Author: Christianna Angela Roth, November 24, 2024

1 Definition of Corporate social responsibility

Votaw posits that “the term [CSR] is a brilliant one; it means something, but not always the same thing, to everybody”8(p. 25). There is no universally accepted definition of the term CSR. The term CSR is used concurringly with a plethora of different terms in the finance, accounting, and management academic literature. Although the various terms associated with CSR may differ slightly in their academic connotations, they can all be subsumed under the umbrella of terms used to evaluate the company’s involvement in its corporate community.9 It can be argued that a clear definition of a concept, or at least its core underpinnings, is essential for understanding its essence. This is because it provides a foundation for meaningful empirical analyses and enables the construction of a robust theoretical framework.10 The complexity and multi-dimensional nature of CSR allow for a variety of definitions.11 The lack of an all-encompassing definition of CSR, coupled with the resulting diversity, and overlap of terminology, definitions, and conceptual models, hinders academic debate and ongoing research.12-15 A considerable number of studies have already examined the various definitions that have been proposed.10,16,17 The following table provides an overview of the most commonly used definitions in chronological order:

| Author | Year | CSR definition | Central research questions |

| Bowen | 1953 | “Social responsibility refers to the obligations of businessmen to pursue those policies, to make those decisions, or to follow those lines of action, which are desirable in terms of the objectives, and values of our society. Interest in politics, in the welfare of the community, in educations, in the ‘happiness’ of its employers, and, in fact, in the whole social world about it. Therefore, business must act justly as a proper citizen should”18 (p. 6). | What differentiates a reasonable and an unreasonable expectation of businessmen?How might businesses align their economic interest with their responsibilities as impartial and ethical citizens? |

| Sethi | 1975 | “Social responsibility implies bringing corporate behaviour up to a level where it is congruent with the prevailing social norms, values, and expectations of performance”19(p. 70). | What techniques does CSR employ to assess its influence on social norms, values, and expectations regarding performance? |

| Carroll | 1979 | “The social responsibility of business encompasses the economic, legal, ethical and discretionary expectations that society has of organisations at a given point in time”6 (p. 500). | What strategies might be employed to reconcile societal expectations with business responses?Does this indicate that businesses are exclusively reactive to societal expectations? |

| Drucker | 1984 | “The proper social responsibility of business is to tame the dragon, that is to turn a social problem into economic opportunity and economic benefit, into productive capacity, into human competence, into well-paid jobs, into wealth”20 (p. 62). | Which methodology might be applied to ascertain the non-economic benefits? |

| Wood | 1991 | “The basic idea of [CSR] is that business and society are interwoven rather than distinct entities; therefore, society has certain expectations for appropriate business behaviour and outcomes”21 (p. 695). | What is the most suitable methodology for assessing the CSR of businesses when both the concept of CSR and its evaluation are closely intertwined with the potential for irresponsibility on the part of the business in question? |

| McWilliams and Siegel | 2001 | CSR is “situations where the firm goes beyond compliance and engages in actions that appear to further some social good, beyond the interests of the firm and that which is required by law”22 (p. 1). | What methodological approach might be adopted to address potential discrepancies in conceptualising a social good among diverse social groups? |

| Hopkins | 2003 | CSR is “concerned with treating the stakeholders of the firm ethically or in a responsible manner. ‘Ethically or responsible’ means treating stakeholders in a manner deemed acceptable in civilised societies. Social includes economic responsibility. Stakeholders exist both within a firm and outside – for example, the natural environment is a stakeholder. The wider aim for social responsibility is to create higher and higher standards of living, while preserving the profitability of the corporation, for people both within and outside the corporation”23 (p. 10). | What are the criteria that could be applied to define a benchmark of a civilised society that would be universally accepted?What is the appropriate manner in which to represent nature as a meaningful stakeholder in this context? |

| Kotler and Lee | 2005 | CSR is “a commitment to improve community well-being through discretionary business practices and contributions of corporate resources”24 (p. 3). | Does this imply that the internal well-being of business organisations is not a relevant consideration? |

As illustrated by the table of selected definitions, there is considerable diversity in the methodologies employed to examine CSR, with approaches varying contingent on the research question and disciplinary context. A synthesis of the definitional approaches demonstrates that, in addition to pursuing economic objectives, organisations are obliged to assume social, ethical, and, in the case of more contemporary definitions, ecological responsibility. Consequently, CSR encompasses any corporate activity that is not aimed at maximising profit, but which benefits other stakeholders in some way.26

Following Lizarzaburu27, the fundamental aspects of CSR can be divided into five different subcategories, which are frequently mentioned in most definitions.

Firstly, by the 1970s, a consensus had emerged among academics and many contemporary authors that the concept of CSR entails a commitment to go beyond the economic, technical, and legal requirements of a firm. Secondly, there is a consensus among academics that CSR is a long-term concept that encompasses economic profit, social influence, and profitability. CSR must be the subject of strategic planning, implementation, and evaluation to align with the interests of the company. Secondly, it is important that CSR is not merely regarded as a mere facade or diversionary tactic from the core activities of the enterprise. Rather, it must be viewed as an integral and intrinsic component of the organisational mission.27 A third feature of CSR is the notion that companies are accountable to various stakeholders who can be identified and who have a claim – either legally stated or morally expected – on the business activities that concern them. In the discourse surrounding the accountability of businesses to their stakeholders, CSR is frequently associated with the concept of the social license to operate (SLO). SLO claims that a society is a unified entity, created and empowered by a state charter to act as an individual. This perspective confers upon businesses the right to own property, enter into contracts, and engage in legal actions. This exemplifies the degree of autonomy that would otherwise be available to companies if not for any moral constraints. The concept of a SLO implies that society permits companies the right to act in a fair and responsible manner, beyond the legal minimum, in exchange for which they assume certain responsibilities.28

The evolution of the concept of CSR is characterised by an expansion in scope to encompass a diverse range of principles, processes and outcomes. This evolution can be exemplified by the various definitions proposed by prominent figures in the field, including Bowen, Drucker, McWilliams and Siegel. These definitions encompass a range of elements, including ethical foundations, strategic integration processes, and economic analyses, collectively illustrating the multifaceted understanding of CSR. This understanding emphasises the necessity of integrating CSR into the fundamental strategies of organisations.

