Author: Malin Maurer, January 10, 2024

1 Understanding of Corporate Sustainability

The understanding and perception of the Corporate Sustainability (CS) concept from both an academic and a practical point of view is the subject of this chapter. The existing differences and characteristics of CS will be discussed, and related concepts will be described and distinguished.

1.1 Definition and Characteristics

The understanding of CS differs depending on the academic or practice-orientated perspective. Thus, this chapter seeks to contribute to a better understanding of the concept by analysing and explaining the definitions and characteristics within the different perspectives. It is also important to differentiate CS from other related concepts.

1.1.1 Practitioner perspective

Since the 1990s, companies have become increasingly aware of their impact on society and the environment. They are expected to essentially contribute to sustainable development, providing or developing solutions to global problems such as climate change. 10 Meuer, J., Koelbel, J. & Hoffmann, V. H. On the Nature of Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 33, 319–341 (2020). CS is considered a company’s ambition to contribute to sustainability in the business context, translating sustainability and sustainable development into a corporate context, considering not only economic but also environmental, and social aspects in assessing a corporation’s performance.1 Moon, J., Murphy, L. & Gond, J.-P. Historical Perspectives on Corporate Sustainability. in Corporate Sustainability: Managing Responsible Business in a Globalised World Vol. 2 (eds Rasche, A., Morsing, M., Moon, J., & Kourula, A.) Ch. 2, 29-54 (2023).2 Schaltegger, S. & Burritt, R. Corporate Sustainability. The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 2005/2006., 336 (2005). 21Ashrafi, M., Magnan, G. M., Adams, M. & Walker, T. R. Understanding the Conceptual Evolutionary Path and Theoretical Underpinnings of Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Sustainability. Sustainability 12, 760 (2020). Due to this connection, both terms, CS and sustainable development, are often used interchangeably.22Schaltegger, S. Von CSR zu Corporate Sustainability. in Corporate Social Responsibility in kommunalen Unternehmen – Wirtschaftliche Betätigung zwischen öffentlichem Auftrag und gesellschaftlicher Verantwortung (eds Sandberg, B. & Lederer, K.) 187-199 (VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2011). See Chapter 3.3.1.1 for more information on the background of sustainable development.

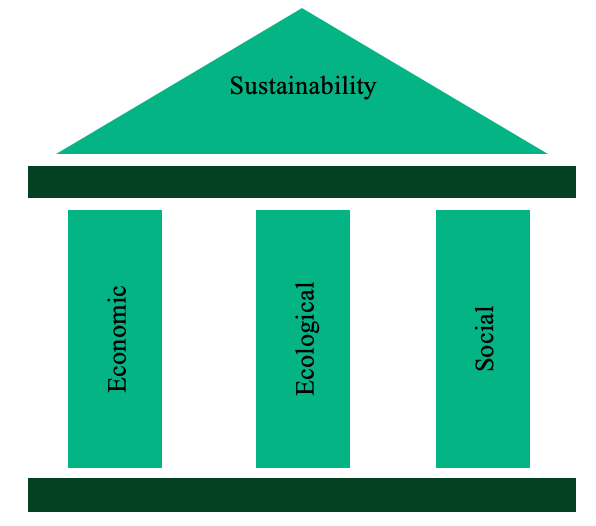

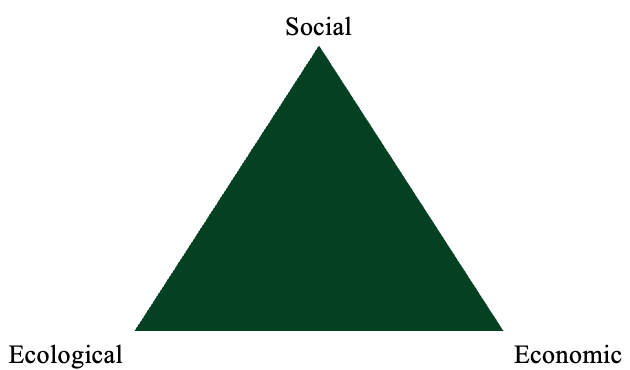

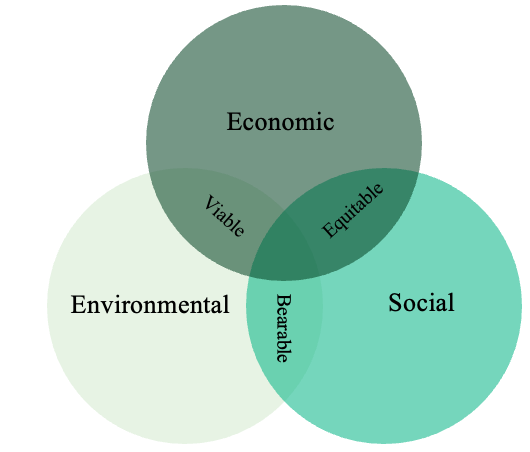

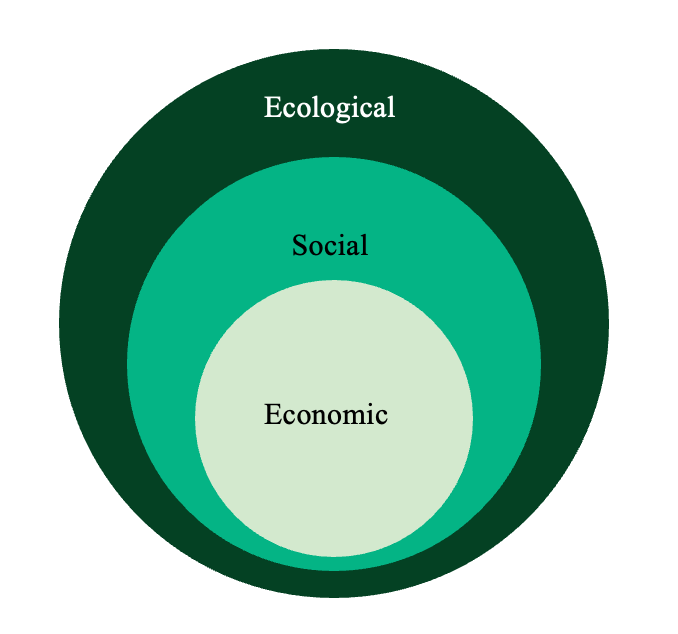

A central assumption of CS is recognising that pursuing economic objectives alone is insufficient or obstructive to achieving sustainability. Although focusing on economic goals can foster short-term gains, it does not support long-term resilience and success. Therefore, all three dimensions – environmental, social and economic – must be addressed simultaneously.23Dyllick, T. & Hockerts, K. Beyond the Business Case for Corporate Sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment 11, 130–141 (2002).24Gladwin, T. N., Kennelly, J. J. & Krause, T.-S. Shifting Paradigms for Sustainable Development: Implications for Management Theory and Research. Academy of Management Review 20, 874-907 (1995). This integrated approach of recognising all dimensions is grounded in John Elkington’s (1998) Triple Bottom Line (TBL) framework, which seeks to emphasize the need to balance economic prosperity, ecological integrity and social justice.2 Schaltegger, S. & Burritt, R. Corporate Sustainability. The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 2005/2006., 336 (2005).25Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks. (Capstone Publishing, 1997).26Bansal, P. Evolving sustainably: a longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strategic Management Journal 26, 197-218 (2005). Sustainable corporate development can only be achieved if all three dimensions are considered.19Schaltegger, S. Die Beziehung zwischen CSR und Corporate Sustainability. in Corporate Social Responsibility (eds Schneider, A. & Schmidpeter, R.) 199-209 (Springer Gabler, 2015).22Schaltegger, S. Von CSR zu Corporate Sustainability. in Corporate Social Responsibility in kommunalen Unternehmen – Wirtschaftliche Betätigung zwischen öffentlichem Auftrag und gesellschaftlicher Verantwortung (eds Sandberg, B. & Lederer, K.) 187-199 (VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2011).26Bansal, P. Evolving sustainably: a longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strategic Management Journal 26, 197-218 (2005).27Ashrafi, M., Adams, M., Walker, T. R. & Magnan, G. How corporate social responsibility can be integrated into corporate sustainability: a theoretical review of their relationships. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 25, 672-682 (2018). The following section briefly elaborates on the different dimensions. Further information on the TBL framework is provided in Chapter 3.3.1.2.

Ecological dimension

The ecological dimension addresses a company’s impact on its natural environment, focusing on the impacts of corporate activities on the (natural) environment, e.g., resource use, emissions (into air, water, ground), waste and the impact on ecosystems and biodiversity.28Labbé, M. & Stein, H.-J. Nachhaltigkeitsberichte als Instrument der Unternehmenskommunikation. DER BETRIEB, 2661-2667 (2007).29Baumgartner, R. J. & Ebner, D. Corporate Sustainability Strategies: Sustainability Profi les and Maturity Levels. Sustainable Development 18, 76-89 (2010). The ecological dimension can be measured through impact analysis and evaluation. The main target should be to reduce the negative impact of business activities (e.g., production processes, products, investments) on the environment, preserve ecosystems, and use resources efficiently and sparingly.2 Schaltegger, S. & Burritt, R. Corporate Sustainability. The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 2005/2006., 336 (2005).28Labbé, M. & Stein, H.-J. Nachhaltigkeitsberichte als Instrument der Unternehmenskommunikation. DER BETRIEB, 2661-2667 (2007).29Baumgartner, R. J. & Ebner, D. Corporate Sustainability Strategies: Sustainability Profi les and Maturity Levels. Sustainable Development 18, 76-89 (2010).30Aragón-Correa, J. A. Strategic proactivity and firm approach to the natural environment. Academy of Management Journal 41, 556-567 (1998).Thus, environmentally sustainable companies do not use more resources than they need to produce and deliver their products and services. Furthermore, they pay attention to the emissions they produce and try to reduce their impact on the environment.23Dyllick, T. & Hockerts, K. Beyond the Business Case for Corporate Sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment 11, 130–141 (2002).

