Author: Anna Bertram, October 20, 2024

1 Introduction

The business of business is no longer just business. It’s also about society, stakeholders, and sustainability.1 This statement illustrates the change that companies have to face in the modern economy. The main focus of a company’s business is no longer about making a profit. Today, social responsibility, sustainability and dealing with various interest groups, the so-called stakeholders, play a central role. The success of a company is no longer measured solely by financial figures, but also by how well it fulfills its social responsibility. But what happens if a company ignores the needs and expectations of its stakeholders? The Volkswagen (VW) diesel scandal shows the negative consequences this can have. VW had manipulated emissions values, which had a negative impact on its stakeholders.2 It shows how manipulation and unethical behavior can lead to a serious loss of trust, high penalties and severe reputational damage. The example makes clear how crucial it is to consider the interests of stakeholders and incorporate them into the corporate strategy. Stakeholder management is important at a time when the focus is increasingly on sustainability and social responsibility. Companies that actively engage with their stakeholders can better explain their actions and build trust.

This bachelor thesis shows why stakeholder management is an important tool for companies today. The motivation behind it is to better understand how companies work with their stakeholders and how these relationships influence long-term success. Good stakeholder management helps companies to become more resilient and respond better to external challenges. By engaging with different stakeholder groups, companies can develop innovative ideas, create new products and improve their processes. This often leads to a competitive advantage. Long-term success depends on how well a company understands its stakeholders and involves them in decision-making. Good relationships with stakeholders are therefore crucial. Stakeholder management is not just a theoretical consideration but has real implications in practice. Companies that actively involve their stakeholders can prevent crises and create stable long-term value.

2 The historical development of stakeholder management

Stakeholder management has a long and varied history and did not develop in a straight line to its current form. Freeman’s work is particularly significant, as he brought together and further developed the various precursors in a book on strategic management in 2010.3 The relevance of stakeholders was recognized even before Freeman. Adam Smith, a well-known economic theorist, demonstrated the understanding of economics and ethics in his work “The Theory of Moral Sentiments” and emphasized that individual morality and mutual interests are decisive for scientific action.4

Freeman divided stakeholder management into areas such as corporate planning, systems theory, corporate social responsibility and organizational theory, in which the concept of stakeholder management already existed. These areas are not linear, but are closely interlinked, which means that they influence and develop each other. The term “stakeholder” was first used in management literature in 1963 in a paper by the Standford Research Institute. This term was intended to show that shareholders are not the only group to which management must respond. The Stanford Research Institute (SRI) researchers argued that managers need to understand the demands and concerns of stakeholder groups in order to formulate corporate goals that ensure the necessary support for the company’s continued existence.3

2.1 Corporate planning

Ansoff rejected the stakeholder theory, which states that corporate goals should be based on balancing the interests of different stakeholders. He argued that goals should be divided into “economic” and “social”, with the economic taking priority. He saw stakeholders as a “dominant coalition” whose support depends on situational factors and is not always guaranteed.

In the 1970s, however, the stakeholder concept was increasingly taken up in strategic planning. It was assumed that the importance of shareholders would diminish and that companies should work more in the interests of stakeholders. Analyses from this period showed that managers often had different views of their stakeholders and that a thorough analysis could help to improve decision-making.

The stakeholder concept was used in this phase to gather information about important external groups such as employees, suppliers and consumers. As the business environment was relatively stable in the 1950s to 1970s, planning relied heavily on forecasting. However, there was limited attention paid to the external environment, which was predominantly viewed from an economic perspective. The application of the stakeholder concept was limited to the collection of general information about traditional stakeholder groups.3 5

2.2 System theory

In the mid-1970s, systems theory researchers including Russel Ackoff took up the concept of stakeholder analysis again. Ackoff built on Ansoff’s arguments and developed a method for analyzing organizations from a systems theory perspective. He saw companies as open systems and argued that social problems could be solved by transforming basic institutions and through the cooperation of the stakeholders involved. Instead of looking at problems in isolation, Ackoff emphasized the need for a synthesis in which the concerns of all stakeholders are included, and solutions are developed together.3

In this context, the term “collective strategy” became popular. It was no longer just about individual corporate strategies, but about how companies and stakeholders could work together on the future of the organization. There were two approaches: The first emphasized joint planning between companies and stakeholders, while the second focused on collaboration between a select group of stakeholders to work on specific problems.5

The systems theory model emphasizes broad participation and has been particularly useful in formulating complex problems. However, it focuses less on specific management strategies, which are important for the practice of strategic management, but more on the general design and function of systems.3

2.3 Corporate social responsibility

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has spawned many concepts and approaches that have brought about both short and long-term changes in companies. In the 1960s and 1970s, social movements such as civil rights, anti-war politics, environmental protection and women’s rights led to a change in the perception of the role of companies in society. Prominent economists such as Friedman and Galbraith argued in different directions about corporate social responsibility.3

A central feature of the CSR literature is the application of the stakeholder concept to non-traditional stakeholder groups, such as the public or local communities, which are often seen as critical of companies. Unlike traditional approaches, which focus on the satisfaction of owners, CSR literature places greater emphasis on social and environmental aspects.6

The stakeholder concept has been expanded in the context of CSR to include unconventional interest groups that influence a company’s economic and social performance. This expansion is intended to encourage companies not only to pursue profit maximization, but also to take responsibility for their social and ecological impact.5

However, one problem with previous CSR discussions was that they often looked at social and economic issues in isolation, without taking their interactions into account. As a result, these issues have not been sufficiently integrated at both management and intellectual levels. While the literature on corporate social responsibility has emphasized social and political issues, it has often neglected how these can be strategically embedded in the business system.3

2.4 Organizational theory

In the 1960s, the stakeholder concept was only further developed by a few organizational theorists who were primarily concerned with the relationship between companies and their environment. While many of these theorists did not explicitly use the term “stakeholder”, they nevertheless made important contributions to the understanding of these relationships. One of these researchers, Rhenman, defined stakeholders as individuals or groups who depend on the company to achieve their personal goals and on whom the company also depends. Stakeholders included employees, owners, customers and suppliers.

Rhenman’s definition differs slightly from the original stakeholder concept of the SRI, as he defined the term more narrowly. He argued that stakeholders are groups that have mutual claims on the company. He thus excluded groups that are only unilaterally dependent on the organization, such as government agencies or opposing groups. However, this narrow definition neglected important interest groups that, despite their influence on the company, did not have the same dependencies.

In recent decades, however, organizational theory has developed a broader focus that also extends to internal issues such as culture, power and politics in companies. This research has deepened the understanding of the dynamic relationships between companies and their internal and external stakeholders and offers valuable approaches for strategic management.3

2.5 Stakeholder management today

Stakeholder management has become increasingly important over the last two decades. This is reflected in the professionalization and introduction of standards that support companies in systematically shaping their relationships with stakeholders. An important milestone was the publication of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 26000 standard in 2010, which provides guidelines on the social responsibility of organizations and regards stakeholder management as a central component.7 8 At the same time, the Global Reporting Standards (GRI) have enabled companies to report more transparently on their economic, social and environmental impacts by promoting dialog with their stakeholders.9

3 The basics of stakeholder management

3.1 Definition and differentiation

An internal memo from the Stanford Research Institute in 1963 was a decisive turning point. In this document, the term “stakeholder” was introduced and defined for the first time. “Stakeholders are those groups without whose support the organization would cease to exist.”3 The term “stakeholder” is made up of the words “stockholder” and “stake”.10 The word “stake” has various meanings and can mean “share”, “influence”, “participation” or “support”, among others.11 This definition forms the basis for today’s understanding of the stakeholder concept and has been further developed and adapted over time.

Despite the numerous definitions that can be found in the specialist literature, the basic understanding of the term “stakeholder” has remained largely unchanged. The term can be interpreted in different ways. A narrower definition encompasses those groups whose support is vital for the survival of a company. This view emphasizes that companies, regardless of their size, must create value for these crucial groups, with the focus usually being on economic aspects. In this narrow definition, only those stakeholders are considered who either have a direct influence on the company’s sales and capital growth or whose absence could jeopardize these. Such definitions restrict the term “stakeholder” to groups that are of direct importance to the company.12 13

A broad definition of the term “stakeholder” encompasses all groups that can influence the company in some way and calls on managers to take these groups into account in order to create the greatest possible value.14 This broader perspective goes beyond purely economic aspects and considers both individuals and groups as stakeholders who are either affected by the company or can influence it themselves. In this broad definition, all persons and groups that have any kind of influence on the company or are influenced by its activities are therefore considered stakeholders. Only those who have neither power over the company nor are affected by its objectives are excluded.13R. Edward Freeman, who is considered one of the main thinkers behind the stakeholder concept, defines stakeholders as any group or individual who can influence the goals of an organization or who is affected by the achievement of these goals.3 This definition emphasizes the reciprocal relationship between a company and its stakeholders and highlights the fact that stakeholders can both influence the company and be directly or indirectly affected by its activities and decisions. A stakeholder is therefore any person, group or institution that has a claim on the company, be it through economic, social or ethical interests. This definition makes it clear that stakeholders are part of a complex network of interactions that is crucial to the long-term success and survival of a company.15

There is also a distinction between influence-based and legitimacy-based stakeholder definitions. Influence-based definitions include all individuals, groups or organizations that either influence the activities of a company or can be influenced by them. However, this perspective brings with it the challenge that the interests of the genuinely important stakeholders may be neglected due to the large number of stakeholders. In contrast, legitimacy-based definitions only recognize as stakeholders those who have a legitimate claim on the company. This claim can be based on ownership rights, participation in the value creation process, risk exposure or moral rights.16

The wide variety of definitional approaches clearly shows that no uniform definition of the term stakeholder has yet been established in the specialist literature. Despite these different perspectives, however, the fundamental core of stakeholder management remains largely unchanged. The success and continued existence of a company depends largely on how well it succeeds in taking into account and harmonizing the interests of the various stakeholder groups. R. Edward Freeman’s definition, which is recognized as central and comprehensive, emphasizes the reciprocal relationships between a company and its stakeholders.12

This paper is based on Freeman’s broader definition. This definition makes it possible to consider all relevant stakeholder groups. By applying this broad definition, the diverse interests and needs of stakeholders can be adequately considered in the company’s decision-making processes.