2 Distinction from similar topics

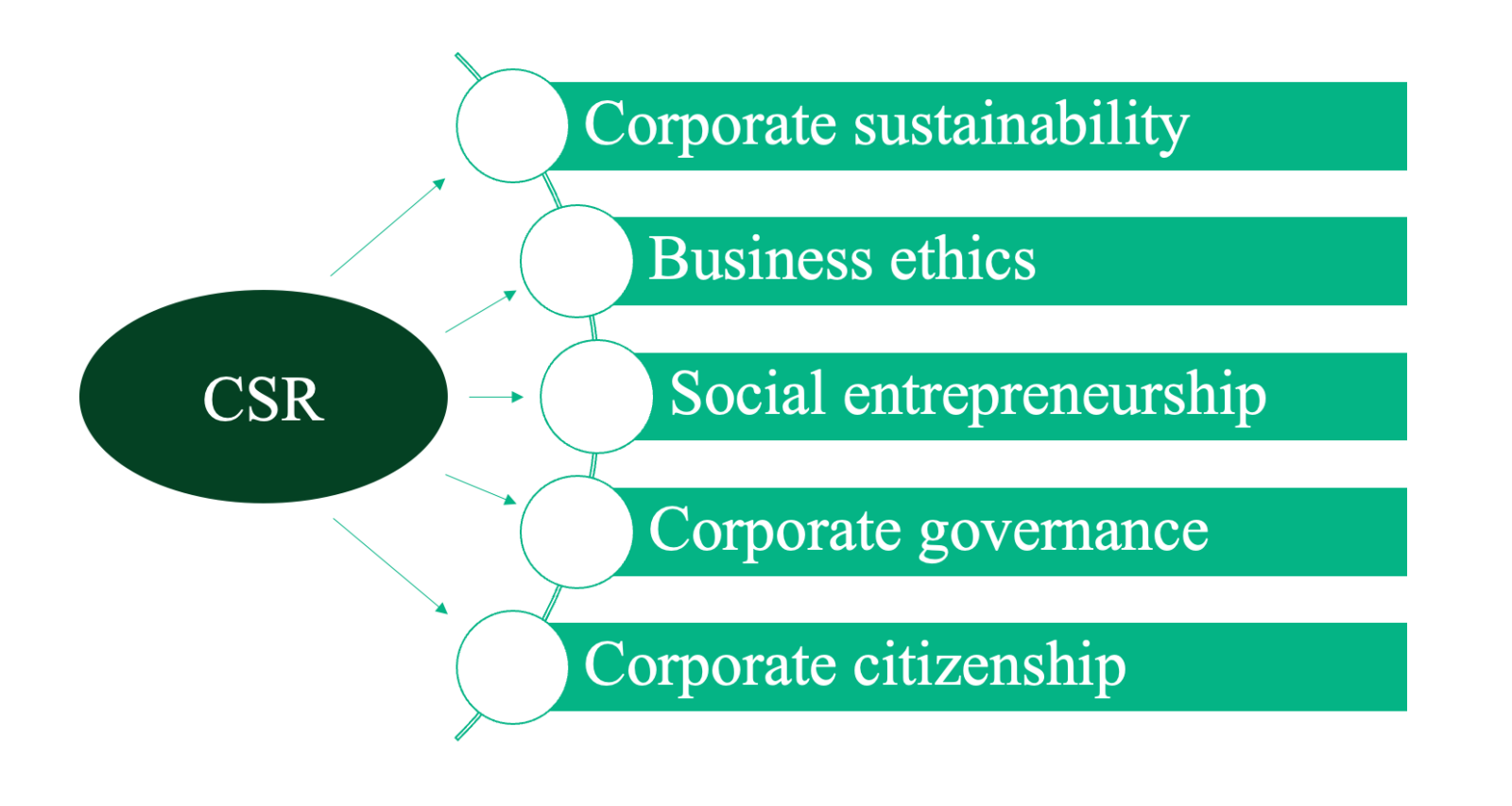

Due to the numerous interconnections between the field of CSR and other academic disciplines, CSR is often referred to as a cluster concept, as proposed by Matten and Moon in 2008.29 In contemporary business and scientific discourse, the term CSR is frequently associated with several related concepts. To elucidate the distinctions between this concept and related terms, a brief differentiation will be presented below. The following section will provide a brief overview of the various related concepts, outlining their similarities and differences to CSR. In particular, it will address the distinction between CSR and the following concepts: corporate sustainability, business ethics, social entrepreneurship, corporate governance, and corporate citizenship.

In the context of contemporary corporate governance and CSR, the concept of corporate sustainability (CS) has emerged as a key paradigm that extends beyond mere profitability to encompass a broader range of environmental and social imperatives.13 Although CS and CSR are frequently used as if they were synonymous, they represent two distinct yet interrelated frameworks for corporate responsibility.13 CSR encompasses a more expansive array of ethical, social, and environmental responsibilities, including philanthropic activities, ethical labour practices, and stakeholder engagement. Conversely, CS is focused on the long-term viability and resilience of businesses within a socio-environmental context.30

The field of business ethics examines ethical principles and moral dilemmas within business contexts, which intersect with CSR but may have different emphases and theoretical frameworks.31 CSR is a specific aspect of business ethics that emphasises a company’s social and environmental responsibilities beyond profit-making decisions.32 CSR is concerned with the company’s responsibility to society and the environment. It is regarded as a voluntary undertaking that goes beyond legal requirements. In contrast, adherence to business ethics often entails compliance with legal regulations, as it focuses on ethical standards and values that govern internal conduct.33,34 Both concepts facilitate the construction of a positive corporate reputation, the establishment of constructive relationships with stakeholders, and the mitigation of potential business risks associated with unethical conduct or social and/or environmental harm.33

Although both CSR and social entrepreneurship aim to promote social and environmental goals, they differ in terms of their approach, motivation, and impact.35 CSR involves the integration of social and environmental concerns into business operations with the aim of enhancing reputation and creating value for stakeholders. In contrast, social entrepreneurship is the creation of innovative business models with the objective of addressing social challenges in a sustainable and scalable way.36 Furthermore, CSR is often driven by a desire to enhance the company’s reputation, comply with regulations, or meet stakeholder expectations. While CSR may result in beneficial social consequences, it is ultimately a means to an end for the company. In contrast, social entrepreneurship is driven by a profound dedication to the creation of social impact and the driving of positive change in society.36

The corporate governance (CG) practices of organisations intersect with the domain of CSR, particularly with regard to matters of accountability, transparency and organisational structure. However, there are notable differences in terms of scope, objectives and regulatory framework.37 CG is primarily concerned with matters internal to the company, such as the management, control, and regulatory compliance of its operations. In contrast, the external focus of CSR encompasses the company’s impact on society and the environment. Moreover, CG is employed to delineate the systems and procedures that a company deploys to guarantee accountability, equity, and transparency in its operations. Such activities are frequently constrained by legal and regulatory requirements. In contrast, CSR is a voluntary practice, driven by the company’s commitment to ethical practices. CG, in its essence, pertains to the structures and processes that direct and control a company’s operations. It encompasses the relationships between a company’s management, board of directors, shareholders, and other stakeholders.38,39

The concept of corporate citizenship emphasises the responsibilities and obligations of corporations as members of society. While encompassing elements of CSR, it often focuses more on civic engagement and social contributions.40Corporate citizenship is used to describe a company’s commitment to addressing social issues that extend beyond its own business activities These activities are typically limited to the company’s local environment. ironment.30 Examples of corporate citizenship include donations and sponsorships (as known as corporate giving), the creation of benevolent company institutions (such as corporate foundations), and the direct involvement of company staff in social projects and initiatives (corporate volunteering).41 The CSR concept is far broader in scope, encompassing the fundamental responsibilities of the company and all of its contributions to sustainability, regardless of whether the activities in question form part of or lie outside the company’s ordinary business activity.42

3 Relevance of the topic

CSR has emerged as a central concept in contemporary business theory and practice, reflecting a paradigm shift towards more responsible and sustainable corporate behaviour.43 There are two principal reasons why companies may choose to engage with CSR: strategic or ethical. From a strategic perspective, CSR can contribute to corporate profits, particularly when brands proactively disclose the positive and negative outcomes of their CSR efforts. The business case for CSR claims that company value, shareholder confidence, and other stakeholder demands are interdependent and provide legitimacy for companies.44 Many corporations employ CSR methodologies as a strategic tactic to secure public support for their operations in global markets. This enables them to sustain a competitive advantage by leveraging their social contributions to provide a subconscious level of advertising.45 Top management may be motivated to implement CSR management systems either intrinsically or extrinsically.46 Companies with superior CSR tools can have a significant impact on their long-term financial benefits (e.g. increased cash flow, liquidity) and thus on their reputation with stakeholders. The utilisation of CSR measures by stakeholders, such as the evaluation of CSR performance or the assessment of CSR reporting quality, is employed in order to analyse the reliability of CSR management and related firm risks.46 Ethical considerations also constitute a significant factor in the implementation of CSR. Nevertheless, for many organisations, ethical reasons also constitute a significant factor in the implementation of CSR. The implementation of CSR remains predominantly voluntary. In this context, reference is made to the self-regulatory mechanisms of companies.46

However, the implementation of CSR is becoming increasingly subject to legal constraints and measures. There is a global trend towards greater state regulation. Moreover, an increase in indirect state pressure and the application of private law by private actors can be observed, the latter of which employ use of this in highly innovative ways.47Currently, contemporary national legislation and regulations establish minimum standards for corporate conduct in areas such as human rights, environmental protection, consumer protection, and civil rights. This defines the legal framework within which CSR initiatives are conducted. Some companies base their definition of CSR on international and national legislation.48 Consequently, CSR is currently regarded as a form of de facto economic law and is increasingly being used as a means of addressing the social impacts of industry.49 However, in many legal systems, CSR implementation remains primarily voluntary, with companies relying on self-regulatory mechanisms. The concept of CSR is not clearly defined, which results in uncertainty regarding its relationship with other domains, including politics, social costs, and corporate law.50 However, the growing legal obligation pertaining to CSR renders it a pivotal concern for organisations.

