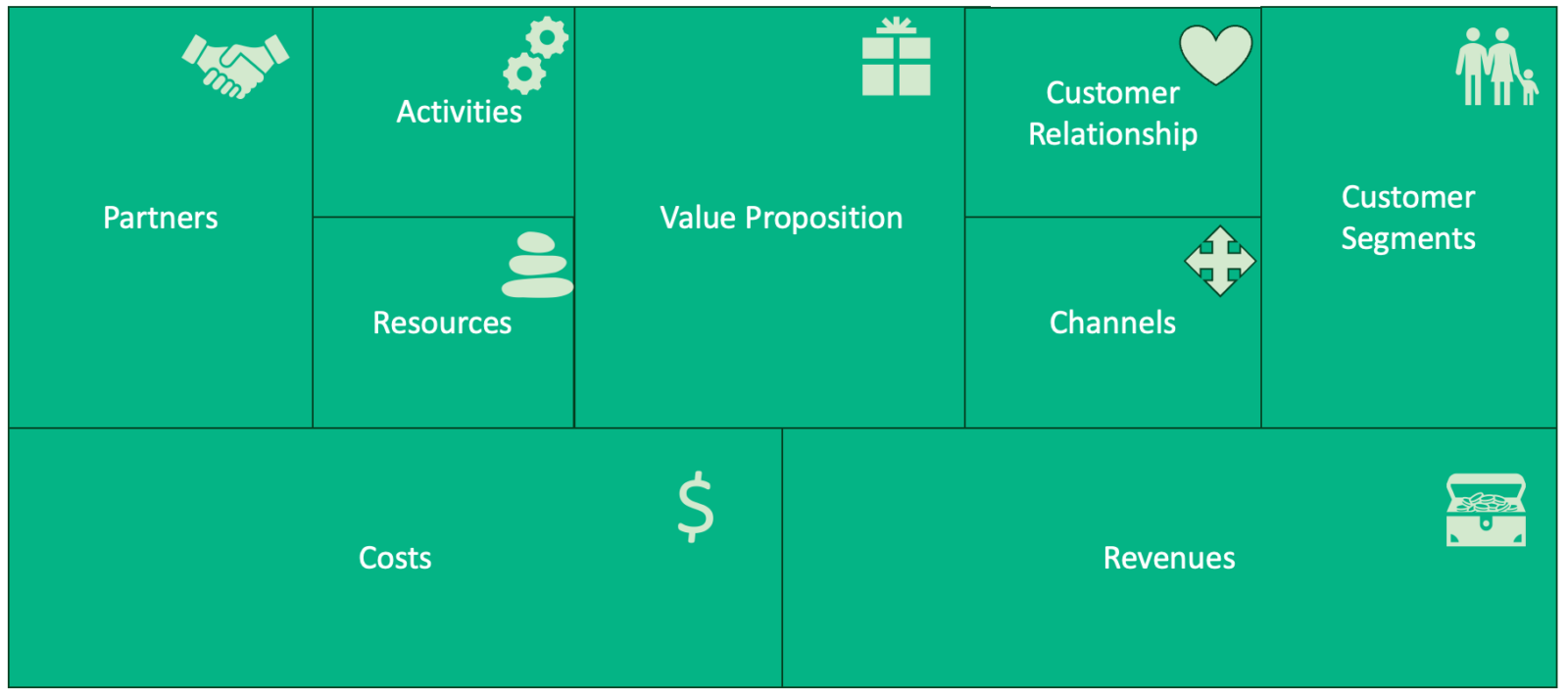

7 Business Model Canvas

The Business Model Canvas is a representation of a business model created by Osterwalder, which serves to visualize and structure the business model, but can also be used to develop new business models or to further develop existing business models.27 Many other tools have been developed based on the Business Model Canvas, and these are discussed in the following sections. For this reason, the Business Model Canvas is explained in the following.

According to Osterwalder’s presentation, a business model consists of nine building blocks, which form the basis of the model: customer segments, value propositions, channels, customer relationships, revenue streams, key resources, key activities, key partnerships, and cost structure.10

The first building block of a business model is customer segments. Osterwalder describes customers as the “heart of any business model”(p.20).10 Customers can be divided into different segments according to various factors, such as needs, interests, behaviors, or income strength. Based on the segment’s classification, the company can then decide which customer segments it wishes to serve and build the business model according to that decision.10

The second building block is value propositions. This building block concerns the products and services that a company offers to satisfy the needs of its customers. The products and services therefore generally relate to the previously defined customer segments.10

The third building block is the channels. This component describes how the company approaches the customer segments and transfers the value proposition. This module therefore includes the communication, distribution, and sales channels. 10

The fourth building block is customer relationships. Customer relationships influence the overall customer experience and therefore are of some importance. A company should therefore consider what kind of relationship it seeks to build with the different customer segments it wishes to serve. According to Osterwalder (2010), “Customer relationships may be driven by the following motivations: Customer acquisition, customer retention, boosting sales (upselling)” (p.28).10

The fifth building block is represented by revenue streams. The company needs to determine the value at which the customer of a particular customer segment is willing to purchase the product or service, hence, the pricing mechanisms of the revenue streams can differ. Revenue streams can be divided into two types. On the one hand, there are transaction revenues in which the customer pays once for the service offered. On the other hand, there are recurring revenues, which are ongoing payments from the customer.10

The sixth segment of the Business Model Canvas lists the key resources of a company that are necessary to implement the business model and deliver value to the customer. These can be “physical, financial, intellectual, or human”(p.34) resources, according to Osterwalder (2010).10 Examples include machinery, buildings, patents, capital, or skilled workers.