3.2 Changing corporate perspectives

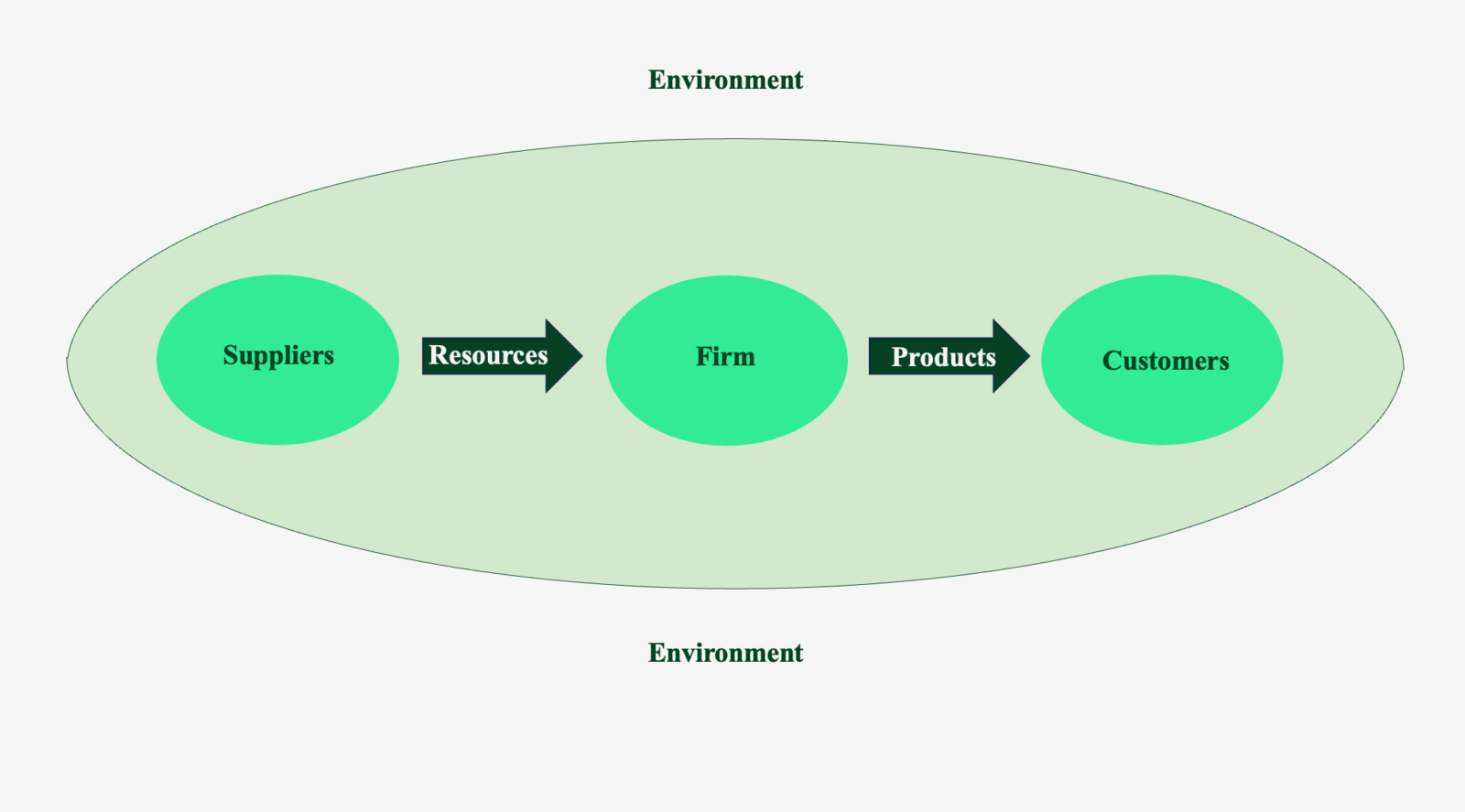

In the past, managing companies according to the principles of stakeholder management was relatively simple. The idea was that the flow of information between suppliers, the company and the market was rather one-sided. Essentially, the tasks consisted of procuring raw materials from suppliers, processing them in production and delivering the finished products to the customer. Figure 1 shows this simple production perspective, also known as the “production view of the firm”, in which the success of the company depended on satisfying both customers and suppliers. Most of the companies were purely family businesses that generally did not employ external workers.3

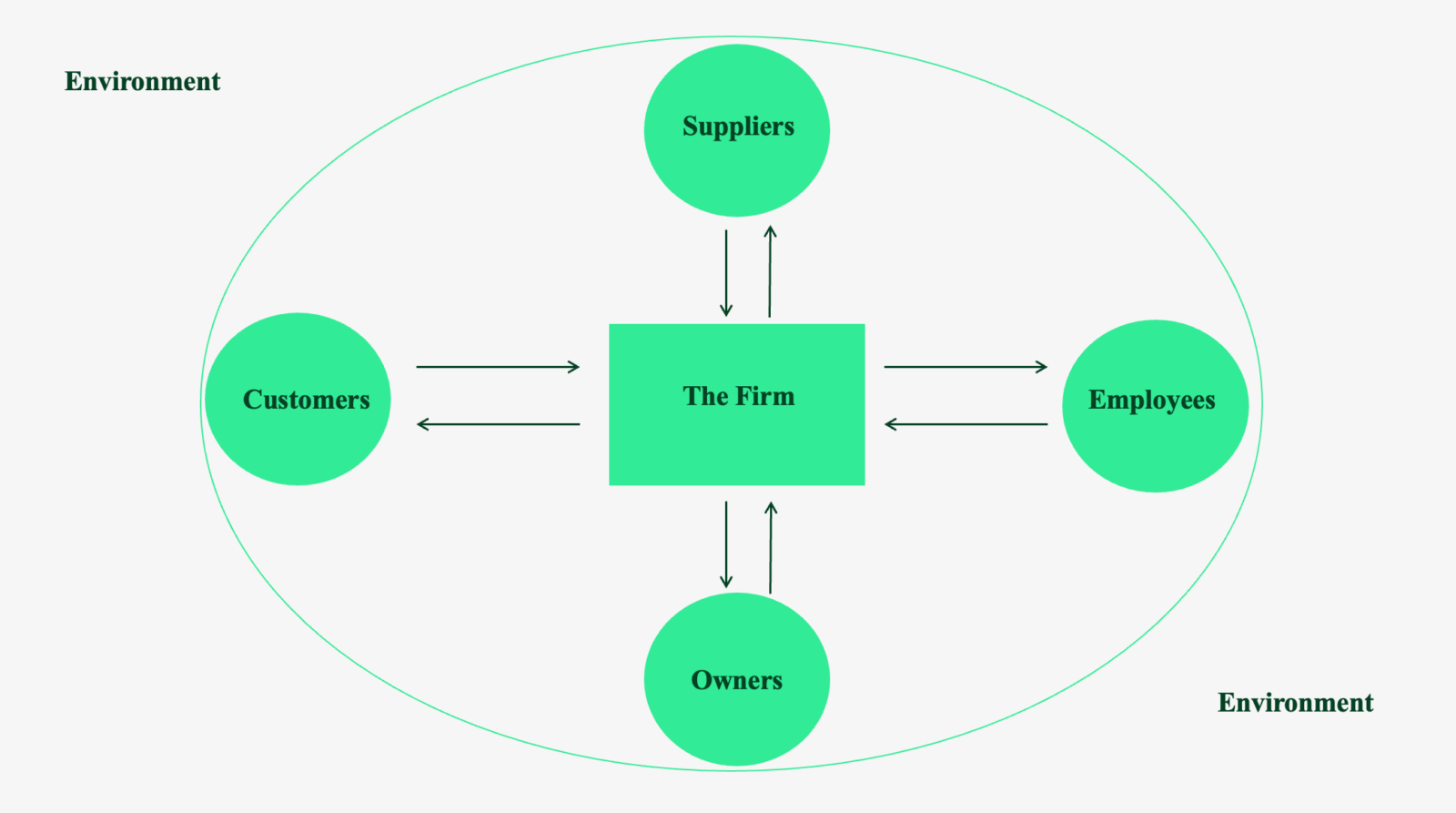

With industrialization and the accompanying changes such as the introduction of assembly line production, companies began to grow considerably. New technologies and energy sources became increasingly available and demographic developments encouraged production in urban areas. In addition, social and political circumstances required ever larger amounts of capital. Instead of pure family businesses, external labor increasingly took an important place in the companies. Figure 2 shows the resulting changes, in particular the increasing separation of ownership and control, which is referred to as the “managerial view”. With the involvement of banks and shareholders, who contributed to the financing of the companies, ownership shifted away from the founders. To remain successful and goal-oriented, managers had to consider the interests of owners, employees and their unions, suppliers and customers at the same time.3

3.3 Basic idea of stakeholder management

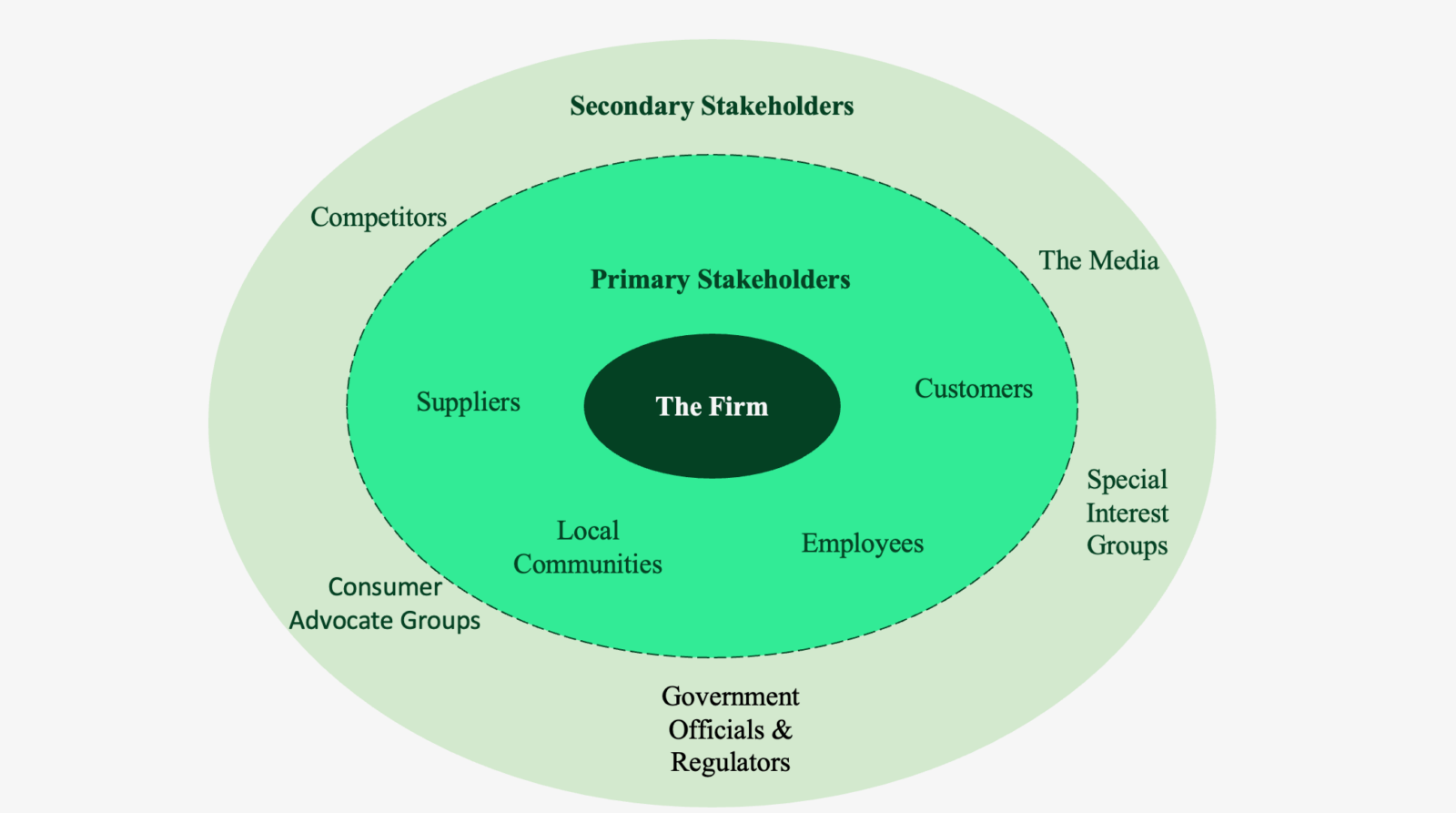

Stakeholder management has changed significantly over time, particularly due to increasing international competition and the growing number of interest groups that companies have to take into account. In order to meet these new requirements, a revised approach is needed. Figure 3 shows what modern stakeholder management looks like by illustrating the various interest groups of a company and their importance and relationship to the company. It is first important to clarify what is meant by “(the) firm” in this context. Here, the term “firm” is used to describe a structure that organizes and manages the resources and activities of stakeholders. The aim is to create added value, which is then distributed fairly among the stakeholders.17

