Author: Isabella Joneck, 02 April, 2025

1 Introduction and Relevance

In recent years, sustainability has become one of the central topics of the global agenda. Moreover, research agrees that there is no sustainable development without sustainable organizations.1 Sustainable development is a task for society as a whole and requires the commitment and actions of all actors, including companies, to be successfully implemented. This is particularly evident when looking at global greenhouse gas emissions. Since 1988, just 100 companies have been responsible for 71% of total industrial greenhouse gas emissions.2 The relevance of organizations for sustainable development is therefore undisputed. Conversely, the relevance of sustainability for companies is also growing, as the study by the IBM Institute for Business Value (2022) shows.3 According to this study, 53% of organizations will consider sustainability to be one of their top priorities from 2024.3 This demonstrates that a significant proportion of companies have recognized the necessity to incorporate sustainability into their practices. In addition to perceiving sustainability as a moral imperative, there is a growing awareness in the corporate world that sustainability can also function as a long-term competitive advantage if it is effectively integrated.1 This is in contrast to the latest political developments in the USA with the re-election of Donald Trump as president and a nationalist-populist environmental and social policy that perceives sustainability activities as a redundant cost factor.4 However, the Omnibus regulation, which diminishes the scope of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), represents a setback for the advancement of a sustainable economy within the European context as well.5 It is therefore even more urgent that managers, in particular, are aware of their role and take responsibility for sustainability.4 Nevertheless, in this process, a considerable number of companies encounter difficulties in implementing sustainability practices due to their limited knowledge to do so.6 The notion of sustainable development, in its normative form, does not provide clear strategies, plans, and measures, particularly for corporate entities. As a result, a substantial number of guidelines, definitions, and measures have emerged, which contribute to the complexity of organizing and implementing sustainability.7

This leads to sustainability being a “field of high complexity” (p. 1)8, which is also attributable to the involvement of a large number of stakeholders and interests.8 In addition, the heterogeneity of organizations also poses challenges to transfer approaches from other companies.7 That is why, in the business world, sustainability is considered the “greatest challenge in organizational change management in today’s world” (p.1).8

One pivotal issue that emerges in particular is the organizational structure. According to Aghelie’s (2017) study, the business structure is identified as a significant barrier to engagement in sustainability.9 These findings are consistent with the conclusions of the study by Lewis et al. (2015), which identified a weak organizational structure as a hindering factor to sustainability integration in companies.10 Based on these findings, suitable organizational structures for sustainability can have a significant impact on the integration of sustainability in companies. The organizational structure can either promote or impede the advancement towards sustainability, depending on the presence of structural elements that are conducive or incompatible with this objective.11,12 Thus, research states that organizational structures that coordinate all elements of a company are necessary to support the development, transfer, and application of new knowledge and aspects for sustainability, and to create a suitable framework.13

In the context of this thesis, the subsequent research questions are addressed:

- What are organizational structures for sustainability and what is the current state of research?

- How can organizational structures for sustainability be successfully implemented in practice?

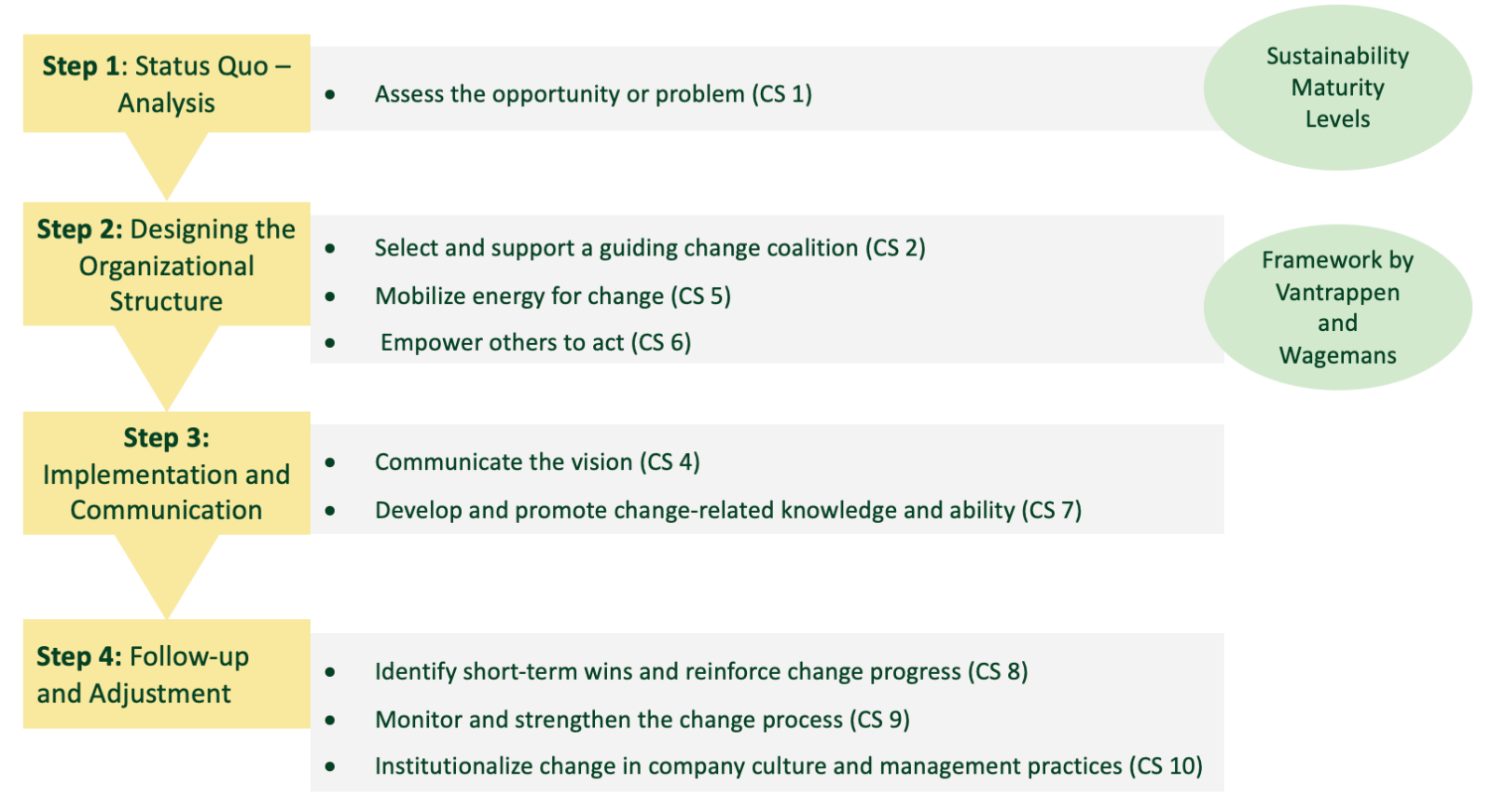

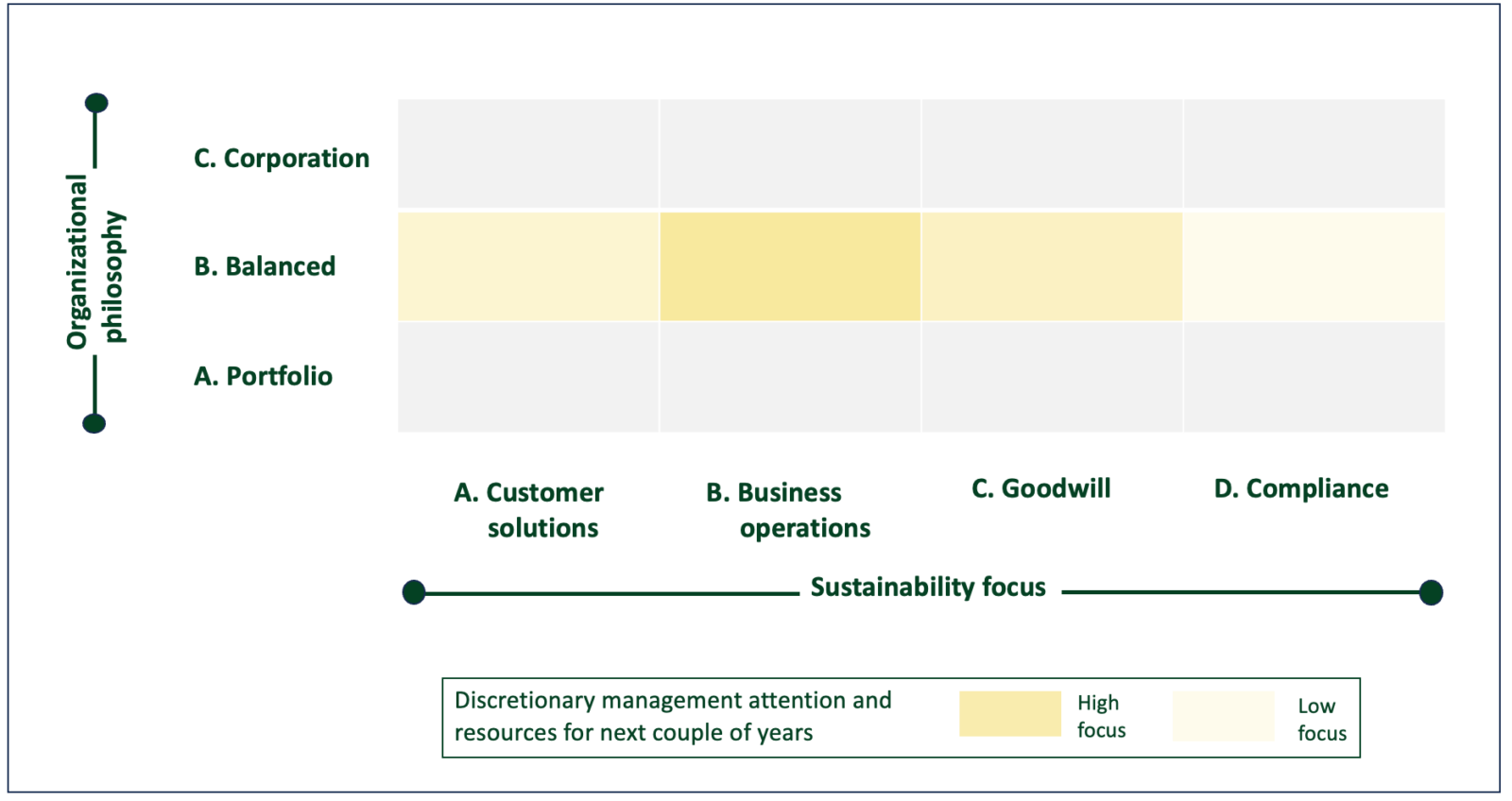

It should be noted that this work is limited to the consideration of business organizations. To answer the research questions, after the presentation of the applied method in this thesis in Chapter 2, the literature review is elaborated on the topic of organizational structures for sustainability. Chapter 3.1 offers a comprehensive overview of organizational structures in general, excluding the specific context of sustainability. The topic is defined, and characteristics and various organizational forms are presented. The subsequent Chapter 3.2 then explores organizational structures specifically for sustainability. The historical evolution of the topic in research and practice is presented first, followed by the current status of the dimensions and concrete structures for sustainability. Moreover, the connection between the selection of certain organizational structures for sustainability and the sustainability maturity level of the company is also discussed. The chapter concludes with an outlook for future research. Chapter 4 focuses on the practical implementation of organizational structures for sustainability. A four-step process, accompanied by frameworks and tools for implementation, is presented and underpinned by best-practice examples. It also discusses hindering and supporting factors for the implementation. The thesis concludes with a brief summary.

2 Basics of Organizational Structures

The following chapters outline the basic principles of organizational structures. Initially, the concept of organizational structures is defined, and characteristics and types are identified. This is followed by an embedding of the topic in the overarching concept of organizational design and a presentation of the interrelationship between organizational structure and strategy. It should be noted that the objective of this chapter is to provide an overview of organizational structures in general rather than focusing on organizational structures for sustainability in particular. The focus on sustainability will be further outlined in Chapter 2.2.

2.1 Definition of Organizational Structures

Organizational structures describe permanent regulations that assign tasks, competencies, and responsibilities to organizational units and combine them in an orderly and connected way.21

They define how an organization operates internally and adapts to changes in its environment. Latter is emphasized by Soderstrom and Weber (2020) as well, who state that “structures give shape to how organizations address new issues” (p.227).19 This is particularly relevant for the topic of sustainability as a ‘new issue’ for companies and shows the importance of organizational structures specifically for sustainability, which is further outlined in Chapter 2.2. Moreover, organizational structures represent a multidimensional construct of different factors. It provides a framework that determines, among other things, interactions, the exchange of information, and participation in decision-making processes within a company.12,22 Thus, organizational structures deal with “an organization’s internal pattern of relationships, authority, and communication” (p.282).22 In addition, the purpose of organizational structures is to facilitate decision-making processes, dealing with changes in the business environment, including environmental changes, and conflicts between units.23

2.2 Characteristics of Organizational Structures

The literature on organizational structures focuses on the following three main dimensions: centralization,formalization, and complexity.22,24

In addition to the three main dimensions, the literature also mentions hierarchy, specialization, and standardization as alternative characteristics of organizational structure. The origin of these structural dimensions can be traced back to organizational design theory and contingency theory.13

Moreover, the dimensions can be differentiated according to their focus. Specialization and complexity are concerned with the internal division of labor, whereas standardization and formalization are oriented toward processes. Centralization, on the other hand, is focused on the location of decision-making powers.25 It should be noted that the alternative dimensions are only described briefly due to lower relevance for the following chapters.

