Authors: Alex Chiarodia, Niklas Rottinghaus, Olivier Scholübbers, Tim Leon Datter, August 31, 2024

1 Definition

Education lays the foundation for individuals to navigate through an increasingly complex and demanding world.[i]Research, particularly from Western countries, demonstrates a correlation between educational participation and achievement with various positive outcomes, such as improved health, well-being, active citizenship, and employment.[ii]Further, education allows people to take the time to think critically, solve problems and make sustainable decisions which benefits them in succeeding in their careers and personal lives.1 It is not only a fundamental human right but also an essential requirement for personal and social development. From an early age education shapes the way individuals perceive the world around them, indirectly or directly influencing their values, motives and personal behaviors. Following the basics of personality development, it is influenced by two different processes – inheritance and learning.[iii] While inherited dispositions remain largely constant, learned dispositions are dependent on the environment and the respective caregivers.3 This highlights the importance of educational institutions who play a crucial role in this context,[iv] as they can not only impart knowledge but also guide and direct students in their personality development from a young age. By promoting personal growth and the application of learned knowledge and skills, education can serve as a bridge between individual goals and joint goals, particularly in terms of sustainability development.[v]

Educational Institutions are present from the early childhood through to school education, secondary schools and universities but also in further training measures offered in companies. This includes providing resources for special educational programs, development of curricula and the implementation of new teaching methods based on recent trends or technologies. It’s designed to be present and ensure continuous support in an individual’s educational journey. To better understand and categorize the various aspects of educational life, relevant studies in this field typically divide them into two main categories: Lower Education Institutions (LEIs), which includes pre-school, primary and secondary education and Higher Education Institutions (HEIs), which contains university-level education and beyond. In the context of this Wiki entry, the topic is expanded to include education in companies, referred to as Corporate Education. It can include education programs and educational institutions during vocational training, but also after it, in the form of educational seminars to expand on a theoretical field or learn new methods/technologies. These three subject areas cover the entire educational spectrum of an individual, from the earliest stages of education through to professional development. Each of these areas has different thematic requirements and implications for learners, but also for teachers and institutions, which must be considered.

1.1 Economic Importance

The importance and relevance of education have long been considered a priority.5 The significance of education is reflected in the public total expenditures in this area. In the United States, expenditures for 2020 accounted for 10.9% of total public expenditures, which is 5.1% of the GDP. Similarly, in the EU, the average is 8.8% of total public expenditures, which is 4.3% of the GDP.[vi] The majority of international investments in the education sector originate from political bodies (governments), underlining their commitment to promoting its economic importance and its status as a privilege.[vii] Education not only plays an important role for politics and society, but also plays a role in the economic growth of a country.[viii] Initial assumptions suggest that it is difficult to determine the extent and exact causes of economic growth. Nonetheless, the following studies have found an approach.

The study by Goczek et al. (2021) recognized that essential skills learned through quality education beginning with Lower Education have a positive influence on later economic growth. In this context, their analysis using PISA results indicated significant findings: the coefficient for Reading is statistically significant; the coefficient for Mathematics is also significant; and for Science, the coefficient is significant.8 The authors supported the findings with quantitative evidence of robustness to changes in the order of lags and confirmed the validity of the conclusion. This underlines the importance of investing in the educational (infra)-structure already in the early years of an individual. Another study by Kurihara, similar to Goczek et al., uses empirical data to examine the impacts of educational systems and skill development on the economic performance of countries. Kurihara finds that the educational system significantly boosts GDP per capita, indicating a strong positive effect.[ix]

The robust association between education and economic outcomes demonstrated in these studies not only advocates for increased public expenditure in education but also highlights the need for strategic educational reforms that prioritize both breadth and depth in learning and teaching.

2 Background

In recent years the trend and the need for integrating sustainability into education programs has become increasingly apparent.[x] For Example, the European Union (EU) has developed initiatives aimed at promoting sustainable development (SD) in Education. With the introduction of programs like Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) to encourage European member states to incorporate sustainability into their national education policies or Erasmus+ to directly target interested students in studying abroad[xi], initial approaches for a “modern and more sustainable Europe, able to address the digital and green transitions”13 (p. xiv) were made. However, the possibilities to integrate sustainability into educational programs across educational institutions and countries have not yet been fully utilized. Relevant studies indicate that Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) has gained significant popularity and visibility on a global scale, particularly within higher education.10 [xii] Still, the ability to fully integrate ESD into mainstream teaching and academic programs remains limited.10 Many countries see no direct benefit in promoting SD through education and feel financially and temporally restricted.[xiii] Therefore, the holistic and transnational aspect must also be considered.13

2.1 Impact of Education in Sustainability

In 2015, the United Nations (UN) introduced the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), also referred to as the Global Goals, as a worldwide initiative to eliminate poverty, safeguard the environment, and guarantee that all individuals experience freedom and harmony by 2030.[xiv] Presently, approximately 262 million children and teenagers are out of school[xv] which could result in the additional impoverishment and marginalization of 750 million people.[xvi] To address this, the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) is creating an educational environment to encourage global citizenship free from hatred and prejudice.[xvii] Its objective is to ensure that every child and citizen has access to quality education by strengthening both national and cultural ties. The educational goals are fundamentally encapsulated in Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4), which aim to ensure inclusive and equitable education and to promote lifelong learning opportunities for all in all educational systems by 2030.[xviii] The international community supports these efforts through partnerships, advisory services, institutional capacity building, monitoring, and advocacy.[xix] The goals were developed through an extensive consultation process led by member states, with active participation from civil society, educators, unions, intergovernmental and regional organizations, the private sector as businesses, research institutions, and foundations.[xx] Additionally, the Higher Education Sustainability Initiative (HESI) was launched in collaboration with various UN institutions, to encourage higher education institutions to integrate sustainable development into their teaching and research.[xxi]

In the context of reviewing the education sector the wiki considers SDGs (connected with SD and ESD) as products of the sector with the most critical impact, since all efforts in the area of education are attributable to the achievement of the Global Goals.

In the whole picture, sustainability is a comprehensive concept that includes environmental, social, and economic actions and outcomes.[xxiii] To meet SDGs, it is highly critical to embed ESD within education systems and curricula. These days countries like the United States, Spain or United Kingdom not only successfully anchored ESD into their curricula but have also developed various benchmarks to evaluate the impact of implementing such programs.[xxiv]

LEIs play a crucial role in shaping students’ perceptions of sustainability. A study published in 2022, which investigated the effectiveness of ESD among 760 students, indicates that ESD in secondary education significantly affects the development of students’ action competence, particularly regarding their knowledge of action possibilities and their willingness to act. Additionally, teacher development was found to play an important role too, mainly in promoting a holistic approach to ESD teaching. According to the study, the approach, which aims for long-term change, demonstrates that developing these competences takes time, and the implementation of ESD in formal education can be a lengthy process.[xxv]

Therefore, HEIs, as key agents dedicated to education and research, play a critical role in preparing graduates who are committed to SD. At the same time, they must set an example for their students, staff, and society as a whole.[xxvi]

College or university education is typically the final stage of formal education before individuals enter the workforce, where they go on to have significant impact as professionals.[xxvii] Aside from that, companies are increasingly expecting HEIs to produce graduates who can effectively apply sustainability and critical/systems thinking to complex everyday challenges.[xxviii] For instance, business students one day become managers and shapers of global society. Hence, sustainability is of importance for addressing current (and yet to emerge) global topics.[xxix] Furthermore, corporate sustainability studies stipulate that, for instance, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) can foster employees’ action competence for sustainability through workshop training[xxx], ultimately demonstrating that sustainability is relevant at all educational stages.

2.1.1 Environmental Impact

Educational institutions constitute one of the largest components of the public sector and play an important role in terms of carbon emissions.[xxxi] For example, the education sector in China consumes 40% of the total energy within the public sector.[xxxii] Nonetheless, HEIs are striving for improvement in terms of carbon emissions: A study found that there is a correlation between per capita footprint of universities and national per capita footprint. On average, emissions from universities correspond to around 23% of national per capita emissions which means that universities’ per capita emissions are often lower than national averages.[xxxiii]

Colleges and universities across the United States, have established a range of innovative research programs to enable students to explore diverse approaches to environmental preservation and sustainability.[xxxiv] For instance, Harvard University has advanced two interconnected environmental initiatives that are strengthening the national commitment to addressing both the immediate and long-term effects of climate change. These initiatives, known as Fossil Fuel Neutral by 2026 and Fossil Fuel Free by 2050, focus on building resilience against the impacts of carbon emissions resulting from energy production. Fossil Fuel Neutral by 2026 is a short-term ecological strategy aimed at offsetting fossil fuel consumption and neutralizing residual greenhouse gas emissions. This initiative involves collaboration with researchers and industry leaders on investment projects that focus on green energy production from renewable sources. Fossil Fuel Free by 2050 is a complementary initiative that extends Harvard’s commitment by ensuring all campus facilities transition to clean, efficient, and renewable energy sources. This initiative aims to be cost-effective while safeguarding environmental integrity for the coming decades.[xxxv] There is an indirect environmental impact as well. A panel data analysis for 179 countries indicates that education has a significant impact on CO₂ emissions. This is because higher education raises awareness of environmental issues and motivates people to use environmentally friendly devices and technologies. In addition, higher education encourages the development of innovative, efficient and environmentally friendly technologies that help control pollutant emissions.[xxxvi] Promoting sustainability competencies in schools enables students to develop key qualifications that empower them to understand complex issues related to sustainability and make informed, responsible decisions.[xxxvii] These competencies include cognitive skills, critical and systemic thinking, as well as ethical values and attitudes that help students reflect on the impact of their actions on the environment. These educational approaches often lead to sustainable behavioral changes, such as waste reduction, more conscious consumption habits, and increased engagement in environmental within the school context and in daily life.[xxxviii]

