Author: Theresa Marie Garrecht, May, 2025

1 Introduction

The financial services sector, as part of the financial sector, comprises financial entities dealing with the acquisition of financial goods. Due to the sector’s role in providing financial products and services and intermediating money between borrowers and savers, the sector significantly influences the allocation of financial flows.1 Redirecting financial flows to industries and projects indirectly impacts society and the environment. While the sector contributes to economic development and stability, it also supports industries that harm the environment or society; in other words, it contributes to and counteracts sustainability through its financial flows.2,3 In this work, sustainability or sustainable development is understood according to the Brundtland report from 1987 as development that fulfils the needs of current generations while ensuring that future generations can meet their needs.4 In order to protect the planet, its environment and people, and foster prosperity for all, the United Nations adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, including an action plan with 17 goals, known as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).5 The majority of funding for the SDGs is allocated at the national level through public resources, while the greatest potential lies in the private sector businesses, finance, and investment.6 Access to private savings has been particularly challenging, so that only a small share has been directed to sustainable development.7 The financial services sector has the potential to support sustainable development by providing sustainable finance and investment products and redirecting financial flows towards sustainability. In the past years, research in sustainable banking, finance and investment increased, particularly with the introduction of the SDGs and the Paris Agreement.8

This work assesses the financial services sector from a sustainability perspective, its impact on sustainable development, supportive strategies and measures, and drivers and barriers. It aims to provide a comprehensive overview of sustainability in financial services with the help of a non-systematic literature review. Chapter 2 presents the methodology, followed by Chapter 3 with a broad introduction to the financial services sector and sustainable finance and investment. In Chapter 4, the direct and indirect impact of the financial services sector on sustainability is assessed, followed by Chapter 5 on practical strategies and financial products and services for financial firms to contribute to sustainable development. Chapter 6 presents drivers and barriers that accelerate or inhibit the transition towards sustainable development. This work closes with a short conclusion.

2 Overview of the Financial and Financial Services Sectors and Sustainability Aspects Within the Sectors

This chapter provides a comprehensive overview of the financial sector and the financial services sector, also in the context of sustainability. The first section provides basic information, including the composition, activities and economic importance of the sector, supplemented by relevant key figures. The second section focuses on sustainability basics in the financial sector by presenting the basics relating to finance and investment in combination with sustainability, commonly labelled sustainable finance and investment (SFI). It also outlines the importance and size of the sub-sector around SFI.

2.1 Overview of the Financial Sector and the Financial Services Sector

The financial sector, as part of the services sector, comprises a wide range of institutions in the fields of banking, insurance, investment services and mixed financial holding companies.13 Table 1 gives an overview of the most relevant types of entities and their characteristics, such as financial institutions, financial firms or credit institutions. However, in the following course of this work, the focus will mostly be on financial entities in general. The sector is embedded in the financial system, which serves to allocate capital, monitor investments, manage risks, pool savings, and facilitate trade.14 By transferring money between savers and borrowers, the financial sector acts as an intermediary.1

Due to its functions, the financial sector is characterised by a high systemic relevance and a high dependency on trust, and it is therefore highly regulated. These aspects distinguish the sector from other, less capital-intensive sectors and give it a central role in economic development.15

Table 1: Types of Entities in the Financial Sector, Own table, see table content for sources.

| Type of Entity | Explanation |

| Financial Institution | A financial institution is a non-credit and non-insurance undertaking primarily engaged in acquiring holdings or |

| conducting other financial services like investment management, payment processing, and financial intermediation. This includes financial holding companies, mixed financial holding companies, payment institutions, and asset management firms.16 | |

| Financial Firm | A financial firms is a non-institutional entity that primarily engages in investment holding, acquiring monetary claims, leasing, proprietary trading, investment and corporate advisory services, and money brokerage.17 |

| Credit Institution | A credit institution is an undertaking engaged in accepting deposits or other repayable funds from the public and providing loans for its own account.16 |

| Investment Firm | An investment firm is a legal entity whose primary business involves providing investment services to third parties or carrying out investment activities on a professional basis.18 |

| Ancillary Services Undertaking | An ancillary services undertaking is a business primarily engaged in property ownership or management, data-processing services, or similar activities that support the main operations of one or more institutions.16 |

| Asset Management Company | An asset management company is a business that manages collective investment funds or provides similar investment management services, regardless of its location.13 |

| Mixed Financial Holding Company | A mixed financial holding company is a parent entity that, while not itself regulated, controls a financial conglomerate that includes at least one regulated entity.13 |

The financial services sector, as part of the financial sector, provides financing products concerning banking, credit, insurance, personal pension, investment or payment.19 Financial services refer to the acquisition of a financial good.1They are characterised by simultaneity, as the services are produced and consumed at the same time, and by intangibility, which also distinguishes them from other services. These two characteristics make them hard to evaluate before purchasing, requiring trust in the provider by the consumer.15 Moreover, financial services have a fiduciary responsibility, acting in the best interest of their clients. They depend on a two-way information flow, as providers and customers need to share and verify data to ensure the accuracy and benefit of financial decisions.20

Providers in the field of financial services trade, manage and take custody of financial instruments. Table 2 provides an overview of common financial services and their characteristics, as listed by the German Banking Act KWG. The underlying scope focuses on banking and investment and excludes insurance services, which also applies to the following work.

Table 2: Overview of Common Financial Services , Own table, based on the German Banking Act (KWG), as promulgated on 9 September 1998 (BGBl. I p. 2776).17

| Financial Service | Explanation |

| Investment Brokerage | The facilitation of transactions involving the purchase and sale of financial instruments |

| Contract Brokerage | The purchase and sale of financial instruments on the behalf of third parties for the account of third parties |

| Financial Portfolio Management | The administration of third-party assets invested in financial instruments, carried out with discretionary authority |

| Proprietary Trading | The process of buying and selling financial instruments for one’s account using equity capital, typically through quoting prices, executing client orders off-market, offering trading services, or using high-frequency algorithmic strategies. |

| Third-Country Deposit Brokerage | The arrangement or facilitation of deposit transactions with foreign-based companies. |

| Crypto Custody Business | The custody and administration of cryptographic instruments on behalf of others. |

| Foreign Currency Trading | The buying and selling of currencies to profit from exchange rate fluctuations. |

| Crypto Securities Register Management | Administration of a digital registry for electronic crypto assets. |

| Factoring | The continuous acquisition of receivables under framework agreements, either with or without recourse. |

| Finance Leasing | Execution of long-term lease arrangement as lessor and oversight of property companies not affiliated with an investment fund |

| Investment Management | Buying and selling financial instruments on behalf of a group of individual investors, where the product is designed to let them benefit from the performance of selected instruments, and they have discretionary input in the selection process. |

| Restricted Custody Business | The safekeeping and administration of securities solely on behalf of alternative investment funds. |

The financial services sector is dominated by banking and investment services. The banking sector is the backbone of the financial services sector, primarily focusing on facilitating savings and providing loans.21 Banking activities include the acceptance of deposits, the granting of loans, trading in financial instruments and the management of securities, as well as other financial services.17 Investment services, as another significant segment in the financial services sector, refer to the management, purchase and sale of financial assets.22

A financial asset is a legal claim on the income or wealth of a business, household, or government, typically represented by a document or digital record and often linked to lending activities.23 Financial assets can be distinguished into asset classes. However, there is no common understanding of the number and scope of different asset classes. Greer (1997) categorised investible assets into three super classes: capital assets, which generate income (e.g., stocks or real estate); consumable/transformable assets, which can be consumed or converted (e.g., oil or wheat); and store of value assets, which retain value over time (e.g., gold or art).24 Table 3 presents a list of capital asset classes.

Table 3: Overview of Capital Asset Classes , Own table, based on Hand et al. (2023).25

| Asset Class | Definition of Asset Class |

| Private Equity | A private investment into a company or fund in the form of an equity stake (not publicly traded stock) |

| Private Debt | Bonds and loans offered to a limited group of investors instead of being distributed widely through syndication |

| Real Assets | Investments in physical or tangible assets, like real estate or commodities |

| Public Debt | Bonds or loans that are traded publicly |

| Public Equity | Stocks or shares that are traded on public markets, also described as listed equities |

| Equity-Like Debt | Hybrid instruments combining features of both debt and equity, like convertible bonds or debt with profit-sharing options |

| Deposit and Cash Equivalents | Cash-focused investment strategies aimed at achieving a positive social or environmental impact |

| Other | Investments directed into outcome-based financial tools like social impact bonds or performance-based guarantees |

Within the financial services sector, a wide range of financial products exists. Financial products are contracts or packages of contracts that are typically offered by financial entities. Among the most popular retail financial products are bank accounts, credit cards, mortgages, personal loans, and investment products. Investment products bundle financial instruments, which are assets for exchange or trade.26 Table 4 summarises the most relevant financial instruments in the course of this work, which comprise equity and debt instruments and derivatives.