2.2.1 Centralization

Centralization describes the degree to which decision-making power is concentrated within an organization. A high degree of centralization is characterized by the fact that decision-making power is located in the upper management levels. This means that strategic and operational decisions are made by a few managers or a central authority.24 As mentioned above, centralization thus refers to the location of the authority to make decisions.22,25 By locating decision-making power in a central location, it can contribute to improving the coordination of activities and decisions in a company, on the one hand. On the other hand, centralization can increase the reaction time due to the small number of people having decision-making power.26

2.2.2 Formalization

Formalization is characterized by the use of explicit written policies, rules, procedures, and communications.25 These written frameworks guide decision-making, employee behavior, and working relationships within an organization.13,24

Although formalization is often regarded as a positive factor in terms of structure and stability, the literature states that formalization produces trade-offs as well.27 On the one hand, a high degree of formalization contributes to the reduction of role ambiguity since the distribution of tasks is clearly defined and written down. This is specifically relevant for organizations increasing in size and complexity. On the other hand, a high degree of formalization is seen critically as it is regarded as limiting creativity, personal initiative, and discretion.12,18,28

2.2.3 Complexity

Complexity as a structural element describes the degree of differentiation of a company. Thus, it provides insights into the interdependence or interrelationship between the distinct parts, functions, and subsystems that comprise an organization. It can be categorized into horizontal and vertical differentiation.12,13,22,24

Horizontal complexity refers to the number of departments within an organization and its linkage. Moreover, horizontal differentiation is related to the extent to which tasks are divided between departments and functions and their coordination and integration within different organizational units.12,13

Vertical complexity, according to Pérez-Valls et al. (2019), involves the number of hierarchical tiers and how they are connected.12

2.2.4 Hierarchy

Hierarchy is defined as the integration of positions within one explicit organizational structure. Each position or task is monitored and controlled by a higher authority.29

It can be classified into two categories: informal and formal hierarchy. The informal hierarchy is characterized by a system of dominance and subordination, which is person-related and results from social interaction. Moreover, informal hierarchy is consolidated, in particular through routinized behavior and repeated social processes.29

In contrast, formal hierarchy is a person-independent system in which roles and positions are clearly defined and delimited. The roles are linked by a top-down command and control system, and the social relationships within an organization are recognized only as hierarchical.29

2.2.5 Specialization

Specialization describes the extent to which a task is divided among different positions. This also means that specialization entails the repetition of certain tasks. On one hand, this can result in increased productivity. On the other hand, it can also lead to diminished job satisfaction due to the constant repetition.25

2.2.6 Standardization

Standardization describes the degree to which procedures are regulated.25

A procedure should be defined and specified in such a way that it does not require any assumptions about its use. All potential situations should be covered in the definition and specification of the procedure.30

2.3 Types of Organizational Structures

The topic of types of organizational structures is introduced by stating the most important terms and presenting relevant structuration principles followed by the description of various forms of organizational structure, including its characteristics and (dis-)advantages.

2.3.1 Terminology and Structuration Principles

A ‘job’ is defined as the smallest organizational unit that takes on clearly defined tasks or roles. An ‘instance’ is characterized as a unit with the authority to issue instructions and delegate tasks. In contrast to instances, ‘staff-/service units’ have no authority to issue instructions but are set up to prepare decisions for the instances. Lastly, ‘departments’ result from grouping several jobs in a hierarchical structure, which then can be connected to the main departments and divisions.31

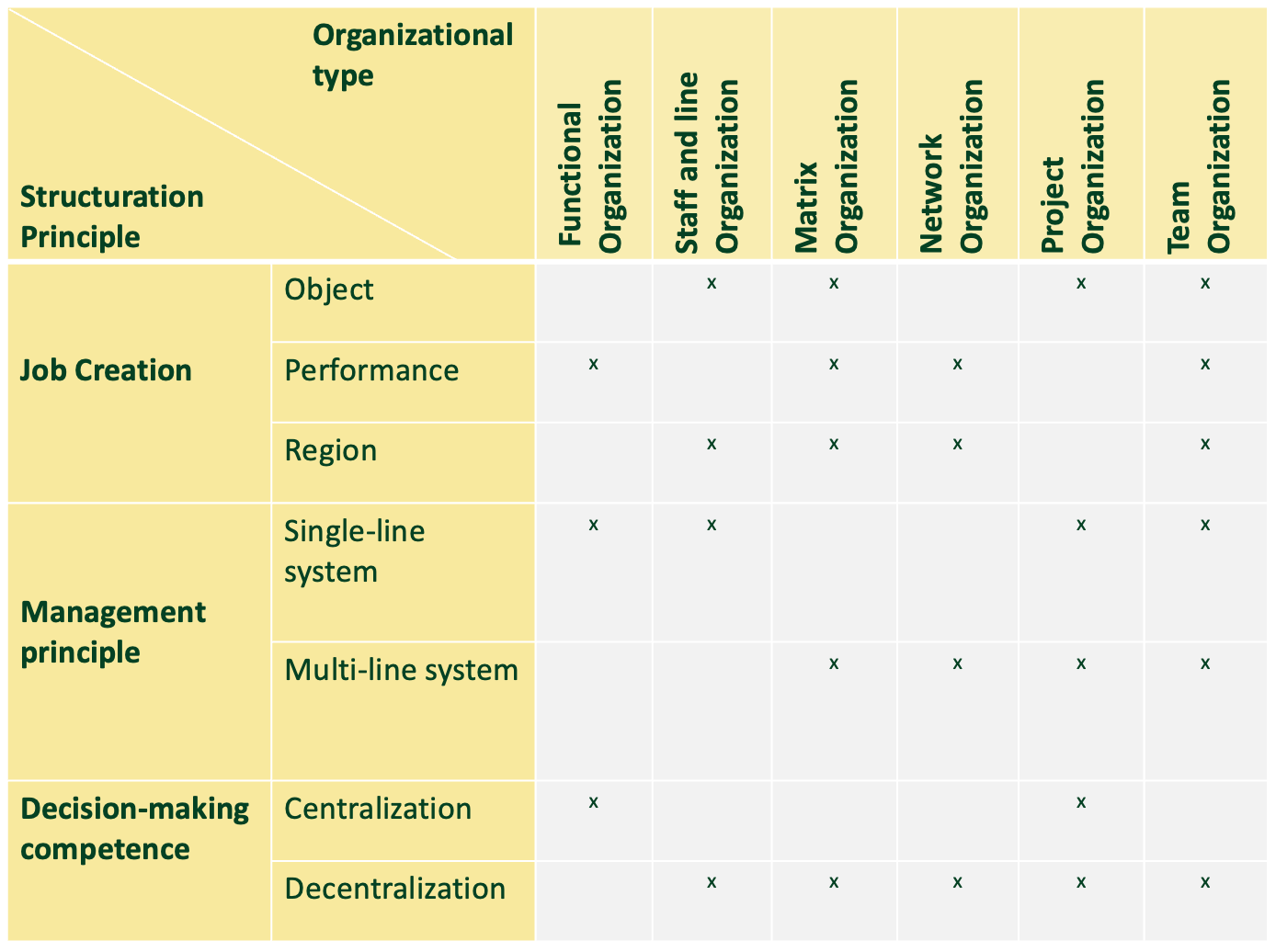

Although the structuration of these terms arises in practice primarily from a variety of company-specific circumstances, some types of organizational structures can be traced back to general structuring principles.32 The most widespread structuring principles and the resulting organizational types are described in the following:

- Principle of Job Creation

This principle aims to form an organization by distributing tasks to jobs. Moreover, it should optimize the relationship between jobs within the company as well as the relationship between the company and its environment. The job creation can be carried out according to the following characteristics:

- Job creation according to performance principle, e.g., functional structure

- Job creation according to object, e.g. divisional structure

- Job creation according to regions, projects, or customer groups, e.g., project structure

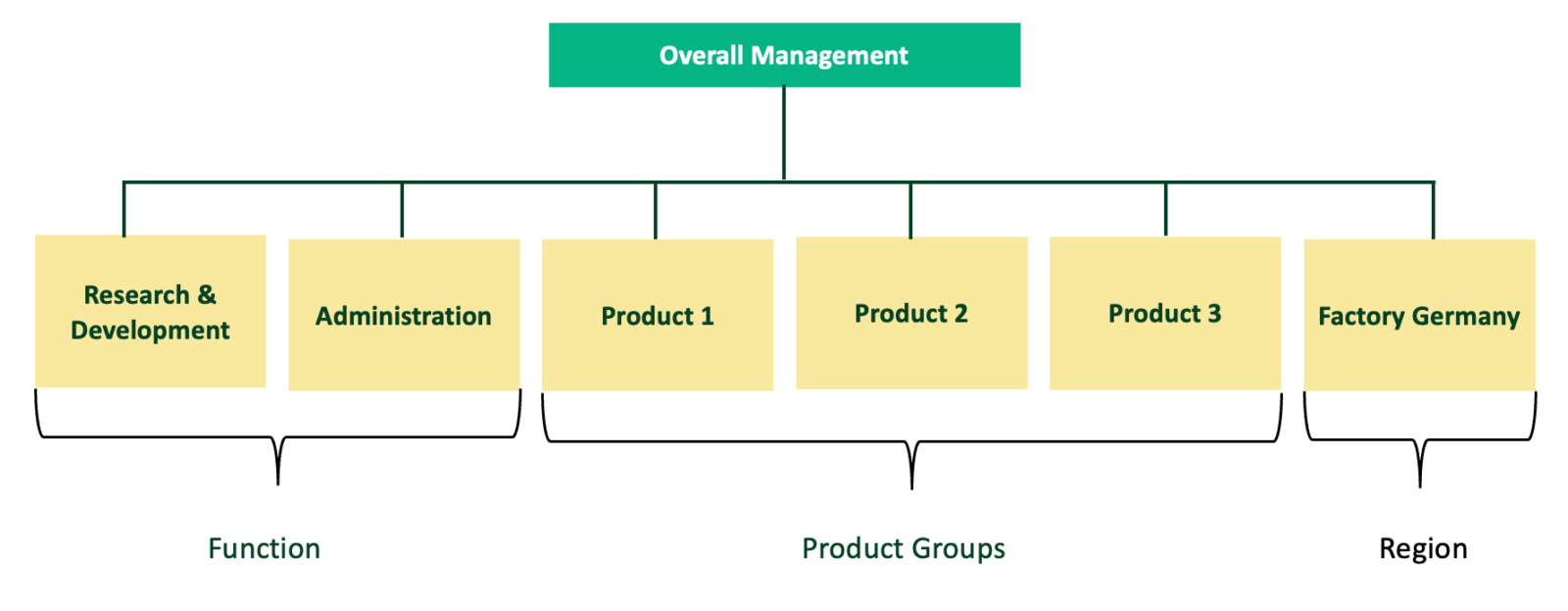

One important aspect to be noted is that, in theory, a characteristic should only relate to one hierarchical level. This means, for example, that the top level is structured according to performance and the second level according to the object principle. However, reality shows that job creation is structured according to different characteristics at the same management level. Figure 1 illustrates this fact, which arises due to historical development, the management style of the company, or the importance of jobs.32

- Management Principle

The management principle describes the communication relationship between employees and managers that arises from the division of work. The relationship is rooted in the fact that decisions must be ordered to be executed, and all information relevant to the decision must be reported. Hereby, a distinction can be made between single-line and multi-line systems. In a single-line system, each job is connected to only one higher instance it receives instructions from and communicates to. In a multi-line system, each job is subordinate to multiple higher-level instances.32

- Distribution of Decision-making Competence

This principle is concerned with the (de)centralization of decision-making power. In the case of centralization, decision-making tasks, and implementation tasks are divided between different jobs. However, this is more of a partial transfer of decision competence rather than an absolute separation of tasks. Decision decentralization, on the other hand, delegates decisions to hierarchically lower positions.32

The table 1 below provides a visual representation of the structuring principles that form the basis of the organizational structures presented in the following.

