Author: Martin Rutter, April, 2025

1 Introduction

Infrastructure plays a crucial role in economic and social development, as it supports societal needs on a basic human level such as clean water, electricity, heating and general quality of life, and provides critical transport infrastructure for market needs such as roads, railways and ports.1 Governments traditionally provided the delivery of public infrastructure and services directly, but limited public capital and a shortage of management expertise have led to the adoption of alternative procurement methods.2-4 In addition, with projections indicating an increase of 67 percent by 2040 compared to 2015 values for infrastructure investments, a need for even greater investments may be needed to accommodate economic growth.1 In response to that, governments around the world have begun to tap into the private sectors capital and expertise to minimize public deficits5, reflecting a general trend toward the involvement of the private sector in the provision of infrastructure and services.6 Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) have emerged as one of the major alternative procurement methods for public procurement7,8, combining ‘the best of both worlds’ to create a favorable environment for delivering high-quality public infrastructures or services.3,9,10 On the one hand, these usually large-scale projects between public and private actors have become an important element in meeting the increasing demands of society11 and represent a crucial mechanism for organizing essential societal sectors, service provision, sustainable development, as well as innovative responses to major societal challenges.12 On the other hand, infrastructure projects often represent some of the largest financial commitments made by governments, which are fraught with economic uncertainties, risks, public versus private distributional issues, and environmental considerations.8 With the integration of sustainability considerations into public procurement and the introduction of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the existing challenges between the commercial interests of the private sector and the long-term sustainability goals of governments have also increased.13,14 In recent years, PPPs even have been emphasized as a tool for sustainable development.15 Under certain circumstances the various features of PPPs can contribute to generating efficient, affordable and sustainable infrastructure projects.16 Despite many mixed results in benefits and challenges, PPPs continue to be used for a wide variety of public infrastructure projects delivered around the world.10,17 PPPs have become increasingly popular, as there has been a steady growth in many developed countries such as the UK, Australia, Portugal, Spain, and are also widely used in developing countries as a means to build and operate their infrastructures.18

In the discipline of public administration, PPPs have been widely discussed with different debates and viewpoints.18There seems to be no consensus on how to define PPPs and what constitutes them in different disciplines, sectors, and even countries. Scholars highlight different research agendas and practitioners use PPPs as an alternative procurement method in different settings resulting in a wide diversity of approaches worldwide.9,18 Therefore, a better understanding of the concept of PPPs is needed, given that there are different interpretations and implementations. This study seeks to provide a comprehensive analysis of the existing PPP research from different disciplines, by integrating many insights from both academic and institutional sources. It aims to explore different elements that constitute PPPs, as well as critical debates, challenges and best practices, and potentially contribute to a better understanding of PPPs. It also aims to provide guidance to scholars for future research, and to practitioners looking to structure a PPP effectively and with sustainability considerations.

The study begins with an explanation of PPPs, their diverse definitions and differences from other procurement methods. It then provides a conceptual overview of various key elements and their possible best practices, as well as how to measure the success of a PPP. Practical implications for partners are then presented through a framework based on the theoretical conceptualization, combined with guidelines, tools and frameworks from (inter-)governmental organizations. Lastly, drivers and barriers to the implementation of PPPs are discussed. A particular emphasis lies in answering the key question “How are public-private partnerships conceptualized and implemented across various contexts and to what extent are sustainability considerations taken into account?”. By answering this question, this study contributes to a better understanding of PPPs, and shows recent advancements for sustainable development in PPPs.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Definition

The concept of PPP is interpreted in various ways lacking a clear standard definition; however, it is broadly described by many scholars as a long-term, collaborative relationship between the government and private actors.5,7,9,18-20 Many scholars or institutions added elements into a more detailed definition or changed it according to their central research focus. The OECD (2008) added more elements to their definition and defined PPPs as

“an agreement between the government and one or more private partners (which may include the operators and the financers) according to which the private partners deliver the service in such a manner that the service delivery objectives of the government are aligned with the profit objectives of the private partners and where the effectiveness of the alignment depends on a sufficient transfer of risk to the private partners” (p. 17).2

As for researchers, Grimsey and Lewis (2004) defined PPPs as “arrangements whereby private parties participate in, or provide support for, the provision of infrastructure, and a PPP project results in a contract for a private entity to deliver public infrastructure-based services” (p. 2).21 Iossa and Martimort (2014) wrote that under PPP, a “local authority or a central-government agency enters a long-term contract with a private supplier for the delivery of some service” (p. 5)6, in which the supplier takes on responsibilities for building, financing, managing and maintaining the infrastructure.6George et al. (2024) recently defined PPP as “organizational arrangements where relevant services or investments result from the joint action of public and private actors with varied degrees and types of engagement and responsibility” (p. 12).22

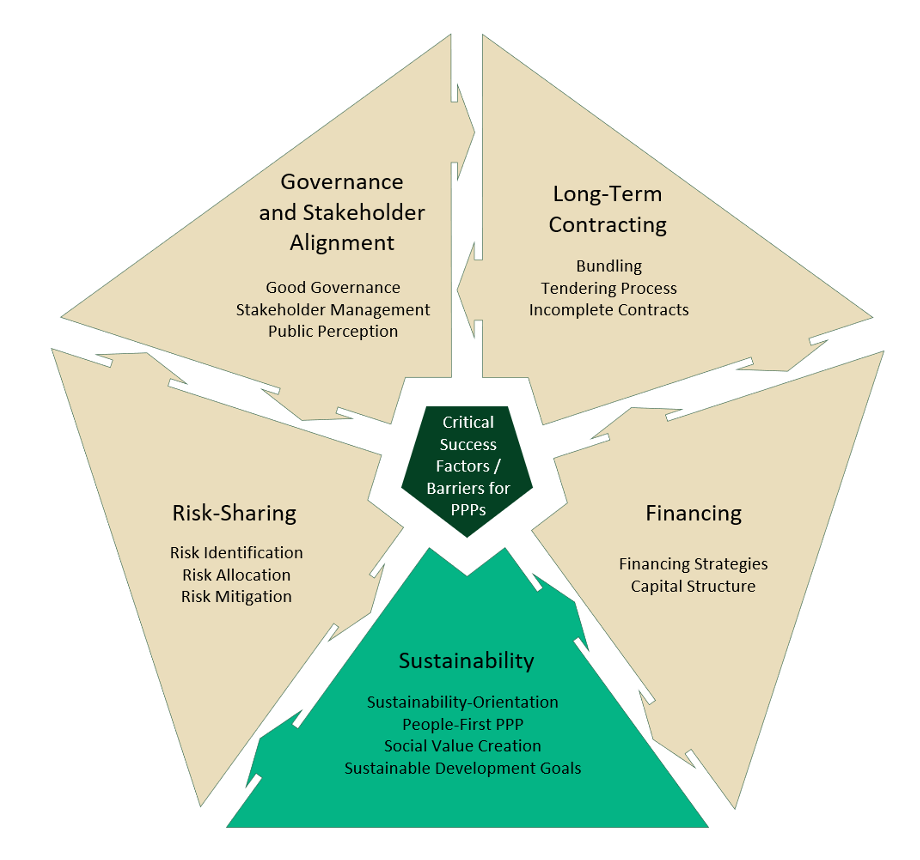

There seems to be no clarity around the definition2, as the interpretations have similarities, but vary slightly in scope and depth.5 PPPs are often seen as complex and eclectic18,23, that reflect flexibility and adaptability.9 While all researchers highlight the broad definition of a long-term, collaborative relationship between public and private actors to provide a service or infrastructure, the emphasis, detailing and weighting varies according to the key elements. Key elements of PPPs can be classified as governance and stakeholder involvement, long-term contracting, risk-sharing, financing and critical success factors.3,7,9,24,25 Further potential research topics can be classified under these elements. In recent years, sustainability has gained more and more significance in project delivery26, as it is of great interest in modern society.14 As a result, an increasing number of studies are focusing on sustainability in PPPs.25 Sustainability considerations have become a major part in PPPs; therefore, sustainability may be seen as a newly added element to the research on PPPs.

To understand the context in which PPPs are used and what is meant by providing a service or infrastructure, some researchers quoted Grimsey and Lewis (2004). They defined infrastructure as asset-based and refers to both economic infrastructure (key intermediate services for businesses and industries to enhance productivity/innovation such as roads, motorways, telecommunications, bridges, power, …) and social infrastructure (basic services for households to improve quality of life and welfare such as hospitals, housing, schools, water, sewage, …).21 Several reasons for the unclear definition can be identified.

