Authors: Einemann, Sokoli, Baars, August 31, 2024

1 Definition and Relevance

The Paris Agreement has given international climate policy a new goal: net zero emissions. Article 4 of the treaty signed in 2015 states accordingly:

“In order to achieve the long-term temperature goal set out in Article 2 [Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C], Parties aim […] to achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century” (p. 4).1

It is precisely this balance of anthropogenic emissions that describes the idea of net zero emissions. However, there is no standardised definition for this term and there are many similar terms such as climate neutral, carbon neutral, climate positive and carbon negative. This article deals with net zero emissions, which Allen et al. (2022) define as follows:

“The term net zero emissions means a balance between ongoing anthropogenic release of greenhouse gases (GHGs) into the atmosphere and active GHG removal either through direct capture and disposal or anthropogenically enhanced natural removal processes: The term may be applied to an individual gas, such as CO2, or a basket of gases combined using a GHG metric” (p. 876).2

1.1 Introduction to net zero emissions

Climate policy based on the concept of net zero emissions is increasingly linked to a specific target year by which a city or country should achieve this goal. The idea behind this is that there is a finite budget of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases that may be released into the atmosphere. This fixed budget is directly linked to meeting the 1.5-degree target and implies that CO2 emissions must fall to net zero globally by 2050. If anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions stop, then the global warming driven by them will also stop.3 In order for temperatures on Earth to stabilise sustainably, it is also important that man-made carbon flows in and out of each sphere – i.e. lithosphere, atmosphere and land and ocean biosphere – are balanced, as biological sinks such as forests, for example, cannot continue to absorb CO2 indefinitely.2

While scientists calculate the carbon budget for the global atmosphere, these implications need to be translated into individual decarbonisation pathways for countries, sub-national entities, companies and other organisations. More than 120 countries have pledged to reach net zero in one way or another by the middle of the century, consistent with the goals set out in the Paris Agreement. Among them are the three largest greenhouse gas emitters China, the European Union (EU) and the United States. In addition, about 20% of the companies on the Forbes Global 2000 list have already set voluntary net zero targets.3

The inconsistent approach to the concept of net zero leads to several problems with the individual decarbonisation strategies of countries and companies. While some plans only consider CO2 emissions, others include all greenhouse gas emissions in their calculations. Furthermore, there is no consensus on which scope of emissions should be included in the emissions targets. In some cases, only emissions that can be directly influenced (scope 1 emissions) are considered, while in other cases, upstream and downstream emissions from the supply chain, such as raw material suppliers and the end users of the product, are also considered (scope 2 and 3 emissions). Another key question is whether the aim is to reduce emissions or offset them through other activities without the product or process having caused zero emissions. There is also a debate about whether there should be country- and industry-specific targets. For example, the question arises as to whether very polluting or energy-intensive industries should achieve net zero before less polluting or less energy-consuming ones. Finally, it should not be forgotten that emission reductions should not unintentionally lead to other negative environmental impacts.4,5 To address the vagueness inherent in the idea of net zero, Frankhauser et al. (2021) summarised seven attributes that a successful net zero framework should include.

1.2 Seven attributes of a successful net zero framework

Firstly, there are sound scientific and economic reasons for reducing greenhouse gas emissions as much and as quickly as possible. The advantage is that the option remains to further tighten the remaining carbon budgets in the light of new scientific evidence. Economic modelling has shown that early deployment of climate action, coupled with long-term planning over several years, is the most cost-effective way to achieve a given temperature target. To encourage early emission reductions, governance experts recommend combining long-term net zero commitments – which set the direction – with short-term targets that define emission pathways over decision-relevant time horizons.3

Secondly, net zero means tackling all emissions. On the one hand, the cost of renewable energy has fallen so much that the transition to carbon-free electricity is almost unstoppable. On the other hand, in most other sectors, the transition to zero carbon is still uncertain, as carbon-free solutions exist but are still costly and not yet well established. Therefore, net zero is about extending the focus to ‘harder to treat’ sectors. Furthermore, tackling all emissions requires an equally comprehensive approach to stakeholder engagement.3

Thirdly, net zero should combine a very low level of residual emissions with a low level of multi-decadal removals. Carbon dioxide removal is likely to be constrained by cost considerations and geopolitical factors, as well as biological, geological, technological and institutional limitations on our capability to remove carbon from the atmosphere and store it permanently and safely. There are also concerns about an over-reliance on carbon removal strategies that allow ‘business as usual’ rather than a drastic reduction in fossil fuel use.3

Fourthly, effective regulation of carbon offsets is required. Experience to date with carbon offset markets shows that the environmental integrity of carbon offsets will be problematic unless quality standards are improved and rigorously enforced. As only very few organisations and not even all countries will be able to balance residual emissions and removals to sinks themselves, systems are needed that can establish a global balance between sources and sinks.3