Furthermore, a distinction can be made between primary and secondary organizations. The primary organizations include the functional, divisional, and matrix organizations, which represent the basic structure of the company and handle regular, permanent tasks. The secondary organizations (project organizations, team organizations, network organizations) complement and support the primary organizations in the performance of special tasks that are not routine tasks.33

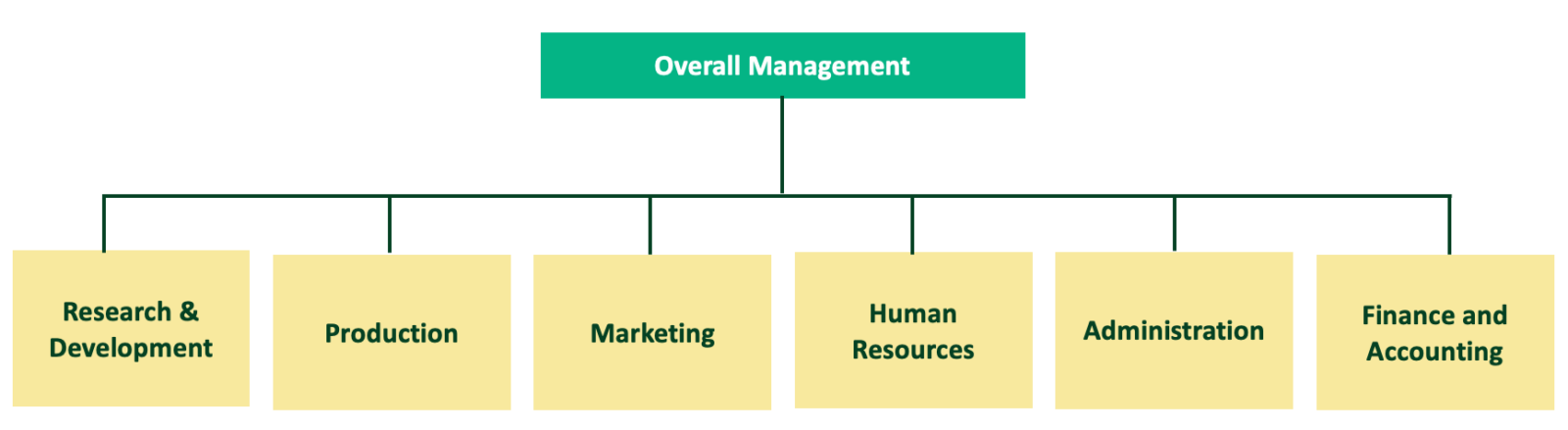

2.3.2 Functional Organization

The functional structure is characterized by a division of the second hierarchy level of the company into functional areas such as sales, development, and production as depicted in Figure 2. This means that similar activities are combined into one function, thus relying on the above-mentioned performance principle.32 In practice, this organizational structure is applied in companies with a limited business scope, a homogeneous product range, or a stable corporate environment, as with this organizational form, the company is not capable of coping with changes in the short or mid-term.31

The advantage of the functional structure is that productivity increases and greater efficiency can be achieved by combining the tasks and the resulting specialization of topics. In addition, the delineated functional areas prevent duplication of work, and specific and individual skills and knowledge can be considered more effectively.33

On the other hand, potential organizational interfaces between the functional areas result in increased communication and integration efforts. Moreover, the number of departments and tasks can lead to slower decision-making, which hinders the flexibility to react to changes. Another risk is that conflicts of interest between the individual areas can arise due to different orientations, resulting in overburdening the company management.32,33 That’s why functional single-line systems are rare in practice or only applied by small companies with few employees.32

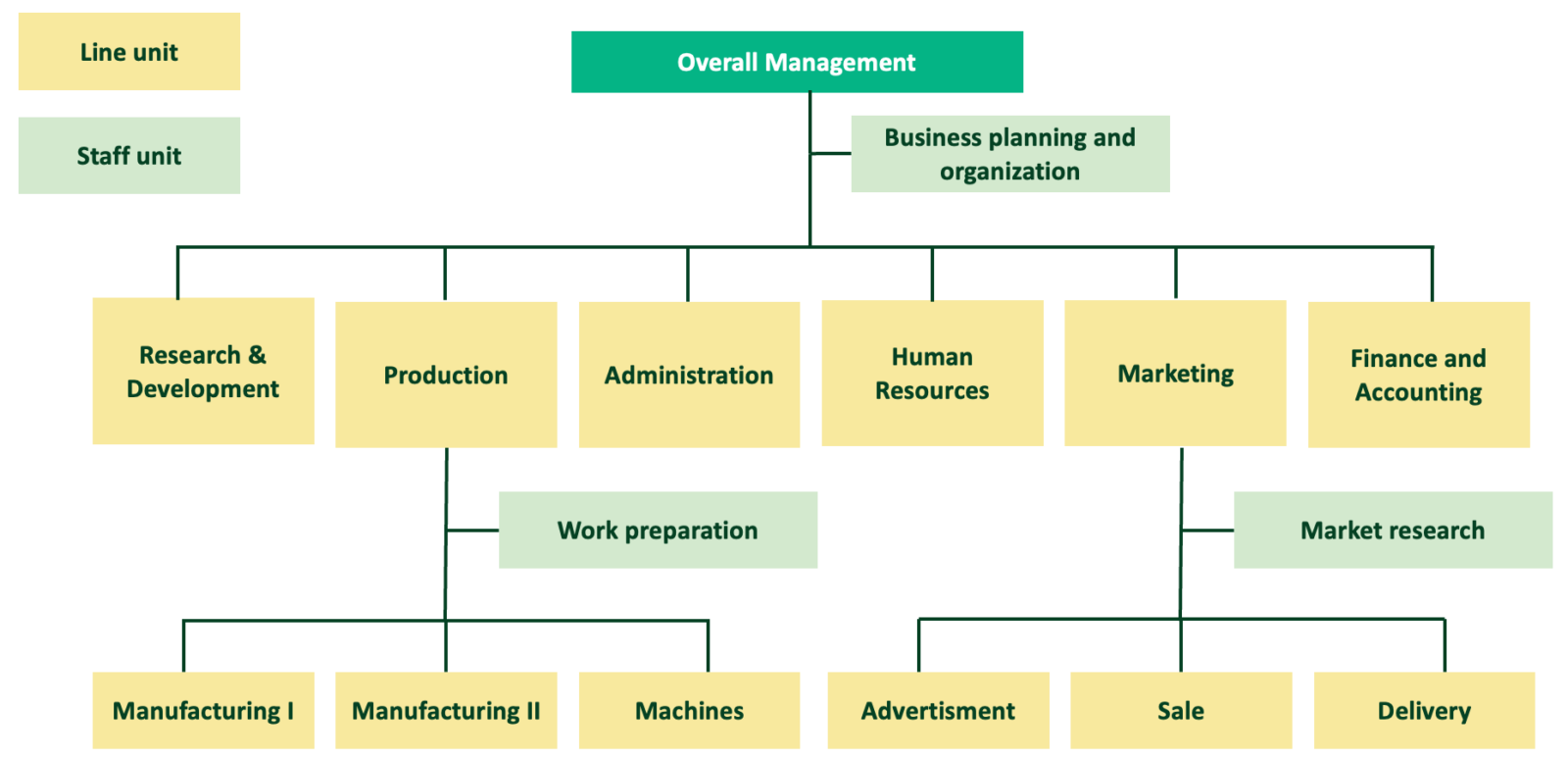

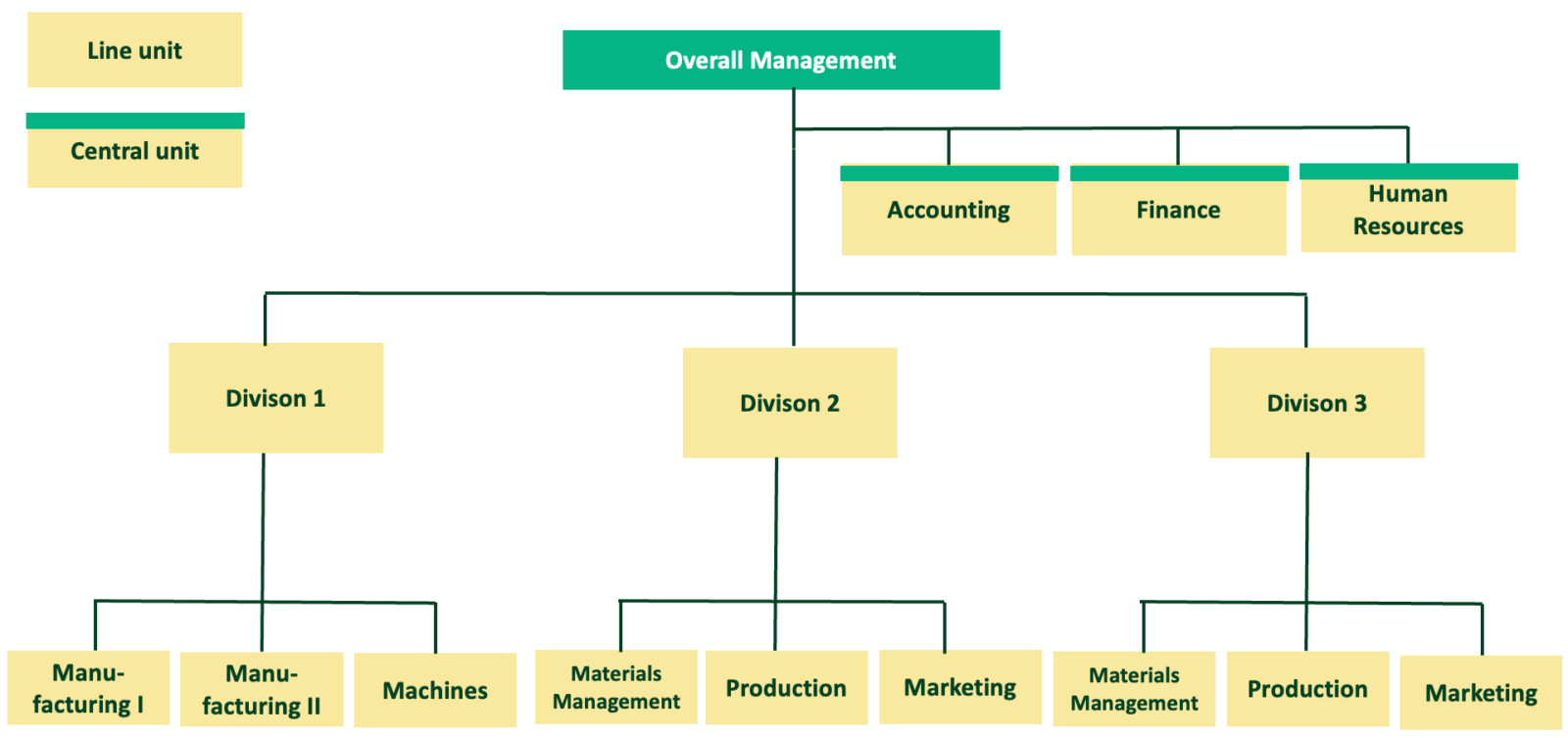

2.3.3 Line-and-staff Organization

As illustrated in Figure 3, line-and-staff organization can be defined as a form of functional organization that has been extended by one or more staff units.31 They emerge as a response to the aforementioned disadvantages of functional structures and the need to alleviate the instances by introducing staff units.32 In addition to the alleviation of the instances, decisions can be prepared more carefully within a line-and-staff organization due to the supporting activities of the staff units.

Nevertheless, the line-and-staff organization also includes various disadvantages, such as the risk of arising conflicts, as the preparation of decisions, the actual decision-making, and its implementation are separated. Moreover, competition can emerge between staff and the instances, as the staff units have no authority to issue instructions but possess extensive knowledge about the topics.32

2.3.4 Divisional Organization

In the divisional structure, the company as a whole is divided into different divisions by applying the object principle as described above.32 The divisional organization intends to combine identical or similar objects, i.e., product/customer groups, regions, markets, or business units, into autonomous and homogeneous divisions. Thus, the divisional organization is influenced by the heterogeneity of the production and/or sales program, the management style, i.e., the extent to which tasks, competencies, and responsibilities are delegated, as well as the size and geographical distribution of the company.32

As Figure 4 shows, the organizational structure below the divisional level is then often based on functional criteria. However, in large companies, multilevel divisionalization is also common. That means that job creation according to objects is also used below the second level of hierarchy.31

As with all forms of organization, divisional structure also has its advantages and disadvantages. Favorable for organizations is, for example, the division that results in reducing the complex relationship within a company and with its environment. Additionally, decisions can be made more quickly thanks to shorter communication channels, and the company gains flexibility through the structure.