The diagram shows a company in the center, surrounded by the primary stakeholders in the inner circle. These are surrounded by the secondary stakeholders who form the outer ring. These groups are closely linked to the company and are interdependent. The long-term success and survival of the company depends heavily on how well it succeeds in meeting the needs of these stakeholders. This is why managers should pay particular attention to these groups.14 It is important to understand that the distinction between primary and secondary stakeholders is not always clear-cut.18 The boundaries between these groups are often blurred and permeable, which is symbolized by dashed lines in diagrams. This means that a stakeholder can be considered both primary and secondary, depending on the situation or perspective.17

The primary stakeholders include customers, suppliers, employees and communities. This group is directly involved in the company’s value creation processes and makes a significant contribution to its success. Their influence is not only of an economic nature; they can also derive emotional satisfaction, security, respect, political voice, knowledge or valuable network connections from their relationship with the company.17 This interdependence means that the company is also dependent on these stakeholders. They often have a strong influence on company decisions, and it is crucial to achieve their satisfaction.19 When it comes to the primary stakeholders, the company cannot survive without their continued support. Should one of them become dissatisfied and withdraw partially or completely, this could have serious consequences for the company, even to the point of jeopardizing its existence. For example, community dissatisfaction may lead to activists asking the government for support, which could lead to stricter regulations that threaten the company. It is therefore crucial for the sustainable growth and survival of a company that the needs and expectations of its primary stakeholders are met.17

The outer circle of the diagram shows the secondary stakeholders, which include groups such as the government, media, competitors, consumer rights organizations and special interest groups. Although these groups have no direct claims on the company, they can nevertheless exert a great deal of influence. They affect the company’s ability to achieve its goals and are also influenced by the company. Each of these groups has the power to change relationships with the primary stakeholders. Secondary stakeholders are generally not directly involved in the value-creating processes of a company but have a legitimate interest in its activities. Their impact can either help or hinder the company’s ability to create value. Many companies are therefore now entering into partnerships with these stakeholders aiming at a better management of their influence. Competitors are a special type of secondary stakeholder, as their decisions and actions can have a direct impact on the success and achievement of the company’s goals.17 This group is also not directly decisive for the company’s survival but can steer public opinion in a direction that is either advantageous or disadvantageous for the company.19

Stakeholders are also people who do not only act rationally, but also emotionally. They bring their own experiences, cognitive abilities, perspectives and backgrounds that shape their expectations and behavior. This diversity of characteristics makes it necessary for the company to precisely understand the individual characteristics and motivations of stakeholders. Only then can management respond effectively to the various demands and maintain positive relationships.17 It is also important to recognize that stakeholder roles can change over time. A secondary stakeholder could become a primary stakeholder in certain circumstances as their influence on the organization grows or as their needs and expectations come to the fore. It is therefore essential to continuously monitor and respond flexibly to these changes in order to manage stakeholder relationships effectively and run the business successfully.3

Almost every company has some form of contact with funders, customers, suppliers, employees and the community. These groups are essential and should be considered fundamental. Especially in the early stages of a business, no one group is often more important than another. In a newly founded company, for example, there are sometimes no fixed suppliers yet, which is why the focus is often on a few customers or other important stakeholders.3 Internal and external changes can also play a major role. Internal changes refer to adjustments that take place within the company. Executives or management must regularly review their goals and policies to meet the changing demands of customers, employees, shareholders and suppliers. Such changes usually take place within a known framework and follow established rules. External changes, on the other hand, are caused by external factors such as the emergence of new groups, events or issues that may be difficult to fit into the existing corporate model. These external changes can bring uncertainty and often require a fundamental revision of the corporate strategy.20

3.4 Aspects of stakeholder theory

Stakeholder theory can be viewed from three different perspectives, each of which sheds light on different aspects of a company. These three perspectives are closely interlinked.

One of the perspectives of stakeholder theory is the descriptive view, which claims that the stakeholder model best reflects the actual processes in companies. This theory is used to describe specific characteristics and behaviors of companies. For example, stakeholder theory helps to understand the foundation of the company, how managers think about governance, how board members consider the interests of different groups and how some companies are run.21 The descriptive perspective accurately depicts the operational reality. Since legal and social requirements, such as labor and environmental laws or co-determination regulations, oblige management to consider the interests of stakeholders anyway, this model is considered particularly appropriate. It offers an alternative view of what constitutes a company by describing companies as an interplay of cooperative and competing interests. Furthermore, it is argued that the stakeholder approach is particularly well suited to reflect the diverse and complex environment in which modern companies operate today.22

The risks of using only descriptive data, such as legal facts, to support a theory are well known. The problem with this is the so-called “naturalistic miss”. This means that a valuation is made without the necessary analysis of the company’s business, i.e. conclusions are drawn from the “actual” and “target”. Another problem is the danger of making hasty generalizations. If one relies only on descriptive data, the theory could become useless if new studies show that managers are turning away from a stakeholder orientation. However, this observation shows that the theory is more than just a description. Even if legal or societal trends change, few supporters are likely to abandon the theory completely. This suggests that the descriptive arguments for stakeholder theory in the descriptive perspective, as well as the criticism of it, are only of limited importance.21

The second perspective in stakeholder management is the instrumental perspective, which focuses on typical corporate goals such as profit, competitiveness, innovation and growth.22 This perspective follows the principle: “We should do it because it will pay off in the end.”23 The idea behind this is that good stakeholder management can help to achieve these goals. The management of relationships with stakeholders should therefore have a positive impact on the success of the company. However, it is difficult to prove this assumption unequivocally. The question arises as to what exactly is meant by stakeholder management and how success should be measured. Even if the direct connection between stakeholder management and corporate success cannot always be clearly proven, there are nevertheless theoretical reasons that make this connection appear plausible.22 In research, the instrumental perspective is often used to examine possible links between stakeholder management and traditional corporate goals such as profit and growth. Many studies that deal with corporate social responsibility and take the stakeholder perspective into account use statistical methods or are based on observation and interviews. Regardless of the method, these studies often show that the consideration of stakeholder interests contributes just as well or even better to the achievement of corporate goals than other approaches.21

Unsurprisingly, not all stakeholder theory can be fully justified by instrumental perspectives. The available data is often insufficient and, while the analytical arguments are valuable, they are ultimately based on more than purely practical reasons. The significance of this finding is that even if the stakeholder approach were as effective as other approaches, few would abandon it. The economic outcomes of stakeholder management and conventional management were found to be similar. Nevertheless, it was emphasized that the moral aspects are crucial, and stakeholder analysis is seen as an essential part of business ethics.21

The last perspective is the normative approach. This approach is based on the assumption that all stakeholders have a right to be respected and are not merely a means to an end. This means that all stakeholders’ interests should be considered equal, regardless of their influence on a company’s financial results. The normative perspective argues that the stakeholder model is better than other corporate approaches for moral reasons. Even if no positive influence on economic goals is identified, it is assumed that management has a responsibility to protect the company as a whole. It should not favor only one stakeholder group, as this could jeopardize the stability of the entire system. The task of management is to make decisions that are in the best interests of all stakeholders, balancing conflicts of interest as best as possible.22 This approach provides a basis for interpreting the role of companies and provides moral or philosophical guidelines for their management. Normative considerations have been central to stakeholder theory from the outset and remain an important component today. Even critics such as Friedman, who argued against corporate social responsibility, rely on normative considerations to justify their views.21

Stakeholder theory can be viewed from three different perspectives, each of which offers its own value for understanding the relationships between companies and their stakeholders. The descriptive aspect of the theory describes how companies interact with their stakeholders. It explains existing relationships and provides a basis for analyzing and predicting corporate behavior in the future. This perspective is particularly helpful in understanding the reality of companies and their stakeholder management. In contrast to the instrumental approach, it establishes a link between stakeholder management and traditional corporate goals such as profitability. It argues that good stakeholder management can contribute to achieving economic success. However, the exact link between stakeholder management and corporate success often remains vague and is rarely examined in detail. The normative approach focuses on what companies should do based on ethical and moral actions. It makes categorical, rather than hypothetical, recommendations and assumes that stakeholder management is important because it is morally right. In much of the literature, both proponents and critics, the normative view is strongly represented, even if the underlying moral principles are often not examined in detail.21

Freeman also emphasizes that no matter what goals are pursued, the impact of one’s actions on others and their potential impact on the company must be considered. This requires an understanding of the behaviors, values and backgrounds of the groups involved, including the social context. To be successful in the long term, it is important to have a clear answer to the question: “What do we stand for?”24

4 The strategic importance and impact of stakeholder management on the company’s success

A simple example illustrates why a stakeholder approach is so important for companies. Steve Jobs, the founder of Apple, used the introduction of iTunes and the iPod to meet the needs of multiple stakeholders.25 With this strategy, he offered consumers a legal alternative to music piracy and managed to combine the interests of various stakeholders such as consumers, the music industry and developers.

This example shows how crucial a broad stakeholder perspective can be for the long-term success of a company. Research, including Freeman’s, shows that companies must actively engage their stakeholders in order to successfully create value. This involves companies not only utilizing the resources of their stakeholders, but also the information and insights they provide. This collaboration enables companies to develop new approaches that increase value for all stakeholders. When companies work closely with their stakeholders, they can not only share important information but also identify trends at an early stage. This allows them to develop value-adding strategies that help the company remain competitive and successful in the long term.

Innovation plays a central role in a company’s value creation. It is not only about new products and services, but also about new organizational and technological processes that are developed and implemented. Viewing an innovation from the perspective of several stakeholders enables companies to better identify both internal and external interest groups and to take their needs and expectations more into account. This promotes acceptance when new products, services or processes are brought to market. Particularly when introducing new products and services, success depends to a large extent on the information provided by customers. This not only allows potential conflicts to be identified at an early stage, but also enables targeted improvements to be made to ensure stakeholder acceptance. In addition, such an approach makes it easier to adapt innovations to market needs and requirements, which significantly increases the chances of success. Companies that work closely with their stakeholders cannot only promote innovation, but also ensure that it is supported and accepted by a wide range of stakeholders. This contributes to a stronger market position and sustainable success in the long term.