The last three attributes are about compatibility with the objectives of sustainable development. The burden of achieving the global climate target should be shared fairly across and within countries (e.g. between regions, industries and population groups). It must be ensured that carbon removals (e.g. through nature-based solutions) support rather than hinder a just transition to a zero-carbon society. Furthermore, net zero must not only pursue a single goal – carbon storage – but must recognise a whole range of ecosystem services and be embedded in broader strategies for socio-ecological sustainability. Nature-based solutions must be biodiversity-based and human-driven. In addition, net zero can also be seen as an economic opportunity. Carbon-free investments can lead to the elimination of economically damaging market and policy failures and create a positive cycle of investment, renewal and growth in the long term.3

In essence, it can be said that a transformation to net zero is necessary to comply with the Paris Agreement. This goal can be achieved through the interplay of three strategies: comprehensive emission reductions and, for unavoidable emissions, carbon dioxide removals and carbon offsetting (see figure 1). Aspects of ecological, social and economic sustainability should not be lost sight of.

2 Historical background

According to the literature, the term “net zero” is most commonly used in the context of renewable energy and the built environment, such as net zero buildings. The first use of the term “net zero” was in 1957, in the field of physics, where it referred to “net-zero-field mobility,” which is unrelated to environmental concerns. In 1991, it was first mentioned in relation to net zero CO2 emissions, specifically concerning the greenhouse effect and other greenhouse gas emissions in tropical regions. This usage arose from discoveries that deforestation and biomass fuel burning in the Amazon were three to five times greater than previously estimated. The Paris Agreement significantly amplified the term “net zero,” encouraging countries to achieve net zero emissions by mid-century.6

2.1 Net Zero History Stages

The development of the concept of net zero over the years can be divided into four distinct periods: Net Zero in the early stages of the climate regime (1991-2004), The Kyoto Protocol (2005-2011), The Paris Agreement (2012-2015) and Post Paris implementation.7

2.1.1 Net Zero in the early stages of the climate regime (1991-2004)

In 1992, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) mandated

“[…] Stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system […]” (p. 4).8

This statement represented one of the initial steps in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. However, it did not yet address balancing emissions and removals, nor did it set any specific targets. The statement focused on reduction and was quite broad, aiming to mitigate human-caused impacts on the climate system. This UN definition served as an effective catalyst for promoting other terms related to emission reduction or balancing.7

In the Kyoto Protocol of the year 1997 it was agreed:

“The Parties included […] shall, individually or jointly, ensure that their aggregate anthropogenic carbon dioxide equivalent emissions of the greenhouse gases […] do not exceed their assigned amounts, calculated pursuant to their quantified emission limitation and reduction commitments […], and in accordance with the provisions of this Article, with a view to reducing their overall emissions of such gases by at least 5 percent below 1990 levels in the commitment period 2008 to 2012” (p. 4).9

Kyoto Protocol according to this statement was quite significant as it allowed countries to set targets for limiting and reducing emissions, using 1990 as the baseline year. This was a key advancement compared to the 1992 UNFCCC statement, which lacked such specific provisions.

2.1.2 The Kyoto Protocol (2005-2011)

A milestone in climate policy was the come into force of Kyoto Protocol in 2005, which set a course towards net zero. The idea of net zero began to be divided into specific targets, even for some different sector.7 During the Kyoto Protocol, three market-based mechanisms were included to achieve the targets of the protocol: Emission Trading, Joint Implementation, and the Clean Development Mechanism.10 The Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) is defined in the Article 12 of Kyoto Protocol as:

“The purpose of the clean development mechanism shall be to assist Parties not included in Annex I in achieving sustainable development and in contributing to the ultimate objective of the Convention, and to assist Parties included in Annex I in achieving compliance with their quantified emission limitation and reduction commitments under Article 3” (p.11).11

The Kyoto Protocol of 1997 came into force in 2005 under the umbrella of the convention, while the CDM implementation began in 2006.12 The Kyoto Protocol was highly significant because it assigned economic value to emission reductions. The CDM allows developing countries to earn Certified Emission Reductions (CERs) equivalent to one tonne of CO2. This enables developed countries to buy or sell these CERs to meet their emission reduction targets.10

Another concept that emerged during this period was the Net Zero Energy Building (NZEB), which demonstrated how targets could shape policies and subsequently their implementation. This concept refers to buildings that generate as much energy as they consume. Many developed countries began setting targets for their implementation, starting with the UK in 2006, aiming for Zero-Carbon homes by 2016. The US Department of Energy created a Net-Zero Energy Commercial Building Initiative with specific targets for all newly constructed commercial buildings to be net zero by 2040. Similarly, the EU adopted the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive to achieve NZEBs.7