Table 4: Overview of Financial Instruments, Own table, based on Parameswaran (2022).22

| Financial Instrument | Explanation |

| Equity Instruments | Equity instruments represent ownership in a company and entitle shareholders to a share of the company’s profits through dividends and voting rights in major decisions. They are also known as ordinary shares and are typically traded on stock exchanges. |

| Debt Instruments | Debt instruments are financial claims that enable borrowers to raise funds by taking out loans with the promise to repay the capital together with interest at periodic intervals or a specific maturity date. Common examples are bonds, loans and promissory bills. |

| Derivatives | Derivatives are financial contracts that derive their value from an underlying asset or portfolio of assets. They grant certain rights or obligations to their holders based on the terms linked to the underlying market. The three major categories are forward and future contracts, option contract and swaps. |

Financial services contribute to the functioning of an economy. Intact financial systems mobilise and pool savings, produce information on potential investments, allocate capital efficiently and monitor investments. They manage risks and facilitate payments and the exchange of goods and services. These factors promote economic growth and job creation, generating resources for social spending and expanding access to financial services. Hence, financial sector development also contributes to the reduction of poverty. Particularly in developing countries, financial development accelerated through financial services contributes to economic growth.2 However, as some financial products allow speculation and lead to bubbles, the financial sector can harm economies by jeopardising financial stability, which in turn can harm economic stability.27

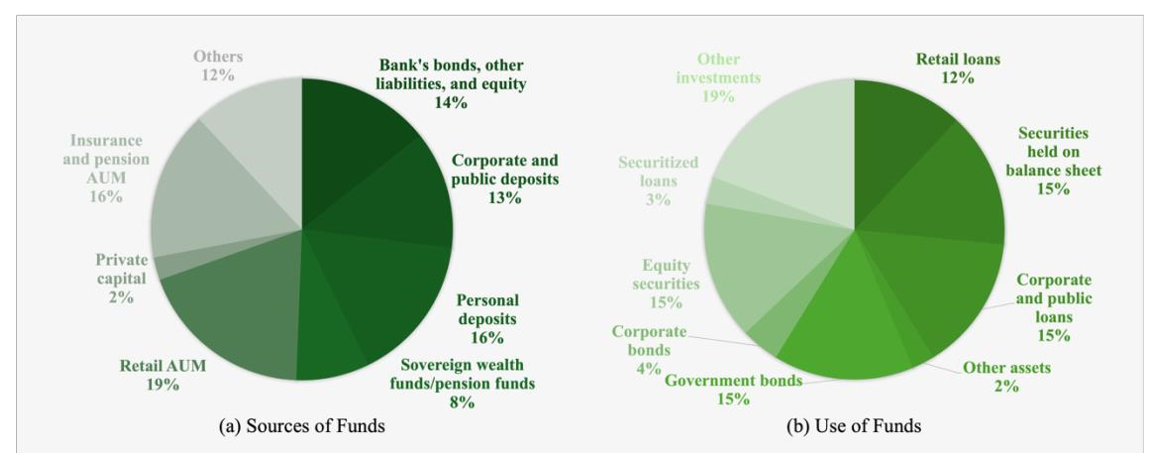

In 2023, the financial system intermediated United States dollars (USD) 410 trillion in assets globally. The most important sources of funding included personal deposits, bank liabilities, corporate and public deposits, and asset management, which are illustrated in Figure 1. The funds were used for various forms of investment, including private loans, corporate and public loans, government bonds, equities, and other investments. This resulted in a total revenue of USD 6.8 trillion in 2023, mainly through retail banking, corporate and commercial banking, wealth and asset management, and payment services. The global banking industry generated USD 1.15 trillion in net income in that year, which equals the combined net income of the energy and industrial industries.21

Figure 1: Financial Intermediation Globally in 2023,Own illustration, based on Mehta et al. (2024).21

Besides the volume of financial services, its relevance can also be shown by the amount of customers acquiring financial services. According to the World Bank, 74% of the world population over the age of 14 had a bank account in 2021, an increase of nearly 25% compared to 2011. While 96.4% of individuals in the high-income group had a bank account in 2021, only 23.9% of those in the low-income group did, indicating that financial services are primarily accessed by higher-income earners. However, in 2011, only 10% of low-income earners had a bank account, so more and more low-income earners have been added to the customer base of the financial services sector.28

2.2 Basics of Sustainable Finance and Investment (SFI)

Within the sphere of sustainable finance and investment, which are the broadest terms to describe financial aspects and investments that consider sustainability-related issues, many terms exist. There is neither a common definition of sustainable finance or sustainable investment, nor a common understanding of a concept.8,10,29,30 Before the 1970s, no specific terms in this context were commonly used, even though investors like churches considered ethical investments by restricting certain investments supporting businesses in the tobacco, gambling, or alcohol industries.31,32 The first attempts at describing sustainability-related terms in the context of finance and investment began in the 1970s under the influence of social movements with terms like socially responsible investment or ethical investment. In the 1990s, the ecological perspective was taken into account for the first time with the term green finance. From the 2000s/2010s, other terms were added, such as responsible investment, climate finance, ESG investment, as well as sustainable finance and sustainable investment.32 The terms mentioned above are described in detail in sections 3.2.1 and 3.2.2, while in this context, they underline the evolution and range of terms. Today, countries like China or the European Union (EU) frame sustainable finance according to their national taxonomies.29

Conducting a review, Cunha et al. (2021) investigated commonly used keywords and built a universal definition including the features of measurability, social and environmental aspects, as well as a long-term perspective. In their understanding, SFI refers to the management of financial means that focus on positive social and environmental impacts in the long term and that are measurable.32 They differ from the definition of conventional finance and investment in that they include ecological and social perspectives and take a cross-generational time perspective into account. This definition is consistent with the definition of sustainable finance by the International Capital Market Association (ICMA) from 2020, except that it also considers the stability of the financial system:

“Sustainable Finance incorporates climate, green and social finance while also adding wider considerations concerning the longer-term economic sustainability of the organisations that are being funded, as well as the role and stability of the overall financial system in which they operate.”33, p.5

The former definition by Cunha et al. (2021) is also consistent with other definitions of sustainable investment, e.g. the one by Eurosif (2022), where it is defined as “investments that have at least a low ambition to contribute to a sustainable transition.”34, p.7

While sustainable finance broadly encompasses activities in the field of sustainability and sustainable investment refers to a spectrum of sustainability-linked investment approaches, both terms serve as overarching terms, summarising a range of subcategories and terms.32 The next subchapters introduce and explain key terms and concepts under these two umbrella terms, providing a comprehensive overview.

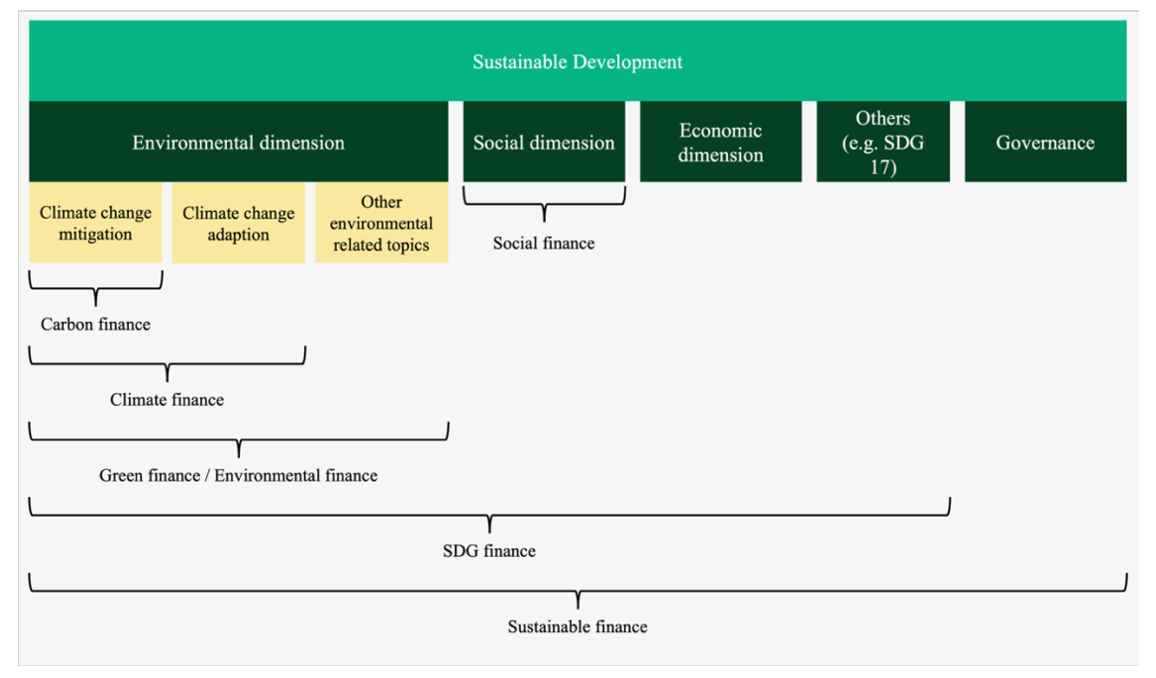

2.2.1 Basics of Sustainable Finance

In the context of sustainable finance, several commonly used terms have emerged. Terms like environmental finance, green finance, and SDG finance each refer to a specific dimension or subcategory within the broader field.12,32 The most common terms are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Clustering of Terms in the Context of Sustainable Finance, Modified illustration, based on Singhania et al. (2024).12

