Authors: Fokko Folkerts, Mathis Stricker, Tobias von Nethen, August 31, 2024

1 Definition

Peace and Justice are fragile while many reasons can cause disturbance which most likely leads to suffering humans and nature. The number of conflicts in the world is difficult to count, the Geneva Institute of International Humanitarian Law provides an overview of armed international and non-international conflicts, that states over 110 ongoing armed conflicts with uncertain but high figures in the Middle East and Africa.1 At the end of 2023 the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) finds 117.3 million people worldwide who have been displaced by force.2 The ongoing conflicts have a direct influence on civil life by destruction of infrastructure and attacks on densely populated areas for example through Russian bombings in Ukraine.3

A case of countrywide intense discrimination of women and girls is currently taking place in Afghanistan under the new Taliban regime which excludes them from most of public living.4 A symptom of manmade environmental damage is the deforestation especially in fragile biospheres of tropic rainforests, where deforestation declined in 2023 compared to 2022 while global deforestation increased by 3.2%.5 Deforestation accelerates climate change that is an emerging reason for migration as it endangers human needs in affected areas.6 Reasons like these in places all around the globe fuel the suffering of humans that may hold on for generations if nothing is done against it, here thoughtful sustainable business practices can contribute to the wellbeing of people and improve peace and justice in the world.

1.1 Peace

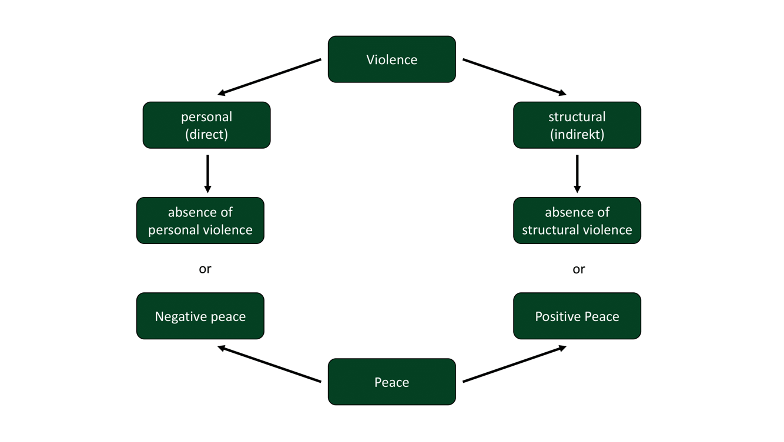

One of the fundamental definitions of the concept of peace today comes from Johan Galtung. His distinction between positive and negative peace describes the absence of personal or structural violence. Personal or direct violence is characterized by the immediate goal of intentionally harming third parties, as in wars. Structural violence refers to various aspects of violence that result from systemic structures.7 These may not be intentional, but can have deadly consequences for individuals, such as hunger and disease.8 The conditions of structural violence can be broadly defined as social injustice.9

Galtung distinguishes between positive and negative peace, since the absence of personal violence does not necessarily lead to a positive state. The absence of structural violence, on the other hand, represents, as described above, a state of social justice, which is a positively defined state that describes the egalitarian distribution of power and resources.7

One criticism of this approach is the use of the terms “positive” and “negative”. It could be related to the fact that the achievement of peace could be good (positive) on the one hand, but also bad (negative) on the other. Potential peace work could be impaired by this evaluation.10 Another point of criticism is the conceptual vagueness of the positive concept of peace.11

However, it is undisputed that peace is more than just a state. Rather, in modern literature, peace is understood as a complex process in which the reduction of violence on the one hand and the increase of justice on the other are defined as central goals.11

1.2 Justice

Defining justice in a timeless and universally applicable way is at least close to impossible and a complex philosophical topic with multiple questions to debate about. First conceptions were made by Greek philosophers like Aristotle and Plato, who at their time saw justice as a virtue in action, and a moral obligation that has to be met by a member of a community. Aristotle invented a model of two kinds of justice that roots in the slogan ‘to treat equals equally’.12 The first way of his definition is the ‘distributive justice’, which concerns the distribution of common goods within a community depending on certain criteria that define one’s share. The other one, rectificatory or commutative justice, focusses on fairness in trades, and every party to receive a satisfying outcome. This conception can also be applied to compensation for damages, while in both cases every party shall gain at least what they give.13

However, until today the conception has developed into a wide field of justice forms in major and minor categories. For this field of strategic management there are more than just one useful theory. Setting the focus on Supply Chain Management, the justice theory for supply chain collaboration is part of the organizational justice, which we only partly cover in this article. The theory divides the inter-organizational interaction between supply chain partners in three justice-related sections, (a) the distributive justice, (b) procedural justice, and (c) interactional justice.