The integration of multidisciplinary perspectives from fields such as economics, sociology, psychology, ethics, and environmental sciences is a fundamental aspect of CSR research, which aims to advance an understanding of the ethical, social and ecological dimensions of corporate behaviour. CSR theory should provide a basis for the development of normative frameworks, measurement tools and evaluation criteria for assessing the impact and effectiveness of CSR initiatives.39

4 Historical development of CSR

The concept of CSR has a history spanning almost a century, although its origins can be traced back much further. The following section will present an overview of the historical roots, the historical development, and the milestones that have led to the current state of CSR.

4.1 The origin of CSR

In ancient civilisations, business practices were often guided by ethical and religious principles. For example, the Code of Hammurabi, which originated in ancient Mesopotamia, included provisions designed to protect consumers and ensure fair business practices.51 Many scholars have traced the historical roots of CSR back to ancient Greece and Rome, where wealthy individuals and business owners were often engaged in philanthropic activities, funding public works, educational institutions, and charitable causes out of altruistic motives.42

The history of the honourable merchant from the 12th century undoubtedly serves as a crucial foundation for the contemporary discourse on CSR. The honourable merchant epitomises the archetypal businessman, one who not only sought personal profit but also considered ethical principles and social responsibility into account in his actions. This model exemplifies responsible engagement with the economic landscape in Europe. It symbolises a robust sense of responsibility for one’s own company, for society and for the environment. An honourable businessman is guided in his behaviour by virtues of prudence, frugality, and perseverance, with the aim of attaining long-term economic success without acting in a manner that contravenes the interests of society.52 The honourable merchant is distinguished by integrity, which encompasses honesty and reliability in all business transactions. For the honourable merchant, fair treatment of customers, suppliers, and employees represent a fundamental principle. Furthermore, the honourable merchant assumes responsibility for the impact of their business on society and the environment. They engage in prudent financial management and make well-considered decisions. Moreover, the honourable merchant is dedicated to upholding local and international legislation, cultural norms and values, and to supporting social communities.53Consequently, the principles espoused by the honourable merchant remain fundamental to contemporary CSR, whereby businesses integrate social and environmental concerns into their operations and interactions with stakeholders.54

During the Renaissance and the rise of capitalism in the 16th century, the status of the honourable merchant was particularly elevated in various European trading centres, including Florence and Antwerp. These individuals were celebrated for their integrity, business ethics, and dedication to social responsibility within their communities. The concept of the honourable merchant was subsequently adapted and developed in other parts of the world.55 In his 1776 treatise, The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith argued that in the pursuit of profit and efficiency, the economy ultimately serves the interests of both the firm and society.56

The advent of the Industrial Revolution at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century marked the onset of a period of profound economic and social transformation.57 The rapid industrialisation and the rise of large corporations gave rise to several significant social issues, including poor working conditions, child labour and environmental degradation.58 In response to these challenges, early industrialists and social reformers advocated for the implementation of more responsible business practices. Notable figures such as Robert Owen, a pioneer of social reform, implemented progressive working practices and community initiatives at his textile mills in New Lanark, Scotland.59 However, for a considerable period of time, there was also no scientific debate on the subject.

Heald identifies two early programmes from the early 20th century as evidence of a degree of CSR, despite the fact that they were never explicitly mentioned under that concept. These programmes were initiated by business leaders such as Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller, who were engaged in philanthropic activities.60,61 Furthermore, Heald suggests that the 1918-29 community chest movement also helped shape business views on philanthropy, which represents one of the earliest forms of CSR.61

In their analysis of the period up to this point, Robert Hay and Ed Gray identified it as the phase of profit-maximising management in the development of social responsibility. The second phase, which they called fiduciary management, emerged in the 1920s and 1930s as a consequence of alterations in both the economy and society. Consequently, in their view, the role of the manager was increasingly perceived as a trustee for the various groups with whom the firm had a relationship, rather than merely that of a representative of the firm.62 In their view, fiduciary management entailed that managers assumed responsibility for maximisation of shareholder wealth and for the creation and maintenance of a fair equilibrium between competing interests, including those of customers, employees and the community.

During the 1930s and 1940s, a number of works were published, including Chester Barnard’s (1938) The Functions of the Executive, J.M. Clark’s (1939) Social Control of Business and Theodore Kreps’ (1940) Measurement of the Social Performance of Business, which provided the inaugural foundational literature on CSR.11 With the expansion of business in the 1940s and the Second World War, Eberstadt claims that companies operated under the assumption that they were discharging their social responsibilities by espousing anti-communist sentiments.63

4.2 1950s and 1960s

During the 1950s, the notion that businesses had responsibilities extending beyond mere profit-making began to gain modest acceptance among business leaders and academics across the globe. The discourse on CSR was primarily theoretical in nature, focusing on the ethical obligations of businesses to society. One of the earliest works to address the concept of CSR in a systematic manner is Howard Bowen’s 1953 publication, entitled Social Responsibility of the Businessman. In his argument, he claims that businesses have an ethical responsibility that extends beyond the mere pursuit of profit. Moreover, he asserts that businesses exert a considerable influence on a range of societal domains, including economic prosperity, social structure, and public well-being. Consequently, businesses are advised to consider the social impact of their actions. Bowen puts forth the proposition that social responsibility should be incorporated into the fabric of business practices and decision-making processes. Furthermore, Bowen suggests that businesses adopt a long-term perspective, with a particular focus on the potential impact on future generations. To date, the work has remained a foundational conceptual framework for CSR.18,60

The 1960s were a period of significant social and political upheaval, including the civil rights movement, which served to increase public awareness of social justice issues. During the 1960s, academics continued to develop and expand the concept of CSR. Similarly, Keith Davis advanced the notion of the Iron Law of Responsibility, which postulates that the social responsibilities of businesses should align with their social influence.60 During this period, consumerism emerged as a significant social phenomenon, characterised by consumers becoming increasingly vocal about their rights and expectations. This shift in consumer behaviour prompted businesses to acknowledge the necessity of ensuring product safety, upholding consumer rights, and practising ethical marketing as integral aspects of their social responsibilities, thereby intensifying the pressure on companies.60

4.3 1970s

During the 1970s, there was a notable expansion and formalisation of CSR. Over time, there was a broader acceptance of, and more formal definitions of, CSR. The 1970s constituted a transformative decade for the field of CSR, characterised by a shift from philanthropic activities to more strategic and integrated approaches. The transformation was also influenced by social and environmental movements, as well as increased regulatory pressures. In 1970, Milton Friedman published the work The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits, which initiated a significant debate by arguing that the sole responsibility of business was to maximise shareholder value within the bounds of the law.60 A detailed examination of Friedman’s theory will be presented in section 3.2.1.

Conversely, other scholars began to articulate a more expansive set of responsibilities for businesses. Wallach and McGowan’s 1970 formulation of enlightened self-interest provided a compelling rationale for businesses to integrate CSR into their strategic planning. This demonstrated that responsibility and economic success are not mutually exclusive but mutually reinforcing.64 Keith Davis expanded on his earlier work with the idea that businesses must balance power with responsibility. By 1977, almost half of the Fortune 500 global companies had already incorporated CSR into their business objectives and were actively highlighting their CSR activities in their annual reports.65,66 In 1971, the inaugural US committee on the social responsibilities of business corporations was convened. In 1972, the Club of Rome, an association of experts from diverse disciplines from over 30 countries, published The Limits to Growth, regarded as one of the most significant works on ecological and social economic development.65

In 1979, Carroll introduced his four-part definition of CSR, which will be subsequently elaborated upon in section 3.2.4.60

4.4 1980s and 1990s

The 1980s and 1990s were a period of significant institutionalisation and deeper integration of CSR into business strategies and practices. In 1984, Edward Freeman published Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach, in which he claims that organisations should consider the interests of all stakeholders in their decision-making processes. This theory represents a shift from a shareholder-centred to a stakeholder-centred view, signifying a profound transformation in the manner in which companies approach their responsibilities. A detailed examination of this shift will be provided in section 5.2.1

Furthermore, CSR began to be regarded not merely as a peripheral undertaking, but as an intrinsic component of the corporate strategy. The process of strategic integration entailed the alignment of CSR initiatives with the core objectives of the business, the utilisation of CSR as a means of gaining a competitive advantage, and the embedding of CSR within the organisational culture and operational framework. Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and activist groups gained greater influential in holding companies to account for their social and environmental impacts.60Campaigns and boycotts by organisations such as Greenpeace and Amnesty International elevated public awareness and exerted pressure on companies to adopt more responsible practices. The occurrence of numerous instances of corporate fraud and financial misconduct served to illustrate the potential danger inherent in the neglect of CSR. In order to prevent misconduct, companies began to adopt stronger governance structures, internal controls and transparency measures.60