Table 5 shows the corresponding scope of the terms illustrated in Figure 2, in addition to other less common terms, such as blue finance, or terms that cannot be clearly assigned in Figure 2, such as microfinance. Another frequently used term in the context of sustainable finance, especially in the context of transition and green finance, is brown finance. It refers to financial flows that promote carbon-intensive projects, neglecting climate-related risks.35

Table 5: Overview of Terms in the Context of Sustainable Finance, Own table, based on Singhania et al. (2023) and Cunha et al. (2021).12,32

| Term | Scope |

| Blue finance | Blue finance aims to finance marine conservation.36 |

| Carbon finance / lowcarbon finance | Carbon finance or low-carbon finance targets financing in the field of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions mitigation, including mechanisms such as carbon credits and emissions trading.37,38 |

| Climate finance | Climate finance as part of green finance focuses on financial activities supporting climate change mitigation and adaption.39,40 |

| Environmental finance | Environmental finance covers financial matters that consider the planetary boundaries and environmental impacts in financial decision-making.41 |

| Green finance | Green finance focuses on financing for pollution reduction and GHG emissions reduction among other environmental benefits besides economic growth.42 |

| Microfinance | Microfinance describes the provision of financial services like microcredit, micro-insurance and micro-savings to people with low income, predominately in developing and transition countries with the aim to alleviate poverty though financial inclusion.43,44 |

| SDG finance | SDG finance aims to support the achievement of the SDGs by means of inclusive and SDG targeted finance.45 |

| Social finance | Social finance targets social issues such as social innovations or banking, microfinance and impact investing.46,47 |

| Transition finance | Transition finance is part of green finance and attempts to support the transition from carbon-intensive projects to green finance by managing physical and transition risks linked to climate change.35 |

Schoenmaker (2018) identified three approaches to sustainable finance that differ from traditional finance. Sustainable Finance 1.0 considers sustainability-related risks, focusing on maximum shareholder value in the short term. Sustainable Finance 2.0 deals with stakeholder value creation, optimising the integrated value of the environmental, social and financial value with a focus on the medium term. Sustainable Finance 3.0 aims at creating long-term value for the common good, prioritising social and environmental impacts over financial value.48

2.2.2 Basics of Sustainable Investment

To integrate sustainable finance, a spectrum of sustainable investment approaches exists. They vary in the degree of market force and deliberate impact on sustainable development and range from pure grants to investment opportunities yielding competitive returns, as illustrated in Figure 3. On one end is traditional or conventional investment, which is focused solely on financial gains, while philanthropy represents the other end.49,50 Traditional philanthropy refers to the voluntary commitment of individuals or organisations through donations or charitable activities to address social, cultural or environmental challenges. While traditional philanthropy focuses primarily on donations without direct influence, venture philanthropy, as a subsection, combines strategic investment and active management to maximise social impact.51 Within the remaining spectrum, some sources distinguish between impact investing, sustainable and responsible investment (SRI), and ESG investing, which are defined below.10,49,50 Other sources refer to SRI as the comprehensive term to describe a classification of subsequent approaches containing impact investing or ESG investing.52 Figure 3 gives an overview of the gradations of sustainable investment approaches. In the following, ESG investment, SRI, and impact investment are described in more detail.

Figure 3: Spectrum of Approaches for Sustainable Investment, Modified illustration, based on Singh (2020) and Swedroe & Adams (2022).49,50

ESG Investing

ESG investing refers to integrating environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors in an investment process, particularly during the investment analysis, aiming to optimise risk-adjusted returns. ESG investing is mainly connected to equity investment, although it can be applied to investment decision processes across asset classes. In comparison to SRI, ESG integration describes an approach of investment which focuses on riskreduction and optimal financial returns, regardless of positive impacts on sustainable development.53 However, there is no common process to integrate ESG factors into investment processes, as it refers to a wide range of strategies and practices.49,54 In practice, a wide range of techniques exists. Scenario analysis, sensitivity analysis, or benchmark-relative weighting are common techniques in asset allocation and portfolio construction. In equity security analysis, ESG investing can be applied by refining forecasted financial data, adjusting valuation model assumptions, and creating valuation multiples. In fixed-income analysis, it focuses on modifying financial forecasts and ratios, while also evaluating credit quality and credit spreads.53

Sustainable and Responsible Investment (SRI)

The term SRI stands for sustainable and responsible investment or less commonly for sustainable responsible investment or socially responsible investment and is used to refer to the use of positive and negative ESG criteria additional to financial criteria to achieve financial returns in investments, taking long-term sustainability aspects and risks into account.10,52,55 Unlike traditional investing, SRI considers ESG criteria to at least some extent to identify investments and risks.10 While some refer to ESG investing and SRI as synonyms not distinguishing the scope of intention, others differentiate the two by their focus on financial return.49,50 To those differentiating, ESG investing does not compromise financial profit at all, while SRI has a balanced focus on financial return and impact outcome.49Other sources refer to SRI as the comprehensive term to describe a classification of subsequent approaches as impact investing or sustainability-themed investing.52 Besides allocating financial flows by means of screening, SRI refers to shareholder advocacy and community investment.56,57 These instruments are further elaborated on in Chapter 5.2.1.

SRI intends to be built upon the six Principles of Responsible Investment, which offer guidance and a network for an investor base. According to the principles, SRI comprises the incorporation of ESG factors into the investment process, ownership policies and practices, the support of ESG disclosure of invested entities, the promotion of the effective implementation of the principles within the investment industry, and the reporting on SRI activities and progress.58

Impact Investing

Impact investing is closely related to SRI but extends the concept in terms of societal nonfinancial value creation by focusing on investments that strive for a positive environmental or social impact creation alongside a financial return.53,59 It is regarded as the most effective tool to finance the SDG investment gap.60 Originating from philanthropy10, financial capital is directed to people, communities, businesses or nongovernmental organisations (NGOs), that are often underserved by traditional finance.10,53 According to Weber (2018), the main characteristic of impact investing is that it is carried out off-market and therefore does not target listed companies, but instead focuses on specific projects, often with a small number of individuals.10 The definition by the International Finance Corporation (IFC), however emphasises the focus across classes. According to them, the decisive factor is not the affiliation to an asset class, but the investor’s intention to achieve a positive social or environmental impact.61 Hence, impact investing is characterised by its intentionality of impact creation, its use of evidence and data in investment design, its management of impact performance and its contribution to the growth of the industry.59

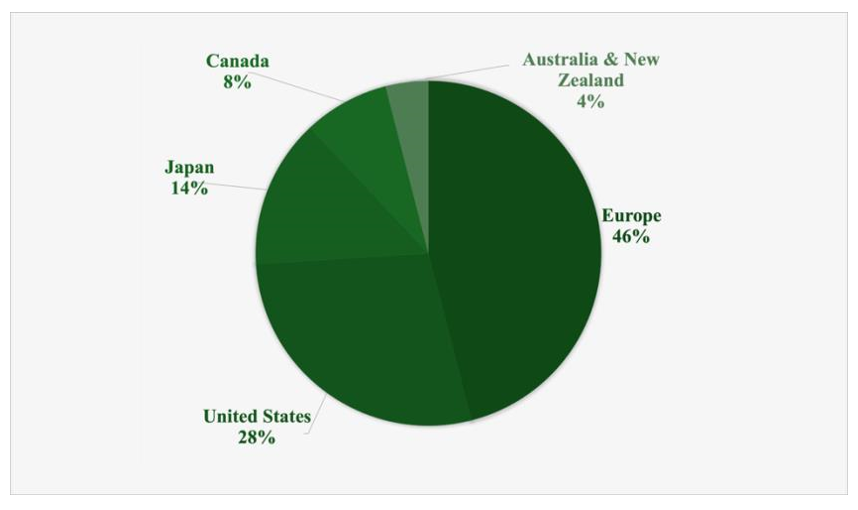

Figure 4: Share of Sustainable Investment Assets Across Regions in 2022, Source: Own illustration, based on Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (2023).62