- Distributive justice in this case is related to Aristotle’s approach of rectificatory justice. It focusses on the compensation which can be influenced by equality of partners, situations of need as well as organizational goals and motives. Fairness in this field can be found when all partners consider the trades as beneficial for their operations.14 Here can be distinguished between equity-based distributive justice where outcome-to-input ratios have to be equal, equality-based distributive justice comparing the different outputs regardless of inputs, and need-based distributive justice only looking at the own known needs neglecting the inputs.15

- Procedural justice focusses on the process part of business relationships. It includes the perceived fairness within the procedure of negotiations, legal affairs, handling of payments, and reliability. Partners should be allowed to express their opinions and ideas on a formal basis.15

- Interactional justice is the perception of social interaction between the acting parties. Respect and a well-maintained personal relationship count towards the subcategory of interpersonal justice which is complemented by informational justice which consists of flawlessly functioning information exchange and provision of explanations are part of this form of justice.16

2 Analysis

The number of global conflicts is difficult to measure. While the Geneva Institute of International Humanitarian Law counts over 110 armed conflicts,1 the Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research (HIIK) mentions 363 global political conflicts, with 216 of them involving violence.17 Multinational corporations (MNCs) frequently conduct business in these specific regions where the governments are incapable or unwilling to protect even the most fundamental human rights of their own citizens.18 These companies face complex challenges in such environments due to the lack of state governance and the need to navigate conflicts while upholding human rights standards.19

At the same time, however, conflicts are exacerbated by corporate activities.20 The extractive sector can be cited as an example of this. It has been accused of financing war and violence on the ground through its trade in valuable commodities, such as diamonds from Sierra Leone.21 The oil company Shell has been accused of collaborating with the Nigerian government to repress Ogoni activists in the 1990s so as not to disrupt oil production.22 These are just two of many examples of companies having a negative impact on the situation in politically troubled areas.

There is an academic discourse on how to prevent these problems. Current research is investigating the extent to which companies can contribute to the creation of peace and justice.23 The topic is also of great political interest. In 2013, the United Nations Global Compact published the Business for Peace (B4P) initiative.24 This initiative assigns the private sector an important role in peacebuilding in crisis regions.25 In recent years, the private sector has been encouraged by governments, organizations and international non-governmental organizations to fight poverty and promote socio-economic benefits, among other things. There is a belief that the help of the private sector is necessary to build peace in these regions.26

Another approach that underscores this are the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which seek to end the world’s worst injustices and establish a peaceful world as well as radically alter global society.26 The promotion of peace and justice is thereby reflected in SDG 16.27

2.1 Measuring peace

Before companies can make a positive contribution to peace and justice, it is first necessary to define what political conflicts are and how peace can be measured. It also presents SDG 16 indictors that companies can use to measure and benchmark their performance.

The HIIK describes political conflicts as contradictory goals between individual or collective actors. This contradiction manifests itself in actions and communications related to important social issues or threats to state functions or the international order.17

Another approach to measuring peace is the Global Peace Index (GPI). Unlike the HIIK, the GPI does not count the number of conflicts,17 but rather ranks states according to their level of peacefulness. The GPI is based on 23 qualitative and quantitative indicators and examines areas such as the level of social security, the extent of ongoing internal and international conflicts, and the degree of militarization.28

Crisis and conflict regions can be assessed on the basis of the results of these two approaches. For companies operating in these regions, it is advisable to use frameworks that enable them to specifically identify and prioritize their efforts. On the one hand, this can create entrepreneurial added value and improve competitiveness, while on the other, it promotes positive social and environmental impacts.29

One of these frameworks are the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) mentioned above. These were adopted in 2015 in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.27 These goals are increasingly referred to worldwide as “The Global Goals” and are used by a large number of stakeholders and various private sector organizations.30 The agenda comprises 17 goals for sustainable development and acts as a guideline for joint action at all levels of society.31

SDG 16 is formulated by the United Nations (2015) as follows: “Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels” (p. 28).27 This involves not only a normative agenda, but also the development of principles of action. The central functions and ethos of the institution are also defined.32

SDG 16 consists of 12 targets, which in turn are measured using corresponding indicators. These targets are formulated in very general terms and describe far-reaching demands, such as the reduction of all forms of violence and violence-related mortality rates (16.1), the promotion of the rule of law at national and international level (16.3) or the establishment of effective and transparent institutions at all levels (16.6) (for a list of all targets and indicators, see Annex A).34

A total of 23 indicators were formulated to measure these targets. These indicators are wide-ranging and cover various dimensions in line with the formulated targets, which are of crucial importance for achieving the goals.35 For example, the number of victims of homicide per 100,000 inhabitants is used as an indicator for the reduction of violence (16.1.1). Another indicator is the proportion of companies that have paid a bribe to a public official in the last 12 months (16.5.2) or the proportion of positions in public institutions compared to the national distribution (16.7.1).34

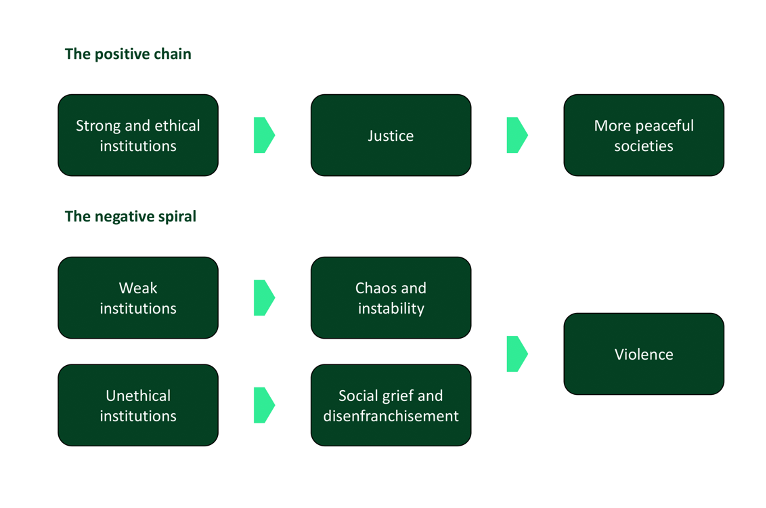

In contrast to many other SDGs, SDG 16 formulates a series of aspirations that can only be achieved indirectly. Strong and ethical institutions that aim to promote justice and thus ultimately contribute to peace can never be created directly through the influence of companies. It is important to understand that SDG 16 is not a concrete guideline for companies to follow. However, SDG 16 establishes a consensus that the issues of peace, justice and strong institutions are a real responsibility for all actors, including business. It also clarifies that the reduction of violence is based on broad institutional acceptance and support for fair and universal justice.33