In contrast, the division into smaller units can lead to coordination problems and increased administrative costs, as well as a greater need for qualified managers. Another disadvantage is the potential risk that the individual divisions work against each other rather than together, resulting in a failure to exploit synergy effects.31,33

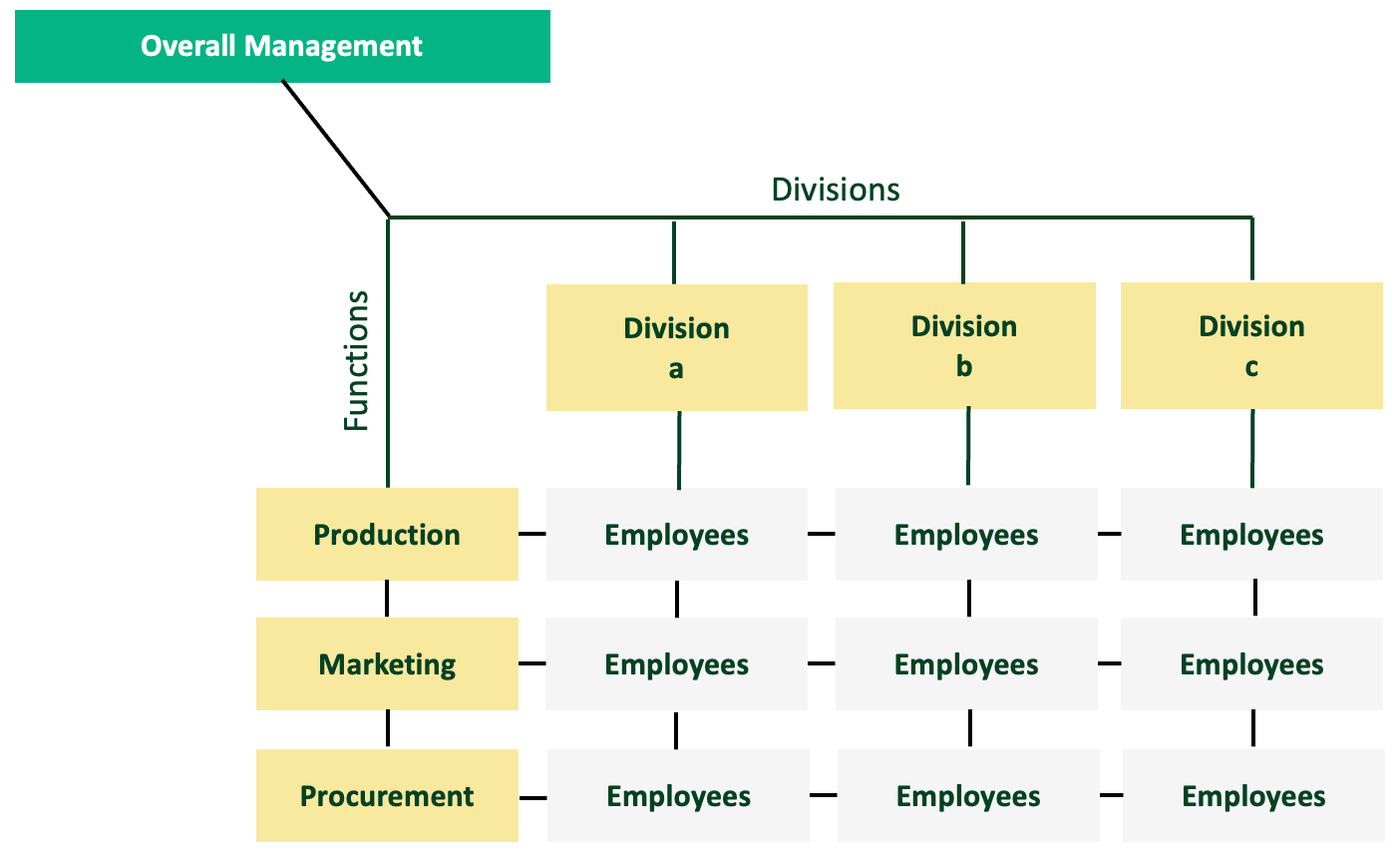

2.3.5 Matrix Organization

The matrix structure is a form of multi-line organization. The characteristic of a matrix structure is that the management function is divided into two or more dimensions (products, functions, regions, projects) as shown in Figure 5. The dimensions are independent and equal, which means in the event of conflicts, there is no dimension given more power than the other. In addition, the employees also have two or more relationships of authority, i.e., they are subject to a horizontal and vertical area of responsibility.32

The challenge associated with the matrix organization is the clear demarcation of tasks, competencies, and responsibilities at the management levels. This also leads to an increased need for communication and information, as well as more complex decision-making. In addition, employees may experience confusion and competence problems due to the fact that they are subject to two areas of responsibility.33

Conversely, favorable aspects of the matrix organization are the establishment of interdisciplinary cooperation between various company divisions, the promotion of teamwork, and greater capacity for innovation as well as greater participation in problem-solving processes. Moreover, tasks can be considered and processed more comprehensively by specialists.32

2.3.6 Network Organization

Network organizations are made up of different actors, such as individuals, groups, and organizations. The network is linked by a commonly shared goal and service or product to which each member contributes its know-how.32

A distinction can be made between an internal (intra-organizational) network, which connects organizational units within the company, and an external (inter-organizational) network.33 The latter is gaining importance in practice. It involves cooperation with other companies and aims at utilizing synergy effects, i.e., each company concentrates on the part of the value chain in which it has the greatest expertise.32

External networks are often used when companies operate in volatile markets, face a substantial market risk, or lack expertise and capital. In this case, cooperation in networks can lead to a reduction in development costs, a distribution of risk, and the accumulation of expertise and capital. Moreover, the structure fosters flexibility through the formation of networks for specific projects.17 Nevertheless, the network structure also creates a dependency on the quality and reliability of the network partner, as well as an increased coordination effort, resulting in potential costs and time losses.33Thus, the prerequisite for the success of such a structure is, above all, trust and suitable information and communication tools.32

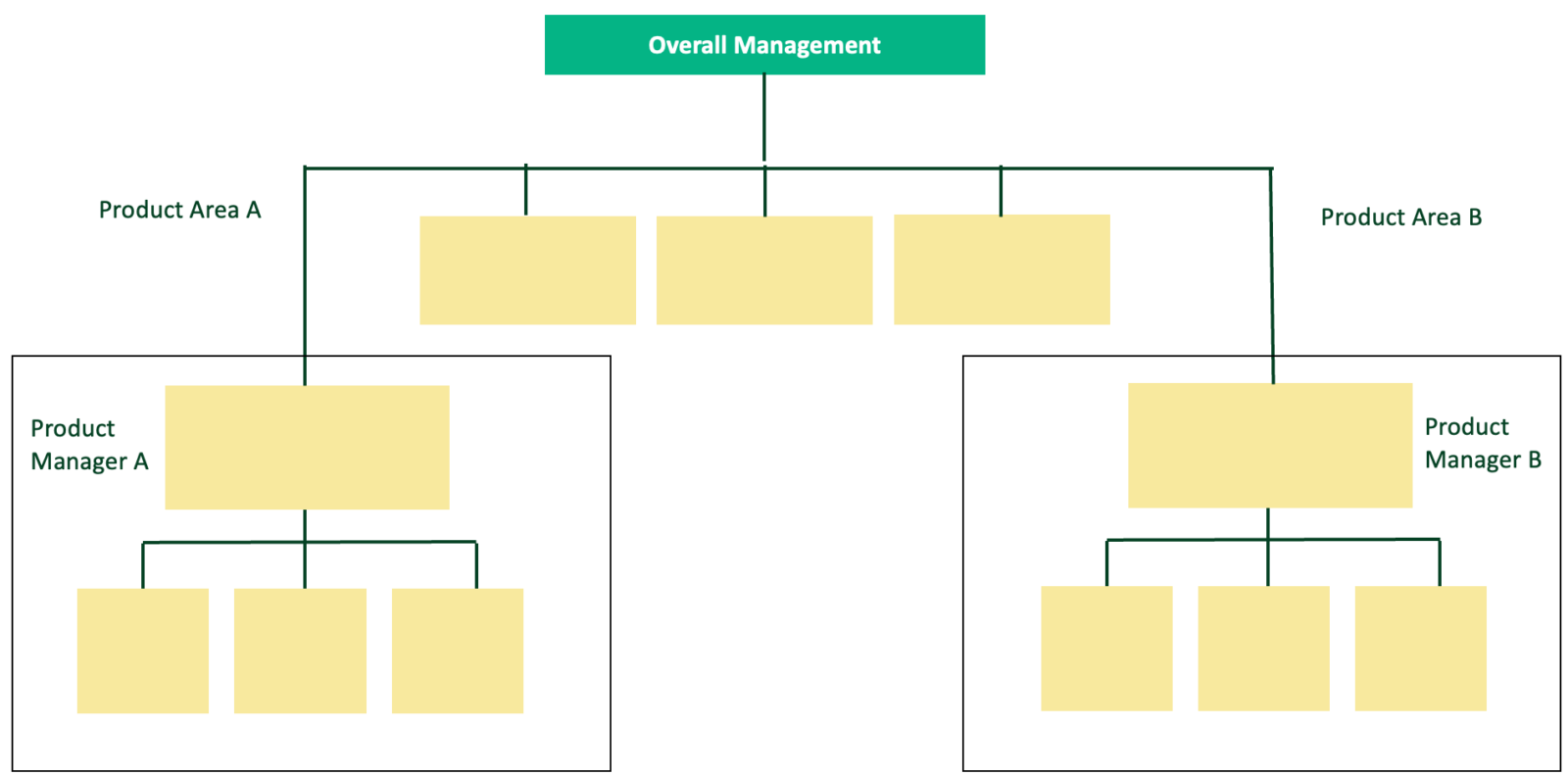

2.3.7 Project Organization

Project organizations, as shown in Figure 6 are established for the execution of projects and are exclusively responsible for fulfilling project tasks. A distinction can be made between simple, staff, and matrix project organizations (see previous descriptions of staff and matrix structures).33 These forms vary in the degree to which they are independent of the main organization and the autonomy of their resources.32

On one hand, these structures facilitate focusing on specific objectives, promote flexibility, and accelerate decision-making. On the other hand, project organizations pose challenges as well, including resource conflicts, communication skills, and potential instability through the limited existence of the project structure.32

2.3.8 Team Organization

Team organizations consist of groups of people who work together and autonomously on a task.17 These teams can function as an addition to the existing organizational structure or as a constituent element, which means that the organizational structure is comprised exclusively of teams. An additional team organization is especially suitable for complex projects that affect several areas of a company and require different knowledge. An example of such a project could be the sustainability implementation, which is outlined in more depth in the following chapter. This form of organizational structure is favorable as it enables the utilization of synergy effects by integrating information and knowledge of all employees. Furthermore, it increases the flexibility of the company and an agile working method. In contrast, this structure demands more time and the challenge of delineating responsibilities and competencies.32

2.4 Classification in Organizational Design and Delimitation to Strategy

In order to gain a greater understanding of organizational structures and their orientation, organizational structures are classified in the overarching concept of organizational design. Particular attention is given to the relationship between strategy and structure.

2.4.1 Organizational Design

According to van Bree (2021), organizational structures can be seen as a part of organizational design, the latter being defined as a comprehensive approach to integrating all aspects of an organization to fulfill its strategic vision.34Alongside processes and roles, structures are key elements addressed by organizational design. The primary interest here is how organizations can be designed to improve their performance.34

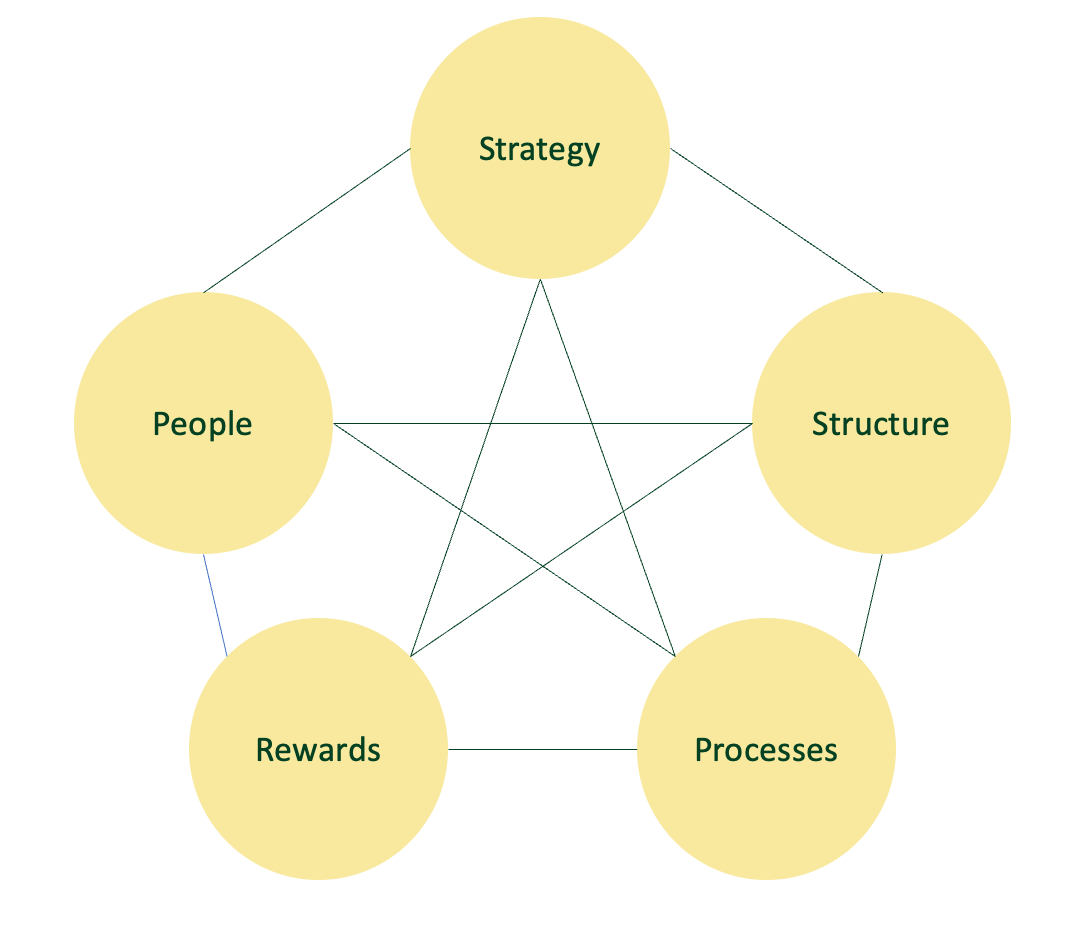

The Star Model, proposed by Jay R. Galbraith (2011), conceptualizes organizational structures as a component of a broader framework for organizational design as well. The model, as depicted in Figure 7 encompasses the five core design elements of strategy, structure, processes, rewards, and people, emphasizing the interconnection of these elements and the necessity of achieving a harmonious alignment to optimize an organization’s effectiveness and performance. In the context of organizational structure, this implies that it must be aligned with the other elements of the model and the specific strategic needs of the company to ensure success. The relationship between strategy and structure, in particular, has been a subject of extensive discussion in the extant literature.35

2.4.2 Strategy vs. Structure

In literature, two opposing perspectives have emerged regarding the direction of the relationship between strategy and structure. The classical school follows the lemma ‘structure follows strategy’. As a result, strategy is seen as a top-down activity on the basis of which the structure should be developed and adapted.16 In this context, strategy serves as the primary driver of organizational decisions, while structure serves to implement strategic goals. This principle is also widespread in the business world: First, define the strategy, then design or structure the organization accordingly.36

In contrast, a growing body of literature argues that structure has a major impact on strategy, thus following the lemma ‘strategy follows structure’. This means that the structure provides the framework that influences and significantly shapes the decision-making process and strategy of an organization.37,38 The view states that structure within a company affects not only the implementation of existing strategies but also the development of new strategies. This is particularly relevant in complex, process-oriented environments, where structure facilitates the emergence of new strategies.39

Despite the opposing views on the relationship between strategy and structure, the literature agrees on the existence of a significant relationship between these concepts.16 Furthermore, both perspectives lead to the same conclusion, namely that “a mismatch between strategy and structure will lead to inefficiency in all cases” (p.162).40

3 Organizational Structures for Sustainability

This chapter lays its focus on sustainability, i.e., it first provides an overview of the historical development of sustainability implementation in the structure of organizations from a scientific and practical perspective. Afterward, the dimensions and the organizational structures for sustainability itself and its trade-offs are presented. The chapter concludes by stating the evolution of the use of organizational structures for sustainability and an outlook for future research.