2.1.3 The Paris Agreement (2012-2015)

This period is highly significant in the use of the term “net zero”. The results from member states under the Kyoto Protocol were found to be untenable, as they were not meeting the targets required by the protocol. Consequently, scientists began seeking ways to translate temperature goals into specific targets to achieve net zero emissions. In 2011, it was decided to convene an agreement to set these targets, which would take place in 2015 in Paris, known as the Paris Agreement.7

During the United Nations Paris Climate Agreement, 197 countries agreed to align their policies to limit global warming to well below 2°C above preindustrial levels degrees Celsius, with efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C. To achieve them, the target was to reduce the carbon budget by 2030, so the emissions would be 45% below the 2010 level, and achieve net zero by 2050, which significantly highlights the concept of net zero. It is important to understand that net zero is not just a scientific term but also a reference point for reducing climate change. This has operational implications for both the economy and society, and it drives changes in technology, politics, and legal frameworks.3

2.1.4 Post Paris implementation

This period is crucial in achieving net zero targets. The Paris Agreement served as a pivotal event, leading to the surge of net zero pledges.7 One of the requirements of the Paris Agreement is for parties to submit a report with their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). According to the United Nations, NDC is a strategy to adapt to the impacts of climate change and to reduce emission. This report includes plans detailing how the parties are achieving their targets for mitigating greenhouse gases and serves as a mechanism for monitoring progress. Each party of the Paris Agreement is required to create a NDC and to revise it every five years.13

The Paris Agreement requested the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to prepare a report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C. In 2018, the IPCC published the ‘Special Report’ and ‘Summary for Policymakers’ on Global Warming of 1.5°C, which are crucial for the implementation of net zero. The ‘Summary for Policymakers’ was drafted by the authors and approved by IPCC with delegates of 195 IPPC member states.14 The special report also emphasized the importance of reducing CO2 emissions and achieving net zero by 2050.15

In 2017, only 22 countries had considered or were considering net zero pledges. However, the publication of the IPCC Report in 2018 helped bring the term “net zero” from the environmental sphere into the political arena. Consequently, in December 2018, the EU committed to achieve net zero GHG by 2050, calling this initiative the Green Deal and subsequently developing policies to achieve this target. In 2019, UN Secretary-General António Guterres called on the governments to submit their plans for achieving the 2050 target.14

From 31 October – 13 November 2021, the Glasgow Climate Change Conference, or COP26, took place after being postponed by a year due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Significant decisions were made at this event, such as reducing coal energy use and eliminating inefficient subsidies for fossil fuels. By COP26, only 153 countries had submitted their NDCs, covering approximately 49% of global GHG emissions and according to estimations, global warming is projected to reach 2.7°C by 2100. Global warming of 2.7°C could be reduced by 0.5°C with the help of net zero pledges.16 If NDCs or net zero pledges had been fulfilled before COP26, it was projected that by 2100, global warming would range between 1.8°C and 2.5°C according to estimates. It was decided that NDC reports would be submitted every ten years, with updates every five years.17

Notable statements during COP26 included those from leaders like U.S. President Joe Biden, who announced a long-term target for the USA to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 and to quadruple US climate finance by 2024. Another significant declaration came from Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who committed India to achieving net zero emissions by 2070.17

These pledges play a fundamental role, as by May 2023, 88% of global emissions were covered by such commitments. Beyond the political sphere, these pledges also influence corporate measurements to align with the Paris Agreement. 7More than 120 countries have committed to achieving net zero targets, including major emitters like the USA, China, and the EU.3

2.2 Corporate History

Corporations and states aim to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement. Corporations can reduce emissions both directly and through their supply chains. For example, the Swedish retail giant IKEA has set a target to become net zero across its entire value chain by 2050. Microsoft has committed to being net zero by 2050 in CO2 emissions compared to its 1975 founding year. ACI Europe, representing around 500 airports across Europe, has pledged to achieve net zero emissions for airport buildings and ground operations by 2050, excluding emissions from flight.5

Corporations often choose to declare their net zero targets independently, but they can also be collective in the form of pledges, such as in the case of Climate Action 100+, and The Climate Pledge, which is focused on corporations, and Climate Action Tracker, which is focused on states, cities, and regions.18 Climate Action 100+ was established after the Paris Agreement in 2017 for companies to track emissions reductions based on net zero pledges.19

According to Forbes 2000, there are around 702 companies that have decided to achieve net zero targets. The sectors with the highest representation are the service industry (253 companies), the materials industry (73 companies), and the manufacturing industry (56 companies). In terms of distribution, there are 216 companies in the USA, 89 in Japan, 57 in the UK, 46 in France, and 32 in Germany. Among the companies included in the Forbes 2000, half of those headquartered in the EU have set net zero targets.20

3 Practical Implementation

This chapter presents possible processes, measures and tools to help companies achieve net zero emissions. As previously mentioned, achieving net zero is of significant relevance for companies due to various stakeholder demands, risk management considerations, and regulatory requirements. Therefore, the following section will first outline a general approach to implementing a net zero strategy in practice, followed by a more detailed elaboration. Given the recent development of net zero practices, new insights may emerge. This practical guide is based on the knowledge available as of August 2024.