2.2 Effects of peace

The influence of peace and justice in regions where companies operate is reciprocal.36 On the one hand, there are certainly a number of companies that benefit from doing business in regions of crisis and war.23 On the other hand, economic sectors such as tourism or retail generally benefit from stability and therefore from peace.23 Companies are generally dependent on stable and efficient institutional framework conditions, including functioning markets for goods and services and reliable regulatory mechanisms.37 This stability also reduces the political risk for companies that arises in connection with operations in crisis regions.38 It can be concluded that the establishment of sustainable peace is in the best interests of the economy and economic policy.39

Another argument in favor of the economic advantage of peace is the opening up of new markets that were inaccessible due to previous conflicts.39 There is also the risk that the property of companies in war zones can be confiscated or misappropriated by warring parties.40 Furthermore, the reputation of companies increases if they actively participate in the promotion of peace.41

3 Implementation

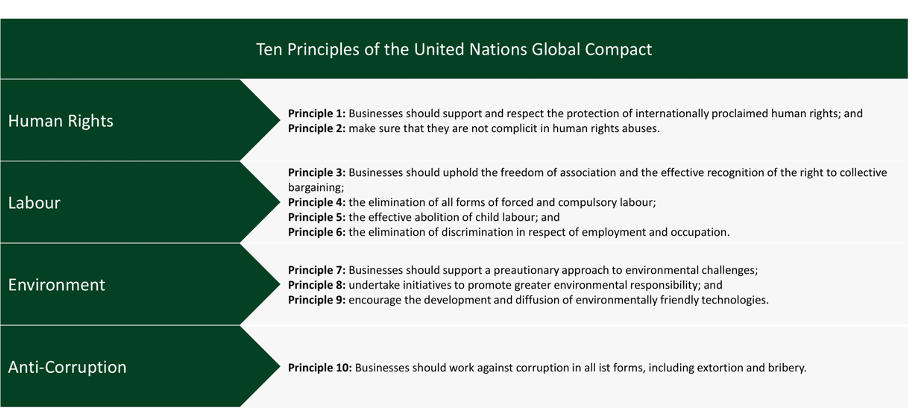

Since businesses, NGOs, the public sector, unions, academic and other institutions are the acting parties in societies they have an influence on the prevalent level of peace and justice. To support them at building and maintaining structures like supply chains in a responsible manor, that establishes peace and justice, the United Nations introduced the ‘UN Global Compact’ (UNGC) program in 1999. It is a voluntary initiative, meaning it is not legally binding and cannot be enforced by law nor can the UN punish misconduct.42 The core of it is a ten-point guideline, which is connected to the todays SDGs and its predecessor the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), aiming to achieve a more inclusive and sustainable economy that benefits all people, communities and markets. Besides the advises the program’s strength on the Global Compact is the networking aspect. Currently more than 25.350 members spread over 160 countries are participating in the program43, which offers rare networking opportunities. In 2013, the program was expanded to include the B4P initiative.24 In the following sections the UNGC will be presented.

3.1 Human Rights

The aforementioned ten principles are separated in four categories, starting with two principles concerning ‘Human Rights’ and are referring to the ‘Universal Declaration of Human Rights’. The first principle “Businesses should support and respect the protection of internationally proclaimed human rights”. The motivation for commitment lays in the different stakeholders’ reactions to missing compliance, consumers, partners and investors could lose interest while the firm may face legal problems, all resulting in worse performance. Businesses shall respect human rights in all their operations, especially in regions of weak governance. The UN points out three sets of factors to consider, firstly the careful selection of regions to operate in is one way of minimizing the risk of conflicts, secondly questioning of the own activities, and thirdly looking at all sort of partners and their actions. Furthermore, an official statement and the implementation of respective policies are suggested as well as monitoring and reporting on the companies’ actions. Firms can contribute to the topic by integration of human rights support in their own activities, by strategic social investments, public policy engagement and partnerships for collective actions. Examples for human right support are the provision of safe and healthy working conditions and the absence of discrimination, forced labour, and child labour.45 The second principle “Businesses should make sure that they are not complicit in human rights abuses” faces the three forms of complicity: direct, beneficial and silent complicity. The motivation to respect this principle remains the same as for the first, stakeholder reactions for the case of failures becoming public. Although the risk of being part of human rights abuses cannot be entirely erased it can be minimized by assessing the corporate environment, develop concrete policies and ensure their effectiveness, engage in the discussion towards stronger protection of human rights, and use the own power to move others to compliance.46

3.2 Labour

The following principles three to six stand under the topic of ‘Labour’ and are derived from the ‘International Labor Organization’s Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work’. The third principle “Businesses should uphold the freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining” should concern businesses because the dialogues between employers and workers become more efficient and solution oriented when parties unite and elect representatives for negotiations. The most important steps towards compliance are respect for the workers right to join trade unions and support employees that engage in the process of negotiating collective agreements. Also showing interest in the employees concerns and search for solutions will contribute to constructive collective bargaining.47

