Author: Marlon Abbas, September 16, 2024

1 Introduction

Corporate responsibility is a highly controversial topic that has been the subject of academic discussion and public debate for some time. Friedmann’s original view that the only social responsibility that companies have is to increase their profits within the legal framework has long been the leading opinion on corporate social responsibility (CSR). This has changed over the last 30 years. The prevailing opinion, particularly among the public but also in academic debates, is that companies should indeed assume social responsibility. There are various reasons for this change of opinion. For example, the market economy system (especially the free market economy) is coming under increasing criticism. In particular, profit maximization and the pursuit of more are seen by the public as something negative. Companies are also facing growing criticism, as the public is increasingly of the opinion that corporate profits are at the expense of society.1 2Here, the concept of Corporate Citizenship (CC) provides an interesting solution to the criticism of the free market economy. Corporate Citizenship gives companies an opportunity to fulfill their social responsibility and benefit themselves in the process. This win-win situation, in which companies benefit themselves by solving social problems, is an interesting addition to corporate engagement. 3 There are various definitions, approaches and even more different implementations of the topic. The understanding of the term is just as varied as its application. Especially in the early 2000s, the term gained great popularity, leading to many scientific contributions and presentations. Due to the lack of a uniform definition and delimitation of the term, there is a scientific debate that is very impenetrable for many.4 In addition, there are only a few detailed textbooks. Often there are only reports by practitioners or disjointed articles in various journals. This work addresses this problem. The purpose of the thesis is to scientifically analyze and present the concept of corporate citizenship. At the end of the work, a summary of the discussion should have taken place, which addresses the most important areas of the term and summarizes them in such a way that it is possible for a reader who is not so deep in the matter to understand the topic with all its complexity. The aim is to make the term and the concept behind it accessible to a broader readership. To this end, the definitions are first summarized and differentiated from one another. The basic fields of action and possible courses of action are then described. Then the most important approaches from the academic discussion will be worked out in order to shed light on the practice of Corporate Citizenship at the end. Classifications, implementation guidelines and best-practice examples are described.

2 Historical Development

2.1 Origin of the Company

The first academic use of the term CC dates back to 1861. At that time, an attempt was made to define the term as it was used in American jurisprudence. The term primarily referred to which jurisdiction a company fell under, and citizenship primarily referred to the owner. Thus, this term was used in the legal field and does not have as much to do with today’s understanding of the term. However, the concept and understanding of a company in its form goes back to antiquity. Roman law contains evidence of the existence of companies and also the legal understanding. This is also where the involvement of companies in their social environment begins. Companies were often founded in the Roman Empire in order to engage in social activities, such as supporting poorhouses and orphanages, as well as hospitals and political associations. In the Roman Empire, companies were therefore already firmly linked to their social environment. Even in the late Middle Ages, companies were founded almost exclusively for social and religious purposes. In the British Empire, for example, the British Crown and Parliament had the sole right to establish companies or grant the right to do so. The companies that were founded during this period were almost exclusively for religious or social purposes. It was not until the early modern period that the British Crown and Parliament began to use corporations for the management and trade of the new colonies. This changed the purpose of the companies from social functions to trade, production and services. 6,7

2.2 Social commitment in the modern era

Nevertheless, the social commitment of companies is not a phenomenon of modern times. There are examples of social commitment, as described by today’s corporate citizenship, dating back to the late 19th century. For example, Macy’s, the largest department store operator in the USA, is known to have donated to orphanages as early as 1875. Siemens, a large German industrial company, also built a children’s home in 1911, for example, having already set up a company pension, widows’ and orphans’ fund in 1872. These are just two of many examples of the social commitment of companies, which show that social commitment was already present at this time. Due to the two world wars, which caused social problems, and the growth of companies in the early to mid 20th century, companies were increasingly seen as institutions with social responsibility. This debate gave rise to the term corporate citizenship.8,9

2.3 Origin and development of the concept of corporate citizenship

The first academic use of the term CC in today’s economic understanding was in the late 1950s, where the academic debate on corporate social responsibility originated. The debate on the social responsibility was mainly conducted in the 1960s and 1970s. However, the debate took place almost exclusively in academic circles and then died down again. It was not until the end of the 1990s that the topic was taken up again and really exploded in the early 2000s. During this time, several CC journals were founded (such as the Journal of CC [2001]) and institutions associated with the term CC (such as the Centrum für CC Deutschland). In 1997, the first report by a company was published under the name CC. In 2004, the term has been used the most to date. However, it should be mentioned that the term CC has been used somewhat more in the media than the term CSR. In scientific publications, however, this is the other way around. There are significantly more publications on the term CSR than on CC. Backhaus-Maul explains the rapid spread of the term in the 2000s as a reaction to the need for orientation on the issue of corporate social responsibility at the time. CC served as a response to criticism of the market economy and companies, providing orientation and security for companies. Many CC journals are no longer active. For example, the popular Journal of CC has not published since 2017. Reports under the name CC Report, such as those from Siemens, are now published under a different name. Schrader believes that academic interest in the promising concept of CC has waned considerably. This could be due to the fact that CSR and other terms are less tangible and can be interpreted more freely than corporate citizenship. In his opinion, the term continues to lose meaning or is used as a collective term for voluntary corporate engagement. This is also shown by a literature review, which found that the majority of the primary literature was published in the early 2000s. A few sources are cited by far the most, all of which date from this period. According to their study, CC is also stagnating in the literature. This could also be related to the inactive journals, which were very popular for publishing literature. Overall, however, they confirm Schrader’s assessment that interest in CC is declining.8,10 4,6,11

3 Definition

There are various definitions and opinions in the literature on the term corporate citizenship, all of which relate to the question of social responsibility. However, the authors disagree on several points. There are various approaches to differentiating the term from other similar terms in the field, such as CSR or corporate governance. There are also different approaches to the question of how far responsibility extends and to whom responsibility applies. Essentially, the discussion can be reduced to three definitions. This chapter provides an overview of the various approaches and definitions of the term corporate citizenship. However, it should be noted that only a few authors have actually dealt with the term CC in order to try defining it. A differentiation from other terms is also rarely made.4

3.1 Extended view of Corporate Citizenship

Many authors use CC synonymously with corporate social responsibility. In this definition, which is the most widely used internationally, corporate social responsibility is part of the duties of a corporate citizen both in and outside the core business. Archie B. Carroll, an author with many articles on the subject of corporate responsibility, defined CC in 1998 in the same way as he described corporate social responsibility in 1979. According to Carroll, a corporate citizen has four responsibilities towards society, some of which are derived from the responsibilities of private citizens towards society. The responsibilities are of an economic, legal, ethical and philanthropic nature and relate both to the core business and to voluntary commitment outside the company’s activities. 12

The economic responsibility of a corporate citizen is to make enough profit to be able to survive. But it is not only the corporate citizen that must be able to survive. A good corporate citizen must make enough profit so that, on the one hand, investors can make a profit from their investment and, on the other, the company’s stakeholders are assured that the company will continue to provide products/services and jobs in the future. This responsibility is analogous to the responsibility of a normal citizen to provide for themselves and enough income so as not to become a burden on society. Furthermore, it makes little sense to talk about social responsibility if the company cannot survive in the long term.13

The next responsibility is compliance with legal requirements. This responsibility also arises, even more clearly than economic responsibility, from the responsibility of a good citizen to be law-abiding. The laws result from the requirements of the respective states and are to be seen as a regulatory framework for economic activity. Overall, government regulations are a controversial topic, especially in countries that historically have a free market economy, such as the USA. However, it should be emphasized here that laws have often been used where the market has failed, such as in the case of unsafe products or environmental hazards. Accordingly, companies that want to be a good corporate citizen should follow these legal requirements even if they were not. 13

The third responsibility is to act ethically and morally. Companies should make as much profit as possible, but from an ethical and moral point of view. This responsibility arises from the assumption that compliance with legal requirements is only the absolute minimum of ethical and moral action. This means, on the one hand, that the current legal requirements are not sufficient to actually protect the various stakeholders and, on the other, that the law is outdated, as it always takes a certain amount of time for moral standards to become law. Furthermore, not all problems can be solved by laws. For these reasons, it is necessary for good corporate citizens not only to obey the law, but to go beyond it. Business ethics is about the company developing a code of ethics and then enforcing it in all areas of the company. It is important to note that the company management should act as a role model for the entire company, but also for the population. In doing so, companies should be guided by normative ethical considerations and thereby pursue the question of what should be done rather than what is done. After all, just because many people do something does not mean that something is right. Accordingly, companies should always ask themselves whether their actions are really morally justifiable. Carroll also emphasizes that it is important not only to do the right things, but also to be an ethical citizen. In other words, as a company, you not only do fair and honest work, but are also fair and honest yourself. 13