3.1 Historical Development in Science and Practice

At the beginning of the 1990s, the first publications on environmental management highlighted the importance of organizational structures to support environmental protection measures.41,42,43,44,45 The significance of organizational structures has grown, as they have been identified, among other things, as a competitive advantage.46 However, the relationship between organizational structures and environmental management remained relatively under-researched.17 In addition to the acknowledgment that organizational structures play an important role in sustainability implementation and should be more in the focus of research, it has been recognized that the prevailing structures during that period posed significant impediments to sustainability47,48,49 and promoted the maintenance of the status quo.12 Three primary reasons for this obstacle to corporate sustainability have been identified in the extant literature.47,48,49 These reasons were particularly prevalent in traditional, hierarchical, and centralized companies, which dominated practice at this time.17

- Isolated Information Systems

Firstly, traditional hierarchical and centralized organizations lacked mechanisms for collecting and transferring ecologically relevant information within the company. For instance, specialized departments or employees capable of recording, processing, and disseminating information regarding sustainability issues were absent. This resulted in a low implementation of environmental management within the company.50

- Dynamic Conservatism

The second reason is known as dynamic conservatism, meaning that new theories and approaches are perceived as a threat due to their potential to disrupt the existing corporate order.51 As a result, the entrenched routines hindered the adoption of innovations, new structures, and strategies that are essential for sustainability.45

- Limited Stakeholder Involvement

The final reason identified for organizational structures hindering sustainability was selective stakeholder engagement. Companies prioritized engagement with shareholders and board members while neglecting other crucial interest groups, such as employees and environmental organizations, which are pivotal for sustainability efforts.52 As with the previous reason, the demands of the marginalized stakeholders were perceived as a threat to company performance and, therefore, disregarded. This pattern of stakeholder exclusion was found to hinder the development of sustainability initiatives within companies.53

As a result of recognizing these impediments, the need for new organizational forms to promote sustainability emerged. Consequently, research at that time proposed alternative, more flexible, and decentralized organizational structures, including network organizations (see Chapter 2.3.7, ‘Network Organizations’), virtual organizations (see Chapter 2.3.9, ‘Team Organizations’), and communities of practice. The latter is based on informal networks of experts who share their knowledge and experience to develop joint solutions to sustainability challenges.17

During the 2000s, the increasing complexity of organizational structures, among other factors, was driven by mergers and the expansion of business activities. This led to a further neglect of research on appropriate organizational structures in general and specifically for sustainability.54 Nevertheless, the need for research in this domain and the recognition of its significance for practical implementation remained, as a study by McKinsey & Company in 2007 underscores. According to the study, corporate failures can be traced back to organizational design. Unsuitable organizational structures prevented organizations from adapting to trends such as globalization and sustainability and from developing cross-product/national capabilities. The authors emphasize that organizational design, which organizational structures are a component of, is imperative for effectively navigating opportunities and challenges posed by the 21st century.55

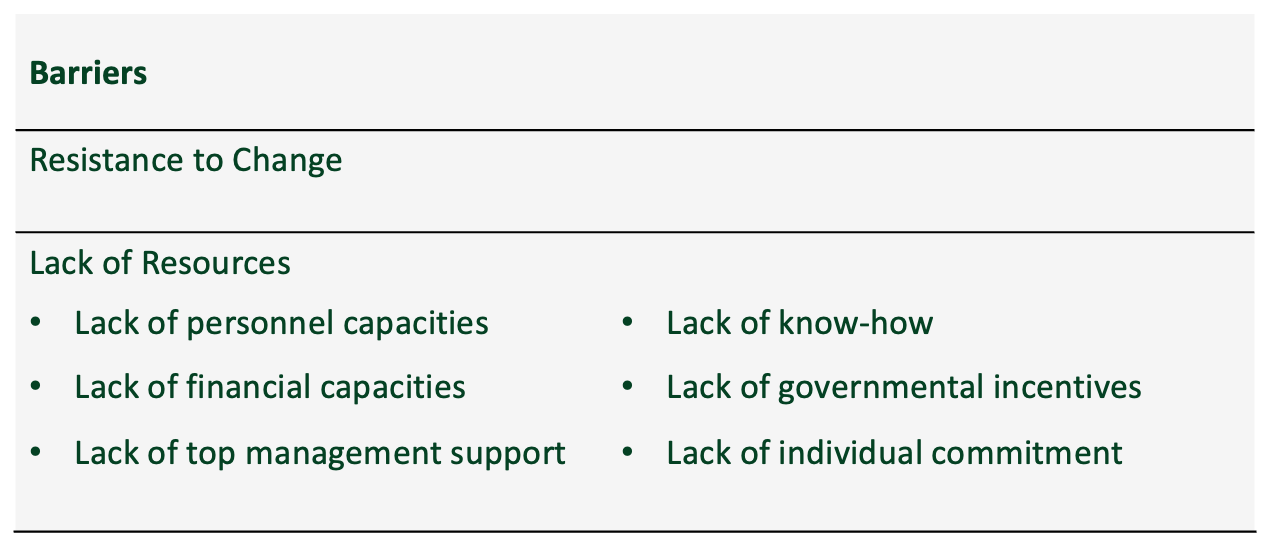

In practice, companies’ engagement with sustainability has focused rather on the integration into corporate strategy than on corporate structure. In the 1990s, companies attempted to manage ecological aspects systematically with environmental management systems such as ISO 140001, which emerged in 1996, creating a basis for structured approaches to environmental issues within organizations.56 Furthermore, at the beginning of the 21st century, the publication of the EU ‘Promoting a European Framework for Corporate Social Responsibility’ (2001), has led to a stronger focus on the topic in organizations. Nevertheless, it could be observed as before that the evolution was carried out more on a strategic than on a structural level by developing corporate social responsibility strategies that integrate social and ethical considerations into corporate management.57 In the following years, regulatory measures, such as the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (2014) and the entry into force of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (2023), have further challenged companies to actively address sustainability.58 The results of the Bertelsmann Foundation’s ‘Sustainability Transformation Monitor 2023’ show that sustainability is becoming increasingly important and present in the economy and how it is structured in companies. The study indicates that the responsibility for sustainability (measures) in the real economy is anchored in the board of directors at nearly 58% of companies, while 41% have dedicated sustainability departments. Moreover, the study identified that in addition to resources, the lack of competencies for implementation within the company is the greatest challenge to corporate sustainability.59 This underlines the acceleration of integration of sustainability practices into daily operations and the question of which structures suit sustainability best. As a result, it states the necessity for research on suitable organizational structures for sustainability. However, current research is “more concerned with the process of structuring than the selection and effectiveness of particular structures” (p.227).19

Recent findings on organizational structures for sustainability are reviewed in the following chapters.

3.2 Dimensions of Organizational Structures for Sustainability and its Trade-offs

This chapter provides a comprehensive analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of the three main dimensions of organizational structure – namely, formalization, complexity, and centralization – in the context of sustainability.

3.2.1 Formalization

The role of formalization concerning sustainability implementation in companies is characterized by contradictory arguments in the literature.12 The lack of clarity about the importance of formalization is accompanied by the complex task of finding the right degree of the dimension.18 The advantages of this structural dimension for sustainability are examined below.

In highly formalized organizations, the process of documenting procedures and guidelines establishes a structured foundation and a roadmap for addressing sustainability challenges. In addition, it facilitates the collection and distribution of knowledge on sustainability, ensuring its consistent application by all employees.12 Integrated management systems (IMS), such as the ISO 14001 standard for environmental management systems, are also guided by this logic. The implementation of IMS fosters the integration of sustainability within corporate entities through a systematic approach, comprising defined processes, procedures, evaluations, and objectives. This underscores the efficacy of formalization in enhancing sustainability integration.60 Moreover, the establishment of clear processes, rules, and standards prevents organizations from becoming disorderly.61

Furthermore, a high degree of formalization can increase the efficiency and effectiveness of business operations, particularly in routine tasks such as compliance with environmental regulations, documentation of CO2-emissions, or conducting sustainability training for employees.12 The knowledge that already exists in the company, particularly on how to deal with environmental issues, can be transferred to employees more easily through rules and standards. As a result, errors in the execution and the need to accumulate the same knowledge repeatedly are eliminated, thereby enhancing effectiveness and efficiency. Moreover, formalized control and reporting processes ensure that all employees and departments adhere to the company´s sustainability goals, fostering a comprehensive commitment to sustainability integration across the organization.12

However, it should be noted that formalization does present certain disadvantages for sustainability as well. An excessive degree of formalization limits the decision-making options62 and the flexibility of corporate structures to react appropriately to unforeseen events.63 This is particularly problematic for the implementation of sustainability, which requires a high degree of employee participation and the integration and creation of new knowledge. Prescribed rules and processes would inhibit the acquisition and application of new knowledge and thus innovation. This suggests that a less formalized corporate structure is favorable for sustainability.12

Especially for non-routine tasks, such as new or unique sustainability challenges, fixed processes often impede the solution to a problem as these challenges frequently require expertise that extends beyond the knowledge written down in processes and guidelines. A high degree of formalization has been shown to hinder the development of knowledge and creativity in problem-solving, thereby impeding the integration of sustainability aspects and the resolution of sustainability challenges.12 Conversely, a lower degree of formalization can foster the organic emergence of sustainability initiatives arising from non-formalized sources.19

Overall, it can be posited that a balance must be struck between formalization and flexibility to embed sustainability into the core of the organization.19 The most significant challenge for companies will be to identify the individual, optimal level of formalization.18

3.2.2 Complexity

Complexity as a structural element plays a central role in the design of sustainability in companies, as it significantly shapes a company´s communication processes.

Vertical Complexity

Vertical complexity, defined as the number of hierarchical levels in a company12 and its degree (high, low), influences the implementation of sustainability measures as follows.

A high degree of vertical complexity, i.e., a substantial number of hierarchical levels, impedes employee participation in decision-making processes and the dissemination of relevant information regarding sustainability. Given the necessity of an interdisciplinary approach and the exchange of knowledge, experience, and information for effective sustainability integration, high vertical complexity has a negative effect on the holistic and effective integration of sustainability measures. The coordination of substantially many hierarchical levels hinders the decision-making and active participation of employees.64

In contrast, low vertical complexity, i.e., flat corporate structure, promotes the development and maintenance of internal communication channels. This, in turn, facilitates the exchange and utilization of information, which supports employee communication and participation in sustainability decisions. Consequently, low vertical complexity has a positive effect on the implementation of corporate sustainability initiatives.12,52

Horizontal Complexity

Horizontal complexity describes the division of tasks within an organization and its units and functions.12

Accordingly, a high degree of horizontal complexity increases the number of departments that are engaged in working on a given problem, and thus also the diversity of perspectives. This can promote innovative and comprehensive solutions.12 Expertise from several departments can be particularly advantageous in the area of environmental sustainability, which often requires technical knowledge. This is due to the fact that a high level of horizontal complexity means that more departments are working on sustainability issues, and thus, extensive knowledge on sustainability topics can be accumulated.12 Soderstrom and Weber (2020) also conclude in their study that participation and exchange between different departments strengthen employees’ commitment to sustainability, which is an important prerequisite for successful sustainability integration. The results of the study show that successful sustainability measures often result from interdisciplinary interaction between employees.19

Conversely, a high degree of coordination efforts among departments can impede the implementation of sustainability initiatives. In addition, fragmentation can occur as a result of different working methods or target agreements, which hinders collective action and the integration of sustainability measures.12

Nevertheless, low horizontal complexity provides certain advantages for corporate sustainability. The collaborative efforts of a limited number of departments can evolve into establishing specialized units that possess profound expertise for addressing sustainability challenges. Furthermore, the coordination effort between the departments is reduced.12

It can, therefore, be seen that akin to the other two core dimensions of organization structure, literature formulates the advantages and disadvantages of implementing sustainability regarding complexity. It is, therefore, crucial for companies to identify a balance between these characteristics in order to pursue sustainability goals effectively.