As a fourth principle the UN names that “Businesses should uphold the elimination of all forms of forced and compulsory labour”. This target is connected to the first one because forced labour restricts the freedom of individuals. Also, it reduces the chances of developing as a person and as a worker. In addition, it may have a negative influence on families and whole communities by reducing the potential incomes. Examples for actions in the workplace include clarification of the topic, inclusion into the firm’s policy, and ensuring not to use any form of forced labour within the own operations including partners. Outside of the narrow business context engagement in education on the topic and collaboration with other firms or local organizations to fight the issue are recommended steps.48

Also already mentioned in the human rights section is that “Businesses should uphold the effective abolition of child labour” which is also the standalone principle five, which is referring to International Labour Organization (ILO) conventions No. 138 and 182. Paying attention to the various categories of work and the referring legal age that allows light work to twelve-year olds in developing countries and regular work at the age of fourteen. In developed countries children must be one year older while in both cases hazardous work is not acceptable for children below 18. Child labour has drastic consequences on a child’s development, resulting in decreasing chances to become an independent and qualified worker in the adulthood. The public reaction to cases of child labour in the sphere of a firm will be a loss in image value and may affect the profitability of the company. For this reason, companies are expected to investigate if their supply chains contain any form of inappropriate child employment, if so, they must be removed but also cared for, by provision of education and a source of income for the family to erase the pressure laying on the child.49

“Businesses should uphold the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation” is the sixth principle. Compliance demands the absence of discrimination at all stages of employment, including recruitment, and suggests selecting employees based on performance and qualification. Higher qualification and a diverse team can have a positive influence on a firm’s performance, for this reason the adoption of a company policy to manifest these practices. Also treat complaints and the individual needs of workers with due respect.50

3.3 Environment

The environmental protection section roots in ‘the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development’. The seventh principle “Businesses should support a precautionary approach to environmental challenges” starts off the section concerning the environment. The precautionary approach is meant to save money as environmental remediation is expected to be more costly, also, environmentally sustainable investments are considered to have better long-term returns. To include the environmental protection into the company’s code of conduct and taking environmental concerns into account at strategic decisions in combination with stakeholder management are steps to fulfill this principle.51 In the eighth principle “Businesses should undertake initiatives to promote greater environmental responsibility” the mission to protect the environment, and simultaneously the public wellbeing, continues. Businesses have a natural interest in production efficiency which also leads to a better economic performance and can have an influence on the firm’s reputation. Companies need the desire to become sustainable and to adopt adequate targets to follow it in when making decisions and renewing for example a product. Tools that assist the management are environmental impact and risk assessments, life cycle assessment, and ways of communication and reporting to stakeholders in a transparent way.52

“Businesses should encourage the development and diffusion of environmentally friendly technologies” subsequently is the ninth principle, as the previous two already suggested the use of progressive technologies. Increased efficiency and reduced externalities are the expected benefits of investments in innovative technologies, referring to individual units and processes but also the implementation into an industry-wide frame. The targeted change can take place in every instance, from product design over inputs, material and energy use and production processes. The approaches from a strategic side include internal policies, the aid of Research and Development to create new opportunities.53

3.4 Corruption

The tenth principle “Businesses should work against corruption in all its forms, including extortion and bribery” was added in 2004 as a supplement to the existing frame. It faces the issue of corruption based on the ‘United Nations Convention Against Corruption’ while demanding that businesses work against corruption in all its forms, including extortion and bribery. The problems caused by the issue range from the legal consequences and reputation losses to financial costs. For executives, the inclusion of anti-corruption regulations into corporate policies and the report on practices and progress are steps to undertake. Furthermore, firms can become part of collective actions and unite against the topic with other companies and organizations.54

3.5 Critique

Critique on the UNGC mostly faces the lack of control mechanisms and monitoring. This would lead to avoidance of real progress and promotion of a minimal effort policy which is possible also due to the requirements explained in the following.55 The Process starts with a short official ‘Letter of Commitment’ to be filed by a firm’s CEO where the ten principles must be agreed, also express support towards the SDGs, and to submit an annual report. The yearly report named ‘Communication on Progress’ mandatorily includes a statement by the CEO expressing continued engagement, a description on progress, and a measurement of outcome. However, this report will not be revised by the UN itself, rather than allowing this to the public or to activists, who can report bad performances through a complaint system.55 Failing submission once leads to a change in status, becoming a ‘non-communicating’ member, while a consecutive second failure results in the label ‘inactive’. A third year without reporting will result in delisting.42 Committing to the UNGC is very attractive to companies, because of the UN’s high reputation and international status. A study by Orzes et al. (2015)shows how, based on an empirical analysis of 810 publicly traded US-firms, members of the UNGC perform better in terms of sales growth and profitability.56 Benefits gained solely by membership are in contrast to the low requirements, these circumstances may tempt members to avoid real progress on CSR-issues while displaying themselves as part of an ambitious movement. This phenomenon is called ‘bluewashing’ similar to the topic of greenwashing but referencing to the blue-themed UN. Besides missing participation even on the low level requirements, clear acts against the ten principles will not automatically lead to an exclusion showing the weak nature of the UNGC.57

The GC is a global public policy by the UN that is not mandatory to any organization. It was not founded to be the one guiding framework and to control companies in their actions but to help interested organizations to improve their sustainability performance by presenting a desired condition in the fulfillment of the ten principles. For those who are motivated to engage in sustainable topics and seek advice, guidance, and a network a membership in the UNGC can have a rewarding outcome also in a business performance perspective. The program is easy to enter and does not demand priority in the first place, which allows a development inside a company without putting too much pressure on it.58

3.6 Ukraine as example

An example of a crisis shook nation involved in armed conflict is the Ukraine who deals with losses of infrastructure due to destruction and losses of workforce, because of people becoming soldiers, leave the country or in worst case become victims of the war. The Russian aggressor on the opposing can be clearly recognized as it is an international conflict with governments as decisionmakers. What allows managers to avoid cooperations that benefit a party committing crimes and provoking injustice as described below.