2.1.2 Social Impact

SDG 4 includes seven key objectives aimed at addressing gender disparities in education, reducing dropout rates across primary, secondary, and higher education, and expanding opportunities for disadvantaged groups such as scheduled castes, indigenous peoples, and individuals with disabilities (refer to Fig. 1). Furthermore, it features three sub-objectives designed to help achieve these seven primary targets (4.a-c).[xxxix]

The well-being and quality of life of students are crucial for the sustainability of higher education, a fact underscored by the COVID-19 pandemic, which highlighted the need for supporting students’ emotional health, particularly in online learning environments. Institutions that prioritize psychological well-being enhance academic success and contribute to the persistence of students toward graduation.[xl] Effective sustainability education often requires pedagogical approaches that engage students actively and relate environmental knowledge to social justice and community involvement.[xli]Research has shown that academic coursework, such as taking a course in environmental studies, plays a significant role in shaping students’ behaviors, often leading to more responsible actions. While students who take a sustainability-related course in the natural sciences and business/economics/policy tend to think about this term in more environmentally centric ways, those who take courses in the social sciences and integrated courses directly related to sustainability tend to broaden their conceptualizations of this term to include notions of democratic participation, community, systemic change and innovation.[xlii] Schools that adopt a holistic approach to integrating sustainability create an educational culture that promotes sustainable thinking and action across all areas—from teaching to school administration and infrastructure to community collaboration.[xliii]

2.1.3 Economic Impact

Achieving quality education is essential for developing a skilled workforce that can drive economic growth, reduce inequality, and ensure inclusive and sustainable employment opportunities.[xliv] Hence, there is a link between economic growth and SDG4.

Economic Growth is related to SDGs 8 which aim to promote sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all. The goal seeks to achieve at least a 7% annual growth in the economies of less developed countries, increase economic productivity, and enhance the participation of women in the economic system. By focusing on these targets, SDG 8 strives to create a more equitable and prosperous global economy where everyone has the opportunity to benefit from economic progress.[xlv]

As we have already covered in the beginning sustainability is a significant driver for economy. Empirical studies show that education in sustainability plays an important role in the long term by increasing labor productivity and strengthening human capital. Higher educational standards lead to a more qualified workforce that is more productive and innovative, which in turn promotes economic development.36 Further findings of a study demonstrate that CEOs with an MBA degree have an influence in the association between corporate performance and corporate social responsibility (CSR) which highlights the importance of quality education.[xlvi]

Though, empirical evidence also highlights that economic and financial ideologies and considerations often influence wider issues of sustainability.[xlvii] This is not surprising given the fact that internal structures and cultures of business schools shape and influence the way their staff and students think and act.[xlviii]

In order to achieve the SDGs, it is therefore important that ESD measures are applied across the board, right down to the business schools, so as not to stop or sabotage sustainability development.

2.2 Sustainability Measurements

To create policies aimed at achieving sustainable development, it is essential to have robust measurement frameworks and indicators to monitor progress against major development challenges.[xlix] [l] Measuring sustainability performance helps stakeholders recognize critical sustainability issues and gaps and track improvements over time. This capability also supports policymakers in designing and planning interventions that align with sustainability goals while minimizing trade-offs between different sustainability dimensions. Yet, measuring sustainability performance is far from straightforward, as it involves significant conceptual and methodological challenges. Properly understanding these challenges can help researchers, practitioners, and the general public evaluate the efforts made so far and identify areas for future work. Without this context, sustainability and its measurement risk becoming overly focused on technical and scientific aspects, potentially lacking acceptance among wider societal groups.[li]

Despite the generally high level of complexity mentioned in the previous chapter, the following paragraph will focus on measurement methods on sustainability in educational systems. It is important to highlight the gap between the current progress toward SDGs and the desired future state which in turn identifies priority issues to be addressed at national, regional, and global levels.39

Another approach is the Sulitest. It was created as a concrete implementation of the HESI, a significant voluntary effort launched during the Rio+20 Conference on Sustainable Development. This initiative brings together over 300 HEIs that recognize their responsibility in promoting a sustainable future, commit to sharing sustainable practices, and emphasize the importance of assessing and reporting on these efforts. The primary goal of the Sulitest is to meet this need by providing a tool for HEIs to evaluate whether they are producing graduates who are literate in sustainability. It consists of a “Core International Module” with 30 questions covering globally relevant topics, and a Specialized Local Module with 20 questions addressing specific local contexts. The questions are randomly selected from a question bank and cover various areas of sustainability.[lii]

Sustainability Measurement approaches in Corporate Education are important to monitor whether companies are able to comply with SDGs. One approach is called SDG Mapping/SDG Compass which links organization’s sustainability conducts with SDGs. Utilizing the SDG Compass, it gives instructions to align organizations strategy with: (1) Understanding SDGs; (2) Defining Priorities; (3) Setting Goals; (4) Integrating Sustainability and (5) Reporting and Communicating.[liii] Another possibility is using Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA). DEA can be used to measure the efficiency of sustainability training by comparing the inputs (such as training time and costs) with the achieved outputs (such as improved sustainability practices and reduced resource consumption). This method allows companies to assess the relative efficiency of different training programs and identify best practice.[liv]

3 Sustainability strategies and measures in education

In this chapter, we explain the specific sector-related technologies, processes, measures and tools that can be used to improve the sector’s sustainability performance. With the introduction of three defined subtopics—Higher Education, Lower Education, and Corporate Education—the sectors that also serve as structural reference points in this section have been established. In addition, the advantages and disadvantages of alternative models and best practices are presented using examples from universities and companies.

3.1 Sustainability tools, measures and strategies

For the introduction of measures and strategies to enhance the presence and performance of sustainability in educational institutions the use of tools is crucial.[lv] They can influence various domains, including curricula improvements, research, operations, improving sustainable thinking and knowledge transfer to companies that directly or indirectly benefit from these measures. Through measures in the areas shown as examples, a more sustainable mindset and practices can be effectively created, starting with educational institutions and students and eventually extending to companies that follow these trends, as new generations demand this change. A difficult task for modern companies, as they are noticing a shift from a short-term profit orientation to a holistic view that combines economic, social and environmental factors.[lvi]It is important for corporations to understand that integrating sustainability is a company-wide necessity and practical experiences of sustainability initiatives increase the interest in and commitment to sustainability for employees.[lvii] The following tools are primarily utilized and adapted by companies and institutions, making them particularly relevant for this wiki entry.

3.1.1 Sustainability Reporting

One process to meet the changing needs is by offering organizations the possibility to transparently communicate their values, actions and performance towards sustainable development, also known as sustainability reporting.[lviii]Sustainability reporting (SR) can be defined as “the practice of measuring, disclosing and being accountable to internal and external stakeholders for organisational performance towards the goal of sustainable development”(p.5).[lix] As early as the 2010s, organizations were increasingly integrating SR into their management practices, which include strategic planning, performance measurement and risk management.[lx] Today, SR has a much broader meaning and is reflected in all areas of a company and can have an environmental, social and economic impact.59 It can be seen as the Strategy or process for integrating Sustainability in the long term. This means sustainability reporting (SR), in addition to its role as a communication and stakeholder engagement instrument, finds significance in all aspects of the company – including corporate education. For example, the car manufacturer Mercedes Benz uses the annual SR-Report to communicate its environmental and strategic projects but also shows Its social efforts for the workers. This includes Training and further qualification where Sustainability, Integrity and diversity serves as the foundation.[lxi] Other Companies show the same interest in supporting and developing sustainability in education programs, especially in innovations that fit their industry and products such as digitalization and electrification for car manufacturers 83 61 and Programs such as responsible resource management for retail companies.[lxii] Therefore, SRs can be a way to not only track and communicate but also improve sustainability in companies.