2.1.1 Understanding the Diversity of PPPs

As mentioned before, PPP can be applied to a vast array of activities in delivering a service or infrastructure.20,21 While traditionally PPP has been widely used in the fields of infrastructure and public services, such as transportation, health, energy, water and sewage18, their scope has been extended across various sectors like IT services, accommodations, leisure facilities, prisons, military training, waste management, schools and hospitals and many more.6,7 Infrastructure involves many types and services, which also means that PPPs vary significantly in scope, complexity and structure.22,24 As Hodge and Greve (2007) mentioned, this wide diversity has resulted in a variety of broad and narrow definitions.9

Furthermore, PPP is an ever-changing field that has a different history in each country, changed over time and evolved throughout the world.9 The concept has adapted to constantly changing economic conditions and frequent policy changes.25 Global differences in economic (organizations and industries), political (regimes and voting systems), and cultural (diversity of societal problems) backgrounds contribute to the different approaches regarding PPPs forms and functions.22,27 As it seems, there is “no one single global ‘PPP model’” (p. 1108).20 For example, Cui et al. (2018)discovered in their literature review that there are evident differences in PPP project types and its implementation between developed and developing countries due to different abilities, environments and demands.25 Governments worldwide cover different risk-sharing, financing structures, transparency regulations and assumptions, on how to best deal with poor risk management or governance outcomes.28

Additionally, as stated before in the definition, PPP is viewed differentially by many and few agree on what PPP is.9Hodge and Greve (2017a) mentioned PPPs cover many meanings, such as being a single project or activity, a specific form of a project delivery arrangement, a symbol of the private sectors role in the economy, a governance tool to make use of the private sector or a phenomenon representing a change in project delivery.29 Thus, PPPs can be defined in various ways, come in several types and are used in different ways and situations.18 This results in a diversity in scholarly investigations covering multiple PPP research interests and differing across various disciplines.23 Hodge and Greve (2007) also described PPP as a ‘language game‘, where governments might use the term strategically to avoid opposition with words like ‘privatization‘ and ‘contracting out‘ that could result in different governmental views on PPPs.9

Lastly, the lack of a clear definition of PPPs can also be partly attributed to their overlap with other forms of public procurement. These forms share many close similarities, particularly in risk-sharing, service delivery and private sector involvement, adding more complexity to the distinction and definition. The next part covers this aspect and differentiates PPPs from other procurement methods.

2.1.2 Differentiation from other Procurement Methods

Most studies from the early 2000s aimed to clarify the difference between PPPs and traditional procurement methods.25According to Savas (2000), privatization is an act to reduce the role of the government or involve the private sector to meet the needs of people in a society; more specifically, relying more on the private sector and less on the government to improve public management.30 Traditional public procurement involves the public sector securing the full financing and paying the contractor as the work on the asset progresses.21 The public sector is fully responsible for delivering the public service.7 In that aspect, the opposite is full privatization, which refers to the complete transfer or sale of an asset, infrastructure, or service to a private entity.21 PPPs occupy a middle ground between traditional public procurement and full privatization.2 This middle ground is a broad space to fill and further types of procurement are in it, which may seem similar to PPPs.2,21 It is therefore important to clearly distinguish all forms of procurement.

In PPPs, a publicly owned organization, such as the government, and a privately owned organization or business, tend to pursue different operating and strategic goals3, but get together for a mutual goal, which drives them to build a partnership together in a dynamic and complex environment.18 Most times, the ownership of the infrastructure or asset goes to the private partner, but may later revert back to the public sector if it is an essential service or there is no obvious alternative use; for generic facilities with alternative use, the asset may remain in private ownership.6 Whether or not an activity or project is deemed a PPP in the first place depends on who bears the risk.2 A unique feature of PPPs is the allocation of risk5 and a generally greater risk premium.6 Another difference is that the cooperations through PPPs usually remain for a very long period of time3, typically in a closer cooperation based on trust, commitment17 and sharing at the heart of the partnership.18 Short-term projects are not PPPs.9,18 PPPs are characterized by longer procurement processes, and tendering processes of average around three years before the partnership starts.6,7 In that aspect, for public procurement there are mostly separate contracts for construction, maintenance and facility management, whereas under PPP those are typically bundled21 in one long-term contract.9,18 Traditional procurement typically involves the delivery of goods and services that are either completely public or private, whereas PPPs provide public or quasi-public goods and services to a third party (usually the society as a whole) that is usually not a direct client of either sector.3

As of Grimsey and Lewis (2004), PPPs may seem to have the same underlying principles as a joint venture in an open commercial environment.21 However, the main difference lies in the fact, that in joint ventures, the public and private partners jointly take a stake in equity for an infrastructure, while in PPPs the private partner takes full responsibility for tasks like development, operation and ownership.21 The focus in joint ventures lies in the co-production with external partners.17 Contracting out or rather outsourcing also involves the transfer of functions to an external private partner, but the focus lays on commissioning and more of a make-or-buy policy, rather than building long-term partnerships.18,31,32 As Grimsey and Lewis (2004) also stated, in concession agreements the government grants the private sector the right to design, construct, finance, renovate, operate and maintain facilities; the ownership may remain with the government or be transferred back to the government after the concession period.21 Concessions are rather a right or franchise to provide public services for a specified period of time.21 Leasing is similar in that aspect, but the government builds the asset or facility and leaves the operation and maintenance of it to the private firm.21 All these types differ from PPPs in the nature and degree of the risk transfer18, and are less of a direct partnership in the aspect of PPPs. It is important to note, that most PPPs are usually some type of concession or lease, but not restricted to it.21

PPPs widen the procurement process but there are many grey areas.21 As the different methods are intertwined, some joint ventures, outsourcing contracts, concessions and lease contracts can also be considered PPPs and vice versa, if the specific circumstances match. For example, an outsourcing arrangement where a private firm takes on a greater role in risk-sharing and long-term delivery of the service could also resemble a PPP. There are further types of PPPs that vary in the degree of private involvement, particularly in the extent of tasks transferred to the private partner, the separation of ownership and responsibility, and the sharing of risks between the public and private sector actors.3,7,10,13

2.1.3 Key Types

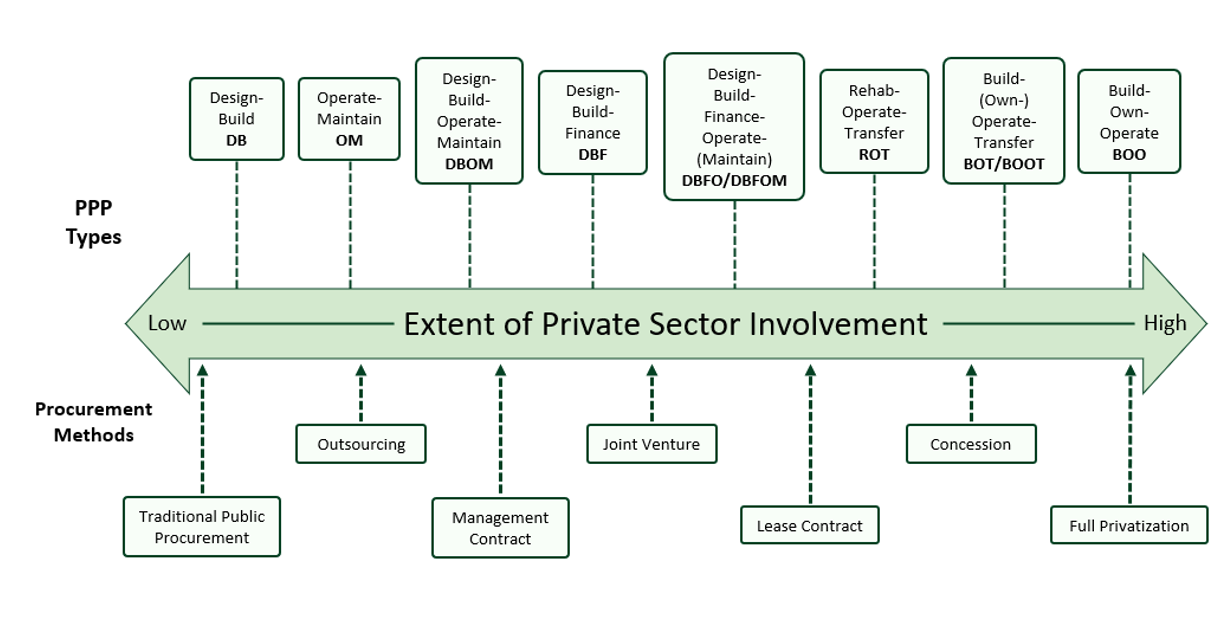

As mentioned before, PPPs can take on many different forms, however, there is a more specific continuum of common types that differentiate in the activities design, build, rehabilitate, own, operate, lease, finance, transfer and maintain.2,4,7,10,21 All forms and types may be classified under the ‘umbrella-term’ PPP.32 Figure 1 illustrates the possible public procurement methods and many of the following types of PPPs, based on the private sector involvement in a PPP.