The fourth and final level of CC is philanthropy. Overall, this is about participating as a company in the problems of society and providing solutions through financial resources or employee involvement. In his view, good citizens should give something back to the society in which they operate. In his opinion, it is important that companies meet the demands of society in terms of charity and act accordingly.13

A distinction must be made between the various responsibilities. The first two social responsibilities (economic and legal) are an important prerequisite for the long-term economic work of the company. Without them, the company cannot survive in the long term. The third responsibility, i.e. ethical behavior, is expected by society. To be seen as ethical, or not to be seen as unethical, the image of the company is also heavily dependent on the three responsibilities. This is also the major difference to philanthropic responsibility (i.e. corporate citizenship). Although society wants companies to be socially committed, it does not condemn companies if they are not socially committed. If, on the other hand, a company acts illegally or unethically, this has a negative impact on its image.14

This is how many authors define corporate citizenship, such as Carroll. Maignan and Ferrel, for example, described CC as a model that describes the extent of the economic, legal ethical and discretionary responsibilities of companies. Similarly, Andriof and McIntosh, who described CC as corporate social responsibility, use the term synonymously with CSR. As just shown, the definitions of the terms differ, but they mean the same thing. Using CC synonymously with corporate social responsibility creates some problems that are not conducive to the concept itself. For example, many authors in the debate on corporate social responsibility have a certain point of view, such as Carroll, who has been actively involved in this discussion for some time, and then use this term to solve new problems. As a result, CC is presented as a new term for an old construct with new problems and thus does not generate any added value for the discussion on corporate social responsibility.15

3.2 Limited definition

The limited definition ties in with the broad definition, but is, as the name suggests, more narrowly defined. This definition is the original version of CC and is particularly widespread in Germany. In 1991, Carroll defined CC merely as the fourth level (philanthropy) of corporate social responsibility and not as the entire pyramid as in the later definition from 1998. According to Carroll, a company must actively strive to improve the well-being of society as a good citizen. The company can use operational resources (corporate giving) or employees (corporate volunteering). Despite its international popularity, this definition is not precise and leaves a lot of scope for interpretation. Habisch, a German representative of this definition of CC, defines the term CC more precisely. He defines four characteristics of corporate citizenship. The first characteristic he explains is that companies get involved to help solve relevant social problems. This is the basic characteristic of corporate citizenship. For example, companies can expand the resources of a charitable organization, thereby participating in the solution of a charitable problem. The second characteristic is that the involvement must be with external partners such as educational or cultural institutions. These can be a wide variety of organizations that bring a solution to the social problem. There are basically three different types of partners available (public institutions, private non-profit organizations and other companies). The corporation is important because, on the one hand, the partner brings the necessary skills and solution potential for the social problem and, on the other hand, it increases the credibility and perspective of the project. The third feature is that the company provides the partner with various operational resources such as funding, employees or access to logistics, networks and information. A basic distinction can be made between corporate giving and corporate volunteering. Corporate giving primarily includes donations and sponsoring. Donations and sponsoring can be of a financial or material nature (products, services, information), whereby sponsoring, unlike donations, involves a service in return (often in the form of advertising). In corporate volunteering, the company makes its employees available. Employees can be active in projects initiated by the company or in their own projects that are merely sponsored by the company. The last characteristic Habisch recognizes is that the company itself must achieve a benefit through this commitment. It is important for credibility that the benefit to the company does not significantly exceed the benefit to society. However, this economic benefit for the company is important to ensure that the commitment is secured in the long term and is not discontinued in the next crisis. In addition, the projects are often only beneficial to society after some time, which is why a long-term commitment is important. According to Habisch, there is not only a positive corporate image, but also advantages, for example in the area of human resources through higher employee satisfaction or in marketing through increased customer loyalty.14, 16

3.3 Based on the concept of citizenship

Finally, a more theoretical definition follows, which is based on the basic concept of a citizen. According to Crane/Matten/Moon, many authors use the term CC without considering the basic idea of a citizen as a member of a society. Citizenship is a concept that defines the rights and duties of an individual in a community. This is precisely what is unclear in the debate on corporate social responsibility. For example, what responsibilities and to whom companies are responsible is uncertain. This is where the republican definition of a citizen could help. According to Petersen, a citizen according to the republican definition is a member of an organized state collective. Together with the other citizens, the citizen bears responsibility for his organized collective. The concrete responsibility is then expressed in the duties of each citizen. If companies see themselves as citizens, they also bear responsibility for society. Accordingly, as citizens, companies should also take care of solving social problems, just as it is the duty of a “normal citizen”. For the republican citizen, increasing the common good is the highest goal. Accordingly, the assumption of social responsibility must not be practiced because of the win-win scenario, but must be seen as a goal. However, as companies have to survive in the market economy, they should not focus on this alone. However, companies should consciously search for and utilize win-win potentials. The goal of assuming social responsibility also means avoiding economically lucrative activities if this harms the common good. The republican concept of citizenship also includes participation in politics. Here, too, companies should ensure the highest goal of increasing the common good through lobbying.4,15,17

Matten and Crane go one step further. In order to achieve the highest goal, companies sometimes take the place of the state and take on civil, political and socio-economic tasks. In doing so, companies take the place of the state, for example in areas that the state can no longer fill or where companies do a better job. In addition, companies could assume responsibility in areas where the state is not involved. In the 19th century, for example, companies took over the education of children because the state had not yet assumed responsibility in this area. Globalization also makes it easier for internationally active companies to solve international problems than states, such as climate change, the enforcement of human rights and working conditions. While international companies have influence over suppliers or their own locations, states cannot exert any direct power over other states. For example, lobbying or the influence of companies could be used to achieve something in politics to improve the common good. 4,15

3.4 Differentiation from other terms

As already mentioned in the definitions, not only are there hardly any distinctions from CSR, but the terms are often used as synonyms. However, there are different distinctions that are applied depending on the definition. For example, the narrow definition of CC does not include CSR. In this case, CC is regarded as a small part of CSR. CC is independent of the core business and is concerned with the use of profits. In this understanding, CSR is the assumption of responsibility, including in the core business. In the broad definition, CSR only describes the assumption of responsibility in the core business. CC, on the other hand, also describes the assumption of activities for the common good and is therefore the overarching term. Ultimately, the distinction depends on the definition of the terms. 4

Corporate philanthropy describes donations by companies for charitable purposes. This merely involves donations for philanthropic reasons. CC, on the other hand, describes the responsibility of companies towards society and how this can be implemented with a benefit for the company. 3

Strategic Corporate Philanthropy also does not come close to the definitions of CC, despite the broader scope of its activities (not only donations, but also sponsoring and cause-related marketing) and strategic considerations. It lacks the justification of citizenship and responsibility towards society on which the activities are based.3

3.5 Summary of the definitions

The CC model and the academic debate can be summarized in three definitions. The broad definition sees CC as a model in which companies must fulfill their social responsibilities (economic, legal, ethical, philanthropic) both in their core business and beyond their actual business activities. The limited definition, on the other hand, sees CC as the responsibility of companies to solve social problems independently of their core business in accordance with a good citizen and to create win-win situations in the process. These two definitions are difficult to distinguish from one another (see Table 1). The civic-derived definition sees CC as a model that, based on the concept of citizenship, ascribes to the company the duty of every citizen to see the increase of the common good as the highest goal and to solve social problems in order to achieve this goal. Although these definitions are all different, they all contain the core reference that companies have a responsibility as participants in society to help society by solving its problems. Companies are not to be seen as the saviors of society, as a large part of society is supported by the state and “normal” citizens, but they still do their part. The spread and adoption of the definition depends on the state, the economic model and the history. 4

4 Corporate Citizenship commitment

4.1 Forms of Corporate Citizenship engagement

There are various forms of social engagement. For example, the company can support organizations financially or with material donations, enter into sponsorship agreements or ensure the involvement of its employees (see Figure 2). These forms of engagement are described and explained in the next chapter.

4.1.1 Corporate giving

Corporate giving refers to the provision of goods and services by the company free of charge for charitable purposes. Corporate giving makes up a large part of CC commitment. Financial and material resources can be given or operating resources and premises can be made available. Corporate giving can be divided into three different instruments. These are corporate donations, sponsoring and corporate foundations.