In the 1990s, a number of significant international events had a considerable impact on the international perspective on social responsibility and the approach to sustainable development. The most significant of these were the establishment of the European Environment Agency in 1990, the United Nations (UN) Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro, which resulted in the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, the adoption of Agenda 21 and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1992, and the adoption of the Kyoto Protocol in 1997.67

In order to introduce a comparable and objective monitoring body, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) was established in 1997 by CERES, an NGO based in the US, and the UN Environmental Programme. The objective of the GRI is to provide a framework for sustainability reporting. This pioneering initiative standardised the reporting of economic, environmental and social performance, thereby facilitating the evaluation and comparison of companies’ CSR efforts by stakeholders. Moreover, studies conducted during the 1980s and 1990s began to explore the relationship between CSR and financial performance. These studies frequently revealed that companies with a strong CSR profile often demonstrated superior financial results. By the late 1990s, the concept of CSR had gained significant recognition, being widely acknowledged and “promoted by all constituents in society”65 (p. 53), including governments, companies, NGOs, and individual consumers.

4.5 2000 to present day

The twenty-first century is characterised by the globalisation of trade and finance, which has resulted in a constant transformation of the economic environment and of economic and social progress.68 Since the turn of the millennium, CSR has undergone a significant evolution, moving from a peripheral concern to a central and indispensable component of corporate strategy and governance. This evolution has been marked by the establishment of global frameworks and standards, a heightened focus on transparency, supply chain responsibility, and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria, and the emergence of CSR as a fundamental aspect of how businesses operate and contribute to society.65

The UN Global Compact was established in 2000 with the objective of encouraging businesses worldwide to adopt sustainable and socially responsible policies. The ten principles are based on universally accepted principles concerning human rights, labour, the environment and anti-corruption.69 In 2001, the GRI published guidelines for sustainability reporting, which have since become a global standard, promoting transparency and accountability.70 In 2004, CSR was incorporated into the Lisbon Strategy of the European Union (EU), thereby underscoring its pivotal role in sustainable economic development. In 2006, the Principles for Responsible Investment were established with the objective of encouraging investors to consider ESG-criteria in their investment decisions.71 The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) released ISO 26000, a guidance standard for social responsibility in 2011.72 The collapse of the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh in 2013 revealed the precarious nature of working conditions in the supply chain and highlighted the responsibility of multinational companies and their suppliers. This resulted in an increased demand for transparency within the supply chain.73

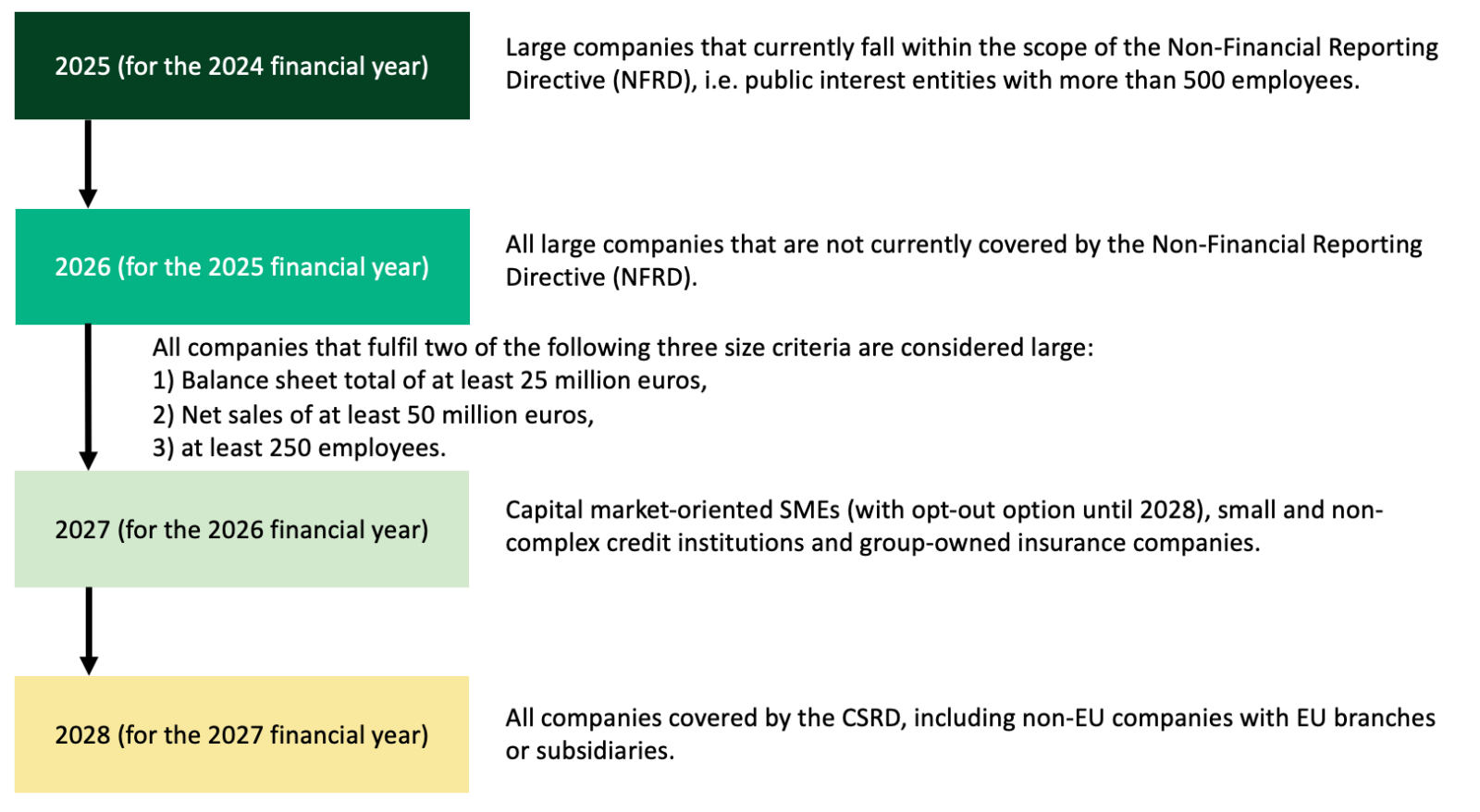

In 2015, the UN introduced the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. These goals address a range of social, economic, and environmental issues, and encourage companies to adopt sustainable practices in order to contribute to their achievement.74 In 2018, the European Commission put forth the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD), which aims to enhance and standardise corporate sustainability reporting within the EU. The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) represents an updated and strengthened iteration of the existing NFRD. It is scheduled to replace the previous NFRD in 2025, with the objective of providing stakeholders with a more comprehensive and reliable source of sustainability and CSR information. This will be achieved through a double materiality assessment of companies. The directive’s objective is to guarantee that companies furnish comprehensive and dependable data concerning their sustainability performance, taking into account both internal and external impacts. The implementing of the CSRD by the EU is intended to enhance transparency and comparability in sustainability reporting, thereby promoting corporate accountability and facilitating informed decision-making by stakeholders.67,75 A detailed explanation of the CSRD can be found in Section 7.1.4 in the context of reporting standards.

In the contemporary business environment, CSR is regarded as a pivotal strategic element, with a critical role in the long-term sustainability of organisations. Consequently, CSR has emerged as a crucial decision-making process within organisations, affecting both sustainability and stakeholder interests.76 The importance of CSR in the business sector has increased noticeably in recent years. A recurring assertion in the literature is that companies pursue a greater social commitment in order to enhance their profitability relative to their less socially committed competitors.76

The following section presents an in-depth examination of the theoretical approaches to CSR.