3.1 General Approach Net Zero

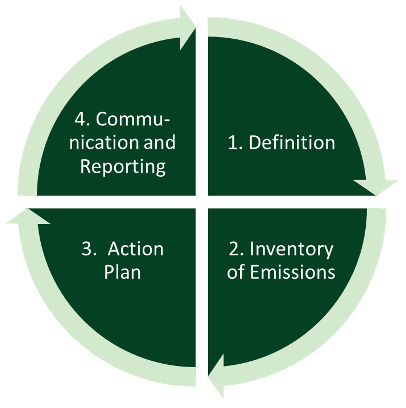

The practical implementation of net zero follows similar approaches to those used in modern project management. Initially, the strategic goal must be defined to transparently communicate the company’s direction to all stakeholders involved. Based on this goal, it becomes necessary to assess the current state. This involves determining the current emissions to identify the gap between the current state and the target state. Subsequently, an action plan is developed based on this gap analysis, aligning with the strategic goal. Also it is recommended to take a look at the step by step guide of the science based initiatives here.21

Throughout the implementation phase, communication and reporting play a crucial role. These ensure that regulatory reports are prepared on time and in accordance with formal requirements, while also addressing the information needs of stakeholders. The general process overview is illustrated in the following graphic.

3.1.1 Definition

Strategic planning focuses on establishing the parameters for the associated project. The goal here is to define the company’s specific commitment to achieving net zero, which may involve a phased target such as reaching net zero, or zero net emissions from business activities, by 2030 or 2050.22 Some prominent companies are pursuing even more ambitious goals, aiming to capture or transform more emissions than they produce, thereby becoming carbon negative. An example of such a company is Microsoft.23 In addition to setting a timeframe for achieving net zero, this goal should be made more tangible and measurable through key performance indicators (KPIs). The following KPIs can be applied.24

- Carbon Emissions Reduction

- Renewable Energy Usage

- Carbon Offsetting Level

- Energy Efficiency

For companies that have no prior experience in developing a net zero strategy, a good starting point is to focus on renewable energy usage. This can be effectively tested by referencing the current energy mix in electricity consumption, provided by your local energy supplier. The energy mix reports the CO2 emissions and can be used to calculate your emissions.25 Relevant KPIs should always be considered within the company’s specific context. For instance, the proportion of renewable energy in the energy mix is limited and could lead to supply constraints as demand increases.26Energy-intensive industries, such as the chemical industry, face greater challenges in reducing carbon emissions compared to traditional service companies.27 In service industries, a significant portion of carbon emissions may already be addressed through the increasing share of renewable energy in the energy mix.

3.1.2 Inventory of Emissions

A key question in sustainability reporting, particularly in frameworks such as the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), concerns the origin and magnitude of emissions. These metrics form the foundation for future reduction efforts. If a company has already conducted relevant measurements, these can be utilized. A separate inventory specifically for achieving net zero is not required, as the necessary data should be available under CSRD guidelines by 2025 and can be used accordingly. Emissions are categorized into Scope 1, 2, and 3 (see more at GHG Protocol). To inventory emissions, companies can use specialized software solutions. Alternatively, there is an Excel-based approach available on the GHG Protocol website.28

The result of the inventory represents the absolute target for emissions that need to be reduced or offset. In addition to establishing this target, the inventory provides an overview of the emissions associated with each source. This allows for the identification of major contributing factors and the implementation of quickly actionable reductions. The listed emissions can also be cross-referenced with the categories outlined in the chapter “Measures to reduce corporate emissions”, enabling the derivation of direct mitigation measures.

3.1.3 Action Plan

Building on this assessment, it is crucial to develop and prioritize reduction strategies. Priority should be given to actions with the highest impact potential, such as improving energy efficiency, transitioning to renewable energy sources, and optimizing supply chains. Energy management systems and platforms for procuring renewable energy, such as Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs), can facilitate the implementation of these strategies. The planning process should be transparent and follow a realistic timeline, adhering to general best practices. A prominent commercial tool currently available is Salesforce’s Net Zero Cloud, which integrates many aspects of the net zero journey.29 Additionally, free resources such as B Lab’s SDG Action Manager offer support, although this tool is designed to guide the broader Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) process rather than focusing exclusively on net zero targets 30. The University of Oxford’s “Netzeroclimate.org” provides a growing library of commonly used net zero tools, regularly updated to reflect the latest developments.31

For emissions that cannot be directly reduced, compensation strategies are employed. These include investments in projects aimed at CO2 sequestration or reduction, such as reforestation or Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS).