Economic dimension

The economic dimension emphasizes the importance of financial sustainability for companies to be profitable over the long term.29Baumgartner, R. J. & Ebner, D. Corporate Sustainability Strategies: Sustainability Profi les and Maturity Levels. Sustainable Development 18, 76-89 (2010). In classical economic theory, a company’s primary goal is to achieve continuous growth in the value and profitability of the company.2 Schaltegger, S. & Burritt, R. Corporate Sustainability. The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 2005/2006., 336 (2005).31Sawczyn, A. Unternehmerische Nachhaltigkeit und wertorientierte Unternehmensführung: empirische Untersuchung der Unternehmen im HDAX. Vol. 4 (Dr. Kovač, 2011). Companies that manage this dimension efficiently will likely succeed, leading to financially rewarding results.29Baumgartner, R. J. & Ebner, D. Corporate Sustainability Strategies: Sustainability Profi les and Maturity Levels. Sustainable Development 18, 76-89 (2010). While corporate profitability remains a priority in this dimension, a CS perspective also considers social and environmental factors.2 Schaltegger, S. & Burritt, R. Corporate Sustainability. The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 2005/2006., 336 (2005).31Sawczyn, A. Unternehmerische Nachhaltigkeit und wertorientierte Unternehmensführung: empirische Untersuchung der Unternehmen im HDAX. Vol. 4 (Dr. Kovač, 2011). This includes aspects like innovation and technology, knowledge management or processes.29Baumgartner, R. J. & Ebner, D. Corporate Sustainability Strategies: Sustainability Profi les and Maturity Levels. Sustainable Development 18, 76-89 (2010). According to Dyllick and Hockerts (2002), economically sustainable companies can always ensure financial solvency while providing shareholders a return.23Dyllick, T. & Hockerts, K. Beyond the Business Case for Corporate Sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment 11, 130–141 (2002).

Social dimension

The social dimension of CS is concerned with the social impact of a company’s activities on its employees, stakeholders and the community in which it is embedded.29Baumgartner, R. J. & Ebner, D. Corporate Sustainability Strategies: Sustainability Profi les and Maturity Levels. Sustainable Development 18, 76-89 (2010). It encompasses the reduction of negative impacts as well as the consideration and response to corresponding demands from society. This is also closely related to the issue of corporate legitimacy, which is not discussed further here. Other relevant aspects of the social dimension include addressing social grievances and equity issues, such as interregional or intertemporal equity.2 Schaltegger, S. & Burritt, R. Corporate Sustainability. The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 2005/2006., 336 (2005). Examples include consideration of employee interests, occupational health and safety, training, and the company’s impact on society/stakeholders outside the company.2 Schaltegger, S. & Burritt, R. Corporate Sustainability. The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 2005/2006., 336 (2005).28Labbé, M. & Stein, H.-J. Nachhaltigkeitsberichte als Instrument der Unternehmenskommunikation. DER BETRIEB, 2661-2667 (2007).31Sawczyn, A. Unternehmerische Nachhaltigkeit und wertorientierte Unternehmensführung: empirische Untersuchung der Unternehmen im HDAX. Vol. 4 (Dr. Kovač, 2011). Next to reducing negative impacts, socially sustainable companies add value to the community they are embedded in.23Dyllick, T. & Hockerts, K. Beyond the Business Case for Corporate Sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment 11, 130–141 (2002).

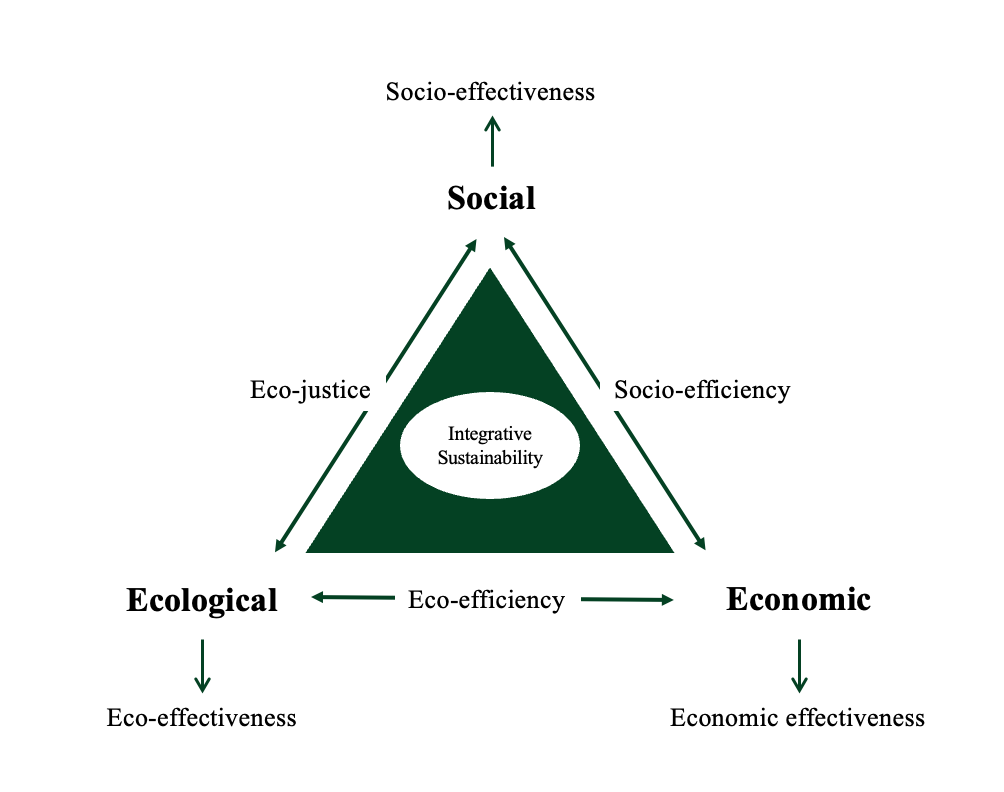

CS focuses on how companies can (strategically) pursue the three dimensions equally. However, doing so often requires navigating trade-offs. Figure 1 illustrates the sustainability triangle (see Chapter 3.3.1.3) extended by the main challenges arising from the simultaneous considerations and the trade-offs. As a classical entrepreneurial task, economic effectiveness is usually considered a company’s primary business goal to achieve the best economic outcome.2 Schaltegger, S. & Burritt, R. Corporate Sustainability. The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 2005/2006., 336 (2005).31Sawczyn, A. Unternehmerische Nachhaltigkeit und wertorientierte Unternehmensführung: empirische Untersuchung der Unternehmen im HDAX. Vol. 4 (Dr. Kovač, 2011). Nevertheless, in the context of CS, economic effectiveness is not the only challenge companies must tackle. If companies want to act sustainably, addressing one dimension without impacting the other two is rarely possible. The challenges companies face can be categorized into effectiveness and efficiency-related issues. According to Schaltegger et al. (2016), effectiveness strives to improve a single dimension, such as eco-effectiveness or socio-effectiveness, while efficiency describes the relationship between different dimensions, such as eco-efficiency, socio-efficiency and eco-justice.32Schaltegger, S., Hansen, E. G. & Spitzeck, H. Corporate Sustainability Management. 85-97 (Springer Netherlands, 2016). Together, they present and systematize the main challenges for companies regarding CS. The ecological challenge seeks to increase eco-effectiveness; the socio challenge aims to increase socio-effectiveness, and the “economic challenge to environment and social management” (p. 191) to increase the socio- and eco-efficiencies.2 Schaltegger, S. & Burritt, R. Corporate Sustainability. The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 2005/2006., 336 (2005). In the following, the criteria are briefly explained:

- Eco-Effectiveness: Measuring the degree of absolute environmental compatibility, i.e., how well the desired goal of minimizing negative environmental impact has been achieved. According to Schaltegger and Burritt (2005), this indicates how successfully a company meets the ecological challenge.2 Schaltegger, S. & Burritt, R. Corporate Sustainability. The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 2005/2006., 336 (2005).18Schaltegger, S., Herzig, C., Kleiber, O., Klinke, T. & Müller, J. D. Nachhaltigkeitsmanagement in Unternehmen : Von der Idee zur Praxis: Managementansätze zur Umsetzung von Corporate Social Responsibility und Corporate Sustainability. (2007).

- Eco-Efficiency: Economic-ecological efficiency is “the ratio of an economic (monetary) to a physical (ecological) measure” (p. 192).2 Schaltegger, S. & Burritt, R. Corporate Sustainability. The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 2005/2006., 336 (2005). In this approach, the economical parameter is included as the value added, the ecological one as the (harmful) environmental impact, whereby the environmental impact is regarded as the sum of all direct and indirect environmental impacts caused by a product or service 2 Schaltegger, S. & Burritt, R. Corporate Sustainability. The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 2005/2006., 336 (2005). Examples, according to Schaltegger and Burritt (2005) are: value added (in $ or Euro)/per tonne of emitted CO2 or contribution margin of a product (in $ or Euro)/contribution to greenhouse effect (in CO2 equivalents).2 Schaltegger, S. & Burritt, R. Corporate Sustainability. The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 2005/2006., 336 (2005).

- Socio-Effectiveness: The criterion provides information on how much negative societal effects have been reduced. Beyond this, the criterion can also assess how much the positive impact has been increased.2 Schaltegger, S. & Burritt, R. Corporate Sustainability. The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 2005/2006., 336 (2005).18Schaltegger, S., Herzig, C., Kleiber, O., Klinke, T. & Müller, J. D. Nachhaltigkeitsmanagement in Unternehmen : Von der Idee zur Praxis: Managementansätze zur Umsetzung von Corporate Social Responsibility und Corporate Sustainability. (2007).

- Socio-efficiency: Indicates the relation of economic value added to the company’s (negative) social impact concerning its products, processes, and activities.2 Schaltegger, S. & Burritt, R. Corporate Sustainability. The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 2005/2006., 336 (2005). Examples include the ratio of value-added [EUR]/personal accidents [number] or value-added [EUR]/sick leave [days].18Schaltegger, S., Herzig, C., Kleiber, O., Klinke, T. & Müller, J. D. Nachhaltigkeitsmanagement in Unternehmen : Von der Idee zur Praxis: Managementansätze zur Umsetzung von Corporate Social Responsibility und Corporate Sustainability. (2007).

- Eco-justice: Provides information on “the ratio between environmental and social objectives or indicators, e.g., environmental impacts relative to poverty” (p. 91).32Schaltegger, S., Hansen, E. G. & Spitzeck, H. Corporate Sustainability Management. 85-97 (Springer Netherlands, 2016).

