Author: Wiebke Johanna Hell, May, 2025

1 Introduction

Consciousness for sustainability has become a necessity in the 21st century. Economy, society and ecosystems globally are facing existential threats by the accelerating impacts of climate change, biodiversity loss, depletion of natural resources and growing social injustice amongst others. The concept of sustainability is broadly understood within the Brundtland report´s definition as the development that meets the needs of current generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs1. This definition emphasizes the importance of balancing environmental protection with economic growth and social wellbeing. To cope with the prevailing as well as prospective sustainability challenges, previous behavioral patterns must not be maintained and incremental changes will not be sufficient to meet global sustainability targets, such as the Paris Agreement, the United Nations Sustainability Development Goals (SDGs) and the European Green Deal, hence fundamental changes in economic structures, consumption and governance systems are needed2,3. This means there is a need to transition toward sustainability within socio-technical systems, many of which have traditionally contributed significantly to the environmental and social damage4. Shifting whole systems towards sustainability is a highly complex and multifaceted challenge that involves overcoming institutional inertia, technological lock-ins and deeply ingrained behavioral patterns5. This challenge is taken on by the field of Sustainability Transitions (ST) research, which seeks to understand and facilitate long-term, systemic transformations of socio-technical systems to address environmental, economic, and societal challenges6,7.

Over the past two decades, the field has developed significantly and created several influential theories and frameworks that intend to guide the study and management of transitions. This thesis aspires to contribute to this field by providing a comprehensive literature review with a focus on the role of businesses in ST and how they can practically implement sustainability transition strategies. Frameworks that have fundamentally influenced the field and the conduction of this review are The Multilevel Perspective, Transition Management, Technological Innovation Systems and Strategic Niche Management. The Multi-Level Perspective (MLP), developed by Geels (2002, 2010), invented the conceptualization of transitions into interactions between the three levels of niches, regimes and landscapes. Transition Management (TM), proposed by Rotmans, Kemp and van Asselt (2001) and further refined by Loorbach (2006, 2010), provides a governance approach for steering transitions3,7,8. How new technologies and therefore important innovations emerge and scale within socio-technical systems is analyzed by Technological Innovation Systems (TIS), which was developed in studies by Carlsson & Stankiewicz (1991) and Bergek et al. (2008)9,10. Kemp, Schot and Hoogma (1998) and Schot and Geels (2008) examined how sustainable innovations develop within small, protected niches before challenging dominant regimes and formulated the framework Strategic Niche Management (SNM)11,12.

Research on ST is in constant movement since it directly correlates with the ever-changing challenges of guiding socio-technical systems. It is a dynamic, complex field, continuing to adapt to the fluidity of change and therefore susceptible to additive findings.

This thesis´ research aligns with the existing literature and aims to summarize the extremely broad knowledge base in a more compact way to be able to generally disseminate an actual understanding of sustainability transitions and their management. While much of the existing work has laid focus on policy and governance, this research aims to fill a gap by addressing implementation strategies for businesses, providing businesses with actionable insights on how to implement sustainability transitions successfully.

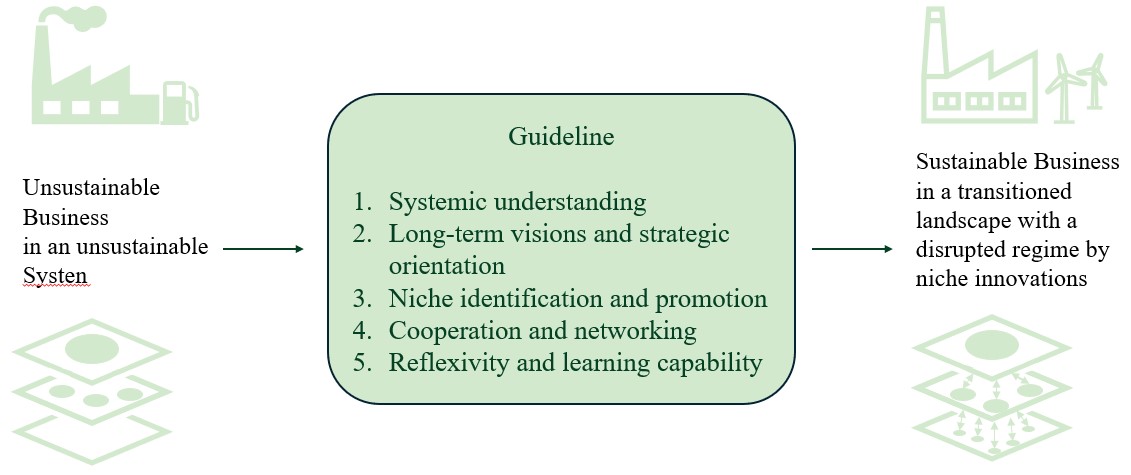

The thesis is further motivated by the chance of being a part of the initiative “The Sustainability Management Wiki – a public source for anyone seeking to improve the ecological and social performance of organizations” by the Management Research Group at the University of Oldenburg (Germany), to offer guiding knowledge on how to improve a sustainable performance of organizations. The topic “Sustainability Transitions and Management” is particularly complementary to this cause since it evaluates the possibilities and necessities of transitioning from unsustainable to sustainable businesses. The research question of this thesis is:

What is the current state of research on Sustainability Transitions and their management approaches and what are the implications for businesses?

2 Literature Review

The following literature review is divided into 6 chapters. The first chapter is 3.1, Key Terminology, where frequently used terminology within this thesis will be defined briefly and put into context. In 3.2, Historical Background, the origin and development of sustainability transitions and their management concepts will be unraveled up until the current state of research. In 3.3, Sustainability Transitions, ST will be evaluated in depth with regards to steps and processes during a sustainable transition. The Core Frameworks for Management of Sustainability Transitions, the big four core frameworks will be evaluated and supplemented by additional pertinent literature findings in chapter 3.4. Chapter 3.5, The role of businesses in Sustainability Transitions, puts ST and businesses in relation and in 3.6, Limitations and future research directions, limitations of the previously discussed ST and their management frameworks will be listed and resulting recommendations for policies will be named. This chapter provides an answer to the first part of the research question about the current state of research on Sustainability Transitions and their management approaches.

2.1 Key Terminology

To provide a thoroughly educating reading experience, terminology that simplifies understanding the literature will be shortly presented in this chapter, ascending from simpler basic terms like `transition` to more complex terminology.

The explanation in dictionaries such as the Oxford English Dictionary suggest that the term transition stems from the Latin word transitus which is translated by “passing over, crossing, changing” and refers to a gradual, long-term process of change15. In this context, it is the type of change in which a system undergoes a fundamental transition in its structure, including functions and practices is to be considered. These transitions are typically non-linear and occur over extended periods, often spanning several decades. The terms “transition” and “transformation” are often used interchangeably in scientific discourse, both signaling the necessity for largescale systemic change. While they share similarities, they offer distinct analytical perspectives where transformations are often considered more disruptive and encompassing, whereas transitions are structured processes that can be influenced through governance strategies16. Given the complexity of these concepts, a deeper exploration would go beyond the scope of this thesis and will not be conducted. For understanding and the sake of the reader, transitions and transformations will further be used almost interchangeably with the small distinction that transitions are understood as the process of change between state a and b, and transformations are used as a change that has already happened between state a to b.

Sustainability transitions are understood differently than regular transitions, which can occur for various technological, political, or economic reasons and occur naturally in societal and technological evolution. Sustainability transitions are purpose driven and explicitly oriented toward achieving long-term sustainability in environment as well as society, guiding systemic changes toward ecological resilience and social well-being4,17. According to Markard et al.

(2012), sustainability transitions refer to “long-term, multi-dimensional and fundamental transformation processes through which established socio-technical systems shift to more sustainable modes of production and consumption” (p. 956)17. The field of ST research seeks to understand and facilitate these transformations of socio-technical systems to address the existing and arising environmental, economic, and societal challenges6,7.

Socio-technical systems are complex systems that recognize the interconnected network of technology, people, cultural practices, markets and organizational structures and emphasize their interconnectedness. Literature on socio-technical systems stresses that innovation can emerge from the interactions between the systems elements, for example between new technologies, government policies, infrastructure and consumer behavior, which all operate at different levels, influencing and interacting with each other until they eventually reach joint optimization18.