4.1.1.1 Donation

Donations are the most traditional form of corporate citizenship. In Germany, for example, 80% of companies make donations according to a study by the Bertelsmann Foundation. Donations are defined as the selfless giving of money, material resources, company services or information. A donation is voluntary if there are no legal or other obligations that would force the donation. Furthermore, the donation is free of charge, i.e. without any agreed consideration. As soon as there is a consideration, such as advertising by the charitable partner, it is no longer a donation but a sponsorship. It is also important to mention the tax benefits for the donor. Another advantage of corporate donations is the low cost involved. However, it should be noted that without a concept, it can lead to image damage. At some point, the organizations could take the donations for granted and failure to donate could be seen as very negative by third parties. If a company donates to a tax-privileged organization, there are ways to save taxes. The donations can be deducted from the total amount of income (maximum 20% of the total amount of income). However, there is also a hurdle for small companies when it comes to tax exemption, as the law on donations is quite complicated and subject to many conditions. In addition, it is also important that the company has as little connection as possible with the organization so as not to be guilty of embezzlement. 18-20

4.1.1.2 Sponsoring

The difference with sponsoring is that the companies conclude a contract with the organizations in which a consideration is agreed. The company then receives something in return for its donation. The consideration is often in the form of communication services. This allows the company to present itself to the public and advertise its products, for example. It depends on the extent to which the communication is designed. A distinction can be made between different forms. Cultural sponsorship involves supporting people or organizations with an artistic background (e.g. museums or theaters). In return, the sponsor is named as a benefactor (for example on the tickets or in the program booklet), which improves the image. In sports sponsorship, on the other hand, the company supports athletes or sports clubs in order to utilize their reach and level of awareness. Sporting events with a high level of media interest are particularly suitable for this. The consideration is then provided, for example, in the form of jersey advertising or presentation of the sponsor on tickets or banners. The final form of sponsorship is social sponsorship. Social and charitable commitment is important here. Social sponsoring includes, for example, environmental sponsoring and university sponsoring. The focus here is on social commitment. With sponsoring, the company is rewarded with tax savings in a similar way to donations. The company can deduct the expenses either as operating expenses (fully deductible) or as a donation (partially deductible). The full deduction as a business expense is attractive for the company, as services and transfers of use can also be deducted. For organizations, on the other hand, it is even more complicated, which also presents hurdles for sponsoring. For example, tax relief depends on the type and nature of the consideration. 19,20

4.1.1.3 Foundation

The third instrument of CC is the corporate foundation. This is a very long-term and in-depth commitment by companies. The foundation is defined as a permanent form of organization that uses the resources made available to it for charitable purposes. The corporate foundation is based on three basic elements. The first is the foundation’s purpose. This is charitable and strongly influences the identity of the foundation. It also defines the foundation’s program and projects. The second basic element is the foundation’s assets. The foundation’s purpose is pursued from the income generated by the foundation’s assets. The foundation’s assets are invested in such a way that the foundation’s purpose can be achieved on a long-term and sustainable basis. However, there are also variants in which the foundation’s assets are increased at certain intervals. The last basic element is the foundation organization. This establishes an organ structure in order to be able to act. Foundations usually consist of two bodies, the foundation board and the foundation council. The foundation board represents the foundation and manages the business, while the foundation council makes the most important decisions and monitors the board. Donations to foundations are also tax-privileged in many countries, as is the case with sponsoring and donations.19

4.1.1.4 Cause-related marketing

Cause-related marketing is a form of corporate giving that is still relatively little used. It is seen as a commercial partnership between companies and charitable organizations in which a product or service provides a charitable benefit. Companies often advertise that when a product is purchased, part of the purchase price is invested by the company in charitable causes. The partnership is beneficial for both sides. The companies benefit from product sales, image and information from the partnership, while the non-profit partner benefits from the money, awareness and information from the partnership. It is important to note that companies are not necessarily acting for charitable purposes, but rather for marketing reasons. Nevertheless, it offers a real win-win situation for everyone involved. Companies, organizations and customers all benefit from CRM. The companies benefit from the very positive perception of customers via CRM. Customers are positively influenced by CRM in their purchasing decisions, their view of the company and the campaign. The charitable organization benefits from the company’s financial contributions and the customers can say about themselves that they have participated in the charitable campaign. So there is a benefit for all parties if CRM is used correctly. 20,21

4.1.2 Corporate volunteering

CC is the other major part of charitable corporate involvement. Here, the company is only indirectly involved. Instead, the company’s employees are active in the social environment, which the company merely supports. The partner benefits from the staff and their skills and capabilities. This instrument offers the opportunity to make the company’s commitment more effective. Mutz divides corporate volunteering into five different forms. The first form is the so-called project days. Here, charitable projects are carried out by the company’s employees on one day. One example would be the environmental day, on which employees are given time off to clean up parks. This type of corporate volunteering is quite non-binding and is designed for one-off, small-scale projects. 22,23

The next form consists of events, where a group of employees takes on a social task. The event can last from several days to a week. The social task can range from renovating playgrounds to preparing cultural events. The employees also take on the preparations that need to be made in advance. It is important that the project is fully completed during the event period. 23

The third form is project weeks. Here, employees are released from work for an entire week to work in social institutions. The employees help in volunteer centers to carry out charitable work. The employees provide more support through their manpower than through their skills. It is important that the social institutions fit in with the company image and the needs of the employees. 23

The next form of corporate volunteering is regular leave of absence. In this case, employees have a monthly or annual time concept that they can use for civic engagement. The areas are either selected and prepared by the company or by the employees themselves. The first option assures the company that the commitment is in line with the company’s values. The second option, on the other hand, gives employees more independence and responsibility. This means that employees are closer to the projects. 23

The last form is secondments. This is a one-off, long-term commitment. This form involves sending employees to similar areas in which the company is active. This is a great way for employees to contribute their skills to charitable work. Mutz cites the example of sending long-distance travel agents to development organizations in Asia or Africa. The advantage for the employee/company is to find their way in a new environment and to be able to apply their knowledge to new, unfamiliar problems. The situations involved can only take place in “real life” and cannot be simulated in seminars. However, the most important step for the employee only begins after the actual project. The knowledge and social skills gained must be transferred to everyday working life so that the employee also benefits from the secondment in the long term. One important restriction still needs to be made with regard to secondments. In order to be integrated into CC instruments, the commitment must be made in a non-profit area. For example, assignments with suppliers or customers are also part of the secondment, but have nothing to do with corporate citizenship. 23,24

In all forms, it is important that the commitment fits in with the company’s values. In addition, not all areas of society are suitable for employee involvement. A hospice, for example, is not suitable. In addition, many areas are often not suitable due to the short commitment. So-called social tourism is rejected by non-profit organizations for this reason on the one hand and due to the lack of meaningfulness of the commitment on the other. This is because short stays cause many costs and have little benefit for the organizations. For a positive outcome, it is therefore crucial that the companies/employees come up with a concept and a strategy beforehand and then plan and implement the engagement. 23

4.1.3 Special forms

There are also some special forms in which corporate giving and volunteering overlap. One of these special forms is the public-private partnership. Here, companies and public institutions form a partnership to realize a joint project. There are four requirements for a public-private partnership to occur. Firstly, the project must be in line with the principles of the respective public institution. These projects are only accepted if the institution sees this as its area of responsibility and also agrees with the company. The second characteristic is the planning of common goals. The goals of the company and the goals of the public partner do not necessarily have to be the same, but they must overlap in such a way that they support each other. The next characteristic is the company’s contribution. The company must make a significant contribution to the project, regardless of the CC instruments used. The private partner covers at least half of the costs. The final characteristic is that the company’s involvement must be independent of its core business. This is because the partnership should not provide the company with help for its core business, but rather be a collaboration for charitable purposes. The partnership can take various forms. The first form describes cooperation between companies and public partners in development work in poor countries. The second form, which is becoming increasingly widespread, describes a model in which the state assigns public tasks to companies, as defined by Matten/Crane/Moon (Chapter 4.3). The tasks can range from infrastructure maintenance (e.g. operation of a road tunnel) to the operation of state schools. However, a distinction should be made here as to the extent to which the second form can still be declared as CC, as the companies operate the state tasks out of economic interest. Although there are also benefits for the company through CC, these are only indirectly expressed in economic terms. If a private-public partnership is to be regarded as CC, the project must not generate direct economic returns for the company, but should be of a non-profit nature 25

Another special form is the Community Advisory Panel. This is a long-term, regular discussion forum for dialog between companies and other representatives of the local region. It always makes sense to set this up if the company’s work could cause potential conflicts with the local community. However, the focus is not only on the company itself, but also on other problems in the local region, which are then discussed with a view to finding a solution. The Community Advisory Panel can be seen as a special form of corporate volunteering, as company employees are seconded here to discuss social problems. 26