From an economic point of view the damage can be estimated north of $486 billion but the country and its economy are still vital and growing after the crash in 2022. About 19,000 businesses have relocated from the east to the safer west of the country, similarly, announced foreign investments also target the western regions. Over the time of the invasion until end of 2023 sales in the east sunk by 70 percent compared to 39 percent in western regions.59 Excluding the eastern zones where the war takes place, life in the central and western regions normalized in a way since the start of the invasion. Services are available and people attend public places.60 In contrast many are in mourning because of the losses, especially in their communities and families. While the draft age was already lowered to 25 to meet the need of soldiers, bribery rises with the attempt to buy oneself out of the draft.61

4 Drivers and Barriers

To look at the drivers and obstacles regarding peace and justice, it is suitable to address the role of businesses in a certain region and how their actions affect peace and justice. In this way different types of decisions made by these businesses should be categorized in either drivers or barriers regarding either encouraging peace and justice or prevent such.

In that case we decided to have a look at case studies, in which companies play a role in the peace policy state of a state or region, how they affect the development with their actions and how economy policies in general influence the creation of sustainable peace and justice rather than differentiating between drivers and barriers. In this way we evaluate the do’s and don’ts of company actions and economic policy processes.

4.1 The Role of Multinational Companies

A negative example is the role oil multinational corporations spearheaded by Shell played in the destabilization of the region around the Niger Delta.

The Niger Delta accounts 90 percent of the total national exports and 70 percent of the national revenue mainly coming from the export of oil and gas. Therefore, the region is highly dependent on the revenues resulting from their exports. Despite being one of the main sources of the national exports, the area around the Niger Delta has a high poverty level in comparison to the nations average. About 70 percent of the community lacks access to clean water, has no passable roads or electricity supply, a shortage of medical facilities, a large number of dilapidated schools and suffers from severe environmental degradation due to oil production.62

A history of violent activities by both the Nigerian state and the MNCs with ruthless exploitations of natural resources resulted in coordinated local resistance after 1999, which was expressed with the rise of ethnic militia claiming to represent the interests of the local communities in their struggle for social justice. One of the most popular militia groups, the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) threatened to cut the Nigerian oil output by 30 percent and even made genuine effort by sabotaging oil production to the point, that in 2007, about 700.000 barrels of oil a day were shut down due to political instability and insurgent attacks.63 These losses resulted in a 23,7 billion USD decrease in Nigerian state revenues directed linked to MEND attacks.

As an approach against the growing political and economic instability, the Nigerian state announced an amnesty in June 2009, which included free surrender for ex militants in a time period of 60 days, no prosecution for their crimes and a commitment for a reintegration and rehabilitation program. That indicated a direct link between the actions of companies in a certain region and the state of federal peace.

Following the conflict getting out of hand, both the MNCs and the Nigerian government made approaches to tone down the riots by offering a demilitarization and reintegration program for militants. But the militants quickly concluded that the main objective of these initiatives was to ensure the export of oil without any complications rather than a sustainable reintegration process.64

Due to the ongoing robberies and manipulations of the oil exports civil organizations acquired a growing role in the conflict: They forged strategic partnerships with local communities to evaluate the feedback from the communities for the actions made by the conflict parties to properly represent them when participating in the peacemaking process.65

4.2 Role of companies in peace building

To further describe the role of companies in conflict regions and thus a possible development towards a peaceful situation, it is necessary to differentiate between the points in time of a conflict situation: The role of companies can differ depending on whether in the country or region peaceful conditions are to be established.

In the middle of a conflict, companies can take on the role of a mediator between the conflict parties. An example of the role of a mediator in a national conflict is the ongoing social and political unrest in Colombia.

In Colombia, the Ideas for Peace Foundation (FIP) was founded in 1999 by several large local companies. The purpose of founding this think tank was to provide advisory support to the government and to develop an agenda for negotiations between the parties. In addition, the FIP has invested in research in the areas of peacebuilding, development and security.66

But companies can also play an important role in peacebuilding outside of negotiations: By supporting peace negotiations, companies provide a foundation by paying taxes, providing jobs or making other contributions to help the government with institutional reforms, disarmament and support for victims of the conflict.66

In the case of Colombia, members of business associations occupied important positions in the government’s negotiating team during the peace negotiations.66 This went so far that business associations regularly met at the government headquarters to discuss the government’s negotiating strategies.66,67

In conflict situations, unemployment can be an accelerating factor: In the case of Colombia, unemployed young people play a decisive role in both crime in urban areas and in armed conflict.66 Conversely, it is believed that a sustained ceasefire could create up to 800,000 jobs a year, which could contribute to Colombia’s economic growth of up to 1.5 percent per year.66