A successful net zero strategy must also be deeply integrated into daily business operations, necessitating adjustments across the entire value chain, particularly within the supply chain. Emissions categorized under Scope 3, which involve external entities over which a company has limited control, present a significant challenge.21 Simply switching suppliers is often not a feasible option, especially when alternatives are not readily available. This is particularly true for suppliers in countries that have not signed climate agreements and are unwilling or unable to provide the necessary emissions data. Practical approaches already in use include implementing a CO₂ fee per emitted ton or establishing a Code of Conduct for managing emissions across Scopes 1-3.32 Due to the fundamental importance of reducing emissions, this topic will be addressed in a dedicated section.

3.1.4 Communication and Reporting

Effective reporting and communication are crucial components of a net zero strategy, ensuring transparency, regulatory compliance, and stakeholder engagement. In the European Union, legal requirements such as the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) mandate that companies disclose detailed information on their environmental impact, including progress toward net zero targets.33 Under CSRD, companies must report their sustainability efforts, including emissions data across Scopes 1, 2, and 3, as well as their strategies and progress toward achieving net zero.33 These reports must meet rigorous standards for accuracy, timeliness, and transparency, ensuring they provide a clear and truthful account of the company’s environmental performance. Beyond legal obligations, external reporting serves to communicate the company’s net zero commitments to stakeholders, including investors, customers, and the public. Consistent and clear reporting helps build trust and demonstrates the company’s commitment to sustainability.33 Tools like sustainability reporting software (e.g., Enablon, Workiva) can streamline this process, ensuring compliance and effective communication. Internally, regular reporting is essential for monitoring progress toward net zero goals. This includes tracking key performance indicators (KPIs) related to emissions reductions, energy efficiency, and the implementation of mitigation strategies. Real-time dashboards and analytics tools can provide management with ongoing insights, enabling timely adjustments to strategies as needed. Internal communications should also focus on engaging employees at all levels, making them aware of the company’s net zero goals and their role in achieving them. Regular updates, training sessions, and internal campaigns can foster a culture of sustainability, ensuring that net zero objectives are embedded in daily operations.

3.2 Measures to reduce corporate emissions

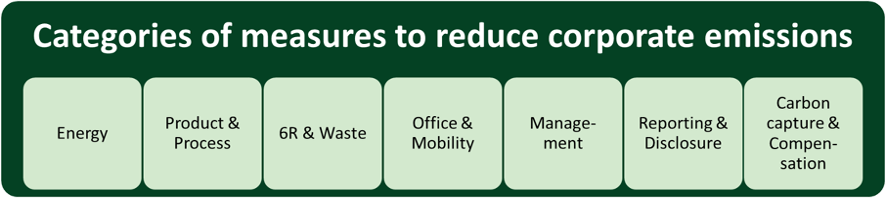

This chapter provides an overview of various measures that companies can take to achieve net zero emissions. In Chapter 1, three general strategies were discussed: comprehensive emission reductions and, for unavoidable emissions, carbon dioxide removals and carbon offsetting. These approaches will now be applied to corporate practice. The first type of emission reduction strategy represents the main part of the corporate options.

In 2023, Lewandowski and Ullrich attempted to compile a systematic and general overview from the literature on existing measures to reduce GHG emissions in companies (see figure 3). They note that no study has yet been found that focuses on reduction measures and concrete examples of implementation for a broad range of companies. In their paper, they not only summarise various measures for companies, but also examine the application and perceived effectiveness of these emission reduction measures (ERM) in companies. A total of 93 reports are included in the systematic literature review. In the following, the most important results for corporate practice will be illustrated based on these summaries.34

In the energy category, companies can fall back on five measures. In energy production, renewable energy can be produced with photovoltaics and energy storage can be used on buildings on site, for example. In energy acquisition, energy can be purchased from renewable, clean or low-carbon sources such as wind, biomass or geothermal energy. In energy efficiency, the efficiency of energy generation and technology can be increased. For example, more energy-efficient appliances and machines can be used. In terms of energy awareness, employees can be informed about energy-saving methods and their commitment can be increased. In energy recovery, heat pumps are used or processes such as waste heat recovery or integrated gasification combined cycle are introduced.34

There are a total of three measures in the product & process categories. Firstly, product adaptations, i.e. companies can redesign products to increase their lifespan and use renewable, recycled or less carbon-intensive materials. Secondly, process efficiency, i.e. efficiency is increased through process redesign, new equipment on machines or the use of by-products. Thirdly, the use or development of clean fuels, i.e. the efficiency of fuels and fuel consumption can be improved or low-carbon fuels such as biomass can be used.34

6R & waste comprises two corporate measures. Firstly, it involves applying the 6R principle throughout the organization. This includes reuse, recycling, reduction, recovery, redesign and remanufacturing. Secondly, it includes measures to reduce waste and appropriate waste disposal, such as the purification of used water.34

The office & mobility category includes three measures. Regarding communication, this can be made less carbon-intensive, e.g. by reducing paper consumption and holding online meetings and conferences instead of business trips. Regarding buildings, these can be modernised, and heating can be made more efficient. Here, more effective insulation or retrofitting and renovation with green products is an option. In terms of mobility, you can switch to less carbon-intensive modes of transport such as trains and bicycles instead of planes and cars and promote car sharing.34