Figure 1: Extent of Private Sector Involvement, own illustration, based on Roehrich et al. (2014); The World Bank (2017); Wojewnik-Filikowska and Wegrzyn (2019)10,16,33

There are various types for PPPs, which for example include more widespread types like BOT (Build-Operate-Transfer), BTO (Build-Transfer-Operate), BOO (Build-Own-Operate), BOOT (Build-Own-Operate-Transfer), DB (Design-Build), DBFO (Design-Build-Finance-Operate) and DBOM (Design-Build-Operate-Maintain), DBFOM (Design-Build-Finance-Operate-Maintain), OM (Operate-Maintain) and ROT (Rehabilitate-Operate-Transfer) and several more lesser used variations.2,7,10,16,34 Adoption varies among countries worldwide and very often depends on the country’s objectives, with DBFO being the most prominent in Europe, DBOM in North America and BOT/DBFO/DBOM relatively balanced in Asia.5,34

Key findings are that (1) most types of PPP account for bundling of Building (B) or Operation (O) of the infrastructure, but differ in the other aspects6, (2) the Design (D) types involve the whole development of the concept and specifications by the private partner, in which they bear more responsibilities and risks early on7,16, (3) all prominent Own (O) and Transfer (T) types involve higher private partner risks, as well as private ownership, concession agreements, and the consideration of transferring assets back to the government after the concession period7,10,16, (4) Operate (O) types typically involve user charge payment mechanisms, i.e. directly from the users of the facility through fees, tariffs or tolls16,25, (5) Finance (F) types require the private partner to finance all or part of the necessary capital expenditure without risks being limited to the equity of a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) company16, (6) types with Rehabilitation (R) and the type OM typically cover renewal and/or management of existing infrastructure.7,16

2.1.4 Theoretical Perspectives on PPPs

PPPs can be seen through a number of economic theories that help to explain several aspects, choices and challenges of PPP. As Cui et al. (2018) noted, researchers take on different theoretical perspectives to explore PPPs.25 The two foundational theories affecting PPPs are the principal-agent theory and the transaction cost theory.17 The principal-agent focuses on the principal (public sector) and the agent (private sector), and concerns incentive problems caused by information asymmetries.18 The transaction cost theory concerns optimal governance structure of transactions to minimize costs.18 In these theories opportunistic behavior plays an important role, which leads actors to use situations to their advantage, hence well-written contracts are important.35 Property rights theory deals with the incompleteness of PPP contracts.18 Other theories are the public choice theory and New Public Management concerning competition mechanisms, the stakeholder theory concerning the balance of stakeholders’ benefits, the network theory and governance theory examining the cooperation between public and private sectors and institutional theory exploring an institutional view on PPPs.18

2.2 Historical Background

The ‘linguistics of PPP’ began relatively recently, first being used by specialists in the 1970s with urban development and downtown renewal in the US.20,36 Looking even further back the possibility of financing infrastructure projects such as toll roads with private capital goes as far back as to Roman times; and even in the earlier 1800s countries used variations of co-financing and private financing as an important option for public infrastructure to provide roads, canals and railways.20

Due to budget deficits and increasing public debt burdens in the 1990s, the promise of private finance for large infrastructure was alluring for most governments.2 While their application in some parts of the world began in the early 1990s19, the UK was one of the first countries to formalize the idea of PPP into a policy preference, which was proposed as a Private Finance Initiative (PFI), to fund new infrastructure projects from the private sector due to the public fundings exceeding the national budget.20 PFI was the forerunner and later re-branded as PPP.18 After the financial crisis in 2007, some governments had to fill funding gaps and stimulate the economic recovery, in which they formally encouraged the private sector to invest in infrastructure construction.37 In the coming years, the PPP policy idea took off internationally and evolved into a global, much broader meaning covering many different aspects20, witnessing the development of several types of PPPs.19

In 2015 the United Nations (UN) introduced the 17 SDGs as part of the Agenda 2030, promoting a plan of action for the people, planet and prosperity38, in which many goals align with the scope of PPP projects in areas like infrastructure, sustainable cities and communities.39 With their adoption, PPPs have become even more prominent, encouraging sustainability as one of the key goals in partnering for infrastructure projects.26,40 In 2019 the UN presented PPP standards encouraging them as a tool for sustainable development, providing a focus on the people and reducing weaknesses in the implementation of the traditional PPPs.37,41

2.3 PPP Conceptualization

For a better understanding of what constitutes PPPs, it is essential to examine the previously mentioned key elements. The key elements – governance and stakeholder alignment, long-term contracting, risk-sharing, financing and sustainability – are the foundation of designing, implementing and evaluating PPP projects. A conceptual classification framework is shown in Figure 2 that summarizes the key elements and their most important components, which together are critical to the success of a PPP. The following section presents these key elements, their challenges and possible best practice solutions. Particularly, the best practices are a mix of critical success factors, theoretical models and PPP case examples found in the literature.

Figure 2: Conceptual Classification Framework, own illustration, inspired from Kwak et al. (2009))7

2.3.1 Public Governance and Stakeholder Alignment

When delivering infrastructure through PPPs, the stakeholders influence the outcomes, which gives rise to several issues on how the partnership is governed, who takes the lead and the nature of stakeholder involvement.40 Both partners are working together in a long-term relationship to achieve a common purpose.29 Strong relationships between the public and private sectors in PPP projects are therefore crucial to reduce misunderstandings or conflicts.42 Trust also plays a major role in the relationship between partners, as other control mechanisms, such as stricter contracts or tighter governance, are needed if trust is lacking.35 This is especially important because many stakeholders internally and externally influence a PPP.

First of all, stakeholders involve any individuals or organizations affected by or affecting the PPP project.43 Typical internal stakeholders involve the public sector, such as the central state, local government of a region, or various ministries, as well as any organization outside the public sector (private sector), such as private businesses, advisors, investors, banks and voluntary organizations.6,12,17 External stakeholders involve those with a legitimate interest in the project and/or are affected by it, i.e. the citizens, community organizations and non-governmental organizations (NGOs).17,43 It is important to note, that poor stakeholder management is one of the common reasons for PPPs to fail.9Due to the mutual involvement of all these stakeholders, good governance is needed. Good Governance generally involves good regulatory quality, bureaucratic efficiency and independence, while governments support the development with clear policies, strong commitment, as well as appropriate legal and regulative frameworks.25 Further governance principles include transparency, accountability, fair and honest processes, leadership, competitiveness and sustainability, which are quite demanding.17

As Bovaird (2004) argued, good governance in PPPs means in particular, that partnerships have to take responsibility for achieving improvements for the problems, which gave rise to the partnership; meaning, that the first objective of PPPs is mostly to improve the quality of life in areas of major significance to citizens and service users.17 Therefore, governance is also important to protect the public interest despite the delegation of authority to the private partner.9 The current design of PPPs does not give enough emphasis on the extent and nature of external stakeholders, resulting in inefficiencies.3 To ensure the progress and success of PPPs, public support by the civil society, trade unions and NGOs is crucial, as PPPs provide key public services for the citizens.2,5 Specifically, public opposition has been reported as one of the main reasons for failure of PPP projects.43 One the one hand, if the citizens are skeptical, distrusting or do not support a policy, condition, method or even a particular PPP project, criticism could arise; on the other hand, if a project is seen as being well delivered, public support improves.29 This is backed by a US study from Boyer and Slyke (2019) that examined factors that influence public attitudes and found out that familiarity with PPPs, trust in government and feelings toward the business sector influences attitudes toward them.44 Political support may also waver from the opposition.2 The following best practices address these difficulties and challenges.