According to the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (GSIA), in 2022, sustainable investment reached USD 30.3 trillion in assets across Australia, Canada, Europe, Japan, New Zealand and the United States, an increase of 20% in comparison to 2020. As displayed in Figure 4, almost half of the assets can be traced back to Europe and almost a third to the United States.62

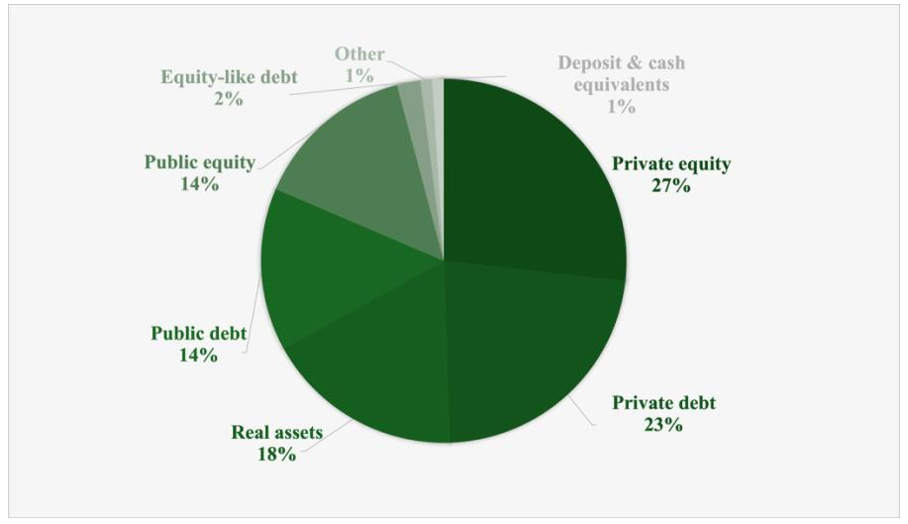

Taking an isolated look at impact investing, numbers by the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) show USD 1.571 trillion in impact investing under management by almost 4,000 organisations in 2024.63 In comparison to 2020, when USD 715 billion in assets were under management by around 1,700 organisations, this is a significant increase.64 The allocation across asset classes can be derived from Figure 5, with private equity as largest asset class for impact investing in terms of proportion of investors and proportion of assets under management (AUM) allocated to impact investing.25

Figure 5: Asset Allocation in Impact Investing Across Asset Classes in 2020, Own table, based on Hand et al. (2023).25

3 Sustainability Impact and Measurement

The following part assesses the impact of the financial sector on sustainable development, starting with the direct impact of banking operations, followed by the indirect impact, which can be attributed to the financial services through capital allocation. The second part explores measurement approaches to assess the sustainability performance of financial entities and the capital they allocate.

Jo et al. (2015) identified two perspectives on the sustainability-related impact of the financial sector. The first perspective focuses on the operational sustainability of financial entities, referred to as the direct impact. The second perspective examines the impact generated by the financial flows that pass through the financial sector, which can be described as indirect impact.65 In SFI, impacts are oftentimes assessed based on the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by the United Nations (UN), evaluating whether financial services and capital streams contribute positively, neutrally or negatively to sustainable development.10,12,66 In comparison to other sectors, the financial services sector has the highest rate of SDG reporting, underlining the relevance of the SDGs in this sector.67

In this chapter, positive and negative impacts are presented based on the SDGs. For this purpose, they are categorised according to the concept of the triple bottom line into the three pillars for sustainable development: ecological, social, and economic.68 Since many SDGs span multiple dimensions, such as SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) or SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), mainly referring to environmental and social aspects, various categorisations exist.69 This work categorises the SDGs in alignment with Schoenmaker (2017), except that it assigns SDG 11 to the ecological dimension, following the approach of Sardianou et al. (2021).69,70 Moreover, due to its relevance, SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) is listed under both the ecological and social dimensions. The classification used in this work is displayed in Table 6.

Table 6: Matching the SDGs with the Three Pillars of Sustainability, Own table, based on Schoenmaker (2017), Sardianou et al. (2021), Klapper, El-Zoghbi & Hess (2016) and United Nations (2015).5,69-71

| Pillar | UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) |

| Ecological | 7: Affordable and Clean Energy 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities 13: Climate Action 14: Life Below Water 15: Life On Land |

| Social | 1: No Poverty 2: Zero Hunger 3: Good Health and Well-Being 4: Quality Education 5: Gender Equity 6: Clean Water and Sanitation (7: Affordable and Clean Energy) 16: Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions |

| Economic | 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure 10: Reduced inequalities |

| 12: Responsible Consumption and Production | |

| Other/Overarching | 17: Partnerships for the Goals |

Regarding sustainability reports, financial entities mostly disclose information on SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), SDG 13 (Climate Action), SDG 4 (Quality Education), SDG 5 (Gender Equality), and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and

Infrastructure), covering the direct and indirect impact perspective. This aligns with other sectors, commonly disclosing SDGs 8, 9, and 13. Furthermore, from a sector-agnostic perspective, SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) are also relevant, although they are comparatively less reported on by the financial sector.67

3.1 Direct Impact

The direct impact of financial entities consists of impacts on the environment and society that are directly connected to the institution’s operations.72 Compared to industrial sectors with high resource usage and processing activities, the direct sustainability-related impact of the financial sector is relatively small.73 Financial entities put more emphasis on economic growth and good working conditions, as well as on governance aspects, such as the fight against corruption and financial crime, than on environmental concerns.69 Furthermore, direct impacts by the financial sector on social and human capital cover employee engagement, diversity and inclusion, customer privacy, data security, affordability, as well as selling practices and product labelling.72,74 Additionally, operational activities of banks have, such as those of other service-oriented sectors, an impact on climate change, land, water and natural resources due to energy, water and paper consumption, buildings, and employee travel.65,72 Nevertheless, the direct impact only represents a small fraction of the overall impact that is exerted by a financial entity. For example, in terms of CO2 equivalents (CO2-eq) emissions, those directly attributable to financial entities through their operations often make up less than 1% of the emissions associated with financial entities, while more than 99% are caused by financed projects.75,76

Table 7 summarises the relevant topics and displays common indicators disclosed by financial entities on their direct impact. In the following sub-chapters, these aspects are explained in more detail, starting with the environmental and social perspective. In addition, the governance perspective is assessed.

Table 7: Environmental, Social and Governance Issues for the Direct Operational Footprint of Financial Entities, Own table, based on Weber & Feltmate (2016), SASB (2018) and Commerzbank AG (2023).72,74,77

| Issues | Key Performance Indictors | |

| Environment | Operational emissions (if not divided according to the other environmental issues) | CO2-eq emissions |

| Paper consumption | Paper consumption in tonnes or in CO2-eq emissions | |

| Buildings | CO2-eq emissions from heating and energy use | |

| Employee travel | CO2-eq emissions from employee travel | |

| Electronic equipment | Electronic waste, energy efficiency of electronic equipment | |

| Solid waste management | Waste in tonnes or in CO2-eq | |

| Social | Employee engagement | Fluctuation |

| Diversity and inclusion | Gender pay gap, Proportion of gender, race and ethnicity | |

| Governance | Corruption, bribery issues, and financial crime | Confirmed incidents of corruption or bribery |

3.1.1 Environmental Perspective

Operations of financial services cause environmental impacts, such as operational emissions or other impacts due to energy consumption, telecommunication, paper consumption, electronic equipment, buildings, solid waste management, and employee business travel.72 These impacts are evaluated in the following. Given the limited literature on the ecological operational footprint of financial entities, the following section presents exemplary figures disclosed by Commerzbank AG, a commercial German bank recognised for its transparency in sustainability-related disclosures.78,79

Operational Emissions

Financial entities contribute to air emissions, even though they have significantly reduced their direct emissions over the last decades.80 These emissions are generally disclosed as CO2-eq of Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions.72 For Scope 1 emissions, Commerzbank AG refers to emissions directly caused by its operations, through heating oil or gas, for example. Scope 2 emissions represent emissions from purchased energy, which can be calculated using the market-based technique, considering the purchased energy mix, and the location-based techniques, using the statistical country mix. Scope 3 emissions of the operational footprint represent emissions caused along the value chain of the operations. They are disclosed separately from financed emissions.78 Financed emissions represent the emissions from an institution’s portfolio, e.g. through loans and investments. They are further explained in chapter 4.2.1. In general, Scope 3 operational emissions only make up a small share in relation to financed emissions.80 For Commerzbank AG, operational Scope 3 emissions are emissions caused by paper and water consumption, business travel and employee commuting.78 They are shown in Table 8.