5 Theoretical approaches to CSR

The holistic concept of CSR has been the subject of scientific inquiry since the mid-1970s. Notwithstanding the absence of consensus regarding the precise definition of CSR and the considerable number of scholars engaged in its study, a multitude of theoretical frameworks and approaches have emerged. It is noted that no universally accepted theory of social and environmental accounting exists. The following table provides an overview of the most prevalent theoretical approaches to CSR, as identified by Stephens and Frynas.77

| Perspective | Theory/ concept | Proponent/ author | Description |

| Economic-instrumental approach | Market-based approach | Porter and Kramer | Creating shared value as a strategic approach that seeks to align social and economic goals. |

| Resource-based view and the dynamic capabilities theory | Penrose | Consider the way in which CSR is being utilised as a distinct skill or capability to gain a competitive advantage. | |

| Integrative approach | Stakeholder theory | Freeman | Describes the evolving role of CSR in responding to the diverse expectations of stakeholders. |

| Institutional theory | Powell and DiMaggio | Describes the changing functions because of companies’ conformity to different institutional pressures. | |

| Resource dependence theory | Pfeffer and Salancik | Framework for how firms oversee their reliance on pivotal resources subject to the influence of external stakeholders. | |

| Legitimacy theory | Dowling and Pfeffer | Examines the emergence of CSR as a strategy for achieving legitimation through congruence with the norms and values of the society in which they operate. | |

| Political approach | Integrative theory of social contracts | Donaldson and Dunfee | Presents a detailed account of the potential political role of companies and the ways in which this could be achieved. |

| Rawlsian theory | Rawls | Employs Rawls’ theory of justice to ascertain the just (and legitimate) rights and responsibilities of a corporation as a social and political entity. | |

| Habermasian theory | Habermas | Draws upon both Habermasian discourse ethics and deliberative democracy to provide an account of the ways in which CSR can be legitimised. |

5.1 Economic-instrumental approach

The first group of theories can be classified as economic-instrumental theories, as they regard CSR as a mere instrument for achieving financial gain and profit maximisation.78 The trade-off theory proposed by Milton Friedman, as outlined in his 1970 New York Times article, A Friedman Doctrine: The Social Responsibility of Business Is To Increase Its Profits, represents the most common economic-instrumental approach to the concept of CSR.79 Friedmann’s argumentation adheres to the established pattern of neo-liberal argumentation. Consequently, organisations will only allocate resources to social and societal issues if social investments or responsible process design enhance a positive contribution to the value of the company.80

In accordance with Friedmann’s foundational argumentation, three principal lines of development of economic-instrumental concepts can be discerned, which are characterised by the common objective of enhancing corporate value through CSR investments. These will be presented in detail below.

5.1.1 Market-based view

The market-based view(MBV), as outlined by Porter and Kramer (2006), places an emphasis on CSR through their concept of creating shared value (CSV). This approach reframes the role of corporations in society, emphasising the necessity for the integration of social and economic progress. The assertion is made that companies can gain a strategic competitive advantage through targeted investments in the business environment and adaptation to market structures. This approach postulates that corporations bear responsibility not only to their shareholders, but also to society at large.81

Porter and Kramer put forth the argument that conventional CSR initiatives tend to place a greater emphasis on reputation management than on tangible social impact. They argue that CSR activities are often detached from the core business, which results in limited effectiveness. Conversely, they regard CSV as a strategic methodology that harmonises social and economic goals, thereby enhancing sustainability and impact. Such integration serves to fosters trust in corporations and to reinforce their legitimacy in society.81

As part of the MBV, CSV can encompass a wide range of initiatives. To illustrate, the enhancement of local production factors through employee training can facilitate the improvement of the workforce’s skills, consequently increasing the company’s productivity and capacity for innovation.82 Moreover, the advancement of infrastructure in a region can not only support the company’s operations, but also reinforce the economic environment as a whole, thereby facilitating to a more extensive engagement with stakeholders.80 It can be demonstrated that the concept of CSR has evolved from the repatriation of profits to society, with the objective of CSV with stakeholders.81

A significant objective of this engagement is to exert an influence on alterations in consumer demand patterns. By promoting education and technology, companies can not only enhance the positioning of their positioning of their own products and services, but also raise the overall level of economic development in the region. This can result in an increase in purchasing power and a more stable demand, which is beneficial for the company.81

5.1.2 Resource-based view and the dynamic capabilities theory

The resource-based view (RBV) and the dynamic capabilities theory represents a research stream with origins in the work of Edith Penrose. Penrose offered significant insight into the processes of resource acquisition, utilisation, and expansion, which are key to gaining competitive advantage.80 The dynamic capabilities theory, in particular, underscores the significance of a firm’s internal resources and capabilities in the creation and maintenance of a competitive advantage.83 This is in contrast to the industry-level analysis favoured by Porter and Kramer in the market-based approach, which focuses on the central role of firm-level resources (such as workforce, finances, expertise, etc.).84 The RBV approach allows for a cost-benefit analysis of CSR initiatives in competitive markets.85

The term firm dynamic capabilities is defined as the capacity of a firm to integrate, learn and reconfigure both internal and external resources.86 This theory proposes that firms must possess resources that are valuable, rare, imperfectly imitable, and non-substitutable in order to establish and maintain a sustainable competitive advantage.87 Furthermore, the more specifically these resources are subsequently utilised, the greater the potential competitive advantage. The process of moral decision-making, sensitivity, and responsiveness regarding the corporate environment and key stakeholders has considerable potential, especially in terms of a dynamic competitive advantage regarding long-term challenges.86 From the perspective of the RBV and the theory of dynamic capabilities, the integration of CSR into the core activities of a company can lead to a long-term increase in the value of the company for its stakeholders. This is accomplished by concentrating on distinctive and valuable resources and cultivating dynamic capabilities for adaptation and innovation.86,88

The differentiation between entrepreneurial activities that generate economic benefits through socially responsible investments and those that merely pursue economic interests under the pretext of social responsibility represents a significant challenge for all economic-instrumental concepts.

5.2 Integrative approach

The integrative perspective on CSR is based on a range of theoretical approaches that seek to comprehend and operationalise CSR as an intrinsic element of corporate strategy and practice. An integrated approach to CSR entails the alignment of corporate strategies with societal objectives, thereby ensuring that business operations contribute to sustainable development. This approach acknowledges the interdependence between business strategy and public policy objectives.89

The following section presents an integrative approach to CSR based on the stakeholder theory, the institutional theory, the resource dependence theory and the legitimacy theory.

5.2.1 Stakeholder theory

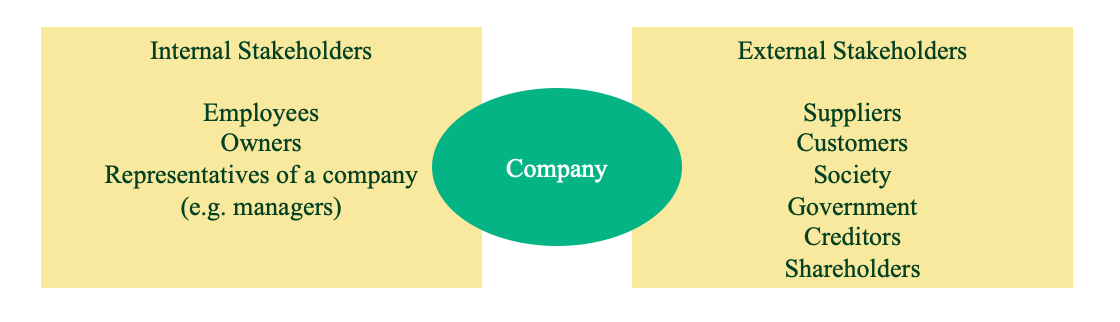

The stakeholder theory, as proposed by Freeman in 1984, represents a well-established construct in the context of integrative CSR approaches. Freeman defines stakeholders as individuals and groups that exert influence over a company and/or are affected by its activities in some way.90 In accordance with Freeman’s stakeholder theory, the categorisation of CSR should be determined on the basis of the stakeholders involved. The involvement of stakeholders can facilitate an analysis of the relationship between a firm and its broader environment.91 The notion of stakeholders is predicated on the assumption that, insofar as shareholders are entitled to expect certain actions from management, “stakeholders are most entitled to submit claims”92 (p. 35). The theory postulates that businesses bear an ethical obligation to engage with stakeholders and address their interests, given that their actions can have a profound impact on the well-being of these stakeholders and the sustainability of the business. By incorporating employees, environmentalists with close ties to the company’s operations, vendors, government agencies, and more, Freeman claims that a company’s true success lies in satisfying all stakeholders, not just those who might benefit from its shares.90 In their respective works, Freeman and Clarkson (1995) distinguished between primary and secondary stakeholders.90,93 Similarly, Verdeyen, Put, and Buggenhout (2004) proposed a categorisation of stakeholders as either internal or external to the business environment.94