3.2.3 Centralization

The degree of centralization can also have various effects on the implementation of sustainability.

In a centralized organizational structure, decisions are made exclusively by top management. Thus, only a few employees are empowered to make decisions, resulting in a slower and more bureaucratic decision-making process. This is accompanied by increased cognitive demands on the management, as complex sustainability issues must be understood and implemented even though the necessary specific knowledge is not available. For sustainability initiatives, in particular, it is noted that only higher positions can initiate them. As a result, the employees are marginalized in the sustainability process, and issues and opportunities pertaining to sustainability are more rapidly overlooked if only a select few have the authority to deal with it.12

In a decentralized structure, on the other hand, the decision-making process is often facilitated by the availability of expertise from multiple departments, leading to enhanced efficiency. The implementation and use of integrated management systems, or the modification of processes, for instance, often require specialist knowledge that the top management lacks.65 A significant aspect that has gained attention in the literature is the role of middle management and the involvement of employees in decision-making processes as key factors for the successful integration of sustainability.19,66 Empirical evidence indicates that the success of environmental initiatives within a company is contingent on the involvement and commitment of employees.67 A primary reason for this is that employees outside of upper management are in closer proximity to the sources of sustainability challenges (e.g., generation of CO2-emissions in production, social equality). This enables a more comprehensive understanding of measures for the sustainable conversion of the company.16 A decentralized structure facilitates this by promoting exchange and social interaction24and placing more decision-making power in the middle management of a company.12

Moreover, decentralization fosters the role of ‘sustainability change agents’. This term refers to individuals who initiate, promote, or implement change towards sustainability.68 As with the function of so called ‘power promoter,’ these agents have the capacity to overcome willingness burdens during the innovation process. According to the study by Kiesnere and Baumgartner (2019), these agents are indispensable for integrating sustainability at the strategic and normative levels.1The extant literature demonstrates that successful sustainability efforts are frequently the consequence of the involvement and participation of employees from diverse levels, as well as interactions between them. This confirms the advantages of decentralized structures for sustainability implementation.19

3.2.4 Interrelationship between Centralization and Complexity

A further finding in the literature is the interrelationship between centralization and vertical complexity, which states that the positive effects of decentralization can be impaired by a high degree of vertical complexity. This suggests that while decentralized decision-making can encourage the involvement of various stakeholders, a high degree of vertical complexity, i.e., numerous hierarchical levels, can impede the integration of knowledge from other functional areas into the decision-making process. This, in turn, results in a weaker and less effective implementation of sustainability efforts. The findings of the study by Pérez-Valls et al. (2019) indicate that the flatter the structure, the more substantial the impact of decentralization on sustainability integration. Consequently, it is imperative to consider complexity and decentralization parallel to ensure the most efficacious implementation of sustainability.12

Overall, it can be postulated that the implementation of sustainability in companies can be promoted through a careful balance of the main dimensions of the organizational structure. Moderate formalization can enhance efficiency and effectiveness through clear processes and knowledge management; however, it must not impede innovation and flexibility. Decentralized structures combined with vertical simplicity actively engage employees and support the positive effect of sustainability change agents and power promoters. The literature further demonstrates that flat, participative structures are particularly effective in implementing sustainability goals, while well-coordinated complexity increases knowledge performance. It is therefore evident that companies must create a dynamic, participative, and knowledge-based organizational structure that combines flexibility and efficiency to effectively embed sustainability in the company.

3.3 Organizational Structures for Sustainability and its Trade-offs

The academic literature on organizational structures for sustainability does not introduce new organizational forms but rather applies established structures to sustainability, as discussed in Chapter 2.2. The prevailing consensus in the literature is that no universally applicable organizational structure for sustainability exists and that different structures may be appropriate for a company at different times, for different tasks, and under different conditions.6 In the following sections, the findings of research on the transfer of traditional organizational structures in the context of sustainability and its trade-offs are introduced.

3.3.1 Functional Organization

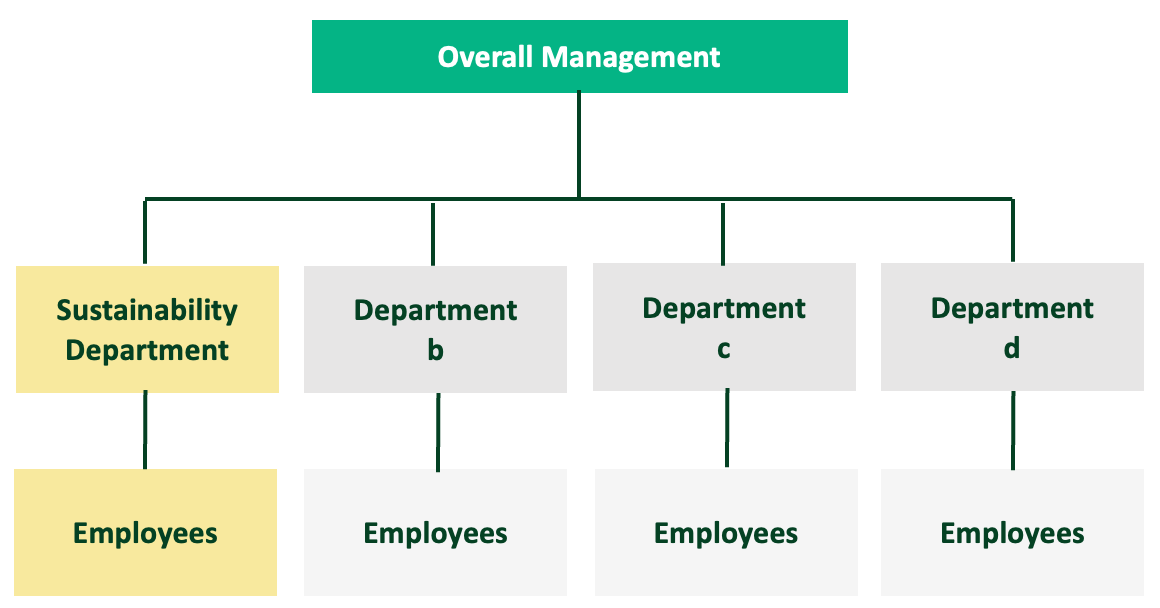

The establishment of a distinct sustainability department within the framework of a functional organizational structure as shown in Figure 8 is frequently motivated by the assignment of complex tasks to sustainability and, thus, the need to create a separate department to manage these responsibilities.69

A sustainability department is advantageous as it can be easily integrated into the organizational structure. Moreover, sustainability issues can be assigned to the department by a precise delineation of responsibility for the respective topic.70 The department functions as a specialized entity, serving as a nexus for sustainability-related information and initiatives and as a designated contact point for corporate sustainability. Additionally, when the topic has a high relevance within the company, a dedicated sustainability department can if circumstances permit, underscore the significance of sustainability within the company and promote its awareness among all employees.69

Nevertheless, it poses challenges to sustainability implementation as the substantial expenses associated with staffing the sustainability department with personnel lead to increased fixed costs. Moreover, the functional structure can impede coordination among departments, an aspect that has been previously identified as a critical challenge in organizational structures for sustainability.69 As an interdisciplinary subject, sustainability necessitates comprehensive implementation across all departments, irrespective of the presence of a dedicated sustainability department. The strong centralization of the topic of sustainability in a separate department hinders the exchange, interaction, participation, and inclusion of employees from a wide variety of departments and levels in the process, which is essential for sustainability. Thus, it impedes the successful implementation of sustainability efforts in the company.19 In addition, studies have demonstrated that the role of sustainability employees within a functional structure was often not sufficiently apparent, thereby limiting its capacity to influence the company’s sustainability strategy.16 Additionally, the presence of departmental egoisms can result in each department striving to optimize itself, even at the expense of other departments or the corporate sustainability efforts.31 This can result in diminishing the relevance of the sustainability topic, consequently negatively impacting its implementation.

It can, therefore, be seen that some prerequisites for the establishment of a distinct sustainability department must be met. Firstly, the competencies of the sustainability department, as well as the company´s goals and willingness to implement sustainability holistically, must be clearly defined. With the comprehensive nature of sustainability, the topic exerts a profound influence on the actions of the entire company. Consequently, all departments must provide support for corresponding sustainability measures in order to be successful.69 As a result, this organizational structure, in particular, is suitable for medium-sized organizations with a limited diversification of their activities to effectively incorporate sustainability.70

3.3.2 Line-and-staff Organization

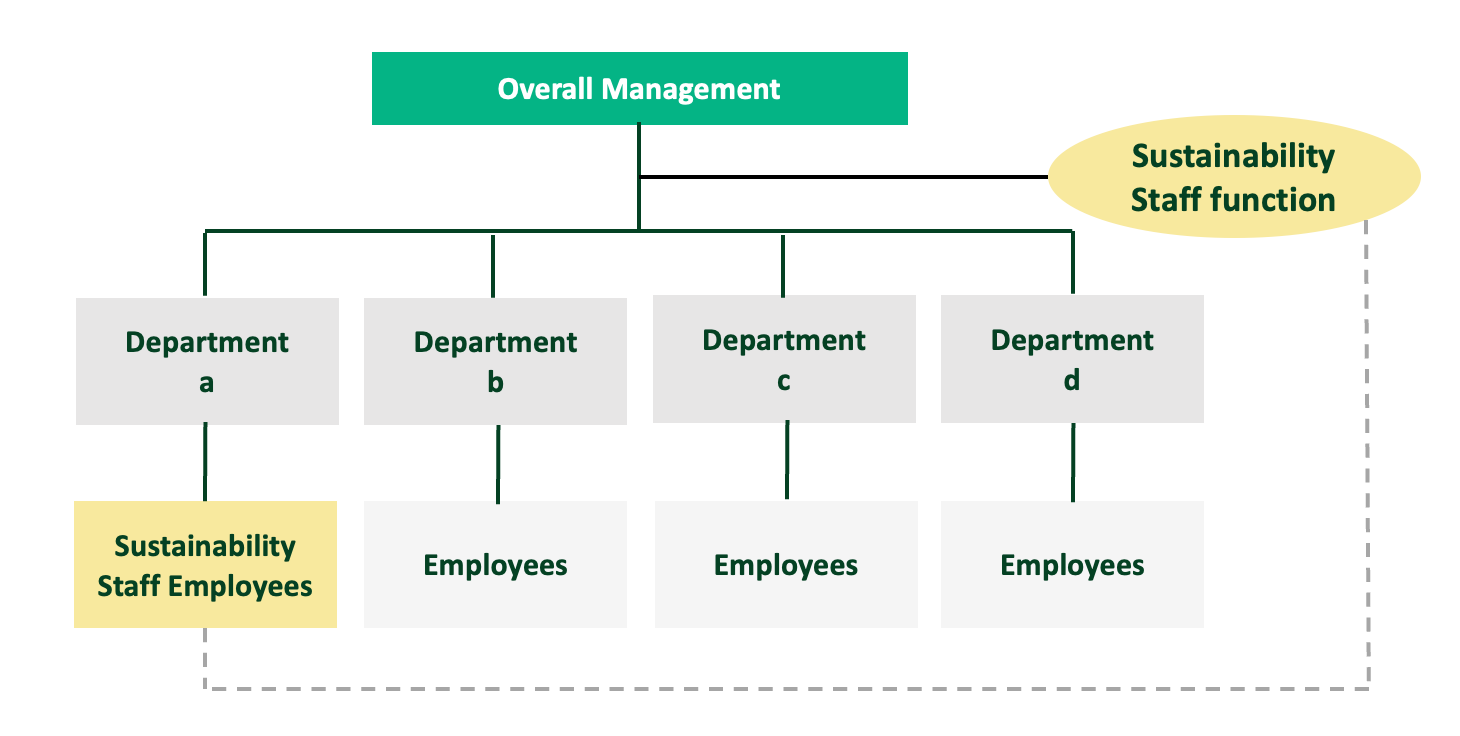

Integrating sustainability into a line-and-staff organization can take on several forms. Sustainability can be integrated solely as a staff function, or linked to one or more departments69 as depicted in Figure 9.

Sustainability as a staff function is characterized by the fact that it reports to management and has an advisory function for departments or management. Moreover, staff functions do not have the authority to issue directives.31 That´s why they are often used at the beginning of a corporate sustainability process when the possibilities and developments are still unclear. The goal of establishing sustainability as a staff function is to build up initial sustainability competencies and to bundle existing activities.69

This organizational structure is advantageous for sustainability due to its capacity for simple integration and manageable costs. It can also provide an initial overview of the topic and create further planning for deeper implementation of sustainability. For this reason, a sustainability staff unit is particularly suitable in the initial phase, during which it is not yet possible for the staff unit to intervene in operational management without the authority to issue directives. This arrangement can be beneficial in the early stages of implementing sustainability strategies, as it allows for the development of a comprehensive and long-term approach. However, it is important to note that this structure can also present challenges in the long term due to the limited decision-making authority and the constraints on the scope of activities.69

An additional disadvantage of this organizational structure is the lack of expertise to make department-specific sustainability decisions. As previously stated, the exchange and transfer of information, as well as the interaction of different perspectives, is an important component of successful sustainability implementation.19 Furthermore, conflicts can also arise due to unclear authority or a slow decision-making process due to the lack of authority of the sustainability staff. The decision-making process is inefficient due to the separation of the preparation, decision, and implementation of sustainability initiatives.32 As sustainability grows in importance within the company, the staff may become overworked, potentially leading to a shortage of resources to address sustainability issues effectively.69 In this case, the sustainability staff function is often linked to a department.