3.1.2 University environmental management system (UEMS)

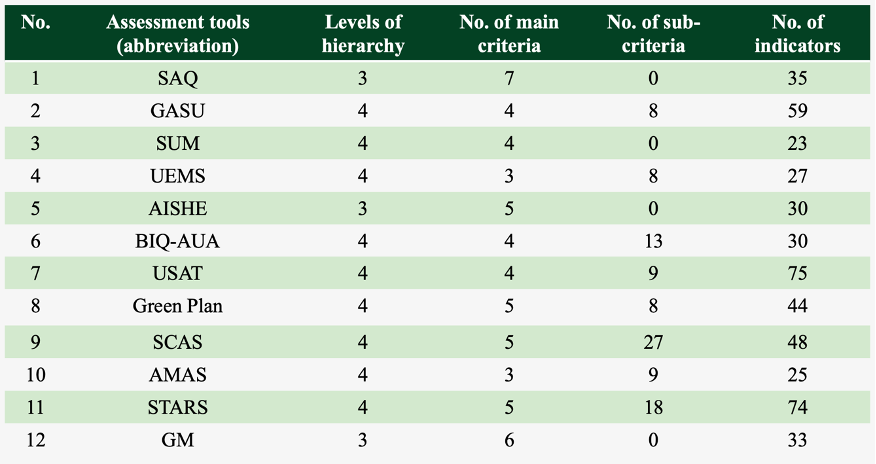

In addition to the use of sustainability reporting in the corporate environment, SRs can also be found in higher education institutions (HEIs).[lxiii] In this case, the tool is used to specifically address, promote, and communicate sustainability in teaching and the educational environment. Areas such as economic performance, environmental resources, social and educational research act as subcategories of sustainability to be implemented in various aspects of teaching and learning programmes within the institution’s perimeters.63 Furthermore, HEIs can demonstrate their commitment and better integrate sustainability into their systems by developing declarations, charters and initiatives (DCIs) to provide guidelines or frameworks for the Institution.56 One tool is the university environmental management system (UEMS) which is a framework that can be used in Higher and Lower educational Institutions. It usually consists of three strategies: public participation, social responsibility and promoting sustainability through education and research. Each strategy has sub-categories and indicators as shown in Figure 2. The purpose of this tool is to integrate a sustainability guide in a systematic way to ensure everyone directly and indirectly involved in the process is aware of the range of initiatives and actions that can be taken.[lxiv]

The Cambridge University can serve as a practical example of the Environmental Management System (EMS). They are working to get accredited to the ISO 14001:2015 (international environmental management standard) and promote environmental awareness across the staff members and everyone associated with the Cambridge University.[lxv] The EMS is part of their sustainability Report. This implies that with the help of the SR tool, not only can defined sustainability KPIs be communicated, but initiatives and frameworks can also be initiated. Consequently, SRs serve a dual function and function as drivers of sustainability in education within corporations and organizations, as well as in educational institutions.

3.1.3 Problem-Based Learning (PBL)

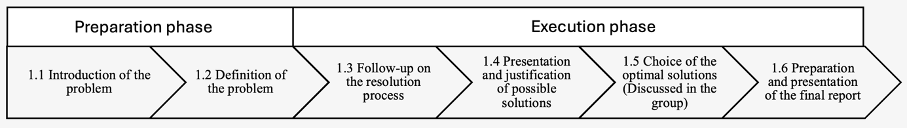

Another tool is the Problem-Based Learning (PBL) which involves students in learning collaboratively under a tutor’s supervision to solve real problems related to sustainability, thereby developing critical analysis and self-directed learning skills which focuses on sustainability and the self-learned improvement of it.[lxvi] The Tool follows two phases: the preparation phase and the execution phase, which are structured to optimize the learning process (see Fig. 4). In the preparation phase, students are introduced to a specific sustainability issue, guided by their tutor to understand the context and the underlying challenges. In the execution phase, students actively engage in gathering information, analyzing data and applying their knowledge to solve the problem. This involves collaborative efforts within their group and potentially with external stakeholders, such as local businesses or community organizations. Due to generic structure and low resources needed, this tool can be an option for LEIs, HEIs and Corporate Education, if implemented correctly.

3.2 Technology Enhanced Learning (TEL) to improve sustainable measures

In addition to specific tools to establish sustainability in HEIs, LEIs and corporate education, there are technologies to support and improve the process. Especially in the context of universities, international research on learning-technologies has been presented in relevant Journals and books.[lxvii] The term Technology Enhanced Learning (TEL) has been used in this context and functions as the term for application of information and communication technologies (ICT) for teaching and learning.[lxviii] TEL can transform both education and educational institutions.[lxix] In recent years, essential progress has been made, largely due to the internet, in simplifying the use of technology in education. Newer generations, familiar with technologies and the widespread availability of the Internet, have driven this process. This shift from stationary, inflexible content to flexible and accessible digital content allows to respond faster and more specifically to the demands of today’s educational needs. As a result, learning becomes more dynamic and modular so that it can be used immediately across different applications and websites. The integration of sustainability is also made possible and strengthened by technological changes in education. For example, the use of paper embodies the possibilities that technologies can create without expensive financial or human resources. It shows by how much new technologies can improve sustainability in education.

3.2.1 Use of Technology to reduce paper consumption in education

Paper is used by people, institutions and organizations as the main tool for numerous social, communicative, promotional, financial and educational purposes.[lxx] As a result, in the past decades, global paper consumption has surged up to 414 million metric tons. That’s an increase of 538 percent since 1961.[lxxi] To decrease paper consumption, many higher education institutions are implementing strategies and frameworks as measures. These include the use of digital libraries. This method is one of the most significant steps toward sustainable development. This method reduces the paper usage by a significant number and increase the availability of journals making them easily affordable by everybody.[lxxii] Another method to reduce the paper usage in education institutions is the Implementation of electronic tablets as a mode of examination. The step to computer-based examination can save a significant number of paper and so do a vital step toward sustainable development and environment friendliness. This measure can also improve the appropriate assessment of examination for the faculty.72

3.2.2 ICTs to achieve a Paperless Office

The paperless approach, as a motivator to save costs through the use of technology, is also a topic in companies and corporate education. Companies invest over $120 billion each year on printed forms, the majority of which are outdated within three months.[lxxiii] With the adaption to a paperless approach by promoting the use of new technologies, they can reduce the costs by around 50 percent.[lxxiv] One Method is the Paperless Office, which is a tool to use information technologies to improve the quality and accessibility of services by also decreasing the costs and protecting the environment.70 Paperless Offices act as a framework for the use information and communications technology (ICTs) through digital media platforms and devices. For example, phones, tablets and computers can be used to transfer information from one part of the office to another or even to employees at home. Paperless office does not directly mean no more paper, just less.70 But the possibilities of paper-based to web-based processing of documents or learning materials can reduce administrative costs by around 50 percent.74 In addition, electronic learning tools are more effective in formal learning situations[lxxv] and grant the possibility to provide an interactive and accessible educational content library. They also enable a more dynamic interaction between educators and students.

The implementation, management and continuous improvement of e-learning services is necessary to further increase the quality of learning.[lxxvi] Collaborative programs and capacity-building efforts significantly improve the development of learning materials, educational tools and effective practices. When combined with affordable Internet access and widespread availability of ICTs, they present an alternative to traditional education methods, particularly to enhance and simplify the possibility to integrate Sustainability measures into HEIs, LEIs and Corporate Education.

3.3 Pros and Cons of alternative tools and measures

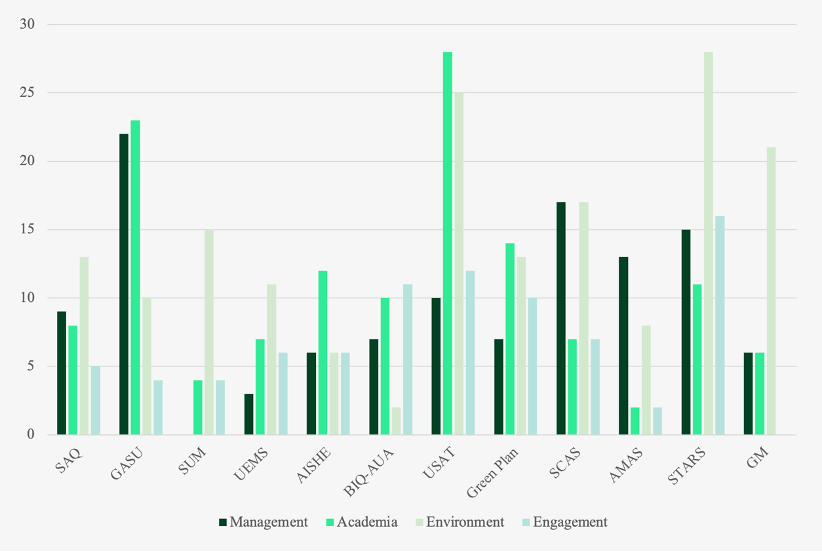

A wide range of tools have been developed to support the implementation of sustainability in educational institutions.64In addition to those discussed in the previous chapter, Table 1 presents further available instruments from the HEI field, illustrating their diversity and distinct characteristics. Each instrument’s indicators are concentrated in the following categories: Management, Academia, Environment, Engagement, and Innovation (see figure 5). In this section, we will target three alternative tools—Green Plan, Sustainable University Model (SUM), and Sustainability Tracking, Assessment, and Rating Systems (STARS). These tools were chosen due to their specific development and design for colleges and universities, with the objective of helping these institutions advance towards greater sustainability. It should be noted that the main priority of these tools is usually only the assessment and tracking of sustainability in education and less the improvement. Nevertheless, they provide a clear plan through the specific division into main categories, sub-categories and indicators which transforms them into a holistic strategy, which can be used in Institutions and Organizations. In order to avoid a one-sided view of the instruments of higher education, the two-lens model is examined in more detail at the end of this section, specifically from the perspective of corporate education.[lxxvii]

In the higher education sector, none of the three assessed instruments fully meet the criteria to be considered an ideal tool.[lxxviii] Each instrument has its own specific strengths and weaknesses. A significant issue with many of these tools is that they do not allow for meaningful comparisons with other institutions or alignment with national and international standards, for example ISO certification or standards introduced in the SDGs. Additionally, these tools often fail to explain the motivations behind their sustainability initiatives, focusing instead on what was done and how it was done.78For these tools to be effective in promoting sustainability, they need to cover all functional areas and clearly communicate their methods and results to the broader public.