The seventh building block is key activities. Key activities are activities that a company needs to perform to allow the business model to be implemented. For example, these may represent activities in production, research and development, marketing, or relationship management.10

Key partnerships are the eighth building block of a business model. This building block concerns the suppliers and partners with whom the business model is being implemented. The partnerships can be differentiated into strategic alliances, cooperation, joint ventures, and buyer-supplier relationships.10

The final building block is the cost structure, which are the key costs incurred by the chosen business model. This building block builds on the building blocks of key resources, key activities, and key partnerships, as “[c]reacting and delivering value, maintaining customer relationships, and generating revenue all incur costs” (p.40).10

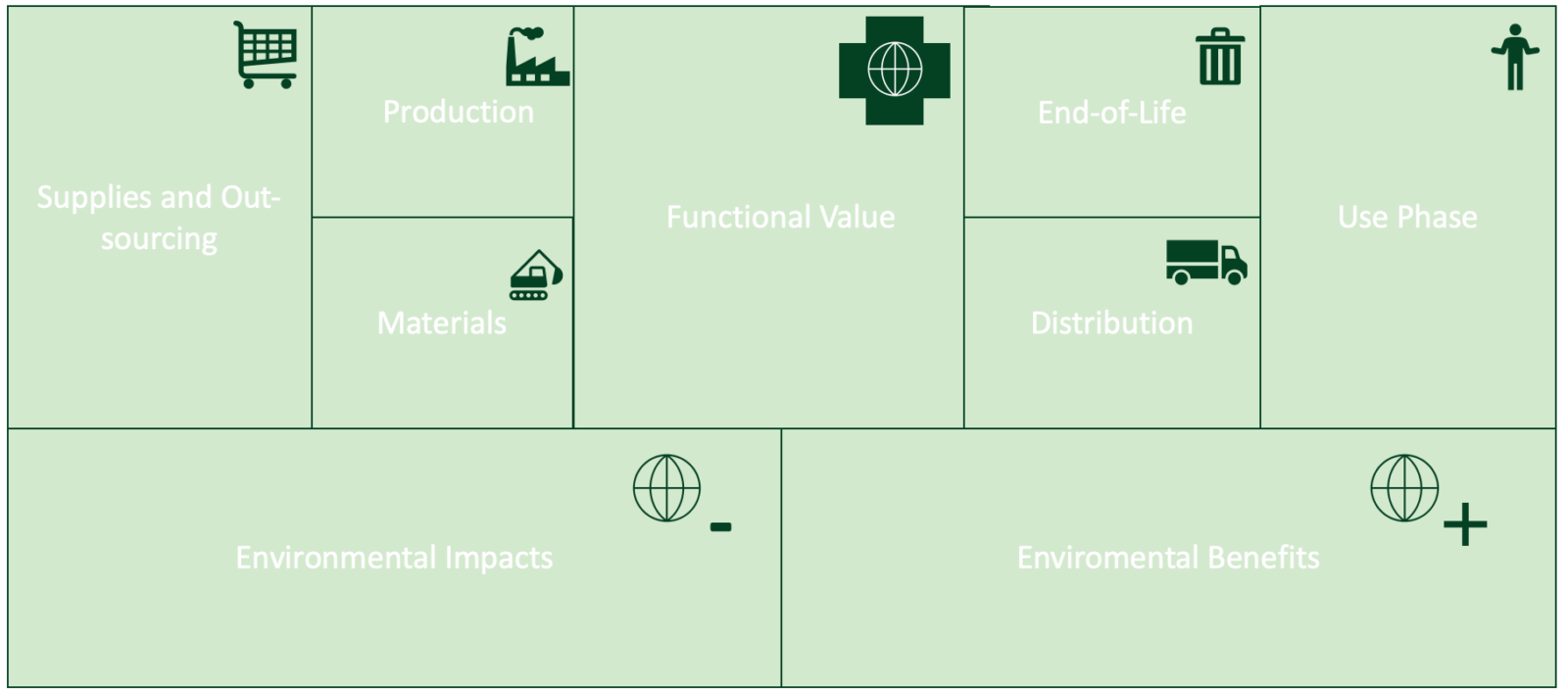

8 Triple Layered Business Model Canvas

The Triple Layered Business Model Canvas is a tool that can be used to develop sustainable business models and therefore also supports sustainable business model innovation. It is an extension of the previously presented Business Model Canvas, with two additional layers.27 In addition to the already familiar economic layer, the model also includes environmental and social layers, hence, this tool takes the triple bottom line into account. It therefore aims to generate value on all three levels.23 These layers are explained in the following subsections.

8.1 Environmental Layer

The environmental layer of the Triple Layered Business Model Canvas was originally created using the life cycle thinking approach, which allows the environmental impact of products, services, and processes to be measured using indicators such as CO2 emissions. It aims to determine “how the organization generates more environmental benefits than environmental impacts” (p.1477).27 By incorporating this layer into the business model, it can be determined which areas of the business model have an impact on the environment and are therefore suitable for innovation.

Similar to the Business Model Canvas, this level is also divided into nine building blocks: supplies and outsourcing, production, functional value, materials, environmental impacts, end-of-life, distribution, use phase, and environmental benefits.27These blocks are briefly described in the following.