Table 8: Operational Emissions Reported by Commerzbank AG in 2023, Own table, based on Commerzbank AG (2024).78

| Emission Category | Tonnes CO2-eq |

| Scope 1 | 17,418 (0.414 per employee) |

| Scope 2 location-based | 59,367 (1.410 per employee) |

| Scope 2 market-based | 12,867 (0.306 per employee) |

| Scope 3 | 46,306 (1.100 per employee) |

| Total (excluding Scope 2 location-based) | 76,591 (1.819 per employee) |

Paper Consumption

In literature and practice, direct environmental impacts in the financial sector are often linked to factors such as paper consumption.72,81 Resources such as wood and energy are used in the production, processing and disposal of paper. The origin of the raw materials can be particularly problematic, for example, if the wood is sourced from poorly managed forests or if social standards are disregarded during extraction. This can have a negative impact on the environment and society. Hence, paper consumption contributes to the depletion of resources, deforestation, air, water and land pollution.82 Financial players such as Commerzbank AG disclose their paper consumption, e.g. the total consumption in tons, consumption per employee or the CO2-eq emissions of paper consumption. In 2009, Commerzbank reported that around 1% of total operational GHG emissions were attributed to paper consumption, which indicates its low relevance.83 Still, in 2013, it accounted as one of the most relevant environmental indicators that Commerzbank disclosed with regard to its operational footprint.84 Between 2020 and 2022, the paper consumption of Commerzbank AG was between 2.623 and 3.646 t of CO2-eq per year, resulting in 0.083 to 0.110 t of CO2-eq per employee.77

Buildings

Buildings like bank branches, data centres or office buildings cause GHG emissions and contribute to resource, water and land use and solid waste generation.85 Regarding the environmental footprint of buildings, financial entities disclose relevant CO2-eq emissions. Scope 1 building emissions refer to polluting sources within the buildings, like furnaces, boilers and back-up diesel power generators. Scope 2 represents consumed purchased electricity, heat and steam. Scope 3 includes emissions associated with product or material usage and manufacture along the supply chain.65,72 Commerzbank AG disclosed the following information on electricity consumption and heating in its operations, as presented in Table 9. Fluctuations in the numbers can be attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic, among other things.77

Table 9: Energy Consumption Reported by Commerzbank AG from 2020 to 2022, Own table, based on Commerzbank AG (2023).77

| Energy consumption (in megawatt hours) | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

| Electricity | 169,529 | 151,534 | 131,944 |

| District heating | 49,972 | 74,271 | 44,654 |

| Natural gas | 97,755 | 61,670 | 68,802 |

| Heating oil | 2,299 | 2,767 | 1,532 |

| Diesel for back-up power | 246 | 311 | 407 |

Employee Business Travel

Business travel of employees contributes to Scope 1 emissions, which result from employees travelling with company-owned fleet, and Scope 3 emissions, referring to employee travel with other transportation modes, both contributing to climate change. Emissions from the travel industry account for 15 to 20% of global CO2 emissions.86 Due to crises, stabilisation efforts, and advancing digitalisation, the extent of business travel by banks has fluctuated multiple times in recent decades.72 Commerzbank AG published the following figures for 2020 to 2022, displayed in Table 10, though they also fall into the COVID-19 pandemic, where business-as-usual was restricted.77

Table 10: Emissions from Business Travel Reported by Commerzbank AG from 2020 to 2022, Own table, based on Commerzbank AG.77

| Emissions from business travel (in t CO2eq) | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

| Air travel | 951 | 369 | 8,159 |

| Rail travel | 79 | 77 | 150 |

| Road traffic | 3,870 | 2,143 | 4,468 |

| Other Emissions from business travel | 1,445 | 1,299 | 1,591 |

| Total | 6,345 | 3,888 | 14,368 |

Electronic Equipment

The use of IT equipment, which forms the basis for efficient operations in companies, particularly in service-oriented industries such as banks and financial entities, has become indispensable in today’s working world, contributing to environmental pollution and resource depletion.87,88 The manufacture of IT equipment, its energy consumption and increased productivity have a wide range of effects on the environment and society. Data centres require considerable amounts of energy for operation and cooling, which causes additional emissions. Hardware production requires resources and energy, while disposal generates waste and electronic scrap.88 As a service-oriented firm, Commerzbank AG relies on electronic equipment, which contributes to its environmental footprint. However, no specific data has been disclosed. Instead, the energy consumption of technical equipment is included within the Scope 2 emissions, as shown earlier in Table 8.77

Solid Waste Management

Like other firms, financial banks contribute to waste through the disposal of paper, outdated IT equipment, old furniture, and construction waste. The use and disposal of these resources contribute to environmental pollution and resource depletion.72 As part of its operational footprint, Commerzbank AG has published its amount of waste disposal, ranging from 201-241 tonnes CO2-eq between 2020 and 2022.77

3.1.2 Social Perspective

Financial entities are labour-intensive organisations and depend heavily on their workforce. By providing employment, skills development, and an inclusive corporate culture, banks play a crucial role in fostering economic and social well-being. These aspects can be attributed to several SDGs related to the social dimension, including decent work and economic growth (SDG 8), reduced inequalities (SDG 10), and gender equality (SDG 5). In terms of sustainability and financial materiality, banks further consider SDG 3 (Good Health & Well-Being) and 4 (Quality Education) as relevant, emphasising the importance of their workforce.69

Compared to other industries, financial entities report above average on SDGs 3, 4, 10 and 16. As employers, they report on their contribution to employability, upholding decent working conditions and learning opportunities, the implementation of occupational health and safety programs, and adherence to standards such as data privacy. These actions support several socially-focused SDGs, including ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being (SDG 3), quality education and lifelong learning opportunities (SDG 4), promoting decent work (SDG 8), and strengthening peaceful, just, and strong institutions (SDG 16).69 While Northern American and Western European focus on gender diversity when disclosing social sustainability information, East Asian, Latin American, Caribbean and Sub-Saharan African countries focus on employee engagement, such as learning initiatives.89 On the other hand, banks are being criticised for their compensation practices that contradict the principles of intragenerational equity, with chief executive officers and top management receiving multimillion-dollar salaries, while the banks suffered significant losses.72

Sustainability reports from banks frequently emphasise diversity and equal opportunity within their own workforce, which support SDGs 5 and 10. Moreover, unlike other social topics, diverse workforces in financial entities have been extensively researched by academia.72 For this reason, the following part assesses diversity in financial entities in more detail.

Diversity

Diversity plays a central role in banks’ social sustainability strategies, especially in terms of gender diversity.72 The Bloomberg Gender-Equality Index 2023, which analyses data from nearly 500 companies across 45 countries and various sectors, revealed that the financial sector lags behind the cross-industry average. Only 24.5% of management positions in the financial sector are held by women, compared to 38% in middle management and 30% in senior management roles across other industries.90,91 Looking at the board level, numbers from United States (U.S.) banks show that 30% of board members were female in 2018.92 In 2006, only 7% of board members in European banks were female. This issue is relevant because, according to a paper by Mateos de Cabo, Gimeno and Nieto (2012), which confirms the findings of former studies, women on boards take on a monitoring role, increasing overall risk management and sustainability performance.93 In light of the global gender pay gap of 17.6% in 2023 compared to 19% the year before, highlighting the income inequality between men and women in the financial sector, the gap has decreased slightly.90

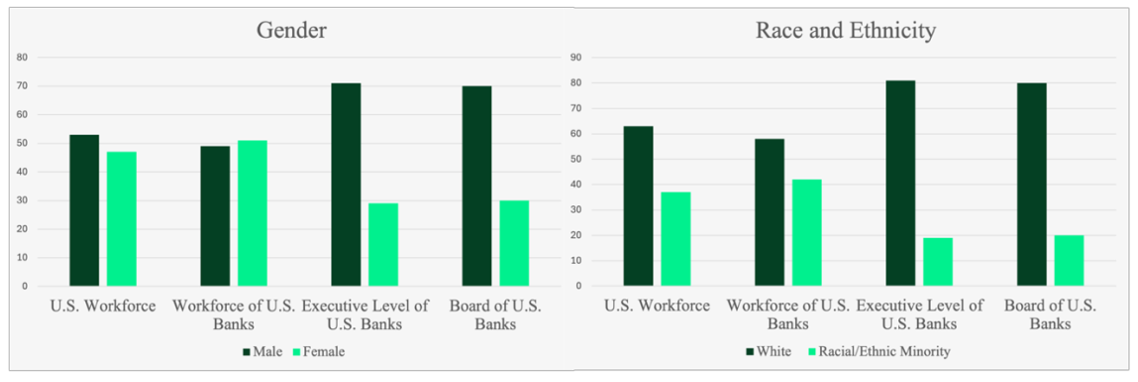

While the focus remains on gender studies, other diversity indicators such as age, education, experience, nationality and type of employment should also be taken into consideration when looking at diversity and equal opportunity.94The Committee on Financial Services of the US House of Representatives investigated diversity in terms of gender, ethnicity and race of the largest U.S. banks. The left side of Figure 6 compares the workforce of U.S. banks by gender to the overall gender composition of the U.S. labour force in 2018, indicating an unequal distribution at higher positions, with men dominating and a balanced distribution of men and women in the total distribution. The right side of the Figure 6 highlights that diversity in terms of race and ethnicity within U.S. banks is even lower.92