3.3.1 Limitations and advantages of Green Plan, SUM and STARS

One specific limitation, for example, is that the Sustainable University Model (SUM) requires considerable time to demonstrate its effectiveness, which can slow down progress in sustainability initiatives. In addition, both STARS and the Green Plan Framework are complex, making it difficult for institutions to collect and report the necessary data.64Additionally, the costs associated with registration and participation may discourage institutions with limited budgets.[lxxix] This means that these tools are particularly effective in environments where sustainable development is already well-established, which may limit their usefulness for institutions that are still in the early stages of their sustainability efforts.[lxxx] However, this is not necessarily a disadvantage but rather a limitation. If an institution or organization has the necessary resources, these tools can still serve as valuable alternatives. Hence, a study found the STARS Model to be the most effective tool for assessing and tracking sustainability across various aspects of campus life. These alternative tools understand that sustainability is a long-term goal that requires systematic changes, such as reward systems, annual reports, and broad institutional processes.78 Additionally, they highlight the importance of including sustainability in curricula, encouraging students to apply their knowledge of environmental issues beyond the classroom, especially in their later careers.

3.3.2 Two Lenses Model (2LM)

In corporate education, with the Two Lenses Model (2LM) a unique approach is taken to increase the performance of sustainability in education. Its main purpose is to help companies identify opportunities for sustainability innovation. It combines two perspectives: the Sustainable Business Model (SBM) and Corporate Sustainability Performance (CSP).77The SBM lens focuses on how companies create, deliver and capture sustainable value, while the CSP lens assesses the efficiency and effectiveness of a company’s actions towards sustainability goals.77 The model guides companies through a structured process shown in Figure 6, to analyze their current performance, identify gaps, and find areas where they can innovate. It combines insights from both internal operations and external stakeholder needs to help companies develop practical steps to improve their sustainability. However, the complexity of the model can lead to problems during implementation, as considerable resources are required for training and the adaptation of existing systems. Despite the challenges, the 2LM offers a structured way to effectively improve sustainability practices. Although Corporate Education is not specially targeted, this tool can serve as an educational tool to develop the skills and mindset needed to integrate sustainability into business practices, making it relevant in the context of corporate education programs or leadership programs that focus on sustainable business strategies and innovation.

Due to the disadvantages discussed, the alternative methods presented do not currently have the ability to serve as an ideal tool for every institution. Now the question arises as to which (ideal) tools are used in practice.

3.3 Best practices in education to implement sustainability

Currently, the presented tools, strategies, and measures are broadly formulated and do not directly apply to specific educational institutions or organizations. With the introduction of best practices, examples of work can be presented that are partially based on the specific tools mentioned. Below the wiki describes Competency framework for Spanish Universities, EMS and ISO 14001:2015 in HEIs as best practices.

3.3.1 Best practices in HEIs

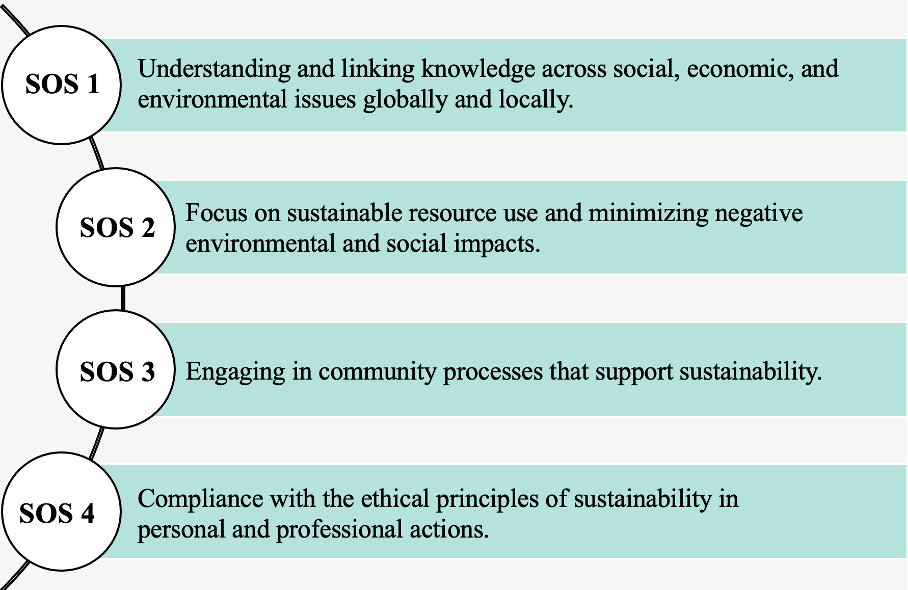

Competency framework for Spanish Universities

Particularly through the Bologna Process, which focuses on improvements in HEIs, Spanish universities have been provided a framework to integrate sustainability into their curricula.66 Essential competencies identified include critically context alizing knowledge across socio-economic and environmental issues, sustainably managing resources, engaging in community sustainability processes and applying ethical sustainability principles.66

EMS and ISO 14001:2015 in HEIs

The University of Cambridge is currently in the process of implementing an EMS according to the ISO 14001:2015 standards. The university has already implemented measures, known as EMS Scope, that lay the foundation for future environmental certification. It specifically targets a holistic approach, which includes an analysis of the environmental impacts, target, risks and opportunities, stakeholders and policies.[lxxxi]

The University of Liverpool is already further along in the process of EMS and has been accredited to ISO14001 since 2017 demonstrating its commitment to reducing negative environmental impacts as part of its wider business and institutional strategy.[lxxxii] To maintain certification, the University follows an external audit cycle (see Figure 7).

3.3.2 Best practices of tools and strategies in Corporate Education

The BMW Group increased its investment in further education and training to €469 million, up by €50 million from the previous year, showing the long-term commitment to using education as a tool for sustainable social development under the slogan: “We support young leaders committed to a fair, peaceful and sustainable future”.[lxxxiii] One initiative is BRIDGE (Educating young people for tomorrow) which supports educational projects around the world. In collaboration with UNICEF since late 2023, the focus is on providing STEM education in areas with BMW facilities, including South Africa, Brazil, Thailand, Mexico, and India. This effort aims to reach 10 million children and young people annually, equipping them with sustainable skills necessary for the future workforce of the BMW Group.[lxxxiv]

The strategies and measures have shown that there are specific tools, processes and technologies that make the use and improvement of sustainability in education plannable but are not universally applicable to all areas such as LEIs, HEIs and corporate education. Accordingly, best practices provide an exemplary context for how these strategies and measures can be effectively implemented and maintained.

4 Drivers and barriers

4.1 Factors influencing the integration of sustainability in the education system

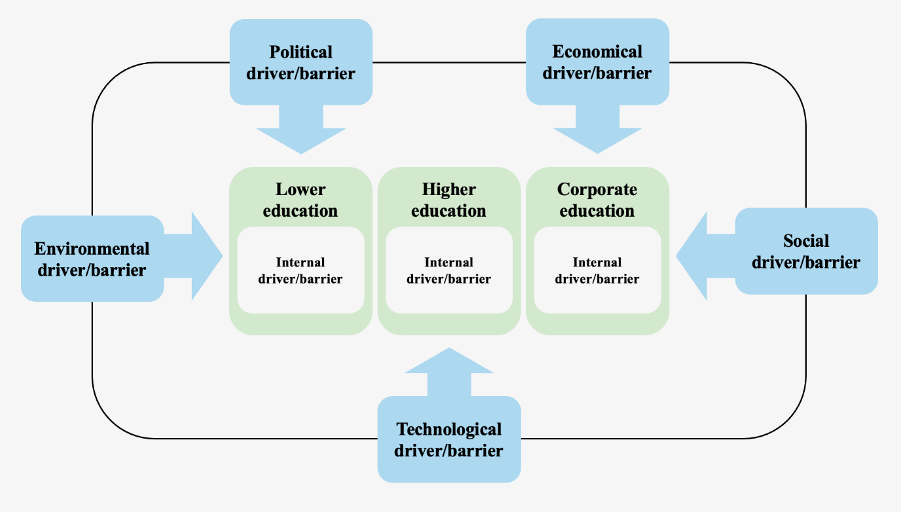

The integration of sustainability in educational institutions is influenced by a variety of factors that can be either promoting or hindering. In the following analysis, these factors are divided into two categories: the promoting factors, which are referred to as drivers, and the hindering factors, which are regarded as barriers. In order to examine these systematically, a model is used that distinguishes between an external perspective (external factors) and an internal perspective (internal factors).[lxxxv]

The external perspective comprises the systematic analysis of the macro environment in order to identify opportunities and risks that can influence the integration of sustainability into education.85 The macro environment includes all general and global influencing factors that affect both the industry and the behavior of relevant stakeholders.[lxxxvi] These external factors are crucial as they can either directly or indirectly promote or hinder sustainable change in the education sector.[lxxxvii] Section 4.2 is dedicated to these external drivers and divides the influencing factors into five categories: political, economic, technological, social and ecological.86 This differentiation enables a targeted assessment of the relevant framework conditions.