First of all, it is important to note that the government has the leading role in the legitimacy of a PPP project, where accountability and public interest are crucial.3,8 Specifically, effective leadership to ensure goals and accountability, as well as strong political backing to sustain the project once legislations change, are crucial for the success of PPPs.31 In this regard it is important that governments keeps their governance responsibilities separated from commercial concerns.9 In addition, improving the procurement skills of the department staff involved in PPPs is an underlying practice to strengthen their expertise to improve the projects delivery and streamline the PPP implementation.34 For example, in Lima, Peru the building of an Expressway through a PPP resulted in failure due to a weak legal and institutional context, linked with a lack of transparency and accountability, which resulted in accusations of corruption.45

Hodge and Greve (2007) pointed out, that special organizational units may be a good way to ensure effective PPP governance. For example, some countries, such as Britain and the Netherlands, established centralized PPP units for a top-down approach that drives the adoption of PPPs across all the government’s levels; while other countries, such as Germany, Denmark and Sweden, organized themselves in a decentralized way for a rather bottom-up approach with more room for local decisions.9 A PPP unit could have the authority to evaluate and assess issues outside of the government’s typical competencies such as cost allocation, clauses, length of concessions and risk allocation.34Furthermore, tight governance may be needed to protect the public interest, but weaker governance is also needed to enable risk-taking and innovation.46 Governments should therefore avoid overregulation of private operators.25 Finding a balance in centralized coordination and governance is important to achieve flexibility and efficiency gains in PPP projects.12 Another important practice is to select the right private partner because both partners will work together for a very long time.3 Furthermore, PPP projects are difficult for a single construction company to execute, which means that a reliable, well-structured, financially strong and technically competent private partner is crucial.5,7 Abdel Aziz (2007) suggested a multi-stage process for contractor selection, including stages for interest, qualification, proposals, offers and the final negotiation.34 The whole selection process for partners must be fair and transparent to mitigate avoidable legal disputes that could impede the project’s progress.3 Governments may also assist in strengthening companies both financially and technically to build their capacity to be able to compete with international project companies.5

As an example of good governance, Biygautane et al. (2019) describe how Saudi Arabia developed an airport in Medina in 2010, despite many constraints.47 The public sector faced many deficits, such as a lack of understanding of the PPP concept, missing administrative mechanisms, weak ministerial communication, transparency issues, lack of skills and expertise, and the absence of a PPP law.47 The government contracted a consortium of international private firms through a BTO agreement for 23 years to build and operate the PPP project after a feasibility analysis and a recommended PPP model.47 In addition, the government took steps to overcome the institutional constraints by streamlining administrative procedures, ensuring transparency throughout the whole process, hiring experienced staff for a new PPP department, drafting a legal team for the agreement, and seeking international professional advisors.47The whole process was complemented by the involvement of different ministries and even a royal order for political support.47

To build strong relationships, trust and ultimately an effective PPP, the involvement and alignment among all stakeholders are essential.10,25 Specifically for stakeholder involvement, El-Gohary et al. (2006) developed a semantic model, which thoroughly captures the actors, concerns, processes, resources and strategies behind a PPP project.43 The model incorporates many essential steps and strategies toward creating a strong involvement program that will help in effective communication and stakeholder management.43 To foster relationships, governments can set up formal relationship standards and procedures to foster trust.8 They may even give assurances to the private partner about future revenue guarantees, as well as assurances to the public about quality and reasonable end user fees in this regard.2,5

For the relationship between the public and private sector, both parties should consult each other for any clarification on the projects’ delivery throughout the whole procurement process.5 These regular consultations especially help to clarify uncertainties. Furthermore, they create a foundation for true partnering between the two sectors.21 As for the public, mechanisms for a deeper level of acceptance and participation are needed.48 First of all, it is important to clear any doubts or rumors from the public concerning the delivery of PPP projects.5 Consistent and clear communication with all (internal and external) stakeholders is vital for success as it boosts trust, transparency, engagement and support for the cause.31 In addition, publicly made information and reports can improve transparency for all internal and external stakeholders.5 It is also crucial, that PPPs should consider the interests of the citizens and other stakeholders, as well as include all the stakeholders in the decision-making.3,17 This interactive engagement reflects citizens’ interest, includes them in the development and also improves public support.48 According to George et al. (2024), a good case example for involving all stakeholders is the Hyderabad Water Supply and Sewage Board project in India.22 The public leaders created forums involving interactions among the public sector members as well as consultation mechanisms with citizens to foster awareness and get useful input.22

2.3.2 Long-Term Contracting

A PPP involves a cooperation between the public and private partner for a whole lifecycle of an infrastructure asset, lasting at least 10 to 20 years, mostly bundled in a single ‘one-covering contract’.49 The typical contract lasts for 20 to 35 years6, but can stretch up to 99 years due to contractual payments.30 PPPs typically involve longer bidding and contracting periods than traditional procurement methods and due to uncertainties from long concession periods and the inherent incompleteness in every detail of the project, PPP contracts often need adjustments along the way.25 A striking fact is that PPP concessions are routinely renegotiated because the contracts last for several decades and thus incomplete contracts are to be expected.24 Failed renegotiations during the life cycle and adverse institutional conditions, such as contract enforcement or unrealistic demand expectations from the government, are some of the reasons for lower success of a PPP.6 To summarize, “PPP contracts are long-lasting and constantly changing” (p. 17)25, adding additional complexity to the already complicated activity of contracting, which aims to align opposing interests of different actors into an agreement packed with mutual commitment.49

As Martimort and Pouyet (2008) suggest, to better understand the optimal delegation of public services, it is important to consider the complex array of tasks involved in procuring a public service.50 Those tasks necessitate, first, the building of infrastructure and, second, the efficient operation of these assets. With PPPs the governments adopt a more minimalistic stance, selecting a private consortium responsible for designing the infrastructure’s quality attributes, constructing the assets and managing them as efficiently as possible.50 Typically, it involves the bundling of the tasks of design, building, finance, operation and maintaining, assigned to a consortium6; however, governments may also bundle several smaller or similar projects together, either to be jointly procured and tendered or to be managed by a single private sector partner.49 The consortium typically involves all the partners from the private sector organized into a special purpose vehicle (SPV) responsible for the tasks.2 This act of bundling should save operating costs10, contribute to the dispersion of transaction costs and create economies of scale49, but increases the projects complexity further and limits the participation of smaller private companies.6 The following best practices address contracting and bundling in PPPs.

Formal contracts are an important governance mechanism to provide guidance, clarify stakeholders’ responsibilities, effective risk allocation and give a legal framework for future PPPs.10 A good practice is to fit those contracts to specific technological, strategic and institutional settings.13 As Van Den Hurk & Verhoerst (2014) argued, standardization of contracts might be another solution to settle negotiations more quickly, lower transaction costs, foster competition by enlarging the field of potential bidders and render learning for future contracts.49 They discussed, that it can play an important role in PPP practice and generally be seen as a PPP-simplifying governance tool, but the benefits depend a lot on whether the public actor considers it as a guiding instrument or a control tool.49 However, standard contracts with rigid specifications may constrain private partner’s commitment10, could cause further harm in negotiations and flexibility due to the restrictive nature and have a negative impact on the local level of the infrastructure asset to be built.49 It is precisely due to the many uncertainties that a certain necessity for flexible agreements and contract renegotiations is important.25 Governments may then build on past experiences and fix many aspects in future contracts more easily.51 Thus, the challenge lies in balancing the opposite forces and using a formal or standardized contract in a complementary way or as a guideline.49

Another option is to design tendering procedures and contracts in such a way that ensures competition, transparency and accountability.13 In that aspect, Cui et al. (2018) suggest proactive measures to reduce (re-)negotiation costs, such as incorporating key contract clauses while keeping an incomplete contract.25 They emphasize flexible contract terms, dynamic contract supervision and an analysis of renegotiation triggers during the lifecycle of a PPP project before potential conflicts even appear.25 Including renegotiation clauses could be another solution, for when the environment changes, new information arises or errors are discovered.24 Early involvement of private partners in the process is also encouraged through competitive bidding and negotiation procedures.13 Jointly clarifying goals and metrics, such as values, rewards and outcomes, as well as establishing relational linkages early on may be a potential for better valuation and trust between partners.22 To make sure the other party abides by the contract, the possibility of applying sanctions provides steering options during the later implementation of the project.35