4.2 Areas of commitment

The areas in which CC is undertaken are very diverse, but should be chosen carefully. For one thing, the commitment to a business benefit must fit in with the company’s values and identity. And the other important point, which is reflected in some areas in particular, is that the company should solve a social problem. For example, companies may be involved in charitable activities, but they are not solving a social problem. Not only is this not in the spirit of corporate citizenship, it is also not an efficient use of corporate resources. Particularly in the areas of sport and healthcare, a distinction must be made as to whether a social problem is actually being tackled. For example, companies can donate resources to cancer patients. This is certainly a good thing, but does not necessarily address a social problem. 27

4.2.1 Education sector

The education sector offers many opportunities for companies to get involved. This is because the education sector is often affected by structural problems that companies can solve as part of their responsibility as citizens. In Germany, for example, there are significantly fewer students than in other countries, it has the lowest number of nursery and elementary school teachers per child in an international comparison and overall spending on education is also below the international average. There are many opportunities for companies to get involved. For example, there is the Boston Consulting Group’s business@school initiative. In the first step, consultants volunteer to teach pupils about companies. In the second step, the students then develop business ideas, which are then evaluated in a competition. Thanks to their practical approach, the consultants have many opportunities to impart knowledge that schools often lack. If we go back to the problems in Germany, the progress of the project becomes clear. The young people acquire additional qualifications by participating in the project and the teachers also take part in the project’s training courses. The project then addresses the problem of insufficiently qualified specialists by awarding certificates. This example shows that the theory of the corporate citizen, who takes on the tasks of the state, is particularly relevant in the education sector. 28

4.2.2 Culture

In view of the growing importance of corporate citizenship, private cultural sponsorship by companies has become increasingly popular. However, as it is only the third most important source of income for cultural institutions (behind commercial income and state funding), companies cannot claim to fill the gaps left by the state. The volume of funding is simply too small for this. Private cultural funding creates an important link between culture and business, which can only be maintained in the long term if the intention is good. Such a link is particularly important for cultural institutions that appeal to a small clientele and are cost-intensive. Private cultural sponsorship not only facilitates access to such institutions (e.g. cheaper tickets), but also promotes them in such a way that certain art forms whose popularity is declining can continue to operate in the future. In return, the company can also receive advertising (e.g. company logos on tickets) and also create a good image.29

4.2.3 Environment

In the era of climate change, it is possible for companies to change their processes in such a way that they have a positive impact on climate change and sustainability. Climate change, environmental pollution and water wastage in particular are major social problems that also receive a great deal of media attention. This often also has the advantage of promoting a very positive image. When it comes to the environment, it is often questionable whether the commitment is actually corporate citizenship. The Rail & Fly method has become popular with air travel providers. Travelers can travel to their flight by train free of charge. However, Rail & Fly is part of the core business and solves the social problem of excessive CO2 emissions, but is actually more of a sales strategy designed to persuade consumers to travel by air. Nevertheless, there are also many opportunities for actual CC engagement 30

4.2.4 Health

In the past, it was not possible for companies to enter into a relationship with the healthcare system for a long time because it was a closed system. The closed system was created by the fact that state aid was so strong that the healthcare system was able to remain financially stable. Therefore, there was no need for economic support and it was not wanted. However, such support was not only not wanted for financial reasons, but also because there was concern about the loss of therapeutic freedom. Nevertheless, we find ourselves in a time in which a lack of resources and manpower is becoming an ever greater problem. This is why the popularity of economic support is steadily increasing. CC is an important part of strengthening the healthcare sector. This empowerment can be expressed through sponsorship of medicine or donations to specific medical facilities. However, while corporate support can be helpful, it is not always desirable. Donations and sponsorship can lead to system changes that are not necessarily beneficial for the healthcare system. Furthermore, not all corporate involvement can be classified as corporate citizenship. A distinction can be made between project-related and system-related commitment. Project-based engagement is about supporting specific projects, while system-based engagement aims to bring about long-term change in the system. While the project-based system is about individual, large-scale projects in which even small companies can be of great help, the system-based system requires such intensive support that only medium-sized and large companies can provide it. Cooperation between companies and the healthcare sector is not easy and must be handled with care. For example, there are often sensitive issues in healthcare, such as death. There are many elements that need to be considered, such as communication, the individual and their rights. Such cooperation is complicated and time-consuming.27

4.2.5 Youth and family

Working with young people is an important part of society, because young people are the future of society and companies. Solving social problems among young people is an important task in order to maintain a functioning state in the future. Cooperation between youth and business was initially rather undesirable, as it was believed that only parents and the state were capable of providing for the upbringing, education and social integration of children, but nowadays companies have many opportunities to give young people a good chance. Companies can provide support in areas such as health and nutrition, violence and intolerance, qualifications for training and work, socio-cultural infrastructure (e.g. rural regions) and demographic change and emigration, thus helping young people, society and themselves. After all, young people are the employees of the future for companies. However, we should not only think about the future, but also about the present. The labor shortage is present now and must be counteracted. This can be achieved by the company using CC in family matters. As the compatibility of family and career is rather limited, companies have started to find solutions to the problems. For example, companies have to arrange individual childcare so that employees do not have to give up their careers. In addition, flexible working hours are made possible, which leads to an increased sense of well-being among employees. Employee participation increases and there is a lower frustration and sickness rate and a reduction in the number of experienced employees. Overall, both sides benefit greatly from CC, resulting in a win-win situation. 31,32

4.3 Research findings on Corporate Citizenship engagement

The CC-Survey 2018 is one of the few broad studies on corporate citizenship. It asked 120,000 companies in Germany about their commitment, 80% of which completed the questionnaire in full. Companies of various sizes in all parts of Germany were surveyed. The results attest to the widespread commitment of the companies. The first question was whether companies had become involved in the last three years. 80% of companies have donated money and 70% have donated material resources. Donations of use (53%) and free services (54%) are also widespread. This shows that corporate giving was already in place at many companies. At the same time, the response to regular corporate giving is much poorer. Only half of the companies that were involved in the various forms were also involved on a regular basis. Corporate volunteering is also quite well represented, with 56% taking time off work and 27% helping out on specific occasions. However, regular involvement is even lower than for corporate giving, at just 16% (employee time off) and 7% (helping out on specific occasions). It should also be noted that 61% of large companies (more than 10,000 employees) carry out their own social project, while the average for all companies is only 7%. Thus, there are differences in the forms of action depending on the size of the company. In terms of the areas in which companies are involved, sport dominates with 58%. This is followed by education (46%) and social affairs (33%). It should also be noted that church and religion (21%) are supported to a similar extent as the environment (18%). Here, too, there is a decisive difference between the large companies and the average. For example, 75% of large companies are involved in the area of science and research, while this area is only supported by 14% on average. A similar picture can be observed in the international sector. The authors conclude that the smaller the company, the closer it is to its own environment. When it comes to the question of who is the company’s most important partner, local associations are by far the most widely represented (48%). This is followed by educational institutions (21%) and then business and charitable organizations (14% and 13%). 18

The international CECP study “Giving Numbers” from 2023 provides similar results, but there are still differences. This study surveyed large companies, primarily from the USA. It indicated that 47% of donations are monetary donations from the company, 33% are monetary donations from a foundation and 20% are donations in kind. In terms of areas of commitment, education, the environment and healthcare dominate. Two questions were asked in the study. The first question was which of the areas was the most important area of engagement. Here, education (28%) was the strongest. This was followed by Community & Economic Development and Healthcare (both 20%). When asked about the top four areas of engagement for companies, Community & Economic Development and Healthcare (both 38%) were the most important. These were followed at some distance by Education, Higher Education and Environment (all 25%).When comparing the research results from Germany, it can be seen that there are different social problems in different parts of the world that are tackled with different levels of importance. It should also be noted that the studies asked different questions. The same applies to the definition of the terms CC and CSR. The studies may use different views of the terms and therefore differ. Nevertheless, the differences in the results are interesting and show the different social problems in different parts of the world.33