The internal perspective focuses on the analysis of internal drivers and barriers that result from the strengths and weaknesses of individual organizations and can influence the integration of sustainability.85 Section 4.3 provides a general theoretical analysis of these internal factors, highlighting typical strengths and weaknesses to create a comprehensive understanding of internal dynamics. Section 4.3 concludes by relating these internal factors to external factors in order to identify possible interactions.

In order to better understand the interplay of these factors, two current external barriers are outlined below, as a detailed analysis of external barriers is deliberately neglected in the further course.

One major barrier is the availability of resources: an insufficiently qualified labor market that does not provide enough specialists with the necessary knowledge in the field of sustainability hinders both the recruitment of experts and the training of future specialists.[lxxxviii] [lxxxix] Social factors can also have an inhibiting effect: despite an increasing awareness of and demand for sustainability, actual involvement in projects or initiatives often remains insufficient, which also slows down integration.[xc]

4.2 Environmental analysis of external drivers for sustainability in education

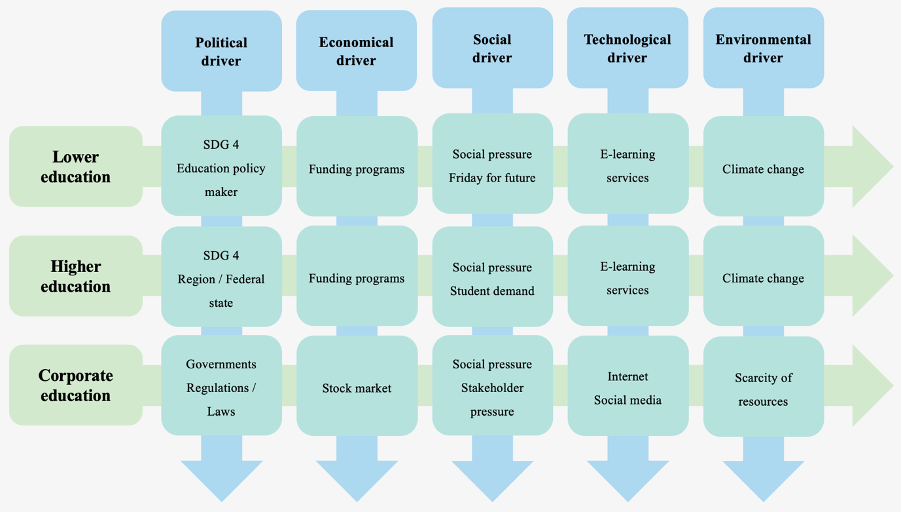

Section 4.1 explained that the categorization of external drivers is based on a comprehensive environmental analysis, considering different types of education – lower, higher and corporate education. However, as illustrated in Figure 9, there are often only minor differences in the external drivers between lower and higher education, which simplifies the analysis.

Let’s start with the political drivers, which are strongly influenced by political structures and legal frameworks.86 A significant common political driver in lower and higher education is SDG 4, described in detail in Chapter 2.1.[xci] [xcii]In lower education, however, it is emphasized that it is not only the existence of such goals that is important, but also their implementation by the actors in the education system.91 In higher education, regional and federal cooperation with public universities also plays a key role as a driving force.[xciii] In this context, local policies with a stronger focus on sustainability also influence the orientation of public educational institutions. In corporate education, on the other hand, state regulations are of central importance. A current political driver is the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), which requires companies to disclose sustainability reports.[xciv] This requirement calls for specialized knowledge in the field of sustainability and therefore leads to an increased need for training and further education measures in companies.[xcv]

Economic drivers are another external influencing factor. These include general economic developments.86 One example of this is funding that supports educational institutions in lower and higher education, such as the “Bildungssträger” funding program of the state of Lower Saxony (Germany), which provides grants for climate protection projects.[xcvi]For companies, the stock market and the associated company values can be relevant as an economic driver. Increasing demand for ESG shares can promote the integration of sustainability into corporate processes and thus increase the need for corresponding further training.[xcvii]

Social drivers are shaped by the interests and pressure of various stakeholder groups and by social developments.86Stakeholder pressure can be observed in different forms in all areas of education. In lower education, movements such as “Fridays for Future” exert considerable pressure on schools to integrate sustainability topics more strongly into the curriculum[xcviii]. In higher education, this pressure is expressed, for example, by students demanding a more intensive examination of sustainability issues in the curricula.[xcix] In corporate education, pressure comes partly from customers demanding sustainable practices, which encourages companies to take targeted training measures to integrate sustainability into their strategies.[c]

The technological drivers include both existing and new technologies as well as the development of a suitable technological infrastructure.86 Chapter 3.1 has already shown how technologies, such as e-learning services, can support the integration of sustainability in lower and higher education institutions. In corporate education, the internet and social media are helping to raise awareness of sustainability and exert pressure on companies.

Environmental drivers result from ecological aspects and climate factors.86 In both lower and higher education, climate change is a key external driver that drives awareness and the integration of sustainability into educational programs.91 [ci]In corporate education, on the other hand, drivers such as resource scarcity play a significant role, as they promote research into resource-conserving technologies and thus the necessary training of specialists for resource-conserving processes.[cii]

4.3 Factors influencing sustainable development in education: Inside view

After analyzing the external drivers and barriers – i.e. the opportunities and risks – in the external perspective, the focus now turns to the internal perspective. This analysis includes the internal drivers and barriers, which represent the strengths and weaknesses of educational institutions. Finally, a discussion will clarify the connections between these internal and external factors.

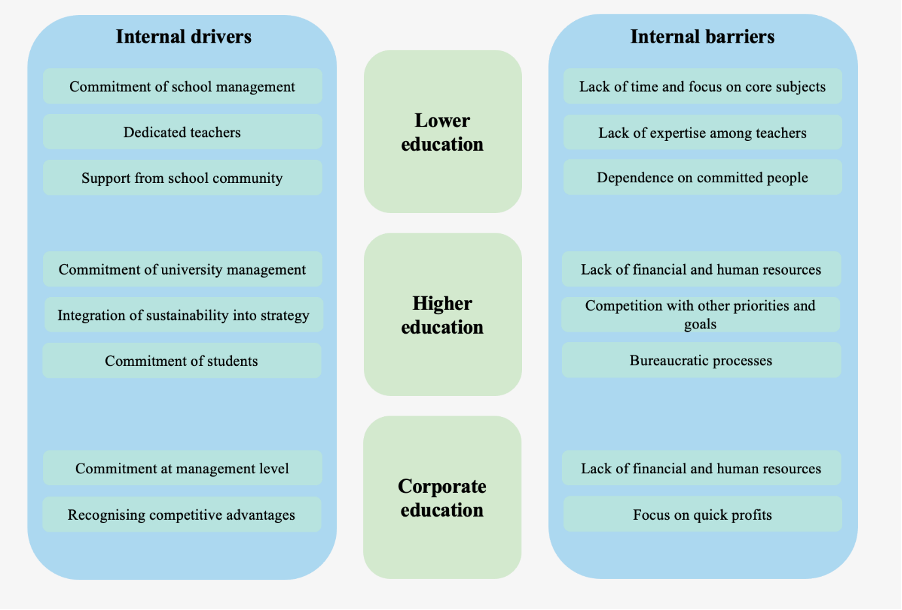

Looking at Figure 10, the internal drivers and barriers are largely similar in the different education categories – lower, higher and corporate education. Sustainability-conscious leadership, whether by school leaders, university leaders or corporate leaders, plays an important role in the successful integration of sustainability in all education sectors.[ciii] [civ][cv] Internal stakeholders are also of crucial importance: teachers and learners (pupils, students) contribute to implementation through their commitment and demands for further training and a stronger anchoring of sustainability in the curricula.103 [cvi] In higher education, a clear, strategic focus promotes integration.[cvii] In corporate education, the implementation of sustainability measures is strengthened if it can be seen as a competitive advantage.105 However, it is important to note that these drivers can also become barriers under unfavorable circumstances: As mentioned, a leader can promote sustainability, but they can also hinder it if they are a leader with weak leadership.104 [cviii]

Barriers often manifest themselves in the form of deficits – be it in terms of expertise, specialists or resources. All education sectors can be affected by a lack of qualified staff.95 [cix] [cx], which is exacerbated by the shortage of specialists mentioned in 4.1. In lower education, for example, this leads to dependencies on specialized professionals who are difficult to replace and whose emigration must be avoided.109 Another critical aspect is the lack of time, which makes both the further training of staff and the comprehensive integration of sustainability more difficult.109 [cxi] In higher education, the prioritization of other topics also acts as a barrier, as sustainability is considered less urgent compared to short-term developments.111 In corporate education, this aspect is reinforced by the focus on short-term success, especially under highly competitive pressure.[cxii] In addition, rigid and bureaucratic structures in higher and corporate education also represent a hurdle that makes the implementation of sustainability measures more difficult.106 When considering the hindering factors, it should also be borne in mind that these can act as both drivers and barriers.