Crane and Matten provide further elaboration on this concept in the context of CSR. Accordingly, a company’s stakeholders are individuals and groups that directly benefit or suffer from the company’s actions, or whose rights must be respected. This perspective treats all groups affected by a company’s actions as equal.3 Based on the findings of various studies on the concept of stakeholders, it can be inferred that organisations should align their CSR initiatives with the probable preferences of their stakeholders and undertake socially responsible actions that are pertinent to the organisation’s strategic objectives. The stakeholder theory postulates stakeholder dialogue as an ideal target position. The objective of the dialogue between companies and their primary stakeholders is to create value collectively and to achieve consensus.95 In the literature on social and ecological accountability, there has been a notable focus on the representation of stakeholders and their enhanced influence, in accordance with the principles of stakeholder democracy.21

| Actor | Process | Outcome |

| Private sector | Practice CSR | More efficient business, greater share price long-term business success. |

| NGO | Putting CSR in practice by stakeholder dialogue and consultation | Meaningful change in the behaviour of organisations. |

| Government | Light – touch regulation | Assist organisations in addressing sustainability issues. |

| Local population | Positive stakeholder relationship created by CSR | Less negative impact on local population and more constructive engagement with the community. |

| General public | Transparency created by CSR | Enhanced quality of social life. |

| Supplier | Through the supply chain: pressure from larger corporations | SME participation in CSR. |

| Employees | Positive stakeholder relationship created by CSR | Motivated, engaged, involved, trained and committed workforce. |

| Clients | Pressure on corporations | Better quality of goods and services |

| Shareholders | Active social responsible investment | Consider ways of creating a market for CSR, which could potentially lead to an increase in share prices. |

5.2.2 Institutional theory

The institutional perspective, particularly the approach of New Institutionalism, as proposed by Powell and DiMaggio in 1991, is based on a comprehensive examination of the interactions between institutional structures and organisational processes.97 In this context, the term institutions is used to refer to collective and regulatory complexes comprising political and social agencies. It can be argued that institutions exert a dominant influence over other organisations through “the enforcement of laws, rules and norms that constitute both formal rules and informal constraints”98 (p. 97).

This theory represents a discrete branch of the integrative approaches to CSR, placing particular emphasis on the influence of institutional norms, values, and regulations on organisational behaviour.99

The perspective proposes that organisations are situated within a broader institutional context that shapes their behaviour, practices, and norms. This context encompasses formal institutions, including cultural norms, social expectations, and industry conventions. Accordingly, the institutional theory claims that organisational forms are best described and explained. The rationale behind the emergence of homogenous characteristics or forms within a given organisational field is elucidated.100 Consequently, it is crucial for organisations to legitimise and accept themselves within their environment. A failure to adhere to the prevailing institutional norms may result in sanctions or a loss of legitimacy.99,101

Accordingly, the institutional theory postulates that CSR should not be regarded as a mere area of voluntary activity, but rather as a field of economic governance encompassing a multitude of modes, including the market, state regulation, and other forms of governance.101 Furthermore, the institutional theoretical perspective enables the investigation and comparison of motives within their national, cultural, and institutional contexts. This approach allows for the explanation of the disparate definitions of CSR that are observed across the globe. By contemplating the distinctive institutional contexts of disparate regions, researchers and practitioners can gain a more profound comprehension of the factors that contribute the variation in CSR practices across countries and cultures.102

5.2.3 Resource dependence theory

The Resource Dependence Theory (RDT), originally formulated by Jeffrey Pfeffer and Gerald R. Salancik in 1978, represents a further integrative approach to organisational studies. This theory asserts that organisations are not self-sufficient entities, but rather interdependent on external resources for their survival and success.103 In the context of CSR, RDT provides a framework for the analysis of how firms manage their dependencies on critical resources controlled by external stakeholders. CSR activities can be regarded as a strategic response to the aforementioned dependencies. The objective of these activities is to secure essential resources, including legitimacy, capital, and market access.104

Furthermore, RDT postulates that organisations are dependent on their external environment to ensure the continued availability of critical resources for their survival. Consequently, organisations are obliged to consider the needs of those who provide resources for their continued existence.105 In the event that a company is unable to fulfil all of its obligations, RDT predicts that it will seek to engage with those actors who possess control over critical resources. In the academic literature, there is a consensus that large purchasers represent a significant external procurement channel and stakeholder for suppliers. The implementation of CSR initiatives frequently necessitates interaction with large purchasers and the establishment of a relationship with them. Consequently, RDT, which focuses on resources and relationships, is closely linked to the relationship between supplier dependence and supplier CSR. Furthermore, there is a correlation between RDT and the field of institution theory, as evidenced in the academic literature.106 It is important to make a crucial distinction here. While institution theory allows for strategic decision-making, the RDT explicitly endorses this approach.105

Child and Tsai (2005) have employed the institutional theory in conjunction with the RDT, as the former alone proved inadequate for elucidating the manner by which organisations may proactively seek to influence political outcomes.98By drawing on insights from the RDT, the authors demonstrated how companies employed strategic influence to shape “environmental regulation in China”77 (p. 491). The authors concluded that “institutions are more open and pervious to corporate strategic action than is often allowed for in the literature”98 (p. 118).

5.2.4 Legitimacy theory

The Legitimacy Theory of CSR was initially proposed by John Dowling and Jeffrey Pfeffer in their 1975 article, Organizational Legitimacy: Social Values and Organizational Behavior.44 The theory has been the subject of further development and refinement by other scholars, most notably Mark Suchman, who provided a comprehensive definition of legitimacy and its importance for organisations in 1995. Suchman defines legitimacy as “a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions”107 (p. 574).

The legitimacy theory postulates that organisations must demonstrate their legitimacy by exhibiting conformity to the prevailing norms and values of the social system within which they operate. When an organisation is perceived as legitimate, its actions are regarded as desirable, proper, or appropriate within a socially constructed system of norms and beliefs.108

The legitimacy of an organisation can be attributed to a number of different factors. The relative importance, difficulty and effectiveness of the legitimacy efforts may vary depending on the specific objectives being measured. In accordance with the tenets of legitimacy theory, firms are inextricably linked to society and lack an inherent right to exist. The continued existence of an organisation is contingent upon the conferral of legitimacy by society.105 The implementation of legitimacy theory indicates that organisations utilising CSR to enhance their legitimacy may potentially derive several benefits. Such outcomes include enhanced ratings in corporate governance, increased attractiveness to investors and reputational gains.109 In the academic literature, studies on legitimacy can be divided into two main approaches: the strategic and the institutional legitimacy. The concept of strategic legitimacy suggests that there is a certain degree of managerial control over the legitimation process. In contrast, the institutional legitimacy approach typically involves reactive conformity to existing norms and standards.107 The legitimacy of an entity is influenced by the theories of stakeholder and resource dependence. The emphasis is therefore on the relevance of resources and the necessity for management to consider the control of these resources.109

It is erroneous to view legitimacy theory and stakeholder theory as mutually exclusive approaches. Rather, they can be regarded as complementary, with significant interrelationships. Whereas legitimacy theory is concerned with the expectations of society in general, stakeholder theory is focused on the interaction of an organisation with specific groups within society.110

5.3 Political approach

The term political CSR is employed to categorise activities that are either intentionally or unintentionally imbued with a political dimension, or that are either directly or indirectly shaped by political factors within the context of CSR. In this context, the term can be defined as encompassing all effects related to the functioning of the state as a discrete area of activity distinct from business activities.77 However, it could be suggested that the term is best defined as encompassing all effects related to the functioning of the state as a discrete area of activity distinct from business activities.