5 Corporate Citizenship discussion

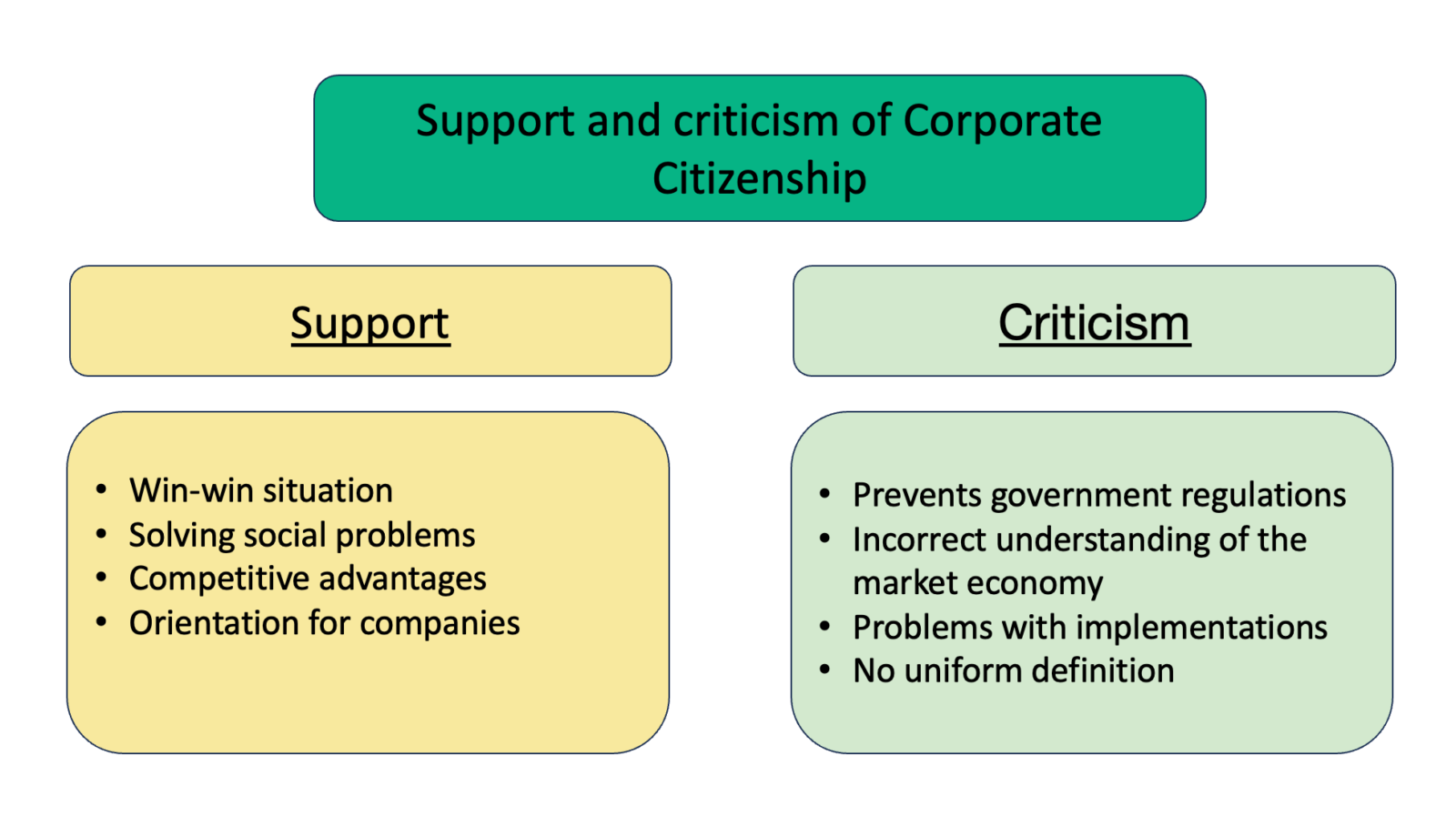

In the discussion about corporate citizenship, the benefits for society and for the company are often addressed. There are many different advantages for companies in particular. However, it is precisely these that are often criticized (see Figure 3). This chapter is intended to provide an insight into these two important topics of the discussion.

5.1 Benefits of corporate citizenship

It is quite obvious that non-profit organizations benefit from corporate citizenship. However, it is less clear what the benefits of companies are. There are many articles on the benefits of companies and some authors even see it as one of the characteristics of CC that companies benefit from it. In the debate about CC, the question of the benefits of companies is a much-discussed topic. Many authors are of the opinion that CC has added value for the company and that it is actually worthwhile. Surveys have shown that the public is critical of companies. The prevailing opinion is that companies act primarily out of self-interest. All companies therefore face this problem. From an ecological point of view, it would therefore make sense to leave social commitment to other companies, save money and benefit from improving the image of the entire industry. However, the benefits of CC exceed the pure image gain of companies (see Figure 4). 16,34

5.1.1 Business case

The benefits for companies are a much-discussed topic when it comes to corporate citizenship. However, it is part of CC and in some cases is the reason for this commitment in the first place. In addition, the benefits for companies ensure that companies make a long-term and conscientious commitment. Without this benefit for the company, companies can only afford to get involved in good economic times and with a healthy financial company structure. Accordingly, it is the benefit that secures the commitment in the first place. Globalization means that companies are facing ever greater and tougher competition. Companies must therefore be a special attraction for stakeholders in order to convince them to buy the product or work with the company. Social commitment can help with this. 35

Habisch and Schmidpeter cite relationship management as the first point. Contracts with partners are a very important basis for companies’ business activities. Due to the dependency on these partners for raw materials, for example, relationships with partners are an important matter. For example, contracts are often concluded incompletely. This means that certain factors, such as the quantity or the time period, can still be adjusted. A company must therefore maintain a good relationship with its partners. CC can help here by demonstrating the company’s cooperation skills, reliability and credibility by working with partners in charitable activities. Through appropriate corporate communication, the image of a trustworthy, cooperative partner can be created, which can then help with economic relations. 35

The next point is the acquisition of information. This deals with the different views and perspectives of customers, partners and political decision-makers and is shaped by their experiences, values and cultures. This information is of crucial importance for a company’s business activities. Knowledge can often only be obtained by participating in these relationships. For example, a company needs information about what product features the consumer wants. The product developer, for example, identifies other product features as being as central as the consumer. However, since it is ultimately the consumer who decides whether to buy the product, information is of central importance for the development of a product. Through CC commitments, companies can come into direct contact with consumers. But the information function is also very important for companies when it comes to ecological social problems. Partners often have extensive knowledge of how the ecosystem works and can provide companies with information to solve a business problem. 35

Another benefit for companies is the safeguarding function. In the event of damage or a scandal involving the company, the view of the company is already more positive in advance and the damage to the image of a corporate citizen is less than that of a company with little or no involvement. In this way, committed companies are seen as more trustworthy and are trusted to repair this damage and not to commit it again. Social commitment can therefore to a certain extent cushion damage to the company’s image. This point is often seen by companies as an important reason, as the company has protection in the event of a scandal. 35

These more theoretical benefits can also be applied specifically to companies. Wildner divides the benefits into the various company levels. He first explains the benefits for the business units, then the possibility of competitive advantages and finally the benefits for the company as a whole. The business areas that benefit most from CC engagement are sales (and, to a lesser extent, marketing) and human resources. Commitment in the sales area, for example, has a positive impact on sales figures. Cause-related marketing in particular leads to higher sales figures for the product. However, it is important to adapt the engagement to the company and select the right engagement. Companies can also benefit from social commitment in the area of customer acquisition. By working together with a partner, the customer can be won over by the company. Companies can also gain customers through positive media coverage. In management consulting, for example, customers can become aware of the company through positive media coverage. This is because a positive image of their new business partner also has an advantage for customers. The information function mentioned above also benefits sales. The information gained from a CC engagement can then be used further for business customers. In contrast, the advantages are clearer when it comes to personnel development. Corporate volunteering measures often have a positive impact on the team structure. By getting involved together, they grow closer together than is the case with team-building measures. Corporate volunteering measures often also offer a better alternative to further training measures. Communication and leadership skills can be learned better in real-life situations than in simulations. 3

Overall, involvement in the company’s local environment also improves location-related factors. In particular, the human resources and infrastructure of the location can be improved. Improving human resources is therefore advantageous, as these people are potential employees of this company. For example, the induction period can be reduced and qualitatively demanding positions can be better filled. At the same time, local demand conditions such as the size of the market and the development of product and process standards can be increased through the commitment. Structurally weak regions can be promoted and develop into attractive locations. Local competitive conditions can also be sustainably improved by combating corruption, for example. These points all support the last point. The establishment of related and supporting industries. By improving the location factors, related and supporting industries can be established, which can also represent an advantage for the company. Overall, it can be seen that improving the location factors creates competitive advantages that can be very important for the company. 3