- Integrative Sustainability: The main objective for companies should be to satisfy the three dimensions of sustainability simultaneously.2 Schaltegger, S. & Burritt, R. Corporate Sustainability. The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 2005/2006., 336 (2005). Doing so requires equal consideration and improvement of eco-effectiveness, socio-effectiveness, eco-efficiency and socio-efficiency.2 Schaltegger, S. & Burritt, R. Corporate Sustainability. The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 2005/2006., 336 (2005).18Schaltegger, S., Herzig, C., Kleiber, O., Klinke, T. & Müller, J. D. Nachhaltigkeitsmanagement in Unternehmen : Von der Idee zur Praxis: Managementansätze zur Umsetzung von Corporate Social Responsibility und Corporate Sustainability. (2007).

In the corporate context, sustainability is often implemented based on ESG criteria. The criteria refer to environmental (E), social (S), and governance (G) sustainability issues within corporations. They present an instrument and framework to assess, analyse, measure, and evaluate efforts to implement CS.33Schölzel, A. ESG – Definition und Bedeutung für Unternehmen und Investoren, Accessed on 02.01, 2025, <https://www.haufe.de/sustainability/strategie/esg-definition-und-bedeutung-fuer-unternehmen-und-investoren_575772_625088.html> (2024). In doing so, the ESG criteria consist of different indicators, functioning as a basis for further evaluation and assessment and as the foundation for rating agencies to evaluate a company’s sustainability performance.34Tenuta, P. & Cambrea, D. R. ESG Measures and Non-financial Performance Reporting. 27-58 (Springer International Publishing, 2022). Further information on the practical implementation of sustainability into businesses is provided in Chapter 4.

1.1.2 Academic perspective

The following section explores the academic perspective on the CS concept, paying particular attention to the understanding and definitions published in the scientific literature.

In this context, CS emerges as a complex and holistic concept that is difficult to grasp. In the last decade, CS has been studied by scholars from different disciplines, such as economics, politics, law and the natural sciences, which underlines the complexity of the concept.8Montiel, I. & Delgado-Ceballos, J. Defining and Measuring Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 27, 113–139 (2014).35Hahn, T., Figge, F., Aragón-Correa, J. A. & Sharma, S. Advancing research on corporate sustainability: Off to pastures new or back to the roots? Business & Society 56, 155-185 (2017).36Garren, S. J. & Brinkmann, R. Sustainability definitions, historical context, and frameworks. The Palgrave Handbook of Sustainability: Case Studies and Practical Solutions, 1-18 (2018). Despite this, Ashrafi et al. (2020) conclude that in the academic CS debate, there is less disagreement among researchers about the definition of CS due to its roots in the sustainable development debate.21Ashrafi, M., Magnan, G. M., Adams, M. & Walker, T. R. Understanding the Conceptual Evolutionary Path and Theoretical Underpinnings of Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Sustainability. Sustainability 12, 760 (2020). In contrast, other scholars criticise the lack of a unified definition, which they attribute to researchers who prefer to use more specific and less complex terms.8Montiel, I. & Delgado-Ceballos, J. Defining and Measuring Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 27, 113–139 (2014).21Ashrafi, M., Magnan, G. M., Adams, M. & Walker, T. R. Understanding the Conceptual Evolutionary Path and Theoretical Underpinnings of Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Sustainability. Sustainability 12, 760 (2020). Therefore, although CS has been studied extensively and various researchers have contributed to a better understanding of this complex concept, establishing a common definition has not yet been possible. 10 Meuer, J., Koelbel, J. & Hoffmann, V. H. On the Nature of Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 33, 319–341 (2020).17Burbano, V. C., Delmas, M. A. & Cobo, M. J. The Past and Future of Corporate Sustainability Research. Organization & Environment (2023). However, some definitions are more widely used than others. One of the earliest and still most cited definitions was published by Dyllick and Hockerts (2002). It states that CS can be defined as:

“[…] meeting the needs of a firm’s direct and indirect stakeholders (such as shareholders, employees, clients, pressure groups, communities etc.), without compromising its ability to meet the needs of future stakeholders as well” (p. 131).23Dyllick, T. & Hockerts, K. Beyond the Business Case for Corporate Sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment 11, 130–141 (2002).

They thus applied the idea of sustainable development from the Brundtland Report to the business level.23Dyllick, T. & Hockerts, K. Beyond the Business Case for Corporate Sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment 11, 130–141 (2002). To date, numerous further definitions have been proposed, some similar to existing ones, while others take different approaches. The following discussion provides a brief overview of the academic discourse on CS, highlighting the similarities and differences between these definitions.

Table 1 and Table 2 provide an (alphabetical) overview of the most commonly used and referenced definitions in the literature on CS. These definitions are based on the literature reviews by Meuer et al. (2020), Montiel and Delgado-Ceballos (2014), and Linneluecke and Griffiths (2013). These reviews focus on analysing different published definitions and the relevance of the articles based on how often they were quoted.8Montiel, I. & Delgado-Ceballos, J. Defining and Measuring Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 27, 113–139 (2014). 10 Meuer, J., Koelbel, J. & Hoffmann, V. H. On the Nature of Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 33, 319–341 (2020). The definitions listed here are a small selection to illustrate the variety of existing definitions. Building upon the three reviews mentioned above, the publications and definitions listed were compared and supplemented by further definitions or authors mentioned more than once during the literature search.

Table 1: Definitions of Corporate Sustainability

| vAuthor(s) | Definition of CS |

| Ashrafi et al. (2019) | “Corporate sustainability (CS) is most widely used to refer to an organization’s approach to creating value in social, environmental, and economic spheres in a long-term perspective, supporting greater responsibility” (p. 1).37Ashrafi, M., Acciaro, M., Walker, T. R., Magnan, G. M. & Adams, M. Corporate sustainability in Canadian and US maritime ports. Journal of Cleaner Production 220, 386–397 (2019). |

| Ashrafi et al. (2020) | “[C]an be understood as the application of sustainable development at the corporate level, including the short-term and long-term economic, environmental, and social aspects of a corporation’s performance (p. 7).21Ashrafi, M., Magnan, G. M., Adams, M. & Walker, T. R. Understanding the Conceptual Evolutionary Path and Theoretical Underpinnings of Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Sustainability. Sustainability 12, 760 (2020). |

| Dyllick and Hockerts (2002) | “[…] meeting the needs of a firm’s direct and indirect stakeholders (such as shareholders, employees, clients, pressure groups, communities etc), without compromising its ability to meet the needs of future stakeholders as well” (p. 131).23Dyllick, T. & Hockerts, K. Beyond the Business Case for Corporate Sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment 11, 130–141 (2002). |

| Hahn and Figge (2011) | “Companies should pursue environmental, social, and economic goals alike in order to achieve long-term prosperity of the firm (organizational target level) or to contribute to the long-term prosperity of society and humankind (societal target level)” (p. 331).7Hahn, T. & Figge, F. Beyond the Bounded Instrumentality in Current Corporate Sustainability Research: Toward an Inclusive Notion of Profitability. Journal of Business Ethics 104, 325–345 (2011). |

| Hahn et al. (2015) | “[C]orporate sustainability refers to a set of systematically interconnected and interdependent economic, environmental and social concerns at different levels that firms are expected to address simultaneously” (p. 299).38Hahn, T., Pinkse, J., Preuss, L. & Figge, F. Tensions in Corporate Sustainability: Towards an Integrative Framework. Journal of Business Ethics 127, 297-316 (2015). |

| Linneluecke and Griffiths (2013) | “[R]efers to firm engagement with social and environmental issues in additional [sic] to their economic activities” (p. 383).9Linnenluecke, M. K. & Griffiths, A. Firms and sustainability: Mapping the intellectual origins and structure of the corporate sustainability field. Global Environmental Change 23, 382–391 (2013). |

| Lozano et al. (2015) | “Corporate activities that proactively seek to contribute to sustainability equilibria, including the economic, environmental, and social dimensions of today, as well as their inter-relations within and throughout the time dimension while addressing the company’s system (including Operations and production, Management and strategy, Organisational systems, Procurement and marketing, and Assessment and communication); and its stakeholders” (p. 34).39Lozano, R. A Holistic Perspective on Corporate Sustainability Drivers. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 22, 32–44 (2015). |

| Montiel (2008) | There are two ways of defining and conceptualizing CS: – Ecological sustainability: primarily with the environmental dimension of business – Tridimensional construct: Includes environmental, economic, and social dimensions. (p. 254).16Montiel, I. Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 21, 245–269 (2008). |

| Montiel and Delgado-Ceballos (2014) | “[W]e propose using ‘corporate sustainability’ for the tridimensional construct” (p. 123).8Montiel, I. & Delgado-Ceballos, J. Defining and Measuring Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 27, 113–139 (2014). |

| Rasche et al. (2023) | “Corporate Sustainability focuses on managing and balancing an enterprise’s embeddedness in interrelated ecological, social and economic systems so that positive impact is created in the form of long-term ecological balance, social welfare and stakeholder value” ( p.8).40Rasche, A., Morsing, M., Moon, J. & Kourula, A. Corporate Sustainability – What It Is and Why It Matters. in Corporate Sustainability – Managing Responsible Business in a Globalised World Vol. 2 (eds Rasche, A., Morsing, M., Moon, J., & Kourula, A.) Ch. 1, 29-53 (Cambridge University Press, 2023). |

| Schaltegger and Burrit (2005) | “‘[C]orporate sustainability’ links the general approach of sustainability with sustainability at the corporate level” (p. 185).2 Schaltegger, S. & Burritt, R. Corporate Sustainability. The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 2005/2006., 336 (2005). |

| Steurer et al. (2005) | “For the business enterprise, SD means adopting business strategies and activities that meet the needs of the enterprise and its stakeholders today while protecting, sustaining and enhancing the human and natural resources that will be needed in the future” (p. 274).41Steurer, R., Langer, M. E., Konrad, A. & Martinuzzi, A. Corporations, Stakeholders and Sustainable Development I: A Theoretical Exploration of Business–Society Relations. Journal of Business Ethics 61, 263-281 (2005). |

| Van Marrewijk and Werre (2003) | “Corporate Sustainability […] refers to a company’s activities […] demonstrating the inclusion of social and environmental concerns in business operations and interactions with stakeholders (p. 107).42Van Marrewijk, M. & Werre, M. Multiple Levels of Corporate Sustainability. Journal of Business Ethics 44, 107-119 (2003). |

| Wilson (2003) | “[…] [C]orporate Sustainability is an alternative to the traditional growth and profit-maximization model. While corporate sustainability recognizes that corporate growth and profitability are important, it also requires the corporation to pursue social goals, specifically those relating to sustainable development […]” (n.p.).43Wilson, M. Corporate Sustainability: What is it and where does it come from?, Accessed on 07.01, 2025, <https://iveybusinessjournal.com/publication/corporate-sustainability-what-is-it-and-where-does-it-come-from/> (2003). |

In the academic debate, various other terms are used to refer to CS. These include ecological sustainability, environmental/social sustainability, environmental responsibility, CSR (corporate) sustainable development, sustainability, sustaincentrism, sustaincentric orientation, business sustainability, and sustainable corporation/organization.9Linnenluecke, M. K. & Griffiths, A. Firms and sustainability: Mapping the intellectual origins and structure of the corporate sustainability field. Global Environmental Change 23, 382–391 (2013).44Bansal, P. & DesJardine, M. R. Business sustainability: It is about time. Strategic Organization 12, 70–78 (2014).17Burbano, V. C., Delmas, M. A. & Cobo, M. J. The Past and Future of Corporate Sustainability Research. Organization & Environment (2023). Corresponding examples can be found in Table 2.