It is believed that the presence of high-ranking company representatives creates legitimacy for the negotiations and their results and secures resources to implement the results of peace negotiations sustainably. To achieve long-term economic growth, investments at the international level are also necessary in the long term. Both national companies and the government are responsible for ensuring appropriate security for these investments and for further developing institutional facilities. In addition, there is the expansion of infrastructure and capacities. In addition, it is believed that increasing participation of national companies in international free trade agreements or growing business activity by international companies in Colombia can lead to a spillover effect as a supporting factor for peace negotiations: It is expected that standards in corporate social responsibility will be established more often by national companies or that international norms will be adapted in business practice.66

Companies in Colombia concluded that ongoing conflicts represent a decisive disadvantage in the long term, especially in international competition, which is why they have decided to actively participate in the peace process themselves.66

That the methods of peacebuilding show immediate effect, can be reflected in the development of the homicide rate, which fell from 80 homicides per 100,000 population in 1991 to 32 per 100,000 in 2012. These positive tendencies allowed Colombia to become one of the most promising middle-income countries for investment in the last years.68

Despite the ongoing civil issues in Colombia, the country has become one of the best practice examples in peacebuilding with the inclusion of economic players. On the one hand their representatives took on a role as advisor for the government to forge a peacebuilding and install an institution with the FIP that navigates and distributes resources that are explicitly needed in different areas to build a foundation of sustainable peace and justice. On the other hand, they acted as mediators between the conflict parties helping to negotiate terms for an agreement on ceasefire. It can be stated that companies might not initiate ending a conflict in the first place but are very capable of positively affecting peace building processes as a mediator and an advisor.

4.3 Development of Sustainable Peace and Justice

After we had a look at how companies in particular play a role in either encouraging or hindering the develop of peace and justice in a conflict region, it also makes sense to analyze how economy policies, and the different approach influence the establishment of peace programs.

Having already concluded that poverty causes countries to develop a higher potential for conflict and that conflicts prevent a country from recovering from poverty and fighting it,69 the question shall be asked as to which methods should be implemented to counteract poverty as effectively as possible and to create lasting peace and justice.

The obvious solution might be to generate economic growth, which then counteracts poverty and minimizes the potential for conflict. In the past, attempts were made to establish neoliberal approaches in crisis regions to create maximum growth incentives in the economy. The result of these efforts was that, due to the lack of control mechanisms and the lack of support for peace programs, infrastructure projects and projects that were primarily intended to benefit the vast majority of the population, conflicts flared up again in many countries especially in South America and left them in a worse state than before the original conflicts were resolved.69 Unequal treatment between the majority of the population and a benefiting majority became one of the key reasons for unsustainable peace and recurring grievances.70

This phenomenon could be observed in countries in South America as well as in the conflict in the Niger Delta mentioned above, where local resistance groups demanded a fairer distribution of profits from oil production. From this it can be deduced that the goal should not simply be to achieve economic growth, but to distribute the wealth that can be gained from it fairly to specifically counteract grievances and combat inequalities.69

Otherwise, unevenly distributed profits from economic growth can lead to tensions between population groups. The implementation of neoliberal economic reforms increases the likelihood that socioeconomic grievances will not be reversed, but rather economic growth will be generated that will further increase these inequalities.69

This is a problem especially for crisis-ridden countries, as there are already high levels of socioeconomic tension there, which means there is a great risk of falling into another crisis. In addition, these countries are hardly able to regulate the economic growth generated by the reforms, as they lack the structures to do so. The missing structures include not only those at the institutional level that are responsible for regulating market policy reforms, but also those that curb the increasing risk of corruption and rampant privatization caused by future economic growth.69

If the reforms reignite conflicts, the countries are usually unable to contain them because they lack the means and structures for peaceful dispute resolution, and the tense conditions in society also make a peaceful solution difficult.69

A good example of how a crisis-ridden country develops when only economic growth is considered to achieve sustainable peace, while programs that specifically promote peace and justice are neglected, is El Salvador. When a ceasefire agreement with comprehensive regulations was reached in El Salvador after a temporary settlement of the civil war, the National Reconstruction Program was introduced, under whose leadership various programs to secure peace were to be started.69

Instead of promoting these programs economically, the focus of the subsequent economic reforms was exclusively on generating economic growth and implementing reforms with neoliberal approaches.69

As a result, peace programs clearly failed to achieve their goals due to a lack of financial resources, in particular financial resources for projects such as judicial reform, the introduction of an office to monitor human rights and the introduction of a national federal police force were too low to be successfully implemented.71 In addition, only 50% of the funds required for the transfer of land ownership were made available.69

The overall result was that the poorer part of the population, especially in the urban part of the country, were significantly disadvantaged by the reforms.69

The main reasons for the renewed civil unrest and the rise in crime were the high unemployment and the lack of integration of former civilian fighters after the conflict was resolved.72 The increase was so great that in the mid-1990s the number of victims was higher than after the end of the civil war.70

Looking back, in the first six years after the introduction of the economic reforms, El Salvador’s Human Development Index fell by over ten percent.70 The reforms did indeed achieve the planned economic growth, and between 1992 and 1997 real GDP increased by up to six percent,73 although it is assumed that this growth mainly benefited a small, wealthy minority in El Salvador, especially owners of large areas of land who had previously represented El Salvador’s financial aristocracy.70

It can therefore be stated that sustainable peace cannot be created through economic growth alone, because economic growth should be viewed in a differentiated manner in this case. Unequal distribution of wealth has the potential to fuel social grievances and reignite crises. What is also problematic in this case is that countries in this situation do not have the institutional structures to resolve the conflicts that arise in a peaceful manner, precisely because of previous crises.