Another factor to consider is the bundling of tasks. By bundling, externalities can be better addressed and managed.50 A positive (or negative) externality refers to the case, where a building innovation reduces (or increases) costs at the management stage.6 With positive externalities, bundling is preferred and increases welfare; when the externalities are negative, unbundling reduces agency costs and is socially preferable.50 The question lies further, which tasks in PPPs should be bundled into a consortium or instead unbundled and undertaken by separate firms6, when the externalities are uncertain and other factors are present. Building on the previous research, Dolla and Laishram (2020) developed a theoretical framework specifically examining factors for bundling tasks on PPPs.52 They gave propositions on various phases in the PPP project, presented factors that influence bundling decisions and gave recommendations for (un-)bundling tasks.52

2.3.3 The Role of Risk-Sharing

Risk is a crucial element of PPPs, as it involves long contracting/concession periods and involves many participants in the partnership.7 PPP generally have more risks and a higher degree of risks than other procurement methods.18 As one of the main benefits of PPP, the allocation of risks has attracted significant interest from researchers.25 “A risk is seen as an uncertain possibility” (p. 303)18; or more precisely, a “probability that the actual outcome will deviate from the expected outcome” (p. 48).2 Risk-sharing allows both partners to transfer some of their risks, ensuring that neither side bears too many risks, which encourages them to work closely together.18 Researchers seem to agree that risk-sharing between both sectors is a major consideration for successfully integrating their strengths.9

First of all, it is important to identify the risks involved in a specific PPP project.25 There can be many kinds of risks to consider in PPPs.9,18 Wang (2018) classified risks generally into project-related, market-related, social and country risks.18 Project-related risks are the risks that occur due to the project’s uncertainty and complexity, covering areas like design, development, construction, finance and operation.18 Examples are design deficiencies, construction delays, poor quality, higher maintenance cost, lack of commitment, and inadequate distribution of responsibilities and authority.53 Major risks involve the creation of unbalanced partnerships due to the constant conflict of interest between the partners3 and high operation and maintenance risks due to depreciation over a long contracting period.6 Market-related risks are generated by the market, seen from a macroeconomic view, including inflation over the contract period, interest rate fluctuations, competition and market demand fluctuations.18,53 Social risks involve the public dimension and are in some way linked to market-related risks due to user demand.18 Examples are public opposition, demand fluctuations and illicit acts of third parties.53 Especially the public opposition is a major risk because PPPs often have greater visibility.18 Country risks are related to the country’s specific uncertainties, typically on the political and legal level.18 There are many examples such as an unstable government, corruption, law and regulatory changes, poor decision-making and poor governance.53 Political risks play a crucial role in PPPs as weak political support could influence public opinion, might dissuade private sector participants and further increase many other risks.2 Governance risks also appear to have increased with PPPs, like the desire of governments to proceed with hasty project construction for political purposes and the inadequate transparency of the projects.9

It is important to note that there is no universal list of all risks that apply to all PPPs, as their presence and degree depend on a variety of factors such as project type, sector, size, location and PPP type.7 Therefore, rigorous risk analysis and optimal risk allocation are fundamentally important for all stakeholders involved in a PPP.3 Risk allocation refers to which party assumes the risk in the end.27 It is precisely because there is a mix of risks from both sectors, that there are differences in which partner is better able to handle which type of risk.7,34 Furthermore, once the risks and their potential impacts are identified, strategies for risk mitigation are useful.2 Each risk should be assessed in terms of its effects on the project and the end users, and allocated to the partner, who is best able to manage the occurrences and for whom they are most affordable.2,27,34 The following best practices address the allocation of risk.

First of all, Governments should refrain from the idea of transferring all the risks to the private partner.5 Doing so may result in the private firm either avoiding any relational interactions and large upfront investments or alternatively charging very high risk-premiums.24,31 Risk allocation is influenced by a country’s governance environment.27 For weaker governments or weak environments, less risk should be transferred to the private partner due to higher political risks.6 In countries with good governance, the environment has matured and private investors have full confidence in the cooperation.27 Different regions thus need different risk allocation models.25 Besides the governance environment, the type of project affects the allocation of risks.18 For example, in prisons, users do not pay and the demand is imposed, thus the demand risk remains with the government and no revenue risks are involved; in leisure centers, user fees are needed, thus the demand risk is mostly shared and revenue risks lie entirely with the contractor.6 Typically, most political and legal risks should be assumed by the government, while most project-related and market-related risks are retained by the private sector, as well as other risks subjected to several considerations are shared between both.7,34

The effects of the risk allocation should also be assessed on the project and the ultimate users of the infrastructure.34 To determine and alleviate current risks, project owners should regularly communicate with all stakeholders involved, especially the funders, involved teams and local citizens, through regular consultations or project information disclosures to the public.27 Governments could design an effective risk allocation plan by engaging all stakeholders, consulting experts, as well as recording and learning from other PPP projects, which could mitigate future risks.27Following a suggestion by Roehrich et al. (2014) there is a need for standardization of risk assessment tools, appropriate risk pricing and improvement in transparency of risk types.10 Cui et al. (2018) also suggest improving risk assessment and allocation by systematically quantifying the risks based on factors such as the project type, implementation stage, location and other aspects.25 Proper risk transfer provides incentives, lowers costs and efficient provision of services.6

2.3.4 Financing Mechanisms

Financing is another key element in the provision of public infrastructure, as the challenge lies in finding the necessary resources for the PPP project.24 In particular, as the construction of public projects often ends up costing more than previous cost estimates6, requires larger financial flows9, and suffers from unreasonable capital structures39, a firm financing structure is essential to mitigate risks and the failure of a PPP project.7 The main project sponsors are domestic private equity investors and foreign investors, such as construction companies, operating companies and banks.27 The distribution of investment between the public and private sector to finance a PPP is a key factor as it determines the interest of both sectors, influences the contract design and arrangements, the process of contract (re-)negotiations and the organizational structure of the projects.4 During the project’s life-cycle, the sources of finance change depending on the phase.24 Especially the use of private finance is of importance due to the large infrastructure investments needed for a long time and the important role that infrastructure funds play.6 Private financing is usually associated with high upfront investments and lower costs in the operation and maintenance phase, in which the revenues over the life cycle pay off the debt24, often at a higher cost to the government than with public debt.21However, both public and private actors finance the project in some way, while the public partner pays periodically recurring fees later in the operational stage for the private sector’s early financing.49 Governments may use taxes from the users (or through the general public) to pay the contractor performance-based or agreed payments for the service provided.34 The payments to the private sector partner can also be directly made by the users of the facility through tolls and user fees.6,24 The following best practices describe methods to calculate financial resources needed and address financial strategies.

The public sector commonly uses the ‘public sector comparator’ in evaluating and selecting a PPP project, a tool to compare how much building an asset through public funding would cost with how much it would cost to build as a PPP.3 Often it is combined with the Value for money (VfM) analysis, which is the combination of costs, risks, time, budget, quality and more.18,21,34 However, VfM is not as important for public procurement, as the main goal of PPPs is not economic feasibility, but rather to procure a needed infrastructure, service or a social outcome.21 Further methods besides the VfM-analysis might be considered, such as quantification of risks, life cycle cost analysis, revenue modeling, financial analysis and determining various quantitative and strategic factors.34

Additional factors that play an important role in PPP financing need to be considered, including market needs, tariff structure, concession period, credibility of the project, financing sources and external events.7 For an appropriate capital structure, critical factors of the specific PPP projects need to be considered. Du et al. (2018) analyzed 15 cases for several critical factors that influence the capital structure of PPP projects, including benefit, cost, ability, risk, project condition, government support and external situation.39 Based on different combinations of these factors and depending on weaker or stronger variables, they developed strategic variations on capital structuring, in which the private sectors’ equity-to-debt ratio varies.39