There are seven measures in the management category. Incentives (e.g. financial rewards) can be created to promote low-carbon behaviour. Knowledge management also plays an important role. Information can be shared; stakeholders can be sensitised, and employees can be trained in low-carbon behaviour through workshops. In addition, measures in human resources can help to anchor sustainability in the organisational structure, for example by hiring a sustainability manager. There are also various management tools such as the use of quality control instruments, scenario analyses and risk management with a SWOT analysis, for example, to apply reduction measures. Best practice examples can also be used and benchmarking with competitors can take place. In addition, project management can be adapted to new regulations and technologies and decisions can be made on investments that support sustainability, e.g. by integrating emissions targets for new projects. Finally, stakeholder management can involve working with political decision-makers. Public-private partnerships (PPP) for energy-efficient investments are one option here.34

Companies can implement four measures for reporting & disclosure. Firstly, self-regulation means joining sustainable organisations, setting detailed reduction targets, measuring emissions accurately (e.g. according to the GHG Protocol) and communicating the results. Secondly, reporting systems can be used. This software is used to improve overall efficiency. An example of this is the use of a greenhouse gas management system. Thirdly, activities can be disclosed, for example officially through a sustainability report, a greenhouse gas emissions protocol, etc. Fourthly, certification can take place. This involves introducing and improving certificates and standards, such as various ISO standards or other eco-labels, which help to reduce emissions.34 More information can also be found in the chapter “Communication and Reporting”.

The last category includes carbon capture & compensation. Carbon capture involves the technology-based and natural capture of greenhouse gases, e.g. through carbon capture and storage or residue management strategies. In addition, trading with emission credits can take place. This is possible by participating in trading with EU allowances or other certificates and by utilising the Kyoto mechanisms. Finally, offsetting can also be practised. However, this should only be done if emissions cannot be reduced any further. Offsetting can also be used to improve existing standards.34

The two authors Lewandowski and Ullrich (2023) also assessed the frequency of use, and the perceived effectiveness of the emission reduction measures based on a survey of 65 companies. According to their findings, energy acquisition, carbon capture, self-regulation, clean fuel, energy recovery and HR sustainability measures are among the most effective measures for reducing corporate greenhouse gas emissions. While only 18% of the companies surveyed use carbon capture, the figure for HR sustainability measures is 80%. For companies to achieve net zero emissions as efficiently as possible, they should start with the most effective measures.34

4 Drivers and Barriers

This chapter presents the drivers and barriers for achieving net zero emissions within companies. Companies are influenced by both external and internal drivers to reach net zero targets. Additionally, there are external and internal barriers that hinder companies from achieving net zero goals. This section will continue with an analysis of external drivers and barriers, followed by internal drivers and barriers.

4.1 External Drivers

There are several external drivers that motivate companies to reduce GHG emissions and increase their net zero commitments:

1. The urgency of addressing climate risk and meeting the Paris Agreement goals.

The international community has increasingly influenced corporate decision-making in achieving net zero emissions. The Paris Agreement goals have been internalized by governments, regions, cities, and companies, leading them to align themselves to achieve the targets. Energy companies like Shell, BP, and Total announced in 2020 their commitments to become net zero in accordance with the Paris Agreement goals. Experts have declared the necessity of taking measures to prevent climate change, which directly impacts companies due to extreme weather events. This influence extends to investors, insurers, and lenders who are also connected to the companies.19

2. External from stakeholders including investors, competitors and costumers.

In 2019, according to the annual report of Climate Action 100+, the initiative influenced several companies, including Nestlé, Duke Energy, and Maersk, to commit to net zero emissions. By 2020, additional companies, including Shell, were also influenced by Climate Action 100+ to make similar commitments. Investors and reinsurers are increasingly assessing the risks of climate change due to the growing losses they face from more frequent and severe natural disasters. SwissRE, one of the largest insurance and reinsurance companies in the world, is no longer providing insurance or reinsurance to companies with more than 30% exposure to thermal coal utilities. They are focusing on companies that are oriented and prepared for a low carbon economy and have long-term net zero targets.19

3. Competitors pressure

Companies also face pressure from competitors. When one company sets net zero targets, it encourages industry peers to establish their own net zero targets. Thus, companies, in their pursuit of climate leadership, may increase their ambitions or accelerate the timing of their climate goals. This is advantageous for companies that are first movers, as they can become climate leaders. This means that the more companies publish net zero targets, the more other companies are ready to follow suit.19 The costs of important climate solutions is fast declining. Nowadays, the green options for the climate are frequently less expensive than the alternatives. Markets are opening up and expanding rapidly for sustainable energy systems, transportation solutions, agriculture, buildings, finance, and industry.35