References

1 Geneva Academy of International Law and Human Rights. Today’s Armed Conflicts. (2024).

2 UNHCR. UNHCR’s Refugee Population Statistics Database. (2024). <https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/>.

3 Corp, R. & Herrmannsen, K. Children’s hospital hit as Russian strikes kill dozens in Ukraine. (08.07.2024). <https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cl4y1pjk2dzo>.

4 Kelly, A. & Joya, Z. ‘Frightening’ Taliban law bans women from speaking in public. (26.08.2024). <https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/article/2024/aug/26/taliban-bar-on-afghan-women-speaking-in-public-un-afghanistan>.

5 Spring, J. Tropical forest loss eased in 2023 but threats remain, analysis shows. (04.04.2024). <https://www.reuters.com/world/tropical-forest-loss-eased-2023-threats-remain-analysis-shows-2024-04-04/#:~:text=Deforestation%20globally%20rose%203.2%25%20in,and%20is%20harder%20to%20measure.>.

6 Fernández, S., Arce, G., García-Alaminos, Á., Cazcarro, I. & Arto, I. Climate change as a veiled driver of migration in Bangladesh and Ghana. Science of the total environment 922, 171210 (2024).

7 Galtung, J. Violence, Peace, and Peace Research. Journal of Peace Research 6, 167-191 (1969).

8 Werkner, I.-J. in Handbuch Friedensethik (eds Ines-Jacqueline Werkner & Klaus Ebeling) 19-32 (Springer VS, 2017).

9 Bonacker, T. & Imbusch, P. in Friedens- und Konfliktforschung: Eine Einführung Vol. 4 (eds Peter Imbusch & Ralf Zoll) (VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2006).

10 Hansen, T. Holistic peace. Peace Review 28, 212-219 (2016).

11 Sönsken, S., Kruck, A. & El-Nahel, Z. in Berghof Glossary on Conflict Transformation and Peacebuilding: 20 essays on theory and practice (ed Berghof Foundation) 35-41 (Berghof Foundation, 2019).

12 Hamedi, A. The concept of justice in Greek philosophy (Plato and Aristotle). Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5, 1163-1167 (2014).

13 Kennedy, R. G. The Practice of Just Compensation. Journal of Religion and Buiness Ethics 1 (2010).

14 Wu, L. & Chiu, M.-L. Examining supply chain collaboration with determinants and performance impact: Social capital, justice, and technology use perspectives. international Journal of information Management 39, 5-19 (2018).

15 Alghababsheh, M., Gallear, D. & Saikouk, T. Justice in supply chain relationships: A comprehensive review and future research directions. European Management Review 20, 367-397 (2023).

16 Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Porter, C. O. & Ng, K. Y. Justice at the millennium: a meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of applied psychology 86, 425 (2001).

17 Berning, H. et al. Conflict Barometer 2022. (Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research (HIIK), 2023).

18 Baumann-Pauly, D., Nolan, J., Van Heerden, A. & Samway, M. Industry-specific multi-stakeholder initiatives that govern corporate human rights standards: Legitimacy assessments of the Fair Labor Association and the Global Network Initiative. Journal of Business Ethics 143, 771-787 (2017).

19 Scherer, A. G. & Palazzo, G. Toward a political conception of corporate responsibility: Business and society seen from a Habermasian perspective. Academy of management review 32, 1096-1120 (2007).

20 Hönke, J. Business for peace? The ambiguous role of ‘ethical’mining companies. Peacebuilding 2, 172-187 (2014).

21 Avant, D. & Haufler, V. Transnational organisations and security. Global Crime 13, 254-275 (2012).

22 Boele, R., Fabig, H. & Wheeler, D. Shell, Nigeria and the Ogoni. A study in unsustainable development: I. The story of Shell, Nigeria and the Ogoni people–environment, economy, relationships: conflict and prospects for resolution 1. Sustainable development 9, 74-86 (2001).

23 Oetzel, J., Westermann-Behaylo, M., Koerber, C., Fort, T. L. & Rivera, J. Business and peace: Sketching the terrain. Journal of business ethics 89, 351-373 (2009).

24 United Nations Global Compact (UNGC). Business for Peace. (United Nations, New York, 2013).

25 Miklian, J., Schouten, P. & Ganson, B. From boardrooms to battlefields: 5 new ways that businesses claim to build peace. Harvard International Review 37, 1-4 (2016).

26 Miklian, J. & Schouten, P. Broadening ‘business’, widening ‘peace’: a new research agenda on business and peace-building. Conflict, Security & Development 19, 1-13 (2019).

27 United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. (New York, 2015).

28 Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP). Global Peace Index 2024. (Sydney, 2024).

29 Dyllick, T. & Muff, K. Clarifying the Meaning of Sustainable Business: Introducing a Typology From Business-as-Usual to True Business Sustainability. Organization & Environment 29, 156-174 (2016).

30 Bebbington, J. & Unerman, J. Achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: an enabling role for accounting research. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 31, 2-24 (2018).

31 Hajer, M. et al. Beyond cockpit-ism: Four insights to enhance the transformative potential of the sustainable development goals. Sustainability 7, 1651-1660 (2015).

32 Whaites, A. Achieving the impossible: Can we be SDG 16 believers. GovNet Background Paper 2, 1-14 (2016).

33 Sustainable Development Goals Fund. Business and SDG 16: Contributing to peaceful, just and inclusive societies. (2017).