Figure 6: Gender, Race and Ethnicity of the U.S. Workforce and the U.S. Banking Sector in % in 2018, Own figure, based on U.S. House of Representatives (2020).92

3.1.3 Governance Perspective

Like other firms, financial entities impact the environment, society and economy by adopting responsible governance practices.72 While sound financial firms contribute to economic development by creating jobs, paying taxes and wages, investing in infrastructure such as commercial real estate for banking operations and fostering innovation, they can also harm financial stability. In the absence of adequate governance structures, banks endanger financial stability, which can have consequences for an entire economy. This was evident during the 2008 financial crisis, where large financial institutions were proven to be too big to fail, which also underlines their relevance.95 Since the cause was not only in the governance structure but also in the nature of the products and services, more information on the role of the financial sector in the crisis is shared in 4.2.3. Still, due to the focus on the short-term perspective and incentives, as well as high-risk behaviour, financial entities were key contributors to the crisis, as many institutions prioritised immediate gains over long-term sustainability.72

Furthermore, the management of corruption, bribery issues, and financial crime is among the most important aspects for banks in terms of ESG issues.69 High levels of corruption have a negative impact on bank stability, which in turn adversely affects economic stability and development.96 Bank corruption particularly affects small firms.97 Also, events of fraud have the greatest impact on financial entities’ reputation.98 Banks that do not implement corporate governance practices jeopardise financial stability, particularly in countries with higher levels of corruption.96

The importance of governance mechanisms can also be shown by corporate scandals, such as the 2020 Wirecard scandal. In 2020, the German provider of electronic payment processing services filed for insolvency after it was discovered that around USD 2 billion in cash was unaccounted for on its balance sheet, revealing one decade of organised fraud by top management. Institutional and private investors suffered major financial losses and lost confidence in the sector. This fraud was supported by inadequate governance structures, preventing internal supervisory mechanisms from working properly.99 As a result, while financial entities play a central role in economic development, their business models and governance structures can also pose significant risk.

3.2 Indirect Impact

The following sub-chapters present the indirect impact of the financial services sector, which describes the impact caused in the supply chain or by the clients, the ones providing or receiving financial resources.72 It can also be defined as the impact created through financial flows.65 Even though it accounts as the most relevant impact of banks, both negatively and positively, it is difficult to assess, as it has hardly definable system boundaries and for a long time, these kinds of impact were rarely disclosed by financial entities.72 According to Sabbaghi (2021), positive sustainability-related indirect impacts within one project, product or strategy arise when the impacts from a social and environmental perspective are greater than from an economic perspective.100 Though it is arguable to what extent the indirect impact can be attributed to the financial sector, and where it exceeds its scope. Nevertheless, great importance is attached to it due to the sector’s role as an intermediary of financial resources and its effects.72

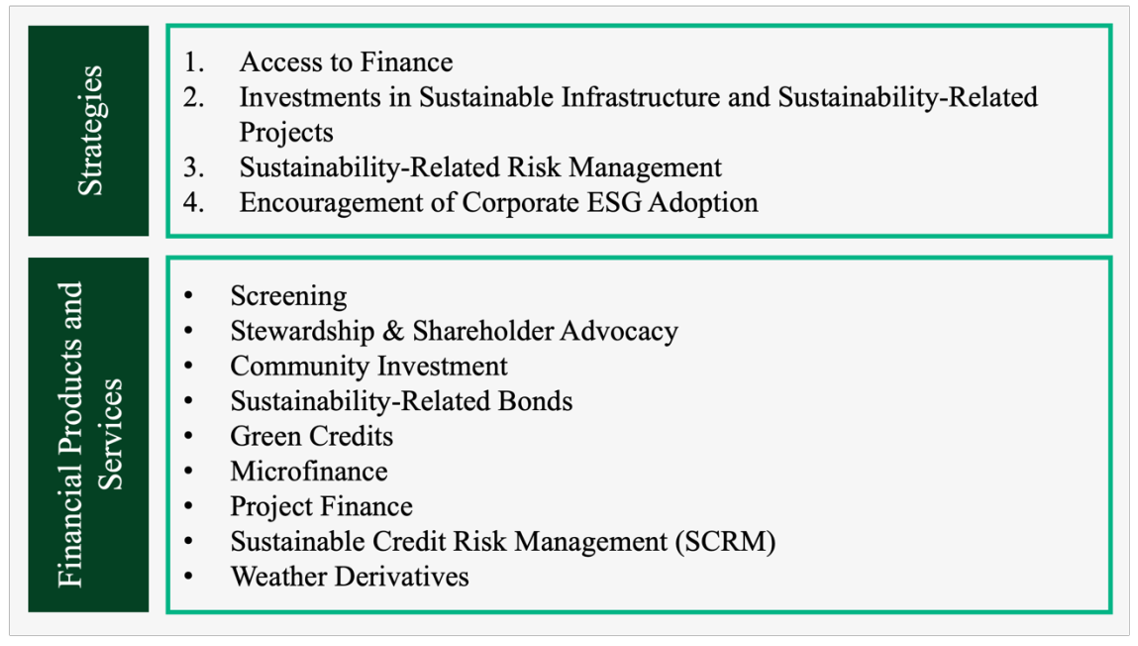

Overall, four areas in which financial flows create impact on society have been characterised in literature. Large parts of literature focus on indirect impacts created by granting or denying people access to financial products and services, namely financial inclusion. Indirect impacts are also created through investments either in infrastructure and projects hindering or contributing to sustainable development. Furthermore, impacts can be influenced by assessing sustainability-related risks and by encouraging firms to apply ESG criteria.101 In the following, those four areas are briefly described. These four fields can also be used as strategies to support sustainable development or its transition, so they are taken up again in chapter 5.1.

Access to Finance: Access to finance refers to the extent to which firms and individuals can directly access financial services.102 Since financial exclusion is associated with economic challenges and social exclusion, it is fundamental.15More concretely, access to finance is linked to the elimination of poverty (SDG 1) and hunger (SDG 2), better health (SDG 3), education (SDG 4), gender equality (SDG 5), access to clean water (SDG 6) and affordable energy (SDG 7) as well as economic impacts (SDGs 8 and 9), and reduced inequalities (SDG 10), which improves the individual’s life.103 According to a study by Yap, Lee & Liew (2023), financial inclusion correlates particularly positively with the financially-focused SDGs 2, 5, and 8, while for SDGs 1, 3, 9, and 10, the correlation was less significant. Unlike the earlier study, this paper did not include SDGs 6 and 7 in the analysis regarding financial inclusion.104 Financial services can also constrain or counteract the achievement of several SDGs by denying access to financial services. This happens when individuals have insufficient income and are not considered bankable, which poses risks to lending for financial entities. Involuntary financial exclusion also occurs under discrimination, particularly through insufficient contract or product features, inadequate informational frameworks, and pricing.102 Individuals with lower income and wealth, women in emerging markets, as well as ethnic minorities, people of colour or with disabilities and immigrants are more likely to be excluded from financial services.103

Investments in Sustainable Infrastructure and Projects: Financial services play a role in financing essential infrastructure, such as roads and energy, as well as other projects, such as those related to climate protection, contributing to economic and social development and to mitigating environmental pollution. These investments are primarily linked to water and sanitation (SDGs 6), energy (SDG 7), industry, innovation and infrastructure (SDG 9), and climate action (SDG 13), although other SDGs are influenced by financing projects as well.101 While investments have enhanced social welfare and economic development, a large part of historical investments also contributed to the acceleration of climate change and environmental destruction. This indicates the role of financial services in supporting and constraining or counteracting the achievement of sustainable development and the SDGs.3

Sustainability-related Risks: The financial services sector can enhance sustainable development and address sustainability-related challenges by managing sustainabilityrelated risks. By leveraging its capacity as a risk manager by effectively identifying, assessing and managing such risks, they contribute to a more resilient economic system, thereby particularly addressing responsible consumption and production (SDG 12).101

Encouragement of ESG Practices: Acting as an intermediary between capital providers and the real economy, the financial sector has an influence on the ESG practices of its corporate clients. It can shape corporate behaviour and encourage the adoption of sustainable business models. This, in turn, can enhance several, if not all, SDGs, but particularly climate action (SDG 13), marine and terrestrial ecosystems (SDGs 14 and

15), and peace, justice and strong institutions (SDG 16).101

Unlike the first 16 SDGs, for which the impact is explained in the following, SDG 17, Partnerships for the Goals, plays an overarching role in achieving sustainable development, with the role of the financial sector to provide additional financial resources.5,10 In order to reach the SDGs by 2030, USD four trillions are needed annually, with a growing share required to be directed to developing countries.105 The role of the financial sector is central to financing the gap, as domestic governments only provide 50 to 80% of the funding.106 By forging partnerships, e.g. between companies, financial entities and NGOs, the other goals can also be advanced.101 A large part of banks already enhance SDG 17 by entering partnerships with global financial technology, startups, global institutions, climate experts and organisations to influence policies and regulations and promote sustainability.89

The following part assesses actual and potential positive and negative indirect impacts from an environmental, social and economic perspective. Since in academia and in reports by financial entities, indirect impacts are commonly disclosed and assessed based on the SDGs, the following part assesses the impact per SDG, allocated to the environmental (7 & 11, 13-15), social (1- 7 & 16) and economic (8-10 & 12) dimension.69 A list of the SDGs and their corresponding topics was provided earlier in Table 6.