In summary, it can be said that the integration of sustainability in the education sector depends heavily on the interplay of internal and external influencing factors. External drivers such as political guidelines, social pressure and technological developments create important incentives, while internal and external barriers such as a lack of specialists, time constraints, lack of commitment and bureaucratic structures can make implementation more difficult. As schools and universities differ only slightly in their specific challenges, there are common hurdles. Companies play a special role in this context but share some of the same interests. In order to achieve a comprehensive integration of sustainability into education, overarching cooperation is required that goes beyond individual educational institutions. If sustainability is anchored at an early educational age, awareness and interest in this topic can increase at later educational levels. To do this, however, schools need the necessary resources, especially qualified specialists who are trained at universities or come from there to train existing staff in schools. Companies can play a supporting role here, as they can use their economic strength to financially support educational institutions and thus create a sustainable basis for the labor market, from which they themselves also benefit. The success of sustainability integration therefore requires a strategic realignment and adaptation of internal structures in order to make the most of external opportunities in the long term.

In the following section 4.4, best practice examples are presented to show how educational institutions and companies can successfully integrate sustainability despite these challenges.

4.4 Best practices for overcoming barriers

Educational institutions today face the challenging task of permanently anchoring sustainable practices in their system and overcoming both internal and external barriers in the process. This challenge requires not only strategic planning, but also a deep understanding of the actors involved and the specific institutional dynamics. Numerous studies and case analyses show that certain approaches are particularly effective in achieving these goals and promoting sustainable development in educational institutions.

A key success factor is the role of teachers, whose motivation is crucial for school success. Demotivated teachers can significantly hinder progress. Therefore, school leaders should implement strategies that focus on empathetic leadership, transparency, fairness and fostering a supportive environment. Such measures not only increase teacher satisfaction and engagement, but also contribute significantly to the successful implementation of initiatives such as sustainability training.103

In universities, the active participation of students plays a decisive role in the implementation of sustainable initiatives. Student networks and committees that work closely with university management promote both engagement and knowledge transfer. There is a particular focus on the ongoing involvement of new students, which needs to be supported by regular training and clear communication structures.[cxiii]

Another proven model is the integrative embedding of sustainability topics into the curriculum, as is successfully practiced in Manitoba schools, for example. Instead of offering isolated courses on sustainability, relevant content is integrated into existing subjects such as science or social studies. This interdisciplinary approach promotes an understanding of the complexity of sustainable developments and enables the content to be taught in a practical way that is relevant to everyday life. Pupils are thus specifically prepared for the challenges of a sustainable future by learning to view the topic of sustainability from different perspectives and apply it in different contexts.[cxiv]

In addition, there are other strategies that have proven to be effective in anchoring sustainability in educational institutions in the long term. A clear vision and a strategically sound management approach are fundamental prerequisites. Managers in educational institutions must develop a long-term strategy that considers sustainability as an integral part of institutional goals and consistently pursues appropriate measures.31 In times of scarce resources, strategic alliances with external partners can help to overcome resource bottlenecks and support the implementation of sustainable projects.31 In addition, incentive systems can be created that promote further training and employee engagement in the area of sustainability.[cxv]

Ultimately, a deep understanding of the drivers and obstacles of change processes is essential for the success of such initiatives106. This individual knowledge makes it possible to make informed strategic decisions and develop specific tools that enable professionals to successfully integrate sustainable practices in different contexts. Only through such an informed approach can educational institutions actively contribute to societal transformation towards more sustainability.

References

[i] Aisenson, G., Legaspi, L. P. M., Valenzuela, V., Czerniuk, R., Miguelez, V. V., Moulia, L., Larriba, G., Solano, L. & Alonso, D. E. Guidance and education, an analysis of young peoples’ discontinuous school pathways: the guidance-oriented approach of educational institutions. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guidance 22, 739–758 (2022).

[ii] Schuller, T. & Desjardins, R. Understanding the social outcomes of learning (Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development, 2007).

[iii] Neyer, F. & Asendorpf, J. Psychologie der Persönlichkeit (Springer, 2018).

[iv] Sadh, V. G. Green Technology in Education: Key to Sustainable Development. Proceedings of Recent Advances in Interdisciplinary Trends in Engineering & Applications (RAITEA) (2019).

[v] Pleśniarska, A. Monitoring progress in “quality education” in the European Union – strategic framework and goals. Int. J. Sustain. High Educ. 20, 1125-1142 (2019).

[vi] Tabelle 2.1.9 – Datenportal des BMBF. Datenportal des Bundesministeriums für Bildung und Forschung – BMBF. Retrieved on 31/08/2024: https://www.datenportal.bmbf.de/portal/de/Tabelle-2.1.9.html. (n.d.).

[vii] Kuhl Teles, V. & Andrade, J. Public investment in basic education and economic growth. J. Econ. Stud. 35, 352-364 (2008).

[viii] Goczek, Ł., Witkowska, E. & Witkowski, B. How Does Education Quality Affect Economic Growth? Sustainability 13, 6437 (2021).

[ix] Kurihara, Y. Which Types of Education are Important for Economic Growth? Res. Appl. Econ. 11, 1 (2019).

[x] Mulà, I. et al. Catalysing change in Higher Education for Sustainable Development. Int. J. Sustain. High Educ. 18, 798–820 (2017).

[xi] Europäische Kommission, Generaldirektion Bildung, Jugend, Sport und Kultur. Erasmus+ annual report 2020 (Amt für Veröffentlichungen der Europäischen Union, 2021).

[xii] Strachan, S., Logan, L., Willison, D., Bain, R., Roberts, J., Mitchell, I. & Yarr, R. Reflections on developing a collaborative multi-disciplinary approach to embedding education for sustainable development into higher education curricula. Emerald Open Res. 1, 9 (2023).

[xiii] United Nations. Implementation UNECE Strategy for ESD across the ECE Region. Retrieved on 31/08/2024: https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2022-09/Implementation of the UNECE Strategy_web_final_05.09.2022.pdf (n.d.).

[xiv] de Villiers, C., Kuruppu, S. & Dissanayake, D. A (new) role for business – Promoting the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals through the internet-of-things and blockchain technology. Journal of Business Research 131, 598–609 (2021).

[xv] Kazaure, J. S. & Matthew, U. O. Multimedia E-Learning Education in Nigeria and Developing Countries of Africa for Achieving SDG4. International Journal of Information Communication Technologies and Human Development (2020).

[xvi] BMZ. Armut. Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung. Retrieved on 31/08/2024: https://www.bmz.de/de/service/lexikon/armut-14038. (n.d.).

[xvii] Ty, R. Pedagogy and Curriculum to Prevent and Counter Violent Extremism: Human Rights, Justice, Peace, and Democracy. (2020).

[xviii] Demirbağ, İ. & Sezgin, S. Book Review: Guidelines on the Development of Open Educational Resources Policies. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 22, 261–263 (2021).

[xix] Briones Alonso, E., Molenaers, N., Vandenbroucke, S. & Van Ongevalle, J. SDG Compass Guide: Practical Frameworks and Tools to Operationalise Agenda 2030. (2021).

[xx] Elmassah, S., Biltagy, M. & Gamal, D. Framing the role of higher education in sustainable development: a case study analysis. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 23, 320–355 (2021).

[xxi] United Nations. Higher Education Sustainability Initiative | Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Retrieved on 31/08/2024: https://sdgs.un.org/HESI (n.d.).

[xxii] Saini, M., Sengupta, E., Singh, M., Singh, H. & Singh, J. Sustainable Development Goal for Quality Education (SDG 4): A study on SDG 4 to extract the pattern of association among the indicators of SDG 4 employing a genetic algorithm. Educ Inf Technol 28, 2031–2069 (2023).

[xxiii] Peters, G. F., Romi, A. M. & Sanchez, J. M. The Influence of Corporate Sustainability Officers on Performance. J Bus Ethics 159, 1065–1087 (2019).

[xxiv] Fekih Zguir, M., Dubis, S. & Koç, M. Embedding Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) and SDGs values in curriculum: A comparative review on Qatar, Singapore and New Zealand. Journal of Cleaner Production 319, 128534 (2021).

[xxv] Olsson, D., Gericke, N. & Boeve-de Pauw, J. The effectiveness of education for sustainable development revisited – a longitudinal study on secondary students’ action competence for sustainability. Environmental Education Research 28, 405–429 (2022).

[xxvi] Valls-Val, K. & Bovea, M. D. Carbon footprint in Higher Education Institutions: a literature review and prospects for future research. Clean Techn Environ Policy 23, 2523–2542 (2021).