From the perspective of the company as a whole, the improvement in corporate reputation is probably the most important benefit. There is disagreement in the literature as to how exactly a benefit for companies develops here. Overall, however, it can be said that corporate reputation has a positive influence on stakeholders, in line with the above-mentioned relationship management point. Several studies confirm that there is a positive correlation between the commitment of companies and their sales figures. The sympathy gained often drives consumers to buy the company’s products, as the general image of the company is a factor in the purchase intention on the one hand and customers want to reward the company’s commitment on the other. Employees are also influenced by the more positive image. This makes the company attractive on the job market and thus better able to fill its vacancies. But identification with the company and greater satisfaction also bring benefits. Investors also pay attention to a company’s image. On the one hand, they can use the investment itself to improve the company’s image, as they are investing in a “good company”, and on the other hand, sustainable companies are more successful in the long term. Suppliers and vendors are positively addressed by the above-mentioned relationship management of social commitment. Successful partnerships with non-profit organizations signal credibility and reliability. Probably the most important point for maintaining a positive image is the relationship with NGOs and the media. This is because a positive image could lead to recommendations from these groups or, in the worst case, in the event of a scandal, lead to less protest action and illumination of the problem. However, companies that present themselves as role models are scrutinized and illuminated particularly critically. The last stakeholder, the legislators, are also positively influenced by the corporate image. For example, companies with a positive image can rely on better decisions regarding permits and also on lower costs for these decisions, while remaining within the legal framework. 3

From a corporate perspective, CC engagement can lead to greater networking between the various business areas, as all areas are involved in the objectives of CC engagement. This integration can also lead to more networking in the core business, which can ultimately lead to synergy effects. Corporate volunteering can also create networks and connections throughout the company, which can have a positive impact on cooperation between departments. The information function can also be applied to the corporate portfolio in particular. Information from the various stakeholders, as well as information from the charitable projects, is of great importance for the corporate strategy. The last point is risk identification, which can derive particular benefit from the information. For example, non-profit organizations with a great deal of expertise can make companies aware of risks in the context of projects that could have an impact on the entire company. For example, projects involving IT students can identify new threats to the security of stored data. These could then be applied to the entire company. However, the most important function in risk identification is the safeguarding function, whereby companies can cushion missteps. 3

5.1.2 Organization Case

After explaining the benefits for companies in the previous chapter, this chapter looks at the benefits for society. At first glance, the benefits for non-profit organizations may be clear. The organizations receive support from companies, which they can then use for their purposes. However, the question that should be asked is not the benefit to the non-profit organizations, but whether the companies have a positive impact on solving community problems. After all, this is what the company should achieve in the true sense of corporate citizenship. 36

The first question that arises is what exactly a social problem is and how it can be solved. The question of the definition of social problems is not so easy to answer. The term has no clear definition and is even used in sociology with different opinions. According to his observations, a social problem is seen by many as a disorder or grievance in society and should, in the general opinion, be solved by politics or other institutions. Although Groenemeyer then argues for a different description, it is specifically tailored to sociology and exceeds the requirements of this subject. He then differentiates between social problems and problem situations. The difference between the two lies in public attention. Social problems have already been identified as a problem by society, whereas problem situations lack public awareness. However, it is not only social scientists who are responsible for drawing media attention to the problem situation; companies can also recognize these problems through their day-to-day business and bring them to the attention of the public. Due to their specific sectors, companies are often particularly well placed to identify problems that many others have little or no insight into. Polterauer cites the example of the mortician, who can identify the loss of a culture of mourning where many other observers have no insight. It is also important to mention that social problems change over time and in different places. For example, in many parts of the world, child labor is considered absolutely unethical, while in countries where child labor occurs, child labor is not seen as a problem, but rather the working conditions, because families are dependent on the income.

Once the social problem has been identified, the next step is to solve it. State actors are actually responsible for solving social problems. However, due to the decline of the welfare state and the increasingly complex problems, more and more civil actors are taking on this role. The problem can be solved in five different ways. By not addressing the issue, the problem is supposedly solved by the fact that attention for the issue continues to decline. However, the problem situation then continues to exist, whereby the social problem is now degraded to a problem situation due to the lack of attention. With the pseudo solution, the social problem is only solved for one group involved, but remains for the rest. Often only a small part of the problem is solved, while the real problem remains untreated. The next option is to shift the issue. In this way, social problems can be solved by shifting them to more manageable problems. This is merely a matter of interpreting and presenting the problem. The fourth form is the first form in which problems are actually solved. Here, companies solve this problem at the same time as solving another problem. Most problems are solved in this form. However, due to the lack of intention in the fourth form, only the last form (social problem solving) can be called an actual CC. This form solves the social problem conscientiously and with intention and is therefore the only form that solves the social problem for all stakeholders. The company must ensure that its intended social effects achieve a long-term improvement in the defined problem. 37,38

5.1.3 Research findings on the benefits of corporate citizenship

An empirical study has also established a concrete link between social performance and financial performance. It analyzed empirical data from 30 years. The empirical research has shown that social performance correlates positively with financial performance. The link between social performance is bidirectional and simultaneous. Corporate reputation is the most important factor for the positive link. Accordingly, this study confirms the statements that CC has a benefit for companies. 39

The final question in the 2018 CC Survey was what the companies consider to be the greatest added value for the company from the engagement. Protecting their reputation/brand dominated at 66%. This part is even more important for large companies (90%). The next three are increasing employee loyalty, location attractiveness and employer attractiveness (all 40%). This shows that companies, like the study, see corporate reputation as the most important factor. This confirms the statement that CC has a benefit for companies. 18

5.2 Criticism of corporate citizenship

CC has given the business world a model that describes the responsibility of companies. CC also offers companies an opportunity to get involved in society and to fulfill their social responsibility accordingly. Nevertheless, there is also criticism of the model.

The first criticism lies in the voluntary nature of the approach. Companies have generally recognized responsibilities towards society. Regardless of the definitions and the exact scope of responsibility, most authors agree that companies have a fundamental responsibility to society. The problem with the concept of CC and the similar concept of CSR (which many authors consider to be the same) is that companies are not obliged to fulfill their responsibilities. Furthermore, concepts such as CC and CSR even prevent companies from being legally compelled to assume their responsibility. Although voluntariness is an important component of corporate citizenship, it also stands in the way of state regulation. However, the criticism goes one step further. Companies deliberately prevent state regulation by practicing CC to the extent necessary to avoid state regulation. 40

The second point of criticism is the false understanding of a market economy that underlies corporate citizenship. According to Adam Smith’s well-known theory, the basic principle of a market economy is that the private pursuit of profit leads to prosperity for all. It is precisely through the private pursuit of profit that the invisible hand provides for the common good. However, CC’s concept of promoting contributions to the common good has the exact opposite effect. CC weakens the profit principle and ensures a less efficient market, which then also ensures less public welfare. Efficiency and the associated welfare are linked to functioning competition. However, CC tends to lead to barriers to competition, such as higher environmental and safety standards, which make market entry more difficult. In addition, the CC concept further diminishes the people’s trust in the market economy, which leads politicians, who ultimately carry out the will of the people, to even more market-restricting regulations. 40

The final point of criticism is not criticism of the model, but of the problematic implementation. Companies have to contend with a number of difficulties when it comes to implementation. Like many other terms, the concept is not clearly defined. For example, although almost all large corporations participate in the CC movement, they have difficulties in implementing it. Like academics, they also have difficulties in defining the term and determining the right approach. Due to the difficulties in implementation, CC cannot be implemented properly either.40