Government measures can be taken to ensure an appropriate capital structure, such as setting a cap on revenues, enforcing specific mechanisms for setting toll rates, requiring a specific equity-debt ratio, limiting the rate of return, and limiting the concession period to the time in which all debts are repaid.34 To encourage the private sector to finance the project, governments may support the private partner in the form of a guaranteed minimum revenue for the services.7 In particular, to prevent unreasonably high profits from private partners on behalf of the taxpayers and users, benefit-sharing arrangements are a good practice to return profits over a specific threshold back to the public.13 For example, a parking lot built for a hospital in Scotland covered by an existing PFI contract resulted in the private firm profiteering from the hospital workers and the people in need of the service, as the private firm was fully in charge of the car parks.45 Clarity and consistency in the definition of financial indicators for sponsors and lenders can help to avoid misunderstandings and improve trust between the parties involved, especially among foreign participants in PPPs.42 With adequate financing, PPPs are not inherently more costly through private financing than public debt, as sophisticated financial engineering through adequate measures can reduce the higher cost of capital.24

2.3.5 Sustainability-Oriented PPP

Sustainability is gaining more and more significance in project delivery, as stakeholders require ethicality, environmental sustainability and economic efficiency throughout the whole project’s life cycle.26 Modern views of sustainability generally cite three interrelated dimensions – economic, ecological and social sustainability, with the social dimension being the most commonly researched in PPPs.14,26,37 To measure the dimensions of sustainability in PPPs, there are many indicators, such as economic prosperity, cost efficiency, internal rate of return and life-cycle costs (economic), energy efficiency, pollution, environmental protection and impact on geographic conditions (ecological), contribution to quality of life, provision of quality services, job creation and promotion of health & sanitation (social).4Recent research has explored the creation and maintenance of sustainability-oriented PPPs, in which the topics of sustainability, governance and stakeholders have become more important.23,37 In terms of stakeholders, the creation of social value appears to be of high importance in the literature and practice.54

Most PPP arrangements are two-way affairs between the government and a private business without explicitly reflecting citizens’ perspectives sufficiently.9,51 The recent approach by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) involves ‘people-first PPP‘ and is designed to overcome some of the weaknesses of the traditional PPP model, as it focuses on delivering value for the people.41 In this context, ‘social value creation‘ has emerged as a crucial and increasingly dominant sustainability objective for PPP projects.12 Social Value refers to the benefit that a society gains as a whole from a PPP infrastructure project25 and is considered a key sustainability category, which includes indicators like equality, human rights and public meeting.55 It can be created when the partnership generates some kind of positive societal outcome, beyond what one organization could create.54 Involving the public in some ways can help to ensure that the PPP project better reflects societal needs.

However, PPPs’ impact on the public interest may be a concern, due to the private partner’s prioritization of profits rather than on the public interest.3,4 If for example, the public sector contribution is minimal, environmental and social considerations of an infrastructure may not be considered in favor of private profit priorities in the economic feasibility of a project.4 Therefore, citizens may be excluded from sustainability considerations if governance measures from the public partner are weak.14 As of Reynaers (2014), there is still not enough empirical evidence on whether social values can be threatened, safeguarded, or even strengthened through PPPs, as it mostly depends on the project phase and specific values in question.32

As one of the main objectives of the SDGs, building reliable, sustainable and resilient infrastructure is crucial for achieving sustainable development in many countries.25 Over the past decades, PPPs have already been used for sustainable development across some areas of public infrastructure and services.27 An example is the London Olympics 2012, where the buildings and equipment were designed and intended to be reused, repurposed or dismantled.56 More recently, they have been recognized by the UN as a potential tool to achieve the 17 SDGs.25,37 Through an analysis of empirical studies about sustainable development in PPPs, Pinz et al. (2017) indicated that PPPs have been used in various fields that appear critical for sustainable development and thus are linked to the SDGs presented in Agenda 2030.14 These areas in which PPPs are implemented – such as infrastructure and transportation (SDG-9), school buildings (SDG-4), health care (SDG-3), fire/police departments and prisons (SDG-16), water (SDG-6), energy supply (SDG-7) and urban development (SDG-11) – have clear impacts on the social and ecological environment and may have the potential to support sustainable development.14 Acknowledging the importance of collaboration, ‘partnerships for the goals’ (SDG-17) encourages global multi-stakeholder partnerships (target 17.16) and effective public-private partnerships (target 17.17) to tackle complex societal problems with coordinated efforts, goal alignment and resource mobilization.22,38,57 The scope of the SDGs makes it difficult for a single entity to achieve them, so partnerships are needed to share knowledge, expertise, technology and financial resources.38

Despite PPPs’ potential for sustainable development, there are several underlying issues. Pinz et al. (2017) analysis also revealed that PPP currently “simply fails to contribute to the accomplishment of sustainability-related objectives” (p. 10)14 and “little empirical evidence confirms whether PPPs are appropriate instruments for accomplishing sustainability-related objectives” (p. 16).14 Sergi et al. (2019) performed a research on 14 developed and 14 developing countries to measure PPPs as a mechanism for financing sustainable development.58 They found that there currently remains low effectiveness of financing sustainable development and PPPs are insufficiently used for it, partly because most PPPs focus on infrastructure.58 Furthermore, a problematic emphasis on the measurability within PPP projects leads to a weak conceptualization of sustainability and a limited amount of evidence.38,55 Specifically on ecological sustainability, Shahbaz et al. (2020) analyzed carbon emissions in PPP projects in China and found that PPPs have a positive effect on carbon emissions (i.e. affect environmental quality by increasing CO2 emissions), which is contrary to the typical improvements on environmental quality by technological innovations.59 Theoretically, the successful implementation of PPPs should improve sustainable development in various fields of infrastructure.

Several previously identified best practices on the key elements appear to be coherent with sustainability considerations. As Pinz et al. (2017) analysis also showed, that risk allocation, responsibilities throughout the whole partnership process, good governance and an adequate capital structure are important for successful PPP management and crucial for the accomplishment of sustainability-related objectives.14 Further examples of coherent objectives that have been described in sustainability-focused literature include strong political commitment, involvement of further stakeholders, a more flexible governance structure, contract regulations, building trust, shared understanding, goal alignment and clear communication.12,13,51,55 All of them influence the successful implementation of PPPs in some way and thus also promote sustainable opportunities. Further best practices focus on sustainability considerations applied throughout the whole life-cycle of PPP projects.

To turn sustainability considerations into action, appropriate measuring of sustainability is important, in which sustainability indicators play a crucial role in setting proper targets, monitoring progress, and determining appropriate performance.2,55 In this regard, Hueskes et al. (2017) developed a sustainability framework with 54 key indicators to assess sustainability from a broader perspective than the traditional focus on social, ecological and economic aspects.55They defined main categories such as ‘environment’, ‘liveability’, ‘health and comfort’, ‘social equity’ and ‘community and participation’ at the first level, broke these down in more detail at a second level and then further into more specific examples of indicators at the third level, providing a basis for a proper assessment of possible sustainability objectives.55 Both partners need to continuously assess possible sustainability objectives and seek improved ways of increasing the sustainability of policies and activities.17

Sustainability needs to be integrated into ordinary project routines and could be added to existing tools and methods.26As an example for a method, Berrone et al. (2019) introduced the ‘EASIER evaluation model’, which considers not only the economic impact of a PPP (i.e. the typical VfM analysis and feasibility of a PPP project), but also its impact on society and the environment.38 The evaluation model consists of 53 questions covering six dimensions – Engagement of Stakeholders, Access to all population, Scalability and replicability for a broader area, Inclusiveness of minorities, Economic Impact and Resilience of infrastructure to preserve the environment – which allows for a comprehensive assessment of the project’s sustainability and the alignment with the SDGs from an early stage.38 Furthermore, the SDGs could be generally used as a framework to set important targets to trigger changes in projects’ early selection and design.16 For example, SDG-4, which promotes quality education, can be targeted by conducting the training of local staff and other related stakeholders, as well as ensuring know-how transmission, or SDG-16, which calls for strong institutions and inclusive societies, can be targeted by making the project’s information freely available online.38,57According to Cheng et al. (2021), a recent case of a PPP project that actively implements the SDGs is a commuter-rail system in Taizhou, China, which considers the participation of all stakeholders and all people in the implementation.60The goals are implemented as much as possible according to the Agenda 2030; with some goals that are difficult to implement, while other closely related goals may be implemented according to the project’s characteristics.60

Furthermore, the selected PPP contract types provide different incentive structures that are likely to have an impact on sustainability goals and outcomes, in which some provide incentives for a full life-cycle or integrate project phases.55 A good step in reducing the failure rate of PPP projects might be to choose a suitable PPP type. The selection should be based on the key internal factors of the specific project (i.e. potential risks, planned contract design, capital structure and transfer of responsibility), and the internal and external conditions of the country.42 Each PPP type offers different structures and incentives, so aligning all factors with the appropriate type will ensure a better fit and long-term sustainability.