3.3.3 Line-and-staff Organization with Linkage to Department

A departmental connection of the sustainability staff often results from the fact that, in the course of implementing sustainability measures, it is recognized that a certain department should focus more strongly on the topic, or the staff unit is overworked. If it’s shown to be relevant in several departments, it can also result in multiple departmental links, i.e., sustainability competencies can be developed in parallel in different departments. The prerequisite for such an organizational structure is that the connection to the staff function is maintained. This ensures an overarching perspective, facilitating the consolidation and oversight of sustainability initiatives.69

This organizational form presents several advantages, including the simple integration of sustainability into an existing organizational structure, the clarity of costs, and the more efficient and holistic development of sustainability expertise within the company. In addition, the link to a specific department means that specific sustainability knowledge can be built up, processed, and applied directly.69 In contrast, sustainability employees are accountable to both the head of the staff function and the head of the department, resulting in a more challenging working environment. The double subordination requires enhanced coordination between the managers and increased competence of the employees in dealing with it.31,33

3.3.4 Divisional Organization

The emergence of divisional structures for sustainability within organizations is often driven by the expansion of corporate interests into new areas such as sustainability. A notable observation is the formation of teams within departments before the establishment of divisional structures, intending to address sustainability challenges on an operational level.16 However, restructuring the corporate structure into divisions, each with a defined responsibility for a distinct business area, introduces trade-offs for sustainability integration.

A divisional structure, as depicted in Figure 10 has been shown to enhance coordination, as sustainability strategies can be implemented with greater efficacy through the centralized management of a sustainability division.16 Additionally, such a structure is characterized by greater flexibility, partly due to shorter communication channels31, resulting in the ability to respond more rapidly to changes in the market or to regulatory measures. This is a significant advantage for a dynamic field such as sustainability. Furthermore, a divisional structure promotes decentralized decision-making,70 facilitating the integration and transfer of a wide range of perspectives, knowledge, and expertise from within the company, which has been shown to be an essential characteristic for successful sustainability implementation (see Chapter 3.1).19

Conversely, the establishment of divisions can impede the consideration of specific sustainability requirements of each of the companies’ departments, which can hinder the efficacy of the corporate sustainability implementation process. Moreover, the effectiveness of a structured approach to sustainability is contingent upon the provision of financial and human resources. The provision, in turn, is significantly influenced by the support and prioritization of sustainability measures by the upper management as well as the cooperation between divisions.16

3.3.5 Decentralized Sustainability Jobs

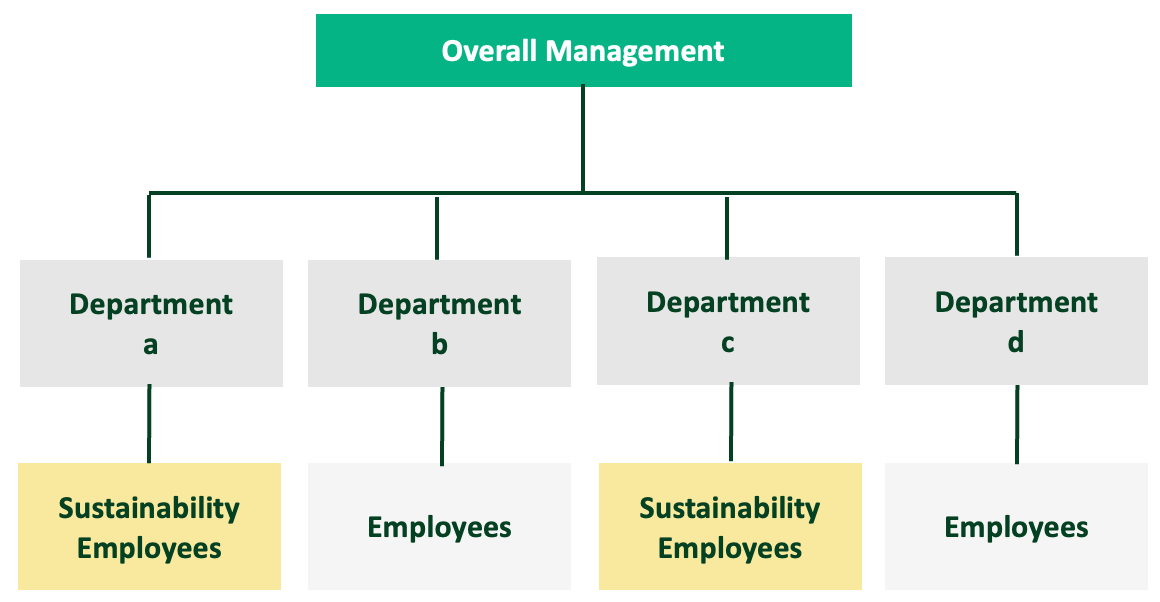

Another organizational model to structure corporate sustainability identified in the literature is to establish decentralized jobs for sustainability employees in one or more departments.

This structure is considered a short-term approach to sustainability as it is relatively simple to integrate compared to other organizational structures and is less cost-intensive.69 Decentralized sustainability employees contribute to the horizontal complexity of the company by allocating sustainability-related tasks within different departments. However, for a company to benefit from horizontal complexity, suitable communication channels are required for the exchange between the sustainability employees to facilitate the exchange of knowledge and expertise for the development of innovative and comprehensive sustainability solutions (see Chapter 3.1).12

Consequently, a decentralized integration of sustainability employees, as depicted in Figure 11 would be considered less suitable for a long-term integration of sustainability as it is less appropriate for achieving the overall goal of sustainability across the company. This is due to a lack of interdisciplinarity and opportunities for exchange and transfer, resulting in missing continuous consultations for company-wide sustainability coordination. Moreover, sustainability knowledge is built up selectively, and the risk of divisional egoism hinders the implementation of sustainability. As a result, this organizational structure is less advantageous for the holistic promotion and implementation of sustainability within the company.69

3.3.6 Matrix Organization

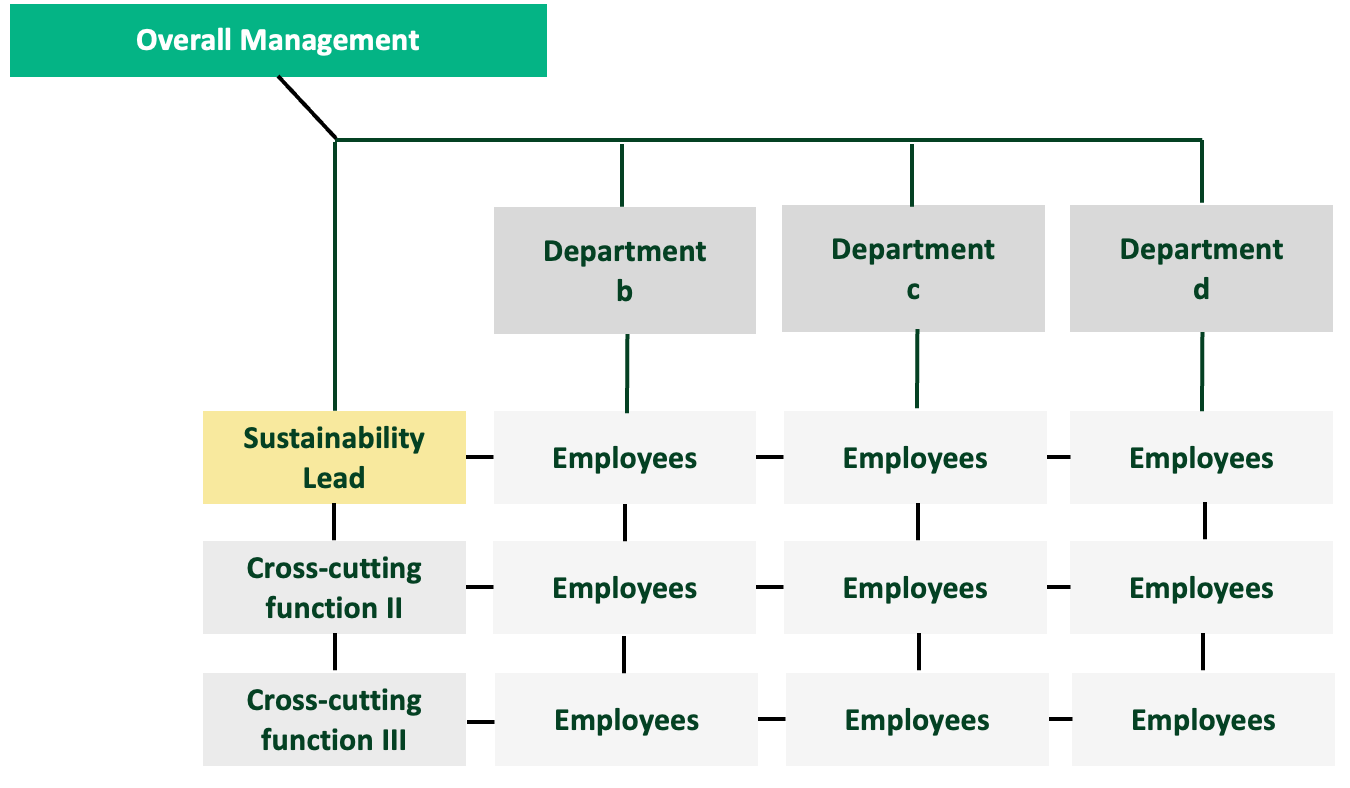

One of the most effective and efficient ways of integrating sustainability into an organization, as stated in the literature, is the cross-cutting/matrix function (see Chapter 2.3.6 Matrix structure).69 As illustrated in Figure 12, sustainability is among several cross-cutting functions incorporated into all areas. This integration results in the following advantages for implementing sustainability.

Firstly, it enables the alignment of sustainability requirements across all departments through an interdisciplinary approach that fosters a holistic interaction with sustainability within the organization. Secondly, it promotes the development of sustainability expertise across various departments, facilitating the exchange and integration of interdisciplinary knowledge.32 This results in an organizational-wide approach to strengthen sustainability efforts rather than initiatives of individual departments. In this case, it can be demonstrated that all departments are able and forced to contribute to its sustainable development, while the coordination and consolidation of sustainability measures are still centralized with the cross-cutting function. This ensures a comprehensive overview of the company´s sustainability measures, challenges, and approaches. Furthermore, it is also possible to respond more quickly to changing requirements, as one function retains an overview.69

However, if a company opts to adopt this organizational structure with the aim of promoting sustainability, it must acknowledge the potential for conflicts that may emerge as a consequence of employees being subject to two areas of responsibility.33 This configuration necessitates a high degree of competence. On the one hand, this demands a greater degree of competence from employees due to the multiple subordination. On the other hand, it requires a substantial level of management competence to orchestrate all cross-sections.33 It is also possible that sustainability-related topics are not sufficiently prioritized in individual departments and that these topics cannot be dealt with to the extent required for efficient and effective holistic implementation. A prioritization or interweaving of departmental and sustainability-specific topics must, therefore, be found.69

3.3.7 Network Organization

As mentioned in Chapter 2.3.7, network structures can be categorized into internal and external networks.33 The latter type has gained greater recognition in several contexts, including the field of sustainability.32 In literature, the Interactions and Networks Approach (INA) has emerged that examines the dynamics of networks and their impact on learning and transformation processes within organizations in the context of sustainability. Within this approach, the environment is not regarded as a separate entity but rather as a comprehensive concept that is built on dialogue and cooperation. This approach has been further reinforced by a growing body of literature highlighting the increasing importance of inter-organizational relationships, alliances, and partnerships for corporate sustainability.71 The primary focus of this discussion is the notion that achieving sustainability necessitates not only the actions of individual organizations but also systemic change within companies and the market as a whole.72 This concept can be facilitated by network structures, which will be discussed briefly. The inherent complexity of the sustainability challenge often poses a significant obstacle for companies. The exchange of knowledge, the integration of stakeholder perspectives, and cooperation with external actors such as communities and NGOs can facilitate the development of the necessary skills and resources for sustainable solutions and innovations. This, in turn, supports the overall economic sustainability transformation as well as the internal sustainable development of the company.71 This is due to the fact that (sustainability) knowledge derived from inter-organizational networks exerts an influence on the knowledge within organizations, which can be disseminated in intra-organizational networks.73

However, extant literature demonstrates that internal network structures for sustainability are regarded more as an accompanying structural element than as an independent structure. The significance of internal networks for the successful implementation of sustainability is reflected in the development of mechanisms to integrate activities from different organizational units and to accelerate the access and transfer of information regarding sustainability. Therefore, internal networks are regarded as a supportive instrument rather than a structure itself defining authorities, tasks, and official communication channels.74

3.3.8 Team Organization

In recent years, the characteristics of team organizations, namely, among others, the ability to adapt quickly to changing environmental conditions, have emerged as a structure for sustainability.32 Additionally, the nature of sustainability aligns with the characteristics that make the use of team organizations advantageous. These include the complexity and significance of the task/project for the company, the impact on and involvement of several areas of the company, as well as the need for interdisciplinary expertise.32 This enables the positive effects of a team organization to be used for corporate sustainability. The integration of a team comprising members from different departments fosters horizontal complexity, facilitating the accumulation of information, knowledge, and creativity from multiple disciplines. This, in turn, enables the development of innovative and comprehensive sustainability solutions.12 Moreover, the team members can serve as channels for knowledge transfer between departments, thereby enhancing the exchange of ideas and expertise. Consequently, communication channels can be shortened, and the benefits of synergy can be realized. This also has coordination advantages that are beneficial for a complex topic such as sustainability.32 Furthermore, team members can function as previously outlined sustainability change agents within their respective departments and the team itself. This enables them to facilitate strategic and normative organizational change towards sustainability.19

However, team dynamics present challenges as well. The diverse composition of the group can lead to difficulties in defining the team’s competencies and areas of responsibility, as well as a prolonged decision-making process due to conflicts and discussions within the team. Additionally, individual team members’ interests in sustainability can become dominant or differ, and team members could be overworked due to the additional responsibility and tasks on the team.32

3.3.9 Project Organization

With regard to sustainability, the advantages and disadvantages of project organizations outlined in Chapter 2.3.8demonstrate that such a structure is barely adequate for a complex and long-term subject such as sustainability. Sustainability requires interdisciplinarity, a holistic and long-term approach, and transfer,75 which is hindered by the challenges posed by a project structure, namely limited resources and the existence of the structure resulting in instability and communicational challenges.32 That´s why this organizational type for sustainability is absent in the literature.