According to Garcia et al. (2020), the functional value describes the “output of the production process being analyzed. This value corresponds to the functional unit used in the LCA analysis conducted on the company” (p.11).28

The material building block refers to the key resources building block from the original Business Model Canvas. It shows how many biophysical resources are used to produce the end product. It is important to note that resources are not only consumed in the production process for physical goods, but also in the provision of services, even if the consumption of such resources is generally lower (e.g., information technology and vehicles).27 However, not all materials need to be listed, rather just the key resources and their environmental impact to provide an overview.

The production building block also extends the key components building block from the original model. This field shows the activities a company performs to generate value creation. For example, this may involve the conversion of materials by manufacturers, but also the provision of IT infrastructure for service providers.27

In the supplies and outsourcing field, all the other activities of the company are listed that were not considered in the previous field but which contribute to value creation. Joyce and Paquin (2016) cite water and electricity supplies as an example, as electricity and water are usually sourced from local suppliers, and companies therefore have little influence over them.27

The distribution field covers the transportation routes during the production process. At this level, consideration must be given to the types of transportation involved, the distance covered, and the weight of the goods to be transported. Packaging must also be taken into account in the transportation processes.27

In the use phase building block, the contribution of the customer to the use of the product is recorded. For example, this may involve the maintenance and repair of the product or the use of electronic devices, as this also generates a demand for materials and energy. Difficulties may arise in this module, as the company’s production process cannot always be clearly separated from the customer’s usage phase (e.g., CEWE photo albums for which content is created by the user).27

The seventh building block is called end-of-life. This should describe what happens to the product after it has been used by the consumer. According to Joyce and Paquin (2016), “this component supports the organization exploring ways to manage its impact through extending its responsibility beyond the initially conceived value of its products” (p.1478).27This includes reusing materials or disposing of the product.27

At the end of the environmental level, environmental benefits and impacts are listed rather than costs and revenues as at the economic level.28 The environmental impact component comprises the total environmental impact, which Joyce and Paquin (2016) also refer to as “ecological costs,” produced by a company.27 Examples include energy and water consumption or CO2 emissions. This component provides the company with an overview of the negative influences of its processes and enables it to take measures to limit them.27

According to Joyce and Paquin, the environmental benefits building block concerns the “ecological value the organization creates through environmental impact reductions and even regenerative positive ecological value” (p.1479).27

8.2 Social Layer

The social level of the Triple Layered Business Model Canvas refers to the relationship between the company and its various stakeholders. This layer in the business model can be used to better balance the interests of the various stakeholder groups and the social impact of the company should also be recorded.27

This level also consists of nine building blocks: local communities, governance, social value, societal culture, end user, employees, scale of outreach, social impacts, and social benefits.23 These are described in the following.

The first building block is social value and describes the extent to which the company creates a benefit for stakeholders. For sustainable companies, according to Joyce and Paquin (2016), “creating social value […] is a clear part of their mission” (p.1479).27

In the second building block, employees occupy their own field on the social level of the Triple Layered Business Model Canvas, as they are one of the most important groups in a company. Various aspects may be considered, such as the number and type of employees as well as significant demographic characteristics, gender, and level of education. This component also offers the opportunity to examine how employee-oriented programs contribute to the company’s success.27

The third building block is governance, which encompasses the organizational structure and decision-making policies of a company.27 According to Garcia et al. (2020), a company can “consider different structure frameworks, such as functional specialization v. unit specializa-tion, privately-owned companies v. publicly traded companies, etc.” (p.13), which also has an impact on the integration of stakeholders into the company and thus the creation of social value. 28

The fourth field of the social level deals with local communities, that is, the social relationships with suppliers and local stakeholders from which both parties can benefit. If a company has several locations in different regions, then it is important that attention is paid to the differing cultural needs and conditions in the area.27

The fifth building block addresses societal culture. This describes the influence of the company on society as a whole, hence, both the positive and negative activities of the company for society are considered.28

The sixth building block is the scale of outreach, which describes the scope and intensity of the relationship between the company and its stakeholders. These can be relationships in which both parties have only a short-term interest or long-term relationships that have local, regional, or global influence.28 The intensity of the relationship describes the extent to which it “addresses societal differences” (p.1481).27

In the seventh building block, end users also occupy their own field at this level. In this area, the extent to which the needs of the end user are satisfied by the product or service and thus improve the quality of life is presented. Consumers are classified as appropriate, for example, according to age.27

Similar to the ecological costs in the environmental impacts field, the social costs are listed in the social impacts field in the eighth building block. Examples of this are fair competition, working hours, or the health and safety of employees. The same examples can also be given for the ninth building block, the social benefits module, as this module describes the company’s activities that create positive social value.27

9 Flourishing Business Canvas Model

The Flourishing Business Canvas model is based on the strong sustainability ontology.29,30 The model is a “collaborative visual design tool that, by providing a common language for an organization’s stakeholders, allows them to effectively work together to describe their enterprise’s business model and imagine future preferred ones” (p.131).31

The tool consists of a variety of elements: There are three contextual systems (environment, society and economy), four different perspectives (process, value, people, and outcomes), and 16 question blocks, which are assigned to the perspectives and contextual systems.32 Figure 7 depicts the Flourishing Business Canvas model.

The process perspective describes where and how a company carries out activities and with what resources. The value perspective shows what a company does now and in the future. The people perspective represents for whom the company performs its activities and by whom the activities are performed. Finally, the outcome perspective shows how the company presents and measures success.31

Elkington and Upward (2016) have formulated questions for each of these 16 blocks. It is important to note that these questions are answered in relation to the different perspectives and contextual systems with which they are associated:31

- Goals: What are the goals of this business that its stakeholders have agreed? What is this business’s definition of success: environmentally, socially and economically?