Governments may use governance instruments and incentives to stimulate sustainability.55 Projects that are unprofitable but may have an important impact on sustainability could be combined with more profitable activities, such as land and real estate development, where the added value co-finances the unprofitable parts and reduces ‘cherry picking’ profitable activities.13 Furthermore, governments may create an incentive system that rewards specifically government employees for sustainability performance, which ensures a stronger commitment to sustainability goals in the public sector.13 The private sector must be aligned with the other stakeholders by rewarding them for pre-agreed performance indicators, as well as incentivized in some way to find cost-effective solutions to sustainable development challenges.16 As Hueskes et al. (2017) argued, just mentioning sustainability aspects in the bidding process does not imply that the private partner will act upon those demands, making the formulation and weighting in the award criteria important to give them higher incentive value.55 Two options would be to (1) set a minimum score threshold for sustainability criteria to ensure the integration of sustainability considerations in the biddings, and (2) set a maximum or fixed price in the bidding process to ensure that competition focuses on better quality rather than the lowest price.55

To create social values, relational coordination, mutual knowledge and goal alignment are vital.54 This requires genuine partnerships between both partners, as well as involving all stakeholders. Stakeholder involvement is a dimension of sustainability by itself that can address the citizens and users into PPP development.55 It is important to note, that it requires to involve all individuals to ensure access to services and infrastructure of social interest for all citizens without any discrimination, particularly for the most vulnerable, the poorest and minorities.38 The public sector should therefore set and monitor standards for safety, effectiveness and quality, and ultimately ensure that citizens have adequate access to the infrastructure.3 Furthermore, the involvement should be balanced throughout the whole life cycle of the project.38

A best practice example for sustainability integration can be presented by Spraul and Thaler (2020) through a swimming pool PPP project in Germany, which addresses a focus on economic, social and ecological sustainability.51In 2006 the public sector, a municipality, planned to build a new public swimming pool, invited companies throughout Europe that could meet the needs and lastly awarded a German-based, but global operating firm the contract after negotiations.51 Building on experiences from other municipalities, the public partner implemented as many aspects in the contract as possible and taking into account sustainability considerations such as noise level, water temperature and quality.51 For economic sustainability, the PPP reduces public expenses, offers a new tourist attraction, creates new jobs and ultimately increases the regional value creation.51 Ecological sustainability was achieved by a life-cycle approach including energy and water consumption, heating through solar energy, a fit into the landscape and managing traffic through shuttle services and location.51 As for social sustainability, the PPP engaged several stakeholders through round table discussions, including citizens, users, employees, schools, sports clubs and local businesses, as well as regards for social acceptability, affordable fees, job security and benefits sharing.51 This example shows how sustainability can be integrated into the whole life-cycle, as it includes several sustainability considerations for a specific PPP project and learns from prior experiences of similar projects.

2.4 Measuring Success

Vastly different success measures exist across the discipline, the jurisdictions, researchers and those professionals employed in the PPP industry, as for example, success may involve to ‘get things done’, to ‘properly account for things’, to do it ‘on-time and on-budget’, to do things at ‘maximum efficiency’, to ‘govern well’ and more.20 The differing goals of the public and private partners highlight the necessity of assessing at a microeconomic level whether PPPs are a success or failure3, but it is no easy task to evaluate if they are successful or not, because many factors are coherent and interdependent.

“The question of ‘success‘ (or of ‘high performance‘) cannot be resolved without asking ‘success for whom?’” (p. 67).29Many actors are involved in PPPs and success may therefore be seen quite differently by each actor and the groups involved in the public infrastructure.18,29 The narrow view of success looks only at the political and business dimension, focusing on the particular outcomes and targets set in the agreement, such as the return on investment or economic feasibility.18,29 It is important to note, that political success in their concept is independent of business success; meaning that PPP projects may succeed (or fail) in political terms regardless of whether they fail (or succeed) in business terms29, for example when the public demand is strong, but the project ends in a financial loss.

The broader view takes into account wider benefits for the stakeholders and features the VfM analysis.18 A novel feature of VfM is, that it also includes some of the risks associated with the project.3 As mentioned by Cui et al. (2018), economic feasibility and VfM are mainly the key methods in scoping out and selecting a PPP project.25 However, they argued, that the VfM-analysis alone is not enough to reflect success and the accurate assessment of economic and social values of PPPs, as it does not consider public attitudes and other stakeholders’ expectations.25 When evaluating a PPP, social and environmental impacts, as well as intergenerational effects for future generations, should be considered, due to the long lifecycle of such projects, the long-term financial impacts on the local population and sustainability considerations.25 For example, Mladenovic et al. (2013) identify for the primary stakeholder groups three key performance indicators for stakeholder satisfaction, in which the public sector focuses on effectiveness and VfM, the private sector prioritizes profitability and the users seek a high level of service.61 They concluded that an evaluation of the different objectives from the standpoint of each stakeholder and a weighted combination of them might be able to describe whether a PPP is successful or a failure.61 An evaluation of whether PPP can improve at least one of the social, environmental and economic dimensions of sustainability could also be considered to incorporate sustainability considerations.14

The success of a PPP is never guaranteed, as achieving any of these goals is not always certain and they might even fundamentally conflict; ultimately coming down to ‘who gets what done and for whom’.20 To conclude, a PPP should not only be evaluated from a technical point of view but rather from an overall process perspective.18

2.5 Summary and Key Takeaways

2.5.1 Summary

This study provides a comprehensive review of the academic discourse on PPPs, in particular on the different insights, views and aspects. By analyzing the existing literature from various disciplines, this study covers many different elements that together constitute PPPs and addresses the current debates, challenges and best practices associated with them. It also explores recent advancements in structuring and managing a successful and sustainable PPP, as well as giving insights into the complexity and adaptability of PPPs. As many literatures have a central research focus on specific thematic elements, they collectively contribute to a better understanding of the structure of PPPs.

The focus lies on the detailed definition of PPP, the differentiation from other public procurement methods, an in-depth conceptualization of the key elements that constitute a PPP, the integration of sustainability considerations, and how to measure a successful PPP. While there is no clear standard definition for PPPs, they are broadly described as ‘long-term collaborative relationships between the government and private actors’, sometimes with additional elements that vary across disciplines and institutions. Many types and forms are classified under the ‘umbrella-term’ PPP that are shaped by different sectors, settings and views. The review identified five key elements for PPPs – governance and stakeholder alignment, long-term contracting, risk-sharing, financing and sustainability – each examined for its role, associated challenges and best practices underscored by some case examples. Governance is the central aspect of a PPP, as the public sector manages the long-term contract, the relationship between both partners and the stakeholders. Many types of risks are to be considered and allocated to the partner who is better able to handle them. In regards to financing, solid strategies and a firm capital structure are needed. Sustainability is of great interest to theory and practice, and a key section of the study, particularly to the three dimensions of sustainability, social value creation and the SDGs. The key elements and most best practices are interconnected in some way, as they all contribute to the success and also the sustainability of a PPP.

2.5.2 Limitations and Criticism

A major limitation of the research on PPPs is the large amount of diverse literature that can vary widely in terms of scope, type, definition, region, sector, factors, subtopics and much more. This is reinforced by the vast array of activities in which PPPs are used, the ever-changing economic conditions and the frequent policy changes around the world. This diversity poses a major challenge in providing a consistent and summarizing overview of the topic as a whole. This also gives rise to some parts being rather short-coming, which is also a limitation in itself. Due to these reasons, picking out specific studies and literature may additionally be subconsciously influenced by potential biases, such as cognitive, observer and researcher bias, which cannot be entirely reduced.

Moreover, most studies take on a public sector perspective, in which the private sector perspective is addressed to a limited extent, which constrains a comprehensive analysis equally on both partners and their mutual relationship. The availability of data for case studies is a further challenge as, on the one hand, there is some bias towards extreme examples and, on the other hand, details of PPP contracts are very confidential and need to be looked at over a very long period of time (20 – 30 years). Research tends to look at politically extreme cases (negative high-profile PPPs or very successful PPPs), which may not reflect the general global trend. Conclusions taken from these case studies might be inspiring, but their generalizability remains limited.27,51,55 Furthermore, empirical and statistical research is currently limited, due to the number of incomplete PPP projects.10,37 Most PPP projects are still ongoing, with many being in the operational phase.35 The measurability of PPPs also remains problematic and as sustainability is a topic that is not at the core of PPP research, the conceptualization of sustainability-related objectives remains difficult.14,55All this may affect the reliability of the current data.