5.3.1 Integrative Theory of Social Contracts

The transnational approach to CSR is arguably best exemplified by the Integrative Theory of Social Contracts (ISCT) in the field of CSR literature.111 Developed by Thomas Donaldson and Thomas Dunfee in 1994, ISCT provides a framework for examining and evaluating the moral obligations of companies towards their various stakeholders.112

The ISCT is predicated on the assumption that social contracts exist at two discrete levels. These can be classified as micro- and macro-level contracts. The term micro-contract is used to describe specific agreements that are made within communities, organisations or cultures. The values and norms of a particular group are reflected in micro-contracts, which may vary in their specifics. Nevertheless, their validity is contingent upon the absence of any contradiction with the universal macro-contracts. In contrast, macro-contracts represent universal ethical principles that serve as fundamental norms for all individuals. They provide the foundation for the ethical evaluation of actions and decisions, transcending cultural and geographical boundaries. Examples of such principles include human rights and basic standards of justice.113 The fundamental methodology of the ISCT is based on the obligation of multinational managers to initially examine the microsocial “contracts in the relevant communities”113 (p. 260), to question their authenticity, and then to compare them with fundamental norms at the macro level. This process is designed to ensure that the legitimacy of these contracts is upheld.

The objective of ISCT is to integrate both empirical and rational approaches to business ethics.113 Despite its origins in the field of business ethics, ISCT offers a perspective on the ethical obligations of companies in the context of CSR. It enables the incorporation of local norms and values into a global context while upholding universal ethical standards.114

A review of the existing literature reveals a prevalence of discussions surrounding ISCT. The growing prominence of the contractarian approach as a theoretical perspective reflects a growing concern with the legitimisation of corporate activity.21 The business-specific application of the social contract provides a means of explaining and legitimising the political and social involvement of business without reliance on state regulation or, indeed, a legitimate state.77

Furthermore, numerous studies employed the concept of the social contract as outlined in political philosophy, particularly the Hobbesian and Lockean interpretations.115

5.3.2 Rawlsian theory

In 1971, Rawls published A Theory of Justice, which provides a further framework for understanding CSR.116 Based on the principles of fairness and justice, Rawls underscores the moral and ethical responsibilities of corporations within society. In this context, Rawls puts forth two complementary principles:

The principle of equality, which asserts that all individuals should enjoy the same fundamental rights and freedoms, and the principle of difference, which recognises the existence of diverse groups with varying needs and interests.117 In this context, it is the responsibility of companies to ensure that their business practices respect the fundamental rights of all stakeholders. This necessitates the provision of equitable working conditions, equal opportunities for all employees, and the prevention of discrimination.118

The difference principle allows for the existence of inequalities, if they benefit the least advantaged. This indicates that organisations should utilise their resources and profits in a manner that improves the quality of life for those in disadvantaged communities. In this context, it is particularly noteworthy that investments in social projects, educational programmes and sustainable development are to be encouraged.118

As outlined in 3.2.3.1, ISCT and the Rawls’ theory can elucidate the responsibility of companies without naming the state as the addressee. However, they permit only limited insight into the institutional framework that is necessary for the realisation of these responsibilities. Consequently, this theoretical approach is unable to bridge the legitimacy gap that has emerged as a result of the transformation of global governance structures.77 The integration of Rawls’ theory into the field of CSR necessitates a shift in focus from the mere pursuit of profit to a model that prioritises ethical governance and sustainable development. Accordingly, Rawls claims that it is the moral obligation of companies to promote fairness and justice, extending beyond mere compliance with regulations. This suggests that companies have a responsibility not only to comply with legal obligations, but also to consider taking proactive measures to promote social justice.118

5.3.3 The theory of J. Habermas

The theory of deliberative democracy, as developed by Jürgen Habermas, postulates that political processes have their genesis at the level of consultative civil society associations.119 The concept of the post-national constellation, another concept of Habermas, can be employed to elucidate the decline of legitimacy of nation-states and the rise of political CSR, with specific reference to the attenuation of democratic control and the proliferation of cultural, value, and lifestyle pluralism as “challenges to the democratic order on a global scale”77 (p. 491f). This theory has been adopted by numerous authors as a means of conceptualising the increasing significance of private entities in global governance processes.120 In particular, the theory can elucidate the emergence of corporations, the ascendance of NGO coalitions, and the advent of multi-stakeholder initiatives as legitimate political actors.77

The application of Habermas’ theories to the field of political CSR provides a normative explanation for the legitimisation of companies’ political CSR activities. This body of literature draws on Habermas’ concept of deliberative democracy and addresses the procedural legitimacy of political CSR. The deliberative democracy alternative seeks to address the legitimacy gap that arises from the “involvement of non-state actors in political decision-making”77 (p. 492) processes. This perspective proposes that the political influence of corporations must be counterbalanced and legitimised through the establishment of a novel democratic system. It is proposed that the nation state is the most appropriate institution for implementing and safeguarding these novel institutions. Those who adopt this position contend that it is will ensure democratic accountability at the societal level and establish the nation state as the dominant institution.119,121

Furthermore, Habermas’s concept of the public sphere constitutes a substantial theoretical contribution to the comprehension of the dynamics of public discourse and its implications for democratic societies. The public sphere can be defined as a place or a domain of social life where individuals can engage in discourse and collectively shape public opinion, without the influence of coercion or inequality.122

In the context of CSR, the public sphere serves as a platform for stakeholders to engage in dialogue with corporations. Consequently, the public sphere enables transparency and accountability, as organisations are obliged to substantiate their procedures and policies in the presence of public examination. In addition to transparency and accountability, the public sphere encompasses the stewardship of public goods. It is imperative that oceans, rivers, land and air, which are vital public goods, are not exploited or polluted by corporations without consequences. These resources are the collective property of all members of society, and the maintenance of their health and sustainability is of critical importance to the general well-being of the population.123 It is crucial for companies to acknowledge their obligation not only to their shareholders but also to the wider community that depends on these essential public resources. By engaging in the public discourse, companies can demonstrate their commitment to ethical practices and social responsibility. Moreover, such participation contributes to the formation of a more informed and engaged citizenry, which is better equipped to hold companies to account.124

The following section presents an overview of the Carroll CSR model, which is widely regarded as the most prevalent CSR model.

5.4 Carroll’s CSR model

CSR can be viewed from a normative perspective, and may be considered in terms of both a short-term (tactical) and a long-term (strategic) focus.125 The earliest theoretical work dealing specifically with CSR was published by Sethi in 1975.19 In this work, he developed a three-stage model for classifying corporate behaviour, which he called corporate social performance (CSP). The three levels of corporate behaviour are based on social obligation (responding to legal and market constraints), social responsibility (dealing with social norms, values and performance expectations), and social responsiveness (anticipatory and preventive adaptation to social needs).126

Building on the conceptual framework proposed by Sethi, Carroll developed a model in 1979 that categorises corporate responsibility into four distinct areas, with the most important responsibility occupying the lowest position in the hierarchy. Carroll broadened the scope of CSR beyond traditional economic and legal considerations to include ethical and philanthropic responsibilities in response to growing concerns about ethical issues in business.127

In the past, companies were set up to provide goods and services and to make a profit. Economic responsibility can be defined as the fundamental obligation of companies to make a profit. This responsibility is considered to be the most fundamental and essential because the viability and sustainability of a business depends on its ability to make a profit and, therefore, on its economic responsibility.127

In addition to the pursuit of profit, companies have an obligation to comply with the laws and regulations that govern their activities. This is seen as an integral part of the social contract between business and society at large. Legal responsibility is a codified form of ethical behaviour, based on the principles of fair dealing as defined by the lawmakers. Although legal responsibility is presented as the next layer in the pyramid to illustrate its historical development, it is considered to be equal in importance to the economic responsibility, which is the fundamental characteristic of the free market economy.127

Ethical responsibility represents activities and practices that are expected or prohibited by society, even in the absence of legal regulation. It encompasses standards, norms, and expectations that are perceived as fair, just, and consistent with moral rights. In many cases, ethical principles and values take precedence over legislation and influence the formulation of laws. Ethical responsibility also includes adherence to new values and norms that are expected by society, even if they exceed the standards prescribed by law.39,127

At the top of Carroll’s CSR pyramid is philanthropic responsibility, which refers to a company’s voluntary efforts to contribute to the betterment of society. The term philanthropy is defined as the actions of companies that align with societal expectations of corporate citizenship.128 It includes active involvement in initiatives or programmes that promote well-being or positive social impact. Examples of philanthropy include making financial contributions or donating management time to artistic, educational, or community causes. Unlike ethical responsibility, which is expected to conform to ethical or moral standards, philanthropy is not necessarily perceived as a moral obligation. As a result, philanthropy is typically regarded as a voluntary undertaking on the part of companies. In this context, philanthropy is regarded as a less important than the other aspects of CSR and is frequently viewed as an additional, optional component.39,127

The higher the level of engagement that can be attributed to an organisation, the greater the potential to promote societal benefit, environmental stewardship, and value creation.39

In the context of academic discourse, CSR has emerged as a prominent area of study. The following section outlines the current research topics within this field. Despite the extensive research conducted thus far, there remain significant gaps in knowledge that require further investigation. This will be discussed in the following section.