- Benefits: How does this business choose to measure the benefits that result from its business model (environmentally, socially, economically), each in relevant units?

- Costs: How does this business choose to measure the costs incurred by its business model (environmentally, socially, economically) each in relevant units?

- Ecosystem actors: Who and what may have an interest in the fact that this business exists? Which ecosystem actors may represent the needs of other humans, groups, organizations and non-humans?

- Needs: What fundamental needs of the ecosystem actors is this business intending to satisfy or may hinder?

- Stakeholders: How is each ecosystem actor involved in this business? What roles does each ecosystem actor take? Examples: customer, employee, investor, owner, supplier, community and regulator.

- Relationships: What relationships with each stakeholder must be established, cultivated and maintained by this business via its channels? What is the function of each relationship in each value co-creation or value co-destruction relevant for each stakeholder?

- Channels: What channels will be used by this firm to communicate and develop relationships with each stakeholder (and vice versa)?

- Value co-creations: What are the (positive) value propositions of this business? What value is co-created with each stakeholder, satisfying the needs of the associated ecosystem actor, from their perspective (world-view), now and/or in the future?

- Value co-destructions: What are the (negative) value propositions of this business? What value is co-destroyed for each stakeholder, hindering the satisfaction of the needs of the associated ecosystem actor, from their perspective (world-view), now and/or in the future?

- Governance: Which stakeholders get to make decisions about: who is a legitimate stakeholder, the goals of this business, its value propositions and its processes?

- Partnerships: Which stakeholders are formal partners of this business? To which resources do these partners enable this business to gain preferred access? Which activities do these partners undertake for this business?

- Resources: What tangible (physical materials from one or more biophysical stocks, including fixed assets, raw materials and human beings) and intangible resources (energy, relationship equity, brand, tacit and explicit knowledge, intellectual property, money – working capital, cash, loans, etc.) are required by this business’s activities to achieve its goals?

- Biophysical stocks: From what ultimate stocks are the tangible resources that are moved, flow and/or transformed by this business’s activities to achieve its goals?

- ) Activities: What value adding work, organized into business processes, is required to design, deliver and maintain the organization’s value co-creations and value co-destructions to achieve this business’s goals?

- Ecosystem services: Ecosystem services are processes powered by the sun that use biophysical stocks to create flows of benefits humans need: clean water, fresh air, vibrant soil, plant and animal growth, etc. Which flows of these benefits are required by, harmed or improved by this business’s activities?

These questions can relate to the current status of the business model or to an aspiring business model.31 They are sufficient to fully map the business model. Any company can use this method of mapping the business model, regardless of the exact values that the company embodies or the goals that the company is pursuing.32

If the questions “are answered in light of the organization’s chosen definition of success, and if the answers are informed by our best understanding of how to realize that goal, then the result will be a business model that is more likely to enable the desired outcome”(p.134).31