2.5.3 Future Research Agenda

To address the limitations and criticism on the topic, future research could focus on synthesizing the many differences, especially in the political, economic, cultural and sectoral environments, and possibly drawing conclusions on how to deal with PPPs in specific situations. In particular, possible causes for the failure of PPPs in different sectors and countries could be examined in more detail10, preferably not through extreme case examples. Examining the role of the private sector in delivering public goods and services12 and looking at PPPs from the private sectors’ perspective could be additional opportunities for a better understanding. Similarities, differences, and particularities may also be extracted from these cases for a better understanding.32 In addition, as mentioned before, success is currently measured differently, future research may develop a framework taking into account all aspects of a project, which could be used for a better understanding of PPPs and also as a baseline for PPP measurability.

Furthermore, sustainability is playing an increasingly important role in the project delivery26, which is why research should ensure the measurability of PPPs and thus also sustainability, taking place over the entire life cycle of the project. Many studies focus on the social dimension of sustainability37 and seem to take in some parts of sustainability considerations in specific project stages. As PPPs are recognized as a tool for sustainable development15, future studies may take into account all dimensions of sustainability over the whole life-cycle of PPP projects.

3 Practical Implications

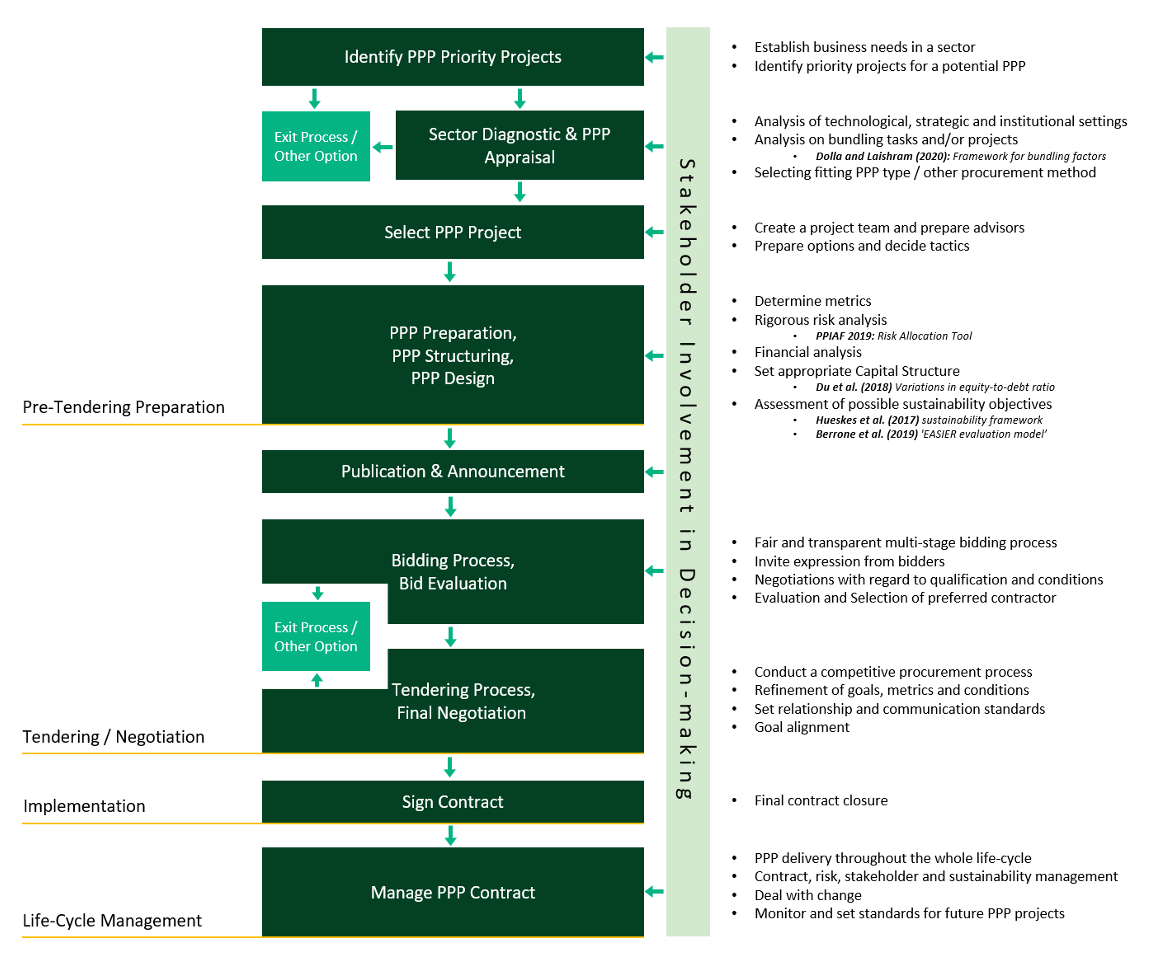

Establishing a successful PPP requires many considerations and multiple steps from both partners, in which a PPP process framework might provide guidance on how to manage a them over the whole life-cycle. The process framework outlines essential steps that both, the public and private sectors, should consider when planning and implementing a PPP project. It builds on the prior theoretical insights, especially the key elements and the practical best practices, and combines them with recent tools, guidelines and principles from (inter-)governmental organizations useable for practice. The drivers and barriers that follow illustrate the factors that encourage and discourage governments and private companies from establishing PPPs.

3.1 PPP Process Framework

The process of developing a proper PPP is complex, as each government may set different processes for establishing and implementing PPP projects. Standardization of the process helps to ensure that PPPs are properly developed, coordinated and aligned with the government’s objectives.16 The ‘PPP process framework’ shown in figure 3 involves four main steps incorporating a mix of different PPP processes made through different (inter-)governmental organizations, such as Asian Development Bank (2008), World Bank (2017) and UNECE (2022a), combined with some insights from the prior conceptualization, especially with frameworks proposed by the theory. The framework covers the public sector perspective, as the government is fully responsible for the entire process until the contract has been finalized.16 This is accompanied by involving all stakeholders affected by or affecting the PPP project throughout the whole life-cycle of the PPP project to develop an enabling environment.62

Figure 3: PPP Process Framework, own illustration, based on Asian Development Bank (2008); Kwak et al. (2009); The World Bank (2017)7,16,62

The first step of the process typically starts with identifying the business and service needs, especially which sectors are in need for critical public services and infrastructures. Potential projects are analyzed to set priorities for establishing a suitable PPP project. Once the outline is made, the sector and project are appraised to determine feasibility, which can be tested across several dimensions such as technical, legal, environmental and social feasibility.16 This includes analyzing factors such as technical issues and complexity, laws and regulations, institutional structures, governments’ capacity, sectoral constraints, market situation, economic situation, financial situation, bundling of tasks/projects, and much more.16,21,62 This appraisal also involves the examination of a fitting PPP type and alternatives, such as refurbishment of existing infrastructure or other public procurement methods. As each PPP option varies in responsibility and risk, the characteristics are compared against the objective and potential strengths and weaknesses are worked through.62 A decision is made on whether to approve the PPP project or seek other strategies.16 If the PPP project is selected, a project team, sometimes also a PPP Unit, shall be established to develop options and tactics.63Their task is to build a solid PPP structure and design for the tendering process to prevent avoidable conflicts and disputes.63 This preparation may include defining criteria and metrics such as responsibilities, incentives, sanctions, financing, risks, performance requirements and sustainable requirements (Sustainability dimensions, Social Value, SDGs).63 In particular, a rigorous risk and financial analysis are required for the successful implementation of PPPs. In this context, the Global Infrastructure Hub (GI Hub) has developed a guidance tool in 2019 for risk analysis to properly allocate risks between public and private partners in different project types and sectors.64 It presents risk allocation matrices across 18 different project types in sectors such as energy, social transport and water, with detailed project risks, discussions of risk allocation and possible mitigation measures.64 The financial analysis involves the determination of cost factors, using different analysis methods such as ‘public sector comparator’ VfM-analysis and life-cycle cost analysis, and setting a proper capital structure based on equity-to-debt ratio.