4. Legislation and regulatory act

Setting policies, formulating environmental laws, clear commitment goals and building regulations are seen as a key driver to enhance Net zero building but they can be seen also as key drivers to implement net zero in the companies. Regulator and legislation framework are used to reduce uncertainty and regulations and standards to promote sustainability and net zero.36 In the EU, the creation of the Net Zero Industry Act (2023) stems from the Green Deal and aims to support the development of green technology within the EU. This means providing support for new technologies that produce low carbon, zero emissions, or negative emissions in their operations. It will create a market with easier access to clean technology in Europe and increase Europe’s competitiveness by creating many new high-quality jobs.37The Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD/CS3D), which became law in the EU in 2024, will require companies to address the human rights and environmental impacts of their actions both within and outside the EU. This directive is aligned with the Paris Agreement’s goal of achieving climate neutrality by 2050, meaning it will compel companies to develop plans for implementing net zero.38

4.2 External Barriers

Many policies for implementing net zero are imperative for corporates and highlight the changes that need to occur, starting with supply chains, stakeholders, communities, and industrial bodies, ensuring implementation happens within a specified timeframe. Some countries have taken measures to align with the 2050 net zero target, while others have yet to establish clear policies regarding net zero.39

The absence of detailed plans and distinct routes to reach the goal of net zero emissions by 2050 has led to criticism of the Paris Agreement policies. The development of clear policies has significant positive impacts, whereas their absence affects the achievement of targets in corporations, leading to issues in investment returns, technology innovation, and the adoption of green practices. This discrepancy impacts the international competitiveness of corporations, as those in countries with clearer policies can be more advanced and have a competitive advantage.40

Corporations also face external barriers over which they have little influence. An example is the conflict between Ukraine and Russia (2022), which has impacted corporations striving to commit to net zero targets. These barriers range from supply chain issues, where materials are no longer sustainable, to technological challenges that make it difficult for companies to maintain their commitment to net zero.39

The social-cultural barrier of public acceptance influences how open people are to adopting a new net zero option and how willing they are to change their behaviour to support it. Public acceptance also acts as a driver, such as the support for solar panel energy. According to a study by One Earth, there is a significant barrier in public acceptance of electric vehicles, highlighting the need for further studies to address and eliminate this barrier.40

4.3 Internal Drivers

Technological innovations are a crucial driver for the development of sustainable supply chains. Advances in information technology and knowledge management significantly contribute to optimizing business operations while simultaneously reducing CO2 emissions. The use of big data and machine learning, for instance, enhances efficiency in production processes and supports decision-making regarding sustainable practices. By analyzing large datasets, companies can implement targeted measures to use resources more efficiently and minimize emissions. Another significant driver is the internal corporate motivation towards environmental sustainability. Many companies are increasingly recognizing the necessity of making their supply chains more sustainable. This shift is driven not only by ethical considerations or compliance with legal requirements but also by economic considerations. Sustainable practices can help reduce environmental impacts and simultaneously improve corporate image. An environmentally conscious image enhances customer trust and can lead to increased customer loyalty, which, in the long term, has positive economic effects. Furthermore, regulation and political support play a crucial role in promoting sustainable business practices. Governments establish frameworks that encourage companies to adhere to environmentally friendly standards.41

4.4 Internal Barriers

One of the greatest challenges in implementing net zero practices is the high initial investment and ongoing costs associated with adopting sustainable technologies and processes. Many companies hesitate to make these investments because they do not see an immediate financial return. The uncertainty about the payback period for such investments and the long-term economic benefits of sustainable practices further contribute to this reluctance. Another barrier is the lack of knowledge and awareness about sustainable practices and technologies, both at the management and employee levels. Often, there is insufficient expertise to implement the necessary changes and effectively manage sustainable initiatives. This knowledge gap can lead to uncertainty and hesitation in adopting sustainability strategies, as companies may be unsure which measures will have the greatest impact and how best to integrate them into their existing operations. Moreover, there is often resistance to change, particularly in companies that have heavily invested in traditional supply chain models. These companies might resist the necessary adjustments, especially when these changes are perceived as disruptive and threaten existing business models. This resistance can occur at both organizational and individual levels, as employees and managers may fear that new practices will disrupt established workflows and create uncertainty regarding their roles and responsibilities. Overall, the high costs and investments, lack of knowledge and awareness, and resistance to change represent significant barriers that hinder progress toward a sustainable and emissions-free economy.41

References

1. UNFCCC. Paris Agreement. (2015).

2. Allen, M.R., et al. Net Zero: Science, Origins, and Implications. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 47, 849-887 (2022).

3. Fankhauser, S., et al. The meaning of net zero and how to get it right. Nature Climate Change 12, 15-21 (2021).

4. Conway, E. & Kamal, Y. Steps on the Journey to Net Zero. in Achieving Net Zero (Developments in Corporate Governance and Responsibility, Vol. 20) (ed. Crowther, D.a.S., S.) 3-24 (Emerald Publishing Limited, Leeds, 2023).