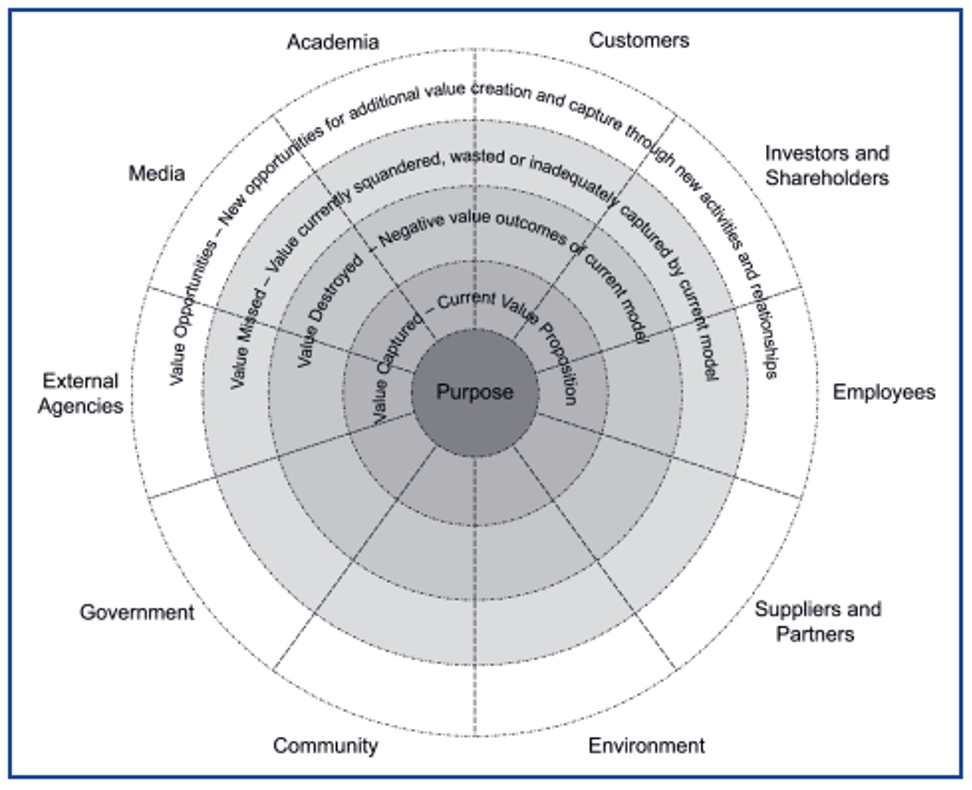

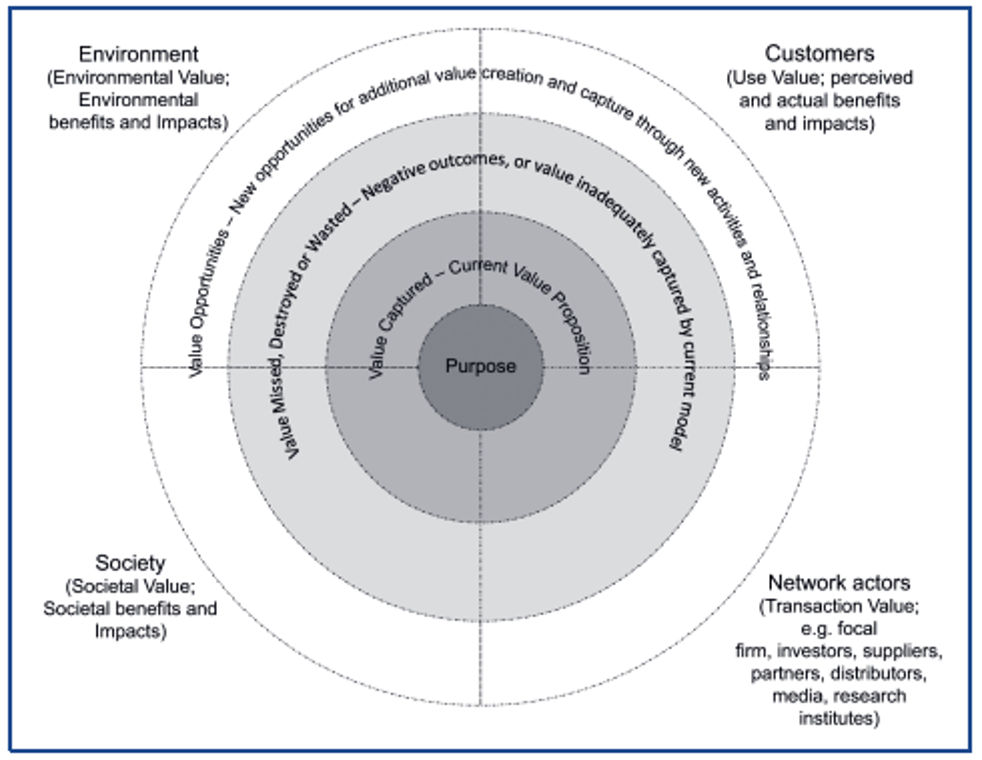

10 Value Mapping Tool

The value mapping tool focuses on the value proposition of a company and follows the multi-stakeholder approach. It should help the company to understand “the positive and negative aspects of the value proposition of the value network” (p.489) and thus help to integrate sustainability.33 The value network refers to the stakeholders who are involved in the process of creating and providing the service. Value conflicts (advantage of one stakeholder, disadvantage of another stakeholder) should be highlighted so that they can be resolved. In addition, opportunities for improving the business model should be identified, with a particular focus on society and the environment.33

A detailed and a simple version of the value mapping tool exist. Hence, a company can decide how much time it wants to spend using the tool and how detailed the map should be.33

In the detailed version, four levels with different values are presented: value opportunities, value missed, value destroyed, and value captured.34 These can be used to identify where there is room for improvement.

The value missed level shows “where actors fail to capitalize on existing assets, skills and resources, where they operate below best practice or where they do not receive the benefits they expect from the network” (p.71).34 Value destroyed represents where the company has a negative impact on the environment or society. Conversely, value captured shows where the company creates positive value for other stakeholders. Value opportunities represent ways in which the company can create additional value.34

The different stakeholder groups are represented in the individual segments of the model: external agencies, media, academia, customers, investors and shareholders, employees, suppliers and partners, environment, community, and government.33

In the simplified version, the value missed and value destroyed levels are combined and the number of stakeholders is reduced to four. Only the environment, customers, society, and network actors are included as stakeholders.33

According to Bocken et al. (2015), the value mapping process consists of four brainstorms. In the first brainstorm, the purpose of the company is discussed.34 This brainstorm also concerns which products and services are offered. In the second brainstorm, the individual stakeholders are considered and the value that is created for them by the company. Positive and negative values are weighed up against each other.34 The third brainstorm examines which values are being destroyed by the company and to what extent the company is missing out on opportunities to generate further value. For example, this may involve wasting materials or capacities.34 The fourth brainstorm concerns how the negative aspects identified can be transformed into positive aspects. It also investigates how further positive value can be created within the network for various stakeholders.34

11 Drivers and Barriers

Although sustainable business models bring many benefits, many companies struggle to evolve their business models through sustainable business model innovation or to implement a sustainable business model.35 Consequently, this chapter aims to identify possible drivers and barriers to the implementation of sustainable business models.

11.1 Barriers

The literature distinguishes between five different types of barriers to sustainable business model innovation:

- Market and institutional barriers

- Organization barriers

- Strategic barriers

- Technological barriers

- Financial barriers

- Resource allocation barriers

These barriers are described in the subsections that follow.