Table 2: CS-related Definitions with different terms

| Author(s) | Term | Definition |

| Bansal (2005) | Corporate Sustainable Development | “Organizations must apply these principles [annotation: economic prosperity, social equity, and environmental integrity] to their products, policies, and practices in order to express sustainable development” (p. 199).26Bansal, P. Evolving sustainably: a longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strategic Management Journal 26, 197-218 (2005). |

| Bansal and DesJardine (2014) | Business Sustainability | “[B]usiness sustainability can be defined as the ability of firms to respond to their short-term financial needs without compromising their (or others’) ability to meet their future needs [emphasis added by the authors]” (p. 71).44Bansal, P. & DesJardine, M. R. Business sustainability: It is about time. Strategic Organization 12, 70–78 (2014). |

| Bowen (1953) | Social responsibility | “[…] [O]bligations of businessmen to pursue those policies, to make those decisions, or to follow those lines of action which are desirable in terms of objectives and values of our society” (p. 6).45Bowen, H. R. Social Responsibilities of the Businessman. (University of Iowa Press, 1953). |

| Elkington (1997) | Triple Bottom Line, Sustainable Development | “Sustainable development involves the simultaneous pursuit of economic prosperity, environmental quality, and social equity. Companies aiming for sustainability need to perform not against a single, financial bottom line but against the triple bottom line” (p. 397).25Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks. (Capstone Publishing, 1997). |

| Gladwin et al. (1995) | Sustaincenterism | “ […] [P]rocess of achieving human development […] in an inclusive, connected, equitable, prudent, and securemanner [emphasis added by the authors]” (p. 878).24Gladwin, T. N., Kennelly, J. J. & Krause, T.-S. Shifting Paradigms for Sustainable Development: Implications for Management Theory and Research. Academy of Management Review 20, 874-907 (1995). |

| Hall and Vredenburg (2003) | Sustainable Development Innovation | “[…] [S]ustainable development innovation (SDI) must incorporate the added constraints of social and environmental pressures as well as consider future generations” (p. 61).46Hall, J. & Vredenburg, H. The Challenges of Innovating for Sustainable Development. MIT Sloan Management Review 45, 61-68 (2003). |

| Hart and Millstein (2003) | Sustainable Enterprise | “A sustainable enterprise, therefore, is one that contributes to sustainable development by delivering simultaneously economic, social, and environmental benefits – the so-called triple bottom line (p. 56).47Hart, S. L. & Milstein, M. B. Creating sustainable value. Academy of Management Perspectives 17, 56-67 (2003). |

| Marshall and Brown (2003) | Environmentally Sustainable Organization | “In terms of environmental sustainability, an ‘ideal’ sustainable organization will not use natural resources faster than the rates of renewal, recycling, or regeneration of those resources” (p. 22).48Marshall, R. S. & Brown, D. The Strategy of Sustainability: A Systems Perspective on Environmental Initiatives. California Management review 46, 101-126 (2003). |

| Shrivastava (1995) | Ecological Sustainability Development | “I suggest four ways that corporations can contribute that corporations can contribute to ecological sustainability through (a) total quality environmental management(TQEM), (b) ecologically sustainable competitive strategies, (c) technology-for-nature swaps, and (d) the reduction of the impact that populations have on ecosystems [emphasis added by the author]” (p. 938).49Shrivastava, P. The Role of Corporations in Achieving Ecological Sustainability. Academy of Management Review 20, 936-960 (1995). |

| Valente (2012) | Sustaincentric orientation | “A sustaincentric orientation is defined as an ongoing process of equitably including a highly interconnected set of seemingly incompatible social, ecological, and economic systems through collaborative theorization of coordinated approaches that harness the collective cognitive and operational capabilities of multiple local and global social, ecological, and economic stakeholders operating as a unified network or system” (p. 586).50Valente, M. Theorizing Firm Adoption of Sustaincentrism. Organization Studies 33, 563-591 (2012). |

| WCED (1987) | Sustainable Development | “Sustainable development seeks to meet the needs and aspirations of the present without compromising the ability to meet those of the future” (n.p.).5Brundtland, G. H. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (Catalogue No. A/42/427, Geneva, 1987). |

An analysis of the various definitions reveals that different approaches are used in defining CS.8Montiel, I. & Delgado-Ceballos, J. Defining and Measuring Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 27, 113–139 (2014). The first approach is the three-dimensional approach, which addresses ecological, economic, and social aspects, such as Dyllick and Hockerts (2002) or Hahn and Figge (2011). The second one is the bi-dimensional identifies CS in terms of the social and ecological dimensions, such as Hall and Vredenburg (2003) (see Table 2). The third one is the one-dimensional approach uses CS synonymously for environmental issues, such as Montiel’s (2008) or Shrivastava’s (1995) definitions of ‘Ecological Sustainability8Montiel, I. & Delgado-Ceballos, J. Defining and Measuring Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 27, 113–139 (2014).16Montiel, I. Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 21, 245–269 (2008).46Hall, J. & Vredenburg, H. The Challenges of Innovating for Sustainable Development. MIT Sloan Management Review 45, 61-68 (2003). Van Marrewijk (2003) posits that the term ‘CS’ can assume different meanings depending on the specific area and type of application.42Van Marrewijk, M. & Werre, M. Multiple Levels of Corporate Sustainability. Journal of Business Ethics 44, 107-119 (2003).51van Marrewijk, M. Concepts and Definitions of CSR and Corporate Sustainability: Between Agency and Communion. Journal of Business Ethics 44, 95–105 (2003). Definitions can differ, for example, in terms of how sustainability dimensions are considered.10 Meuer, J., Koelbel, J. & Hoffmann, V. H. On the Nature of Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 33, 319–341 (2020). All three approaches have been used in research, although much of the literature, particularly at the beginning of the research debate, has strongly focused on the environmental dimensions.8Montiel, I. & Delgado-Ceballos, J. Defining and Measuring Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 27, 113–139 (2014). Further information on the development of the academic debate is provided in Chapter 2.2

The definitions listed above in Table 1 and Table 2 can be divided into those published in practitioner journals and those published in academic ones. While practitioner definitions try to provide guidelines on how organisations can integrate CS, academics use broader and more complex definitions.8Montiel, I. & Delgado-Ceballos, J. Defining and Measuring Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 27, 113–139 (2014). Examples of practitioner definitions include those of Marshall and Brown (2003), Hart and Milstein (2003) or Markevich (2009).47Hart, S. L. & Milstein, M. B. Creating sustainable value. Academy of Management Perspectives 17, 56-67 (2003).48Marshall, R. S. & Brown, D. The Strategy of Sustainability: A Systems Perspective on Environmental Initiatives. California Management review 46, 101-126 (2003).52Markevich, A. The Evolution Of Sustainability. MIT Sloan Management Review 51, 13-14 (2009). Academic definitions include Gladwin et al. (1995), Shrivastava (1995) and Bansal (2005).24Gladwin, T. N., Kennelly, J. J. & Krause, T.-S. Shifting Paradigms for Sustainable Development: Implications for Management Theory and Research. Academy of Management Review 20, 874-907 (1995).26Bansal, P. Evolving sustainably: a longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strategic Management Journal 26, 197-218 (2005).49Shrivastava, P. The Role of Corporations in Achieving Ecological Sustainability. Academy of Management Review 20, 936-960 (1995). In their definitions, authors such as Gladwin et al. (1995), Shrivastava (1995), and Elkington (1997) attempt to specify certain criteria or steps that companies should fulfil in order to achieve sustainable development.24Gladwin, T. N., Kennelly, J. J. & Krause, T.-S. Shifting Paradigms for Sustainable Development: Implications for Management Theory and Research. Academy of Management Review 20, 874-907 (1995).25Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks. (Capstone Publishing, 1997).49Shrivastava, P. The Role of Corporations in Achieving Ecological Sustainability. Academy of Management Review 20, 936-960 (1995). These definitions are more descriptive than those presented in Table 1. According to Meuer et al. (2020), a classification of different definitions according to ‘level of ambition’, ‘level of integration’ and ‘specificity of sustainability’ is also possible.10 Meuer, J., Koelbel, J. & Hoffmann, V. H. On the Nature of Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 33, 319–341 (2020). The ‘level of ambition’ refers to “how ambitious firms should be in setting certain objectives” (p. 328) according to the respective definition of CS.10 Meuer, J., Koelbel, J. & Hoffmann, V. H. On the Nature of Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 33, 319–341 (2020). The ‘level of integration’ criterion refers to the extent to which “firms should integrate sustainability into their operations” (p. 328).10 Meuer, J., Koelbel, J. & Hoffmann, V. H. On the Nature of Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 33, 319–341 (2020). The last criterion, ‘specificity of sustainability’, considers to which extent the different definitions include the four dimensions, “[…] the environmental, the social, the economic and the intergenerational […]” (p. 328), based on the WCED definition of sustainable development.10 Meuer, J., Koelbel, J. & Hoffmann, V. H. On the Nature of Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 33, 319–341 (2020). However, the fourth dimension, the intergenerational one, is hardly mentioned in the existing definitions.10 Meuer, J., Koelbel, J. & Hoffmann, V. H. On the Nature of Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 33, 319–341 (2020). Instead, the focus is on considering the ecological, social and economic dimensions. Derived from and considering these categories, Meuer et al. (2020) classify the studied definitions into two groups: (1) CS as a type of business practice that is part of the business model or strategy and (2) CS as a new management paradigm and a way of doing business.10 Meuer, J., Koelbel, J. & Hoffmann, V. H. On the Nature of Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 33, 319–341 (2020).