Governance strategies through which ST can be influenced have emerged from the field of ST research as analytical and governance frameworks. These management approaches guide the shift from unsustainable socio-technical systems toward sustainable alternatives and have been prepared by cooperating scientists and experts of diverse sectors6,7. Their literature states that ST involve long-term, multi-actor processes which require innovative interventions of policy, stakeholder engagement and adaptive strategies7,17. The diversity of sectors brings a need for versatile approaches to achieve large- scale and lasting change, whether it is the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy, the restructuring of urban infrastructures to promote circular economies, or the transformation of agricultural systems to support regenerative practices4. Over the course of the literature review, four frameworks have repeatedly been cited and referred to as core frameworks for ST management: Transition Management (TM), the MultiLevel-Perspective (MLP), Strategic Niche Management (SNM) and the Technological Innovation System (TIS) framework, which, together, offer complementary tools for managing sustainability transitions, addressing governance (TM), systemic interactions (MLP), niche innovation (SNM), and technological evolution (TIS). The frameworks are presented in depth within this thesis in chapter 3.4.

Another useful term is “circular economy”, which is name-giving to one of the complementary frameworks in chapter 3.4.5 and can ultimately also be seen as a possible goal of a sustainability transition. It describes the alternative to the current linear economy model, where resources are not used in a linear way where they end in a landfill, which has evidently caused environmental and social repercussions, but where resources are used in a circular process, so when they have reached their final form, they are broken back down and built up again (recycled, reused). This generally reduces the resources used and offers a sustainable economy model which addresses the numerous challenges by minimizing polluting waste and offering options for new products with the recycled or re-used materials as well as fostering healthier communities19.

2.2 Historical Background

The historic background of ST and TM is closely linked with the evolution of environment and sustainability movements as well as the growing knowledge about the necessity of systemic changes. Their roots reach back into the midst of the 20th century with a systemic embedding in the nineties.

Awareness and understanding of sustainability were induced by environmental movements following first warning signals in the 1950s to 1970s when publications like Rachel Carson´s

“Silent Spring” (1962) captured attention about environmental problems like pesticide pollution20. The reoccurring crisis concerning oil leakages in the seventies made the dependence on fossil resources and the environmental aftereffects clear. In 1972 “The Limits to Growth” was published within the Club of Romes’ “Project on the Predicament of Mankind” and pointed to the finite natural resources and argues that unlimited economic growth without consideration of ecological limits was unsustainable. The Club of Rome was formed in 1968 and is an informal organization that consists of experts from different disciplines, e.g. scientists, educators, economists, humanists, industrialists and national and international civil servants. According to the Club, its purposes are:

“(…) to foster understanding of the varied but interdependent components – economic, political, natural and social – that make up the global system in which we all live; to bring that new understanding to the attention of policy-makers and the public worldwide; and in this way to promote new policy initiatives and action.”(p. 9)21

– which is the essence of what sustainability transitions and their management propose: profound cooperation of educated experts from different fields to solve problems that involve cross-sectoral interactions and to reach common sustainability goals.

One cooperation where representatives from 114 governments came together was the first United Nations (UN) environmental conference in 1972, which marked the beginning of an international debate about environment and development21. The World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) found that critical global environmental problems are primarily the result of severe poverty in the south and unsustainable consumption and production patterns in the north. It therefore called for a strategy that brings development and the environment together and introduced the concept of sustainable development in the Brundtland report, published in 1987, which defined a development as sustainable if it “meets the needs of the present, without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”(p. 43)1. At the same time as environmental problems were increasingly realized as systemic and global challenges, academic research started to address the dynamics of long-term social transitions.

Following that, the concept of socio-technical transitions emerged in the nineties, which describes how technological, institutional and social changes intertwine to establish sustainable innovations22. These ideas later developed into today´s established frameworks for sustainability transitions. The research on transitions originated in the Netherlands, driven by the works of now renowned scientists like Johan Schot, Frank Geels and Jan Rotmans, who investigated long-term societal and technological changes such as the transition from horse carriages to automobiles.

Furthermore, the Multi-Level-Perspective (MLP) approach was developed to understand transition processes as interaction of three levels: the niche, the regime and the landscape. Simultaneously, Strategic Niche Management (SNM) emerged, which emphasizes the role of experimentation and learning in protected environments to nurture sustainable innovations3,12,23. Research intensified before Transition Management (TM) was formalized as a governance approach designed to steer sustainability transitions by integrating principles of complexity science and participatory governance, focusing on long-term visioning, adaptive strategies and stakeholder collaboration7,24. The previously named approaches are core concepts in transition management and will be further analysed in chapter 3.4. In the early 2000s, TM was implemented in the national politics of the Netherlands, especially to support a sustainable energy industry and water management. The idea was for the policies to be able to support transitions to sustainable systems through targeted control of long-term innovations8.

Between the 2000s and the 2010s, scientific consolidation took place when TM was further developed as a theory, especially by institutions like the Dutch Research Institute for Transitions (DRIFT). The contemporary developments in ST emphasize their integration into global and national policy frameworks. When the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were passed in 2015 by the United Nations, they provided a global roadmap for aligning transitions with sustainability objectives. They focus on the interconnected nature of environmental, social and economic goals, reinforcing the need for systemic approaches like TM. Their connection with TM moved into focus when businesses started implementing transition management approaches to design their sustainability strategies that came with the SDG´s Agenda 30 to reach significant sustainability goals by the year 20302.

Since the beginning of concerns, the climate crisis and loss of biodiversity gained more global coverage, especially through the media in the last decade, which accelerated the debate about Sustainability Transitions. The current state of research on ST and their management continues to expand, moving towards greater complexity, inclusivity and interdisciplinarity. The MLP remains one of the most cited frameworks, yet contemporary studies have refined its applicability, incorporating geographical and institutional variations to its analysis4.

Another growing area of interest is research concerning social justice, which has gained policy traction within the European Green Deal and Just Transition Fund, aiming to ensure that ST are socially equitable and inclusive, ultimately integrating the concept of Just Transitions in the transition discussion25-27. Additionally, factors that critics previously found underexplored gained recognition, e.g. the role of power dynamics and political processes in shaping transitions, as well as research focus beyond the Global North, acknowledging that the majority of existing literature has been Eurocentric28. Further studies explore issues such as resource dependency, energy peripheries and developmental inequalities in context with sustainability transition theories in the Global South29,30. The necessity of collaboration between governments, businesses and civil society has also gained focus in recent studies, claiming that policy mixes including regulatory, market-based and voluntary instruments are needed to steer transitions effectively31. The role of businesses in general has received substantial attention, with studies examining how firms adapt to and shape transition dynamics, which will be further explored in chapter 3.5. Finally, the field has embraced methodological advancements like mixed method approaches, which combine qualitative and quantitative analyses. These provide a more comprehensive understanding of the processes of transitions. Computational advancements among other innovative approaches for modeling and analyzing further enriched insights into complex system behaviors32,33.

From the early environmental advocacy of individuals to the institutionalization of transition frameworks in policy and practice, critical insights have been provided that shape the research on ST and their management to this day. The management approaches, which evolved from academic concepts to practicable frameworks, find acceptance and application in politics, economies and civil communities globally.

2.3 Sustainability Transitions (ST)

The topic surrounding sustainability transitions is far-reaching, interdisciplinary and very complex. In order to provide as compact an overview as possible with the given resources, the chapter was divided into definitions and scope, key characteristics and the process of ST.

2.3.1 Definitions and Scope of ST

Building on the description in 3.1 Key Terminology, Sustainability Transitions are changes of complex socio-technical systems towards more sustainable modes of production and consumption. These transitions involve several actors over several years during which new products, services, business models and organisations emerge, some of which supplement or even replace existing structures17. The term ´sustainability´ in their title refers to their long-term goals of addressing societal challenges and guiding systemic changes toward ecological resilience and social well-being while going beyond incremental improvements, seeking rather radical shifts to more sustainable socio-technical systems. The goals may vary depending on the circumstances the transitions happen in. Generally, a set of goals is promoted globally to create more sustainability, where sustainability is understood in 17 different contexts, which were formulated into the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the UN (compare Fig. 134). The SDGs are aimed at states, but companies, civil society and research are also explicitly encouraged to participate and derive their own specific goals from the SDGs.