11.1.1 Market and Institutional Barriers

Institutional entry challenges prevent businesses from fully comprehending or adjusting to the laws, social norms, and value systems that influence the culture, processes, and procedures. These challenges exist at various levels within a market and shape the interactions between a company, its customers, and the community.35

Focusing on maximizing shareholder value is a barrier for sustainable business model innovation. Achieving sustainable business model innovation is already a difficult task. If it also has to be profitable, because the focus is on profit maximization and financial performance indicators, this task becomes even more difficult. Companies sometimes refuse to pursue sustainable business model innovations if they have a negative impact on financial performance indicators and therefore also on shareholder value.36

One effect of focusing on maximizing shareholder value is that uncertainty is avoided to achieve financial goals (uncertainty avoidance). According to Bocken and Geradts (2020), “investment decisions inside corporations […] are driven by financial risk avoidance and a low tolerance for uncertainty”(p.7).36

Another effect of the focus on maximizing shareholder value is short-termism. Since rapid returns are to be achieved for the shareholders, investment decisions are influenced by short-termism, while long-term thinking, which is needed for sustainable business model innovations, is neglected.36

11.1.2 Organizational Barriers

One organizational barrier when adapting an existing business model is the leadership gap. Since a business model innovation affects several departments and requires their cooperation to implement far-reaching changes, the entire management level must support the decision and also work together.35 One person alone cannot implement these changes. This can be a particular problem if there are frequent personnel changes at management level.37

Other obstacles can include organizational resistance to change and more complex management and planning processes. A sustainable business model innovation can change existing structures, along with responsibilities and power, which can lead to dissatisfaction among employees and at management level. These changes and possible changes in work processes also require extensive planning, which in turn can inhibit business model innovation.35

11.1.3 Strategic Barriers

Bocken and Geradts (2020) have identified three different types of strategic barriers: functional strategy, focus on exploitation, and institutional focus.36

The functional strategy barrier concerns companies defining clear roles, responsibilities, and authorities within the functional areas to minimize risk and improve efficiency. “To achieve corporate objectives, divisions and support functions each have their own strategy and follow their own strategic plan to reach specific goals” (p.9).36 This focus on their own strategies and objectives within the individual departments of the company has an inhibiting effect on sustainable business model innovations, as conflicts can arise between the departments if their own objectives are not achieved as a result of possible changes.36

The barriers of short-termism and uncertainty avoidance described above also lead to a strategic focus on exploiting existing resources and capabilities (focus on exploitation). This affects the ability to innovate business models, as the company uses the existing business model and focuses on current customer needs.36 By using the existing business model, the strategic focus is once again on maximizing shareholder value, but new skills, which are essential for the development of sustainable business model innovations, are not acquired. Focusing on current customer needs can also inhibit innovation, as customer needs do not always include sustainability.36

Another consequence of short-termism is that strategic alignment is also designed for short-term growth and quick returns, which is why projects that meet these objectives are given higher priority (prioritizing short-term growth). As a result, sustainable business model innovation is neglected, and fewer resources are allocated to these projects. Sustainable business model innovation often requires time and a long-term orientation to achieve success and returns.36

11.1.4 Technological Barriers

Several barriers to sustainable business model innovations can also arise at a technological level. Technical innovations can mean that a company has to adapt its business model accordingly. On the one hand, technical innovation drives a company to change its business model; on the other hand, frequent technical innovations can make it more difficult for a company to implement sustainable business model innovations, as these are usually based on old technologies.35

Another aspect is that the lack of technical know-how can lead companies to rely on familiar technologies that are compatible with the previously integrated business model and thus constrain themselves with regard to business model innovations. One reason for this may be the lack of resource investment in further training.38 Furthermore, the integration of new technologies into the production process which, for example, are intended to reduce the consumption of goods but at the same time generate financial returns, can be viewed critically by employees.35

11.1.5 Financial Barriers

Existing business models usually initially generate a higher profit than a model adapted through business model innovation. This apparent profit tempts managers to allocate more resources to the current business model to generate more profit in the short term.35

Another financial barrier is the high costs of sustainable business model innovations, which present companies with difficulties. The result is that many “organizations, particularly small and medium enterprises, have limited budgets, knowledge, and staff and thus cannot undertake BMI if their resources exceed their capabilities” (p.11).35 The lack of support from banks for the implementation of business model innovations and the uncertain demand further complicate this problem.39 According to Sampene et al. (2023), many sustainable business model innovations therefore fail “because of financial difficulties that most entrepreneurs and organizations face in today’s competitive market”(p.11).35

11.1.6 Resource Allocation Barriers

As stated in the previous sections, the distribution of resources within the company is a central problem in sustainable business model innovation. Resources are critical to corporate strategy and activities, as their efficient utilization leads to profit and sustainability, and improper allocation of these resources can lead to additional high costs, which can cause sustainable business model innovation projects to fail.35

The cognitive barrier identified by Chesbrough (2010), that “the success of established business models strongly influence the information that subsequently gets routed into or filtered out of corporate decision processes” (p.358), leads to the inadequate allocation of resources in the early development phase of a sustainable business model innovation within the company, which often proceeds in a non-transparent manner.37 For example, the utilization potential of technologies is overlooked if they do not directly fit the business model.37 Other aspects may include a lack of resource transparency within the company or the use of outdated tools. 35

11.2 Drivers

In addition to barriers, drivers for sustainable business model innovations also exist. These include the following:

- Organizational learning

- Knowledge management

- Dynamic capabilities

These drivers are further described in the following.