Although no definition is commonly used, most seem to point in similar directions. According to Figge and Hahn (2011), there seems to be a consensus that CS considers ecological, social and economic aspects equally.7Hahn, T. & Figge, F. Beyond the Bounded Instrumentality in Current Corporate Sustainability Research: Toward an Inclusive Notion of Profitability. Journal of Business Ethics 104, 325–345 (2011). This consensus is particularly confirmed by the definitions listed in Table 1. The presented definitions are a small selection to illustrate the variety of existing ones. Building upon the three reviews mentioned above, the publications and definitions listed were compared and supplemented by further definitions or authors mentioned more than once during the literature search. However, the many definitions also clarify that CS is still an evolving and relatively new concept.21Ashrafi, M., Magnan, G. M., Adams, M. & Walker, T. R. Understanding the Conceptual Evolutionary Path and Theoretical Underpinnings of Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Sustainability. Sustainability 12, 760 (2020).

1.2 Related Concepts

Regarding the question of what companies are responsible for and the relationship between business and society, several theoretical frameworks are available that provide a conceptual framework for these ambitions.4Bansal, P. & Song, H.-C. Similar But Not the Same: Differentiating Corporate Sustainability from Corporate Responsibility. Academy of Management Annals 11, 105–149 (2017).53Schwartz, M. S. & Carroll, A. B. Integrating and Unifying Competing and Complementary Frameworks. Business & Society 47, 148-186 (2008). CS is a holistic approach frequently associated with related concepts such as CG, CSR, CC, or Corporate Philanthropy (CP).27Ashrafi, M., Adams, M., Walker, T. R. & Magnan, G. How corporate social responsibility can be integrated into corporate sustainability: a theoretical review of their relationships. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 25, 672-682 (2018).53Schwartz, M. S. & Carroll, A. B. Integrating and Unifying Competing and Complementary Frameworks. Business & Society 47, 148-186 (2008).54Dissanayake, H. et al. A systematic literature review on the relationship between corporate governance and corporate sustainability. Environment, Development and Sustainability (2024).55Oliveira, U. R. d., Menezes, R. P. & Fernandes, V. A. A systematic literature review on corporate sustainability: contributions, barriers, innovations and future possibilities. Environment, Development and Sustainability 26, 3045–3079 (2024).56Lee, T. H. How firms communicate their social roles through corporate social responsibility, corporate citizenship, and corporate sustainability: An institutional comparative analysis of firms’ social reports. International Journal of Strategic Communication 15, 214-230 (2021). All these terms are frequently associated with the responsibility of companies in different ways, mostly focused on the interconnection with their social roles.56Lee, T. H. How firms communicate their social roles through corporate social responsibility, corporate citizenship, and corporate sustainability: An institutional comparative analysis of firms’ social reports. International Journal of Strategic Communication 15, 214-230 (2021).57Morgan, G., Ryu, K. & Mirvis, P. Leading corporate citizenship: governance, structure, systems. IEEE Engineering Management Review 9, 39-49 (2009). Concepts associated with the interconnection of the environmental dimensions are, however, primarily directed towards environmental management systems and measuring the impact on the environment.8Montiel, I. & Delgado-Ceballos, J. Defining and Measuring Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 27, 113–139 (2014).

This link between the corporation’s responsibilities and their perceived role within society has played a central role in more and more companies since the beginning of the 20th century as social commitment and a sense of responsibility for the impact of their business activities are increasingly becoming part of (external) expectations.58Wagenhöfer, L. & Erpf, P. Corporate Philanthropy und Sozialer Druck in KMU–Ein konzeptuelles Wirkungsmodell. (2021). “Today’s corporations are increasingly implementing responsible behaviours as they pursue profit-making activities” (p. 59).59Camilleri, M. A. Corporate sustainability and responsibility: creating value for business, society and the environment. Asian Journal of Sustainability and Social Responsibility 2, 59-74 (2017). In contrast to the holistic CS concept, concepts such as CSR, CC or CP focus on the fulfilment of social responsibility, whereas the CG concept addresses the control mechanisms necessary to implement all the other concepts.54Dissanayake, H. et al. A systematic literature review on the relationship between corporate governance and corporate sustainability. Environment, Development and Sustainability (2024).56Lee, T. H. How firms communicate their social roles through corporate social responsibility, corporate citizenship, and corporate sustainability: An institutional comparative analysis of firms’ social reports. International Journal of Strategic Communication 15, 214-230 (2021).

1.2.1 Corporate Governance

CG and CS are two key concepts in modern corporate management.54Dissanayake, H. et al. A systematic literature review on the relationship between corporate governance and corporate sustainability. Environment, Development and Sustainability (2024). CG focuses on the legal and structural framework governing corporate control and management, while CS emphasises integrating sustainability into the corporate strategy. Both concepts are relevant for companies seeking long-term success and lay the foundation for sustainable corporate processes and activities.54Dissanayake, H. et al. A systematic literature review on the relationship between corporate governance and corporate sustainability. Environment, Development and Sustainability (2024). CG sets the rules for operations, business relationships, and decision-making, including corporate strategy, risk management, goal setting, performance measurement, and ensuring effective audit and accounting mechanisms. It provides a framework for controlling and managing the organisation through its processes, structures, and established systems and also monitors, regulates, and directs all business activities.54Dissanayake, H. et al. A systematic literature review on the relationship between corporate governance and corporate sustainability. Environment, Development and Sustainability (2024).60E-Vahdati, S., Zulkifli, N. & Zakaria, Z. Corporate governance integration with sustainability: a systematic literature review. Corporate Governance: The international journal of business in society 19, 255-269 (2019).61 Shailer, G. Corporate Governance. in Encyclopedia of Business and Professional Ethics (eds Poff, D. & Michalos, A.) 1-6 (Springer International Publishing, 2018).62Owen, N. J. The failure of HIH Insurance Volume I A corporate collapse and its lessons. Vol. 1 (The HIH Royal Commission, 2003).These guidelines consequently serve as a foundation for the management of the company and the decision-making processes.62Owen, N. J. The failure of HIH Insurance Volume I A corporate collapse and its lessons. Vol. 1 (The HIH Royal Commission, 2003). Most established governance structures within a company are based on or aligned with national or international guidelines such as the G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance – the global standard – or the German Corporate Governance Code. Like Germany, most countries have their own Code of Corporate Governance (an overview of several codes can be found here: https://www.ecgi.global/publications/codes).63 OECD. Corporate governance, Accessed on 03.01, 2025, <https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/corporate-governance.html> (n.d.).64ECGI. Codes, Accessed on 03.01, 2025, <https://www.ecgi.global/publications/codes> (n.d.). Generally, CG structures are based on transparency, accountability, responsibility, and fairness.54Dissanayake, H. et al. A systematic literature review on the relationship between corporate governance and corporate sustainability. Environment, Development and Sustainability (2024).65Aras, G. & Crowther, D. Governance and sustainability. Management Decision 46, 433-448 (2008).

In recent years, sustainability has become an increasingly significant concern for businesses, and thus, there is a need to integrate sustainability into management and anchor it in the corporate strategy. This transformation requires changes at all company levels, including processes, products, services, and the internal corporate culture.66Du Plessis, J. J., Hargovan, A. & Bagaric, M. Principles of Contemporary Corporate Governance. 2 edn, (Cambridge University Press, 2012). Adapting and adjusting governance structures following this shift is becoming increasingly apparent as established mechanisms significantly impact how sustainability is achieved and implemented within the company.66Du Plessis, J. J., Hargovan, A. & Bagaric, M. Principles of Contemporary Corporate Governance. 2 edn, (Cambridge University Press, 2012). Consequently, a growing convergence between CS and CG, known as ‘sustainable corporate governance’, links both concepts. Companies are, therefore, organising the control mechanisms of their processes so that profit and financial interests are taken into account while at the same time changing the processes to reflect the principles of sustainability, which reflect the values of the company and its stakeholders.66Du Plessis, J. J., Hargovan, A. & Bagaric, M. Principles of Contemporary Corporate Governance. 2 edn, (Cambridge University Press, 2012). This development is emphasized by the recently introduced Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), which draws attention to the growing interconnection between CG and CS.68EU Commission & Directorate-General for Financial Stability, F. S. a. C. M. U. (FISMA, 2023). While the CSRD does not require companies to implement sustainable corporate governance, it does mandate that companies disclose information about their existing governance structures transparently. For example, the general European Sustainability Reporting Standard (ESRS) 2, Appendix A, Application Requirements, Section 2, ‘Governance’, which is mandatory for all companies, defines several disclosure requirements relating to CG. These include GOV-1, ‘The role of the administrative, management and supervisory bodies’, and GOV-2, ‘Information provided to and sustainability matters addressed by the undertaking’s administrative, management and supervisory bodies.68EU Commission & Directorate-General for Financial Stability, F. S. a. C. M. U. (FISMA, 2023). This encourages the integration of sustainability into existing corporate governance frameworks.69Sandhövel, M. & Münch, C. CSRD: Sustainable Governance. (2024). Consequently, a well-structured CG supports the successful integration of sustainability into a company and can help to ensure that a company is led and organized responsibly and sustainably. A poorly designed CG, on the other hand, can threaten the firm’s long-term success, existence, and sustainability performance.70Rasche, A. Corporate Governance and Sustainability. in Corporate Sustainability Managing Responsible Business in a Globalised world Vol. 2 (eds Rasche, A., Morsing, M., Moon, J., & Kourula, A.) Ch. 15, 297-314 (Cambridge University Press, 2023). More information on CG is provided in the corresponding WIKI entry.