Globally active companies are often faced with the challenge of interacting with a large number of different and often interdependent stakeholders. In this complex environment, the stakeholder approach not only helps companies to identify relevant stakeholders, but also to develop the necessary skills to deal successfully with this diversity. A common problem is the strong focus on shareholders. Management tends to focus on the conflict between the interests of shareholders and other stakeholders. However, a stakeholder approach helps to resolve this conflict by developing strategies that create value for both shareholders and other stakeholders. These value-creating strategies are inclusive and consider all relevant stakeholders rather than focusing on just one group. This enables management to take better account of the concerns and influences of different groups, which strengthens the company’s efficiency and adaptability in the long term.17

5 Stakeholder analysis

There comes a time in every company when managers have to decide how to deal with the interests and demands of the various stakeholders. These decisions have a significant impact on the future development of the company. It may also become necessary to adjust stakeholder strategies voluntarily or under pressure in order to meet the expectations of stakeholders. By taking the needs and expectations of the relevant stakeholders into account, a company can promote sustainable success and long-term growth, whether by introducing a comprehensive management concept or by adapting the corporate culture.3

For the purpose of developing the right strategy for a company, stakeholder analysis usually involves four key steps.26First, all relevant stakeholders are identified in order to find out which groups or individuals are influenced by the company or can influence it. In the second step, these stakeholders are examined more closely by analyzing them according to certain criteria and dividing them into groups to better assess their possible behaviors. In the third phase, concrete measures are implemented based on the findings. Finally, in the fourth phase, suitable communication strategies are developed to ensure a regular exchange with the stakeholders. It is crucial that this process is continuously reviewed and, if necessary, repeated consequently remaining able to react flexibly to changes. It may also be necessary to revise individual steps or restart the entire process.22

Before the first step of the stakeholder analysis is carried out, the company’s mission must be clearly defined.27 A well-formulated corporate mission provides information about why the company exists and what goals it wants to achieve. However, there is often disagreement about how a company’s core business is defined. A clear mission answers fundamental questions about the corporate identity and provides orientation. It summarizes the company’s values, goals, culture and overall purpose.28 Such discussions are positive as long as they are conducted openly and constructively and lead to a better understanding.27

5.1 Identification of stakeholders

The first step to determine the relevant stakeholders in a company, is to identify the stakeholders. The identification and categorization of stakeholders depends on how the term “stakeholder” is defined, as the definition often influences the identification process. The aim here is to determine which groups or individuals are considered stakeholders.29 The exact composition of these stakeholders can vary depending on the definition chosen by the company. As already explained in section 4.1, a narrower definition focusing on capital utilization only takes into account those stakeholders who have a direct influence on the company’s capital growth or who could jeopardize it. A broader definition, on the other hand, refers not only to the economic aspects, but also considers all people and groups as stakeholders who are influenced by the company or who can influence the company.13 14

In addition to identifying stakeholders, there are various perspectives that can be adopted. This can be done from an inside-out or outside-in perspective. The inside-out perspective looks at stakeholders from the inside out and categorizes them based on different criteria and characteristics. In contrast, the outside-in perspective takes the stakeholders’ point of view and looks at the company from their perspective.22

From the inside-out perspective, stakeholders can be divided into primary and secondary groups. As already explained in section 4.3, primary stakeholders are of central importance for the survival of the company and often have legal claims against the company. Secondary stakeholders, on the other hand, are not directly related to the company’s activities, but are affected by them and can influence the company indirectly through their influence on primary stakeholders. The media and various interest groups are considered secondary stakeholders in this definition, as they are able to shape public opinion about a company’s performance.19 As primary stakeholders are directly linked to the company’s activities, they are assigned greater importance than secondary stakeholders.16 Freeman also refers to this prioritization indirectly at first, but explicitly later on.5 The distinction is not based on a special legitimacy of primary stakeholders, but on their greater power, as they are crucial for the survival of the company.16

The outside-in perspective focuses on analyzing the external environment of a company in order to identify relevant stakeholders. Methods such as the PESTEL analysis or a social issue analysis can be helpful in determining the right stakeholders.22

Regardless of which definition or perspective a company ultimately chooses, an initial rough classification of stakeholders can be made. An affinity diagram could be used here as a tool to structure information and bring order to a multitude of ideas that arise in a brainstorming session, for example. After collecting potential stakeholders in a brainstorming session, you start to create an affinity diagram by grouping similar or related stakeholders. The diagram then serves as a visual basis for further analysis and planning.30 Figure 4 illustrates a concrete example of how stakeholder identification could look using an affinity diagram. In this diagram, the potential stakeholders are divided into different categories in order to determine which stakeholders the company is in contact with.

There are various tools that can be used to structure and identify stakeholders. The affinity diagram is one method, but there are also alternative tools that offer similar benefits. Table 1 shows further options for structuring and identifying stakeholders.30

Table 1: Tools for Structuring and Identifying Stakeholders

| Tool name | Definition |

| Tree diagram | The tree diagram makes it possible to break down a problem into smaller sub-areas and analyze which sub-problems are associated with which stakeholders. It provides a systematic overview of the stakeholders and their potential influence on the company. |

| Arrow diagram | The arrow diagram, also known as the activity network diagram, supports the analysis of the sequence of stakeholders and can help with identification. It shows which stakeholders need to be monitored in particular. |

5.2 Basics of stakeholder analysis

5.2.1 Stakeholder mapping

Once the company has identified its stakeholders, it is crucial to classify these stakeholders based on clear characteristics.22 Not every identified stakeholder has the same influence on the company. Therefore, the company should investigate what interests the stakeholders have, how willing they are to actively engage and at what point in time they would like to do so.31 The goals that a stakeholder pursues influence both their behavior and their relationship with the company. Often the goals of different stakeholders, even within the same stakeholder group, are contradictory and cannot be met simultaneously, which can lead to significant conflict. For example, some employees may want to work more to improve their status, while others may want a better work-life balance. Similarly, there are customers who are waiting for more favorable offers, while other customers want to receive their product as quickly as possible. In general, these different stakeholder interests can be divided into the following types:

- Material interests

- Political interests

- Social interests

- Informational interests

- Spiritual interests22

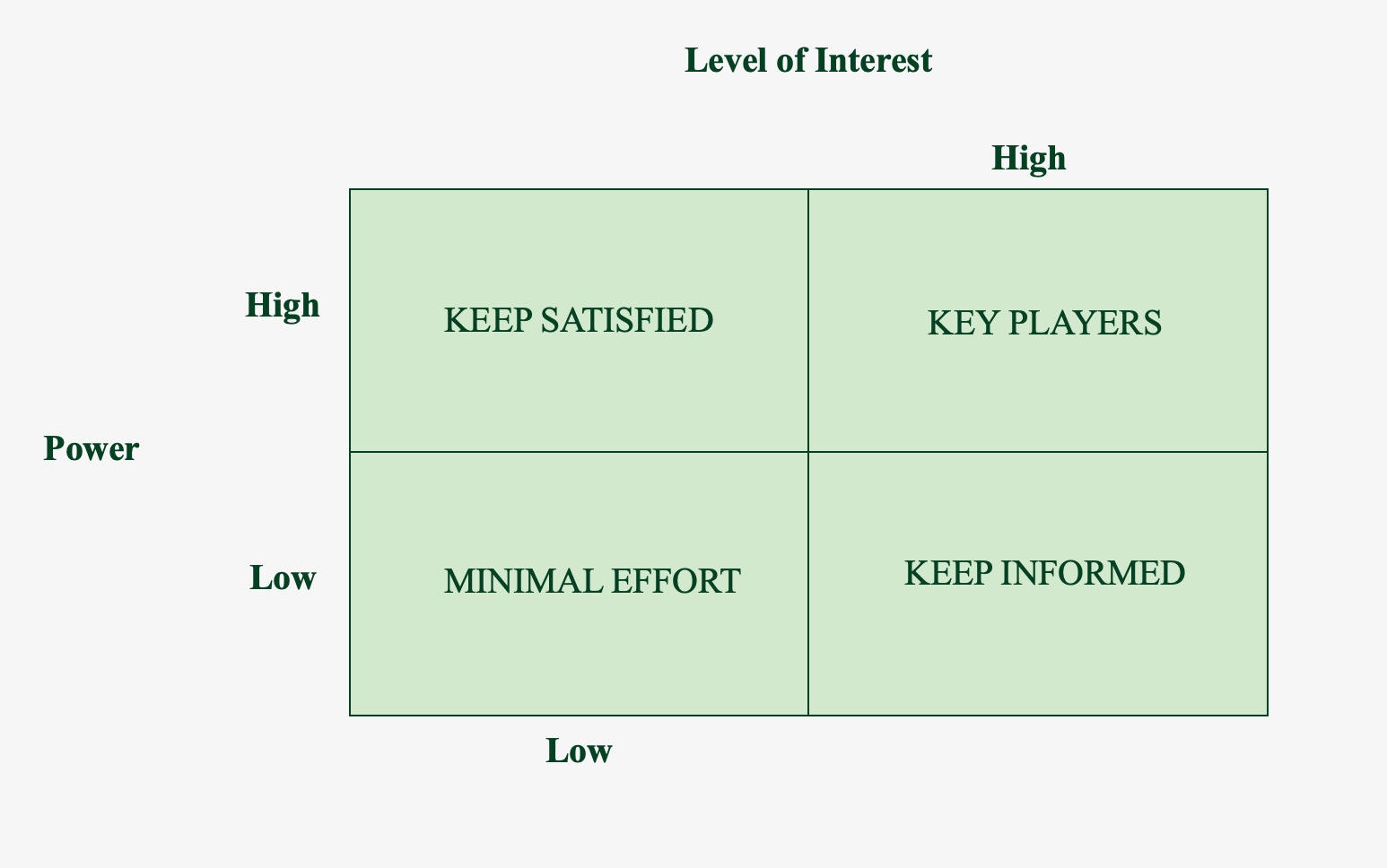

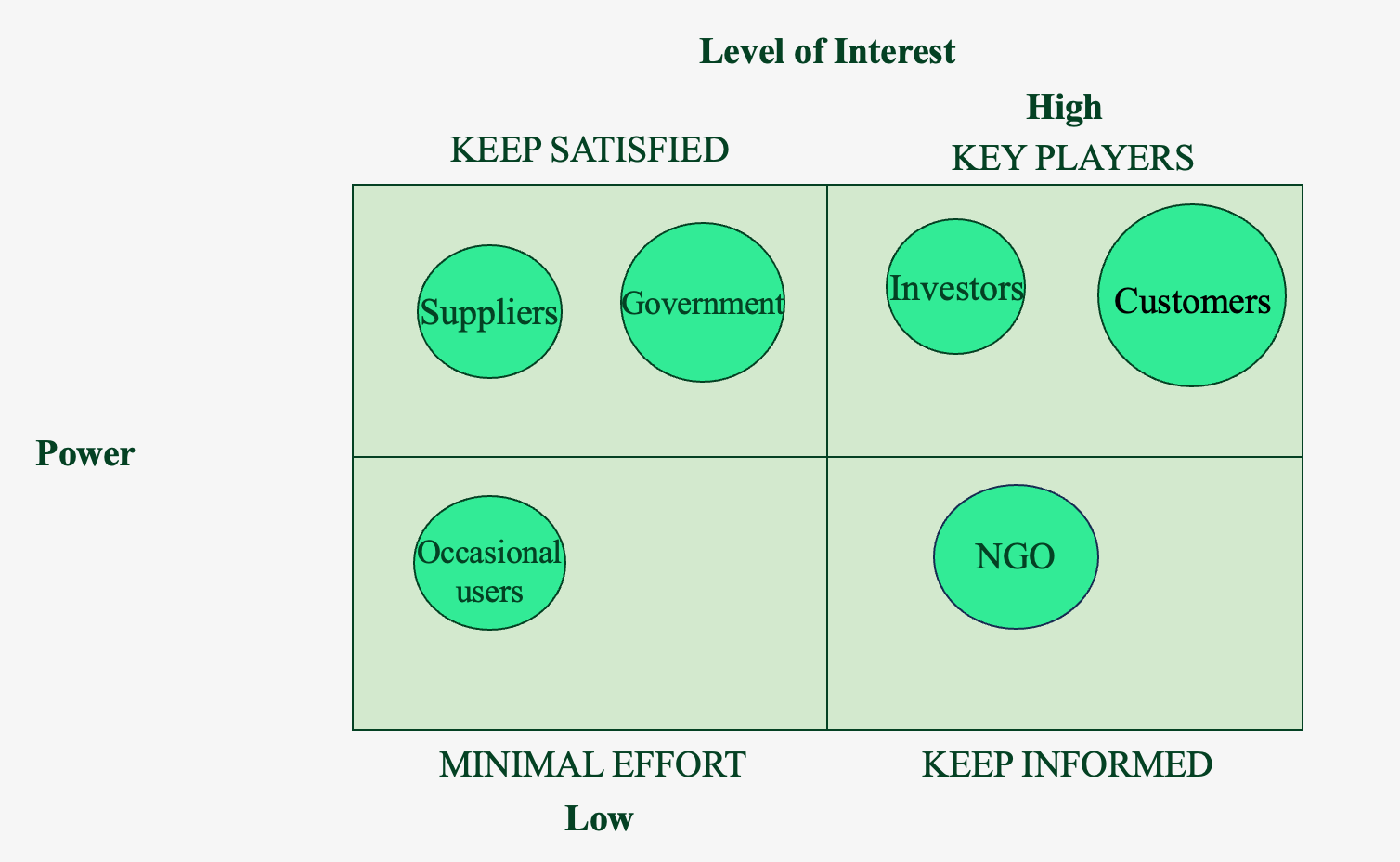

In order to obtain a comprehensive overview of the stakeholders and their position, it is useful to create a so-called stakeholder matrix based on Mendelow’s original model. A stakeholder matrix can be created quickly and easily by comparing the “interest” and “influence” axes in a 2×2 matrix. This analysis results in four categories of stakeholders, each of which requires a different priority for the company, which can be seen in Figure 5.32

Strong power/high interest: These stakeholders, also known as key players, are characterized by a great deal of power as well as a strong interest in the company. This means that management must involve them closely and ensure that their needs and expectations are taken into account. It is important to work closely with them to ensure that their influence is used positively, and their concerns are met. As these stakeholders are very interested in the company and have a positive attitude, they are crucial to supporting the company.33 They act as “ambassadors” and can convince other stakeholders and gain their approval. Therefore, the company must ensure that they remain interested and are not distracted by other issues.31 It is also important to involve them in important decisions, as their input is valuable, and their support is crucial to the success of the company. On the other hand, stakeholder interest can also be negative if they work against the company’s goals and want to prevent certain outcomes. Their power can be so strong that they seriously affect the company’s activities and successes.34 Nevertheless, they are the most important group in the stakeholder matrix and must be carefully managed and involved. The company must clearly explain its objectives and procedures to them so that their concerns and special requirements can be considered. This group usually includes executives, major investors or important customers.35

Strong power/low interest: These stakeholders, also known as Keep Satisfied, have a lot of power but are currently not very interested in the company’s progress. It is important that the company clearly communicates its goals and benefits to them without overwhelming them with too many details. Although they do not need regular and detailed updates, they should be informed about important progress and achievements and be involved in key decisions.33 As these stakeholders have considerable power, they are important to the company. Care must be taken to ensure that they recognize the benefits of the company, even if their interest is currently low. Their influence could become relevant at any time, which is why the company should keep an eye on them. If these stakeholders are negative, there is a risk that they could jeopardize the project. However, if they are positive, it is important to arouse their interest and win them over as supporters of the company.35

Low power/high interest: These stakeholders are called Keep Informed, they are very interested in the company but have less influence. It is important to keep them regularly informed and use their interest positively to support the company. They can act as valuable ambassadors or advocates for the project inside and outside the company.35 These stakeholders should be kept up to date and actively involved. A sense of responsibility and belonging can be created through targeted information and participation. If they have a negative attitude towards the company, they may not cause serious damage due to their limited influence, but they can still cause unrest and potentially cause delays by spreading negative sentiment. Examples of stakeholders in this group are employees, local communities or specialized customer segments.33

Low power/low interest: These stakeholders, also known as minimal effort, have neither significant influence nor great interest in the company. It is therefore not necessary to devote much attention to them as part of stakeholder management.35 It is advisable to keep an eye on this group, but not to devote significant resources to them. The company should nevertheless be prepared in case their interest or influence changes in the future. Examples of this group could be external partners or other less involved groups.33 It makes sense to inform them about the company and its potential impact without going to great lengths to do so. If the company nevertheless decides to involve them more, similar considerations apply to them as for the Keep Informed.22

5.2.2 Stakeholder forecasting

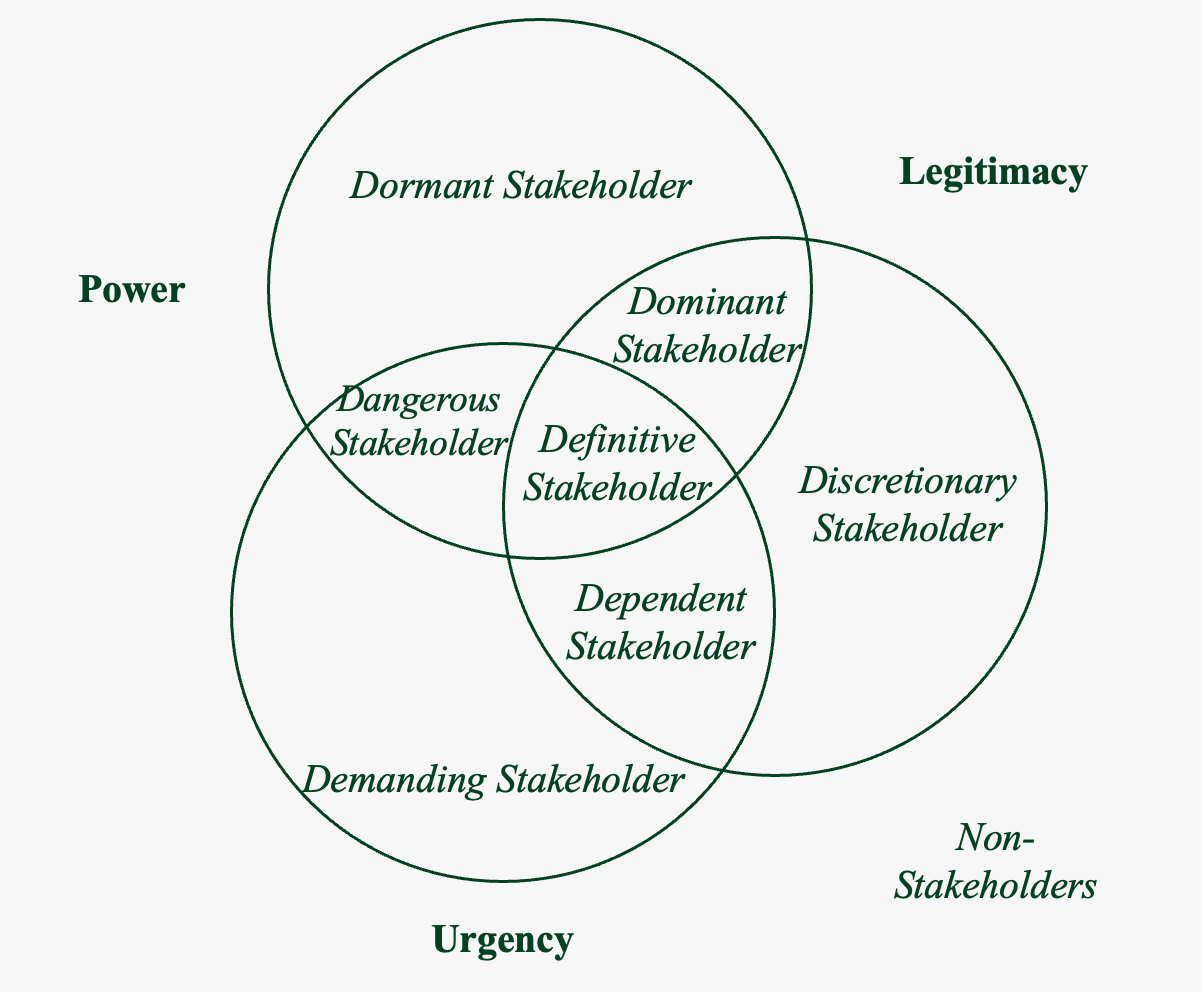

Stakeholder forecasting is an additional step to stakeholder analysis in which an attempt is made to predict the development and speed of stakeholder concerns.22 A model developed by Mitchell et al. in 1997 combines three important characteristics: Power, legitimacy and urgency. This combination leads to a categorization into seven different stakeholder types, which enables companies to systematically analyse their environment. This model represents a detailed and comprehensive method for assessing stakeholders by expanding the common definitions and adding the characteristic “urgency”.12 Each stakeholder is characterized by these three attributes. It is important to understand that these characteristics can change over time and are socially constructed, meaning that they do not necessarily reflect objective facts. Stakeholders may or may not be aware of these characteristics and in this respect, they have a choice as to whether they wish to use them towards the company. Stakeholders who do not have any of these three characteristics – power, legitimacy or urgency – are classified as “non-stakeholders”.16 Depending on the combination of these characteristics, it helps managers to prioritize and manage stakeholder relationships in a targeted manner. The more characteristics a stakeholder group has, the more important it is for the company and the more attention should be paid to it. Mitchell et al.’s model does not suggest that managers should pay equal attention to all stakeholder groups. Instead, depending on specific goals and perceptions, managers should pay attention to certain stakeholders in different ways. In this way, the model enables a flexible and situation-dependent prioritization of stakeholders.12