11.2.1 Organizational Learning

One process that can facilitate the implementation of sustainable business model innovations and help to overcome the challenges that arise is organizational learning. “Organizational learning is a critical and fundamental process for processing information and knowledge and changing organization’s traits, behaviors, capacities, and performance”(p.13).35

In sustainable business model innovation, new knowledge must be generated within a company in order to integrate social and ecological aspects into value creation and to implement the often fundamental changes within the company. Continuous learning within the company enables it to respond better to changes in the environment and be more innovative.40 Another positive aspect of organizational learning is the improvement of strategic competence, as managers often underestimate the function of learning in the implementation of improvement.35

11.2.2 Knowledge Management

Another way to promote sustainable business model innovation in a company, which is also related to organizational learning, is the introduction of knowledge management. 35 Knowledge management “is the process of acquiring, converting, disseminating, applying and reusing the knowledge in an organization” (p.364).41 Collective knowledge should be identified and stored within the company to support the company against competition. Knowledge management can also improve the understanding of sustainable business model innovations and the potential competitive advantage, as it can improve the understanding of the relationship between environmental and financial management. It can also help the company with product and process innovations.35

Knowledge management leads to an improved distribution of resources within the company, which is conducive to business model innovation. It can also coordinate the transformation of information into products and services.41

11.2.3 Dynamic Capabilities

Dynamic capabilities represent another driver for sustainable business model innovations.36 They can be defined “as the firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments” (p.516).42 Strong dynamic capabilities make it easier for a company to adapt its business model while maintaining its current level of performance, which is particularly important in a dynamic and competitive business environment.36 Among other things, these capabilities include the ability to recognize opportunities and risks, to exploit or mitigate those opportunities and risks, and to optimize the use of the company’s assets.36

Furthermore, companies with strong dynamic capabilities can also incorporate external resources, service systems, and methods into the design of sustainable business model innovations.35 Dynamic capabilities are therefore essential, regardless of the industry in which the sustainable business model innovation is to be implemented. 35

12 Conclusion

In today’s dynamic and resource-conscious world, sustainable business models are of crucial importance for long-term success. Nonetheless, companies often disregard ecological and social aspects to ensure short-term success. However, sustainable business models not only enable organizations to assume ecological and social responsibility, but also to open up new market opportunities and secure their competitiveness. Accordingly, through sustainable business models, sustainability should be integrated into the value proposition, value creation and delivery, and value capture, based on the triple bottom line.

To integrate a sustainable business model into a company, sustainable business model innovations are necessary. Business model innovation can be achieved through technological, organizational, and social innovations. However, a distinction must be made regarding whether the innovation takes place in a start-up, that is, whether a completely new business model is created, or whether it represents a business model transformation, diversification, or acquisition.

To provide company managers with assistance in transforming business models into sustainable business models, Breuer et al. (2018) developed guiding principles. In addition, Bocken et al. (2014) divided archetypes for sustainable business models into environmental, social, and economic areas, which can be used by companies as a guide for sustainable business model innovations. At the environmental level, the archetypes are to maximize material and energy efficiency, close resource loops, and substitute with renewables and natural processes. The social level comprises the archetypes of delivering functionality rather than ownership, adopting a stewardship role, and encouraging sufficiency. On the economic level, the archetypes include repurposing for society/environment, inclusive value creation, and developing sustainable scale-up solutions.

Various tools also exist for analyzing and restructuring the current economic business model and driving sustainable business model innovations. The classic tool for visualizing and structuring the business model is the Business Model Canvas. A variant of this model is the Triple Layered Business Model Canvas, which includes the ecological and social levels in addition to the economic level. The Triple Layered Business Model Canvas can therefore be used to create sustainable business models. Other tools include the Flourishing Business Canvas model and the value mapping tool.

Nonetheless, despite the significant potential and advantages of sustainable business models, many companies have difficulties with their implementation, which can be attributed to a wide variety of barriers. However, companies must try to overcome these with targeted organizational learning and dynamic capabilities, which can be supported by knowledge management.

Overall, sustainable business models are an opportunity for companies to secure long-term economic success while also contributing to the environment and social responsibility. There are different ways a company can develop to implement a sustainable business model.

References

1 Umweltbundesamt. Beobachtete und künftig zu erwartende globale Klimaänderungen, <https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/daten/klima/beobachtete-kuenftig-zu-erwartende-globale#aktueller-stand-der-klimaforschung-> (2024).

2 McKinsey&Company. Akzente – Nachhaltigkeit erreichen – aber wie?, <https://www.mckinsey.de/~/media/mckinsey/locations/europe%20and%20middle%20east/deutschland/branchen/konsumguter%20handel/akzente/ausgaben%202021/2021/akzente-2-21-gesamt.pdf> (2021).

3 Lüdeke-Freund, F. Towards a conceptual framework of’business models for sustainability’. Knowledge collaboration & learning for sustainable innovation, R. Wever, J. Quist, A. Tukker, J. Woudstra, F. Boons, N. Beute, eds., Delft, 25-29 (2010).

4 Lüdeke-Freund, F. & Schaltegger, S. in Corporate sustainability : managing responsible business in a globalised world 388-411 (Cambridge New York, NY Port Melbourne, VIC New Delhi Singapore: Cambridge University Press, 2023).

5 Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y. & Tucci, C. L. Clarifying Business Models: Origins, Present, and Future of the Concept. Communications of the Association for Information Systems 16 (2005).

6 Zott, C., Amit, R. & Massa, L. The Business Model: Recent Developments and Future Research. Journal of management 37, 1019-1042 (2011).

7 Nosratabadi, S. et al. Sustainable Business Models: A Review. Sustainability 11 (2019).

8 Heinrich, P. CSR und Fashion : nachhaltiges Management in der Bekleidungs- und Textilbranche. (2018).

9 Seddon, P. & Lewis, G. Strategy and business models: What’s the difference? PACIS 2003 Proceedings(2003).

10 Osterwalder, A. & Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers. 1 (2010).

11 Richardson, J. The business model: an integrative framework for strategy execution. Strat. Change 17, 133-144 (2008).

12 Dembek, K., York, J. & Wunder, T. Sustainable Business Models: Rethinking Value and Impact. 131-148 (2019).

13 Bocken, N. M. P., Short, S. W., Rana, P. & Evans, S. A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. Journal of Cleaner Production 65, 42-56 (2014).