Figure 1: The United Nations´ Sustainable Development Goals, Own illustration by W. Hell based on34

Scholars like Rotmans et al. (2001) define transitions aligned with the previous descriptions as “transformation processes in which society changes in a fundamental way over a generation or more” (p. 15), stating that they typically unfold over at least 25 years3. Smith et al. (2005) further emphasize the role of innovation and governance in transitions, stating that they are “long-term, multi-dimensional, and fundamental transformation processes through which established socio-technical systems shift to more sustainable modes of production and consumption” (p. 1491)35. To this, Geels (2011) adds the involvement of “changes in technology, user practices, markets, policy, cultural meaning and scientific knowledge” (p. 24)23. Markard et al. (2012) further elaborate that ST involve “far-reaching changes along different dimensions: technological, material, organizational, institutional, political, economic and socio-cultural” (p. 956)17. Loorbach et al. (2017) offer a more recent definition, describing sustainability transitions as “non-linear processes of social change in which a societal system is structurally transformed” (p. 600)36. In addition to the list of changes involved, Geels et al. (2023) also include markets and price incentives, as well as knowledge bases, consumption practices, business models, infrastructures and power structures37. These various definitions present ST as multilayered processes with a high complexity. They take a variety of dimensions and influencing factors into account and are deeply embedded in existing structures, which brings them both opportunities and challenges. The common thread across these definitions is the emphasis on fundamental, systemic change towards more sustainable societal configurations, highlighting the multi-dimensional nature of ST. In order to understand the properties of ST in greater depth, the core characteristics are taken up again individually below.

2.3.2 Key Characteristics of Sustainability Transitions

The various definitions of sustainability reveal many properties, some of which are recognized by several authors and are therefore considered particularly important. The key characteristics of ST are analyzed in more detail below. Here, multi-dimensionality, long-term perspective, non-linearity and complexity, challenges of change, experimenting and learning, and governance and policy were selected as overarching characteristics.

The multi-dimensionality of ST refers to the interconnected and complex nature of changes across multiple dimensions of socio-technical systems. This characteristic is widely recognized in the ST literature and has been considered by several authors, as in the previously mentioned definitions by Smith et al. (2005), Geels (2011) and Markard et al. (2012) among others17,23,35. Across these sources, the dimensions are broken down into six overarching categories involving technological, social, institutional, political, economic and cultural elements. Köhler et al. (2019) go into further detail and add the specific elements of markets, user practices, cultural meanings, infrastructures, industry structures and supply and distribution chains4. Multi-dimensionality means that changes must occur across all these elements in an interconnected manner. One of the core frameworks for managing ST, the Multi-Level Perspective (MLP) (compare chapter 3.4.1) conceptualizes transitions as interacting processes between three levels: Niche, Regime and Landscape, encompassing multiple dimensions at each of these levels. This features not only multiple dimensions but also multiple actors and stakeholders across different levels, which reflects the complex nature of socio-technical change38. More recent research has expanded on the concept of multi-dimensionality with Geels et al. (2023) discussing how transitions are unfolding at different speeds and depths across systems due to varying techno-economic developments and socio-political activities, which highlights the need to consider the interactions between different systems undergoing transition next to the multiple dimensions within a single system37. Although the multi-dimensionality covers many aspects and thus brings opportunities for research and practice, it also brings difficulties. It underscores the complexity of sustainability challenges and the need for coordinated, interdisciplinary approaches to understand transition processes and achieve systemic change2.

Another key characteristic of ST is its long-term perspective. The transitions are so comprehensive and require action at so many levels at different times that they often extend over decades. This equips them to address intergenerational challenges and achieve lasting transformations. While Rotmans et al. (2001) mention a time span of at least 25 years, Markard et al.

(2012) extend this to ‘typically 50 years and more’ (p.956)3,17. This characteristic is also set out in one of the core frameworks of managing transitions. In Transition Management (TM) (compare chapter 3.4.2), long-term thinking is described as a key element. More recent literature such as Köhler et al. (2019) continue to highlight the need for long-term perspective by translating transitions into concrete policy strategies with short- medium- and long-term goals4.

Additionally to being multi-dimensional, ST also have the characteristic of non-linearity, which means they do not happen in a straight process that can be explained by cause-effect interactions, but rather happen in an unpredictable sense that entails unproportional outcomes12. Their non-linearity is closely webbed to the previously described multi-dimensionality of transitions. The multi-dimensionality in turn creates great complexity which requires a multifaceted and interdisciplinary approach to address the pressing interconnected challenges of sustainability globally. A main aspect of this complexity is the interdependence across different systems. Systems such as energy, transport and food, where changes in one system can have cascading effects on others, which creates a web of interactions difficult to predict and manage7. This is acknowledged and studied within the complexity theory, which is essential for designing effective interventions to account for unintended consequences and therefore maximizing positive outcomes24. These transitions require the cooperation and collaboration between actors such as governments, businesses, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and consumers, which can entail conflicting interests and priorities, necessitating negotiation and consensus-building processes, to overcome the challenges of aligning goals and actions31. Their complexity makes them highly valuable but simultaneously difficult to achieve, posing as a driver and barrier simultaneously.

While change may bring opportunities, there are also challenges to face. Existing systems are often resistant to change. Path dependencies and lock-ins are therefore key features of sustainability transitions. These concepts are essential for understanding the challenges of transforming complex socio-technical systems towards more sustainable configurations. Lock-ins refer to self-reinforcing mechanisms that keep existing systems in place and are developed due to investments in infrastructure, market structures and consumer habits, all of which perpetuate unsustainable systems38. Lock-ins can lead to path dependencies, which describe how past decisions like investments influence and constrain future processes and choices, contributing to the entrenchment of these systems and the prevention of alternative solutions2,4. On the one hand lock-ins and path dependencies act as barriers for ST. On the other hand, understanding these mechanisms can facilitate learning how to overcome them and create new, more sustainable pathways.

Another characteristic of ST is the high relevance of innovations, experiments and the learning from them are central to transitions research. Innovations are further developed through experiments and constantly supplemented with new insights that are once again tested in experiments, fostering new innovations. This will be taken up in more detail in the Strategic Niche Management (SNM) framework in chapter 3.4.4.

So far, the realization has been reached that sustainability transitions are not simply marketdriven processes that happen in linear fashion, but require active managing and steering, coordinated by various actors. Markard et al. (2012) note that a broad range of actors is expected to work together in guided transitions, emphasizing the relevance of governmental and policymaking bodies as key characteristics in this guidance of ST31,35,39. Kern and Rogge (2018) further argue that in order to provide long-term direction, policy mixtures of multiple policies must be analyzed, so-called policy mixes31. Literature has expanded on these concepts with Köhler et al. (2019) discussing the governance challenges of ST, emphasizing the challenge of coherence in transition efforts, suggesting the coordination across different governance levels and mapping of responsibilities as a solution approach4. In summary, it is clear that all definitions emphasize a long-term, systemic transformation, but place different emphasis on technological, institutional, or social dimensions.

2.3.3 The Process of Sustainability Transitions

Various authors have attempted to describe how these transitions actually take place. The general consensus on a conceptual level is that transitions go through different phases.

The most frequently cited model of transition phases is that of Rotmans et al. (2001), in which four phases were identified3. The first one is predevelopment, a phase of dynamic equilibrium where the status quo does not visibly change. This phase is characterized by experimentation, small-scale projects and pioneers learning about performance, acceptance and feasibility of radical niche innovations. This is followed by a take-off phase where the process of change begins as the system starts to shift. Here, radical innovations reach support in one or more market niches where they gain consolidation. In the following phase of the breakthrough, structural changes become visible through an accumulation of interactive changes across socio-cultural, economic, ecological and institutional levels. Within this phase, collective learning and embedding processes lead to diffusion into mainstream markets, accelerating the transition. When the transition overcomes all hurdles along the way and the speed of change finally decreases, the stabilization phase is reached where a new dynamic equilibrium is set in place3.