In conclusion, it has been shown that a multitude of organizational structures for sustainability exists, each with its own set of trade-offs. Given the unique characteristics of each company, a ‘one fits all’ solution is not applicable, thus, a customized approach is necessary for identifying the most suitable structure.36 Additionally, research has demonstrated that the temporal dimension, encompassing the age and developmental stage of a company, is a contributing factor in the selection of an organizational structure for sustainability as well.16,18,69 The subsequent chapter will provide a comprehensive overview of the extant literature addressing maturity models for organizational structures for sustainability.

3.4 Evolution of Organizational Structures for Sustainability

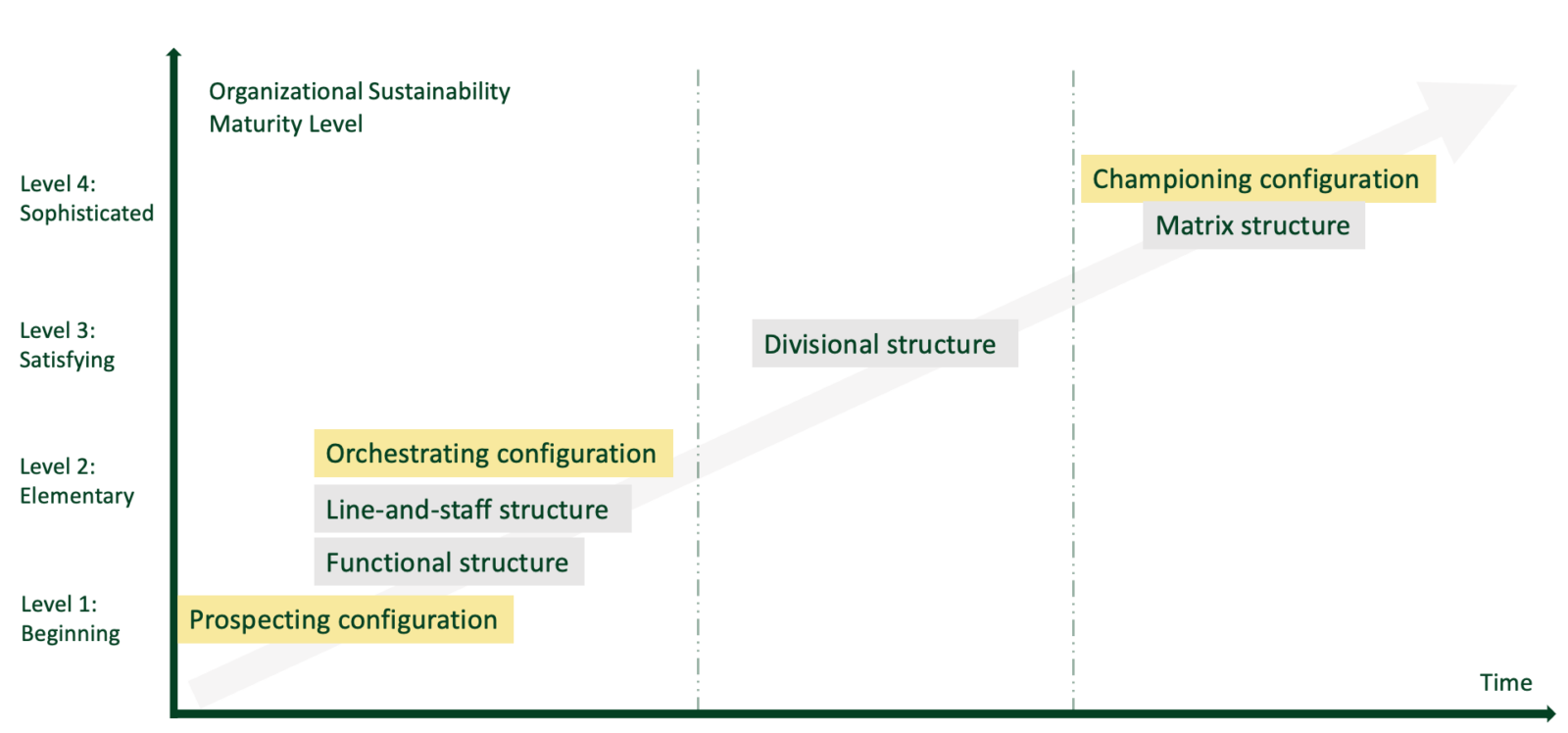

The development over time and the implementation of organizational structures for sustainability demonstrate how companies adapt to changing requirements and priorities regarding sustainability. Empirical research identified an interrelationship between the maturity of corporate sustainability and the adoption of different structures for sustainability. An organization progresses through several maturity levels in its sustainability process.69 In this process the consideration of maturity levels of corporate sustainability when selecting organizational structures for sustainability can have a positive impact.76

Maturity levels describe the stages of development of an organization with regard to certain processes or activities, including corporate sustainability.77 These levels provide a framework for understanding the development from an initial phase to advanced stages and thus enable an assessment of this progress, as well as the definition of clear goals for the sustainable development of organizations. In the extant literature, various approaches have been developed to describe the maturity levels of companies.78 Regarding corporate sustainability, the model by Baumgartner and Ebner (2010) is the most comprehensive one and includes the following four maturity levels for corporate sustainability.76

Maturity Level 1 – Beginning: At this level, a basic consideration of sustainability aspects is initiated, which is limited to compliance with legal requirements.

Maturity Level 2 – Elementary: Companies integrate initial approaches to reducing their business activities’ impacts that extend beyond compliance with regulations.

Maturity Level 3 – Satisfying: Satisfactory consideration of sustainability aspects is achieved at this level, often above the industry average.

Maturity Level 4 – Sophisticated/Outstanding: This is the highest maturity level, which includes an exceptional commitment to sustainability. The company acts proactively and innovatively in all relevant areas and takes on leading roles in the area of sustainability.

In the early stages of development, marked by Maturity levels 1 (Beginning) and 2 (Elementary), sustainability is primarily driven by external factors such as regulatory requirements or reputational risks, rather than being intrinsically motivated.18 The study by Sandhu and Kulik (2019) identified three different configurations (‘Prospecting’, ‘Orchestrating’, and ‘Championing’) that are characterized by different degrees of formalization and centralization and their impact on sustainability in companies. The configurations also represent a development of an increasing prioritization of sustainability in the company. The prospecting and orchestrating configurations can be categorized into the first two maturity levels. The prospecting configuration is characterized by a low degree of formalization and centralization, which often results in role ambiguity regarding the employee responsible for sustainability issues. Moreover, due to the low relevance of sustainability engagement, the role of sustainability employees has limited discretion and access to resources for sustainability initiatives. That’s why this configuration is frequently observed in companies that are in the initial stages of implementing sustainability measures.18

The orchestrating configuration emerges as a further development of the prospecting configuration and is marked by a high degree of formalization and centralization. In this configuration, the role of a sustainability officer is highly centralized but not embedded in other functional areas, which further complicates the prioritization of sustainability throughout the company. Although sustainability initiatives are supported and the necessary resources are made available, this is only within the framework of the formalized agenda. Independent sustainability initiatives that do not align with this strict agenda have encountered challenges in achieving bottom-up adoption. Consequently, innovative approaches to corporate sustainability commitment have met with limited success, leading to a decline in the enthusiasm and dedication to sustainability issues among the initiators.18

A frequently implemented structure in this phase is the line-and-staff structure, in which a centralized staff function is responsible for the coordination and monitoring of sustainability measures.69 In addition to the line-and-staff structure, other studies have identified functional structures to be used in this stage of sustainability development. These are also characterized by the presence of centralized sustainability employees, whose influence is limited due to their localization in the lower parts of the structure. Consequently, these employees are particularly noticeable in the context of initial sustainability efforts.16

An increasing focus on sustainability, coupled with the development towards Maturity level 3 (satisfying), results in the introduction of divisional structures. This development is often driven by the objective of enhancing the integration of sustainability into specific business areas or departments. However, the efficacy of these structures is contingent upon the allocation of adequate resources and the dedication of divisional management.16 This level is also characterized by further development of the staff function through departmental integration or the establishment of dedicated sustainability jobs within departments.69

At the advanced stage (Maturity level 4 sophisticated) of corporate sustainability, companies increasingly adopt flexible, decentralized structures that enable cooperation between departments. The championing configuration emerging from the study by Sandhu and Kulik (2019) can be classified at this level as well. In accordance with the previously presented literature findings, this configuration, found to be the most efficient, is characterized by a decentralized structure that empowers employees to develop and implement social and environmental initiatives bottom-up. An important aspect is the involvement of a wide range of stakeholders and various functional areas within the company for a comprehensive and inclusive approach to sustainability efforts. Additionally, the study notes that a low level of formalization allows for greater flexibility and the development of innovative initiatives and solutions, highlighting the value of adaptability in promoting sustainability. This configuration was found present in organizations that have a high maturity level regarding sustainability and the objective to implement it long-term and on a normative level.18 At this maturity level, the increasing integration of sustainability is often met with the formation of sustainability as a cross-cutting function. This allows for the promotion of specific requirements of individual departments as well as a holistic sustainability orientation and implementation.69 Hybrid structures are also used, in which several structures are combined to integrate, among others, elements of matrix organizations in order to implement comprehensive sustainability efforts in an interdisciplinary manner.16

Finally, it should be noted that these are models derived from the research literature and that the practical application of organizational structures for sustainability may differ. For instance, developmental phases as shown in Figure 13, and associated structures may be skipped or combined.69 Consequently, the generalization of the model and structures presented remains a challenge and a limitation of research in this domain, which will be addressed in the subsequent chapter.

3.5 Outlook for Future Research

The increasingly dynamic nature of the business environment requires companies to adapt their structures to remain sustainable and competitive. Consequently, research on organizational structures for sustainability must align with this dynamism and change to provide meaningful assistance to companies and to genuinely promote sustainable outcomes.19As a result, several challenges of current and future research can be identified.

The most significant challenge confronting contemporary research is the lack of a comprehensive examination of organizational structures for sustainability. While research acknowledges the relationship between organizational structures and corporate sustainability, there is a need for more in-depth knowledge regarding the nature of this relationship. To date, there have been merely transfers of classic organizational forms to the topic of sustainability, with no explicit structures developed in this area.12

An additional primary challenge and weakness in research on organizational structures for sustainability is their limited generalizability. The efficacy of structures for sustainability is contingent on specific factors, including company size, geographical location, and industry, resulting in a lack of universal applicability.11 Furthermore, as previously mentioned, structures should be dynamic and evolve in line with the business environment. In a dynamic field such as sustainability, this necessitates continuous adaptation and change, complicating the research of long-term effectiveness.19

Another weakness that has been identified is the adoption of structures that often arise from organizational isomorphism, which means that under external demand organizations and their structures are increasingly converging. These structures can be dysfunctional if organization-specific factors are not adequately considered. Therefore, the literature must take a differentiated view of the impact of organizational structures on sustainability in a wide range of organizations.79

A further challenge is posed by the interconnectedness of structure with other approaches, such as strategy and processes. As outlined in Chapter 2.4, the structure is a part of organizational design, which is reflected in the theory of Organizational Design34 and Galbraith’s Star Model.35 An isolated consideration of organizational structure is, therefore, insufficient to address the integration of sustainability in an organization. A comprehensive understanding of organizational structures, the interactions, and tensions between them and with other concepts is imperative for effective implementation and design. The current literature has shown that so far, rather one-dimensional approaches to the interaction between structure and sustainability have been pursued.12

Moreover, a discrepancy exists between research and practice. The ideal typification of organizational forms in research is rarely observed in business reality. In practice, organizational forms seldom appear in a pure form but rather in fluid transitions, mixtures, or skipping of individual organizational structures. This heterogeneity in practice presents a challenge in developing universally valid statements and requires more differentiated analyses.32

The identified weaknesses suggest the following avenues for future research on organizational structures for sustainability:

- Combination of organizational variables: Firstly, future research should prioritize the examination of combinations of organizational variables over the analysis of isolated structural dimensions for sustainability. A more differentiated approach could facilitate the identification of specific or new configurations that could then be tested to evaluate their relative effectiveness under various internal and external circumstances in comparison to isolated pure organizational structures.12