3.2.1 Environmental Perspective

Financial services contribute indirectly to climate change, its mitigation and adaptation, pollution, and other environmental aspects through intermediating financial flows. Adaptation efforts by global banks include governance structures, climate-finance initiatives, and risk models to identify climate risks and opportunities, while mitigation focuses on measuring emissions, restricting high-emission financing, and supporting green investments, even though these objectives sometimes conflict.80 Taking in their perspective, banks identified SDGs 7, 11 and 13 as most relevant in terms of environmental SDGs for their business and impact.69 However, positive and negative impacts associated with the financial sector appear for all environmentally targeted SDGs (SDGs 7, 11, 13, 14 and 15), which is shown in the following.

SDG 7 – Affordable and Clean Energy

The International Energy Agency estimates that USD 1 trillion needs to be raised annually for the transition to a low-carbon economy by 2050, showing the potential of the financial sector to support these efforts, contributing to SDG 7. Financial entities are raising investment for low-carbon transitions by developing portfolios, including carbon markets and renewable energy projects, applying financial expertise to energy pricing for universal access, underwriting large-scale renewable projects, and promoting responsible investment practice.107

Green financing plays a crucial role in promoting sustainable energy projects, but despite growing investment, fossil fuel financing remains dominant on a global scale, which is shown in the section on SDG 13. From 2008 to 2021, the Global Bank issued over USD 16.4 billion in Green Bonds, 63% of which were designed for renewable energy projects, energy efficiency, and low-carbon transportation. The funding was used for the construction of hydroelectric and geothermal power plants, among others.108 Xiong & Dai (2023) examined the impact of green finance on SDG 7 in China and showed that investment in sustainable energy promotes sustainable development by influencing the energy use structure, reducing pollution and promoting innovation. The authors showed that this influence was particularly evident in economically more developed regions, while the potential remained untapped in less developed areas.109 In 2022, international public financial flows for clean energy in developing countries rose by 25% to USD 15.4 billion, though still significantly below the 2016 peak of USD 28.5 billion.110 At the same time, financing fossil fuel remains significant, which is also discussed in the part on SDG 13.80,111 Beltran & Uysal (2023) looked at 60 financial entities that invested between USD 600 and 800 billion annually from 2016 to 2021 in fossil fuel production. Around threequarters was funded by 27 of the 60 firms alone.80

SDG 11 – Sustainable Cities and Communities

Financial services contribute to SDG 11 by enhancing urban resilience and safety through collaboration, data sharing, and education. This is done, for example, by evaluating the resilience of transport infrastructure with different stakeholders or by offering education about weather-resilient building materials and techniques, as financial entities manage risks and account for climate-related physical and transition risks.101 Finance Norway conducted a study on leveraging disaster loss insurance data to help municipalities prevent climate-related hazards and urban flooding. Funded as a public-private partnership, the project shared geo-coded data with universities and municipalities for improved spatial and land-use planning. Initial results indicated that this kind of data sharing enhances disaster resilience.112

SDG 13 – Climate Action

Financial entities contribute to combating climate change and its impacts by financing climate mitigation and adaptation. This includes issuing green bonds, integrating climaterelated risks into underwriting practices, investment analysis and decision making, divestment or exclusion in case of non-alignment with ESG practices, and publicly disclosing the carbon footprint of portfolio investments.72,101 Regarding indirect emissions in the financial services sector, financial entities have been increasing the share of green finance, lowering financed emissions. The year 2022 marked the first time that developed countries mobilised USD 100 billion for climate finance, which they committed to do annually from 2020 to 2025. This represents an increase of 30% compared to 2021. 60% of that sum was allocated to mitigating and 40% to adapting to climate change.110

Still, financing fossil fuel and other emissions remains significant.80 According to the SDG report 2020, in 2016, climate finance was USD 681 billion, lower than finance in fossil fuel with USD 781 billion.111 A study by Manych et. al. (2021) compared territorial and financed emissions by commercial banks from coal power plants that were commissioned after 2014 and found that except for China, which financed approximately the same amount of emissions as it produced, the U.S., some European countries and Japan financed more emissions than they produced, due to emissions financed abroad. In contrast, countries like Vietnam, Indonesia or partly India produced emissions within their countries that were financed by foreign countries.113 This aligns with a study by Greenpeace in collaboration with WWF, stating that, in 2019, the financial sector of the United Kingdom was associated with 805 million tonnes of CO2-eq, which was 1.8 times the territorial emissions.114 However, given the various methods used to assess financed emissions and the challenges in quantifying them, figures on financed emissions need to be considered with caution.115

On the other hand, between 2014 and 2018, the proportion of loans granted by European banks to polluting companies fell by around three percentage points compared to less polluting companies, following the announcement of the Paris Agreement in 2015.116 Moreover, some of the globally systemically most important banks announced that they will direct USD 9 trillion to sustainable financing for low-emission and social causes by 2030. However, of the 30 banks that did commit to achieve net-zero by 2050, only eight measured Scope 3 emissions to at least some extent, underwriting a misalignment between committing and taking actions. From those partially measuring Scope 3 emissions, many only measured Scope 3 emissions from business travel, excluding financed emissions, while others only measured financed emissions for some sectors.80

SDG 14 – Life Below Water

Even though SDG 14 belongs to the least mentioned goals in connection with the financial services sector, the sector can contribute through guidelines, policies and rating systems to enhance SFI mechanisms and prohibit polluting investments in order to conserve water and maritime resources and their sustainable use, engaging in blue finance.36,100,101 Standard Chartered has established a Fisheries Position Statement that guides its debt, equity, and advisory services. It sets good practice principles and standards to assess clients’ ability to manage environmental and social risks. The bank also outlines exclusionary practices, prohibiting engagement with companies involved in drift net fishing and deep-sea bottom trawling.117

SDG 15 – Life on Land

Financial services can both hinder and support life on land by contributing to its destruction or promoting the sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems and forests. By raising capital, applying criteria to investments in certain sectors and valuing ecosystem services, negative impacts are prevented.10,72 Several large banks, covering 50% of global trade finance, have adopted the Banking Environment Initiative’s ‘Soft Commodities’

Compact, aligning with the Consumer Goods Forum’s goal of zero net deforestation by 2020. This collaboration led to the creation of the Sustainable Shipment Letter of Credit, a trade finance product that lowers the cost of importing sustainably certified palm oil into emerging markets and aims to prevent deforestation. Moreover, some banks have adopted policies for forestry, forest products, agriculture and fisheries, among others.118 For instance, Standard Chartered has a position statement on sustainable agricultural practices, denying financial services to the biofuels industry, growing their crops in highwater stress areas.119 On the other hand, as of 2021, less than half of the 150 most destructive financial entities in terms of tropical deforestation have deforestation policies. Furthermore, only one-fifth of existing deforestation policies cover all four risk commodities: palm oil, soy, timber and cattle products.120

3.2.2 Social Perspective

The financial sector has a significant impact on the social sphere of sustainability, particularly in poverty reduction and improved living standards through access to financial services.27,71 Besides poverty reduction (SDG 1), the impacts of inclusive finance support the achievement of other SDGs, such as SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) or SDG 5 (Gender

Equality).71,104 Less discussed in literature but still of relevance in light of the social sphere are indirect impacts on SDGs 3 (Good Health and Well-Being), SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation), SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) as they are part of essential infrastructure, and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions).104

Social impact creation is often connected to microfinance and financial technology (FinTech), as they enable opportunities for inclusive finance.44,71 In 2023, the estimated total market size of microfinance was USD 195.3 billion by gross loan portfolio, with an increase of 10% compared to 2022. Furthermore, 142 million individuals received microloans that year. The median of the average loan balance as a proportion of gross national income per capita improved to 44.6% due to microfinance, compared to 43.7% in 2022.121

On the other hand, progress on sub-goals particularly addressing inclusive finance lags behind, inefficiencies prevent the achievement of progress on the SDGs, and certain activities counteract their achievement, such as conflicts or wars are being financed, increasing humanitarian costs. Moreover, financial development has been linked to increased inequality and discrimination.122,123 The following part assesses these impacts in more detail by presenting supporting and counteracting activities in relation to the SDGs.