1.2.2 Corporate Social Responsibility

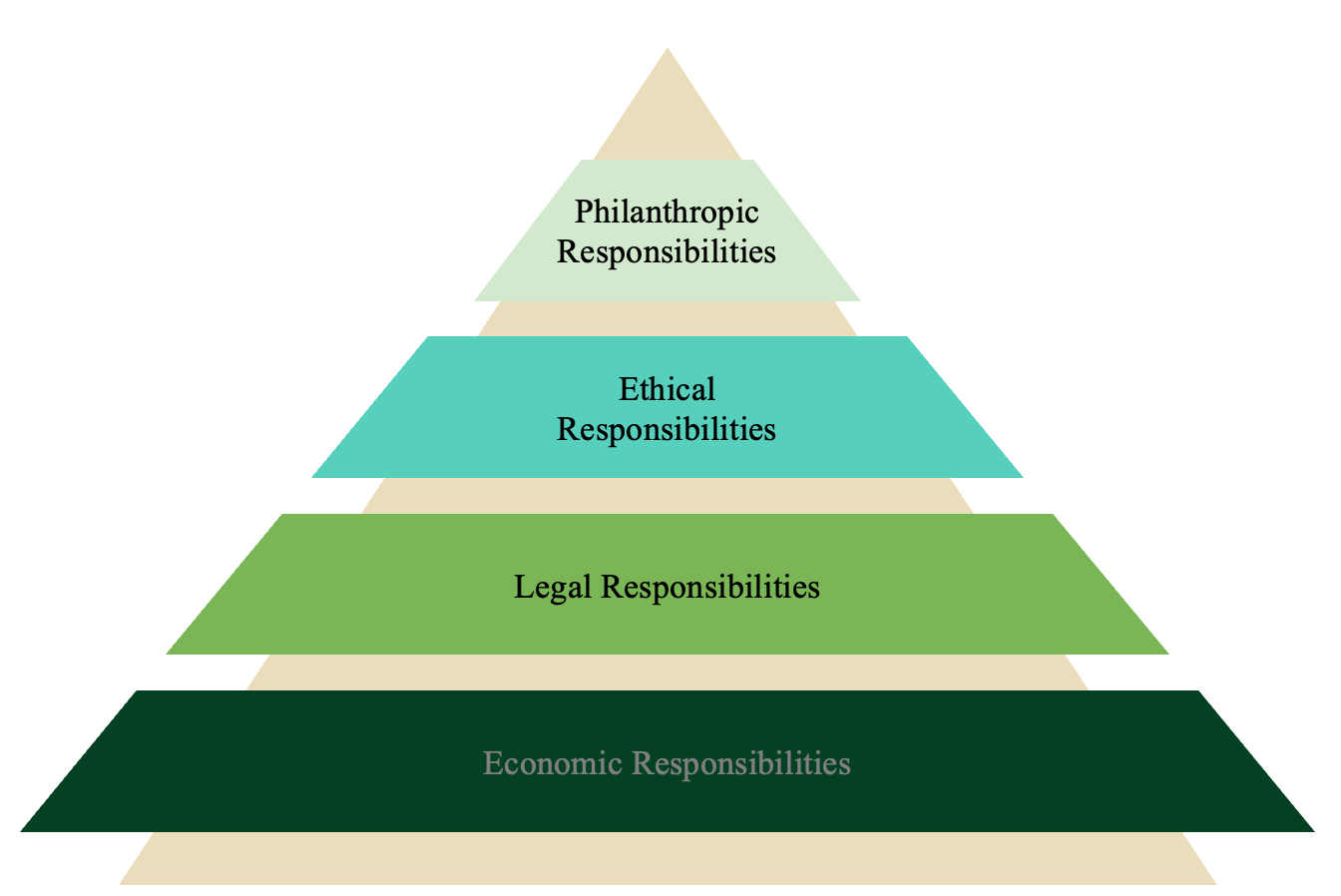

Since the 1950s, the CSR concept has been addressing the role and responsibility of companies in and for society.71Carroll, A. B. A History of Corporate Social Responsibility: Concepts and Practices. in The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility Ch. 2, 19 – 46 (Oxford University Press, 2008).72Carroll, A. B. A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model of Corporate Performance. The Academy of Management Review 4, 497 (1979). Carroll (1979) defines CSR such that “the social responsibility of business encompasses the economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary expectations that society has of organizations at a given point in time” (p. 500).61 Shailer, G. Corporate Governance. in Encyclopedia of Business and Professional Ethics (eds Poff, D. & Michalos, A.) 1-6 (Springer International Publishing, 2018). To this day, this definition is one of the most frequently quoted ones.16Montiel, I. Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 21, 245–269 (2008).72Carroll, A. B. A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model of Corporate Performance. The Academy of Management Review 4, 497 (1979). It is visualized in Carroll’s (1991) ‘Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibilities’ (Figure 2), which has been regarded as the basis for CSR implementation since the early 1990s and categorises CSR into four main areas of responsibility: economic, legal, ethical and discretionary (philanthropic) responsibilities.22Schaltegger, S. Von CSR zu Corporate Sustainability. in Corporate Social Responsibility in kommunalen Unternehmen – Wirtschaftliche Betätigung zwischen öffentlichem Auftrag und gesellschaftlicher Verantwortung (eds Sandberg, B. & Lederer, K.) 187-199 (VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2011).72Carroll, A. B. A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model of Corporate Performance. The Academy of Management Review 4, 497 (1979).73Carroll, A. B. The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility: Toward the Moral Management of Organizational Stakeholders. Business Horizons 34, 39-48 (1991). Carroll (1979) emphasises that these categories are not mutually exclusive and that all corporate activities can be assigned to one or more categories.72Carroll, A. B. A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model of Corporate Performance. The Academy of Management Review 4, 497 (1979).

CSR refers to the voluntary integration of social and environmental concerns into a company’s business activities and stakeholder interactions.22Schaltegger, S. Von CSR zu Corporate Sustainability. in Corporate Social Responsibility in kommunalen Unternehmen – Wirtschaftliche Betätigung zwischen öffentlichem Auftrag und gesellschaftlicher Verantwortung (eds Sandberg, B. & Lederer, K.) 187-199 (VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2011).74 Europäische Kommission: Generaldirektion Beschäftigung, S. u. I. Europäische Rahmenbedingungen für die soziale Verantwortung der Unternehmen – Grünbuch. (2001). While CSR initially appeared to focus solely on social issues, it is now widely recognized as encompassing environmental issues that impact the corporation’s surroundings.22Schaltegger, S. Von CSR zu Corporate Sustainability. in Corporate Social Responsibility in kommunalen Unternehmen – Wirtschaftliche Betätigung zwischen öffentlichem Auftrag und gesellschaftlicher Verantwortung (eds Sandberg, B. & Lederer, K.) 187-199 (VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2011).40Rasche, A., Morsing, M., Moon, J. & Kourula, A. Corporate Sustainability – What It Is and Why It Matters. in Corporate Sustainability – Managing Responsible Business in a Globalised World Vol. 2 (eds Rasche, A., Morsing, M., Moon, J., & Kourula, A.) Ch. 1, 29-53 (Cambridge University Press, 2023). CSR focuses on voluntary actions beyond legal obligations to benefit society and the environment.74 Europäische Kommission: Generaldirektion Beschäftigung, S. u. I. Europäische Rahmenbedingungen für die soziale Verantwortung der Unternehmen – Grünbuch. (2001). A key issue of CSR is the responsibility of companies.40Rasche, A., Morsing, M., Moon, J. & Kourula, A. Corporate Sustainability – What It Is and Why It Matters. in Corporate Sustainability – Managing Responsible Business in a Globalised World Vol. 2 (eds Rasche, A., Morsing, M., Moon, J., & Kourula, A.) Ch. 1, 29-53 (Cambridge University Press, 2023). CSR is often perceived as an approach that focuses on a company’s management practices and thus adopts an application-oriented perspective.22Schaltegger, S. Von CSR zu Corporate Sustainability. in Corporate Social Responsibility in kommunalen Unternehmen – Wirtschaftliche Betätigung zwischen öffentlichem Auftrag und gesellschaftlicher Verantwortung (eds Sandberg, B. & Lederer, K.) 187-199 (VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2011).40Rasche, A., Morsing, M., Moon, J. & Kourula, A. Corporate Sustainability – What It Is and Why It Matters. in Corporate Sustainability – Managing Responsible Business in a Globalised World Vol. 2 (eds Rasche, A., Morsing, M., Moon, J., & Kourula, A.) Ch. 1, 29-53 (Cambridge University Press, 2023). In recent years, the convergence of CSR and CS has become apparent.4,40,51van Marrewijk, M. Concepts and Definitions of CSR and Corporate Sustainability: Between Agency and Communion. Journal of Business Ethics 44, 95–105 (2003).40Rasche, A., Morsing, M., Moon, J. & Kourula, A. Corporate Sustainability – What It Is and Why It Matters. in Corporate Sustainability – Managing Responsible Business in a Globalised World Vol. 2 (eds Rasche, A., Morsing, M., Moon, J., & Kourula, A.) Ch. 1, 29-53 (Cambridge University Press, 2023). While CS originally emphasized environmental concern and later expanded to include social issues, CSR has taken the other trajectory. Initially centred on social issues, scholars gradually began considering environmental aspects, albeit to a lesser extent than CS.16Montiel, I. Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 21, 245–269 (2008).40Rasche, A., Morsing, M., Moon, J. & Kourula, A. Corporate Sustainability – What It Is and Why It Matters. in Corporate Sustainability – Managing Responsible Business in a Globalised World Vol. 2 (eds Rasche, A., Morsing, M., Moon, J., & Kourula, A.) Ch. 1, 29-53 (Cambridge University Press, 2023).22Schaltegger, S. Von CSR zu Corporate Sustainability. in Corporate Social Responsibility in kommunalen Unternehmen – Wirtschaftliche Betätigung zwischen öffentlichem Auftrag und gesellschaftlicher Verantwortung (eds Sandberg, B. & Lederer, K.) 187-199 (VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2011). Both concepts strive to integrate the ecological, economic and social dimensions into the corporate strategy. A more profound discussion about the discourse of responsibility (CSR) and sustainability (CS) is found in Chapter 3.4.2. Further information on the CSR concept is provided in the corresponding WIKI entry.