[xxvii] Lertpratchya, A. P., Besley, J. C., Zwickle, A., Takahashi, B. & Whitley, C. T. Assessing the role of college as a sustainability communication channel. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 18, 1060–1075 (2017).

[xxviii] Carol Adams. The role of leadership and governance in transformational change towards sustainability. Retrieved on 31/08/2024: https://drcaroladams.net/the-role-of-leadership-and-governance-in-transformational-change-towards-sustainability/. (n.d.).

[xxix] Araç, S. K. & Madran, C. Business school as an initiator of the transformation to sustainability: A content analysis for business schools in PRME. Social Business 4, 137–152 (2014).

[xxx] Schröder, S., Wiek, A., Farny, S. & Luthardt, P. Toward holistic corporate sustainability—Developing employees’ action competence for sustainability in small and medium-sized enterprises through training. Business Strategy and the Environment 32, 1650–1669 (2023).

[xxxi] Chakraborty, A., Kumar, S., Shashidhara, L. S. & Taneja, A. Building Sustainable Societies through Purpose-Driven Universities: A Case Study from Ashoka University (India). Sustainability 13, 7423 (2021).

[xxxii] Geng, Y., Liu, K., Xue, B. & Fujita, T. Creating a “green university” in China: a case of Shenyang University. Journal of Cleaner Production 61, 13–19 (2013).

[xxxiii] Helmers, E., Chang, C. C. & Dauwels, J. Carbon footprinting of universities worldwide: Part I—objective comparison by standardized metrics. Environ Sci Eur 33, 30 (2021).

[xxxiv] Berkeley Center for Green Chemistry. Greener Solutions | Berkeley Center for Green Chemistry. Retrieved on 31/08/2024: https://bcgc.berkeley.edu/education/greener-solutions (n.d.).

[xxxv] Sustainability, H. O. for. How We Power. Harvard Office for Sustainability. Retrieved on 31/08/2024: https://sustainable.harvard.edu/our-plan/how-we-power/. (n.d.).

[xxxvi] Sarwar, S., Streimikiene, D., Waheed, R. & Mighri, Z. Revisiting the empirical relationship among the main targets of sustainable development: Growth, education, health and carbon emissions. Sustainable Development 29, 419–440 (2021).

[xxxvii] Rieckmann, M. Developing and Assessing Sustainability Competences in the Context of Education for Sustainable Development. in Education for Sustainable Development in Primary and Secondary Schools: Pedagogical and Practical Approaches for Teachers (ed. Karaarslan-Semiz, G.) 191–203 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2022).

[xxxviii] Rieckmann. Learning to transform the world: key competencies in education for sustainable development – UNESCO Digital Library. Retrieved on 31/08/2024: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000261802. (n.d.).

[xxxix] Muff, K., Kapalka, A. & Dyllick, T. The Gap Frame – Translating the SDGs into relevant national grand challenges for strategic business opportunities. The International Journal of Management Education 15, 363–383 (2017).

[xl] Kim, M., Albers, N. D., Knotts, T. L. & Kim, J. Sustainability in Higher Education: The Impact of Justice and Relationships on Quality of Life and Well-Being. Sustainability 16, 4482 (2024).

[xli] Wang, Y., Sommier, M. & Vasques, A. Sustainability education at higher education institutions: pedagogies and students’ competences. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 23, 174–193 (2022).

[xlii] Smith-Sebasto, N. J. The effects of an environmental studies course on selected variables related to environmentally responsible behavior. The Journal of Environmental Education 26, 30–34 (1995).

[xliii] O’Grady, M. Transformative education for sustainable development: A faculty perspective. Environ Dev Sustain (2023).

[xliv] Scharlemann, S. J. P. et al. Towards understanding interactions between Sustainable Development Goals: the role of environment–human linkages. Sustainability Science 15, 1573–1584 (2020).

[xlv] BMZ. SDG 8: Menschenwürdige Arbeit und Wirtschaftswachstum. Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung. Retrieved on 31/08/2024: https://www.bmz.de/de/agenda-2030/sdg-8 (n.d.).

[xlvi] Ghardallou, W. Corporate Sustainability and Firm Performance: The Moderating Role of CEO Education and Tenure. Sustainability 14, 3513 (2022).

[xlvii] Paula, I. C. de, Campos, E. A. R. de, Pagani, R. N., Guarnieri, P. & Kaviani, M. A. Are collaboration and trust sources for innovation in the reverse logistics? Insights from a systematic literature review. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 25, 176–222 (2019).

[xlviii] Willness, C. R., Boakye-Danquah, J. & Nichols, D. R. How Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation Can Enhance Community-Engaged Teaching and Learning. Academy of Management Learning & Education 22, 112–131 (2023).

[xlix] Dahl, A. L. Achievements and gaps in indicators for sustainability. Ecological Indicators 17, 14–19 (2012).

[l] Ramos, T. B. & Caeiro, S. Meta-performance evaluation of sustainability indicators. Ecological Indicators 10, 157–166 (2010).

[li] McCool, S. F. & Stankey, G. H. Indicators of Sustainability: Challenges and Opportunities at the Interface of Science and Policy. Environmental Management 33, 294–305 (2004).

[lii] Décamps, A., Barbat, G., Carteron, J.-C., Hands, V. & Parkes, C. Sulitest: A collaborative initiative to support and assess sustainability literacy in higher education. The International Journal of Management Education 15, 138–152 (2017).

[liii] Tavanti, M. Assessing and Measuring Sustainability Impact. in Developing Sustainability in Organizations: A Values-Based Approach (ed. Tavanti, M.) 453–473 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2023).

[liv] Can, Ö. Corporate Sustainability Performance. in Encyclopedia of Sustainable Management (eds. Idowu, S. et al.) 1–8 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2020).

[lv] Kioupi, V. & Voulvoulis, N. Education for Sustainable Development: A Systemic Framework for Connecting the SDGs to Educational Outcomes. Sustainability 11, 6104 (2019).

[lvi] Lozano, R., Lukman, R., Lozano, F. J., Huisingh, D. & Lambrechts, W. Declarations for sustainability in higher education: becoming better leaders, through addressing the university system. Journal of Cleaner Production 48, 10-19. (2013).

[lvii] Haugh, H. M. & Talwar, A. How Do Corporations Embed Sustainability Across the Organization? Academy of Management Learning & Education 9, 3, 384-396. (2010).

[lviii] Joseph, G. Ambiguous but tethered: An accounting basis for sustainability reporting. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 23, Issue 2, 93-106. (2012).

[lix] ECA. ECA Sustainability report 2021. Retrieved on 31/08/2024: https://www.eca.europa.eu/Lists/ECADocuments/ECA_Sustainability_Report_2021/ECA_Sustainability_Report_2021_EN.pdf (2022)

[lx] Adams, C. A. & Frost, G. Integrating sustainability reporting into management practices. Accounting Forum 32, 4, 288-302. (2008).

[lxi] Mercedes-Benz Group. Sustainability Report 2023. Retrieved on 31/08/2024: https://group.mercedes-benz.com/documents/sustainability/reports/mercedes-benz-sustainability-report-2023.pdf (2024).

[lxii] EDEKA Group. (2024). Annual Report 2023 EDEKA Group. Retrieved on 31/08/2024: https://verbund.edeka/verbund/edeka_group_company_report_2023__english_version.pdf (2024).

[lxiii] Lubinger, M., Frei, J. & Greiling, D. Assessing the materiality of university G4-sustainability reports. Journal of Public Budgeting 31, 3, 364-391. (2019).

[lxiv] Alghamdi, N., den Heijer, A. & de Jonge, H. Assessment tools’ indicators for sustainability in universities: an analytical overview. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 18, 1, 84-115. (2017).

[lxv] University of Cambridge. Environmental Sustainability Report 2022/2023. Retrieved on 31/08/2024: https://www.environment.admin.cam.ac.uk/sites/www.environment.admin.cam.ac.uk/files/annual_environmental_sustainability_report_2022-23_final_version_1.pdf (2024).

[lxvi] Tejedor, G., Segalàs, J., Barrón, Á., Fernández-Morilla, M., Fuertes, M. T., Ruiz-Morales, J., Gutiérrez, I., García-González, E., Aramburuzabala, P., & Hernández, À. Didactic strategies to promote competencies in sustainability. Sustainability, 11(7), 2086. (2019).

[lxvii] Bourdeau, J. & Balacheff, N. Technological and Social Environments for Interactive Learning. Santa Rosa, California : Informing Science (2014)

[lxviii] Kirkwood, A., & Price, L. Technology-enhanced learning and teaching in higher education: what is ‘enhanced’ and how do we know? A critical literature review. Learning, Media and Technology 39(1), 6–36. (2013).

[lxix] González-Zamar M-D, Abad-Segura E, López-Meneses E & Gómez-Galán J. Managing ICT for Sustainable Education: Research Analysis in the Context of Higher Education. Sustainability 12(19), 8254. (2020).