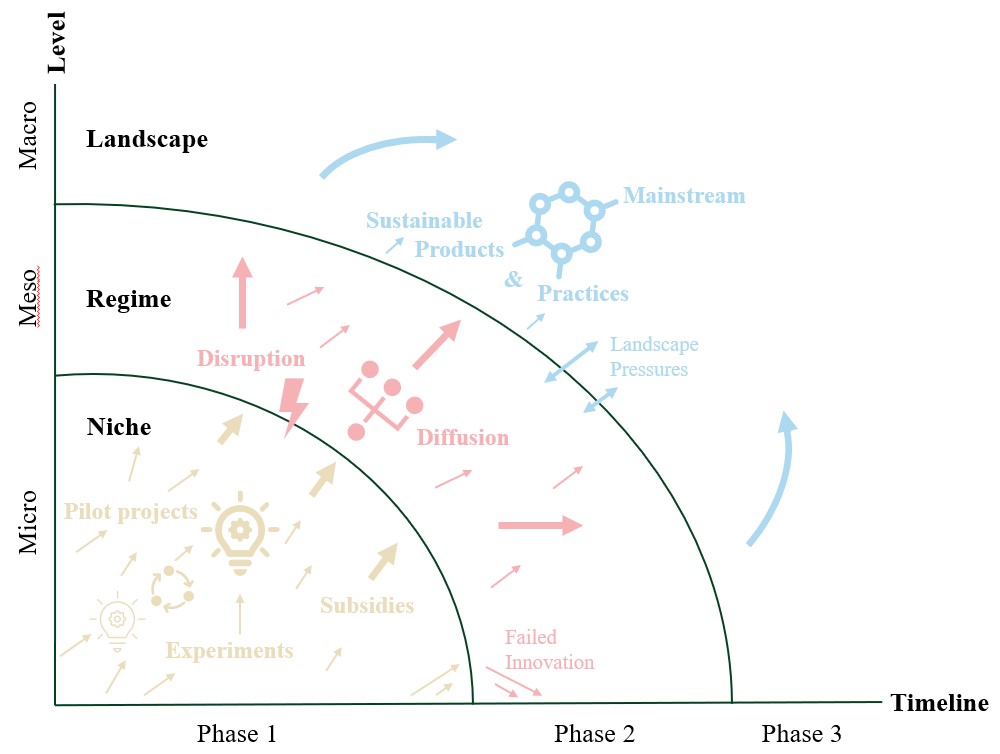

While the four-phase model has been adopted widely in the field of ST research, more recent literature proposed a slightly modified model. Kanger and Schot (2016) propose that transitions unfold in three phases, visualized in Figure 2:

Figure 2: The process of sustainability transitions simplified, Own illustration by W.Hell based on and substantially adapted from38

Phase 1, the start-up phase: Niche innovations get developed and experiments are carried out. These niche innovations are further stimulated through subsidies for research and development, pilot projects and public procurement. This phase can be repeated several times by making further additions through learnings from experiments and it can span several decades.

Phase 2, the acceleration phase: Proven innovations begin to scale up and diffuse. This is supported by the adoption of further subsidies, e.g. capital grants and infrastructural investments. Simultaneously, the innovations start to destabilize the existing unsustainable system through pricing instruments and regulations for example.

Phase 3, the stabilization phase: The innovative sustainable products and practices develop into mainstream and a new dynamic equilibrium is reached. The focus of the policy shifts to maintaining and optimizing the new system.

While these share similarities with the conception of Rotmans et al., they differ in conceptualization. Kanger and Schot´s model combines the predevelopment and take-off phase into a singular start-up phase, which reflects a more streamlined view of the early transition process (compare Figure 2´s Phase 1). The acceleration phase (compare Figure 2´s Phase 2) corresponds to Rotman et al.´s breakthrough phase, highlighting the critical time period of rapid change and upcoming competition between niche innovations and existing regimes before a new systemic equilibrium is reached in the stabilization phase (compare Figure 2´s Phase 3). The three-phase model simplifies the process of transitions and allows for easier integration with other frameworks and concepts in ST research. It attempts to provide a more concise understanding by considering the most critical aspects reduced to emergence, acceleration and stabilization in detail3,40.

It is important to note that both models only represent the process of sustainability transitions in a very simplified manner. While the general phase model remains influential, the choice between the models often depends on the specific context and focus of the research or aim of implementation41.

2.4 Core Frameworks for Management of Sustainability Transitions

Each of these frameworks is comprehensive and cannot be addressed explicitly due to its scope. A brief overview will be provided to ensure a basic understanding; it is recommended to consult the extensive literature available on the respective frameworks.

These numerous frameworks on sustainability transitions management reflect the interdisciplinary nature of sustainability research, drawing from multiple sources such as sociology, economics, political science and innovation studies. They aim to provide structured ways to examine how transformative changes occur within socio-technical systems and offer practical tools to promote sustainability transitions. Some frameworks are foundational, others add to separate directions of ST. “Transitions management” in this context is referring to the general approaches and processes of managing ST and not specifically meaning the same-named framework Transition Management itself, which is one of the four core frameworks of transitions management and will be abbreviated by TM in the following.

Identified as core concepts on transitions management are the Multi-Level Perspective, Transition Management, Technological Innovation Systems and Strategic Niche Management. While all of these frameworks are widely recognized in the ST research field, their scope and level of adoption differ. This is rated more relevant than their chronological order, which is why they will be presented in descending order of their respective range in the following.

2.4.1 Multi-Level Perspective

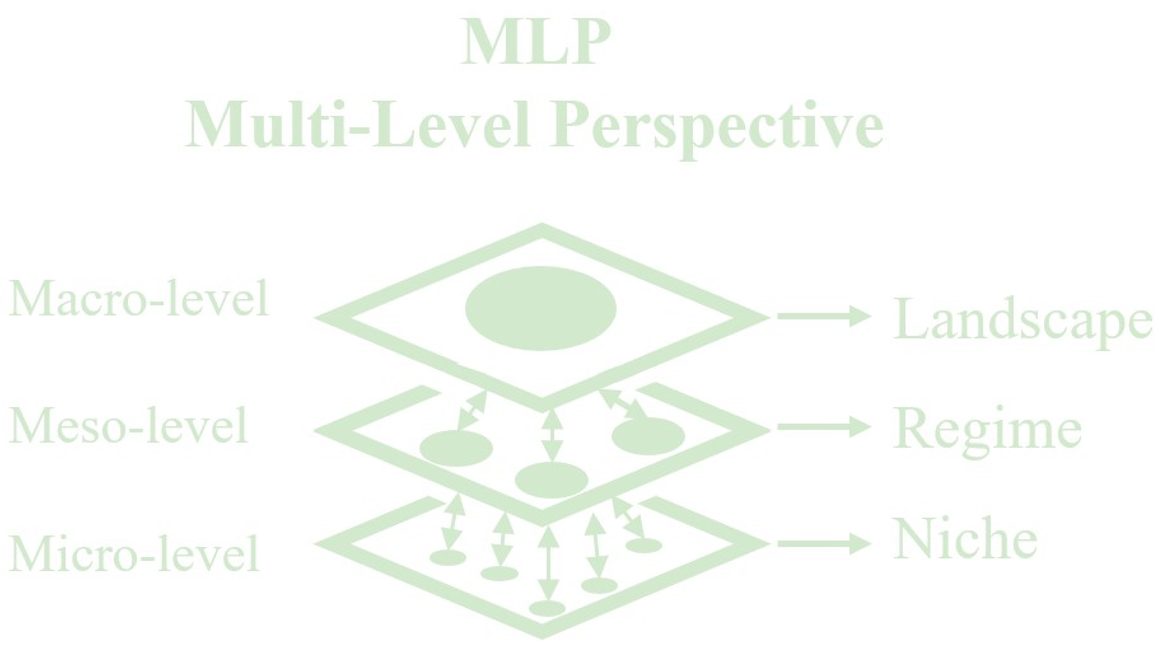

The Multi-Level Perspective (MLP) is a dominant and widely used framework in sustainability transitions research and states that transitions occur through processes of interaction within and between three levels of analyses: the micro-, meso- and macro-level. It further analyzes transitions organized into a socio-technical system where they unfold across niches (innovation spaces), regimes (dominant systems) and landscapes (external pressures)6,42. The objective is that niche innovations challenge established regimes under landscape pressures, eventually provoking transitions of entire systems17.

Figure 3: The Multi-Level Perspective simply illustrated, Own illustration by W. Hell based on43

On the micro-level, niches are conceptualized as protected spaces for experimentation. Radical innovations can develop and mature in niches until they are tangible enough to attempt to challenge and disrupt regimes. These spaces can be research projects, pilot programs, startup ecosystems or experimental policy initiatives among others that incubate sustainable alternatives12. Within these niches, innovations can gain traction through learning processes, network-building and policy support4. A known example are electric vehicles (EVs), which were initially a niche innovation that gained traction through support by subsidies and Research and Development (R&D) incentives until they were tangible enough to compete with existing internal combustion engine vehicles.

On the meso-level, regimes represent dominant systems of technology, policy, and behavior that structure the current industries and daily life6. These regimes are collectively reinforced by government policies, businesses, consumer behaviors and industry standards and benefit from entrenched investments and institutional stability, which explains their high resistance to change. The adoption of sustainable alternatives is thus often slowed down or blocked by path dependencies, vested interests and institutional lock-ins at this level17. Path dependencies refer to historical investments and established systems that constrain future choices, like the dominance of fossil fuel-based infrastructures for example. Business and stakeholders have vested interests in their profitability, market position and competitive advantages, all of which they fear may be threatened by sustainability transitions, which explains their resistance to them31. Institutional structures such as regulatory frameworks and policies may create stability, but they also reinforce unsustainable systems by creating lock-ins4. Lock-ins here are market and policy failures that are “locked in”, meaning they are deeply rooted, they make it difficult to introduce new technologies, even though these bring obvious advantages. These lock-ins can be technological, e.g. in infrastructure, institutional, such as regulations and organizational structures, or behavioral, such as long-established patterns of behavior44.