1.2.3 Corporate Citizenship

The concept of CC emerged in the 1980s in the U.S. as companies sought to shed light on their voluntary community engagement in response to the growing social and economic challenges affecting their competitiveness.75Fifka, M. S. CSR- und Nachhaltigkeitsmanagement. Vol. 1 (Nomos, 2021). While this engagement remains voluntary, society increasingly expects companies to engage in activities beyond profit-making.76Carroll, A. B. The Four Faces of Corporate Citizenship. Business & Society Review (1998). Consequently, more and more companies implement CC strategies into their business activities.77Habisch, A. Corporate Citizenship Gesellschaftliches Engagement von Unternehmen in Deutschland. (Springer, 2003).78Crane, A., Matten, D. & Moon, J. The emergence of corporate citizenship: historical development and alternative perspectives. in Corporate Citizenship in Deutschland – Gesellschaftliches Engagement von Unternehmen. Bilanz und Perspektiven Vol. 2 (eds Backhaus-Maul, H., Biedermann, C., Nährlich, S., & Polterauer, J.) 64-91 (VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2010). In this way, CC defines the role of companies in society, emphasising activities that benefit communities and thus allow companies to act as good (corporate) citizens.79Carroll, A. B. Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Business & Society 38, 268-295 (1999).80Kruggel, A., Tiberius, V. & Fabro, M. Corporate citizenship: Structuring the research field. Sustainability 12, 5289 (2020). According to Carroll (1998), a ‘good corporate citizen’ is expected to be profitable, obey the law, engage in ethical behaviour, and give back through philanthropy.76Carroll, A. B. The Four Faces of Corporate Citizenship. Business & Society Review (1998). Philanthropic responsibility includes various social, educational, recreational, and cultural purposes.79Carroll, A. B. Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Business & Society 38, 268-295 (1999).80Kruggel, A., Tiberius, V. & Fabro, M. Corporate citizenship: Structuring the research field. Sustainability 12, 5289 (2020).81Matten, D. & Crane, A. Corporate citizenship: Toward an extended theoretical conceptualization. Academy of Management review 30, 166-179 (2005).

CC activities include non-economic social issues and often refer to specific programs or initiatives that address social and environmental issues.82Seberich, M., Schröder, K. & Fiedler, J. Corporate Citizenshio vom philanthropischen Außenseiter zum Kompetenzzentrum in nachhaltigen Unternehmen. (2024). External objectives may be pursued for the benefit of society, but companies may also support internal objectives such as employee retention or brand reputation.82Seberich, M., Schröder, K. & Fiedler, J. Corporate Citizenshio vom philanthropischen Außenseiter zum Kompetenzzentrum in nachhaltigen Unternehmen. (2024). The most common CC instruments include corporate volunteering, corporate foundations, corporate giving and cause-related marketing.31Sawczyn, A. Unternehmerische Nachhaltigkeit und wertorientierte Unternehmensführung: empirische Untersuchung der Unternehmen im HDAX. Vol. 4 (Dr. Kovač, 2011).56Lee, T. H. How firms communicate their social roles through corporate social responsibility, corporate citizenship, and corporate sustainability: An institutional comparative analysis of firms’ social reports. International Journal of Strategic Communication 15, 214-230 (2021). By doing so, CC aligns with the concept of CSR, addressing companies’ social and philanthropic responsibility.76Carroll, A. B. The Four Faces of Corporate Citizenship. Business & Society Review (1998).80Kruggel, A., Tiberius, V. & Fabro, M. Corporate citizenship: Structuring the research field. Sustainability 12, 5289 (2020).78Crane, A., Matten, D. & Moon, J. The emergence of corporate citizenship: historical development and alternative perspectives. in Corporate Citizenship in Deutschland – Gesellschaftliches Engagement von Unternehmen. Bilanz und Perspektiven Vol. 2 (eds Backhaus-Maul, H., Biedermann, C., Nährlich, S., & Polterauer, J.) 64-91 (VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2010).83De-Miguel-Molina, B., Chirivella-González, V. & García-Ortega, B. Corporate philanthropy and community involvement. Analysing companies from France, Germany, the Netherlands and Spain. Quality & Quantity 50, 2741-2766 (2016). While CC primarily focuses on societal contributions, CSR encompasses broader ethical and responsible actions while also including environmental aspects, albeit to a lesser extent than social ones.74 Europäische Kommission: Generaldirektion Beschäftigung, S. u. I. Europäische Rahmenbedingungen für die soziale Verantwortung der Unternehmen – Grünbuch. (2001).76Carroll, A. B. The Four Faces of Corporate Citizenship. Business & Society Review (1998).83De-Miguel-Molina, B., Chirivella-González, V. & García-Ortega, B. Corporate philanthropy and community involvement. Analysing companies from France, Germany, the Netherlands and Spain. Quality & Quantity 50, 2741-2766 (2016). In contrast to CC and CSR, CS takes a holistic approach, equally considering social, environmental and economic aspects and emphasizing the overall impact of a company’s activities.78Crane, A., Matten, D. & Moon, J. The emergence of corporate citizenship: historical development and alternative perspectives. in Corporate Citizenship in Deutschland – Gesellschaftliches Engagement von Unternehmen. Bilanz und Perspektiven Vol. 2 (eds Backhaus-Maul, H., Biedermann, C., Nährlich, S., & Polterauer, J.) 64-91 (VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2010).84Waddock, S. The development of corporate responsibility/corporate citizenship. Organization Management Journal 5, 29-39 (2008).85Andriof, J. & McIntosh, M. Introduction. in Perspectives on Corporate Citizenship (eds Andriof, J. & McIntosh, M.) 13-24 (Greenleaf Publishing Limited, 2017).86Van der Byl, C. A. & Slawinski, N. Embracing tensions in corporate sustainability: A review of research from win-wins and trade-offs to paradoxes and beyond. Organization & Environment 28, 54-79 (2015). Nevertheless, companies also use CC projects to support sustainability goals and implement measures that enable the adaptation of business activities.82Seberich, M., Schröder, K. & Fiedler, J. Corporate Citizenshio vom philanthropischen Außenseiter zum Kompetenzzentrum in nachhaltigen Unternehmen. (2024).84Waddock, S. The development of corporate responsibility/corporate citizenship. Organization Management Journal 5, 29-39 (2008).87Vorest AG. Was ist Corporate Citizenship – Definition, Accessed on 05.01, 2025, <https://csr-iso-26000.de/nachhaltigkeitsmanagement/corporate-citizenship/> (n.d.). This can include social initiatives throughout the supply chain, implementing measures to reduce CO2 emissions and plastics, and enhancing the organisation’s internal understanding of sustainability.82Seberich, M., Schröder, K. & Fiedler, J. Corporate Citizenshio vom philanthropischen Außenseiter zum Kompetenzzentrum in nachhaltigen Unternehmen. (2024). One relevant difference between the two concepts is the mandatory nature. While CC remains voluntary, CS is increasingly being made mandatory (e.g., through the CSRD).78Crane, A., Matten, D. & Moon, J. The emergence of corporate citizenship: historical development and alternative perspectives. in Corporate Citizenship in Deutschland – Gesellschaftliches Engagement von Unternehmen. Bilanz und Perspektiven Vol. 2 (eds Backhaus-Maul, H., Biedermann, C., Nährlich, S., & Polterauer, J.) 64-91 (VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2010).82Seberich, M., Schröder, K. & Fiedler, J. Corporate Citizenshio vom philanthropischen Außenseiter zum Kompetenzzentrum in nachhaltigen Unternehmen. (2024).,88 Nevertheless, the influence of CS on CC increases as, e.g., the materiality analysis carried out as part of the CSRD serves as the basis for CC measures in some DAX 40 companies.82Seberich, M., Schröder, K. & Fiedler, J. Corporate Citizenshio vom philanthropischen Außenseiter zum Kompetenzzentrum in nachhaltigen Unternehmen. (2024). Consequently, CC activities are becoming increasingly derived from sustainability-related topics within the core business operations of major corporations. Prominent examples of companies that have integrated CC into their official sustainability or corporate strategies include DHL, Merck, SAP, and Siemens.82Seberich, M., Schröder, K. & Fiedler, J. Corporate Citizenshio vom philanthropischen Außenseiter zum Kompetenzzentrum in nachhaltigen Unternehmen. (2024). Sustainability and the pursuit of CS can encourage companies to change their perception of themselves as corporate citizens and adapt their behaviour accordingly. The pressure to declare long-term sustainability as a corporate goal and thus to adapt the company holistically in this direction can also contribute to considering CC.88Haufe Online Redaktion. Nachhaltigkeitsberichterstattung: Ein Kompass im Labyrinth der Vorgaben und Anforderungen (2. Aufl.), Accessed on 06.01, 2025, <https://www.haufe.de/finance/jahresabschluss-bilanzierung/kompass-fuer-die-nachhaltigkeitsberichterstattung_188_565142.html> (2023).88-90 More information on the concept of CC can be found in the respective WIKI entry.

1.2.4 Corporate Philanthropy

Philanthropy is one of the oldest forms of corporations taking on social responsibility. People in business have practised philanthropy since the 17th century, but it is only in the last few decades that the concept, as known today, has gained significant relevance for companies.78Crane, A., Matten, D. & Moon, J. The emergence of corporate citizenship: historical development and alternative perspectives. in Corporate Citizenship in Deutschland – Gesellschaftliches Engagement von Unternehmen. Bilanz und Perspektiven Vol. 2 (eds Backhaus-Maul, H., Biedermann, C., Nährlich, S., & Polterauer, J.) 64-91 (VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2010).,91,92 As shown in Chapter 3.1.2.2, Carroll (1991) places philanthropic responsibility at the top of the Corporate Social Responsibility Pyramid, emphasizing the obligation of businesses towards society and describing the goal of philanthropy to improve society’s quality of life.72Carroll, A. B. A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model of Corporate Performance. The Academy of Management Review 4, 497 (1979).73Carroll, A. B. The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility: Toward the Moral Management of Organizational Stakeholders. Business Horizons 34, 39-48 (1991).,93

In line with this, CP can be seen as the highest level of a corporation’s social responsibility.78Crane, A., Matten, D. & Moon, J. The emergence of corporate citizenship: historical development and alternative perspectives. in Corporate Citizenship in Deutschland – Gesellschaftliches Engagement von Unternehmen. Bilanz und Perspektiven Vol. 2 (eds Backhaus-Maul, H., Biedermann, C., Nährlich, S., & Polterauer, J.) 64-91 (VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2010).,94 As a key aspect, CP focuses on doing good and giving something back to society, especially through ethical conduct, diversity initiatives or environmental protection. CP is expressed through “voluntary and unconditional transfers of cash or other assets by private firms for public purposes” (p. 344), including donations, corporate volunteering, and pro bono work.95 These activities seek positive societal (and environmental) change, often without expecting direct returns.93 However, scholars debate whether altruistic motives or profit motives drive CP.95 While the answer to this question may not be clear, companies today have little chance of being competitive if they do not act philanthropically.95 ‘Strategic philanthropy’ bridges CP and business strategy by addressing community issues that benefit the firm’s position.94Although a link between CS and CP has not yet been established, CP plays an important role in addressing socio-economic issues under the sustainability dimensions and ESG criteria, more precisely aligning with the ‘S’ and helping their local communities.93 See the corresponding WIKI entry on the concept of CP for more information.