Power: Stakeholders have different levels of power that they can use to assert their interests against a company. Power means being able to persuade another person or group to do something that they would not otherwise do.16 Pfeffer describes this definition as a “relationship between social actors in which one person A persuades another person B to do something that B would not have done without this influence.” According to Weber, power is also the “probability that someone in a social relationship can assert their own will, even if there is resistance.” Ultimately, power is difficult to define but clearly evident when it is exercised.12

Legitimacy: Stakeholders have different expectations of a company. Mitchell uses a broad concept of legitimacy that encompasses various foundations such as morality, ownership or contracts. What is important here is how management perceives this legitimacy.16 It also examines whether the company is the right contact for the concerns of stakeholders and whether the public interest is affected. Suchman[1] describes legitimacy as the general view that the actions of an organization are considered appropriate and acceptable in a social system of norms and values.36 Legitimacy is a socially recognized good that goes beyond one’s own perspective and can be understood and negotiated differently depending on the context.12

Urgency: Stakeholders also differ in terms of the demands they make of a company. Urgency has two aspects. Firstly, time criticality – i.e. how unacceptable it is for the stakeholder if management delays a response to their request or relationship. Secondly, the importance – i.e. how important this demand or relationship is for the stakeholder.16 If a request is urgent and a delay would be unacceptable for the stakeholder, the urgency is high. The importance of the requirement also plays a role: the more important it is for the stakeholder, the more urgent it is. The inclusion of urgency in stakeholder theory helps to understand what priorities management must set and how to respond to different stakeholders. So far, power and legitimacy have taken center stage, but urgency complements the model. Urgency can arise for a variety of reasons, such as when a stakeholder owns company-specific assets that are difficult to replace, when there is an emotional attachment such as long-term ownership of shares in a family, when there is an expectation that the company will continue to provide valuable services, or when the stakeholder perceives risks in the relationship with the company.12

The Figure 6 shows three overlapping circles that show the characteristics of power, legitimacy and urgency. Different categories of stakeholders emerge at the intersections of these circles. The overlaps make it clear that some stakeholders have more than one characteristic, which increases their importance and influence on the organization. This shows how complex the network of relationships between the organization and its stakeholders is, with the various combinations of characteristics determining the dynamics and priority of the relationships.12

There are a total of seven different types of stakeholders; if you include non-stakeholders, there are eight types, as you can see in Figure 6. If none of the three main characteristics – power, legitimacy or urgency – apply to a stakeholder, it is classified as a non-stakeholder. Stakeholders who have all three characteristics are decisive. Such stakeholders are referred to as “definitive” because management perceives them as influential. These could include stock corporations or major shareholders, for example. Stakeholders who have both power and legitimacy are already part of a company’s dominant group. If the demands also become urgent, it is clear to management that they must give this demand the highest priority. It often happens that a dominant stakeholder moves into the category of definitive stakeholder.

There are three other groups of stakeholders, each of which has only two of the three key characteristics. One of these is the dangerous stakeholder. This group has power and urgency, but no legitimacy. Therefore, they could be considered a threat to the company, as they may act coercively or even violently. The second group are the dominant stakeholders. These stakeholders have both power and legitimacy and therefore exert a secure influence on the company. They therefore form a dominant coalition, as their legitimate claims on the company are recognized and enforceable. However, they may either assert their claims or refrain from doing so, depending on their decision. The last group comprises the dependent stakeholders. Although these stakeholders have legitimate and urgent claims, they lack the power to enforce them independently. They are dependent on other stakeholders or management giving them the necessary support to assert their claims. Classically, this could include employees and staff.

There are also three other groups of stakeholders for whom only one of the characteristics applies. These stakeholders are generally less important to the company, as management only recognizes one characteristic in them. On the one hand, there are the dormant stakeholders. Their only characteristic is power, which theoretically gives them the ability to impose their will on the company. However, since they have no legitimate relationship with the company and no pressing demands, their power remains dormant. Therefore, they have little to no interaction with the company. The discretionary stakeholders have the characteristic of legitimacy but have neither power nor urgency. This means that there is no pressure on management to actively engage with this group of stakeholders, although the company could choose to do so voluntarily. Finally, there are the demanding stakeholders whose only relevant characteristic is urgency. They may be annoying, but they are not a real threat. Their demands are not urgent enough to warrant more than cursory attention from managers. Unless these stakeholders can add another characteristic, their importance to the organization remains low.12

One advantage of this model is its clear structure, which enables stakeholders to be prioritized precisely by using power, legitimacy and urgency as criteria. This means that it can be used flexibly, regardless of the company’s current situation. In addition, resources can be invested specifically in important stakeholder relationships. One disadvantage is that stakeholder characteristics can change over time, whereas the Mitchell et al. model tends to remain static. It cannot fully reflect the dynamic changes in stakeholder relationships.37

5.3 Strategy implementation

The previous chapter explained how stakeholders can be identified and categorized. Building on this, stakeholder mapping was presented in detail. With this basis, targeted measures can now be developed that can be translated into effective communication strategies.

If we now look at Figure 7, we can see exactly four possible strategies that can be applied. Imagine that a company is planning the launch of a new product. In this case, customers and investors should be given intensive support. The strategy is to be in close contact with them and actively involve them in the decision-making processes. These stakeholder groups should receive the most attention from management, as the success of the new product depends heavily on whether these stakeholders feel involved and valued. If customers are involved early in the development process, potential problems can be identified and resolved before the product is launched. This involvement not only promotes satisfaction but can also increase customer loyalty as they feel that their opinions and needs are taken seriously.38 15

In contrast to investors, who have a high financial interest in the success of the new product. Their trust and support are often crucial for financing and resource allocation in the company. The involvement of investors can lead to them providing additional resources or activating valuable contacts and networks that can support the market success of the product. If both groups feel involved, they are less likely to use their influence against the company. Instead, they will use their resources and influence to create additional value together with the company. Therefore, dialog and negotiation should be encouraged to strengthen collaboration.15

Government authorities and suppliers both belong to the “Keep Satisfied” category. Although these stakeholders have a strong influence on the success of the company, they are less interested in the success of the product. Government authorities have a lot of power through legal requirements, even if they are not directly interested in the success of the product. The company must ensure that it complies with all laws and regulations to avoid penalties or production stoppages. It is important to provide regular reports and maintain contact with the authorities so as not to risk negative consequences that could also damage the company’s image. Suppliers who provide important materials for production also have a major influence. If there are delays or interruptions in deliveries, this can significantly affect the production process Even if they have less interest in the product, it is crucial that they remain reliable partners. Close cooperation can ensure that they support the company, for example through preferential deliveries.15

Non-governmental organizations (NGO) can be a good example of stakeholders with a high level of interest but little direct influence. These NGOs often have a vested interest in ensuring that new products are environmentally friendly but cannot force decisions within the company. However, they have the power to influence public opinion, and their support can help the company to build a positive image. To win these NGOs as supporters, the company should regularly provide them with information on how the new product protects the environment. Through reports or events, the company can show that it is pursuing sustainable goals. If NGOs feel that the company is responsive to their concerns, they could support the company by sharing their positive opinion with their followers. This strengthens the company’s image and could even help to attract more environmentally conscious customers.15

Occasional users or consumers have little to no interest in a new product as they are unlikely to buy or use it. They also have no influence on the company as they are not regular customers and therefore do not have a strong connection to the company. Therefore, little attention should be paid to them. Simple sources of information such as newsletters or general advertising are sufficient to possibly still arouse interest among these stakeholders. It is important to reach this type of stakeholder with minimal effort and few resources, without making major investments.15

5.4 Stakeholder governance

5.4.1 Definition

Once the stakeholder analysis has been completed, the focus should now be on stakeholder governance. This helps to clearly regulate how collaboration and communication with stakeholders will take place so that all plans and strategies can be implemented in a meaningful way. Governance means creating clear rules and structures in relationships in order to avoid conflicts. It defines who is allowed to make decisions, which actions are permitted or prohibited and how cooperation is to take place. This ensures that everyone involved knows what is expected of them and how information and responsibility are shared.

The scope of stakeholder governance can vary greatly. In some cases, there are close agreements with only a few stakeholders and a simple set of rules. In other cases, governance is much more complex, with numerous stakeholders and detailed agreements between them. The main aim is to encourage stakeholders to participate in and support sustainability projects. Unlike traditional governance models, which often only focus on the financial interests of the owners, stakeholder governance also takes into account social, environmental and ethical aspects of business activities. This promotes a comprehensive and sustainable approach to corporate governance.

Different types of contracts can provide a solution to create clear arrangements for stakeholder governance. Formal contracts often demonstrate that such governance structures benefit companies. Both formal and informal agreements help to clarify the needs and expectations of the parties involved. This enables joint action that creates benefits for both sides. Stakeholder governance mechanisms make it possible to negotiate across differences, find common ground and secure the commitment of all parties involved. In this way, long-term benefits can be achieved.39

However, this is not just about simple agreements, but about the management of much broader relationships between a company and its stakeholder groups. The focus here is on the creation and distribution of value between the groups involved. Freeman emphasizes that developing a theory of stakeholder governance that can reconcile both economic and non-economic stakeholder interests is a complex task.40