14 Geissdoerfer, M., Vladimirova, D. & Evans, S. Sustainable business model innovation: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production 198, 401-416 (2018).

15 Stubbs, W. & Cocklin, C. Conceptualizing a “Sustainability Business Model”. Organization & environment 21, 103-127 (2008).

16 Schaltegger, S., Hansen, E. G. & Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business Models for Sustainability: Origins, Present Research, and Future Avenues. Organization & environment 29, 3-10 (2016). https://doi.org:10.1177/1086026615599806

17 Breuer, H., Fichter, K., Lüdeke-Freund, F. & Tiemann, I. Sustainability-oriented business model development: Principles, criteria and tools. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing 10, 256-286 (2018).

18 Yip, A. W. H. & Bocken, N. M. P. Sustainable business model archetypes for the banking industry. Journal of Cleaner Production 174, 150-169 (2018).

19 Chen, X., Xie, H. & Zhou, H. Incremental versus Radical Innovation and Sustainable Competitive Advantage: A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability 16, 4545 (2024).

20 Boons, F. & Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business models for sustainable innovation: state-of-the-art and steps towards a research agenda. Journal of Cleaner Production 45, 9-19 (2013).

21 Breuer, H. & Lüdeke-Freund, F. Values-based innovation management: Innovating by what we care about. (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017).

22 Fichter, K. & Antes, R. Interaktive Innovationstheorien als alternative „Schule “der Innovationsforschung. Innovation: Theorien, Konzepte Modelle und Geschichte der Innovationsforschung, 61-94 (2014).

23 Lüdeke-Freund, F., Massa, L., Bocken, N., Brent, A. & Musango, J. Business models for shared value. Network for Business Sustainability: South Africa, 1-98 (2016).

24 Bocken, N., Boons, F. & Baldassarre, B. Sustainable business model experimentation by understanding ecologies of business models. Journal of Cleaner Production 208, 1498-1512 (2019).

25 Ritala, P., Huotari, P., Bocken, N., Albareda, L. & Puumalainen, K. Sustainable business model adoption among S&P 500 firms: A longitudinal content analysis study. Journal of cleaner production 170, 216-226 (2018). https://doi.org:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.09.159

26 Bocken, N. M. & Short, S. W. Towards a sufficiency-driven business model: Experiences and opportunities. Environmental innovation and societal transitions 18, 41-61 (2016).

27 Joyce, A. & Paquin, R. L. The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable business models. Journal of Cleaner Production 135, 1474-1486 (2016).

28 García-Muiña, F. E., Medina-Salgado, M. S., Ferrari, A. M. & Cucchi, M. Sustainability transition in industry 4.0 and smart manufacturing with the triple-layered business model canvas. Sustainability 12, 2364 (2020).

29 Upward, A. & Jones, P. An ontology for strongly sustainable business models: Defining an enterprise framework compatible with natural and social science. Organization & Environment 29, 97-123 (2016).

30 Hoveskog, M., Halila, F., Mattsson, M., Upward, A. & Karlsson, N. Education for Sustainable Development: Business modelling for flourishing. Journal of cleaner production 172, 4383-4396 (2018). https://doi.org:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.04.112

31 Elkington, R. & Upward, A. Leadership as enabling function for flourishing by design. Journal of Global Responsibility 7, 126-144 (2016).

32 Upward, A. & Davies, S. N. Strategy Design for Flourishing: A robust method. Rethinking Strategic Management: Sustainable Strategizing for Positive Impact, 149-175 (2019).

33 Bocken, N., Short, S., Rana, P., Evans, S. & Lenssen, M. P. A. I. G. A value mapping tool for sustainable business modelling. Corporate governance (Bradford) 13, 482-497 (2013). https://doi.org:10.1108/CG-06-2013-0078

34 Bocken, N., Rana, P. & Short, S. W. Value mapping for sustainable business thinking. Journal of Industrial and Production Engineering 32, 67-81 (2015).

35 Sampene, A. K., Agyeman, F. O. & Aziz, F. Barriers and Drivers of Sustainable Business Model Innovation: Present and Future Research Perspectives. Macro Management & Public Policies 5 (2023).

36 Bocken, N. M. & Geradts, T. H. Barriers and drivers to sustainable business model innovation: Organization design and dynamic capabilities. Long range planning 53, 101950 (2020).

37 Chesbrough, H. Business Model Innovation: Opportunities and Barriers. Long range planning 43, 354-363 (2010). https://doi.org:10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.010

38 Rizos, V. et al. Implementation of Circular Economy Business Models by Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs): Barriers and Enablers. Sustainability 8, 1212-1212 (2016). https://doi.org:10.3390/su8111212

39 Guldmann, E. & Huulgaard, R. D. Barriers to circular business model innovation: A multiple-case study. Journal of cleaner production 243, 118160 (2020).

40 Ademi, B., Sætre, A. S. & Klungseth, N. J. Advancing the understanding of sustainable business models through organizational learning. Business Strategy and the Environment (2024).

41 Bashir, M. & Farooq, R. The synergetic effect of knowledge management and business model innovation on firm competence: A systematic review. International journal of innovation science 11, 362-387 (2019). https://doi.org:10.1108/IJIS-10-2018-0103

42 Teece, D. J., Pisano, G. & Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic management journal 18, 509-533 (1997).