[lxx] Orantes-Jiménez, S., Zavala-Galindo, A. & Vázquez-Álvarez, G. Paperless Office: A New Proposal for Organizations. Journal of Systemics 13, 3, 47-55 (2015).

[lxxi] Statista. Consumption of paper and cardboard worldwide from 1961 to 2022. Retrieved on 31/08/2024: https://www.statista.com/statistics/270319/consumption-of-paper-and-cardboard-since-2006/ (n.d.).

[lxxii] Jampala, M. B. & Shivnani, T. A step towards sustainable development in higher education in India by implementing new media technologies: A paperless approach. World Journal of Science, Technology and Sustainable Development 16, 2, 94-100. (2019).

[lxxiii] Tatlı HS, Bıyıkbeyi T, Gençer Çelik G & Öngel G. Paperless Technologies in Universities: Examination in Terms of Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT). Sustainability 16(7), 2692. (2024).

[lxxiv] Fountain, J. E. Building the virtual state: Information technology and institutional change. Rowman & Littlefield (2004).

[lxxv] Bower, H. H. On Emulating Classroom Discussion in a Distance-Delivered OBHR Course: Creating an On-Line Learning Community. Academy of Management Learning & Education 2, 1, 22-36. (2003).

[lxxvi] Findik-Coşkunçay, D., Alkış, N., Özkan-Yıldırım, S. A Structural Model for Students’ Adoption of Learning Management Systems: An Empirical Investigation in the Higher Education Context. Educational Technology & Society 21, 2, 13-27. (2018).

[lxxvii] Morioka, S. M., Holgado, M., Evans, S., Carvalho, M. M., Rotella Junior, P. & Bolis, I. Two-Lenses Model to Unfold Sustainability Innovations: A Tool Proposal from Sustainable Business Model and Performance Constructs. Sustainability 14(1), 556. (2022).

[lxxviii] Shriberg, M. Institutional assessment tools for sustainability in higher education: Strengths, weaknesses, and implications for practice and theory. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 3, 3, 254 270. (2002).

[lxxix] Sayed, A., Kamal, M. & Asmuss, M. Benchmarking tools for assessing and tracking sustainability in higher educational institutions: Identifying an effective tool for the University of Saskatchewan. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 14, 4, 449-465. (2013).

[lxxx] Gómez, F. U., Sáez-Navarrete, C., Lioi, S. R. & Marzuca, V. I. Adaptable model for assessing sustainability in higher education. Journal of Cleaner Production 107, 475-485. (2015).

[lxxxi] Environmental Management System. Cam.ac.uk. Retrieved on 31/08/2024: https://www.environment.admin.cam.ac.uk/EMS (n.d.).

[lxxxii] Environmental management system – sustainability. University of Liverpool. Retrieved on 31/08/2024: https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/sustainability/strategy-and-performance/environmental-management-system/ (2024).

[lxxxiii] BMW Group. Sustainability & Responsibility. Retrieved on 31/08/2024: https://www.bmwgroup.com/en/sustainability/employees.html(n.d.).

[lxxxiv] BMW Group. BRIDGE. Retrieved on 31/08/2024: https://www.bmwgroup.com/de/news/allgemein/2024/unicef-partnerschaft-bridge.html (n.d.).

[lxxxv] Kaufmann, T. Strategiewerkzeuge aus der Praxis: Analyse und Beurteilung der strategischen Ausgangslage (2021).

[lxxxvi] Hungenberg, H. Strategisches Management in Unternehmen: Ziele – Prozesse – Verfahren (Springer Gabler, 2014).

[lxxxvii] Bergmann, R. & Bungert, M. Strategische Unternehmensführung: Perspektiven, Konzepte, Strategien (Springer Gabler, 2022).

[lxxxviii] Aleixo, A. M., Leal, S. & Azeiteiro, U. M. Conceptualization of sustainable higher education institutions, roles, barriers, and challenges for sustainability: an exploratory study in Portugal. J. Clean. Prod. 172, 1664-1673 (2018).

[lxxxix] Selim, M. Skilled based education is the key to sustainable development. Second International Sustainability and Resilience Conference: Technology and Innovation in Building Designs 1-4 (2020).

[xc] Abubakar, I., Al-Shihri, F. & Ahmed, S. Students’ assessment of campus sustainability at the university of dammam, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 8, 59 (2016).

[xci] Bourn, D., Hunt, F., Blum, N. & Lawson, H. Primary education for global learning and sustainability (Cambridge Primary Review Trust, 2016).

[xcii] Bilodeau, L., Podger, J. & Abd-El-Aziz, A. Advancing campus and community sustainability: strategic alliances in action. Int. J. Sustain. High Educ. 15, 157-168 (2014).

[xciii] Hancock, L. & Nuttman, S. Engaging higher education institutions in the challenge of sustainability: sustainable transport as a catalyst for action. J. Clean. Prod. 62, 62-71 (2014).

[xciv] European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Directive (EU) 2022/2464 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 amending Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Directive 2013/34/EU, as regards corporate sustainability reporting. Off. J. Eur. Union L 322, 15-80 (2022).

[xcv] PwC. PwC-Umfrage: Führungskräfte sehen das Nachhaltigkeitsreporting zunehmend als Chance. Retrieved on 31/08/2024: https://www.pwc.de/de/pressemitteilungen/2024/pwc-umfrage-fuehrungskraefte-sehen-das-nachhaltigkeitsreporting-zunehmend-als-chance.html (2024).

[xcvi] Klimaschutz- und Energieagentur Niedersachsen. Förderprogramme für Bildungsträger. Retrieved on 31/08/2024: https://www.klimaschutz-niedersachsen.de/foerderprogramme/bildungstraeger/index.php (n.d.).

[xcvii] Greve, H. R. Microfoundations of management: Behavioral strategies and levels of rationality in organizational action. Acad. Manag. J. 56, 387-410 (2013).

[xcviii] Wilmers, A. From the global to the school level: connections and contradictions between Fridays for Future and the school context. J. Sustain. Educ. 28 (2023).

[xcix] Too, L. & Bajracharya, B. Sustainable campus: engaging the community in sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High Educ. 16, 57-71 (2015).

[c] Gong, M., Gao, Y., Koh, L., Sutcliffe, C. & Cullen, J. The role of customer awareness in promoting firm sustainability and sustainable supply chain management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 217, 88-96 (2019).

[ci]Weiss, M., Barth, M., Wiek, A. & von Wehrden, H. Drivers and barriers of implementing sustainability curricula in higher education – Assumptions and evidence. High Educ. Stud. 11, 42-64 (2021).

[cii]George, G., Schillebeeckx, S. J. D. & Liak, T. L. The management of natural resources: An overview and research agenda. Acad. Manag. J. 58, 1595-1613 (2015).

[ciii] Khumalo, S. S. A Descriptive Analysis of the Leadership Practices of Primary School Principals in Promoting Sustainability Through Motivating Teachers. Discourse Commun. Sustain. Educ. 11, 45-61 (2020).

[civ] Salvioni, D. M., Franzoni, S. & Cassano, R. Sustainability in the higher education system: an opportunity to improve quality and image. Sustainability 9, 914 (2017).

[cv] Soares, G. G., Braga, V. L. S., Marques, C. S. E. & Ratten, V. Corporate entrepreneurship education’s impact on family business sustainability: A case study in Brazil. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 19, 100424 (2021).

[cvi] Blanco-Portela, N., Benayas, J., Pertierra, L. R. & Lozano, R. Towards the integration of sustainability in Higher Education Institutions: A review of drivers of and barriers to organisational change and their comparison against those found of companies. J. Clean. Prod. 166, 563-578 (2017).

[cvii] Barth, M. Many roads lead to sustainability: a process-oriented analysis of change in higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High Educ. 14, 160-175 (2013).

[cviii]Ralph, M. & Stubbs, W. Integrating environmental sustainability into universities. High Educ. 67, 71-90 (2014).

[cix] Hunt, F. Global Learning in Primary Schools in England: Practices and Impacts. DERC Research Paper no. 9 (UCL Institute of Education, 2012).

[cx] Wright, T. S. A. & Wilton, H. Facilities management directors’ conceptualizations of sustainability in higher education. J. Clean. Prod. 31, 118-125 (2012).

[cxi] Maiorano, J. & Savan, B. Barriers to energy efficiency and the uptake of green revolving funds in Canadian universities. Int. J. Sustain. High Educ. 16, 200-216 (2015).

[cxii] Gioia, D. A. & Corley, K. G. Being good versus looking good: Business school rankings and the Circean transformation from substance to image. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 1, 107-120 (2002).

[cxiii] Foster, J. in Schooling for Sustainable Development in Canada and the United States (eds McKeown, R. & Nolet, V.) 263-275 (Springer, 2013).

[cxiv] Buckler, C. & MacDiarmid, A. in Schooling for Sustainable Development in Canada and the United States (eds McKeown, R. & Nolet, V.) 95-108 (Springer, 2013).

[cxv] Hueske, A.-K. & Guenther, E. Multilevel barrier and driver analysis to improve sustainability implementation strategies: Towards sustainable operations in institutions of higher education. J. Clean. Prod. 291, 125899 (2021).