6 Corporate Citizenship in practice

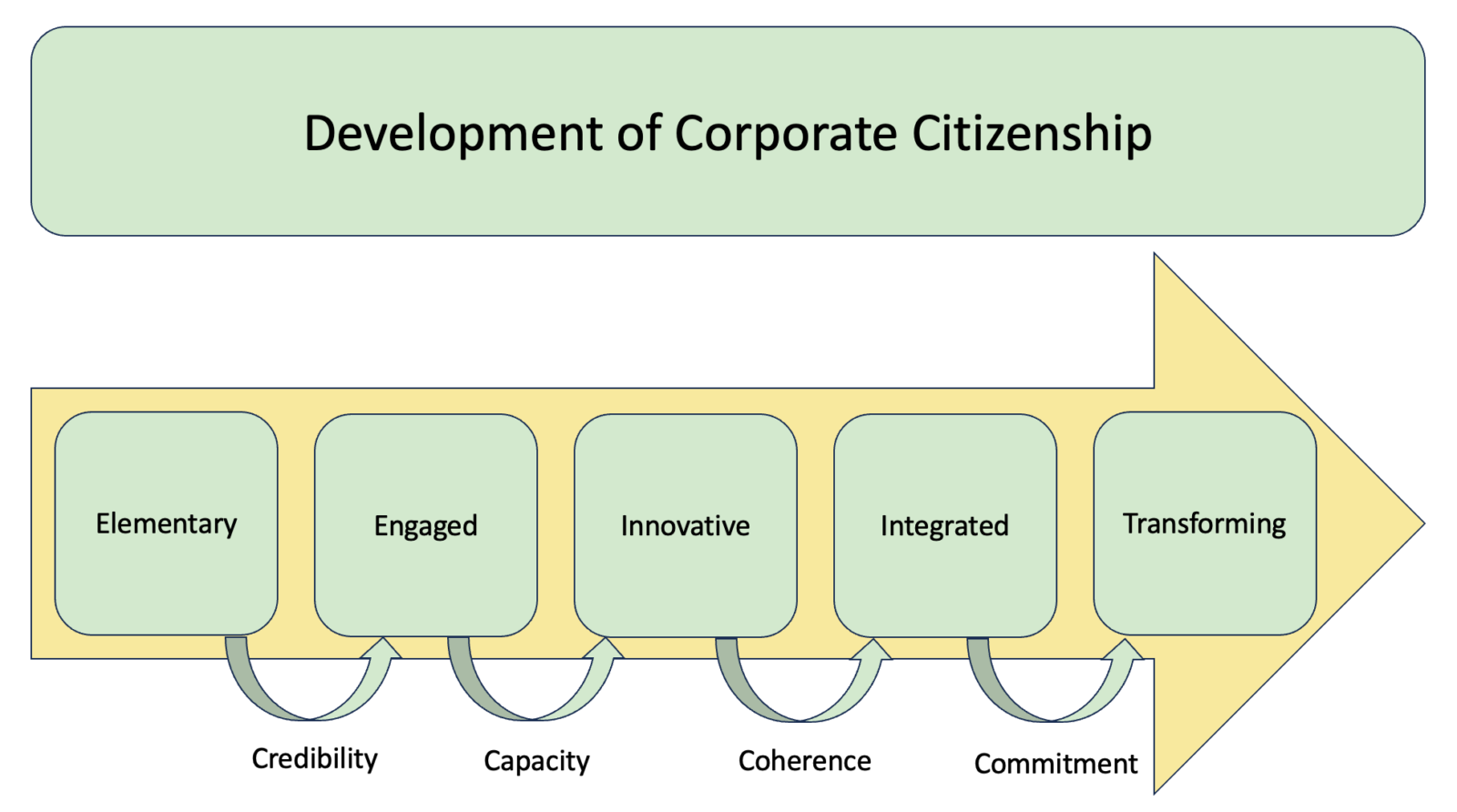

6.1 Stages of Citizenship

The Center for CC at Boston College has developed a framework to illustrate the various stages of corporate citizenship (see Figure 5). The authors (Mirvis and Googins) are well-known founders of the broad definition of corporate citizenship. The definition in their framework is as follows: a corporate citizen minimizes harm, maximizes benefits, is responsible and active to key stakeholders and supports strong financial results. In doing so, companies should strategically plan their core business and engagement according to their history, sector, size and other influencing factors. The goal of the framework is to create a categorization of corporate citizenship, delineate the different levels and outline opportunities to reach the next level.41

The basic idea behind the concept is that studies on children and also companies have recognized that there are certain activities at certain stages of development. Development as a corporate citizen is a gradual process. The ascent to a higher level is always caused by certain crises to which the company must react. The dimensions that justify the categorization into a certain level are the citizenship concept of the company, the strategic intent, the actions of the management in relation to CC, the structure of the CC engagement, how the company manages its stakeholder relationships and the transparency of the company. 41

6.1.1 Stage 1: Elementary

Small and medium-sized companies are usually represented in the first stage. The main intentions of the companies are the continued existence of the company. The good purpose of the company is jobs, earnings and taxes. This is ensured by complying with laws and company standards. Stakeholder relationships are of a one-sided nature. In this phase, the companies secure the important cornerstones of corporate citizenship. The company is profitable, complies with laws and acts ethically. However, the companies either do not have the capacity or the knowledge to become more involved. As the company grows, however, it is confronted with the fact that simply complying with laws and standards is no longer enough to be seen as a “good” company. The company usually learns of this through a crisis and experiences the risk of damage to its image. 41

6.1.2 Stage 2: Engaged

Having reached this stage, companies usually recognize the need for CC as a result of the crisis described above. The crises often involve unethical activities on the part of the company. In this phase, companies often develop a corporate policy aimed at preventing legal disputes and damage to their image. As a result, societal, environmental and social problems receive more attention within the company. Nevertheless, companies only react to the most urgent problems that cannot be avoided any longer. To do this, the companies call on the help of external experts who provide the companies with concepts. Stakeholders are also consulted at this stage. The next crisis then arises due to the insufficient capacity of employees to cover all necessary areas and react to necessary developments. This crisis leads to the company initiating an innovation phase in which programs are created, stakeholders are involved and the company becomes more transparent. One example is Shell’s plan to sink the Brent Spar oil platform in the North Sea in the mid-1990s. The plan to sink the oil platform and the huge negative criticism that followed was the crisis that propelled Shell into the second stage. Shell subsequently established a crisis management system that laid down specific social and environmental principles in order to save Shell’s image and survival. Over the next few years, they then developed concepts to support their sustainable development.41

6.1.3 Stage 3: Innovative

In this stage of development, the company expands its commitment to CC and deepens its role as a pioneer of the movement: This stage is characterized by a high level of innovation and a lot of learning. Stakeholders are more involved and experts from the various areas are consulted. Many programs are planned and implemented in this phase. These are planned, follow a certain logic and are monitored by the company. The second important feature of this phase is that companies assess and publish their social and environmental performance. However, these publications still consist purely of data that is merely prepared for the public. Countless corporate scandals have made companies increasingly transparent. The company is now also responsible along the supply chain. The crisis that then forces the company into the next stage is the lack of a strategic plan in the implementation of citizenship projects. Many companies are being implemented and evaluated, but due to the lack of a strategy, they are ineffective, uncoordinated and too broad. An example of this is Baxter International (a large healthcare company) in the early 1990s. They published their economic, environmental and social performance early on. It was also one of the first companies to publish its performance in relation to the Ceres Principles. At a very early stage, it pursued the idea that the company is not only responsible to its shareholders, but also to its stakeholders. 41

6.1.4 Stage 4: Integrated

At this stage, companies must evolve from pure project coordination to collaboration. Management sets standards and monitors the company’s performance in the engagements. At this stage, CC is introduced into every business unit. Management sets targets and monitors them. The publication of social and environmental reports and the disclosure of problems in these areas are also features. Companies are committed to full transparency, as they are not involved for business reasons, but because of their values. This often results in contradictions between the commitment and the company’s core business. The credibility of the commitment suffers as a result of these contradictions. To advance to the next level, CC must be incorporated into the company’s strategy. An example of this stage is British Petroleum (BP). The company has been one of the pioneers in trying to incorporate CC into all areas of business. They have set out social, economic and environmental sustainability goals for the company. These were then monitored by committees that were firmly anchored in the company. 41

6.1.5 Stage 5: Transforming

Even companies that are at this stage of development do not have all the characteristics of a corporate citizen but are on the right track and are setting a good example. They often have an innovative leader at the top of the company. These companies often seem to stand up for the values they represent. These values are the product of a long company history, the world’s social and environmental problems and a strong understanding of corporate citizenship. In addition, they rarely work alone in their commitments, but almost always with partners (other companies, associations or NGOs) in order to tackle problems more effectively, reach new markets and strengthen local economies. The companies use CC tools, such as cause-related marketing, and represent the values with their entire company. The aim of the companies is to open up new markets by blending CC and their core business. However, this level should not be seen as the highest level to be achieved. As companies can continue to develop and the term can take on new meanings, further levels can be added or adapted. 41