On the macro-level, landscapes endure external pressures that are largely beyond the control of individual actors, for example climate change, geopolitical shifts and economics crises. As these landscape pressures intensify, they can destabilize existing regimes and make them more vulnerable to disruption, creating windows of opportunity for transitions through niche innovations17.

With this spatial and temporal division, the MLP states that transitions do not happen overnight, but in a multi-phase transition process within the three levels.

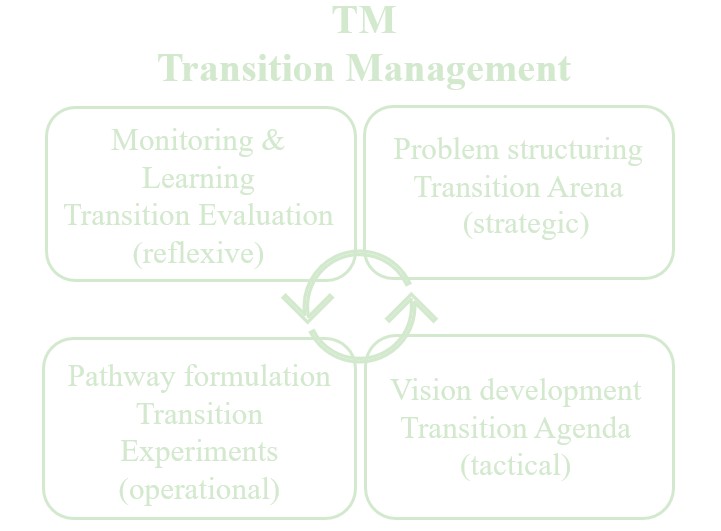

2.4.2 Transition Management

A systemic governance approach is given by Transition Management (TM), which emerged as a practical response to the growing multiplicity of sustainability challenges, drawing from complexity science, innovation studies and participatory governance theories7. It aims to steer longterm, complex transitions toward sustainability through visioning, experimentation and iterative learning and draws upon the multi-level conceptualization of socio-technical change, acknowledging that sustainability issues require transformative, non-linear and participatory processes that involve multiple actors for them to be solved3,7.

In TM, multi-stakeholder platforms are created, where frontrunner actors can collaborate to develop long-term visions for sustainability. These platforms are called transition arenas and the frontrunners involve researchers, policymakers and businesses to foster a shared understanding of sustainability issues and co-developing transition pathways7,8.

The basic principles are formulated into an operational model for implementation, the transition management cycle, shown in Figure 4, which structures transitions into a simplified cyclic process. First, it structures the problem and organizes the transition arena (strategic). Then, it develops a vision for the transition agenda (tactical), deriving a pathway formulation while establishing experiments and mobilizing the resulting networks (operational) and monitoring and learning lessons from the transition experiments (reflexive). Finally, it makes appropriate adjustments in vision, agenda and execution3,7,45,46.

Figure 4: Transition Management simply illustrated, Own illustration by W. Hell based on47

The transition experiments in the operational part of the TM cycle are promoted as a key driver by allowing innovative solutions to be tested in protected spaces before being scaled up4. Through these pilot projects it is possible to gain insights into how new business models, governance structures and technologies interact with the existing systems7. The processes of the cycle must not to be interpreted as a fixed plan and instead it is important to understand that transition strategies must be continuously reassessed and modified based on the evolving societal needs and external pressures, meaning the cycle can be followed multiple times, each time adding up the learnings from the experiments. Noticeable in this approach, TM shows its link to the MLP with recognizing that transitions occur on the different levels of niches, regimes and landscapes6. Understood in the MLP context, strategies of TM can be adapted as transitions move from niche experimentation to regime destabilization and systemic transformation7,38.

The institutionalization of TM hit a milestone when it was integrated into the Netherlands environmental policy through the Fourth Dutch National Environmental Policy Plan (NMP4), which adopted TM as a central tool for addressing persistent challenges such as climate change, resource scarcity and social inequality3. Since its introduction, TM has garnered both support and criticism, which has led to a rich interdisciplinary debate. The concept has evolved significantly over the last decade and has gained empirical support in publications which reflects a developing consensus among scholars regarding the value of TM in governance practices46.

TM and MLP complement each other in structuring and steering sustainability transitions. While MLP provides the analytical lens to understand how transitions unfold across different levels (niches, regimes, landscapes), and where a transition currently stands (e.g., whether it is in the stage of niche innovation, regime destabilizing or in the stage of landscape pressure driving systemic change), TM offers the governance approach to actively shape these processes and helps decision-makers in formulating pathways, vision-building, and policy interventions to accelerate these changes6,7,45.

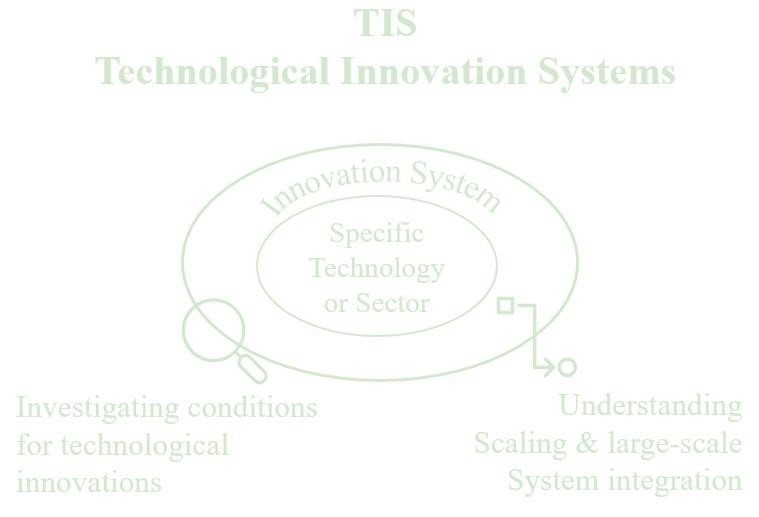

2.4.3 Technological Innovation Systems

The Technological Innovation Systems (TIS) framework shifts the focus to the conditions enabling or hindering technological change. It is a widely applied approach for analyzing the development, diffusion and the scaling of new technologies in the context of ST, providing a structured way to assess how actors, institutions, networks and policies influence the success or failure of technological innovations in transforming socio-technological systems48,49. Unlike the MLP, which as stated in 3.4.1, focuses on systemic transitions across different levels of socio-technical structure, TIS is narrowing its scope to specific technologies or sectors, and investigating the necessary conditions for them to be integrated into the market and prove systemic impact, as illustrated in Figure 517,48. In Figure 5, a specific technology or sector is shown in the center, surrounded by an innovation system with a magnifying glass symbolizing the investigation of the conditions and an arrow symbol to display the understanding of the scaling and overall system integration. This model is specifically relevant for green technologies, circular economy innovations and low-carbon solutions, as it helps businesses, policymakers and researchers understand what barriers and drivers exist for scaling sustainable technologies4.

Figure 5: Technological Innovation Systems simply illustrated, Own illustration by W.Hell based on17

To determine the necessary conditions for technological innovations, the TIS framework, as proposed by Bergek et al (2008), identifies seven key system functions based on several literature reviews and empirical studies, which serve as indicators of whether an innovation has the knowledge base, market support, policy alignment and actor engagement to potentially scale successfully. The functions are described and refined by modern supplementary literature in the following49.

The first key function of TIS is the creation of knowledge related to innovation. Research and development activities, collaboration between scientists, and technological advances contribute to strengthening the knowledge base. A broad and strong knowledge network allows firms to share their best practices, reduce uncertainty and increase learning effects4.

The second function emphasizes the importance of entrepreneurs and Start-ups in driving sustainable technologies. Hekkert et al. (2007) have described this function as “Entrepreneurial Activities”(p. 415) and state that for turning potential of new knowledge and markets into concrete actions, entrepreneurs that take advantage of business opportunities are essential. Furthermore, they note that early-stage investments and the variety and extent of experimentation are indicators of entrepreneurial activities like innovation activity and market responsiveness50.