SDG 1 – No Poverty

In academia, a large field of research deals with the link between financial inclusion and poverty reduction, mainly through enhancing access to financial services through basic financial services or microfinance.27,71 As sub-goal 1.4 of SDG 1 calls for improved access to basic services, such as financial services, to all men and women by 2030, and evidence suggests that economies with developed financial systems can eradicate poverty on a larger scale, the role of financial services in poverty reduction becomes clear.5,102 The Global Impact Investing Network analysed the progress towards SDG 1.4. It showed that as of 2022, for South Asia, Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, the percentage increase in clients that actively use financial services outperformed the necessary threshold needed to achieve SDG 1.4 by 2030. For Latin America and the Caribbean, however, the threshold was not achieved.122

The multinational development bank World Bank has aligned its mission to end extreme poverty with most of its projects, contributing to SDG 1.100 In Central America, the World Bank supported a social protection project, which enabled Honduras to set up a program for conditional cash transfers and a social register for targeted poverty reduction. Through this program, 234,000 extremely poor households in rural areas received financial support.124Further examples with a focus on other social SDGs, which are presented in the following, also contribute to poverty reduction.

SDG 2 – Zero Hunger

Besides providing financing and payment products to smallholder farmers, investments in sustainable agriculture contribute to progress towards SDG 2 to end hunger. As the development of sustainable agriculture is central to combat hunger, and access to financial services for small-scale farmers leads to better yields, improving stable food supply worldwide, access to finance has a significant impact on SDG 2.104 A study by Brune et al. (2015) came to the result that Malawian cash crop farmers with a savings account increased investments by 13%, which resulted in increased crop yields by 21%.125 Moreover, the provision of short-term credits to farmers in Zambia increased the revenue by an additional yield output of 10%.126 Improved access to finance for farmers is also achieved through the application of FinTech, as farmers often live in rural areas and would have additional travel costs when travelling to banks to acquire financial products.127 For instance, by connecting financial entities with customers, the World Food Programme, in partnership with MasterCard, has been able to finance 150 million school meals around the world since 2012.128 Furthermore, banks link investments to conditions regarding sustainable development. For example, Standard Chartered reported that it allocated capital to key economic sectors, including agriculture, financing USD 31 billion through its Commodity Traders and Agribusiness portfolio in 2014, while enforcing agribusiness standards to assess clients’ social and environmental risk management and restricting services to those failing to meet certain standards or guidelines.119

SDG 3 – Good Health and Well-Being

By raising or providing capital for investment in the healthcare sector, financial services contribute to SDG 3, ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being. Additionally, financial inclusion contributes to better health, as increased healthcare coverage leads to better accessibility to medical services.71 However, evidence suggests that there is only a weak correlation between financial inclusion and improved health.104 There is a variety of financial instruments applicable for healthcare, which support the financing gap of SDG 3, particularly through impact investing, pooled investment funds, and different kinds of bonds.129

SDG 4 – Quality Education

Innovative finance approaches such as education bonds or other forms of investment in education, as well as access to savings and loan products and financial literacy, contribute to quality education and learning opportunities for all, as a lack of education in countries where private education dominates is often linked to financial barriers. In sub-Saharan Africa, for instance, a third of pre-primary students attend private institutions, putting children from the poorest households at a disadvantage.110 The Inter-American Development Bank issued a USD 500 million Education, Youth and Employment Bond for Latin America and the Caribbean to finance early childhood care, primary and secondary education, and vocational training, with proceeds placed in a segregated subaccount for projects focused solely on education and youth employment. From 2023 to 2027, the programme expects to benefit over 2.5 million students and approximately 100,000 children, and provide employment for 46,000 people.130

Access to savings accounts increases spending on education, as shown by a study in Nepal, where spending on education increased by 20% after households had opened a free bank account.131 Researchers introduced a remittance product for Salvadoran migrants in the U.S., allowing them to send money directly for students’ education in El Salvador, with matching funds provided. This led to higher educational spending, increased private school attendance, and lowered dropout rates. Additionally, for every dollar received in remittances, students invested nearly four dollars of their own money in education.132

The impact on SDG 4 is also connected to enhancing financial literacy, which means the ability of individuals to make informed decisions about financial issues like saving, investing, and borrowing. In 2014, the World Bank estimated that only 33% of adults worldwide were financially literate, including 38% of those with bank accounts. Among account holders, financial literacy rates stood at 57% in major advanced economies and 30% in major emerging economies.133

SDG 5 – Gender Equality

By adapting credit processes and designing inclusive financial products, financial entities have successfully reached out to women, providing them with access to services from which they were previously excluded or disadvantaged.101,134 Providing women with access to financial resources improves their power in decision-making, traditional gender expectations are slowly dissolved, and women have better opportunities to participate in modern society.104 Particularly through microfinance, women have been impacted over the last decades.135 By lending to women, women gain decision-making power in their families, access to society, to information or training, which can reduce their vulnerability. Moreover, women have the choice to use contraceptives as they depend less on having children as life insurance, infant mortality is decreased, and children of women with access to credit are more likely to go to school.134

However, the impact of microfinance is controversial, as some doubt its effectiveness.135,136 For example, domestic violence decreased in some cases due to access to financial services, as, as women were participating more frequently in social events and therefore moved closer to the centre of society. In other cases, domestic violence increased as tensions between husband and wife increased. Sometimes, women were forced to give up their loaned funds to their husbands, leaving the women unable to pay off their loans and fulfil their financial obligations.134,135 From the 142 million individuals reached by the end of 2023 through microfinance, around 60% were female.121

SDG 6 – Clean Water and Sanitation

Even though the literature on the impact of financial services on SDG 6 is scarce, there has been evidence that innovative payment products can enhance access to clean water and sanitation. Since many households in developing countries lack access to essential infrastructure, such as clean water and sanitation, financial services can contribute to better access through innovative financial products. With the help of pay-as-you-go (PAYGO), which refers to services that are triggered automatically the moment the payment is received, access to clean water services can be improved among low-income individuals, as payments are directly linked to usage. Customers pay via smartphone for the volume or time purchased. Besides the benefits for users, businesses offering the services increase revenue, as more customers actually pay the costs for water and more customers can be reached. However, this FinTech solution also presents shortcomings in social development, as it can lead to job losses at local water providers and make water access more expensive due to additional fees.137

SDG 7 – Affordable and Clean Energy

SDG 7 also refers to social issues, as energy is part of essential infrastructure, and improved access contributes to the achievement of many other socially focused SDGs.71 Similar to water utility, access to energy can be improved through PAYGO systems. PAYGO models for energy supply are available in over 30 countries, offering off-grid energy services through recurring payments. Companies operating in Kenya, Tanzania, Namibia, Ghana, Somaliland, and Peru have created portable solar lights that off-grid consumers can purchase over 3 to 12 months using mobile payment services and PAYGO pricing.138

SDG 16 – Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

Financial entities are working with global stakeholders like the World Bank and Financial Stability Board to enhance transparency and security in financial flows, e.g. by leveraging financial technologies. They promote responsible business conduct in high-risk areas by linking capital access to ethical practices and engaging with local communities to understand risks. Additionally, they support social enterprises and impact investments, particularly in post-conflict regions, ensuring that marginalised groups are included. Through data-sharing to combat crime, offering financial products for victims of violence, or ensuring that indigenous rights are respected in financing decisions, financial entities contribute to SDG 16.101 For instance, in 2014, MasterCard, in collaboration with the Nigerian government, launched a biometric National electronic ID Card with integrated electronic payment services. The initiative aimed to provide financial services to over 100 million people, enhancing accessibility and inclusion. However, the program was stopped in 2019 due to concerns over illegal competition and violation of data protection.139

On the other hand, there is a linkage between the financial sector and conflict issues, as the financial sector plays a role in generating narrow development that intensifies existing tensions or creates new ones and in financing conflicts, such as wars. When financial systems fail to alleviate poverty and inequality, conflicts can emerge, often influenced by financial resources. During conflicts, both domestic and foreign finance play a role in determining the duration and outcome, affecting humanitarian costs. In post-conflict situations, rebuilding the financial system is essential for social well-being and economic recovery, as it encourages private investment and enables public spending on reconstruction. Additionally, currency reforms in conflict-affected countries are challenging due to weak institutions. Ultimately, strong financial regulation and supervision, supported by democratisation, are essential to prevent financial systems from fuelling instability.123

3.2.3 Economic Perspective

Financial products and services serve as both a key driver of sustainable economic development and a potential source of risk and economic instability, contributing to and constraining or counteracting several economically focused SDGs, such as SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure),

SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production).