5.4.2 GRI standard

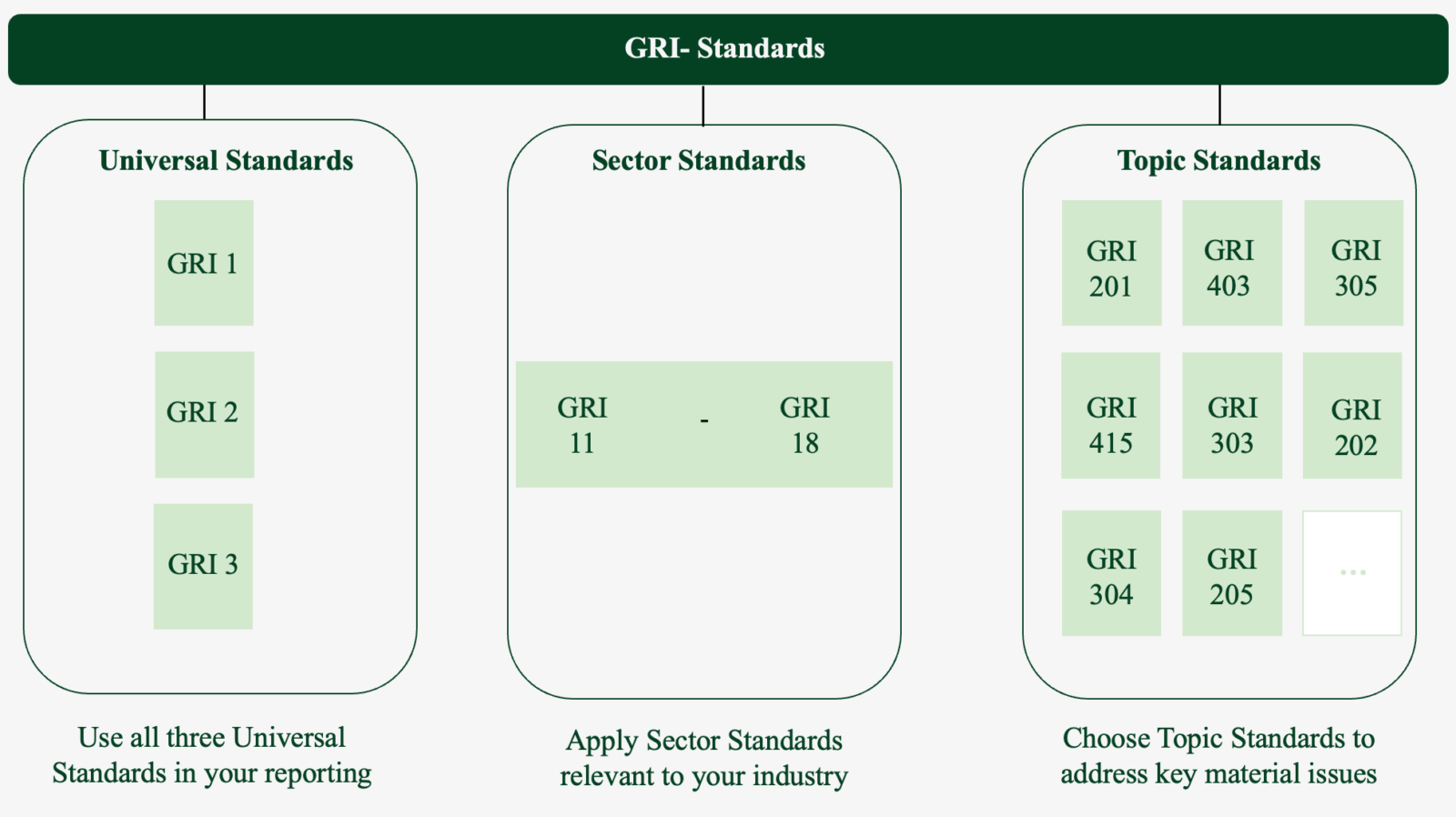

The GRI is a set of rules that forms part of stakeholder governance. It is an internationally recognized system that helps companies to present their sustainability performance in a structured and understandable way. With this framework, companies can clearly demonstrate their environmental, social and economic impact and illustrate their responsibility towards society and the environment. The report provides clear guidelines on how companies can disclose their sustainability efforts and make them transparent. The GRI standards are divided into three main categories.9

The GRI Universal Standards are generally applicable standards that can be used by any company. They consist of three main sections. GRI 1: Fundamentals 2021 This section explains the purpose of the GRI Standards and introduces important concepts that need to be considered when applying the Standards. It also sets out the requirements that a company must meet in order to report in accordance with the GRI Standards. Basic principles such as accuracy, balance and verifiability are essential to ensure reliable and comprehensible reporting. GRI 2: General Disclosures 2021 This is where basic information about a company’s structure and reporting practices is compiled. This includes details about activities, employees, management structures, strategies and stakeholder engagement. This information helps to better understand the profile of the company and the impact of its actions. GRI 3: Material topics 2021 This category describes how a company identifies the most important topics that affect its activities. It explains how the Sector Standards are integrated into this process and how to report on these material topics. This also includes how a company deals with the respective topics.

The GRI Sector Standards were developed to improve the quality and consistency of sustainability reports from various sectors. The aim is to develop standards for a total of 40 different sectors. Each Sector Standard begins with an overview of the key characteristics of the sector, including the activities and relationships that influence its impacts. The main section identifies and describes the key sustainability topics for each sector, including references to the appropriate GRI topic standards that organizations must use in their reporting.

The GRI topic standards cover specific sustainability topics, such as waste, occupational safety or taxes. Each standard explains the respective topic and contains specific requirements on how companies should deal with these topics. Companies select the relevant topic standards that match their material topics and use them to report on their sustainability performance.

Figure 8 provides an overview of the various standards in this context and shows where which information can be found.41

By applying GRI standards, companies can show their stakeholders that they act transparently and responsibly. This strengthens trust in the company. GRI reporting requires that stakeholder expectations are taken into account and shows how the company is responding to them. Although the GRI standards are voluntary, many companies use them to credibly present their sustainability efforts. A clear and transparent sustainability strategy based on the GRI Standards can also improve a company’s image and set it apart from its competitors.42

5.5 Stakeholder engagement

Stakeholder engagement describes the active process of involving stakeholders in decision-making and working together with them. As stakeholder engagement is the active part of stakeholder governance, it ensures that the interests and concerns of stakeholders are systematically integrated into corporate management. Engagement refers to both voluntary participation and the responsibility that companies have towards their stakeholders. It encompasses the methods and processes that companies use to engage with stakeholders and take their concerns into account. The aim of stakeholder engagement is to improve communication and gain the support of stakeholders for planned decisions or projects. It also helps stakeholders to better understand the company’s plans. Stakeholder engagement is about how companies respond to the needs and expectations of their stakeholders and whether they enter into a dialog in a respectful manner. A company must show that it takes stakeholder concerns seriously and strives to find solutions to minimize the negative consequences of its actions.43

The AccountAbility1000 (AA1000) Stakeholder Engagement Standard is a helpful tool for this. This internationally recognized standard provides companies with a clear structure for organizing dialogue with stakeholders. This ensures that the interests and concerns of stakeholders are taken into respected in a company’s decision-making process. This not only strengthens trust, but also supports responsible and sustainable corporate governance.44

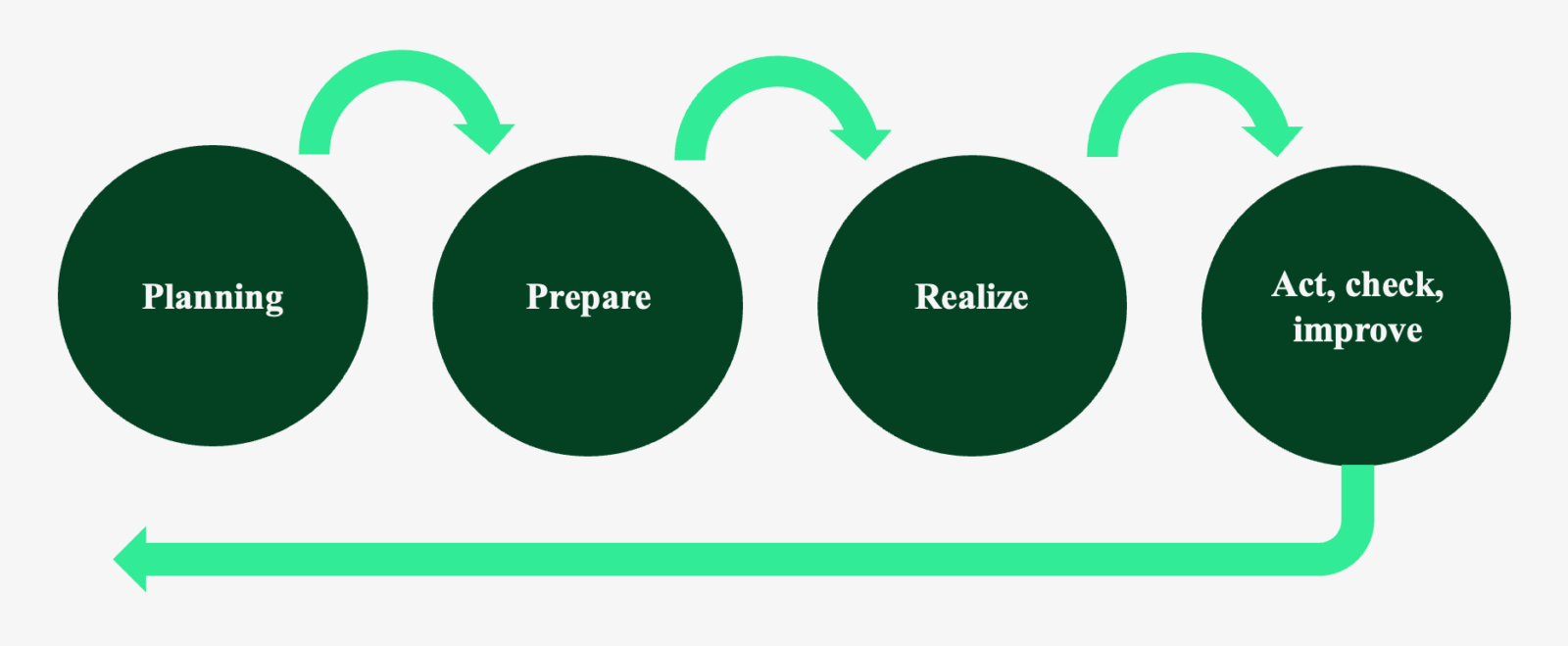

Figure 9 shows a typical stakeholder engagement process. This process begins with planning and preparation, during which all relevant stakeholders are identified, and the objectives are defined. This is followed by the actual implementation, in which the planned measures are carried out and the stakeholders are actively involved. After implementation, the company checks whether the set goals have been achieved. If there are any deviations or opportunities for improvement, the company should initiate measures to optimize the process. This is also a continuous process that starts all over again if the goal is not achieved.45

5.5.1 Stakeholder engagement plan

A stakeholder engagement plan helps to manage collaboration with various interest groups over the entire duration of a project. This tool serves as a strategic document and timeline that sets out clear activities and objectives for engaging with stakeholders. As not every stakeholder group can be approached in the same way, different approaches and communication tools are needed to successfully address each group. Particularly with important stakeholders, simple involvement is often not enough. An essential part of the plan is the selection of appropriate communication methods to ensure that the right channels are used to effectively reach each stakeholder group. To achieve this, all available means of communication should be listed to find out which are most suitable for each target group. Once the communication strategy has been determined, the company focuses on the detailed planning of individual activities to ensure communication with stakeholders and to meet their expectations.46