Building on these foundational elements, the literature states that there is an influence on search direction which shows there are external factors that influence actors and their investment decisions in ST. It is noted that a critical number of organizations need to recognize the entrepreneurial opportunities in the new system and enter it, which is prompted by external factors such as sufficient incentives or pressures49. The pressures can come from governmental policies, environmental regulations and from consumers and NGOs39. In addition, the European Union’s (EU) Green Taxonomy, sustainable finance policies and carbon pricing mechanisms are exemplary institutional mechanisms that steer investments into low-carbon solutions emerging from TIS.

Another function is based on the hypothesis that for technological innovations to succeed, new markets must be created, and the financial, human resources and complementary assets must be effectively allocated and mobilized. This market formation and resource mobilization include the procurement of public and private funding, the facilitation of access to the knowledge base and skilled workforce, and the development of the necessary infrastructure17. A lack of these investments can hinder innovations by creating a valley of death, where once promising technologies fail before reaching market maturity4.

The TIS framework also highlights the need for policy adaptation, social acceptance and standardization in the industry to overcome regulatory and institutional barriers49. Resistance from incumbents and a rigid regulatory environment often prevent emerging technologies from integrating into mainstream markets4.

The final function focuses on positive externalities which contribute to the advancement of sustainability transitions. When Technological Innovation Systems are successful, they create spillover effects other sectors and industries can benefit from. They can be knowledge spillovers, the development of complementary technologies, and increased awareness of sustainable solutions4.

Recently (2020), Markard has added to the literature of the field of TIS research, suggesting that scholars have previously focused on early rather than mature stages of TIS with the aim to fill that gap. His literature further introduces the hypothesis that a TIS passes through four stages of development, which form the key elements of the TIS life cycle framework. The first stage includes the formation of an innovative technology, followed by institutionalization and rapid growth of the technology, subsequently maturing until a point of destabilization, decline and eventual extinction. This further investigation provides the field with an important improvement of conceptual development that addresses the phase of transition in which innovative technologies diffuse widely, while unsustainable technologies eventually decline51.

Although the TIS framework is widely used in the literature, its transferability to other than technological innovation contexts remains controversial. This framework has been used to analyze the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy and the electrification of transport among others, proving its value in analyzing sustainability transitions and as a tool for researchers and policymakers.

2.4.4 Strategic Niche Management

The analytical and governance framework Strategic Niche Management (SNM) originated in the 1990s with Kemp et al. (1998) defining it as “the creation, development and controlled phase-out of protected spaces for the development and use of promising technologies by means of experimentation, with the aim of (1) learning about the desirability of the new technology and (2) enhancing the further development and the rate of application of the new technology” (p. 186)11. It explores how innovations can emerge and diffuse within protected environments, known as niches12. Scholars like Arie Rip, René Kemp and Johan Schot have made interdisciplinary contributions, shaping the special approach of SNM to explain how radical sustainable innovations can be protected in niches and nurtured through the three core processes experimentation, stakeholder engagement, and learning until they gain enough momentum to overcome the barriers and disrupt dominant regimes (see Figure 6), eventually contributing to systemic transformations12,22,52. Scholars like Hoogma (2000) further identified processes that are more specific and occur within niches: the so-called `internal niche processes of articulation and coupling of expectations, facilitating learning processes and formation of social networks12,53. These internal processes are the means by which the previously mentioned core processes are realized within the niche. SNM is particularly relevant within the MLP, where it operates on the niche level, but also emphasizes the concept of niche-regime interactions, where niche innovations are gradually aligned with regime structures which is stated to potentially lead to broader systemic changes (compare chapter 3.4.1)12.

Figure 6: Strategic Niche Management simply illustrated, Own illustration by W. Hell based on52

The most critical aspect of SNM is the existence of protected spaces (niches). Niche protection allows for the core process of experimentation to unfold, enabling actors to test innovative business models, user behaviors or governance structures before exposing them to market pressures52. Mechanisms to facilitate protection include financial support in forms of government subsidies, investment incentives and R&D funding to sustain innovation development, regulatory support in forms special policy frameworks that provide preferential treatment for emerging technologies, and support in the market in forms of shielding through procurement programs and niche markets that ensure a demand for sustainable innovations early on11,12,52.

Whether these experiments are successful or fail, the actors take away lessons regardless. The need for continuous learning and iterative development is also stressed as a requirement for ST by SNM. The learning can be technical, which could mean refining product design, efficiency and reliability, or social, such as understanding and anticipating consumer behavior, adoption patterns and resistance to change, or institutional, e.g. identifying policy gaps and designing regulatory frameworks to support niche scaling11,12,52. Additionally, expectation management was found to be a crucial part of SNM, contextually one of the internal niche processes, since overstated claims about new technologies could lead to disillusionment, while realistic goalsetting is set to ensure long-term support from investors and policymakers52.

For the success of niche innovations, SNM emphasizes the importance of multi-actor networks where stakeholders such as businesses, policymakers, researchers and civil society engage52. These networks serve functions like knowledge exchange, which facilitates the transfer of technical expertise and experiment developments across stakeholders, political influence that can enable niche actors to advocate for favorable regulations and policy incentives, and market development in forms of connecting sustainable innovation providers with early adopters and scaling partnerships11,12,52. They are essential for overcoming institutional barriers and aligning niche innovations with broader sustainability agendas12.

SNM is closely related to different concepts in the field of ST research, such as `Strategic Niche Experimentation` and `Transition Experiments`, which show similarities in focus on protected spaces for innovation but differ in their specific scope and methodology. While a contextual understanding of these concepts is given in this chapter, they will not be further elaborated to not go beyond the thesis´ scope.

While TM focuses on governance strategies and TIS examines the innovation conditions across a technological system, SNM provides a bottom-up approach for nurturing and scaling sustainable alternatives for a successful diffusion12. The SNM approach has been widely applied in various sectors, e.g. renewable energy, electric mobility, sustainable agriculture and circular economy models where it has facilitated learning, actor collaboration and policy alignment52.

In summary, the literature states that these four core frameworks provide complementary approaches to sustainability transitions. The continuous development of further frameworks and additional findings has helped to come closer to understanding the complexity of the ST field, which cannot be captured by one single framework17. Systemic dynamics (MLP), governance processes (TM), technological development (TIS) and niche experimentation (SNM) have been studied and used to address the different stages and challenges of systemic change. They do not necessarily have to be applied simultaneously, but rather overlapping, depending on the stage the transition is at and the barriers it has to overcome. In early-stage innovation, it makes sense to apply SNM and TIS to foster niche innovations and ensure the systemic conditions for scaling12. To analyze and diagnose the transition, it is advisable to use the MLP to understand the consequences of the transition considering the interactions between niches, regimes and landscapes23. The MLP and TM can then be used together for governance and strategy development to guide transitions through policy, stakeholder engagement and long-term visioning7. TM and TIS can ultimately be considered together for scaling and market formation to ensure that sustainable innovations get the necessary support for widespread adoption9.

As the field continues to develop, complementary frameworks for management approaches have been introduced, of which those that specifically relate to businesses are covered in the chapter 3.4.5 below.

2.4.5 Complementary frameworks

Multiple complementary frameworks have emerged in recent years that lay their focus on certain fields. These frameworks are showcasing the evolving nature of ST research, expanding beyond the four core frameworks to address specific contexts in business, policy and societal domains. Since there are a large number of complementary frameworks, not all are listed here. The following were selected to provide a policy perspective, one to address the equity factor, and one to address climate change. In the following, these frameworks are briefly presented.

The policy design framework aims to guide policymakers in designing effective ST strategies17. The Just Transition Framework focuses on equitable ST and prioritizes equity in the transition process25. The Regional Sustainability Transition Framework was developed by the European Union to support ST in regional planning in order to strategically accompany the ambitions of the European Green Deal through cohesive policy54. ST research has increasingly recognized the pivotal role of businesses in shaping systemic change55. While comprehensive analytical and governance approaches have been provided by the core frameworks, mechanisms on how businesses can integrate sustainability into their core strategies have not yet been clearly stated in them. In response to that, frameworks for corporate sustainability transitions have emerged to guide businesses in the process of adapting their core strategies, operations, value chains and market positioning to align with sustainability agendas. A direct complement to the core framework TM for example, is the Business Transition Management framework by Loorbach and Wijsman (2013), which has adapted the principles of TM to the corporate context56. The authors trace the evolution of sustainability in the business context, emphasizing the shift from corporate social responsibility (CSR) and environmental compliance to more transformative business strategies that integrate sustainability into core operations. This reflects the co-evolution between businesses and societal systems, where both adapt to changing environmental, economic and cultural conditions. Elements of MLP, SNM and TIS are included in the Sustainable Business Model and Circular Economy Business Models which have been developed and expanded by several contributors, as they consider how companies can drive niche innovations and contribute to the shift of a regime57. There are numerous other frameworks for STs that are specifically tailored to businesses. These are not all to be listed but indicating the emphasis placed on businesses in ST research and the sustainability debate.