6 Current state of CSR research

6.1 Positive and negative CSR

In Chapter 1, a variety of definitions pertaining to CSR were presented. A recent stream of research has expanded on this by pointing out that CSR has so far focused primarily on its positive aspects, hence the term positive CSR (PCSR). To be more precise, PCSR is defined as “the treatment of stakeholders in a manner that is ethical and socially responsible”129 (p. 220). However, this overlooks the fact that companies engage in unethical or socially irresponsible activities that have a detrimental impact on social welfare. Such irresponsible acts are defined as negative CSR (NCSR) activities.130 NCSR is a concept that can be defined as an overall absence of responsible actions within an organisational setting.131 According to Bird et al., ignoring NCSR activities portrays an incomplete picture of the financial consequences of a company’s CSR.132 Examples of NCSR practices may include instances where a supplier of goods or services engages in the use of prohibited chemical substances, the employment of child labour, bribery, or the illegal disposal of waste materials.130

The results of a quantitative study on PCSR and NCSR, published in 2020, suggest that organisations may be able to avoid certain consequences associated with NCSR. The returns, including the return on equity and the return on assets, may be influenced by NCSR. Consequently, it may be possible for an organisation to mitigate the impact of NCSR by increasing investments in less market-oriented assets. Alternatively, the NCSR effect in the CSP can be offset by investing in PCSR.130 This suggests that organisations should disseminate information about their socially responsible activities, while minimising the negative impact of their socially irresponsible operations. However, the latter is still receiving insufficient attention in the prevailing economic context.

6.2 Long-term effects of CSR implementation

The involvement of organisations in CSR can exert a beneficial influence on the economy, society and the environment over the long term. Investments in CSR with a focus on sustainability can lead to cost savings and competitive advantages at the economic level. Furthermore, the relationship with stakeholders, including customers, employees, and investors, can be enhanced, which may result in long-term loyalty and support.133 Social CSR initiatives have the potential to contribute to community development and to foster local trust. Consequently, this can result in a greater stability of the working environment, which is of particular importance in periods of shortage of skilled labour, and in turn has a positive impact on company profits. From an environmental standpoint, the implementation of sustainable CSR practices is of paramount importance for the reduction of the environmental footprint and the paving of the way for a more sustainable economy. The implementation of environmentally friendly measures can enhance the company’s image and appeal to environmentally conscious consumers, which can positively impact the company’s long-term competitiveness and align with global sustainability goals.133

Nevertheless, the long-term effects of CSR remain relatively unexplored in academic literature. while a considerable corpus of research has examined the immediate impact of CSR initiatives, there is a notable absence of studies that have focused on their long-term implications.133,134 This gap in the literature is significant as it limits our understanding of the sustainability of CSR initiatives and their enduring influence on a company’s reputation, financial performance, and social impact.135

6.3 Output and impact measurement of CSR implementation

The importance of measurement is emphasised by Harrington (1987), who states that “if you can’t measure something, you can’t understand it; if you can’t understand it, you can’t control it; if you can’t control it, you can’t improve it”136(p. 103). Nevertheless, the definition of what constitutes the impact of CSR initiatives is a complex one. In order to assess the impact of a carbon reduction programme, it is important to consider a range of relevant metrics.137 Such metrics may include the total amount of emissions saved, the number of people who stand to benefit from the programme, or the cost savings achieved The effective measurement of impact requires the adoption of robust metrics that are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART).138

Despite the existence of several proposed metrics for quantifying CSR activities, there is currently no consensus on a standardised measurement framework. The use of disparate metrics and methodologies by disparate organisations presents a significant challenge to the drawing of comparisons between results across diverse studies and industries. Furthermore, the extant metrics often fall short of capturing the full scope of CSR, with a predominant emphasis on tangible outcomes and a notable dearth of attention to intangible effects such as brand image enhancement or employee satisfaction. A pivotal challenge in this context is the lack of standardised data on CSR initiatives. This is compounded by the fact that companies often report their CSR activities in a manner that is not comparable across organisations, due to the differing methodologies employed in their reporting.134

Moreover, although the multi-dimensional nature of CSR implementation has been acknowledged by the majority of researchers, the conceptualisation and operationalisation of CSR implementation at a multi-dimensional level has not yet been achieved. It is therefore essential that future research consider the multi-dimensional nature of CSR implementation, employing a scientific approach that is not limited to a single level of analysis.139

6.4 Integrating CSR into the company’s core strategy

A survey of 766 CEOs conducted by the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) in 2010, prior to the implementation of reporting requirements, revealed that 93% of respondents believed that sustainability issues would be pivotal to the future success of their business.140 Additionally, 80% of respondents anticipated that sustainability would be fully integrated into their strategy within the next ten years.140,141

Porter and Kramer define strategic CSR as a business activity that aims to enhance both economic and social outcomes.142 They propose that a strategic CSR approach has a beneficial effect on society and investors alike.68

In order for CSR to become a strategic activity that adds value in different dimensions, it is essential that CSR is integrated with the company’s overall strategy. The integration of CSR with the fundamental business objectives of an organisation allows for the enhancement of social impact and the achievement of long-term success. This can be achieved by engaging with key stakeholders, integrating CSR into the organisational governance structures, developing a comprehensive strategy for CSR and maintaining transparent communication.143

The integration of CSR into business strategy presents a number of inherent difficulties. Financial constraints, the measurement of impact, the alignment of CSR with business goals, and the engagement of stakeholders can present obstacles along the way. While some companies appear to have successfully integrated CSR into their strategic planning, others regard it as a peripheral activity.144

Further research is required to ascertain the factors that facilitate or impede the integration of CSR into business strategies. In lieu of a disparate approach, a more integrated approach is required, whereby CSR is integrated into the company’s day-to-day activities, core competencies, shared understandings, and strategic decisions. This could provide valuable insights into how companies can leverage CSR to gain a competitive advantage.145

6.5 The role of social media in CSR performance

The utilisation of social media platforms for the dissemination of CSR initiatives is becoming increasingly advocated by both practitioners and academics. This is due to the fact that social media platforms facilitate transparency and may be considered a reliable medium.146 Furthermore, there is a growing number of individuals who are accessing messages shared on these channels. It is, however, important to consider the credibility of social media, given that it is also a hotspot for the proliferation of fake news.147 The dissemination of misinformation and false narratives is more prevalent on social media than in any other context. In light of this duality, companies are required to ensure that their CSR messages are transparent, precise, and substantiated by verifiable data. While social media can facilitate engagement and reach, it also necessitates vigilance in maintaining the integrity of the information shared.148

The two-way communication aspect of social media provides companies with the opportunity to disseminate information regarding their CSR activities, interact with stakeholders, and ultimately enhance their overall CSR performance. 149 Several companies have achieved notable success in utilising social media to improve their CSR performance. To illustrate, Patagonia’s Worn Wear campaign encourages customers to disseminate narratives about their previously owned Patagonia products on social media. The objective to promote awareness of the environmental impact of consumption and to reduce waste.150

The use of social media can serve as a model for the implementation of CSR communication strategies, facilitating greater levels of engagement and expression. By enabling the engagement of global stakeholders and corporate actors, it offers a useful platform for the creation of dialogue and the fostering of collaboration.151

Nevertheless, there is a robust debate surrounding the efficacy of utilising social media for the promotion of an organisation’s CSR endeavours and the enhancement of its brand, when weighed against the heightened risk of stakeholders employing social media for the monitoring, criticism, exposure and expression of scepticism regarding an organisation’s CSR activities.151 A particular concern is the risk of greenwashing, whereby organisations misrepresent their CSR activities in order to appear more socially responsible than they actually are.152 This can result in a loss of stakeholder confidence and a general scepticism towards the organisation. Moreover, the accelerated pace of social media can render it difficult for organisations to manage their CSR communications in an optimal manner, which may result in missteps and reputational damage. The ongoing challenge is to address these issues.151