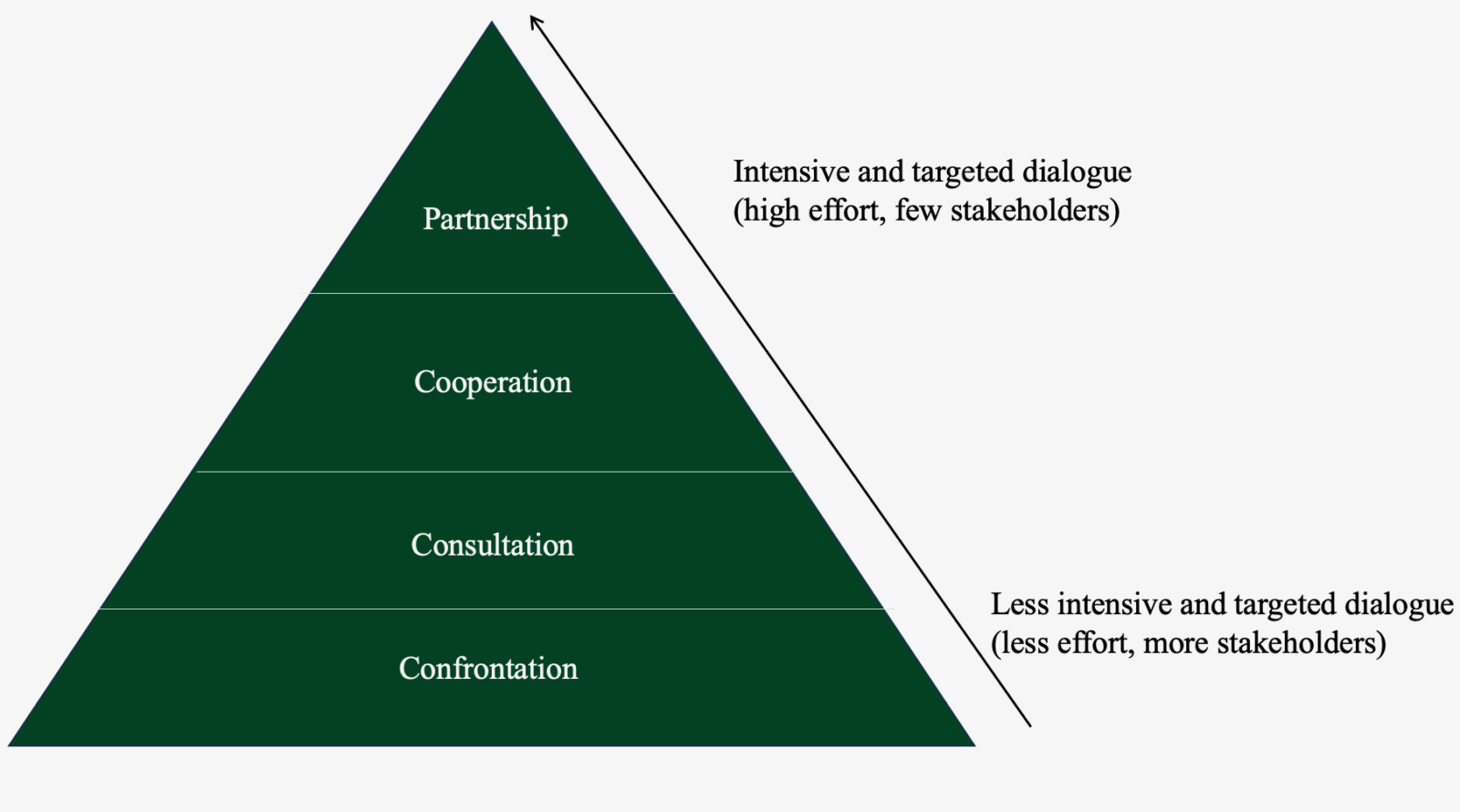

When a company’s focus is on short-term profits, stakeholder management is often defensive. This means that the company tries to avoid problems or only passes on partial information. Defensive strategies involve denying facts or rejecting responsibility. Selective information means that only a certain part of the reality is presented to the public or those affected, while important information that would be necessary for a comprehensive picture is withheld. Pure consultation encourages stakeholders to share their opinions, but it is up to management to decide whether these suggestions will be recognized. The company’s decision-making processes remain in the hands of management and are not democratized. This communication relies on internal and external channels, as shown in Figure 10. The higher up you go, the more intensive and specific the dialog with important stakeholders becomes, while the company conveys only general information at the bottom.22

5.5.2 Stakeholder dialog

Stakeholder dialogs enable companies and their interest groups to openly exchange opinions and expectations. The aim is to discuss interests together and develop guidelines for responsible action. This exchange helps the company to better understand its environment, while the stakeholders learn more about the challenges facing the company.22 Through dialog, companies go beyond simple negotiations to reach a deeper understanding. A well-managed stakeholder dialog not only strengthens the stakeholders’ identification with the results, but also promotes their commitment to implementation. Dialogue promotes transparency, protects and strengthens the company’s image, improves the flow of information and strengthens cooperation. It also allows potential conflicts to be identified and resolved at an early stage, which leads to better decisions. Such dialogues can take various forms and focus on both consultation and cooperation in implementation.45

There are two main types of stakeholder dialog, which differ in their focus. In stakeholder dialogs with a focus on consultation, the emphasis is on systematically collecting the opinions and interests of the various stakeholders and incorporating them into the decision-making process. These dialogs are often structured and designed to integrate different perspectives. In stakeholder dialog with a focus on cooperation and implementation, stakeholders work together to achieve a common goal. It is not just about exchanging opinions, but about actively working together to develop and implement solutions.45

Stakeholder dialogs with a focus on consultation differ from one-off and long-term consultations. One-off consultations provide an opportunity to gather opinions, raise awareness of a particular issue and arouse the interest of stakeholders for future collaboration. The aim is also to share experiences. The challenge lies in organizing events in such a way that not only information is passed on, but also the views of the participants are truly heard. Only if there is genuine interest in the different perspectives a constructive dialog can develop. Such consultations can take the form of conferences, workshops or meetings and usually last one to three days. Recurring stakeholder events, which can extend over one to two years, are suitable for longer-term consultations in which various interest groups are regularly involved. These regular meetings aim to achieve concrete results and enable a continuous exchange of ideas that focuses on specific issues.45

Stakeholder dialogs with a focus on cooperation can be initiatives and partnerships. Cooperative stakeholder initiatives work across sectors to tackle complex challenges and develop and implement joint strategies, approaches or sustainability standards.45 Stakeholders join such initiatives in order to achieve a common goal within a set period of time. Communication and negotiation techniques, contract design, relationship management and the motivation of those involved play a central role.22

Stakeholder partnerships can often involve time-limited projects where the focus is on the joint implementation of measures. In uncertain and complex environments, stakeholders are often interdependent. These dependencies require close collaboration in order to minimize risks and ensure joint success.23 Clear agreements and contractual obligations are required to ensure that collaboration runs smoothly. Larger budgets are often managed among the stakeholders involved, which requires professional project management as well as regular monitoring, control and evaluation procedures. These partnerships are under pressure to meet agreed targets and milestones on time and to regularly document progress. Each partner has a clearly defined role and is responsible for specific areas.45

The table 2 provides a clear overview of the typical phases of a stakeholder dialog. Each phase is named in detail and explains what needs to be done in that step. It also highlights the key communication aspects that should be considered during the process to make the dialog successful and effective.45

Table 2: Key Phases of a Successful Stakeholder Dialog: Process Overview and Communication Focus

| Goal | Communication | ||

| Step 1 | Exploration and integration | – Understanding the topic and concerns – Involving the field of action in dialog – Identify stakeholders | – Hold informal discussions to identify needs and urgencies – No public communication yet |

| Step 2 | Structure and formalization | – Set common goals – Planning resources – Strengthening relationships | – Open communication, involve all stakeholders – Create transparency – Build trust |

| Step 3 | Implementation and evaluation | – Implement agreed goals – Monitor progress | – Keep everyone involved in dialog |

| Step 4 | Further development and integration | – Continuing the dialog in the long term – Involve new stakeholders – Expand management structures | – Expand dialog – Adapt new goals and structures – Retain principles from the first phases |

A clear distinction between internal and external communication is of great importance in stakeholder dialog to ensure that information is exchanged effectively and in a targeted manner. Internal communication refers to the exchange of information between the parties and organizations directly involved in the stakeholder process. The focus here is on the direct stakeholders who actively participate in the dialog. External communication, on the other hand, is aimed at a wider audience or other relevant stakeholders who are not directly involved in the dialog but who are nevertheless interested in the process or could be affected by the results.45

The following table 3 provides a rough overview of the various communication channels that companies can use to get in touch with their stakeholders. However, it is important to note that each company must decide individually which channels are best suited to the respective stakeholders and situation. The choice of communication channels should be carefully considered to ensure that messages are effectively targeted.45 47

Table 3: Overview of Communication Channels for Engaging Stakeholders

| Communication channels | Type | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| E- Mail | Intern/Extern | – Direct and familiar method- Fast transmission to specific persons | – Limited interaction – Not ideal for building a community |

| Face-To- Face Meeting | Intern | – Strengthens relationships – Immediate feedback – Good for complex information | – Time consuming – Requires physical presence |

| Intranet | Intern | – Centralized source of information- Long-term communication possible | – Employees might not regularly use it |

| Instant Messaging | Intern | – Fast feedback | – Constant notifications can be overwhelming |

| Social media | Extern | – High visibility- Build relationships – Wide target group | – Requires careful management – Risk of negative public reactions |

| Press and public relations | Extern | – Formal communication – Ideal for official announcements | – Less interaction with the general public |

| Newsletter | Intern/Extern | – Regular updates – Simple distribution (digitally) | – Limited feedback – Often ignored if too frequent |

| Company website | Intern/Extern | – Detailed contents – Detailed explanation of topics – Promotes engagement | – Limited reach – Requires continuous content creation |

| Advertising | Extern | – Broad reach – Brand awareness | – High costs – Limited interaction (no direct interaction or feedback) |

| Service provider (e.g. call center, hotline) | Extern | – Direct contact with customers and their concerns | – Less control over quality control |

The rapid advances in information and communication technology have brought about such profound changes that they are often referred to as the “fourth industrial revolution”.14 As a result, modern communication technologies are becoming increasingly important as more and more people, regardless of their age, use digital channels.48 These new technologies, such as Instagram, TikTok and Twitter[2] 49, allow stakeholders to organize themselves more quickly and effectively. Millions of people can now easily connect with each other and develop common ideas. Companies therefore need to use new communication channels, as traditional methods such as newsletters are no longer sufficient.14 Older generations are also increasingly turning to technology, making it important to integrate digital platforms into stakeholder management.48 Today’s companies need to use dynamic, digital approaches to successfully engage with stakeholders and manage change effectively.14

6 Stakeholder monitoring

6.1 Continuous monitoring and adjustment

Once stakeholders have been involved in the stakeholder engagement process, it is crucial to continuously monitor and manage this process. The stakeholder engagement plan from section 6.5.1 forms a valuable basis for systematically tracking the planned measures. This ensures that the interests and expectations of stakeholders are regularly reviewed and adjusted. The interests or influence of stakeholders can change during the course of the pursuit of a company’s goal, which is why it is necessary to adapt the strategies flexibly. Monitoring plays a central role here. It is an ongoing process that regularly checks whether the objectives are being achieved and whether the strategies still correspond to the current circumstances.50

As monitoring can be both time-consuming and costly, it is important that sufficient financial and human resources are made available. This ensures that monitoring is carried out continuously to guarantee the long-term success of the project and ensure effective stakeholder involvement.51

6.2 Stakeholder database

A stakeholder database can be an extremely useful tool to facilitate the monitoring of stakeholder activities. It serves as a central point of contact for all relevant information on the individual stakeholders and can help to improve the strategic planning and control process. One of the key requirements of such a database is that the information stored must always be up to date. This requires regular updates to ensure that all changes in stakeholder relationships are taken into account. In addition, the stakeholder database supports the monitoring of interactions by recording when and how a stakeholder was contacted. This makes it easier to check the effectiveness of engagement measures. By recording feedback and reactions from stakeholders, the company can continuously evaluate the progress and success of its strategies.

In addition, the database enables the creation of reports and analyses that demonstrate to management or external partners how well stakeholders have been involved and to what extent their expectations have been met. This creates transparency and helps to build trust with stakeholders.22

7 Challenges and prospects in stakeholder management