By applying any of these listed frameworks in a strategically coordinated and appropriately combined manner, businesses, policymakers, and researchers can ensure that innovations move beyond experimental phases and lead to systemic transformations toward sustainability. The effectiveness of these frameworks depends on their flexible application, tailored to the specific needs of the sector, technology, and socio-political environment in which the transitions occur.

2.5 The role of businesses in Sustainability Transitions

For a long time in the history of businesses, the focus was on how companies innovated and created wealth. However, there has since been a movement of research focusing on the environmental consequences of economic growth. The evolution of corporate strategies for businesses in response to environmental, social and economic challenges is explored by Bergquist (2017)58. During the industrial revolution, businesses operated for economic growth with little concern for environmental or social impacts. Following the rapid expansion of industries, public awareness of environmental degradation, resource depletion, pollution and social injustice grew in the early 20th century. The 1960s and 70s marked a turning point with environmental movements and regulatory interventions pressuring businesses to acknowledge their ecological footprint and shape their practices accordingly. John Elkington´s Triple Bottom Line (1997) then introduced the people, planet, profit framework which influenced businesses to measure success beyond financial profits59. After a complex and often contradictory historical relationship between businesses and environmental sustainability, businesses play a crucial part in Sustainability Transitions in the 21st century.

Business models have increasingly been recognized as significant within the context of ST by scholars like Köhler et al. (2019)4. The impact of business models on transition dynamics was highlighted by Bidmon and Knap (2018), who illustrated the role of businesses as both facilitator and barrier to change within a socio-technical landscape55. They state that “firstly, [business models] can reinforce the existing socio-technical regime, hindering transitions by bolstering current stability.”, “secondly, by acting as intermediaries, business models expedite transitions by aiding in the stabilization and breakthrough of technological innovations.” and “lastly, as non-technological niche innovations, new business models contribute significantly to the emergence of new regimes, independent of technological advances.” (P. 909-910), while on the other side they also highlight that the discourse on ST challenges businesses to rethink their model and their role in society55.

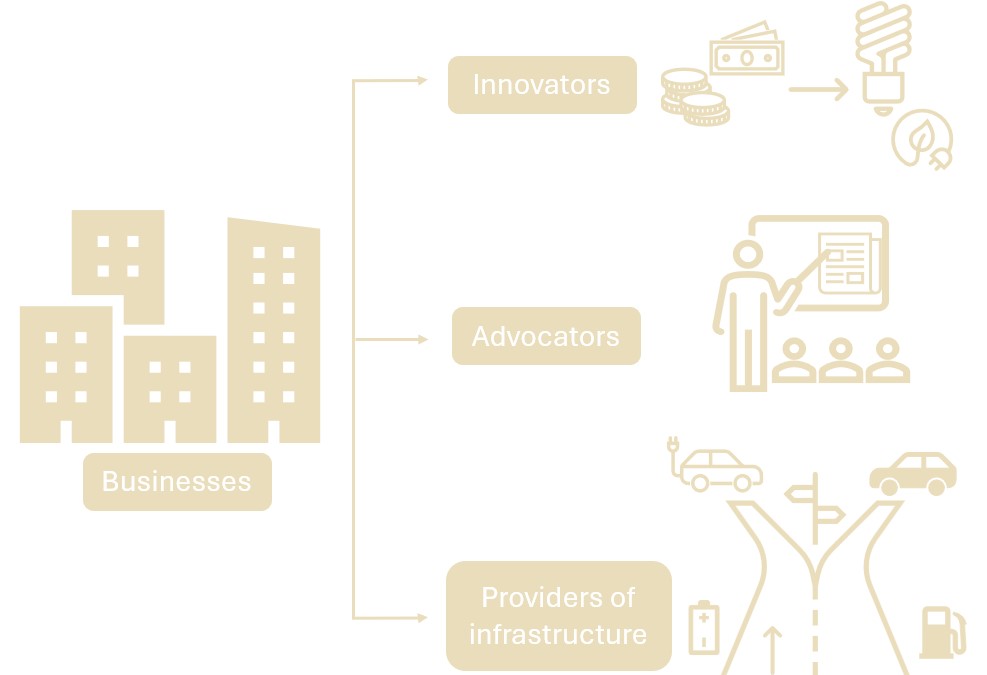

Companies are interesting for the field of ST research and implementation because they have resources, skills and political power. A fundamental observation is that companies act as drivers of transitions in different roles. The importance of the roles they can assume correlates with their global market influence. With actions like investing in new and green technologies, implementing modern circular economy models and applicating renewable energy solutions, they act as innovators. By implementing and promoting new policies successfully and complying with sustainability regulations, they act as advocators. By developing and providing the necessary infrastructure, they metaphorically and literally pave the way (compare Figure 7). These actions enable corporations to take influential and leading roles in the field of ST.

Figure 7: Visualization of roles businesses take on in ST, Own illustration by W.Hell

When it comes to scope, a distinction can be made between large corporations and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Larger companies have abundant resources at their disposal and therefore more financial possibilities and influential authority to drive sustainable initiatives. However, due to their size, they have more complex supply chains, more serious environmental impacts and therefore a higher scrutiny of stakeholders. Even though the environmental footprint of individual SMEs may be small, their overall impact is significant. Due to the large number of SMEs in overall enterprises, their cumulative share of emissions covers 63.3% (status of 2022) of all Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions in the population of enterprises60. Thanks to their smaller size, SMEs are more flexible and able to adapt and implement sustainable practices faster, yet the barriers they face are limited financial and experiential resources. In summary, it can be seen that large and small and medium-sized businesses play important roles in ST, whereby large corporations can lead industry-wide initiatives and SMEs can drive innovation and local implementation61.

This kind of influence is accompanied by responsibility. Governments and financial markets demand transparency from businesses in environmental, social and governance reporting, while stakeholders expect companies to act on sustainability challenges like climate change and social injustice, which pressures businesses to make sustainability a core business priority and reinforce actions towards transitions58. ST also have a significant impact on businesses, both supportive and challenging. ST are changing operational landscapes and market dynamics, forcing businesses to adapt to updated regulations, shifting consumer preferences and technological advances. An understanding of ST enables companies to mitigate risks associated with environmental and social challenges such as resource scarcity and reputational damage, while capitalizing on opportunities in green markets. ST therefore acts as a lever for companies to maintain a leading role in the evolving marke62.

Conclusively, businesses are responsible for optimizing their internal processes as well as contributing to systemic sustainability. Sustainability transitions are of particular importance for businesses as they act as catalysts for business transformation through requiring companies to fundamentally rethink their strategies, business models and operations. Conversely, businesses themselves play a key role in sustainability transitions. They have a complex and multifaceted relationship, significantly influencing one another. Businesses can shape and be shaped by ST.

2.5.1 Management framework´s perspective on the role of Businesses

The core frameworks analyzed in the Literature Review provide implications particularly for businesses on how to manage STs. Their points of view of the MLP, TM, TIS and SNM are shortly summarized in the following. The results are again shortened to reflect the extent of the thesis.

The MLP provides approaches for companies divided into companies in regimes, i.e. established companies, and companies in niches, such as Start-ups. For the former, the recommendation is to pursue a dual strategy of simultaneously optimizing existing business models and processes, for example by increasing efficiency through carbon dioxide reduction in production, and promoting and adopting niche innovations to ensure the resilience of the company63. Companies in niches are advised to use these for pilot projects and to cooperate with stakeholders such as NGOs or politicians to achieve economies of scale49.