1.2.5 The relationship between the different concepts summarised

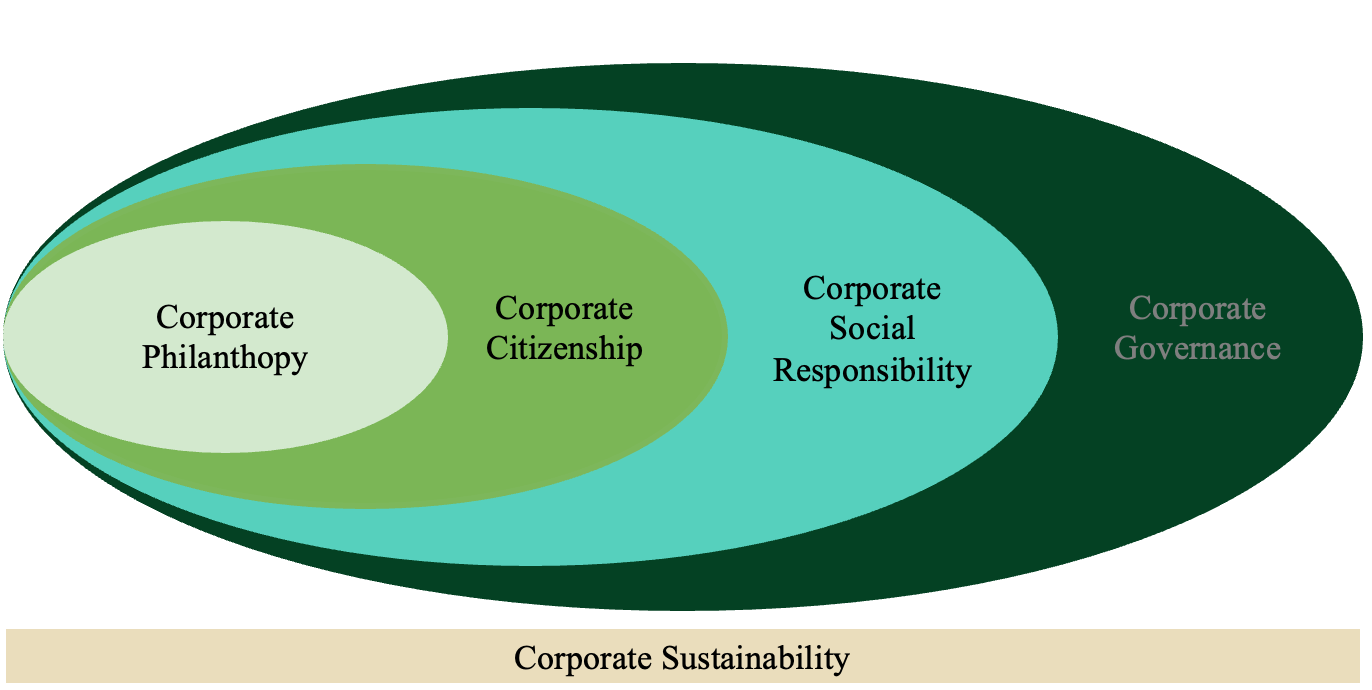

Figure 3 briefly illustrates the relationship between CS and the concepts described in this chapter. It is clear that CS influences and is influenced by all the concepts described. An important role is played by the CSR approach, which is moving closer and closer to CS and increasingly addresses environmental and social issues. The CC and CP concepts actively contribute to the implementation of CSR through practical measures and approaches. CG is necessary to implement the necessary strategies, measures, and objectives and integrate them into the company.

Table 3 summarises the different approaches, comparing their objectives, emergences, origins, main focuses and implementation.

Table 3: Differentiation of CS, CP, CC, CSR and CG

| Objective | Emergence | Origin | Main focus | Implementation | |

| CS | Balancing “[…] economic prosperity, environmental quality, and social equity”(p. 397).25Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks. (Capstone Publishing, 1997). | 1990s43Wilson, M. Corporate Sustainability: What is it and where does it come from?, Accessed on 07.01, 2025, <https://iveybusinessjournal.com/publication/corporate-sustainability-what-is-it-and-where-does-it-come-from/> (2003). | Environmentalism.4Bansal, P. & Song, H.-C. Similar But Not the Same: Differentiating Corporate Sustainability from Corporate Responsibility. Academy of Management Annals 11, 105–149 (2017).,96 10 Meuer, J., Koelbel, J. & Hoffmann, V. H. On the Nature of Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 33, 319–341 (2020). 25Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks. (Capstone Publishing, 1997). | Translating sustainability to the corporate context.2 Schaltegger, S. & Burritt, R. Corporate Sustainability. The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 2005/2006., 336 (2005). | Embedding in the corporate strategy and business model.54Dissanayake, H. et al. A systematic literature review on the relationship between corporate governance and corporate sustainability. Environment, Development and Sustainability (2024). |

| CG | Set of rules and processes to manage, control and direct all business activities.54Dissanayake, H. et al. A systematic literature review on the relationship between corporate governance and corporate sustainability. Environment, Development and Sustainability (2024). | Mid 1980s65Aras, G. & Crowther, D. Governance and sustainability. Management Decision 46, 433-448 (2008). | Anglo-American codes of good corporate governance65Aras, G. & Crowther, D. Governance and sustainability. Management Decision 46, 433-448 (2008). | Governance, Compliance54Dissanayake, H. et al. A systematic literature review on the relationship between corporate governance and corporate sustainability. Environment, Development and Sustainability (2024).65Aras, G. & Crowther, D. Governance and sustainability. Management Decision 46, 433-448 (2008). | Framework for controlling and managing the organisation is based on the principles of transparency, accountability, responsibility and fairness.54Dissanayake, H. et al. A systematic literature review on the relationship between corporate governance and corporate sustainability. Environment, Development and Sustainability (2024).60E-Vahdati, S., Zulkifli, N. & Zakaria, Z. Corporate governance integration with sustainability: a systematic literature review. Corporate Governance: The international journal of business in society 19, 255-269 (2019).61 Shailer, G. Corporate Governance. in Encyclopedia of Business and Professional Ethics (eds Poff, D. & Michalos, A.) 1-6 (Springer International Publishing, 2018).62Owen, N. J. The failure of HIH Insurance Volume I A corporate collapse and its lessons. Vol. 1 (The HIH Royal Commission, 2003).65Aras, G. & Crowther, D. Governance and sustainability. Management Decision 46, 433-448 (2008). |

| CSR | Aligning corporate action with societal interests beyond profit orientation.74 Europäische Kommission: Generaldirektion Beschäftigung, S. u. I. Europäische Rahmenbedingungen für die soziale Verantwortung der Unternehmen – Grünbuch. (2001). | 1950s71Carroll, A. B. A History of Corporate Social Responsibility: Concepts and Practices. in The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility Ch. 2, 19 – 46 (Oxford University Press, 2008). | Role and responsibility of companies in and for society.72Carroll, A. B. A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model of Corporate Performance. The Academy of Management Review 4, 497 (1979). | Fulfilling demands and expectations of society through voluntary activities.75Fifka, M. S. CSR- und Nachhaltigkeitsmanagement. Vol. 1 (Nomos, 2021). | Voluntarily integrating social and environmental concerns into business activities and stakeholder interactions.22Schaltegger, S. Von CSR zu Corporate Sustainability. in Corporate Social Responsibility in kommunalen Unternehmen – Wirtschaftliche Betätigung zwischen öffentlichem Auftrag und gesellschaftlicher Verantwortung (eds Sandberg, B. & Lederer, K.) 187-199 (VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2011).74 Europäische Kommission: Generaldirektion Beschäftigung, S. u. I. Europäische Rahmenbedingungen für die soziale Verantwortung der Unternehmen – Grünbuch. (2001). |

| CC | Acting as a good corporate citizen through activities that are beneficial for society.79Carroll, A. B. Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Business & Society 38, 268-295 (1999).80Kruggel, A., Tiberius, V. & Fabro, M. Corporate citizenship: Structuring the research field. Sustainability 12, 5289 (2020). ,79Linnenluecke, M. K. & Griffiths, A. Firms and sustainability: Mapping the intellectual origins and structure of the corporate sustainability field. Global Environmental Change 23, 382–391 (2013). | 1990s91 | Corporate Philanthropy and Community involvement53Schwartz, M. S. & Carroll, A. B. Integrating and Unifying Competing and Complementary Frameworks. Business & Society 47, 148-186 (2008). | Being a good corporate citizen, giving back to society, the environment and stakeholders.7Hahn, T. & Figge, F. Beyond the Bounded Instrumentality in Current Corporate Sustainability Research: Toward an Inclusive Notion of Profitability. Journal of Business Ethics 104, 325–345 (2011).6,98 | Programs or initiatives aimed at social and charitable goals align with business goals and values.82Seberich, M., Schröder, K. & Fiedler, J. Corporate Citizenshio vom philanthropischen Außenseiter zum Kompetenzzentrum in nachhaltigen Unternehmen. (2024). Corporate giving/volunteering/impact investing and activism82Seberich, M., Schröder, K. & Fiedler, J. Corporate Citizenshio vom philanthropischen Außenseiter zum Kompetenzzentrum in nachhaltigen Unternehmen. (2024). |

| CP | Doing well by doing good to improve competitiveness and image.93 | 1980s95 | Improving the society’s quality of life.93 | Doing well by doing good, focusing on specific charitable activities for society.93 | Voluntary cash transfer (such as donations, sponsoring, volunteering, pro bono work).58Wagenhöfer, L. & Erpf, P. Corporate Philanthropy und Sozialer Druck in KMU–Ein konzeptuelles Wirkungsmodell. (2021).95 |

2 Historical Development of CS

The following chapter examines the concept’s general development and the development within the academic debate.

2.1 The CS Concept

Within the past decades, sustainability has gained relevance, both in the practitioner field and in academia.10 Meuer, J., Koelbel, J. & Hoffmann, V. H. On the Nature of Corporate Sustainability. Organization & Environment 33, 319–341 (2020). The following chapter will give a brief overview of the historical background of CS and the development of the concept.