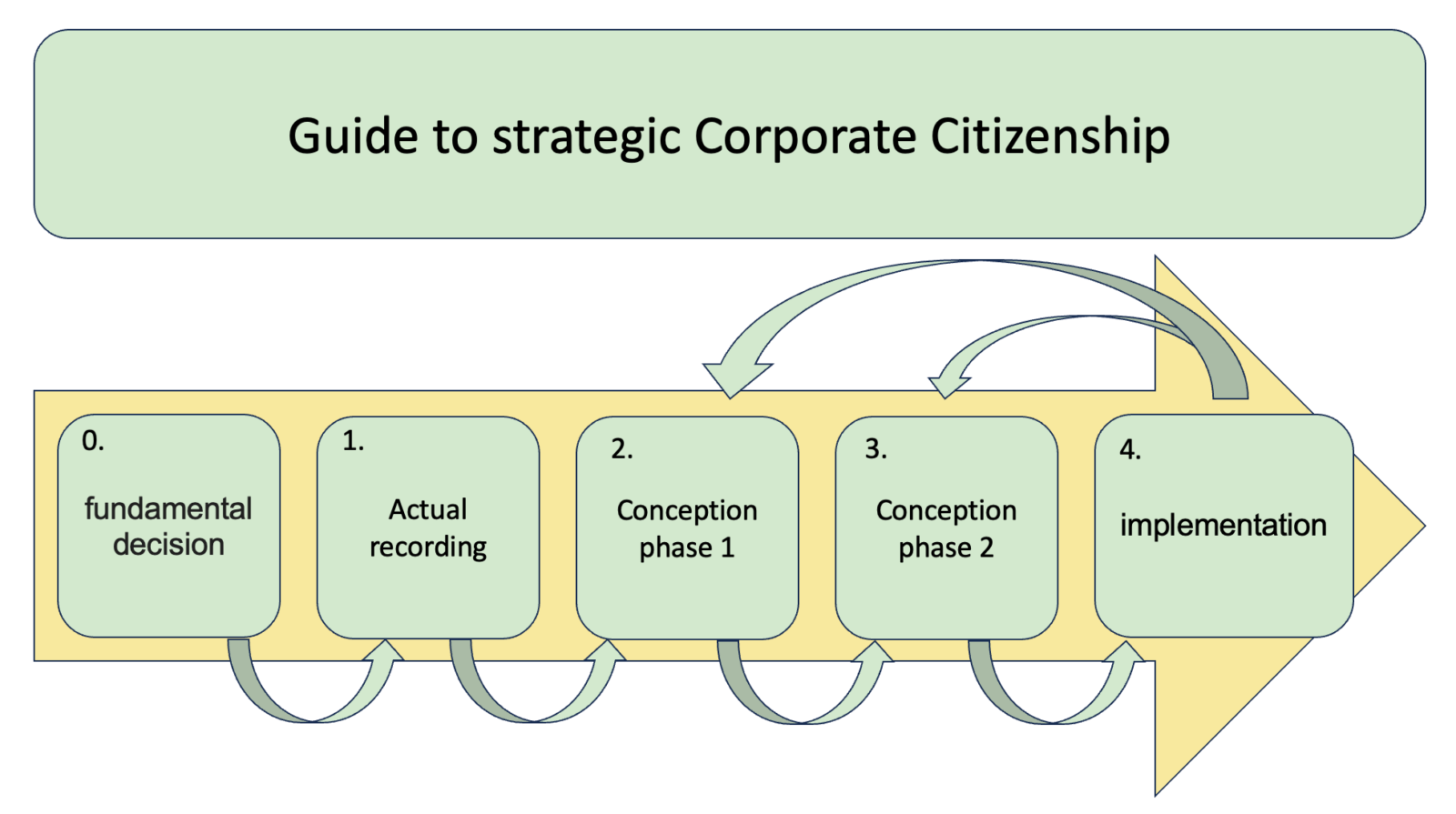

6.2 Strategic implementation

6.2.1 Strategic starting points

CC should create concrete win-win situations between companies and society. Therefore, there are basically two areas that require strategic objectives. On the one hand, there is the solving of social problems. Depending on the values, profile and skills of the company, a decision should be made in favor of one or more social problems. These problems are then sustainably solved or at least alleviated through projects. Companies should constantly analyze their projects and the problem in order to monitor the efficiency of the project and the achievement of the goals. On the other side of the win-win situation are the benefits for the company. As outlined above, companies have several indirect benefits from this commitment. When selecting projects, companies should consider the specific benefits for the company. The most important benefits are employee satisfaction, corporate image and the safeguarding function. However, in order to achieve these benefits, companies must actively pursue these goals and realize them through suitable projects.

6.2.2 Success factors

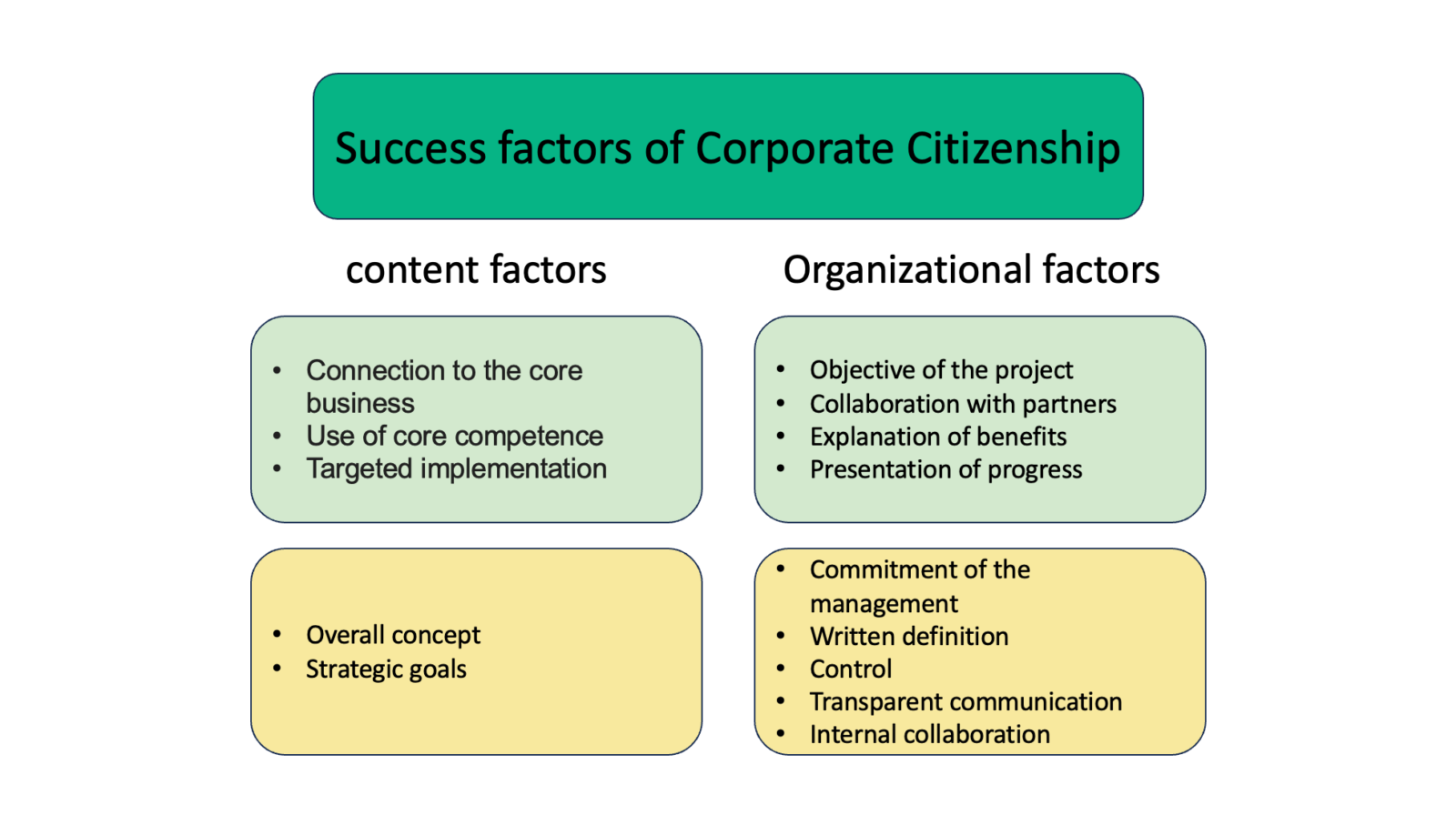

It is difficult to formulate general success factors due to the many engagement tools and areas. Nevertheless, in practice it is possible to identify certain characteristics that have led to long-term success. Habisch distinguishes between factors for overall engagement, individual projects and content-related and organizational success factors (see Figure 6)

6.2.2.1 Content factors

At the level of overall commitment, the most important factor is the bundling of projects into a coherent overall concept. By bundling projects, the commitment is focused on specific social problems. This allows social problems to be tackled more efficiently. On the other hand, the companies should also incorporate their corporate strategy goals into this concept. The resulting concept allows both the social problems to be solved most efficiently and the achievement of corporate goals to be ensured.

At the individual project level, there are more specific factors that companies should consider. The first important factor for long-term success is the link between engagement and the core business. This means that engagement must be related to the company’s activities. Projects should be within the competencies of the company and its employees. The second factor is the use of these skills. The company can further develop its competencies through new conflict situations and the engagement can have the greatest possible impact thanks to the high level of expertise and the many technical possibilities. The third factor describes the targeted implementation of the project. The appropriate CC instruments, the right area of engagement and the right partner must be selected for the project. The last point is the long-term nature of the commitment. Projects should last at least three to five years and ideally even longer.

6.2.2.2 Organizational success factors