Transition management (TM) encourages companies to rethink their long-term strategies in order to move on from short-term profit maximisation towards a model of socio-ecological value creation56. To achieve this, TM recommends companies need to embed sustainability into their core strategies by transitioning from linear, resource-intensive production models to circular and sustainable business models46. Rather than making incremental improvements, companies are encouraged to align their strategies with long-term sustainability visions and actively contribute to systemic change31. A central aspect of TM is corporate participation in transition arenas, where companies engage in public-private partnerships and cross-sector collaborations to co-create sustainability pathways7. Participation in such arenas fosters knowledge sharing and strategic alignment with regulatory frameworks, enabling companies to anticipate market shifts and regulatory changes while fostering closer relationships with governments, NGOs and consumers56. TM further highlights that firms must actively engage in pilot projects and sustainability experiments to test innovative ideas before scaling them up4. Loorbach and Rotmans (2010) state that companies that prioritize sustainable research and development (R&D) and invest in emerging markets will gain a competitive advantage as transition landscapes evolve46. Companies are further advised to embed sustainability into their corporate governance structures in order to future-proof their operations against regulatory risks and the changing consumer demands, while simultaneously strengthening their market position31. However, transitions remain dynamic processes and TM emphasizes the need for continuous monitoring and adaptation to systemic changes. The recommendation on this matter is for firms to regularly assess their transition progress and adjust their strategies as technologies, policies and market conditions evolve7. By integrating these TM principles into their strategic frameworks, companies can become active agents of systemic change, not only contributing to the broader societal transition towards sustainability but also securing long-term economic viability in increasingly sustainability-driven markets.

TIS suggests that companies in emerging sustainable industries need to focus on building knowledge networks, participating in pilot projects, and attracting investment to develop and scale their innovations. Businesses should first invest in R&D and knowledge-sharing networks to stay at the forefront of technological advancements39. Engagement with universities, research institutions, and innovation clusters then provides businesses with access to insights that can be used to strengthen their competitive advantage4. Like the other frameworks, TIS research also found that firms must align themselves with market-forming mechanisms and ensure that their products and services benefit from policy incentives, subsidies, and changing consumer demand39. Successful firms proactively pursue a favourable policy environment and work with stakeholders to create regulations that promote sustainable innovation, rather than waiting for regulations to be introduced46. As with any framework, TIS emphasizes the importance of constantly monitoring systemic developments such as policy and regulatory changes and evolving sustainability standards, and that companies can only gain a competitive advantage by keeping abreast of the latest sustainability trends4.

In addition to similar recommendations as the other frameworks, SNM provides more specific approaches for companies in niche spaces. It suggests for businesses to use support programmes to secure the development phases and an early involvement of customers, especially lead users, to increase market acceptance64. Expectation management also plays a role here, whereby transparency of objectives can increase investor confidence11. SNM research also leads to the recommendation to develop scaling strategies, whereby synergies between complementary niches should also be recognised and used (e.g. electric vehicles and smart grids)11,64.

2.6 Limitations and Future research directions

During the extensive research into the topic, a number of limitations and future research directions emerged, which are described below. As many areas that have a part in ST research have only been touched on or omitted so as not to exceed the scope of this thesis, the same applies to the limitations.

2.6.1 Limitations

Rotmans & Loorbach (2009), Loorbach (2010) and Geels et al. (2023) all mention the limitations brought about by the great complexity of ST7,24,37. Due to the complexity, consequences can follow in several dimensions and therefore are difficult to foresee and calculate. The longevity of ST poses a limitation because the long timeframes, which often span over decades, complicate the prediction of said consequences and outcomes and the development of appropriate interventions even further.

Another major limitation in the form of uncertainty, path dependencies and general resistance is posed by the involvement of multiple actors in different sectors, as inconsistencies between sectoral and cross-cutting policies hinder the alignment of transition efforts between different domains and governance levels65.

In addition to Rotmans & Loorbach (2009) and Geels et al. (2023), Loorbach and Wijsman (2013) also mention the criticism that ST research is based on several disciplines, but that there is no uniform theoretical approach that covers all perspectives24,37,56. They also criticize the fact that although some of the very detailed management frameworks overlap in their concepts, they lack integration, which leads to fragmented research. The lack of interdisciplinary collaboration in transition governance contributes further to fragmentation, which complicates practical implementation. They additionally emphasize that the fossil fuel industry, large corporations and established political structures delay transitions by lobbying against policy changes or regulations. Existing and developing power imbalances and the active resistance of interest groups are not always adequately taken into account in management frameworks.

In general, the influence of power in the overall sustainability debate is a major limitation that is not always obvious and is likely to be exacerbated by current political developments. Negative consequences for climate policy globally can be expected after the election of the new candidate for presidency of the United States of America (USA), who signed the decision to withdraw the USA from the Paris Climate Agreement on his first elected day66.

Further theoretical limitations are posed by the divide between socio-technical and socio-ecological transition theories, as many approaches still prioritize technocentric over ecocentric views. Their focus is on technological solutions, partly without adequately addressing the social and ecological dimensions which could lead to the creation of new problems due to narrow focus67.

There are also several methodological limitations. The lack of comparative studies, which impedes capturing the whole complexity of sustainability challenges, clarifies the need for more diverse and complementary methods. Transitions are long-term processes, yet the research field lacks longitudinal data, as most empirical research on ST relies on short-term case studies, which causes a dis-alignment of the research timeframes with the temporal patterns of complex sustainability challenges68.

Moving to the challenges of practical implementation, which will be covered in chapter 4, transitions are very context-dependent, so frameworks are difficult to translate across diverse contexts, especially in developing countries with different socio-economic conditions that the frameworks suggest. The majority of case studies focused their investigative study in European countries and thus cause a limitation of understanding those contexts outside of Europe with different institutional and economic conditions.

2.6.2 Future Research Directions

In order to work towards overcoming the barriers and limitations described in this thesis, many authors in the field provide recommendations and directions for future research.

Köhler et al. (2019) suggest the geographical and sectoral scope of case studies should be expanded broadly. Furthermore, the role of the civil society, whole cultural shifts as well as everyday practices in driving transitions should be investigated. Since systems can be interconnected, the interplay between multiple transition pathways should be explored across them. For assessing the effectiveness of governance frameworks and policies, further tools and methods need to be developed. The authors also highlight the need for more research on the acceleration and stabilization phases of and the interactions between transitions. ST research has been criticized for not addressing issues of justice, equity and inclusion enough, to which Köhler et al. recommend taking ethical aspects and just transitions into account in future research (Köhler et al. 2019). An increased focus on the spatial aspects of transitions including urban and regional transitions as well as more transdisciplinary research to bridge academic and practical knowledge is advocated for by Loorbach et al. (2017)36.

Recent literature demonstrates significant progress in addressing many of the listed gaps. Geels et al. (2023) for example employed diverse methodologies to study the influence of social innovation, cultural dynamics and non-state actors as well as everyday practices on transition pathways69. They further focus on the previous discussed interdependencies between transitions in different sectors and also foreground issues of just transitions. While substantial progress has been made by Geels et al. (2023) and further researchers in order to address the research gapy identified by Köhler et al. in 2019, some challenges and the need for a complete and unified research remains.

The recommendations and indications from various authors regarding future research directions in sustainability transitions can be summarized into broad suggestions. These include the need for broader and more interdisciplinary frameworks that enhance the applicability and better capture the complexity and vast scope of the field. The large number of frameworks makes it difficult to review and it would be advisable to create a guide to the application of certain frameworks or to generalize the many frameworks for a compact, controlled approach. Future research should address the interplay between multiple transition pathways across interconnected socio-technical, socio-ecological and socio-economical systems, while also integrating the role of society and the connection between cultural shifts and sustainability transitions. Additionally, non-technological innovations require further investigation. Expanding the geographical and sectoral scope of studies, particularly in underexplored fields such as politics, education, healthcare, etc. and ST in non-European geographics, particularly the Global South, are identified as crucial areas for future inquiry4,17,70.

3 Practical Implementation

Research has developed many consistent theories to expand the understanding of far-reaching sustainability transitions and how they can be implemented. In reality, there are some factors that can drive these transitions, but also factors that can hinder them. These are presented in chapter 4.1 as drivers and barriers. Since companies play a special role in the debate, they will be discussed separately. Chapter 4.2 aims to provide an overview of the learnings and possible recommendations from the literature review for the practical implementation of sustainability transitions. Throughout the research, niches have been shown to be particularly important, and it is interesting to look at them from the perspective of both incumbents and Start-ups, which will be discussed in section 4.3.

This chapter provides an answer to the second part of the research question about the ST research´s indications on practical implementation for businesses.

3.1 Drivers and Barriers of Sustainability Transitions

The drivers and barriers of sustainability transitions are divided into the following categories: environmental, social, political and institutional, technological and informational, economic and regulatory, and organizational. These categories are derived from the findings of the literature review and partly from additional, targeted research. To stay within the scope of this paper, they are summarized briefly, and it is important to consider that there are sector-specific variations in drivers and barriers.

3.1.1 Drivers of ST