34 Economic and Social Council. Report of the Inter-Agency and Expert Group on Sustainable Development Goal Indicators (E/CN.3/2016/2/Rev.1). (United Nations, New York, 2016).

35 United Nations Development Programme. Monitoring to implement peaceful, just and inclusive societies: pilot initiative on national-level monitoring of SDG 16. (Oslo, 2017).

36 Fort, T. L. & Schipani, C. A. The role of business in fostering peaceful societies. (Cambridge University Press, 2004).

37 Khanna, T. & Palepu, K. Why focused strategies may be wrong for emerging markets. Harvard business review75, 41-51 (1997).

38 Oetzel, J., Getz, K. A. & Ladek, S. The role of multinational enterprises in responding to violent conflict: A conceptual model and framework for research. Am. Bus. LJ 44, 331 (2007).

39 Nelson, J. The Business of Peace: The private sector as a partner in conflict prevention and resolution. (The Prince of Wales Business Leaders Forum, 2000).

40 Tripathi, S. International regulation of multinational corporations. Oxford Development Studies 33, 117-131 (2005).

41 Aguilera, R. V., Rupp, D. E., Williams, C. A. & Ganapathi, J. Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Academy of management review 32, 836-863 (2007).

42 Carby-Hall, J. Multinationals, SMEs and non-profit organisations participating in the UN Global Compact. Lex Social: Revista de Derechos Sociales 10, 130-173 (2020).

43 UNGC. Homepage UN Global Compact, <https://unglobalcompact.org/> (n.d.).

44 Command Prompt Inc. UN Global Compact Commitment, <https://commandprompt.com/un-global-compact-commitment/> (n.d.).

45 UNGC. Principle One: Human Rights, <https://unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/mission/principles/principle-1> (n.d.).

46 UNGC. Principle Two: Human Rights, <https://unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/mission/principles/principle-2> (n.d.).

47 UNGC. Principle Three: Labour, <https://unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/mission/principles/principle-3> (n.d.).

48 UNGC. Principle Four: Labour, <https://unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/mission/principles/principle-4> (n.d.).

49 UNGC. Principle Five: Labour, <https://unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/mission/principles/principle-5> (n.d.).

50 UNGC. Principle 6: Labour, <https://unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/mission/principles/principle-6> (n.d.).

51 UNGC. Principle Seven: Environment, <https://unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/mission/principles/principle-7> (n.d.).

52 UNGC. Principle Eight: Environment, <https://unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/mission/principles/principle-8> (n.d.).

53 UNGC. Principle Nine: Environment, <https://unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/mission/principles/principle-9> (n.d.).

54 UNGC. Principle Ten: Anti-Corruption, <https://unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/mission/principles/principle-10> (n.d.).

55 Berliner, D. & Prakash, A. “Bluewashing” the Firm? Voluntary Regulations, Program Design, and Member Compliance with the U nited N ations G lobal C ompact. Policy Studies Journal 43, 115-138 (2015).

56 Orzes, G. et al. The impact of the United Nations global compact on firm performance: A longitudinal analysis. International Journal of Production Economics 227, 107664 (2020).

57 Christensen, A.-S., Hadick, E., Steglich, E. & Leddig, S. Limitations of the United Nations Global Compact: Bluewashing as a Structural Error. (n.d.).

58 John, M. in Corporate Social Responsibility – Mythen und Maßnahmen (ed Gisela Burckhardt) 85-87 (Springer Gabler, 2013).

59 Harmash, O. War upends Ukraine’s economy in a shift that may be permanent. (09.03.2024). <https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/war-upends-ukraines-economy-shift-that-may-be-permanent-2024-05-09/>.

60 Åslund, A. Ukraine’s wartime economy is performing surprisingly well. (02.01.2024). <https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/ukraines-wartime-economy-is-performing-surprisingly-well/>.

61 Yermak, N. In Western Ukraine, a Community Wrestles With Patriotism or Survival. (26.04.2024). <https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/26/world/europe/russia-ukraine-war.html>.

62 Zandvliet, L. & Pedro, I. Oil company policies in the Niger Delta. Cambridge, MA, Collaborative for Development Action (2002).

63 Watts, M. Petro-insurgency or criminal syndicate? Conflict & violence in the Niger Delta. Review of African political economy 34, 637-660 (2007).

64 Maiangwa, B. & Agbiboa, D. E. Oil Multinational Corporations, Environmental Irresponsibility and Turbulent Peace in the Niger Delta. Africa Spectrum 48, 71-83 (2013).

65 Obi, C. I. in Intervention and Transnationalism in Africa: Global-Local Networks of Power (eds Thomas Callaghy, Ronald Kassimir, & Robert Latham) (Cambridge University Press, 2009).

66 Rettberg, A. Peace is better business, and business makes better peace: The role of the private sector in Colombian peace processes. (2013).

67 Leal, F. & Zamosc, L. Al filo del caos: crisis política en la Colombia de los años 80. (Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 1991).

68 Financial Times. The New Colombia: Peace and Prosperity in Sight: the Country Comes of Age. (Penguin UK, 2013).

69 Ahearne, J. Neoliberal economic policies and post-conflict peace-building: a help or hindrance to durable peace? Polis journal 2, 1-44 (2009).

70 Paris, R. At War’s End: Building Peace after Civil Conflict. (Cambridge University Press, 2004).