5. Rogelj, J., Geden, O., Cowie, A. & Reisinger, A. Net-zero emissions targets are vague: three ways to fix. Nature591, 365-368 (2021).

6. Loveday, J.M., G.M.; & Martin, D.A. Identifying Knowledge and Process Gaps from a Systematic Literature Review of Net-Zero Definitions. Sustainability 14, 3057 (2022).

7. Green, J.F. & Reyes, R.S. The history of net zero: can we move from concepts to practice? (2023).

8. UNITED NATIONS. UNITED NATIONS FRAMEWORK CONVENTION ON CLIMATE CHANGE. (1992).

9. UNITED NATIONS. Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. (ed. Parties, C.O.T.) (1997).

10. UNFCCC. CDM: About CDM. (n.d.).

11. UNITED NATIONS. KYOTO PROTOCOL TO THE UNITED NATIONS FRAMEWORK CONVENTION ON CLIMATE CHANGE. (1998).

12. UNFCCC. Fact sheet: The Kyoto Protocol. (2011).

13. UNITED NATIONS. All About the NDCs. (n.d.).

14. Van Coppenolle, H., Blondeel, M. & Van de Graaf, T. Reframing the climate debate: The origins and diffusion of net zero pledges. Global Policy 14, 48-60 (2023).

15. IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts

of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways,

in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development,

and efforts to eradicate poverty. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, (2018).

16. United Nations Environment Programme. What you need to know about the COP26 UN Climate Change Conference. (n.d.).

17. Allan, J., et al. Earth Negotiations Bulletin. Vol. 12 (2021).

18. Koonce, K. The Race to Net Zero: How ESG Investors Are Driving Corporations to Ethically Lower Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Environs: Environmental Law and Policy Journal 46, 111-134 (2023).

19. Erb, T., Perciasepe, B., Radulovic, V. & Niland, M. Corporate Climate Commitments: The Trend Towards Net Zero. (ed. AG, S.N.S.) (2022).

20. Hans, F., Kuramochi, T., Black, R., Hale, T., Lang, J., Mooldijk, S., Beuerle, J., Höhne, N., Chalkley, P., Smith, S., Hyslop, C., Hsu, A., Yeo, Z. Y., Hyslop, C., Yeo, Z. Y., Hale, T., Smith, S. & Axelsson, K. NET ZERO STOCKTAKE 2022. (ed. 2022, N.Z.S.) (2022).

21. Science Based Targets Initiative. step-by-step-process. (2024).

22. UNITED NATIONS. Net-zero commitments must be backed by credible action. (2024).

23. UNFCCC. Microsoft: Carbon Negative Goal | Global. (2023).

24. SWITCH Network. Measuring Progress: Key Performance Indicators for Tracking Net Zero Goals in Manufacturing. (2024).

25. §42 EnWG. (Germany, 2011).

26. Umweltbundesamt. Erneuerbare Energien in Zahlen. (2024).

27. Ifo-Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung. Energieintensive Industrie unter Druck. (Ifo-Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung, München).

28. WRI. Calculation Tools and Guidance. (2023).

29. PWC. Die Lösung zum Messen all Ihrer Emissionsdaten. (2022).

30. B Lab – B Cooperation. SDG Action Manager. (2024).

31. University of Oxford. Net Zero Climate. (2024).

32. Microsoft Inc. Supplier Corporate Social Responsibility commitments. (2022).

33. Science Based Targets Initiative. SBTi Corporate Net-Zero Standard. 1.2(2024).

34. Lewandowski, S. & Ullrich, A. Measures to reduce corporate GHG emissions: A review-based taxonomy and survey-based cluster analysis of their application and perceived effectiveness. J Environ Manage 325, 116437 (2023).

35. Exponential Business. The 1.5°C Business Playbook, (2020).

36. Ohene, E., Chan, A.P.C., Darko, A. & Nani, G. Navigating toward net zero by 2050: Drivers, barriers, and strategies for net

zero carbon buildings in an emerging market. Elsevier Ltd 242(2023).

37. European Commission. Net-Zero Industry Act. (n.d.).

38. European Commission. Corporate sustainability due diligence. (n.d.).

39. Gangadhari, R.K., Karadayi‐Usta, S. & Lim, W.M. Breaking barriers toward a net‐zero economy. Natural Resources Forum (2023).

40. Steg, L., et al. A method to identify barriers to and enablers of implementing climate change mitigation options. One Earth 5, 1216-1227 (2022).

41. Singh, J., Pandey, K.K., Kumar, A., Naz, F. & Luthra, S. Drivers, barriers and practices of net zero economy: An exploratory knowledge based supply chain multi-stakeholder perspective framework. Oper Manage Res 16, 1059-1090 (2023).